Pickelhelm

Introduced into Prussia in October 1842 by decree of Wilhelm IV for the Prussian infantry, and quickly spread among other German states. The pickelhelm was made from reinforced leather, treated to a glossy black sheen, and enhanced with metal trim (silvered or gilded on officer pickelhelms), which included a metal spike at the pommel. Some helmets worn by artillery had a spherical decoration instead of a spike. Pickelhel stopped being used in 1918 due to the fall of the German Empire.

Helmet "Gaede" (Gaede-Helm, Stahlkappe M1915)

In 1915, the commander of the army group, General Gaed, concerned about the large number of soldiers receiving head wounds, himself designed and manufactured about 1,500 steel helmets, which were issued to soldiers on his sector of the front. After the appearance of the M1916 helmet, most of Gaed's helmets were melted down.

M16 steel helmet

The M16 helmet was developed in September 1915 by Friedrich Schwerd, and already in December it underwent combat tests on the Western Front. The M16 performed well in combat conditions and at the beginning of 1916 the steel helmet went into mass production. Steel helmets were produced in different sizes, from the smallest 60 to 70.

Initial sketches of the M16 helmet

Characteristic “horns” protruded from the sides of the helmet, onto which the Stirnpanzer armor plate was attached. The plate was put on the protruding horns and tightened at the back with a leather belt.

Helmet-mounted armor plate

Hard hats and helmets

A military helmet or helmet is a headgear to protect a soldier’s head from impacts, shrapnel and bullets with low penetrating force. Historically, the helmet was a stage in the development of the protective helmet, and received its name from the Latin word for a metal helmet. The helmet itself appeared with the formation of the first regular military units, i.e. still in the primitive world. At that time, protective headdresses were made from wood, birch bark, woven rods, leather, and animal skins. After the art of metal processing in ancient civilizations reached a sufficient level, they were able to make metal helmets. The oldest helmets, made of copper and gold, were found in the royal tombs of Ur and date back to the 3rd millennium BC. e.. Iron helmets first appeared in the 8th-7th centuries BC. e. in Urartu and Assyria and had a spheroconic shell-like shape. However, iron helmets in different regions were able to gain dominance over bronze ones only in the 1st millennium AD.

Mycenaean helmet made of boar tusks. Archaeological Museum of Heraklion.

Helmet of Ancient Greece, Corinthian type. Around 500 BC e. Museum in Munich.

Bronze helmet of the state of Urartu, VIII century. BC e.

The ancient Greek hoplite's helmet, along with the tunic and four chariot horses, became a symbol of the Hellenic era, from the legendary Trojan War to the Roman conquest. They were replaced by Roman helmets, which were used almost until the Middle Ages.

Replica of the helmet of a Roman centurion of the 2nd century. n. e.

Early helmets of medieval Europe were formed under Eastern influence. Initially, these were frame helmets, riveted from several segments on a frame. From the 10th century, the spread of Norman helmets began, which no longer had a frame structure, but were directly riveted or soldered from several segments. These helmets were often equipped with a nosepiece. In the 12th century, helmets with a cylindrical crown appeared, which were later transformed into topfhelms - pot-shaped helmets, which were preserved until the 14th century.

Replica of an Anglo-Saxon Wendel-type helmet from the Sutton Hoo burial in England, 7th century.

Russian shelom of the 16th century.

At the beginning of the 14th century, bascinets appeared in Europe, covering the back of the head but leaving the face open. They were often equipped with visors. In the 15th century, armet and salade appeared, as well as barbut. In the 16th century, simple infantry helmets appeared - cabassets, and, later, morions. In the same century, burgonet appeared, as well as light iron caps and tiles. In the 17th century, under Eastern influence, through Poland and Hungary, shishakas or erichonkas with a visor, ears and a back cover became widespread in Europe. In the second half of the 17th century, helmets, along with armor, almost completely fell out of use.

Italian bascinet.

Spanish morion.

Cabasset of a French infantryman.

Big shot of Tsar Mikhail Romanov.

After the advent of firearms, armor gradually disappeared, and in the 18th century soldiers fought without helmets. Metal helmets are still used in heavy cavalry, but by the beginning of the 20th century they served more for ceremonial purposes than for head protection. In the Napoleonic wars, the main losses were caused by artillery fire. Helmets did not protect soldiers from buckshot and cannonballs; maneuver on the battlefield was much more important. When retreating from Moscow, the French cuirassiers first abandoned their armor as soon as they were forced to walk on foot due to the death of their horses.

After the outbreak of World War I, steel helmets (helmets) were reintroduced in the armies of European states, the main purpose of which was to protect the soldiers’ heads from shrapnel, artillery shell fragments and non-ballistic strikes. In 1915-1916, three main types of helmets were adopted in all major countries participating in the war.

— “Horned” — Stahlhelm M16 with a developed neck, which became one of the symbols of the German army. There were ventilation holes on the sides, which were closed by cylindrical valves resembling short horns;

— French helmet of Adrian with a crest;

- Brodie helmet of the English army, nicknamed the "plate".

Stahlhelm - German M1916 helmet.

Hadrian's helmet M1916.

Brody's helmet.

During the interwar period, steel helmets and liners were improved, but they did not bring fundamental changes to their design. Some countries continued to fight with helmets left over from the First World War. At the same time, new types of helmets appeared, made practically without the use of steel: parachutists, tank crews, motorcyclists, pilots. Military helmets of poorer quality began to be used in air defense, as well as in various paramilitary organizations: police, firefighters, aerial observers, etc.

Images and descriptions of the most common helmets used during World War II by some countries are given below:

Bulgaria Great Britain Germany Greece Denmark Spain Italy Canada Netherlands Poland USSR USA France Czechoslovakia Switzerland Sweden Japan

Share in:

Stahlhelm 1918

The main distinguishing feature is the refusal to attach the chin strap directly to the helmet and, accordingly, there is no need for a part riveted to the helmet sphere. The design of the balaclava also changed: “D” rings began to be used to fasten the chin strap (by analogy with the Austrian version), which began to be riveted to the base rim. The chin strap has also changed: the sliding buckle has been replaced by a frame clasp with a “tongue”, and holes have appeared in the strap for the “tongue” of the buckle. In general, this design turned out to be more technologically advanced in production and stronger in operation, and, importantly, provided better fixation of the helmet on the soldier’s head.

Back to basics?

So, it turns out that a hundred years of development were wasted? Is it time to throw out the newfangled Kevlar and order the good old Adrians from factories? Let's figure it out.

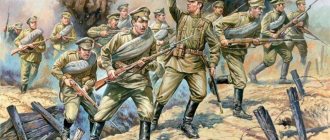

Red Army soldiers in Adrian helmets

On the same topic

Frightening realism: trench life of the First World War in color

First of all, let's pay attention to what tests the helmets were subjected to. They were tested only for protection from a shock wave, and coming strictly from above. In what situation does such a defeat of a soldier occur? Obviously, when he is sitting in an open top cover (for example, in a trench), and an artillery shell explodes above him. Actually, it was for this situation that helmets were invented in the First World War.

The most terrible weapon then, contrary to popular belief, was not a machine gun, but a cannon. To hide from artillery fire, the army dug into trenches. But the trench did not protect completely - by accurately calculating the timing of the fuse, it was possible to ensure that the shell would detonate exactly above the trench, raining down fragments and a shock wave on the most vulnerable place of those sitting in it - that is, on their heads. Which at the beginning of the war were covered only with cloth caps or, at best (for the Germans), leather “Pickelhaube”.

British "Tommies" in Brodie helmets

It is not surprising that the old helmets did an excellent job of the task for which they were designed. They even have a specific shape - remember the most famous helmet of the First World War, the British “saucer”, created by John Leopold Brodie. Its wide brim is designed just to act as an umbrella, covering as much of the owner’s body as possible from nasty things flying from above.