Root Causes

The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 began a period of conflict that devastated southeastern Europe until 1918 and continued there in one form or another until the 21st century. These Balkan Wars arose from the aspirations of the nationalist states of Southeastern Europe; Having previously achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire during the 19th century, these states wanted to unite with representatives of their nationalities remaining under Ottoman rule and thus achieve their maximum nationalist aspirations.

Thus, the states of Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia sought to emulate the nationalist successes of 19th-century Germany and Italy.

Competing claims to Ottoman-held territories, especially Macedonia, made it difficult for the Balkan states to cooperate against the Ottomans. However, when the Young Turks threatened to revive the Ottoman Empire after a coup in 1908, the leaders of the Balkan states sought ways to overcome their rivalry. Russian diplomacy contributed to their efforts.

The Russians wanted to compensate for their failure in the Bosnian crisis of 1908-1909 by creating a pro-Russian Balkan Alliance designed to prevent further advance of Austria-Hungary in the region. In March 1912, the Bulgarians and Serbs entered into an alliance under the auspices of Russia. This agreement contained a plan for resolving the Macedonian problem, including a provision for Russian mediation. The Bulgarians and Serbs then made individual agreements with the Greeks and Montenegrins, who also reached an agreement together. By September 1912, this loose confederation, the Balkan League, was ready to achieve its goals.

Prerequisites

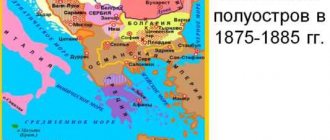

The peoples of the Balkan Peninsula developed under the rule of Rome and then Byzantium. In the 15th century, the Ottoman Turks began to penetrate their territory. Over several centuries, the peoples of the Balkans organized uprisings against the Turkish empire many times, but suffered defeats.

In 1911, the Turkish-Italian War began. The Ottomans lost in it, showing the world their weakness. But even in this state, the Turkish army was stronger than the army of each individual Balkan country.

Russia took the side of the conquered countries, which sought to weaken Turkey. She supported the formation of a military alliance. It was she who won independence for Bulgaria in the Russian-Balkan War (Russian-Turkish).

First Balkan War

Montenegro started the First Balkan War on October 8, 1912. Before the other allies could join, the Ottomans declared war on the Balkan League on October 17. The main theater of the ensuing conflict was Thrace (the historical region of Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey).

While one Bulgarian army besieged the main Ottoman fortress of Adrianople (Edirne), two others won major victories at Kirkkilis (Turkish: Kirklareli, Bulgarian: Lozengrad) and Bunar Hisar/Luleburgaz. The latter was the largest battle in Europe between the Franco-German War of 1870-1871 and the First World War. The Ottomans rallied at Chatalci (a district of Istanbul province), the last line of defense before Constantinople. The exhausted and epidemic-ridden Bulgarians' attack on the Ottoman positions there on November 17 failed. Both sides then moved on to trench warfare at Çatalja.

Elsewhere, the Serbian army defeated the western Ottoman army at Kumanovo on 23 October. The Serbs then advanced against weakening resistance into Macedonia, Kosovo and further through Albania, reaching the Adriatic coast in December. The Greek fleet prevented the Ottomans from delivering reinforcements from Anatolia to the Balkans and occupied the Ottoman islands of the Aegean Sea.

The Greek army advanced in two directions, entering Thessaloniki on November 8, and further west, besieging the city of Ioannina. Montenegrin troops entered the sanjak (administrative region) of Novi Pazar and besieged the Northern Albanian city of Scutari (Shkodër).

The Ottomans signed a truce with Bulgaria, Montenegro and Serbia on December 3. Greek military operations continued. By this time, Ottoman Europe was limited to the three besieged cities of Adrianople, Ioannina and Scutari, the Gallipoli Peninsula and Eastern Thrace beyond the Chataldji Line. As a result of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, groups of Albanian aristocrats, supported by Austria and Italy, declared the independence of Albania on November 28, 1912.

While delegations from the Balkan Allies attempted to negotiate a final peace with the Ottomans in London, a conference of ambassadors from the Great Powers met in London to ensure that their interests would prevail in any Balkan settlement.

The coup of January 23, 1913 returned the Young Turk government to power in Constantinople. This government was determined to continue the war, mainly to retain Adrianople. She condemned the January 30 truce. Hostilities resumed to the detriment of the Ottomans. Ioannina fell to the Greeks on March 6, and Adrianople to the Bulgarians on March 26.

However, the siege of Scutari caused international complications. The Austrians demanded that this predominantly Albanian city become part of the new Albanian state. Under pressure from Austria-Hungary, the Serbian troops who had helped the Montenegrins in the siege retreated. However, the Montenegrins continued the siege, and on April 22 they managed to take the city. A Great Power flotilla off the Adriatic forced the Montenegrins to retreat less than two weeks later, on May 5th.

Meanwhile, in London, peace negotiations culminated in the Preliminary Treaty of London, signed on May 30, 1913, between the Balkan allies and the Ottoman Empire. Under this treaty, the Ottoman Empire in Europe consisted only of a narrow strip of territory in Eastern Thrace, defined by a straight line drawn from the Aegean port of Enos to the Black Sea port of Midia.

Results

As a result of the Balkan War, Turkey lost its territories in Europe, except for Constantinople and its environs. The lands came under the control of the allied countries. Negotiations were held, as a result of which Albania gained independence.

The members of the Balkan Union had to decide on the distribution of lands received as a result of the peace treaty independently, without outside interference. The inability to make compromise decisions led to a new Balkan War.

Second Balkan or Inter-Allied War

During the First Balkan War, while the Bulgarians fought most of the Ottoman army in Thrace, the Serbs occupied most of Macedonia. Austrian prohibitions prevented the Serbs from obtaining the Adriatic port in northern Albania that they wanted. The Serbs then attempted to strengthen their position in Macedonia as compensation for the loss of the Albanian coast. The Greeks never agreed to any settlement regarding Macedonia, and also indicated that they would retain the Macedonian areas that they occupied. The Bulgarians were still determined to gain this territory. Hostilities between the allies on the Macedonian issue escalated in the spring of 1913 from the exchange of notes to actual shooting. Russian attempts at mediation between Bulgaria and Serbia were pathetic and fruitless.

On the night of 29–30 June 1913, Bulgarian soldiers launched local attacks on Greek and Serbian positions in Macedonia. These attacks signaled the start of a general war. Counterattacks by the Greeks and Serbs pushed the Bulgarians back to their pre-war borders. As soon as the Bulgarian army began to stabilize the situation, Romanian and Ottoman units invaded Bulgaria. The Romanians sought to gain Southern Dobruja in order to expand their Black Sea coast and balance the Bulgarian conquests elsewhere in the Balkans.

The Ottomans wanted to retake Adrianople. The Bulgarian army, already actively fighting against the Greeks and Serbs, was unable to resist the Romanians and Ottomans. Under these conditions, Bulgaria demanded peace. As a result of the Treaty of Bucharest, signed on August 10, Bulgaria ceded most of Macedonia to Greece and Serbia, and southern Dobruja to Romania. The Treaty of Constantinople, signed on September 30, 1913, ended Bulgaria's brief occupation of Adrianople.

***

So far, the actions of the authorities of the Republika Srpska and the member of the Presidium of BiH from the Serbian people, Milorad Dodik, are more like bargaining. For example, the entity’s budget for 2022 does not include a single euro for the exercise of powers, which the republic seems to want to return from the level of the central authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Even the solemn parade on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Republika Srpska, which took place on January 9 in Banja Luka, now the main city of the Republika Srpska, was fundamentally called a “procession” by the authorities, emphasizing its peaceful nature

True, the main participants in the parade were still units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republika Srpska, who marched with automatic weapons. And the public’s particular delight was caused by the passage of a convoy of a special anti-terrorist unit in “Despot” armored vehicles, which are produced in the city of Bratunac near Srebrenica.

But although only veterans of the Republika Srpska Army took part in the procession, everything could change in a year. It is not for nothing that during the celebration of Republika Srpska Day on January 9, 2022, the then Patriarch of Serbia Irinej declared that “now we have gathered to glorify the newest state of the Serbian people.”

Resulting consequences

The Balkan wars resulted in enormous casualties. The Bulgarians lost about 65,000 people, the Greeks - 9,500, the Montenegrins - 3,000, the Serbs - at least 36,000. The Ottomans lost up to 125,000 people killed. In addition, tens of thousands of civilians died from disease and other causes. Deliberate atrocities occurred in all theaters of war.

Another important consequence of the Balkan Wars was the alienation of Bulgaria from Russia. Until 1913, Bulgaria was the most important Russian satellite state in the Balkan region. Bulgaria's proximity to Constantinople gave Russia a valuable base from which to exert pressure on this vital area. The failure of Russian diplomacy to mediate the Bulgarian-Serbian dispute over the location of Macedonia led to Bulgaria's disastrous defeat in the Second Balkan War and Bulgaria's subsequent recourse to the Triple Alliance for compensation. Thus, Serbia remained Russia's only ally in the Balkans. When Austro-Hungarian reprisals threatened Serbia in July 1914, the Russians had to defend Serbia or lose the Balkans entirely.

The ambitions of the Montenegrins and Serbs in Albania greatly increased Austria-Hungary's antipathy towards these two South Slavic states. The Viennese government was firmly determined that Serbian power in the Balkans should not increase. Three times, in December 1912, April 1913 and again after the Balkan Wars in October 1913, the Austro-Hungarians came into conflict with the Serbs and Montenegrins over Albanian issues.

Although the war ended in the summer of 1914 as a result of events in Bosnia, conflicts around Albania influenced the Austrians' decision to fight the Serbs. The First World War was not the third Balkan War; rather, the Balkan Wars were the beginning of the First World War. Nationalist conflicts continued in Southeastern Europe from 1912 to 1918. Problems of nationalism have persisted there into the 21st century.

Fight for rights

In the fall of 1990, the first free elections to local parliaments on a multi-party basis were held in all republics of the SFRY, in which completely new forces that took shape during 1990 won. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, these were the national parties: Muslims (Party of Democratic Action, SDA), Croats (Croatian Democratic Community, HDZ) and Serbs (Serbian Democratic Party, SDP).

Of course, intercommunal tensions had previously played an important role in the life of Bosnian society, but the communist regime actively fought against all attempts by intellectuals to put national problems at the forefront. But, as the famous Russian Balkanist Georgy Engelhardt notes, only the political liberalization of 1990 gave the national intelligentsia in Bosnia and Herzegovina the opportunity to structure themselves and carry out political mobilization under national slogans.

Unfortunately, this mobilization almost from the first day acquired an anti-Serbian character

In the spring of 1990, the first multi-party democratic elections were held in Croatia, and on May 30, 1990, the Croatian Parliament was formed based on the results of the vote

Photo: National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia

This is not surprising, because SDA leader Aliya Izetbegovic wrote in his “Islamic Declaration” back in 1970: “Islamic order can only be established in those countries where Muslims make up the majority of the population. Otherwise it will come down to intentions.” Therefore, the election of Izetbegovic as chairman of the Presidium of BiH with the support of the Croats in 1990 was regarded by the Serbs as an immediate threat.

Since April 1991, the process of so-called regionalization began in BiH - the unification of communities controlled by the SDP into the Serbian Autonomous Regions (SAO). The largest of them were the Bosnian Krajina and Eastern Herzegovina, later the Northern Bosnia (with its center in Doboj) and Birac (it included Serbian settlements in the Drina valley, in Muslim-majority communities).

In October 1991, Muslim and Croat deputies in the Assembly (parliament) of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina actually carried out a coup. Thus, the Constitution of this union republic stated that it is “a sovereign democratic state of the peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina - Muslims, Serbs, Croats and representatives of other nations.” However, on October 12, 1991, deputies from the SDA and HDZ, in the absence of their Serbian colleagues, adopted the “Memorandum on the Sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina,” in which Muslims and Croats were presented as state-forming peoples, and Serbs as a minority, effectively reduced to an ethnic-cultural group. At the same time, Serbs in BiH made up almost a third of the population, there were almost twice as many of them as Croats.

After this, the split of Bosnia and Herzegovina became inevitable. On October 24, 1991, in the city of Pale near Sarajevo, deputies of the BiH parliament from the SDP and other Serbian political parties proclaimed the creation of the Assembly of the Serbian people of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the transfer to the authority of this body of all Serbian autonomous regions of the republic. The deputies also adopted the “Declaration on the preservation of the Serbian people in the united state of Yugoslavia.” Serbs living in BiH supported this declaration with an overwhelming majority in a referendum on November 9-10, 1991: 85 percent of Bosnian Serbs took part in the plebiscite.

98%

Those who voted in a referendum in November 1991 were in favor of maintaining the Serbian part of Bosnia and Herzegovina as part of Yugoslavia

President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegovic, accompanied by General Rasim Delic (right) and Sakib Makhmulin (left), greet those present at the military parade

Photo: Peter Andrews/Reuters

It was on the basis of the results of the expression of popular will that the Assembly of the Serbian People in BiH on January 9, 1992, on the basis of the SAO, proclaimed the creation of the Republika Srpska (RS) within BiH, and itself as the People's Assembly (parliament) of the RS. By the way, the current member of the Presidium of BiH from the Serbian people, and then a deputy from the Serbian “reformists” Milorad Dodik, also voted for these decisions, that is, he is one of the few active politicians who stood at the origins of the Republika Srpska.

On February 28, 1992, the Constitution of the Republika Srpska was adopted, the government of the RS was approved and its presidium (a kind of collective president) was elected, consisting of Radovan Karadzic, Biljana Plavsic and Nikola Kolyevich. At the same time, in fact, from the first days the republic was led by Radovan Karadzic - as the leader of the SDP, which had an overwhelming majority of votes in the Assembly of the RS.