On December 25, 1979, Soviet troops entered Afghanistan, and two days later, special forces of the USSR KGB stormed the palace of the country's president, Hafizullah Amin. So 40 years ago, the protracted Afghan war began, from which the USSR emerged seemingly undefeated, but definitely not a winner. The Soviet army was not ready to fight the partisans, who were also supported by the West, and did not help its supporters stay in power. Lenta.ru recalls how the last war of the Soviet Union began, continued and ended.

Hill fortress

Now the Taj Beg Palace on the outskirts of Kabul is just an impressive ruin. But once upon a time, the huge residence, decorated by German craftsmen, was a real fortress. In 1979, the head of civil war-torn Afghanistan, Hafizullah Amin, was well aware that his security was under threat, because by that time his repression had even affected the socialist army officers with whose help he came to power. By that time, Amin had already survived at least two assassination attempts.

Therefore, all the roads to the palace, except one, were mined, and the only way to it led through several security lines. Behind the building, three tanks were buried in the ground, heavy machine guns stood along the perimeter, and an anti-aircraft regiment with 12 guns protected the head of state from air strikes. The palace was surrounded by barracks and headquarters - in total, more than two thousand soldiers served in its garrison, and two tank brigades were stationed nearby, just in case.

All this did not help the dictator to save himself when Operation Storm 333 began in Kabul on the evening of December 27. A significant role in its success was played by the fighters of the so-called Muslim battalion of the GRU - Soviet Tajiks, Uzbeks and Turkmens, who guarded the palace in agreement with the USSR.

With their help, special forces from the KGB units “Zenit” (later it would become widely known as “Vympel”) and “Thunder” got as close to the palace as possible, whose task was to physically eliminate Amin.

The fighters were dressed in Afghan uniform, and those of them who belonged to the “musbat” did not even outwardly stand out from the environment, but at some point the defenders of the residence still realized that something was wrong and opened fire on the Soviet soldiers heavy fire. The assault began from several directions at once: the special forces were helped by a company of paratroopers, who had anti-aircraft Shilkas and grenade launchers at their disposal. It was their snipers who took down four sentries in time - the first to die during the assault.

Ruins of the royal palace that served as the residence of Hafizullah Aminu

Photo: Alexander Zemlyanichenko / AP

Almost simultaneously with the start of the operation - it was announced by two red flares - Soviet saboteurs blew up the well in which the palace communications center was located. So Amin was cut off from the military loyal to him. Many tankers and motorized riflemen of the DRA army simply did not have time to get to their combat vehicles due to grenade launcher fire. And those who got there discovered that there were no bolts in the machine guns and guns - this was the work of the USSR military advisers. The KGB officers stationed in the palace left their housing before the battle under a plausible pretext - of course, having sketched and provided their colleagues with plans of its premises.

Although about 1.7 thousand Afghan soldiers surrendered during the assault, the rest put up serious resistance: the last of them fought until the morning - and there were still three times more of them than the attackers. “We walked up a narrow stone staircase. The shelling was so strong that it resembled pouring rain,” recalls Rustamkhoja Tursunkulov, a retired KGB colonel who commanded one of the Musbat combat groups in 1979.

Amin, recovering from a poisoning attempt organized by Soviet agents - he was saved from death by Soviet doctors who were unaware of the KGB's plans - heard the shooting and ordered his assistant to call Soviet military advisers and ask for help. When he learned that the Soviets were attacking, he threw an ashtray at the adjutant, shouting: “You’re lying, it can’t be!”

The operation is still considered one of the exemplary operations in world combat practice: 43 minutes passed from its start to Amin’s death. The paratroopers defeated the tank columns as they approached with the help of anti-tank guns, taking the personnel prisoner. On the Afghan side, according to various estimates, from 40 to more than 200 soldiers and officers were killed, as well as Hafizullah Amin himself and his son. The dictator's body was wrapped in a bloody carpet and buried not far from the palace, filling the grave with stones and leaving no mark.

The Soviet side lost at least 14 people killed. At least five Musbat soldiers died by accident - the paratroopers who arrived a little later mistook them for locals. They shot until one of the fighters from the southern republics approached their armored personnel carrier and reported that they were attacking their own. Also, during the clearing of the premises from the fire of the special forces, the same military doctor who had previously pumped Amin out died.

The next day, the people of Afghanistan learned: Amin, a “CIA agent”, executioner of Afghan civilians and enemy of the revolution, had been killed, the government had changed, and Soviet troops were on the territory of the country.

April 27, 1980. Soviet soldiers in the DRA, April 1980.

Photo: Vladimir Vyatkin / RIA Novosti

Storming of Amin's Palace

The deployment of troops began on December 25. Two days later, Amin, while in his palace, felt ill and lost consciousness. The same thing happened to some of his close associates. The reason for this was poisoning, which was organized by Soviet agents who worked as cooks at the residence. Amin was given medical assistance, but the guards sensed something was wrong.

At seven o'clock in the evening, not far from the palace, a Soviet sabotage group stalled in its car, which stopped near the hatch that led to the distribution center of all Kabul communications. The mine was safely lowered there, and a few minutes later there was an explosion. Kabul was left without electricity.

Thus began the Afghan War (1979-1989). Briefly assessing the situation, the commander of the operation, Colonel Boyarintsev, ordered the assault on Amin’s palace. The Afghan leader himself, having learned about the attack by unknown military personnel, demanded that his entourage ask for help from the Soviet Union (formally, the authorities of the two countries continued to remain friendly to each other). When Amin was informed that USSR special forces were at his gate, he did not believe it. It is not known exactly under what circumstances the head of the PDPA died. Most eyewitnesses later claimed that Amin committed suicide even before Soviet soldiers appeared in his apartment.

One way or another, the operation was successfully carried out. Not only the palace was captured, but the whole of Kabul. On the night of December 28, Karmal arrived in the capital and was declared head of state. The USSR forces lost 20 people (among them were paratroopers and special forces). The commander of the assault, Grigory Boyarintsev, also died. In 1980, he was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Good neighborly help

The USSR came to the full-scale deployment of troops after many years of peaceful interaction with Afghanistan. Partnership relations flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, when the country was ruled by Mohammed Zahir Shah. After the victory in World War II, the international position of the USSR strengthened, which also affected relations with the Afghan authorities. The Padishah visited the Soviet Union many times and hosted Soviet officials of the highest rank. As for many other countries, friendship with the communists was valuable for Afghanistan through comprehensive economic support - trade agreements, multimillion-dollar loans, construction of infrastructure practically from scratch.

By the end of the 1970s, factories built with the help of the USSR produced 60 percent of the country’s total industrial output, Soviet thermal power plants and hydroelectric power plants generated 60 percent of all electricity, 70 percent of the country’s roads—1,500 kilometers—were built by Soviet specialists. In total, from 1954 to 1978, the USSR spent about $1.3 billion on Afghanistan. Other countries also helped the Afghans, but Soviet aid accounted for more than half of all foreign investment.

Economic influence, as usual, was followed by political influence: every fifth Afghan student studying abroad studied in the Soviet Union, and thousands of military specialists were trained there. From the mid-1960s, a leftist opposition began to take shape; in 1965, the Marxist-Leninist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) was founded, which eventually came to power.

Losses

Many events of the Soviet years were subject to a one-sided communist assessment. Among them was the history of the Afghan war. Dry reports briefly appeared in newspapers, and television talked about the continued successes of internationalist soldiers. However, until the start of Perestroika and the announcement of the policy of glasnost, the USSR authorities tried to keep silent about the true scale of their irretrievable losses. Zinc coffins containing conscripts and privates returned to the Soviet Union semi-secretly. The soldiers were buried without publicity, and for a long time there was no mention of the place and cause of death on the monuments. A stable image of “cargo 200” appeared among the people.

Only in 1989, the newspaper Pravda published real data on losses - 13,835 people. By the end of the 20th century, this figure reached 15 thousand, since many military personnel died in their homeland for several years due to injuries and illnesses. These were the real consequences of the Afghan war. By briefly mentioning its losses, the Soviet government only further intensified the conflict with society. By the end of the 80s, the demand to withdraw troops from the neighboring country became one of the main slogans of Perestroika. Even earlier (under Brezhnev) dissidents advocated this. For example, in 1980, the famous academician Andrei Sakharov was sent into exile in Gorky for his criticism of the “solution to the Afghan issue.”

CPSU, PDPA and revolution

Afghan socialists initially supported the regime of President Mohammed Daoud when he staged a coup against Zahir Shah in 1973 and established a republic. But they quickly realized: his policy essentially differs little from the previous ruler, and besides, he gives preference not to the USSR, but to Western countries. The majority of opposition representatives were not happy with the Pashtun nationalism of the head of state either. The PDPA began planning to seize power, counting on the support of their neighbors to the north.

President Daud visiting New Delhi in August 1975

Photo: R. Satakopan/AP

Despite the ideological closeness of the Bolsheviks and the PDPA and the latter’s active contacts with the Soviet intelligence services, there is no direct evidence that the USSR participated in organizing the revolution in Afghanistan. On the contrary, the CPSU tried to warn its allies that in such an unstable situation a coup was dangerous - society was increasingly polarized, divided into Islamists and communists. But even if the Afghan socialists were not promised direct support, it was enough for them to know the foreign policy of the Soviet Union: revolutionaries in Angola, Ethiopia, Mozambique and other third world countries received from the Bolsheviks everything they needed to establish a socialist regime. In addition, they knew about the impending revolution in the USSR in advance, but the Afghan authorities did not receive this information.

Radical socialists wanted a change of power by force, moderates wanted a peaceful revolution. During the protests in 1978, all the main leaders of the movement were arrested, and there was no room for a peaceful path. Most of the ministers and military (many of whom studied in the USSR) supported the revolutionaries. Daoud's palace was stormed, the president, his family and associates were killed. The PDPA proclaimed a second, Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), removed Islamic elements from the country's coat of arms and added a red star. Three days after the revolution, the Soviet Union recognized the new government.

Chronology of the conflict

According to the nature of the fighting and strategic objectives, a brief history of the Afghan War (1979-1989) can be divided into four periods. In the winter of 1979-1980. Soviet troops entered the country. Military personnel were sent to garrisons and important infrastructure facilities.

The second period (1980-1985) was the most active. The fighting took place throughout the country. They were offensive in nature. The Mujahideen were destroyed and the army of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was improved.

The third period (1985-1987) is characterized by Soviet aviation and artillery operations. Activities using ground troops were carried out less and less, until they finally came to naught.

The fourth period (1987-1989) was the last. Soviet troops were preparing to withdraw. At the same time, the civil war in the country continued. The Islamists were never completely defeated. The withdrawal of troops was caused by the economic crisis in the USSR and a change in political course.

The thorny path to socialism

Having come to power, Taraki announced that the country would then move towards a bright socialist future along the path of Marxism-Leninism. In Moscow at that moment they believed in the possibility of a leap from feudalism to socialism, so they supported the new policy in every possible way. In Afghanistan, KGB representative offices were openly formed, in which Soviet specialists worked.

The reforms of the new government were typical for any communist regime. As part of the fight against inequality, the state attacked landowners - not only large, but also medium-sized ones, who were the majority among those affected by the redistribution of resources. Usury was abolished by special decrees; gave women equal rights with men, which meant coeducational schools and the abandonment of hijabs; established a minimum age for marriage. The communists abolished forced marriages and the custom of makhora (bride price), traditions whose roots went back centuries.

The conservative population, carefully preserving its traditions, reacted to the changes as expected and very radically: in the very first months, the new government faced armed resistance, which became increasingly cruel, gradually developing into a civil war. The leadership, which fanatically believed in the rapid achievement of socialism, responded with repression, involving the army in suppressing the uprisings. Those Afghans who did not go to the mountains with weapons fled the country in entire villages - during the years of PDPA rule, about a million people left Afghanistan. Soldiers and officers en masse went over to the side of anti-government groups. They were moving more and more confidently towards radical Islamic positions, with support from Iran and Pakistan, money for which was allocated by the United States. The head of the DRA, Mohammad Taraki, already at the beginning of 1979, first asked the USSR to send troops, but his request was not granted.

Holiday for soldiers in Afghan Shindad, October 1986

Photo: AP

The repressions increasingly resembled Stalin's terror: they affected not only opponents of the government, but also moderate socialists. Babrak Karmal, the leader of the moderate faction, had to flee the country. Soviet leaders realized that Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin was a dangerous and unpredictable fanatic, and tried to eliminate him with the hands of Taraki, but as a result, Amin survived the assassination attempt, removed Taraki and organized his murder. The death of his Afghan colleague shocked the Soviet leadership, especially Leonid Brezhnev.

Everything that happened destroyed the trust between Amin and the USSR authorities. Continuing to ask them for help and troops, he simultaneously began to improve relations with Pakistan, hoping to eventually change the country’s course and receive US support. The leaders of the Soviet Union could not come to terms with this.

Shortly after the storming of the palace and the assassination of Amin, Babrak Karmal, the leader of moderate socialists and the new head of the Afghan state, entered Kabul, accompanied by Soviet tanks. At the same time, the so-called “Limited Contingent of Soviet Troops in Afghanistan” (OKSVA) entering the country, according to official data, numbered up to 108 thousand soldiers.

"Politics of National Reconciliation"

In 1987, the implementation of the “policy of national reconciliation” began. At its plenum, the PDPA renounced its monopoly on power. A law appeared that allowed opponents of the government to create their own parties. The country has a new Constitution and a new president, Mohammed Najibullah. All these measures were taken to end the war through compromise and concessions.

At the same time, the Soviet leadership, led by Mikhail Gorbachev, set a course to reduce its own weapons, which meant the withdrawal of troops from the neighboring country. The Afghan war (1979-1989), in short, could not be waged in the conditions of the economic crisis that began in the USSR. In addition, the Cold War was already on its last legs. The USSR and the USA began to agree among themselves by signing numerous documents on disarmament and ending the escalation of the conflict between the two political systems.

Guerrillas of Allah

The locals, exhausted by the civil war, initially greeted the USSR troops joyfully - in some places people came out to greet them with flowers and flags - but this attitude did not last long. The Afghans fought their first battle in early January - an artillery regiment in the village of Nahrin mutinied and killed Soviet military advisers. The uprising was brutally suppressed - this was the first, but by no means the last episode of those that pushed the population to jihad.

The tribes of Afghanistan fought not only with foreign invaders - throughout history, the Pashtuns and other warlike peoples living in these sun-scorched mountains periodically carried out bloody massacres among themselves. Traditions of blood feud and clashes between tribes prevented the Afghans from uniting properly even when the state with radical socialists in power went to war against their foundations. However, the full-fledged invasion of the Soviet Union - hostile not only ideologically, but also religiously - forced the masses to rally under the black banner of jihad, a holy war against the infidels. In such a war there were not just dead people - the fallen were declared martyrs who died for their faith.

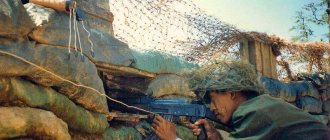

Insurgents load a mortar at a base in the Afghan mountains, 1988.

Photo: Nickelsberg / Liaison

Therefore, the Soviet soldiers, who in Afghanistan, as they say, were fulfilling their duty as internationalists, had to face a real guerrilla war: without a front line, without a clear division between militants and civilians - it was too difficult to find out how they really treated the “Shuravi” ” (“Soviet”) residents of the next village they occupied and at what moment the peaceful shepherd will take out a machine gun from the basement and begin to act like a mujahideen.

At the same time, in the ideological concept of the Soviet Union, partisans have always acted as noble freedom fighters opposing imperialism. The management understood how things were. Even before the deployment of troops, Yuri Andropov emphasized: “we would have to fight to a large extent with the people (...), fight against the people, crush the people and shoot the people.”

The people fought not far from their homes. The Mujahideen knew secret paths and gorges convenient for ambushes, escaped from encirclement, hid in caves and drew water from springs - or even descended from the mountains and hid among the civilian population. Attacking from ambush or on the sly, they often caught Soviet soldiers by surprise. They tried to win back through professionalism, organization and technical superiority - the 40th Army, of course, had both artillery and aviation at its disposal. But the Soviet units were equipped with too much equipment that was not adapted to fight the detachments scattered in the mountains, and simply did not have developed tactics for counter-guerrilla warfare. Working methods had to be developed on the spot, and weapons and equipment had to be modified there.

The enemy’s cunning was accompanied by conditions familiar to Afghans, but extremely difficult for an unprepared person: rarefied mountain air, fluctuating pressure, sandstorms, temperature differences from scorching midday heat to night cold—in some places the difference reached 40 degrees. Soldiers were threatened by poisonous snakes and insects, malaria, dysentery and hepatitis sent thousands of Soviet soldiers to hospital beds.

Soviet prisoners in a Mujahideen training camp in the mountains of Zabul province

Photo: Roland Neveu/LightRocket via Getty Images

The longer the war lasted, the more zinc coffins went to their mothers in the USSR, the more sticks with green and black flags - the graves of the Mujahideen - appeared along Afghan roads. The cruelty worsened - dushmans (from the word “enemy” in local languages) subjected captured internationalists to terrible torture, leaving their comrades with torn bodies to intimidate them. The Soviet soldiers became embittered in response and also allowed themselves a far from friendly attitude towards the local population.

Results

What are the results of the Afghan war? In short, Soviet intervention extended the life of the PDPA exactly for the period for which USSR troops remained in the country. After their withdrawal, the regime suffered agony. Mujahideen groups quickly regained their own control over Afghanistan. Islamists even appeared at the borders of the USSR. Soviet border guards had to endure enemy shelling after the troops left the country.

The status quo was broken. In April 1992, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was finally liquidated by Islamists. Complete chaos began in the country. It was divided by numerous factions. The war of all against all continued there until the invasion of NATO troops at the beginning of the 21st century. In the 90s, the Taliban movement appeared in the country, which became one of the leading forces of modern world terrorism.

In the mass post-Soviet consciousness, the Afghan war became one of the most important symbols of the 80s. Briefly for school, today they talk about it in history textbooks for grades 9 and 11. Numerous works of art - songs, films, books - are dedicated to the war. Assessments of its results vary, although at the end of the USSR the majority of the population, according to sociological surveys, were in favor of withdrawing troops and ending the senseless war.

Brothers in faith

But Muslims from neighboring regions empathized with the Afghans: as the commander of the Panjshir Gorge group, Jalaluddin Mokammal, recalled in a 2014 interview, the Mujahideen regularly received information about the plans of the Soviet troops. The traitors were not among the soldiers, but in the highest echelons of command and power. Among them was, for example, none other than Dzhokhar Dudayev - the future leader of the Chechen separatists then served at the air base in Bagram. In addition, according to Mokammal, information was provided by the heads of the southern republics of the USSR - for them, Afghanistan was a possible precedent for an eastern country leaving Soviet influence.

However, they were not the main helpers: Pakistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia had their own reasons for supporting the Islamists in Afghanistan - and they did this even before the introduction of OKSVA. Along the Afghan-Pakistani border, training camps were set up to train jihad warriors - both Afghans who had fled persecution and were planning to return, and radical youths from all over the Islamic world seeking to fight in the holy war.

In 1985, there were from 16 to 20 thousand such “internationalists” in the country. Among the foreign fighters was the future founder of Al-Qaeda (an international terrorist group banned in the Russian Federation) Osama bin Laden - in 1979 he dropped out of university in his native Saudi Arabia and went to Pakistan to participate in the fight against infidels.

Mujahideen in a training camp on the border near the city of Van, April 1984

Photo: Christopher Gunness/AP

Iran and the Saudis competed for authority in the Islamic world - just in those years, the world Islamic community was experiencing a new dawn of the idea of a global orthodox revolution, and leadership in promoting the ideas of jihad was an important task for the Arab states. In addition, Pakistan had not only a religious, but also a political interest that successfully coincided with it: helping the Mujahideen was an opportunity for them to get closer to a powerful superpower. The United States was most interested in the effectiveness of Afghan Islamists.

How many people died in the Afghan war?

If you believe official data, about 15 thousand Soviet soldiers did not return home to the USSR from Afghanistan. There are still 273 people listed as missing. More than 53 thousand soldiers were wounded and shell-shocked. The losses in the Afghan war for our country are colossal. Many veterans believe that the Soviet leadership made a big mistake by getting involved in this conflict. How many lives could have been saved if their decision had been different?

There are still ongoing debates about how many people died in the Afghan war. After all, the official figure does not take into account the pilots who died in the sky while transporting cargo, the soldiers returning home who came under fire, and the nurses and aides caring for the wounded.

Overseas assistants

The United States began supporting the Afghan opposition back in the 60s - it was in their interests to prevent the pro-Soviet regime from strengthening in the country. If you believe official documents, before the entry of Soviet troops into Afghanistan, Islamists received exclusively humanitarian aid from the Americans - medicines, food, uniforms.

But already from the beginning of 1980, the US authorities launched a full-fledged program to support the Mujahideen - and over the next months they began to receive as much from America as from Saudi Arabia. At first, they were not supplied with American weapons—the Islamists’ partners purchased Soviet weapons from Egypt and other countries. Among the suppliers was China, with which the USSR by that time had very tense relations.

The bulk of aid to Afghan groups came through Pakistan. As a result, the sanctions imposed on him in connection with the nuclear program were lifted, and already in 1980 they agreed on financial assistance in the amount of more than $100 million. The new deal, concluded the following year, called for more than $3.2 billion to be sent to Pakistan over five years.

Along with their weapons, the Mujahideen received cameras to film their attacks on Soviet troops - the recordings were a guarantee that assistance would continue. Basically, they were armed with those models of weapons that were suitable for Soviet ammunition - this is how the Islamists could supply themselves with the help of robberies.

Truck blown up by militants

Photo: AP

Soon the American administration stopped hiding the fact that it was operating in Afghanistan - they began sending the latest anti-aircraft missile systems and other weapons to the country. The volume of American support for the Mujahideen from 1980 to 1984, according to The New York Times, amounted to $625 million. In 1985, the United States provided Afghanistan with Stingers - they had entered service in the States just four years earlier, and at that time they had never been exported.

As Milton Bearden, who led the CIA station in Afghanistan and Pakistan from 1986 to 1989, recalls, the first group of Mujahideen was then taken to London for training - and already in September they for the first time shot down with American missiles a detachment of Soviet Mi-24 Crocodile helicopters, previously almost invulnerable for militant weapons. Many historians believe that this was one of the factors that deprived the USSR of hope for a final victory in Afghanistan.

Withdrawal of Soviet troops

Mikhail Gorbachev first announced the upcoming withdrawal of Soviet troops in December 1987, while on an official visit to the United States. Soon after this, the Soviet, American and Afghan delegations sat down at the negotiating table in Geneva, Switzerland. On April 14, 1988, following the results of their work, program documents were signed. Thus the history of the Afghan War came to an end. Briefly, we can say that according to the Geneva agreements, the Soviet leadership promised to withdraw its troops, and the American leadership promised to stop funding opponents of the PDPA.

Half of the USSR military contingent left the country in August 1988. In the summer, important garrisons were left in Kandahar, Gradez, Faizabad, Kundduz and other cities and settlements. The last Soviet soldier to leave Afghanistan on February 15, 1989 was Lieutenant General Boris Gromov. The whole world saw footage of how the military crossed and crossed the Friendship Bridge across the border river Amu Darya.

Not knowing the ford

Simultaneously with the failures in the war, the USSR began to understand that the initial assessment of the situation in Afghanistan was incorrect - in a huge number of aspects. The bet that the mere presence of Soviet troops would quell the turmoil was fundamentally wrong - Afghans, accustomed to seeing any foreign soldiers as invaders, increased their resistance, and those who had not previously joined the jihad now believed in the need for a holy war. In battles with the “infidels” people died - and their sons, brothers and fathers, following tribal traditions, swore revenge and went to the mountains - entire families, and in some cases entire villages.

Believing that peoples related to the Pashtuns and other Afghans would make them more understanding, the Soviet leadership initially recruited motorized rifle units mainly from conscripts from Central Asia - the share of Uzbeks, Turkmens, Tajiks and Kazakhs reached 60 percent. This also played the opposite role to what was expected - it turned out that the Pashtuns had historically been at enmity with some of the Soviet peoples, so their appearance on the territory of Afghanistan only aroused the greater anger of the Mujahideen.

A Soviet soldier drinks water from a local resident's bucket, 1986

Photo: Alexander Grashchenkov / RIA Novosti

In the end, the expectation that Babrak Karmal, who was more moderate than his predecessors, could change the situation in the country was also unjustified. He, however, although he weakened some radical reforms and canceled others, generally adhered to the same uncompromisingly socialist course as the country's previous leaders. In euphoria that the USSR had nevertheless sent troops, he did not make contact with other political forces, did not carry out proper work with the population, and even began to persecute and squeeze out of the government members of the more radical faction of the PDPA “Khalq”, instead of the union that The Soviet leadership was waiting for him.

In 1986, with Mikhail Gorbachev coming to power in the USSR, Karmal was removed from his post “for health reasons”, and he was replaced by the head of the Afghan state security service, Mohammad Najibullah. He immediately tried to establish contact with his citizens - he adopted a new constitution without mentioning socialism and communism, declared Islam the state religion and proclaimed a “policy of national reconciliation.” All this had some success, but over the years in power the PDPA lost the trust of the population - and the regime remained extremely shaky.

Statistical data

In total, according to the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, in the period from December 25, 1979 to February 15, 1989, 620 thousand Soviet military personnel served in Afghanistan. Of these, 525.2 thousand (including 62.9 thousand officers) served in the 40th Army, 90 thousand - in the border and other units of the KGB of the USSR, 5 thousand represented the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) ) THE USSR. In addition, about 21 thousand people were in civilian personnel positions in the troops.

According to a statistical study edited by Colonel General Grigory Krivosheev, “Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century,” the total irretrievable human losses of the Soviet side in the Afghan conflict amounted to 15 thousand 51 people. Control bodies, formations and units of the Soviet Army lost 14 thousand 427 people, KGB units - 576 people, formations of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs - 28 people. Other ministries and departments (Goskino, Gosteleradio, Ministry of Construction, etc.) lost 20 people. During the same period, 417 military personnel went missing or were captured in Afghanistan, of which at least 130 were released during the conflict and in subsequent years.

Over 200 thousand OKSV military personnel, as well as workers and civil servants, were awarded orders and medals. 86 Soviet military personnel were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for their courage and heroism (25 posthumously). According to official data, 147 tanks, 118 aircraft, 333 helicopters, 1,314 armored vehicles and 433 artillery systems were lost in the battles.

During the withdrawal, Soviet troops handed over free of charge to the Afghan side about 2 thousand 300 objects for various purposes, including 179 military camps (32 garrisons), left 990 armored vehicles, about 3 thousand cars, 142 artillery pieces, 43 rocket artillery installations, 82 mortars, 231 units of anti-aircraft weapons, 14.4 thousand units of small arms, 1 thousand 706 grenade launchers.

Diplomacy of War

From the very first days of the war, the international community called it an invasion - Pakistan, which turned into a “front-line state,” filed a complaint to the UN. France, England and Germany already in 1981-1982 offered the Soviet Union their solutions for a diplomatic settlement, but the “Kremlin elders” rejected them - the risk of the fall of the friendly regime was too great. Indirect negotiations in Geneva between representatives of Pakistan and Afghanistan began in 1982 and lasted 6 years.

The United States was in the greatest hurry to make a decision; the issue of the USSR's presence in Afghanistan was raised over and over again in Congress. At the beginning of the war, at the XXVI Congress of the CPSU they stated: “Imperialism has unleashed a real undeclared war against the Afghan revolution. This has created a direct threat to the security of our southern border. This situation forced us to provide military assistance."

Militants inspect the wreckage of a fallen Mi-17 helicopter, May 1988.

The Mujahideen said they shot down this Soviet-made Afghan army helicopter 16 kilometers from the border with Pakistan. The bases adjacent to this place, according to their statements, were evacuated the next day. . Photo: Sayed Haider Shah/AP

But, having abandoned the initial confidence in the forceful method, already in the fall of the same year the Soviet leadership took the first steps towards a diplomatic solution to the issue, and with the arrival of Yuri Andropov as General Secretary of the Central Committee, they drew up programs for peace initiatives.

However, one should not expect too straightforward diplomacy from the United States: despite all the statements, in fact the Americans were interested in continuing the Soviet-Afghan war. For them, it was a lever of constant political pressure on the USSR - therefore, the first attempts at diplomatic solutions were not simply ignored: after the first round of negotiations in 1982, President Ronald Reagan increased the volume of assistance to the Mujahideen.

As American researcher Stephen Galster wrote in 1988, in words the policy of the Reagan administration was aimed at finding an early solution through negotiations, but in fact the Americans increased military support for the Mujahideen, blocking any prospects for political solutions “as long as the Mujahideen want to fight.”

In 1998, Zbigniew Brzezinski, former national security adviser to President Carter, when asked whether he regretted helping Islamists in light of the civil war that continued after the Soviet departure, said: “Regret what? The covert operation was an excellent idea. As a result of its implementation, the Russians fell into an Afghan trap, and you want me to regret it?

Making a decision to send troops

On December 12, 1979, it became finally clear that the USSR would begin its own Afghan war. After briefly discussing the latest reservations in the documents, the Kremlin approved the operation to overthrow Amin.

Of course, hardly anyone in Moscow then realized how long this military campaign would drag on. But from the very beginning, the decision to send troops had its opponents. Firstly, Chief of the General Staff Nikolai Ogarkov did not want this. Secondly, Alexei Kosygin did not support the decision of the Politburo. This position of his became an additional and decisive reason for the final break with Leonid Brezhnev and his supporters.

Direct preparations for the transfer of the Soviet army to Afghanistan began the next day, December 13. The Soviet special services tried to organize an assassination attempt on Hafizzulu Amin, but the first pancake came out lumpy. The operation hung in the balance. Nevertheless, preparations continued.

Book of Memory

The day when the last units of the USSR left the lands of Afghanistan is moving further and further away from us. This war left a deep, indelible mark, stained with blood, in the history of our homeland. Thousands of young people who had not yet had time to see the life of the children did not return home. How scary and painful it is to remember. What were all these sacrifices for?

Hundreds of thousands of Afghan soldiers went through serious tests in this war, and not only did not break, but also showed such qualities as courage, heroism, devotion and love for the Motherland. Their fighting spirit was unshakable, and they went through this brutal war with dignity. Many were wounded and treated in military hospitals, but the main wounds that remained in the soul and are still bleeding cannot be cured by even the most experienced doctor. Before the eyes of these people, their comrades bled and died, dying a painful death from their wounds. Afghan soldiers have only the eternal memory of their fallen friends.

The Book of Memory of the Afghan War has been created in Russia. It immortalizes the names of heroes who fell on the territory of the republic. In each region there are separate Books of Memory of soldiers who served in Afghanistan, in which the names of the heroes who died in the Afghan War are written. The pictures from which young, handsome guys are looking at us make our hearts ache with pain. After all, none of these boys are alive anymore. “In vain the old woman waits for her son to come home...” - these words have been etched in the memory of every Russian since the Second World War and make the heart ache. So let the eternal memory of the heroes of the Afghan war remain, which will be refreshed by these truly sacred Books of Memory.

The results of the Afghan war for the people are not the result that the state achieved to resolve the conflict, but the number of human casualties, which number in the thousands.

The heroism of the Soviet soldier

The heroes of the Afghan war are probably known to many Russian citizens. I heard everything about their brave exploits. The history of the war in Afghanistan contains many courageous and heroic deeds. How many soldiers and officers bore the hardships and deprivations of military operations, and how many of them returned to their homeland in zinc coffins! They all proudly call themselves Afghan warriors.

Every day the bloody events in Afghanistan become more and more distant from us. The heroism and courage of Soviet soldiers is unforgettable. They earned the gratitude of the Afghan people and the respect of the Russians by fulfilling their military duty to the Fatherland. And they did it selflessly, as required by the military oath. For heroic deeds and courage, Soviet war fighters were awarded high state awards, many of them posthumously.

Afghan trace: a war that did not end for everyone

On February 15, 1989, the last Soviet units left the territory of Afghanistan. Before the bridge over the border river Amu Darya, Colonel General Boris Gromov, the future governor of the Moscow region and then commander of the Limited Contingent in Afghanistan, jumped from an armored personnel carrier to cross the border on foot. Izvestia special correspondents N. Sautin and V. Kuleshov were also present.

“Today, thousands of people gathered on the high bank of the Amu Darya are watching armored vehicles crossing the bridge connecting our country and Afghanistan. On the first armored personnel carrier under the guards banner is Lieutenant Alexey Sergachev, who started in Afghanistan as a simple soldier,” special correspondents wrote in the newspaper editorial on February 15, 1989.

However, Boris Gromov and the units that followed him were far from the last to leave Afghanistan - behind him there were still border guards and special forces who covered the departing troops (they would only be on Soviet territory by the evening of the same day), as well as several hundred military personnel who remained in the Afghan captivity.

The Afghan war, which lasted 10 years, from 1979 to 1989, cost the lives of thousands of Soviet troops - official statistics published back in 1989 estimated losses at 13 thousand people, but this figure did not take into account those who later died from wounds in hospitals . According to other researchers, losses could exceed 20 thousand people. Izvestia recalls what happened in Afghanistan in those years, why the Soviet Union decided to send troops, and how events in this country are connected with the large-scale geopolitical game that was started by the Russian and British empires.

How it all started

A year before the entry of Soviet troops, in 1978, a civil war began in Afghanistan. At the end of April, as a result of the April Revolution, the People's Democratic Party came to power in the country, proclaiming a democratic republic in the country and setting out to carry out a number of reforms. Representatives of the opposition, expressing the interests of the conservative Islamic world, spoke out against it. The political confrontation resulted in war. In 1979, the new leadership of Afghanistan turned to the USSR with a request for support, but the difficulties that such intervention threatened were so obvious that the Soviet leadership refused, although the Soviet garrison on the border with Afghanistan was strengthened for security purposes. In total, the Soviet leadership will receive about 20 such requests over the next year.

Around the same time, US President Jimmy Carter signed a secret decree under which the US provided support to opposition forces, including supplying the rebels with weapons and training in military camps.

However, in the fall of 1979, a split within the PDPA party was brewing in Afghanistan - on the orders of a member of the Politburo of the party’s Central Committee, Hafizullah Amin, its leader Nur Mohammad Taraki was arrested and then killed. Amin, having come to power, unleashed terror, which shook the position of the PDPA. Fearing that US-backed opposition forces, on whose side were the Mujahideen, would come to power in Afghanistan, the USSR decided to send troops and conduct an operation to overthrow Amin. Numerous letters previously sent by the Afghan leadership to the Soviet government were used as the reason.

Why the USSR was important to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, located at the junction of Central and South Asia, serves as a unique point of intersection of the interests of world powers fighting for dominance over the Central Asian region. It was the strategic location that historically attracted the attention of a number of states to the country.

For the USSR, the conflict in Afghanistan was all the more important because it borders on three countries that were then part of the Union - Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Unrest within the country could pose a threat to peace in the republics, and the coming to power of the opposition, supported by NATO forces during the Cold War, was even more undesirable.

However, the armed conflict of the 1980s, which resulted in a confrontation between the Soviet Union and Western countries, became a kind of continuation of a geopolitical dispute that lasted almost two centuries. At the beginning of the 19th century, the interests of the Russian Empire, which was expanding its presence in Central Asia in order to gain access to the goods of Asian peoples, as well as to stop raids on its southern territories, collided with the interests of the British Empire, which was interested in maintaining its influence in India and nearby territories. In the 1830s, Russian representatives won their first diplomatic victories in Kabul, followed by a series of Anglo-Afghan wars that lasted until almost the end of the century. By the beginning of the 20th century, the confrontation would remain rather at the level of intelligence, with the light hand of Rudyard Kipling receiving the name “Great Game”. By the end of World War II, the “game” would gradually fade away. But the conflict of interest will remain.

Operation Storm

At the end of 1979, when the start of the deployment of troops to Afghanistan was announced, the new Afghan president, Amin, thanked the USSR for the decision to provide military assistance and ordered assistance to Soviet troops. And in December of the same year, Soviet special forces launched Operation Storm - an assault on Amin’s Kabul residence.

On the afternoon of December 27, the presidential chef, Azerbaijani Mikhail Talibov, who was a KGB agent, poisoned the dishes served at dinner. When the President of Afghanistan and the guests felt unwell, the wife of the Afghan leader called doctors from the Soviet military hospital - unaware of the special operation being carried out, they provided assistance to everyone present.

In the evening of the same day, an assault began, as a result of which not only the presidential residence was captured, but also the buildings of the general headquarters of the Afghan army and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, communications centers, radio and television. Hafizullah Amin was killed. The Soviet military doctor Kuznechenkov, who was inside the palace at that moment, also died. Almost all the participants in the assault were wounded; in total, 20 Soviet soldiers died during the assault, as well as the leader of the operation, Colonel Boyarinov.

However, the main goal of the Soviet leadership was achieved - instead of Amin, Karmal, who collaborated with the USSR, was brought to Kabul, and the “second stage of the revolution” was proclaimed in the country.

Another "9th company"

Despite the fact that the Soviet contingent was in Afghanistan for ten years, active hostilities developed over five years - from March 1980 to April 1985. During this same five-year period, most of the most tragic events in the history of the Soviet contingent in the country occurred. And the biggest losses - over 2 thousand people - occurred in 1984.

On February 29, as part of the Kunar offensive, the first clash between airborne forces and mujahideen in the history of this war took place - in a battle with rebel units that had previously sided with government forces, 37 servicemen were killed, and the total losses for the raid amounted to 52 people. Later, experts noted that the reason for such large losses in this battle was the disorientation of the command in unusual terrain.

At the same time, the confrontation in the international arena also reached its peak - because of the conflict in Afghanistan, Western countries boycotted the 80 Olympics held in Moscow, and Soviet athletes did not go to the 84 Olympics held in Los Angeles.

Soviet military personnel had to fight in territory unfamiliar to them, which, however, was well known to members of local opposition-minded armed groups - the Mujahideen or Dushmans. However, the danger was not always associated with the actions of the Mujahideen. The tunnel at the Salang Pass acquired sad fame: on February 23, 1979, 16 military personnel suffocated in it due to a traffic jam, and three years later, in 1982, due to a traffic jam that formed outside the tunnel, almost 180 people died under its arches — 62 of them were Soviet military personnel. In 1985, another 17 people froze to death after their unit was forced to spend the night near a glacier in the Shutun Gorge.

The way home

The main condition for the withdrawal of troops to the USSR was the cessation of external interference in the internal life of Afghanistan. In 1983, talk about the withdrawal of troops began to be heard more and more often, at the same time the eight-month program for the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the territory of Afghanistan was almost completed, but due to the illness of Soviet leader Yuri Andropov, the issue was removed from the agenda. The end of the Afghan conflict was postponed for another five years - in April 1988, with the mediation of the UN in Switzerland, the Geneva Agreement on resolving the situation around the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was signed, the guarantors of which were the USSR and the USA. In accordance with the document, the USSR pledged to withdraw its contingent from May 15 to February 15, 1989, and the United States and Pakistan pledged to stop supporting the rebels.

Soviet units began returning to their homeland, for many of them this meant the beginning of a new life, for which they had to wait for many years.

“You won’t believe it, but life has turned out in such a way that my fiancée, Larisa Lobzhanidze, a student from Tiraspol, has been waiting for me for six years. Write: let him prepare for the wedding, I’m on my way,” Lieutenant Viktor Kapitan, political officer of the sapper company, shared with Izvestia correspondents who were present at the bridge over the Amu Darya.

However, not everyone will be able to survive the 10 months remaining before returning to their homeland. During the withdrawal of troops due to attacks by the Mujahideen, according to the American newspaper The Washington Post, about 500 more military personnel will be killed. Among them was Izvestia photojournalist, 29-year-old Alexander Sekretarev.

“He died in Afghanistan in May last year, when preparations for the withdrawal of our troops were just beginning. Sasha’s business trip was then extended until May 15. And how carefully he prepared! How I dreamed of being the best person to photograph the first convoy heading home for history! And, of course, I thought: I’ll film on May 15 and will definitely come here on February 15... These two dates were already connected by Geneva for all of us,” R. Armeev wrote about him in the issue of Izvestia on February 15, 1989, dedicated to the withdrawal of troops.

Remaining in Afghanistan

The Afghan war cost the lives of not only ordinary soldiers and officers, as well as civilian specialists, many of whom were captured or died during terrorist attacks organized in Kabul and other cities of the country, but also representatives of the command staff.

In 1981, while exiting an attack on an enemy command post, the helicopter in which Major General Khakhalov was located was destroyed—everyone on board died. In 1985, the Mujahideen shot down a MiG-21 fighter piloted by Major General Vlasov. The pilot managed to eject, but was captured after landing. To search for the general, the largest search operation of the entire war was launched, but it did not produce results - the general was shot in captivity shortly after his identity was established. In total, five Soviet generals were killed in Afghanistan.

And even after Boris Gromov crossed the symbolic Friendship Bridge across the Amu Darya in 1989, and the units covering the departing troops returned to their homeland, the Afghan war did not end for everyone.

According to official statistics, during the entire period of hostilities, 417 military personnel were captured. 130 of them were released before the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, but the conditions for the release of the rest were not specified in the Geneva Agreements. It is believed that about eight people were converted by the enemy, 21 people were released with the help of the Committee for the Rescue of Soviet Prisoners, created by Russian emigrants in the United States, and after their release they emigrated to the West. More than a hundred prisoners died, including while trying to escape from the camps on their own.

“There, beyond the Amu Darya, peace has not yet come. But there is still hope, and it is in the heart of every internationalist soldier of ours, that harmony in Afghanistan will be restored,” Izvestia correspondents N. Sautin and V. Kuleshov wrote on the day of the withdrawal of troops.

The Afghan conflict, which caused the deployment of troops in 1979, was never fully resolved—clashes in the country continue to this day.

We remember, we are proud...

The heroes of the Afghan war are not very willing to remember the events of the war years. They probably don’t want to reopen old wounds that still bleed if touched. I would like to highlight at least some of them, because the feat should be immortalized in years. The dead soldiers in the Afghan war deserve to be talked about.

Private N. Ya. Afinogenov was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union posthumously. He covered the retreat of his colleagues while performing an important combat mission. When he ran out of ammunition, he used his last grenade to destroy himself and the dushmans who were nearby. Sergeants N. Chepnik and A. Mironenko did the same when they were surrounded.

There are dozens more such examples of self-sacrifice. The unity of Soviet soldiers, mutual assistance in combat, and the solidarity of commanders and subordinates evoke special pride.

Private Yuri Fokin died trying to save the wounded commander. The soldier simply covered him with his body, preventing him from dying. Guard Private Yuri Fokin was posthumously awarded the Order of the Red Star. Soldier Komkov G.I. accomplished an identical feat.

The desire to carry out the order of the commander at the cost of one’s life, to protect one’s comrade, and to preserve military honor - this is the basis of all the heroic deeds of our soldiers in Afghanistan. The current defenders of the Motherland have someone to follow as an example. How many of our guys died in the Afghan war! And each of them deserves the title of hero.

The third stage of the war 1985-1987

The war is fought mainly by artillery and aviation. Another operation is being carried out in the Panjshir Gorge in response to the destruction of the Afghan army base by the opposition. In general, during the period from 1980 to 1985 of the war in Afghanistan, 4 battles were fought in this area between the 40th army and the Mujahideen. Their results were the temporary taking of control of the Panjshir Gorge by the 40th Army.

In February 1986, USSR Secretary General M.S. Gorbachev announces the start of developing a plan for the withdrawal of the 40th Army from Afghanistan. In March of the same year, US President Ronald Reagan announced the start of deliveries of the Stinger man-portable anti-aircraft missile system to the Mujahideen. From April 4 to April 20, 1986, the 40th Army carried out an operation to destroy the Javara base. A major defeat of the Mujahideen occurs. Ismail Khan’s troops are unsuccessfully trying to break through the “security zone” around Herat.

In March 1986, the 15th Brigade's operation was carried out. In it, the Jalalabad battalion, together with the Asadabad detachment, destroyed a large base of dushmans in the city of Karera. In August, the opposition led by Ahmad Shah Massoud defeated Afghan government troops in the city of Farkhar. In July, the Secretary General of the USSR again stated that it was necessary to send troops home and in October 1986, 6 regiments were withdrawn from the cities of Shindand, Kunduz and Kabul.

On October 26, 1986, the combat group of the 1st motorized rifle battalion of the 682nd motorized rifle regiment was forced to make a halt during an operation in the Shutul glacier area. At night, the temperature dropped significantly, as a result, 17 soldiers died from hypothermia overnight and 30 received frostbite. The main event of this period of the war in Afghanistan is the election of Mohammad Najibullah as the head of the country. Attempts are beginning to resolve the conflict politically.

The fourth stage and the beginning of the withdrawal of troops 1987 -1989.

The last stage of the war in Afghanistan also began with active military operations against the Mujahideen. Between February and March 1987, as many as 5 operations were carried out:

- "Strike" in Kunduz province;

- "Squall" near the city of Kandahar;

- "Thunderstorm" in the Ghazni region, as well as the latest operation "Circle" in the provinces of Kabul and Logar.

On April 9, three groups of dushmans attacked the border outpost of the 117th detachment and were repulsed. A few days later, Soviet troops destroyed a rebel base in Nangarhar province.

Several successful raids against dushmans are also carried out. The 40th Army begins to use the Barrier system to cover the eastern and southeastern sections of the border. On November 23, 1987, during Operation Magistral, the city of Khost was unblocked.

In January 1988, the famous battle of the 9th company of the 345th parachute regiment with the Mujahideen took place. The troops managed to defend height 3234 in the province of Paktia. The main event of this year was the Geneva Agreement on a political settlement of the situation in the DRA. Their result was that the Soviet Union pledged to withdraw the 40th Army from Afghanistan within nine months, starting on May 15.

The United States and Pakistan, for their part, had to stop supporting the Mujahideen. Already on June 24, 1988, opposition forces captured the center of Wardak province - the city of Maidanshahr, and on August 10, the Mujahideen took Kunduz. On January 23-26, 1988, the last Soviet military operation in Afghanistan, called Typhoon, was carried out. Its goal was the destruction of Ahmad Shah Massoud. Large-scale bombing and artillery attacks on Mujahideen positions were carried out. On February 4, 1989, the last unit of the Soviet Army left the city of Kabul, and already on the 15th of the same month, Soviet troops were completely withdrawn from Afghanistan.