LiveInternetLiveInternet

Quote from Bakhyt_Svetlana's message

Read in full In your quotation book or community!

UNIFORMS OF GERMAN MOUNTAIN RIFLE UNITS (SKI UNITS) EDELWEISS

Hats

The headgear worn by the German Army's mountain riflemen during World War II was standard for soldiers of all branches of the military. A distinctive feature of the headdresses of mountain riflemen (Schirm-mutze) was the piping of a light green applied color. This edging was used to trim the edge of the bottom and the upper and lower edges of the band of the caps. Uniform caps for hot climates had a chevron of applied light green braid sewn on the front at an upward angle, bordered by a black, white and red cockade. In addition, between the eagle with a swastika on the crown of the cap and the national cockade on the band, a small metal image of an edelweiss without a stem was pinned. On the caps, on the left side of the cap, an image of an edelweiss with a stem was embroidered with white metal thread or pinned from a zinc alloy. One of the headdresses assigned to mountain rangers was the mountain cap (Bergmiitze). In fact, it copied the caps of the Austrian mountain units of the First World War. Mountain caps were made of greenish-gray woolen or knitted fabric (fellgrau) and had a fabric visor and ear flaps, which in cold weather could be lowered and fastened under the chin, covering the ears and the back of the head. The raised lapels were fastened with two small buttons above the visor.

On the front of the mountain cap there is an eagle with a swastika above a cockade. The eagle was embroidered with dull gray rayon thread on a T-shaped green lining. On the raised lapel on the left was a metal image of an elelweiss with a stem. Special white covers were produced for mountain caps, which were used as camouflage in winter.

Mountain caps were very popular among soldiers and officers, and in 1943 similar headdresses called uniform field caps {Einheitsfeldmiitze Model 1943) were given to military personnel of all branches of the military. The uniform caps were almost a complete copy of the mountain caps; they just lengthened the visor a little. Mountain riflemen also began to wear these hats. The soldiers of the mountain rifle units of the SS troops, like the army mountain riflemen, also had distinctive features that adorned their headdresses. Light green piping on caps was not as common as in the Wehrmacht, and was seen only from time to time. Strange and contradictory orders were issued regarding the wearing of piping on the caps of SS troops. At first, colored piping was introduced, but after a short time they were canceled, however, those who managed to receive caps with piping continued to wear them. Officially, all units of the SS troops were given caps with white piping, and therefore the light green applied color of the mountain troops was seen only from time to time. Unlike the mountain rifle units of the Wehrmacht, the SS troops did not wear the image of edelweiss on their caps.

The mountain riflemen of the SS troops also used mountain and uniform field caps of the 1943 model as headdresses. On them, along the front, an image of a skull and crossbones was sewn in dull gray artificial silk, and on the left, on the lapel, was an eagle with a swastika. Also on the left, behind the eagle, an image of an edelweiss was embroidered on the lapel (in army units the edelweiss badge was metal). The headdresses of the mountain infantry units of the SS troops on the left side were clearly overloaded with emblems. Therefore, caps began to be sewn with one button, instead of the required two, on the front of the flaps. This freed up space, and the eagle was moved forward, placing it above the skull. As a result, only edelweiss remained on the left side of the lapel. Eventually a new, smaller version of the emblem appeared, in which the dull gray eagle and skull were embroidered on a trapezoidal feldgrau background.

In the mountainous parts there were also field caps made of cotton fabric with a camouflage pattern. Early examples were one-sided, but then a second version appeared that could be turned inside out. On one side the cap had a pattern of predominantly green, on the back - brown tones. Special emblems were even designed to be worn on these caps, but judging by front-line photographs, they were used very rarely.

Because many SS soldiers were Muslims of non-German origin. Himmler ordered the wearing of fezzes for these units. SS fezzes were very simple felt headdresses, unlined, edged with a strip of natural or artificial leather and decorated with a black tassel on a cord. For dress uniforms, fezzes were worn in dark burgundy color; for field uniforms, feldgrau colored fezzes were worn. As emblems, standard images of an eagle and a skull, machine embroidery, were sewn on the front of the fez. Most of the uniforms of the mountain riflemen, both army and SS units, were standard for all branches of the military. This applies to field, dress, weekend and other types of uniforms. The distinctive features of the military suit of mountain riflemen are described below.

Army uniform

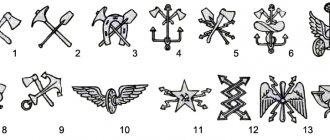

Both officers and lower ranks were entitled to light green flaps under the buttonholes of collars and cuffs in their dress uniform. The shoulder straps of officers had a light green backing, and the shoulder straps of non-commissioned officers and privates were trimmed with the same color piping. The buttonholes on the collar of an officer's uniform and in early versions of soldiers' and non-commissioned officer's uniforms had gaps in a applied color. Ceremonial uniforms were decorated with light green piping along the side, collar, cuffs and folds; often the uniform uniforms were also trimmed with piping along the side and collar. Applied color piping was also sewn on the side seams of dress and dress trousers. The standard bearers received banner baldrics of a standard pattern based on a light green color. The sleeve badge of the mountain troops “Edelweiss” was produced both woven and machine embroidered. The stem was embroidered with green thread, the petals with white thread, and the stamens of the flower with yellow thread. Along the edge of the oval sign, a gray-silver thread depicted a rope intertwined with rings, over which a climbing carabiner and a rock hook were embroidered. Early versions of the sleeve badge had a dark green background, then they began to be issued in feldgrau colors, but the huntsmen preferred to wear the old-style badges. Officers sometimes wore hand-embroidered badges. Examples of sleeve insignia with a brownish background are also known.

The ranger-skiers were assigned not to the mountain rifle units, but to the ranger units. They were given the same light green applied color, but on the left lapel of their field caps, skiers wore a badge in the form of three oak leaves with skis superimposed diagonally on them. The sleeve insignia was a bunch of three oak leaves with brown cuttings, surrounded by an intertwined black-and-white rope. Skis embroidered with silver thread are placed diagonally on top. These badges were embroidered with artificial silk threads. Uniforms of the SS troops

The shoulder straps of non-commissioned officers and privates were edged in light green.

Officer's shoulder straps had a light green lining. The sleeve insignia of the SS mountain units was an oval framed by intertwined silver-gray ropes with woven edelweiss of the same color, but with yellow stamens. Some SS mountain units wore specific buttonholes and cuff bands. Many versions of buttonholes were developed and produced for the SS troops, which never made it into the troops. The most common, judging by the available photographic materials, were the following. 6th SS Mountain Division "Nord"

All German SS divisions were required to wear standard runes on their buttonholes.

The servicemen of the regiments of the Reinhard Heydrich and Michel Geissmayr divisions were entitled to armbands1. The tapes were produced in various versions. They could be machine sewn with silver-gray thread on a black fabric base with a border embroidered with aluminum thread. There were machine-woven ribbons, also black, with letters and a border of aluminum thread. Finally, both the base and the inscriptions on it could be woven from artificial silk. In particular, the cuff bands of the "Michael Geissmayr" regiment are known only of the latter type. They were worn by both officers and lower ranks. 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division "Prince Eugene"

This unit was staffed primarily by Volksdeutsche, and instead of standard runes, its soldiers were required to wear the so-called "Odal rune" on their buttonholes.

Soldiers who came directly from German territories were considered full members of the SS: they were allowed to wear SS runes embroidered with metal thread on their left breast pocket. The cuff bands are known only with the name of the division, but not its regiments. They were produced either sewn or machine-woven from aluminum thread. Ribbons are also known, machine-woven with natural silk thread of very high quality, on a black base, with a characteristic pattern of letters. 13th SS Mountain Division "Hanlschar" (1st Croatian)

As a member of the SS volunteer division.

staffed by non-Germans, the soldiers of this unit were not allowed to use buttonholes with runic images. Instead of runes, on the buttonhole on the right side of the collar there was an image of a hand with a scimitar clutched in it. Under the blade of the scimitar, in the lower left part of the buttonhole, a small image of a swastika was applied. As in the 7th SS Division. German career officers and non-commissioned officers could wear SS runes on their breast pockets. A patch in the form of the Croatian national coat of arms - a heraldic shield with red and white diamonds alternating in a checkerboard pattern - was worn by many soldiers of the division on the fawn sleeve under the image of an eagle. 21st SS Mountain Division "Skanlerberg" (1st Albanian)

Special buttonholes were designed and issued for the Muslim-dominated Albanian Volunteer Division, but they were never used.

The Germans who served in the division wore standard SS runes, and the Albanian volunteers wore “empty” black buttonholes. The division had common cuff ribbons made of natural silk, as well as sleeve patches with the image of a black double-headed Albanian eagle on a red field. 23rd SS Mountain Division "Kama" (2nd Croatian)

Special buttonholes with a stylized image of a sunflower were created and issued for the division, but there is no information about their use.

SS runes were worn only by German military personnel, while Croatian volunteers had black buttonholes without any images. 24th Mountain Infantry (Karstjäger) SS Division

A special version of the buttonholes with the so-called “Karst flower pattern” was designed and apparently issued, but it was never issued to the division’s soldiers. I do not issue cuff bands or any other special patches. Special uniforms for mountain rifle troops In addition to the regular uniform assigned to all units of the Wehrmacht, mountain riflemen widely used variants adapted for cold weather. Some types of such clothing were used only in mountainous parts. Standard winter equipment included an insulated snow suit. It consisted of a heavy, lined jacket equipped with a hood. The jacket was reversible: one side was gray or with a camouflage pattern, the other was white. There were two large pockets sewn on the sides of the jacket, the slits in which made it possible to reach the clothes underneath the jacket. Such jackets were used in pairs with trousers worn over ordinary field trousers. A more specific attire for mountain shooters was the outer windproof jacket. It was made of water-repellent cotton fabric and was intended to be worn over a regular everyday field jacket. The cut of the windproof jacket was double-breasted, non-turning, and made of olive green fabric. The jacket had two large pockets on the flaps and two slanting pockets on the sides, above the waist. The jacket is fastened with a strap on the back. The sleeves also had tabs at the bottom that could be fastened tighter around the wrists in cold weather. On the sleeves of such jackets there were usually stripes with the image of edelweiss, and belt loops were sewn on the belt to support the waist belt of the equipment. In 1942, the anorak blouse was introduced for mountain shooters. which could be worn in a Parsi with windproof “storm” trousers. The anorak was worn over the head, had a sewn hood and a large chest pocket, divided into three parts by vertical seams. At the back of the jacket, in the center, was sewn a fabric flap-“tail”, which could be passed between the legs and fastened in front with buttons. Thus, the jacket turned into a kind of short overalls. At the bottom of the floor, two more pockets were sewn on the sides. The sleeves at the bottom could be pulled together with laces, and the jacket itself could be tightened at the waist with a cord running through the drawstring. The pants that came with the jacket had a high bodice to protect the lower back from the cold. The anorak and windproof trousers were made of feldgrau-colored fabric and provided with a white lining. In winter or on mountain glaciers, the set could be worn with the white side out. Ordinary boots and soldier's boots were used as footwear, but in the mountains the rangers used mountain boots. They had a sole of double thickness, the toe and heel were tacked with ordinary shoe nails, and around the circumference of the sole and heel they were equipped with tricones arranged in pairs. Mountain boots had laces threaded through five pairs of holes, and above that they were laced with hooks. These boots, as a rule, were worn with mountain trousers and windings. Mountain trousers were similar in cut to ordinary uniform field trousers, but had wider legs, tapered at the bottom, to make them easier to tuck under gaiters and into boots. The legs had slits and straps at the bottom. The trousers were further strengthened as they walked. The windings were made from a strip of greenish-gray woolen fabric about 75 cm long and were equipped with a strap and buckle at one end. They were supposed to be wound so that the clasp was on the back of the shin. Brownish-gray gaiters could be worn with standard combat boots. They were fastened with two buckles on the outside of the shin. Data source: Quote from the book: “German mountain rifle and ski units 1939-1945. Author: G. Williamson.”Taken from https://ww2history.ru/4606-jekipirovka-znaki-razlichija-forma-nemeckikh.html

New in blogs

It’s been several months now, and I’ve been collecting bit by bit material on the “Captain Grot’s group” that captured “Shelter 11” and made that famous ascent to Elbrus. The first ascent to this peak in full combat gear. A mini-diorama based on this event is also being slowly built. Not many photographs have survived (I mean the first ascent, and not the second, for propaganda purposes). There is a German newsreel film, “Comrades under the Sign of Edelweiss,” which can be purchased or downloaded online today. In general, I think this story will be interesting to everyone who is not yet familiar with it. I found the “capture” of the fortified hotel “Shelter 11” especially interesting. Pure bluff! On the evening of August 17, 1942, Captain Grot's group approached the Kuban valley east of von Hirschfeld's group to the 3546-meter Hotu-Tau pass at the western foot of Elbrus. Although the Grotto was not hampered by enemy guards, it had to overcome blown-up bridges, steep cliffs and impassable scree. At an altitude of almost 3000 meters under the wild southwestern slope of the Elbrus massif at the edge of the Ullu-Kam glacier, a lead group of 20 people camped. The pack group with weapons, ammunition and food fell behind. It was necessary to wait for her arrival. Before midnight, Grot sent a reconnaissance patrol of eight people under the command of intelligence officer Oberleutnant Schneider with the task of reconnaissance of the situation, location and capacity of shelters in the Elbrus area. Provided with inaccurate maps and completely unaware of local conditions, Captain Grot and his signalman followed Schneider's reconnaissance patrol at 3:00 on August 17 in order to obtain intelligence data as quickly as possible. The remainder of his small force was ordered to wait for the pack column and, as soon as it arrived, to follow him. At sunrise, Captain Grot and his signalman were at the height of the Khotyu-Tau pass (3546 meters). Before them opened a wonderful view of the royal peaks of the Central Caucasus from Ushba and Dykh-tau to Koshtan-tau. In front of them lay the tongues of the Azau, Gara-Bashish, Terskol and Dzhika-Ugon-Kes glaciers, stretching for 17 kilometers from west to east. Grotto couldn’t believe his eyes when, in the middle of this weathered, icy desert crossed by numerous faults, six kilometers away on a rock, 650 meters above, he saw a hotel covered with metal, sparkling in the sun. Schneider's patrol was not visible. At night, he left not a trace on the solid ice of the Azau glacier. Grot was confident that Schneider and his men had captured a building visible from a distance and apparently uninhabited. In a clearly visible place on the trail, he placed a written order for the main group to immediately follow him. In the meantime, the following happened: by morning, Schneider reached this peculiar, airship-like building and promptly discovered that it was occupied by the enemy. Therefore, the patrol went up the glacier to take a position there. Master climber Schwarz from Obersdorf ran down the mountain to warn his fellow Swabian. Grot thought: attack? - Idiocy. To turn back? - It's pointless! In front of Russian machine guns! First, he ordered his faithful signalman, the Munich fireplace cleaner Steiner, to lie down next to Schwartz. Then he took a white handkerchief from his backpack and, waving it, with an air of complete despair, barely alive from fatigue, he walked heavily through the loose snow towards the nearest Russian machine-gun firing point. Grot allowed himself to be captured without resistance. Red Army soldiers, armed with rifles with fixed bayonets, led him to the hotel, where a group of officers stood. The command post was located at the weather station. With an experienced eye, Grot noticed the old, experienced commander of a mountain rifle company. Her full-blooded platoon, consisting of Kyrgyz mountain riflemen, occupied a hotel and exemplary prepared defensive positions. With the help of a sketch drawn in a notebook for reports and the peculiar broken language of the eastern front, which made it possible, if necessary, to establish mutual understanding between people, in cases where it was necessary to overcome the European-Asian language border, who was fighting for his life and the success of the operation, Groth managed to explain to the Russian commander that he is surrounded on all sides. Superior forces are approaching from everywhere, and he, the captain, is sent as a truce, authorized to provide the owners with a free retreat in order to prevent bloodshed. The unthinkable happened: after a long meeting held by civilian meteorologists with their working headquarters, the Russian unit and scientists, seizing weapons, began to descend into the Baksan valley. They left behind four armed, narrow-eyed soldiers. The task was given to them in a whisper, and the captain did not understand it. Fate decreed that all four turned out to be peaceful peasants from the fruit paradise of Osh and Fergana. Grot fed them pies and gave them tea in the kitchen of the weather station. It started a friendship. The rifles were put aside, Steiner and Schwartz were called. Steiner took the imperial war flag from his jacket pocket, Schwartz climbed to the flagpole of the meteorological station and raised the flag on it as a sign of victory. The magnificent stronghold fell into the hands of the Germans without firing a single shot. Schneider's reconnaissance patrol approached, closely following the adventure. During the evening, the people of the advance detachment arrived. By nightfall, all twenty people had gathered and took up defensive positions. The expected night attack never happened. Gemmerler approached with the main detachment. The Elbrus hotel had 150 beds in 40 rooms and, in addition, large supplies of food and property. Having set up the necessary guards the next day, the climbers of the 1st and 4th divisions rested to gain strength for climbing to the top. On August 19 and 20 there was a snowstorm and heavy hail. Despite this, the team undertook a training march to an altitude of 5,000 meters to get used to the thin air. The ascent attempt on August 19 had to be abandoned. On the evening of August 20, a categorical order came over the radio from the commander of the 1st Mountain Rifle Division to conquer the peak of Elbrus in a day. The day of August 21 promised to be favorable, but in the morning it turned out that the forecasts were deceptive. At night, a strong wind howled around the house. At 3:00 the team began the ascent. It started snowing. The glow of the sky in the gray pre-dawn twilight did not bode well. Soon a snowstorm began, there was no visibility. Despite this, the group moved on, six groups of three people each, four of them from the 4th Mountain Division. A small group remained guarded at the Elbrus hotel. An enemy counterattack was still expected. The group of climbers consisted of 20 people: 14 from the 1st Mountain Division and 4 from the 4th Mountain Division, including Captain M. Gammerler and 2 cameramen Wolfgang Gorter and Hanz Ertl. The leader of the group was Captain Heinz Groth.

At 11:00, Chief Sergeant Kümmerle erected a flagpole with the German war flag on the icy peak. Next to it were installed the standards of the 1st Mountain Division with edelweiss and the 4th Mountain Division with gentian. The summit conquerors shook hands. Then followed a careful descent along the same route. Already during the descent from the top, it was noticeable that the military flag had been torn apart by the wind; it seemed that the gods were defending themselves from the invasion of their borders. At the same time (at 11:30), a Soviet mountaineering company formed from Pamiris, commanded by a famous Russian climber, located at an altitude of 5000 meters, because of a snow storm, refused the ordered transition through the Elbrus saddle to the Elbrus hotel. For both the weak hotel garrison and the unarmed ascent group, a possible meeting with a Soviet mountain rifle company would be an unpleasant surprise. In order to reliably secure the eastern flank of the 49th Mountain Rifle Corps in the Elbrus area, the Grot company was reinforced by two battle groups that had been marching towards it since August 15 along the glaciers south of the Elbrus massif. Of course, the enemy did not abandon his attempts to recapture the Elbrus hotel of Shelter 11. Again and again his troops approached it. The best Soviet climbers took part in these operations. Captain Gusev led these unusually difficult operations from a military and mountain point of view. But they suffered setbacks due to the vigilance of the garrison of the Elbrus hotel, whose number by that time had grown to a company. In mid-September the enemy launched an offensive with air support. It was repulsed with heavy losses. The stronghold at the Elbrus hotel turned out to be impregnable if defended correctly. It remained continuously in German hands until the withdrawal of its garrison in early January 1943. Only at the end of winter did Soviet climbers repeat the German ascent on August 21, 1942 to replace the symbols.