The names of the knights of the Middle Ages have forever entered our history. They are covered with the spirit of early Christianity, poetic courage, honor and nobility. Of course, the romantic image of knights does not entirely correspond to reality, but they, without a doubt, made a significant contribution to the development of history.

The knightly traditions turned out to be so strong that even after the disappearance of this class, the honorary title remained. In some countries, knighting still exists.

Ulrich von Liechtenstein (1200-1278)

Ulrich von Liechtenstein did not storm Jerusalem, did not fight the Moors, and did not participate in the Reconquista. He became famous as a knight-poet. In 1227 and 1240 he made travels, which he described in the courtly novel “Serving the Ladies.”

According to him, he walked from Venice to Vienna, challenging every knight he met to battle in the name of Venus. He also created The Ladies' Book, a theoretical work on love poetry.

Lichtenstein's "Serving the Ladies" is a textbook example of a courtly novel. It tells how a knight sought the favor of a beautiful lady. To do this, he had to amputate his little finger and half of his upper lip, defeat three hundred opponents in tournaments, but the lady remained adamant. Already at the end of the novel, Lichtenstein concludes “that only a fool can serve indefinitely where there is nothing to count on for reward.”

Respect must be earned

There are royal nicknames with which everything is simple and clear. It is hardly necessary to explain, for example, why Charles , Peter and Catherine are Great. There are no questions for Vladimir the Saint and Alexander II the Liberator . Alexander Nevsky and Dmitry Donskoy received nicknames in honor of the places where they became famous on the battlefields. Everything is clear with Ivan the Terrible .

Article on the topic Vasily the Dark - the triumph of a loser.

How a weak ruler strengthened Russia With Vasily the Dark and Vsevolod the Big Nest is already more complicated.

The first was blinded by opponents during an internecine conflict, and the second became famous for a large number of descendants. And yet, Russian monarchs with nicknames were, by and large, lucky. Unlike foreign “colleagues”.

Why was there so much less respect for kings in the West? This is often due to the stability of a particular dynasty on the throne. The worse the monarch controlled the situation in the country, the less respected he was. And when the dynasty changed, the predecessors were not favored at all. But sometimes, at first glance, dissonant nicknames actually paid tribute to one or another positive qualities of the ruler.

Harold Hare's Foot, 14th century miniature. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

Richard the Lionheart (1157-1199)

Richard the Lionheart is the only king knight on our list. In addition to the well-known and heroic nickname, Richard also had a second one - “Yes and No.” It was invented by another knight, Bertrand de Born, who christened the young prince so for his indecisiveness.

Already being king, Richard was not at all involved in governing England. In the memory of his descendants, he remained a fearless warrior who cared about personal glory more than the well-being of his possessions. Richard spent almost the entire time of his reign abroad.

He took part in the Third Crusade, conquered Sicily and Cyprus, besieged and took Acre, but the English king never decided to storm Jerusalem. On the way back, Richard was captured by Duke Leopold of Austria. Only a rich ransom allowed him to return home.

After returning to England, Richard fought with the French king Philip II Augustus for another five years. Richard's only major victory in this war was the capture of Gisors near Paris in 1197.

Order of the Dragon

At the beginning of the 15th century, the Hungarian king Sigismund I of Luxembourg faced opposition from the local nobility, who wanted a change of ruler. During the internal struggle, he remained in power, suppressing the rebellious representatives of the nobility. To further combat possible opponents and more closely unite his associates, Sigismund I established the Order of the Dragon. At first the number of its members was small, then it increased.

Raymond VI (1156-1222)

Count Raymond VI of Toulouse was an atypical knight. He became famous for his opposition to the Vatican. One of the largest feudal lords of Languedoc in Southern France, he patronized the Cathars, whose religion was professed by the majority of the population of Languedoc during his reign.

Pope Innocent II excommunicated Raymond twice for refusing to submit, and in 1208 he called for a campaign against his lands, which went down in history as the Albigensian Crusade. Raymond offered no resistance and publicly repented in 1209.

However, in his opinion, the demands on Toulouse that were too cruel led to another rift with the Catholic Church. For two years, from 1211 to 1213, he managed to hold Toulouse, but after the defeat of the crusaders at the Battle of Mur, Raymond IV fled to England, to the court of John the Landless.

In 1214 he again formally submitted to the pope. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council, which he attended, deprived him of his rights to all lands, leaving only the Marquisate of Provence to his son, the future Raymond VII.

Death of the army

On the Fourth of July they marched towards the city, and the crusaders met them at Hattin. Guy de Lusignan intended to defeat the Arabs with one powerful blow, but the cunning Salah ad-Din constantly retreated, exhausting the soldiers. The names of the knights of the Middle Ages, which have survived to this day, are covered not only with glory, but also with shame. Raymond Buck and Laoditius de Tiberias became cowardly and fled to the Muslims.

Largely thanks to this betrayal, the crusaders suffered a crushing defeat.

William Marshal (1146-1219)

William Marshal was one of the few knights whose biography was published almost immediately after his death. In 1219, a poem entitled The History of William Marshal was published.

The marshal became famous not because of his feats of arms in wars (although he also took part in them), but because of his victories in knightly tournaments. He gave them sixteen whole years of his life.

The Archbishop of Canterbury called the Marshal the greatest knight of all time.

Already at the age of 70, Marshal led the royal army in a campaign against France. His signature appears on the Magna Carta as the guarantor of its observance.

Ludovic the Stutterer

The Franks were especially merciless towards their monarchs. For example, Louis the Stutterer , king of the West Frankish kingdom, Aquitaine, Lorraine and Provence, was the youngest son of the glorious king Charles the Bald .

Louis the Stutterer was not in good health and, moreover, due to a speech impediment, he could not quickly express his orders and wishes. At the same time, he repeatedly rebelled against his father, and in the end he turned out to be the only one of the sons of Charles the Bald who managed to outlive his parent. True, not for long: Louis the Zaika, who suffered from a whole bunch of illnesses, after two years of rule, died in April 879 at the 33rd year of his life.

Eric the Lisp, fragment found at Goodham Abbey. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376)

Eldest son of King Edward III, Prince of Wales. He received his nickname either because of his difficult character, or because of the origin of his mother, or because of the color of his armor.

The “Black Prince” gained his fame in battles. He won two classic battles of the Middle Ages - at Cressy and at Poitiers.

For this, his father especially noted him, making him the first Knight of the new Order of the Garter. His marriage to his cousin, Joanna of Kent, also added to Edward's knighthood. This couple was one of the brightest in Europe.

On June 8, 1376, a year before his father's death, Prince Edward died and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral. The English crown was inherited by his son Richard II.

The Black Prince left his mark on culture. He is one of the heroes of Arthur Conan Doyle's dilogy about the Hundred Years' War, a character in Dumas's novel "The Bastard de Mauleon".

Beautiful lady in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages were a magical time. It is the transformation of the image of a woman from an inconspicuous companion of a man in the early Middle Ages into a mysterious and beloved Beautiful Lady in the High Middle Ages that seems magical. The tradition of worshiping the image of the Beautiful Lady originated in the French province of Provence and is rooted in the veneration of the Virgin Mary. Love for an earthly woman became more and more sublime and acquired poetic shades. In the Middle Ages it was believed that such love becomes a source of valor and virtue for a warrior. One of the legends said: “It is not often that a knight accomplishes many feats and achieves glory if he is not in love.”

Bertrand de Born (1140-1215)

The knight and troubadour Bertrand de Born was the ruler of Périgord, owner of the castle of Hautefort. Dante Alighieri portrayed Bertrand de Born in his "Divine Comedy": the troubadour is in Hell, and holds his severed head in his hand as punishment for the fact that in life he stirred up quarrels between people and loved wars.

And, according to Dante, Bertrand de Born sang only to sow discord.

De Born, meanwhile, became famous for his courtly poetry. In his poems, he glorified, for example, Duchess Matilda, the eldest daughter of Henry II and Alienora of Aquitaine. De Born was familiar with many troubadours of his time, such as Guilhem de Bergedan, Arnaut Daniel, Folke de Marseglia, Gaucelme Faidit and even the French trouvère Conon of Bethune. Towards the end of his life, Bertrand de Born retired to the Cistercian Abbey of Dalon, where he died in 1215.

Godfrey of Bouillon (1060-1100)

To become one of the leaders of the First Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon sold everything he had and gave up his lands. The pinnacle of his military career was the storming of Jerusalem.

Godfrey of Bouillon was elected the first king of the Crusader kingdom in the Holy Land, but refused such a title, preferring the title of baron and Defender of the Holy Sepulcher.

He left orders to crown his brother Baldwin king of Jerusalem in the event that Godfrey himself died - this is how an entire dynasty was founded.

As a ruler, Godfrey took care of expanding the boundaries of the state, imposed taxes on the emissaries of Caesarea, Ptolemais, Ascalon and subjugated the Arabians on the left side of the Jordan to his power. On his initiative, a law was introduced that was called the Jerusalem Assisi.

He died, according to Ibn al-Qalanisi, during the siege of Acre. According to another version, he died of cholera.

Pepin the Short

The majordomo, and then the first king of the Franks from the Carolingian dynasty, is a champion in terms of giggling from Russian schoolchildren and students. In fact, from the point of view of the Franks, his name was unremarkable. As for the nickname Short, it was naturally explained by his short stature.

Article on the topic

Fall of Kyiv.

How Yuri Dolgoruky changed the fate of Russia By the way, the Russian prince Yuri Dolgoruky was also short and his disproportionately long arms looked extremely unattractive.

But in Rus' they found a beautiful nickname for the prince, and the Franks decided not to indulge in poetic comparisons. The more than quarter-century reign of Pepin the Short was quite successful. Having founded a new royal dynasty, he prepared all the conditions for his son, Charlemagne, who became the main hero of the Western European Middle Ages.

John the Soft Sword, miniature from a manuscript of 1300-1400. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

Jacques de Molay (1244-1314)

De Molay was the last Master of the Knights Templar. In 1291, after the fall of Acre, the Templars moved their headquarters to Cyprus.

Jacques de Molay set himself two ambitious goals: he wanted to reform the order and convince the pope and European monarchs to launch a new Crusade to the Holy Land.

The Templar Order was the richest organization in the history of medieval Europe, and its economic ambitions were beginning to thwart European monarchs.

On October 13, 1307, by order of King Philip IV the Fair of France, all French Templars were arrested. The order was officially banned.

The last Master of the Tramplars remained in history thanks in part to the legend of the so-called “curse of de Molay.” According to Geoffroy of Paris, on March 18, 1314, Jacques de Molay, having mounted the fire, summoned the French king Philip IV, his adviser Guillaume de Nogaret and Pope Clement V to God's court. Already shrouded in clouds of smoke, he promised the king, adviser and pope that they will survive it for no more than a year. He also cursed the royal family to the thirteenth generation.

In addition, there is a legend that Jacques de Molay, before his death, founded the first Masonic lodges, in which the prohibited Order of the Templars was to be preserved underground.

Defender of the Kingdom of Heaven

Ballian Ibelin managed to escape capture and return to Jerusalem. After this, Salah ad-Din’s troops approached the city. The siege began, and Balian led the garrison. At that time, only fourteen knights remained in Jerusalem.

To raise morale, Baron Ibelin gathered the townspeople and ordered all the squires to kneel and knighted them all. The names of the knights of the Middle Ages, the list of which increased to sixty, went down in history forever. For the next six days, the Saracens stormed the city, but without success. Despite the overwhelming majority, they failed to take the city; the Christians were able to surrender it on favorable terms. Everyone was given the right to leave the city. The Holy Sepulcher remained under the personal guard of Salah ad-Din.

Jean le Maingre Boucicaut (1366-1421)

Boucicault was one of the most famous French knights. At 18 he went to Prussia to help the Teutonic Order, then he fought against the Moors in Spain and became one of the heroes of the Hundred Years' War. During the truce in 1390, Boucicaut competed in a knight's tournament and took first place in it.

Boucicault was a knight errant and wrote poems about his valor.

His was so great that King Philip VI made him Marshal of France.

At the famous Battle of Agincourt, Boucicault was captured and died in England six years later.

Poems about love:

An innumerable number of poems and songs were composed by minstrels about valiant knights and their beautiful ladies. The troubadours believed that only love can transform a person. Love and beauty have always occupied a central place in their poems - the beauty of nature and the Lady of the Heart.

Here are just a few of them:

I met you, Donna, and instantly the Fire of love penetrated my chest. Since then, not a day has passed without that fire burning me.

(Arnaut de Mareil)

How good my knight is! I belong entirely to him. How sweet it is to my heart when I hug him! He who has made the whole world fall in love with himself with his high valor will be dear to me forever!

(Burggraf von Regensburg)

Sid Campeador (1041(1057)-1099)

The real name of this famous knight was Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar. He was a Castilian nobleman, a military and political figure, a national hero of Spain, a hero of Spanish folk legends, poems, romances and dramas, as well as the famous tragedy of Corneille.

The Arabs called the knight Sid. Translated from folk Arabic, “sidi” means “my master.” In addition to the nickname "Sid", Rodrigo also earned another nickname - Campeador, which translates as "winner".

Rodrigo's fame was forged under King Alfonso. Under him, El Cid became commander-in-chief of the Castilian army. In 1094, Cid captured Valencia and became its ruler. All attempts by the Almorravids to reconquer Valencia ended in their defeats in the battles of Cuarte (in 1094) and Bairen (in 1097). After his death in 1099, Sid became a folk hero, sung in poems and songs.

It is believed that before the final battle with the Moors, El Cid was mortally wounded by a poisoned arrow. His wife dressed Compeador's body in armor and mounted it on a horse so that his army would maintain its morale.

In 1919, the remains of Cid and his wife Doña Jimena were buried in the Burgos Cathedral. Tizona, a sword believed to have belonged to Sid, has been located here since 2007.

Tristan and Isolde

Tristan was born into a royal family. His mother died immediately after giving birth, barely having time to give her son a name. Hiding from the machinations of his stepmother, the prince ended up in Cornwall at the court of King Mark, where he received the education befitting a knight. In those days, Cornwall was forced to pay a heavy tribute to the King of Ireland Morhult - one hundred girls and boys every year. When the mighty Morkhult once again came for tribute, young Tristan, unexpectedly for everyone, challenged him to a duel. In the very first cavalry clash, Tristan cut off Morkhult’s helmet with a mighty blow and overthrew him.

Unfortunately, the enemy's spear was poisoned and the wounded knight was on the verge of death. Cornwall was spared tribute, but the young hero’s strength was rapidly dwindling. King Mark secretly sent his warrior to Ireland, to Isolde Blonde, who was skilled in healing. The girl cured Tristan and love broke out between them.

At the same time, King Mark, unaware of this, wooed Isolde, who was the daughter of the new king of Ireland. Tristan fulfilled the will of his master and brought his beloved to him. On the advice of a faithful friend, on the first wedding night, instead of Isolde, her maid was on the king’s bed. Later, when the deception was revealed, Mark expelled Tristan from the country. The young knight went to Britain and helped its king defeat the treacherous enemy who had besieged his castle. In gratitude, King Hoel offers him his daughter as his wife, who, by a strange coincidence, is also named Isolde. Tristan does not dare refuse and White-armed Isolde becomes his wife. However, the knight, true to his feelings for his beloved, does not get close to his wife. Later, when Tristan is mortally wounded in a new battle, neither the doctors nor his wife are able to help him. Feeling that life is leaving him, he asks his friend to bring his beloved to him at any cost. As a conditional sign, he asks his friend to raise a white sail on the ship if Isolde is with him and a black one if not.

The cunning helps the envoy to kidnap Isolde and, under a white sail, his ship enters the harbor. Unfortunately, Tristan's jealous wife finds out about everything and, when her husband asks her to tell what sail is on the ship, she says that its color is black. Out of unbearable grief, the hero shouts three times “Isolde, dear!” and dies. Isolde goes ashore and, seeing her lover dead, hugs him and her soul leaves her body.

They were buried next to each other. The next morning, the townspeople discovered a green, fragrant thorn tree that rose from Tristan’s grave and grew into Isolde’s grave.

William Wallace (c. 1272-1305)

William Wallace is a national hero of Scotland, one of the most important figures in its wars of independence in 1296-1328. His image was embodied by Mel Gibson in the film “Braveheart”.

In 1297, Wallace killed the English Sheriff of Lanark and soon established himself as one of the leaders of the Scottish rebellion against the English. On September 11 of the same year, Wallace's small army defeated a 10,000-strong British army at Stirling Bridge. Most of the country was liberated. Wallace was knighted and declared Guardian of the Realm, ruling on behalf of Balliol.

A year later, the English king Edward I again invaded Scotland. On July 22, 1298, the Battle of Falkirk took place. Wallace's forces were defeated and he was forced into hiding. However, a letter from the French king to his ambassadors in Rome dated November 7, 1300 has been preserved, in which he demands that they provide support to Wallace.

Guerrilla warfare continued in Scotland at this time, and Wallace returned to his homeland in 1304 and took part in several clashes. However, on August 5, 1305, he was captured near Glasgow by English soldiers.

Wallace rejected accusations of treason at trial, saying: “I cannot be a traitor to Edward, because I was never his subject.”

On August 23, 1305, William Wallace was executed in London. His body was beheaded and cut into pieces, his head was hung on the Great London Bridge, and his body parts were exhibited in Scotland's largest cities - Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth.

Henry Percy (1364-1403)

For his character, Henry Percy received the nickname "hotspur" (hot spur). Percy is one of the heroes of Shakespeare's historical chronicles. Already at the age of fourteen, under the command of his father, he participated in the siege and capture of Berwick, and ten years later he himself commanded two raids on Boulogne. In the same 1388, he was knighted of the Garter by King Edward III of England and took an active part in the war with France.

For his support of the future king Henry IV, Percy became constable of the castles of Flint, Conwy, Chester, Caernarvon and Denbigh, and was also appointed justiciar of North Wales. At the Battle of Homildon Hill, Hotspur captured Earl Archibald Douglas, who commanded the Scots.

Henry Percy's conflict with Henry IV over the latter's refusal to pay the army's expenses led to Hotspur releasing Douglas without ransom.

The English king declared Percy a traitor. As a result, Henry Percy, along with his father and uncle, joined Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion in July 1403. On July 21, Henry was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury against the royal army.

His body was buried in Winchester, but 2 days later it was dug up and put on public display in Shrewsbury, and Henry's severed head was hung on the gates of York.

Interesting fact: the London football club Tottenham is also called the “hot spur” in honor of Henry Percy.

Knights and chivalry of three centuries. Part 5. Knights of France. Central and southern regions

The ranks of knights were mixed, there were hundreds of them, and everyone struck and attacked, using their weapons.

Who will the Lord choose and send success to? There you could see deadly stones, a lot of torn chain mail and cut armor, and how spears and blades both wound and sting. And the sky in the bustle of arrows looked as if rain was drizzling through a hundred small sieves! (Song of the Crusade against the Albigenses. Lessa 207. Translation from Old Occitan by I. Belavin)

This region includes all of the old kingdom of France south of the Loire River and most of what is now known as the Midi-Pyrenees, the largest region of France, covering an area larger than some European countries such as Denmark, Switzerland or the Netherlands. The area in question included the huge Duchy of Aquitaine, the smaller Duchy of Gascony, and many small baronies and marquisates. By the middle of the 11th century, it had formed its own special culture, its own language (Occitan) and its own military traditions.

Miniature "David and Goliath" from the "Stephen Harding Bible", ca. 1109-1111. (Library of the Municipality of Dijon)

In the mid-12th century, almost the entire region, with the exception of the county of Toulouse, came under the control of the county of Anjou. Henry, Count of Anjou became King Henry II of England, with the result that much of this territory soon became part of the vast Angevin Empire (a term used by some historians, but not actually called that), stretching from Scotland all the way to the Spanish border. It is clear that the French monarchy felt simply obliged to destroy this state within a state, although most of it, in feudal legal terms, was theoretically subordinate to the French crown. Between 1180 and the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War in 1337, the kings of France managed to reduce the territory of southern France, which was controlled by the English monarchs, to the southern part of the county of Saintonge, part of the Duchy of Aquitaine, with which it became a possession of England in 1154, and western Gascony.

Bas-relief depicting fighting horsemen (Church of St. Martin, Vomecourt-sur-Madon, canton of Charme, arrondissement of Epinal, Vosges, Grand Est, France)

Again, it should be remembered that it was the south of France, and above all the county of Toulouse, that for a long time was a stronghold of the Albigensians, which led to the Crusade (1209 - 1229), which essentially represented a war of the culturally backward North against the more developed South. The result was the interpenetration of cultures: for example, the creativity of the troubadours penetrated into the northern regions of France, but in the south there was a significant increase in the military influence of the North.

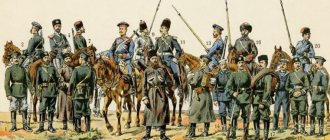

Milites of Northern France. Rice. Angus McBride.

Further, we can say that France was not very lucky in the Middle Ages, because whoever attacked it at that time. Let's start with the 8th century and... there are not enough fingers to count everyone who invaded its territory. In 732, the Arabs invaded France and reached Tours. In 843, according to the Treaty of Verdun, the Frankish state was divided into parts: Middle, Eastern and Western. Paris became the capital of the West Frankish Kingdom, and already in 845 it was besieged and then plundered by the Vikings. In 885-886 they besieged it again. True, this time they managed to defend Paris. However, although the Vikings left, they did so only after they were paid 700 livres of silver or... 280 kg! In 911,913,934,954 the central regions were subjected to crushing raids by the Hungarians. They invaded the south of France in 924 and 935.

That is, the former Carolingian empire was threatened by the Vikings from the north, the Magyars from the east and the Arabs from the south! That is, the French kingdom until 1050 actually had to develop in a ring of enemies, not to mention internal wars caused by such a phenomenon as feudal fragmentation.

Only the knight's cavalry could repel all these blows. And it appeared in France, which is confirmed by the well-known “Bayeux embroidery”, and numerous miniatures from manuscripts, and, of course, effigies, of which there were no less, if not more, in France than in neighboring England. But it has already been said here that many of them suffered during the Great French Revolution. Nevertheless, what has somehow survived to this day is quite enough to restore the entire course of the changes that the equestrian weapons of the knights of France have undergone over “our” three centuries.

Let's start by noting: that in the miniatures of both 1066 and 1100 - 1111, that is, about half a century later, the warriors are depicted almost identically. For example, Goliath from the Harding Bible and the warriors on the bas-relief in the Church of St. Martin in the village of Vomecourt-sur-Madon in the Vosges are very similar to each other. The warriors on the bas-relief are practically no different from those depicted in the “Bayeux embroidery”. They have similar helmets and almond-shaped shields. By the way, they are no different from the traditional images of the knights of Rus', who have exactly the same helmets and almond-shaped or “snake-shaped” (as they are usually called in English-language historiography) shields!

Warrior from the capital letter of the French manuscript "Commentaries on the Psalms" 1150-1200. (Library of the University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France)

However, already in 1150 - 1200. French warriors were dressed in chain mail from head to toe, that is, in a chain mail hauberg with woven chain mail gloves, although at first the chain mail sleeves only reached the elbow. The Bayeux Tapestry shows members of the nobility wearing chainmail stripes on their legs, tied at the back with laces or straps. The majority of warriors do not have this leg protection. But now almost all the warriors in the miniatures are shown dressed in shossa woven from chain mail. They already wear a surcoat over their chain mail. Over the course of 100 years, the teardrop-shaped shield turned into a triangular one with a flat top.

Crusader from the Illustrated Bible, a manuscript from 1190-1200. (Royal National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague). Noteworthy is the outdated leg protection by this time, which can be seen in the “Bayeux embroidery”.

The helmets also changed their shape. Helmets appeared in the form of a dome with a nosepiece, and for helmets with a point on the top of the head, it began to be curved forward. True, turning to the drawings of the “Winchester Bible” (1165-1170), we will notice that, although the length of the chain mail remained the same as in 1066, the figure of the knight visually changed greatly, since the fashion arose to wear them over long caftans with floors up to ankles, and in bright colors too! That is, progress in armament certainly took place, but it was very slow.

Warriors of France in the first half of the 12th century. Rice. Angus McBride.

Chain mail made by the Penza master A. Davydov based on fragments of chain mail found at the Zolotarevsky settlement, that is, dating back to 1236. Exactly 23,300 rings were used to make it. External diameter - 12.5 mm, internal - 8.5 mm, ring thickness - 1.2 mm. The weight of the chain mail is 9.6 kg. All rings are connected by riveting.

A duel between knights. Fresco, ca. 1232-1266. (Ferrande Tower, Pernes-les-Fontaines, France). Here, as we see, there are already horse blankets and, most importantly, forged knee pads. Well, and of course, it is very well shown that a spear blow to the neck, even if protected by chain mail, was irresistible.

French knights of the Albigensian Wars and the leader of the northern crusaders, Simon de Montfort, killed with a stone thrower during the siege of Toulouse. Rice. Angus McBride. The painted helmets (the paint was applied to protect them from rust), the quilted underarmor clothing and the same knee pads are striking.

Beginning of the 13th century was marked by a number of significant improvements in knightly armor. So, the shields became even smaller, chain mail now covered the warrior’s entire body, but to protect the knees they began to use quilted “pipes” with a convex forged “cup”. Although, again, not everyone wears them at first. But gradually the new product comes into widespread use.

Carcassonne effigia. General form.

In the castle of Carcassonne there is an unnamed effigy of the 13th century, brought there from the nearby Abbey of La Grasse and which, despite the damage caused to it, very clearly demonstrates to us the most typical changes in the armament of the knights of this century. On it we see a surcoat, with two coats of arms embroidered on the chest. Moreover, this is not the coat of arms of the Trancavel family. On it is a fortress with one tower and a border. It is known that from the moment Robert I of Anjou “invented” the border in France, it immediately spread throughout Europe, in a wide variety of variations, imitations and imitations, and in Spain it was particularly successful. In France, they began to use it for brizure (modification) of the coat of arms and to include third sons in the coat of arms. That is, this is either the coat of arms of some Spanish knight or a French, but third son, some fairly powerful lord. Finding out this is important for one simple reason. We know the approximate time of death of the owner of the effigy and... we see his armor. He is wearing a chainmail hauberk, but his legs below the knees are covered with anatomical greaves and sabatons made of plates, characteristic of Spain. At that time, only very wealthy people could wear such armor, since they were not widespread. And the effigy itself is very large (see photo), and the larger the sculpture, the naturally... more expensive it is!

Surcoat with coats of arms and a chain mail hood with a characteristic flap. Castle of Carcassonne.

Legs of Carcassonne effigia. The hinges on the wings of the leg armor and the rivets on the plates of the sabatons are clearly visible.

By the way, for some time there was a fashion among knights to depict coats of arms on the chest of a surcoat. David Nicol, in his book The French Army in the Hundred Years' War, cited a photograph of the effigy of the lord of the castle of Bramevac from the first half of the 14th century as an example of obsolete armor that was preserved at that time in remote corners of Southern France. On it we even see three coats of arms at once: a large one on the chest and two coats of arms on the sleeves.

Effigy of Senor Bramevac. One of the tombs of the monastery of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Saint-Bertrand-de-Comenges, Haute-Garonne, France.

An exceptionally valuable illuminated source of information on military affairs of the 13th century is the Macijewski Bible (or “Crusader's Bible”), created by order of the King of France, Louis IX Saint, somewhere in 1240-1250. Its miniatures depict knights and infantrymen, armed precisely in the armor characteristic of this time for France, which belonged to the royal domain. After all, the one who illustrated it simply could not be somewhere away from the king, its customer. And apparently he was very well versed in all the intricacies of military craft. However, in her miniatures there are no horsemen in plate greaves. From this we can conclude that they were already in the South of France, but not yet in the North!

Scene from Maciejewski's Bible (Morgan Library and Museum, New York). The central figure attracts attention. It is difficult to say what biblical story formed the basis of this miniature, but it is significant that he is holding his “grand helmet” in his hand. Apparently he is not very comfortable in it. The wounds depicted in the miniature are typical - a half severed hand, a helmet cut by a blow from a sword, a wound to the face with a dagger.

At the same time, if we look at a number of effigies from the beginning of the 14th century, including the effigies of Robert II the Noble, Count d'Artois (1250 -1302), who fell in the Battle of Courtrai, then it is easy to notice that the greaves on his legs are already are present. That is, at the beginning of the 14th century, they came into use as chivalry everywhere, not only in the South, but also in the North.

Effigy of Robert II the Noble, Count of Artois. (Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris)

Another effigy with plate leg covers and chain mail sabatons. (Corbeil-Essonne Cathedral, Essonne, France)

On the same effigy, chain mail gloves are well preserved. It is obvious that they were woven directly to the sleeves. However, slits were made on the palms to allow them to be removed. It’s just interesting whether they were tightened with some kind of laces or not, because otherwise, in the heat of battle, such a mitten could slip off the hand at the most inopportune moment.

Hands of effigy from the cathedral in Corbeil-Essonne. Close-up photo.

An interesting document has been preserved, which was written shortly before the start of the Hundred Years War and where the process of dressing a French knight in armor was consistently described. So, first the knight should have put on a loose shirt and... combed his hair.

Then came the turn of stockings and leather shoes. Then one should put on legguards and knee pads made of iron or “boiled leather”, a quilted aketon jacket and chain mail with a hood. A shell was put on top of it, similar to a poncho made of metal plates sewn onto fabric and a plate collar covering the throat. All this was hidden by a surcoat caftan with a knight's coat of arms embroidered on it. They had to wear gauntlets made from whalebone plates on their hands, and a sword sling over their shoulders. Only after this did he finally put on a heavy helmet or a lighter bascinet with or without a visor. The shield was used quite rarely at that time.

We see the original chapelle helmet made of overlapping strips of metal in the Chronicle of Badouin d'Avesnes, ca. 1275-1299. (Municipal Media Library of Arras, France). Knights were unlikely to wear such ersatz, but for the city militia this helmet was just right.

The armament and armor of the city militia warrior varied greatly in quality. Moreover, since the city magistrate often purchased weapons for the militia, they were often used not even by one, but by several generations of warriors. Weapons were most often purchased, but wooden shields were usually made locally, which was not too difficult. As a rule, crossbowmen had more full armor than archers, since when a castle or city was besieged, they were the ones who engaged in skirmishes with its defenders, who also fired with crossbows. For example, a list of equipment that a crossbowman named Géran Quesnel received from the Clos de Galais arsenal in Rouen in 1340 has been preserved. According to him, Zheran was given a shell, a corset, most likely chain mail, which had to be worn under the shell, bracers and, in addition, a plate collar.

The same arsenal of the Clos de Galais in Rouen produced armor, siege engines, and ships, although the best quality crossbows still came from Toulouse. By the beginning of the Hundred Years' War, this city could produce silk-covered and lined gambesons, plate armor for warriors and their horses, bascinets, capelin helmets with brims, combat gloves and a variety of shields (either white or painted in the colors of the coat of arms of France and decorated with images golden lilies). Daggers, spears, dard darts, Norman axes, known in England as Danish axes, crossbows and crossbow triggers were produced here, as well as large quantities of crossbow bolts, which were placed in batches in metal-lined boxes. By the way, the first mention of testing armor in France was also found in a document from Rouen dating back to 1340.

During the Hundred Years' War, the range of armor that was produced in the Clos de Galais was supplemented by armor samples borrowed from other countries. For example, the production of Genoese armor covered with canvas and bascinets, as well as plate collars, mentioned in a document of 1347, was established here. The chain mail at this time gradually lost its mittens and hood, and its sleeves and hem were constantly shortened until it turned into short haubergon. Early versions of the cuirass, as is now believed, were made from “boiled leather”, and also, judging by some effects, strips of metal overlapping one another. Many armors had a fabric covering, although, for example, a French document from 1337 reports a shell without a fabric covering, but with a leather lining. That is, in knightly usage at that time there were such!

Richard de Jaucourt - effigia 1340 - (Abbey of Saint-Saint-l'Abbe, Côte d'Or, France)

Initially, protective weapons for arms and legs were made from strips of hard leather and metal. Thus, in 1340, bracers made of plates were mentioned in the Clos de Galais. The chin-bevor, which reinforced the chain mail aventail that descended to the shoulders from the bascinet, became widespread in the 1330s, and in 1337 one of the first French mentions of a plate collar dates back to 1337. For some reason, large helmets made in this arsenal were listed among... ship equipment. Well, the first bascinet that was made here was released in 1336, and these could be simple hemispherical helmets-liners (worn along with the “great helmet”) and helmets with a movable visor, which could be removed if necessary. Also, a study of French effigies shows that completely metal sabatons appeared here much earlier than in other European countries, namely by 1340!

Angus McBride's drawing depicts a knight in such equipment.

The issue of knights recognizing each other in battle, apparently, was of great importance even then. And here we clearly see at least two “experiments” in this area. At first, coats of arms were embroidered (or sewn onto clothes), but in the first quarter of the 14th century they began to be depicted on elletes - shoulder plates made of cardboard, “boiled leather” or plywood, covered with colored fabric. Obviously, the rigid base made it possible to better see the coat of arms, and it may have been stained with less blood than if it was embroidered on a surcoat on the chest. Moreover, they could be round, or square, and even in the shape of... a heart!

French knights in a miniature from the manuscript of Ovid's Moralia, 1330 (National Library of France, Paris)

Thus, we can conclude that the southern and central regions of France played an important role in the development of knightly weapons from 1050 to 1350. Many innovations were tested here and put into practice for mass use. However, even during the Hundred Years' War, the French knighthood still wore chain mail, which did not truly protect against arrows from bows and crossbows, only their legs received cover in the form of anatomical greaves and knee pads, but such an improvement did not affect protection in combat at a distance. . It was because of the insufficient protection of their horsemen that the French lost both the Battle of Crecy in 1346 and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356...

References used: 1. Nicolle, D. French medieval armies 1000-1300. L.: Osprey Publishing (Men-at-arms series No. 231), 1991. 2. Verbruggen, JF The Art of Warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages from the Eight Century to 1340. Amsterdam - NY Oxford, 1977. 3. DeVries, K. Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 1996. 4. Curry, A. The Hundred Years' War 1337-1453. Oxford, Osprey Publishing (Essential Histories 19), 2002. 5. Nicolle, D. Crecy, 1346: Triumph of the Black Prince, Osprey Publishing (Campaign no. 71), 2000. 6. Nicolle, D. Poitiers 1356: The Capture of a King, Osprey Publishing (Campaign No. 138), 2004. 7. Nicollet, D. The French Army in the Hundred Years' War / Trans. from English N.A. Fenogenov. M.: LLC Publishing House AST; Astrel Publishing House LLC, 2004.

To be continued…

Bertrand Du Guesclin (1320-1380)

The outstanding military leader of the Hundred Years' War, Bertrand Deguclin, in his childhood bore little resemblance to the future famous knight.

According to the troubadour Cuvelier from Tournai, who compiled Du Guesclin’s biography, Bertrand was “the ugliest child in Rennes and Dinant” - with short legs, too broad shoulders and long arms, an ugly round head and dark “boar” skin.

Deguclin entered the first tournament in 1337, at the age of 17, and later chose a military career - as researcher Jean Favier writes, he made war his craft “as much out of necessity as out of spiritual inclination.”

Bertrand Du Guesclin became most famous for his ability to storm well-fortified castles. His small force, supported by archers and crossbowmen, stormed the walls using ladders. Most castles, which had small garrisons, could not withstand such tactics.

After the death of Du Guesclin during the siege of the city of Chateauneuf-de-Randon, he was given the highest posthumous honor: he was buried in the tomb of the French kings in the Church of Saint-Denis at the feet of Charles V.

Louis the Lazy

The last French monarch of the Carolingian dynasty reigned for just over a year: from March 986 to May 987. Among the people, he gained the reputation of a ruler who preferred to lie in bed and have fun rather than engage in state affairs. French chronicles disagree: some say that he “did not manage to do anything” due to the brevity of his reign, others say that he “did nothing,” with emphasis on the king’s idleness.

In May 987, Louis the Lazy spent his time hunting. Suddenly the monarch fell from his horse. Those close to him arrived and discovered that Louis had a high fever. Soon the king, who was a little over 20 years old, died. It is unlikely that it was due to mortal laziness: there were rumors that the cause of death was the poisoning of Louis by someone close to him.