An ax is not only about chopping wood or building a house without a single nail. An ax is also a terrible weapon. In the old days, it was used by both mere mortals and kings, and in the late Middle Ages, the ax even became a weapon of foot knightly combat, like its distant relative, the polex. Not a single classic medieval tournament took place without this weapon. We talk about how the best people of their time used axes.

“In a dark basement, in a winding pit Fight with axes, fight with axes!..” - group “Helmet”

An ax is like royalty

Nowadays, a knight is associated primarily with powerful armor, clumsiness and, of course, a sword. However, the gentlemen of the classical Middle Ages were very fond of not only the spear, sword and armor, but also often used an ax. And they used it so effectively that by the 15th-16th centuries it evolved into a more advanced version - polex.

The ax was used on the battlefield not only by ordinary knights, but also by kings. Thus, an English king named Stephen broke his sword during the Battle of Lincoln in 1141, after which he grabbed a large Danish ax and bludgeoned his enemies with it until the shaft broke. Only after this they were able to capture the king. An even more significant case occurred in 1314 with the Scottish king Robert I Bruce, known to the general public from the Mel Gibson film “Braveheart”.

Statue of Robert the Bruce. Bannockburn

In the very battle with which the film ends, a curious episode occurred. At the very beginning of the Battle of Bannockburn, when the king was conducting reconnaissance with a small detachment, he was noticed by the English knight Sir Humphrey de Bohun. Seeing an opportunity to capture the enemy king, the Englishman rushed to the attack with a spear at the ready. But the Scotsman did not have a spear. Not at all embarrassed, Robert the Bruce pulled out an ax and, dodging the blow, met the enemy with all his might with a blow to the helmet.

If you imagine the speed of a knight attacking on horseback and multiply it by the power of the oncoming blow with an axe, it will be clear why the ax shaft broke. But the enemy was even less lucky - the helmet was crushed along with the head of the brave knight. In honor of this feat, the statue of King Robert in Bannockburn depicts him with an axe.

Danish axe/Brodex

Quite a frightening and formidable weapon. To use such a unique ax, it was necessary to have a very large and complex technical base, but this is only a small part of what was required of a warrior. As a rule, this ax was owned by the Vikings, who had a large physical mass, because the weapon reached a length of two to three meters and weighed up to one and a half kilograms. Such an ax was used to deliver blows “to kill,” that is, performed with one swing. Only in case of a bad hit did the enemy manage to survive. But real warriors rarely missed, because the Vikings were taught the art of wielding an ax by their fathers from a very early age.

Also, the Danish ax was used as a cunning means of weakening the enemy, because when a blow was struck on the shield, the ax got stuck in it, thereby creating an additional load. Thus, the enemy either instantly got rid of the means of protection, or continued the battle with the enemy ax in the shield. All this made him slow down in his actions and lose physical strength in battle. After some time, the enemy became easy prey for the Viking.

However, such a significant disadvantage as a very low defense ability is a weak point and Achilles heel for any Norman who wields a Danish axe. After all, it was a fairly heavy and voluminous weapon, which was difficult to maneuver in conditions of tough confrontation. However, later Brodex began to be used in European countries to protect borders from enemy raids.

Often, the Vikings carved designs on a Danish ax that reminded them of their home, family and main values in life. Some particularly creative Normans themselves made this type of bladed weapon. It is not for nothing that in Scandinavian mythology it was believed that only a homemade ax could bring success in battle. Therefore, many Vikings tried to create it themselves. However, at that time only the most skilled craftsmen could make an ax, who were familiar with old military weapons, knew how to work with a blade and apply unusual patterns to the handle. Sometimes the making of an ax was entrusted to a specially trained blacksmith who was familiar with various types of axes, knew their typology and could easily make a military weapon decorated with a beautiful pendant. Moreover, especially for the Vikings, craftsmen also often made pendants on which mini-copies of their axes were placed.

Jacques de Lalaine - a fierce master of ax fighting

Jacques de Lalen

But not only kings skillfully wielded axes. The 15th-century Walloon knight Jacques de Lalaine became famous for his tournament exploits. Remember the name of this clever bastard: most of this text is devoted to his fights. And very often he won, holding in his hands the polex we mentioned - a hybrid weapon, a knight's battle ax for a foot fight.

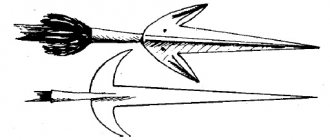

Imagine a faceted shaft 150-210 cm long, bound with iron strips and sometimes even having a small round shield to protect your hands. On the warhead most often there was a small ax, plus a hammer on the other side, as well as a long faceted spike-edge, which could be used to perfectly stab the enemy into the cracks of the armor. Sometimes, instead of a hammer, a curved spike in the form of a beak could appear, and in some cases the beak was adjacent to the hammer, and there was no ax blade at all. At the other end of the shaft, a steel spike was often also attached with this part for injections.

This is the kind of monster Jacques de Lalen used to beat his opponents during tournaments. Although they also did not lag behind.

Polex

The story of the brave de Lalen is known to us from the 15th century manuscript “Chronicle of the Knight Jacques de Lalen” by George Castellan. The most curious thing is that battles on poleaxes were so widespread that training manuals were even published on them. For example, in 1495, an instructor at the Guild of St. Mark named Peter Falkner from Frankfurt am Main wrote his fencing textbook, calling it Kunste Zu Ritterlicher Were. In it, the master described not only the usual fights with swords, spears, poles, daggers and dueling shields, but also paid attention to combat with poleaxes.

But most of all about polex is written in a 15th-century treatise by an unknown Milanese master who lived at the court of the Burgundian Duke Charles the Bold. The treatise is simply called Le Jeu de la Hache (“Games with an Axe”).

There is an impression that Jacques de Lalen read this treatise in between battles and beatings of knights on the lists. Especially considering that our knight served at court without fear or reproach and was the favorite of the same Charles the Bold.

Distant ancestor of the battle ax

The ancestor of the battle ax was the two-edged labrys, which originated in Ancient Greece and is a symbol of divine power. The functions of these weapons were combat, religious, and ceremonial. Since it was very difficult to make such weapons, they were available only to kings and priests.

An ax with two blades arranged in a butterfly pattern on either side of the shaft required enormous strength and dexterity to use in battle. A warrior armed with a labrys and covered with a shield was invincible and, in the eyes of those around him, was endowed with divine strength and power.

How Jacques de Lalen mocked the Scots

Illustration from “Kunste Zu Ritterlicher Were”

Many lines from “Ax Games” are devoted to knocking the ax out of the enemy’s hands. For example, paragraph 18 of this treatise reads:

“If he wants to stab you in the face with the tip of his axe, you need to strike sharply to knock the ax out of his hands.”

And Jacques loved to deprive his opponents of their axes. For example, on December 15, 1445, a duel took place between our hero and the Italian knight errant Jean de Boniface. At the beginning of the battle, the opponents threw spears at each other, but both dodged them perfectly, and the half-axes went into action.

The Italian began to furiously bludgeon his opponent with an ax, but that was not the case - with masterful techniques, Jacques constantly knocked the polex out of his hands. Finally, he knocked out the enemy’s weapon so far that he did not have time to rush after him, and rushed to fight. But this maneuver also failed - de Lalen deftly jumped back and was about to smash the head of his unarmed opponent with a blow from the polex, when the Duke of Burgundy, who was present at the lists, stopped the fight.

But the Italian was still lucky. In 1449, our hero, along with two other knights, fought in Scotland in a triple battle against local masters. De Lalen inherited James Douglas, brother of the Earl of Douglas. In front of the very eyes of King James II of Scotland and six thousand spectators, James first lost his spear, knocked out by an enemy's ax, and then the ax in the same way. Infuriated by such public humiliation, Douglas pulled out a dagger and struck his opponent in the unprotected face, but he did not succeed either - Jacques intercepted the blade with a glove near his own face, and the opponents began to fight. The Scotsman was also not so great as a wrestler, so Lalen eventually abandoned him and was about to stab him, but the king stopped this mockery of his subject.

Hit it on the head and the rest will fall apart on its own.

Apparently Jacques de Lalaine gave Ax Games to his friends to read. For example, in the same triple battle with the Scots, another knight, Jacques’s friend, the British Esquire Evre de Meradec, also performed well. He clearly read paragraph 22 of “Games with an Axe,” which reads:

“No matter what defense you are in, you can try to hit your opponent on the head...”

Evreux tried it. And more than once. His opponent was James Douglas Jr., who immediately poked his opponent in the face with a spear. The Briton put out his hand and the spear bounced off the plate protection. After this, de Meryadek did not lose his head and, with all his might, hit his opponent’s head with an ax. So hard that he collapsed, stunned, and his helmet received a huge dent.

The Briton was about to help one of his friends when he suddenly noticed that Douglas had stirred and began to rise. He was in vain - Evre flew at his opponent and began to woo him so much that the king was forced to stop this fight, seeing how his subject was being turned into crumpled canned food.

Parameters of double-sided axes

Double-edged axes are characterized by the following features:

- extended handle made of wood;

- good balance, allowing you to deliver confident blows;

- a hard blade made from alloys that can withstand prolonged and constant stress.

Modern models with two cutting edges, which are used for household purposes, are made of carbon steel. The sizes of such products vary depending on the area of application. One edge is more finely ground than the other. This difference is due to the fact that the products are used to solve two problems simultaneously. One edge is used for cutting trees, the other for splitting.

Wrestling techniques are no hindrance to the ax

The treatise also contains techniques that allow you to drop your opponent to the ground. For example, paragraph 17 reads:

“Also, if he comes with an ax head to thrust, you can also point the crosshairs of the ax at him [in the same manner as he does]. When you see him take a step forward, you will need to step behind him as far as you can without him finding you in front of him. And when you take a step back, strike and press the tail of your ax on his neck so that he falls forward ... "

Jacques de Lalen knew how to do this too. The duel we will talk about took place in 1449 in Flanders, and his opponent was Thomas Ke, an English knight who decided to challenge the famous Walloon.

The fighters entered the lists slightly different in armament - the Englishman wore a closed helmet with a beak-shaped visor, the Walloon was much more easily protected, his helmet left his face and neck open. Also, the resident of Ke took a polex with a greatly elongated spike, thus outgunning the enemy.

This did not bother Lalen. He rushed at the enemy, aiming the lance of his ax at his face - the helmet held out, and Thomas unleashed all his fury on de Lalen, trying to reach him with all parts of the weapon, but in vain. Here the lightness of the helmet played a role, since Jacques saw everything perfectly, breathed well and defended himself well, while the enemy got tired much faster due to the thick visor and more powerful armor.

Having waited until his opponent was tired, the Walloon began to hit his opponent’s helmet as hard as he could, and when he finally took the lead, he rushed into the fight, hoping to drop the clumsy carcass. And here Thomas’s weapon played a cruel joke - a longer lance pierced de Lalen’s left hand like a butterfly on a needle, falling into the gap in the glove.

A variant of a helmet with a visor that can be stuck into the ground

But our hero, despite the blood and pain, continued to defend himself under the onslaught of the revived enemy. When Thomas raised his ax high above his head, hoping to split the Walloon's head and helmet with a heroic blow, he poked him in the unprotected armpit with a spike. Taking advantage of the enemy's hesitation, Jacques de Lalen grabbed his head with his right hand and pulled him towards himself so powerfully that the Englishman fell face forward with a roar. At the same time, his beak-shaped visor was stuck so deeply into the ground that he was unable to rise without outside help.

Russian squads in battle. Part 6

Combat techniques

Chronicles telling about wars and battles are very stingy with small details. Chroniclers conveyed the general course of events and noted features, for example, especially stubborn, brutal battles. Therefore, they cannot tell us about fighting techniques. Eastern and Byzantine authors are also stingy with such details.

As a result, researchers are forced to turn to historical reconstruction. Another source can be the Scandinavian sagas. Scandinavian warriors were close to Russian warriors in both weapons and fighting techniques. It is clear that the sagas as a source for the reconstruction of events are very unreliable. Critical analysis is required. But nevertheless, the researchers were able to isolate some data, and they are close to objectivity. In addition, for the writer of a saga, describing a battle is not an end in itself; the motives of the conflict and the behavior of the heroes are usually described. The author will say: the hero “swung his sword”, “cut off his leg”, “struck a blow”, but how the warrior moved, how exactly he struck, we will not learn from the saga.

Modern amateurs make copies of ancient weapons, defensive weapons, and try to imitate battles and individual fights. Military historical reconstruction has become a very widespread phenomenon in our time. However, it is also far from real combat, like conventional, sports “martial” arts. Real military skills, like martial arts, were aimed at destroying the enemy. This seriously changes the psychology of battle. There are other details that greatly distinguish a modern reconstruction from a real battle. The weapon is blunt, which increases the safety of participants, but reduces the reliability of the use of the weapon. It becomes heavier than it was in ancient times. This is especially true for swords. In addition, in modern reconstruction, armor and protective weapons are widely used. And the percentage of warriors in the ancient Russian army who had helmets, not to mention chain mail and plate armor, was small. The head was protected by an ordinary hat. Howl from the countryside came to fight in ordinary clothes. In more ancient times, the Slavs could fight naked. The only massive defensive weapon was the shield. Warriors without armor were threatened not by blunt weapons and club comrades, but by real enemies and sharp spears, sabers and axes.

Therefore, modern historians can provide only a few details that can be called reliable. Where did the Russian warrior study? As previously reported, ancient man got used to weapons from early childhood. A knife, an ax, a bow, a hunting spear and a flail were everyday household items, protection from animals and dashing people. Every family had one weapon or another, and often had to use it. Children were accustomed to weapons with the help of children's bows, spears, etc. The high level of general physical fitness of the Russian people was supported by life and culture itself. People were constantly engaged in physical activity. Negative mass social diseases, such as alcoholism and drug addiction, were absent in principle. Elements of folk culture such as festive dances and fist fights also helped to maintain high physical readiness.

It is obvious that in the princely and boyar squads military skills were purposefully developed. Professional warriors were freed from the need to engage in production and trading activities. Having free time made it possible to purposefully develop strength, endurance, agility, and develop combat skills. The squad also trained a shift of youths. Anyone who was systematically worked with from childhood became a professional warrior, whose skills sharply distinguished him from those around him. Thus, “The Saga of Njal,” describing one of the best warriors of Iceland, Gunnar, reports that he could cut with both his right and left hands, was good at throwing spears and had no equal in archery. “He could jump fully armed to more than the height of his height and jumped back no worse than forward...”

An ancient warrior could demonstrate his skills in two cases - in an individual duel and, which happened much more often, in the ranks. From written sources we know that individual fights were common in Rus'. Thus, in the Russian state there was a practice of judicial duels, when in defense of one’s honor and dignity one could fight oneself, or put up a specially trained fighter. The justice of God's court, the “field” (judicial duel), was recognized in Rus' until the 16th century. Usually such a duel took place when both sides had equal evidence, and the truth could not be determined in the usual way. The “fight of truth” has existed since ancient times and was a legacy of the primitive era.

We also know about cases of hand-to-hand combat on the battlefield - this is a duel between a Kozhemyaki youth and a Pecheneg (992). But perhaps the most famous such fight is the fight between Peresvet and Chelubey before the start of the Battle of Kulikovo. Apparently, this was a classic battle of heavily armed horsemen, the elite of the armed forces of the time. They were armed with long cavalry spears, and in this battle the main technique of heavily armed mounted spearmen was used - a ramming blow.

In individual fights, most often the ratio of weapons was approximately equal - both warriors had a shield and a sword, or an ax. Sometimes one side might use a spear. Usually the warrior held a weapon in his right hand, a shield in his left hand in front of him. There was a certain stance. It is believed that the fighter stood half-turned towards the enemy on slightly bent legs, covering most of the body with a shield (except for the head and legs below the knee). The Rus had round shields with a diameter of approximately 90 cm. Chopping blows with a sword or ax were applied with great force and amplitude. Icelandic sagas tell of severed limbs, severed heads and bodies. When striking, the warrior tried not to move the shield too far to the side, so as not to open himself up to the enemy’s attack. In a one-on-one fight, the legs were perhaps the most vulnerable point of a fighter. Round shields allowed for good maneuverability, but did not cover the entire body. The warrior had to guess the direction of the enemy's strike in order not to get hit, or lower the shield down. It should be noted that sword-to-sword fights without shields are not noted in the sources. Swords of that time, the Carolingian type with their small hilt and massive pommel, were not intended for fencing.

The main area of application of combat skills was combat. It’s not for nothing that wall-to-wall combat was widespread in Russia until the beginning of the 20th century. It was this kind of battle that taught combat. He taught how to withstand an enemy's blow, not break formation, and developed a sense of comradeship and camaraderie. The basis of the ancient Russian “wall” is an infantryman armed with a sword, ax, spear and protected by a shield. The formation could be dense to prevent enemy cavalry from breaking through. In this case, in the front ranks there were warriors armed with spears, including spears. With the help of spears they stopped war horses and dealt with warriors in armor of all degrees of protection. The infantry formation might not have been too dense. To have the opportunity for maneuverable combat with a shield. This concerned infantry-infantry combat and small detachments. At the same time, the formation should not have been too stretched - the opening was too large to support the neighbor and those in the other row. In combat there was no place for one-on-one knightly fights; they beat the opponent who was closer. In addition, a determined and experienced enemy could wedge itself into an opening that was too large and destroy the battle formation, which was fraught with demoralization and flight.

Battles began with the use of throwing weapons. Based on examples of battles between the British and the French, it is known that bows could also play a decisive role in the battle. In a large battle, hitting the enemy was not as difficult as hitting a single target. Therefore, if the concentration of archers on one side was significant, the other side could suffer heavy losses even before the melee began. There was only one salvation in such a situation. Cover yourself with shields and quickly attack, quickly closing the distance with the enemy. And it was generally impossible to effectively fight with mounted detachments of archers without having the same detachments. It must be said that archers could be used not only at the initial stage of the battle. Already during the battle, archers from the back rows could fire at the enemy.

As the battle formations drew closer, sulits were used - darts and throwing spears. Technically, throwing a light spear looked like this. The fighter held the sulitsa approximately in the area of the center of gravity and sent it to the target. The spear was not directed straight forward, but slightly upward, in order to set the optimal flight path, which ensured the greatest flight range. Sulitsy warriors rushed from a distance of 10-30 meters.

Psychological weapons such as the battle cry were also used in battle. Thus, the Byzantine historian Leo the Deacon talks about the battle cry of the Russian soldiers of Prince Svyatoslav Igorevich during the battle of Dorostol: “The Dews, guided by their innate brutality and rage, rushed in a furious outburst, roaring like those possessed, at the Romans (the inhabitants of Byzantium called themselves “Romans” ", i.e. "Romans" - the author)...". The battle cry was of great importance. Firstly, for both pagans and Christians, it was an appeal to higher powers, gods (God, saints). The cry was a legacy of an ancient era. A warrior of hoary antiquity went into battle with the name of his patron god. "One!" - among the Scandinavians. The warrior could be killed at any moment, and the last thought was very important. The thought of a warrior god was a “path” to the world of the gods. Secondly, the cry was a kind of key word that introduced the squad, the army, into a special psychological state, a “combat trance.” Thirdly, the cry had a certain moral impact on the enemy. Finally, the battle cry was a means of strengthening the morale of soldiers and contributed to the unity of the army, where all fighters felt like one whole. And the unity of the army was the key to victory.

In close combat, the first row takes the main blow. They tried to place heavily armed warriors, warriors in chain mail and plate armor. Usually the first row, like the second, was filled with spearmen. The warriors covered themselves with shields and struck with spears, swords and shields. We must not forget that warriors usually had more than one type of main and auxiliary weapons. For example, a spear and an axe, a sword and an ax (chaser, mace, etc.). They tried to hit whoever opened up with weapons. We tried to keep several opponents in sight at once and keep an eye on our neighbors to the right and left in order to come to their aid if necessary.

In close combat, the ax and sword were used in a similar way. But there were several differences in their working technique. The cutting surface of the sword is higher and its weight is greater than that of an axe. The sword requires a large amplitude of impact. In addition, the sword is more likely to be hit due to the length of the blade. The ax was smaller and required the warrior to strike quickly and accurately. The lighter weight of the ax made it possible to act quickly, change the direction of the blow, and widely use deceptive movements. At the same time, the energy of the ax's blow is such that even when blunted, it can cause heavy damage to the enemy.

The second rank, which operated under the cover of the first rank, was also massively armed with spears. The spear did not require much room for maneuver and made it possible to deliver quick and accurate strikes to any exposed part of the enemy’s body. Usually the spear was used for stabbing. Although in some cases they could also deliver slashing blows. But special spears were suitable for this, with long and wide tips that had extended side surfaces. Spear warriors also worked not against one, but against several opponents. Hitting the one who opened up. Piercing blows to the face were especially dangerous. In the second row, wide-bladed axes with long handles could also be successfully used. Such weapons were well suited for delivering strong slashing blows. At the same time, the protruding angle of the blade could be used to stab the enemy in the face.

We must not forget the fact that the southern Russian squads from the beginning of the 11th century were predominantly mounted. However, it is almost impossible to restore equestrian combat using the method of modern historical reconstruction. This is due to the impossibility of preparing real war horses, and the war horse itself was a weapon. According to epics, it is known that the horses of heroes took part in battles. There is also no possibility for full-fledged, long-term training of mounted warriors; such a need has long disappeared.

Historians can only guess with a relative degree of probability how mounted warriors fought in Rus'. Ramming spear strikes were widely used. At the same time, judging by the stories of sources, the spear often broke. Then they used sabers, swords, axes, maces, flails and other weapons. Apparently, the tactics of using detachments of horse archers, inherited from the Scythian-Sarmatian era, played some role.

Tactics and strategy

We know more about the tactics and strategy of the ancient Rus than about combat techniques. Quite a lot can be learned from Byzantine authors, since Rus' and the Slavs were constant opponents of the Byzantine Empire. The Romans carefully recorded their wars with their enemies. It is clear that these texts must be subjected to careful analysis. The Byzantines tend to exaggerate their own merits and downplay the achievements of the enemy. It happens that dozens of Romans and hundreds, thousands of opponents die in battles.

Procopius of Caesarea noted that the Slavs of the 6th century were masters of “partisan”, sabotage warfare. Dwellings are built in remote, hard-to-reach places, protected by forests, swamps, rivers and lakes. Slavic warriors skillfully set up ambushes and launched surprise attacks on the enemy. They used various military tricks. The Slavs were good swimmers and skillfully crossed bodies of water. Slavic scouts skillfully hid under water, using reeds hollow inside for breathing. Slavic warriors were armed with spears, including throwing spears (sulits), bows, and shields.

Another Byzantine author, commander and emperor Mauritius the Strategist speaks about the use of “guerrilla” tactics by the Slavs in the 6th century: “Leading a life of robbery, they love to attack their enemies in wooded, narrow and steep places. They use ambushes, surprise attacks and tricks to their advantage, night and day, inventing numerous tricks.” The author clearly lied about the “robbery” life. Especially if you take into account the expansion of Byzantium itself into the lands inhabited by the Slavs.

Byzantine authors note that the Slavic troops “do not strive to fight in a proper battle, nor do they want to show themselves in open and level places.” In principle, such tactics were determined by the tasks that the Slavic squads solved. The Slavic princes in that period (the so-called “era of “military democracy”) were aimed at seizing spoils, rather than waging a “correct” war and seizing territory. Therefore, there was no need for “general battles” with the Byzantine troops. In order to successfully complete the task, the squad had to suddenly invade enemy territory, devastate certain areas and quickly leave without engaging in battle with the troops sent against them.

The Byzantine historian who lived at the beginning of the 7th century, Theophylact Simocatta, gives an example of a successful Slavic ambush. So, when the Roman commander-in-chief, the brother of the emperor, without conducting appropriate reconnaissance and not believing that there could be an enemy nearby, orders the troops to begin crossing. When the first thousand soldiers crossed the river, it was destroyed by the “barbarians.” It was an old, proven technique - to strike at the enemy’s crossing without waiting for the entire enemy army to cross the shore.

Sources report that the Russians skillfully used ships in war. An important role in the fighting of the Slavs was played by light river vessels - single-shafted boats. They were called so because each vessel was based on one large hollowed out (scorched) tree trunk. As needed, sides were added from boards; such vessels were called nadsads. The Slavs also had ships of the “river-sea” class - lodya (longships). In almost all Russian-Byzantine wars we see the use of fleets by Russian soldiers. Their main function was transport - they transported soldiers and cargo. The boat could carry 40 - 60 people. The number of flotillas reached several hundred ships, and sometimes 2 thousand. The use of such flotillas sharply increased the mobility of the Russian army, especially in conditions where the region was saturated with rivers and lakes. The Black Sea was so mastered by the Russians that it was called Russian.

The need to resist the mounted detachments of the steppes quickly made the mounted squads an important part of the Russian army. As noted above, from about the 11th century, the basis of the army in Southern Rus' was the horse squad. Judging by the rapid movement of Svyatoslav’s army, he was already using cavalry en masse, including auxiliary cavalry - Pecheneg and Hungarian. And he transported infantry using ships. Mounted warriors were mainly heavily armed warriors who had several types of weapons (spear, sword, saber, axe, mace, flail, etc., depending on the warrior’s preferences). But there were also lightly armed archers. Thus, both the experience of Byzantium, with its heavily armed cavalry - cataphracts, and the use of fast, lightly armed horsemen capable of sudden attacks by the steppes were used.

Battle of Novgorod and Suzdal in 1170, fragment of an icon from 1460.

However, under Svyatoslav, the basis of the army was still infantry. And the prince himself preferred to fight on foot. During this period, the Rus fought in close formation on foot - a “wall”. Along the front, the “wall” was about 300 m and reached 10-12 ranks in depth. Well-armed warriors stood in the first ranks. The flanks could be covered by cavalry. When attacking, the “wall” could be built as a ramming wedge, with the most experienced and well-armed warriors advancing at the tip. It was very difficult to overturn such a “wall” even for the heavy Byzantine cavalry. In the decisive battle with the Romans near Adrianople in 970, the less combat-ready cavalry flanks of Svyatoslav's troops - the Hungarians and Pechenegs - were ambushed and overturned, but the main Russian-Bulgarian forces continued the offensive in the center and were able to decide the outcome of the battle in their favor.

In the XI-XII centuries, the Russian army will be divided into regiments. As a rule, in the center of the battle formation stood an infantry regiment - urban and rural militias. And on the flanks are the horse squads of princes and boyars (regiments of the left and right hands). By the end of the 12th century, to the division of three regiments along the front, a division of four regiments in depth was added. An advanced or guard regiment will appear in front of the main forces. In the future, the main forces could be supplemented by a reserve, or an ambush regiment.

Point in the face - the author's work

Jacques de Lalaine also had his own favorite technique, which I did not find in both manuals on ax fighting. He first used it in March 1450, when he again fought the Italian Jean de Boniface. After exchanging several series of blows with axes, Jacques grabbed the enemy's polex with his right hand, pulled him back and pierced him three times with the spike-point in the visor. Then he grabbed the stunned Italian by the feathers on his helmet and yanked him to the ground, winning the victory.

In June of the same year, Burgundian esquire Gerard de Roussaillon was unlucky to meet Lalen. He wore an open helmet for the fight, and when Jacques performed exactly the same technique as with the Italian, the edge of the ax wounded his opponent’s unprotected face so deeply that the judge immediately stopped the fight.

In October, Lalen tried to carry out the same technique against Esquire Claude Pitois, but he, having already heard about the enemy’s attack, managed to block it, grabbing the Walloon’s ax with his hand. After that, Jacques grabbed his opponent’s neck with his hand, but even then Claude escaped the hold, but fell into a tighter grip and flew to the ground from the throw. True, at the same time he managed to catch the enemy, and both crashed to the ground. The victory was awarded to Jacques, since Claude touched the ground first.

Excellent in the art of war, including ax fighting, our hero won many fights and gained the fame of an invincible fighter. So invincible that only a cannonball could stop him. While storming the Flemish city of Ghent, Jacques de Lalaine was killed by a cannon shot. Apparently, nothing else simply took him. So, on July 3, 1453, at the age of 32, one of the best knights in Europe and a great fan of beating people with an ax passed away under the roar of cannonade.

Legendary Viking weapons

Normans, Vikings, Varangians - words that terrified all the peoples inhabiting Europe, since the world did not know more bloodthirsty and powerful warriors at that time.

Armed with Scandinavian axes, otherwise called Danish or heavy battle axes, the Vikings did not know defeat in battle and always took rich booty and took away captive slaves.

The main difference between this weapon was its wide, heavy blade, which could instantly cut off a person’s head or limbs. Mighty warriors masterfully wielded axes for battle, work, and tournaments.

In Kievan Rus, which had close trade ties with the Scandinavian countries, battle axes looked like siblings of the Viking axe. For the Russian foot army, axes and axes were the main type of weapons.