Home » Alternative shipbuilding - Fleets that never existed » Cruisers of the Soviet fleet: 1920-1970

Alternative shipbuilding - Fleets that never existedAlternative shipbuilding - Fleets that never existed

admin 08/04/2019 3370

13

in Favoritesin Favoritesfrom Favorites 9

“...Wiping the blood flowing from a cut eyebrow with the back of his hand, political officer Shkrofsky made his way through the narrow, gloomy corridors of the Iron Fist. He realized that the cruiser was doomed - that he himself was doomed if he remained on the sinking ship. But all this no longer mattered to Shkrofsky. His entire being was focused on only one goal: to get to the reserve missile post in the stern and launch the deadly Lezginka towards Great Britain. The projectile aircraft would cope - the political officer was sure of this. And then he, Shkrofsky, will finally be avenged...

...The fire caused by the second British missile reached the cellars of the artillery towers, and in a terrifying flash of smoky flame, the Iron Fist split in half and disappeared into the waves ... "

Novelization of the science fiction film “Iron Fist”, BBC, 1965.

Start:

In 1922, the situation with cruisers in the young fleet of Soviet Russia could not even be called terrible: it was nothing at all. The Soviet fleet simply did not have a single modern turbine cruiser in its composition. The entire cruising force of the Baltic Fleet consisted of five obsolete armored [1] and three armored cruisers [2], a significant part of which were laid down in the last century. Their combat value was, at best, extremely limited.

At other theaters things were even worse. The only cruiser on the Black Sea that survived the intervention and the civil war was the faulty “Memory of Mercury,” forgotten by Wrangel in Sevastopol. On the Arctic Ocean there were the Varyag and Askold returned by the British and, with some stretch, the archaic Peresvet, which claimed the title of armored cruiser. To top it all off, absolutely all the existing cruisers were faulty to one degree or another.

However, there was no choice, and the RKKF had to start in 1922 with what it had.

In 1923-1927, a major overhaul of the armored cruisers Rurik (Profintern) and Bayan was carried out, and the same type Admiral Makarov was partially dismantled to repair the latter. Although both cruisers were outdated, they were nevertheless still quite suitable for auxiliary service. Profintern, reclassified as a 2nd class battleship, was included in the Second Linear Squadron along with two Andrei Pervozvanny class battleships. The repaired “Bayan” was transferred to the Arctic Ocean in 1924 to scare Norwegian poachers[3].

The armored cruisers (excluding the Aurora) were almost all written off and scrapped in 1922-1923. The exception was the cruiser “Bogatyr”.

Preserved as an experimental vessel and floating base, Bogatyr was disarmed in 1927-1928 and subsequently converted into a seaplane carrier. The turrets on the cruiser were dismantled, and instead an above-deck hangar, cranes and a launch catapult purchased in Germany were installed in the aft part. The ship's air group consisted of five flying boats: three more could be stored on the roof of the hangar. Thanks to its relatively high speed (23 knots), the seaplane carrier, called “Red Bogatyr,” could effectively interact with battleships of the “Sevastopol” type, carrying out naval reconnaissance and artillery target designation.

The remaining old ships were designated for scrapping. Unexpectedly, international politics intervened in 1922. In 1923, the Kuomintang government in China, feverishly seeking funds to strengthen its fleet[4], bought the armored cruiser Rossiya and the armored cruiser Askold for $500,000. The USSR, which at that time was not a member of the League of Nations, was not bound by an arms embargo, and the proposed price was still higher than the cost of the ships as scrap metal.

Six light cruisers of the Svetlana class stood in varying degrees of readiness on the stocks of Petrograd and Nikolaev. In 1923, two of them - “Admiral Nakhimov” and “Svetlana”, which were in the highest degree of readiness - it was decided to complete the construction according to the original project, with minor changes caused by the experience of the last world war. Under the designations “Red Crimea” and “Chervona Ukraine”, respectively, these cruisers entered service in 1927-1928.

The Soviet admirals understood very well that completing the construction of ships laid down before the war according to the original design did not solve the problem, but only somewhat mitigated its severity. Compared to the high-speed heavy cruisers with 203-mm artillery that entered service with the leading naval powers in the second half of the 1920s, the completed Svetlanas, with their 30-knot speed and armament of fifteen 130-mm guns, simply looked pathetic. And yet we had to continue to work with them: the difficult economic situation of the USSR and the then dominant doctrine of the “small fleet” made it practically impossible to obtain funds for the laying down of new cruisers.

In 1927, the designers' attention was drawn to the unfinished cruiser Admiral Lazarev.

It was decided to complete this cruiser according to a radically revised design. The engineers took into account the main drawback of the Svetlana-class light cruisers - weak armament - and tried to compensate for it by installing the latest 180-mm BK-1 guns in four single-gun turrets on the new cruiser.

The project was only partially successful. Although the 180-mm 60-caliber cannons had excellent ballistic characteristics, their barrels were heavily overpowered and quickly burned out. And the gun turrets themselves suffered from a lot of shortcomings. As a result, the idea of re-equipping the unfinished Svetlana with 180-mm guns had to be abandoned.

The comparative failure of the “Red Caucasus”, however, did not stop the engineering search. The shipbuilding program of 1929 included the completion of another ship of the Svetlana class - the cruiser Admiral Butakov, which stood at the outfitting wall of the Putilov Plant. Initially, it was also going to be armed with 180-mm guns, but due to doubts that arose, it was decided to review the composition of the weapons.

Renamed “Krasny Ural”, the new cruiser was armed as the main caliber with eight 152-mm 50-caliber guns of the 1908 model, removed from the “Shkval” type monitors. These fairly powerful guns fired at a distance of up to 17,300 meters at a rate of four rounds per minute, and most importantly, they were quite reliable.

It was also possible to take into account a number of other shortcomings of the previous project. Thus, the height of the side in the bow was increased, which improved the seaworthiness of the ship. The auxiliary artillery was positioned more rationally. The new cruiser entered service in 1934.

The fate of two more Svetlanas, Admiral Spiridov and Admiral Greig, remained uncertain for a long time. These ships were stopped at the lowest level of completion, and contractor work on them was only partially completed. In the 1920s, even a plan was considered to convert unfinished cruisers into tankers! With great difficulty, the fleet managed to prove that such a “conversion” simply could not be effective due to the narrow hulls of the ships with small internal volumes.

As a result, in 1929 it was decided to complete the construction of these ships as minelayer cruisers. The armament of the cruisers was reduced to six 130-mm guns, and instead, rails for 180 mines, covered with bulletproof armor, were installed in the aft section below the deck. Another 100 mines could be additionally taken to the upper deck. Immediately before entering service, the cruisers were additionally equipped with eight 76-mm anti-aircraft guns and four anti-aircraft guns (in 1937 they were replaced by eight 100-mm anti-aircraft guns and six 45-mm guns), thereby giving them the ability to serve as air defense ships in the squadron. Under the names “Nachdiv Kotovsky” and “Nachdiv Shchors”, these cruisers entered service in 1933.

Warships. Cruisers. "K" means "very bad"

Were you waiting?

I know, we were waiting. They wrote in the comments. Well, it's time to talk about probably the most useless ships of the light cruiser class of World War II. These are worthy rivals to the Soviet cruisers that remained in ports (with the rarest exception, such as the “Red Caucasus”) throughout the war. Only these ships tried to do something like that, but... To be fair, the K-class light cruisers did everything they could to complete the assigned tasks. Another question is that they could do a little more than nothing.

But - as always, in order.

"Emden"

Here is the cruiser that became the reason for the construction of a new type of ship. Even when it was built, in 1925, it became clear to German naval commanders that the cruiser was “not cake” and was outdated while still on the slipway. The only thing the ship more or less possessed was speed. Everything else needed improvement. Especially weapons and armor.

And while the Emden, by the way, the first large German ship of the post-war period, was being completed, the designers were imprisoned for developing a cruiser that would replace the Emden. Faster, stronger and overall. The main thing is not to go beyond the limit of 6,000 tons, which was in force for Germany under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

It is clear that miracles do not happen, and therefore something will have to be sacrificed.

But the Germans would not be Germans if they had not shown miracles in terms of engineering solutions. It is clear that the only action that would solve all the problems would be to disregard the terms of the Versailles Treaty and build a ship in the absence of tonnage restrictions. However, no one would allow Germany to do this yet (1925 is not 1933), they had to get out as best they could.

And the Germans managed a lot.

Firstly, they “slightly” overestimated the tonnage of the ship. By a little, up to 6,750 metric tons.

Secondly, cruising range was sacrificed. 7,300 miles at a cruising speed of 17 knots - this did not look very significant in comparison with the British light cruisers, which easily had twice the range.

However, German designers were able to offer a very interesting move to increase the cruising range: between the propeller shafts they managed to place two economical diesel engines.

Original, but not very effective. Under diesel engines, the ship developed only 10.5 knots. In addition, the cruiser could run on either diesel engines or boilers. Plus, there was a need for two types of fuel: oil for boilers and diesel fuel for diesel engines. Alas, diesel engines don’t run on heavy oil, and diesel boilers don’t like diesel either.

Therefore, the cruising range under diesel engines with a full refueling of 18,000 miles remains a theoretical parameter. This is if all the containers are filled with solarium. But this is also not a solution, you will agree. Still, it’s a cruiser, not a cargo ship. Moreover, anyone, even a British battleship, could catch up with the ship at such a speed. Refilling with 1200 tons of oil and 150 tons of diesel fuel was considered normal.

Plus, the process of switching from one power plant to another became a big problem. Connecting diesel engines instead of turbines took several minutes, but when it was necessary to make the reverse transition, it was necessary to adjust the propeller shafts relative to the turbines. And accelerating the turbines to operating power took some more time. In general, the use of diesel engines in a combat situation was not only not welcomed, it was excluded.

But we will talk about how convenient and safe it was in the article about Leipzig.

However, in 1926, a contract was signed for the construction of three light cruisers, which were built and when launched received the names Königsberg (April 1929), Karlsruhe (November 1929) and Cologne (January 1930).

The ships turned out to be completely identical in terms of size. Length 174 meters, width 16.8 m, draft at standard displacement - 5.4 m, at full displacement - 6.3 m.

The power plant looked original, but was not impressive. Compared to the light Italian cruisers, everything looked modest. The main installation consisted of six oil boilers and turbo-gear units with a total power of 68,200 hp. and allowed the ship to reach speeds of up to 32 knots.

The auxiliary installation consisted of two MAN 10-cylinder diesel engines with a total power of 1,800 hp. With diesel engines, the cruisers could accelerate to a speed of 10.5 knots.

Reservation.

Here we can draw an analogy with the Italian cruisers “Condotieri” of the first series. That is, there was no armor.

The main belt of the ship was 50 mm thick, plus linings up to 20 mm thick gave 70 mm at best. The deck had a thickness of 20 mm, and there was additional 20 mm armor above the ammunition storage areas.

The turrets had 30 mm armor in the front and 20 mm all around. The conning tower had a thickness in the frontal part of 100 mm, and the side walls were 30 mm.

In general, the reservation could be called anti-fragmentation, nothing more.

The crew of the K-type cruiser in peacetime consisted of 514 people: 21 officers and 493 lower ranks. Naturally, during wartime the number of crew increased and on the Cologne in 1945 it reached 850 people.

Armament.

The main caliber was represented by new 150 mm guns with a barrel length of 65 calibers. The guns fired projectiles weighing 45.5 kg with an initial speed of 960 m/s to a maximum range of 14 nautical miles (26 km), rate of fire - 6-8 rounds per minute.

The guns were placed in three three-gun turrets in a very strange way. Two towers were located in the stern and one in the bow. This was justified by the fact that the cruiser was entrusted with the functions of a light reconnaissance ship, so the battle was supposed to be fought on a retreat.

The aft gun turrets were not installed in a line; to improve forward firing sectors, the first aft turret was slightly shifted to the left side, and the second to the right.

Controversial design. In order to fire forward from the aft turret, the ship had to be turned. And if you take into account that the turret was not turned to the maximum angle, so as not to catch the superstructures, then, in an amicable way, only the bow turret could be used for course shooting.

Not the strongest salvo, you will agree.

The auxiliary artillery was even weaker than that of the Emden. There were at least three 105 mm guns and two 88 mm anti-aircraft guns. On K-type cruisers, to begin with, they generally decided to make do with two 88-mm guns for all occasions.

True, in the 30s a decision was made to strengthen universal artillery. And three twin installations with 88-mm guns were installed on the ships. The first twin 88-mm installation was installed in front of the main caliber turret “B”, the other two were on the platforms to the right and left of the aft superstructure.

In 1934-35, during modernization, the cruisers received 4 twin 37-mm anti-aircraft guns and 8 single 20-mm anti-aircraft guns. And “Cologne” met the end of the war with 10 37 mm automatic guns, 18 20 mm anti-aircraft guns and 4 40 mm Bofors.

Any destroyer could envy its torpedo armament. 4 three-tube torpedo tubes, first with a caliber of 500 mm, and then 533 mm. All cruisers had the ability to take on board 120 mines and the equipment for laying them.

The fire control of the main caliber artillery was carried out using three optical rangefinders with a base of 6 m. But the cruisers became a testing ground for the first German radars. In 1935, a GEMA search radar was installed on the Cologne, operating at a wave length of 50 cm. Experiments with the radar were generally considered successful, but the station itself was not highly reliable in operation, and therefore the radar was dismantled from the ship.

The Seetakt radar was installed on the Koenigsberg in 1938. Once again, the experiment was considered successful, if not for the reliability of the radar. The radar was also dismantled.

The second attempt with Cologne in terms of radar was carried out in 1941. This time they installed the FuMO-21 radar, with which the ship served throughout the war.

In general, the ships turned out to be very strange in terms of power plant and weapons. We’ll talk about the power plant later, but now is the time to talk about the ships’ combat careers.

Combat use.

"Konigsberg"

He received his baptism of fire on September 3-30, 1939 during Operation Westwall, during which Kriegsmarine ships carried out mining of the North Sea.

On November 12–13, 1939, he ensured the mining of the Thames estuary together with the light cruiser Nuremberg.

At the beginning of April 1940, he took part in Operation Weserubung (invasion of Norway) together with the cruiser Cologne.

On April 9, 1940, with 750 troops on board, he successfully landed them in the Bergen area. While retreating, he came under fire from 210-mm Norwegian coastal batteries and received three direct hits. Since the cruiser's armor was not designed to be hit by shells of this caliber, the shells that hit the boiler room caused flooding, extinguished the boilers, and the ship lost power. In addition, the ship's power plant, steering and fire control system failed. Only three shells, albeit large caliber ones.

The command docked the cruiser in the port of Bergen for repairs, where on April 10, 1940, two squadrons of Skew bombers scored three direct hits on the cruiser and three hits close to the side.

As a result, the ship's hull could not stand it, the cruiser took on a large amount of water, and, turning upside down with its keel, sank.

It was picked up in 1942, but never got around to being transported to Germany, and therefore was disposed of by the Norwegians in 1945.

"Karlsruhe"

The combat career of this ship, to put it mildly, did not work out.

Unlike its predecessor with the same name. The cruiser took part in Operation Weserubung, with the goal of capturing the port of Kristiansand. Several hundred paratroopers were placed on board, with whom on April 9, the Karsruhe, despite shelling by Norwegian coastal batteries, broke into Kristiansand harbor and landed troops. The city garrison capitulated.

At 19 o'clock on the same day, the Karlsruhe went to sea, accompanied by three destroyers, heading back to Germany. The ship was sailing at a speed of 21 knots, performing an anti-submarine zigzag. The British submarine Truant attacked the cruiser, firing a salvo of 10 torpedo tubes.

Only one torpedo hit the cruiser, but very successfully, from the British point of view, turning the stern. The crew moved to the escort ships, and the destroyer Greif finished off the cruiser with two torpedoes.

Only one torpedo hit the target, but the damage was so serious that the crew moved to the destroyers Luchs and Seeadler. The commander was the last to leave the ship, after which the destroyer Greif fired two torpedoes at the damaged ship.

"Cologne"

She began her combat service together with the Koenigsberg by laying mines on September 3-30, 1939.

In October-November 1939, she escorted the battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst in the North Sea to the coast of Norway.

In April 1940, he landed troops in Bergen together with the Koenigsberg, but, unlike the sistership, he did not receive damage.

In September 1941, he was transferred to the Baltic in order to prevent the Soviet fleet from leaving for neutral Sweden. Supported the landing operations of German troops on the Moonsund Islands, fired at Soviet positions at Cape Ristna on the island of Hiiumaa.

On August 6, 1942, he was transferred to Norway, to Narvik, to replace the battleship Lützow. Together with the heavy cruisers Admiral Scheer and Admiral Hipper, they formed a detachment that was supposed to attack the northern convoys, but the operations were cancelled.

In 1943, she was transferred to the Baltic, withdrawn from the fleet, and used as a training ship.

He completed his last combat mission in October 1944, laying 90 mines in the Skagerrak Strait.

On March 30, 1945, she was sunk by American aircraft in Wilhelmshaven, sat on the ground, and did not completely submerge.

In April 1945, the main caliber turrets "B" and "C" fired at the advancing British troops for two nights. The shells and electricity were supplied from the shore.

In general, it is impossible to say that the K-class cruisers were useful ships. Practice has shown that these ships cannot be used in the North due to the over-lightened welded hull, the cruisers were also unable to fight off aircraft with such initially modest anti-aircraft weapons, the speed is not very high - it all added up. 100% unsuccessful career.

The only thing that the K-class cruisers were capable of was fulfilling the role of an armed and high-speed landing transport during the operation in Norway. And even then, the loss of two out of three cruisers is not an indicator of success.

In general, the very idea of building such unique ships turned out to be not very good. However, the Germans did not calm down and began work on improving their light cruisers.

Type "E": "Leipzig" and "Nuremberg"

This is a kind of “work on mistakes”, that is, an attempt to somehow improve the characteristics of cruisers, especially in terms of survivability and speed.

These two ships were very different from the K type, on the one hand, and inherited almost all the shortcomings of their predecessors, on the other.

External differences: one chimney instead of two and a more straight stem of the “Atlantic” type. Well, the hulls of the ships have become a little longer, 181 meters versus 174. Standard displacement is 7291 tons, full displacement is 9829 tons, draft at standard displacement is 5.05 m, at full displacement it is 5.59 m.

The main difference was on the inside. A slightly different power plant, a slightly different layout. A third propeller was added, which was turned by two seven-cylinder two-stroke diesel engines from MAN with a total power of 12,600 hp.

The idea was not bad, the main stroke under the turbines was on two propellers, economical on diesel engines on a separate propeller. In theory. In practice, the moment of switching from diesel engines to turbines still deprived the ship of power for some time and made it difficult to control. It turned out that it is very difficult to “pick up” speed on diesel engines with turbines. As a result, very often ships at such a moment were completely unable to move, which ultimately resulted in an emergency.

But overall, this combined setup turned out to be very useful. When in 1939 Leipzig received a British torpedo in the area of the boiler room and the engines stopped (the left one was clear for what reason, and the right one due to a general drop in steam pressure), the urgently started diesel engines made it possible to reach a speed of 15 knots and leave the dangerous area . But the average speed on diesel engines was still about 10 knots. That is not enough.

Well, the epic of history with the combined installation was the incident on the night of October 14-15, 1944. There is a well-known case when the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, returning from near Klaipeda, where it was shelling Soviet troops, rammed the Leipzig, which was heading into the Skagerrak Strait to lay mines. It was at night, in the fog, it’s hard to say why the radar posts of both ships were silent, but the Eugen crashed into the Leipzig at full speed, which... stood, switching the main gearbox from diesel engines to turbines!

As you can see in the photo, the blow hit the Leipzig exactly in the center of the hull between the bow superstructure and the funnel. The bow engine rooms were destroyed, and the cruiser took on 1,600 tons of water. 11 crew members were killed (according to other sources - 27), 6 were missing, 31 were injured. The Eugen's stem was destroyed and several sailors were injured.

The Leipzig was dragged on a cable to Gotenshafen, where the damage was hastily patched up and no further repairs were made. The cruiser was turned into a self-propelled floating battery, since on diesel engines it could still produce its 8-10 knots.

Combat use of the cruiser Leipzig

First use - September 3-30, 1939, Operation Westwall, laying minefields in the North Sea.

On November 7, 1939, Leipzig collided with the training ship Bremse. The damage was of moderate severity, but even then it became clear that the ship’s planid was still the same.

In November-December 1939, he ensured the laying of mines at the mouth of the Humber River, sailed in the retinue of the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and laid mines in the Newcastle area. After laying the mines, he received a torpedo from the British boat Samoun, but reached the base safely.

In September 1943 he was transferred to the Baltic, where he laid mines and fired at Soviet troops. On October 15, 1944, it collided with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and was towed to Gotenhafen (Gdynia) for temporary repairs. In March 1945, he fired at the Soviet troops advancing on Gdynia, having used up the main caliber ammunition, took on board wounded and evacuated civilians and crawled away on diesel engines to Apenrade (Denmark).

9 July 1946 scuttled in the Skagerrak.

"Nuremberg"

“Nuremberg”... It’s not very logical to compare “Nuremberg” with all the previous ones.

In fact, Nuremberg was much larger than all its predecessors, by approximately 10% in size and displacement. Actually, this is not surprising, since Nuremberg was built in 1934, five years later than Leipzig. However, the increase in size and displacement did not affect survivability or any other characteristics at all. Alas. The total length of the Nuremberg is 181.3 m, width is 16.4 m, draft at standard displacement is 4.75 m, at full displacement is 5.79 m. Standard displacement is 7882 and full displacement is 9965 tons.

The power plant was also different from the same Leipzig. The boilers were the same, TZA from Deutsche Werke, but the diesel group consisted of four 7-cylinder M-7 diesel engines from MAN with a power of 3100 hp. Under diesel engines, the cruiser developed a full speed of 16.5 knots.

The armor was disappointingly identical to the K-type armor, without any improvements.

The armament was also absolutely identical to the K-type cruisers, the only difference was that the placement of the turrets was the same as on the K-type cruisers, but the aft turrets were located strictly on the longitudinal axis, without displacement from the center axis.

Auxiliary artillery consisted of the same 88 mm guns in three twin mounts, small-caliber anti-aircraft artillery consisted of 37 mm and 20 mm automatic guns.

Radars. It was more interesting here than on Type K. At the end of 1941, the FuMO-21 radar was installed on the Nuremberg. In 1943 it was replaced by FuMO-22, the antenna of which was mounted on the foremast platform. A fire control radar antenna for 37-mm anti-aircraft guns was mounted in the upper part of the bow superstructure, and FuMB-1 warning system antennas were installed around the perimeter of the superstructure, which warned of irradiation by enemy radars. At the end of 1944, the FuMO-63 air target detection radar was mounted on the cruiser.

Combat career of the cruiser Nuremberg

Beginning of combat career - together with other cruisers during mine laying on September 3-30, 1939.

In November-December 1939, he provided mine laying in the Thames Estuary, in the Newcastle area, and was damaged by a torpedo in the bow from the British submarine Salmon.

From August 1940 to November 1942 he carried out various missions in the Baltic. In November 1942-April 1943 he was in Narvik, in the Tirpitz group. In May 1943 he was transferred back to the Baltic. In January 1945, he set up a minefield in the Skagerrak and was transferred to Copenhagen, where he was captured by the British in May 1945.

On November 5, 1945, according to reparations, it was transferred to representatives of the Soviet Union and renamed the cruiser Admiral Makarov. In 1946 she was commissioned into the Baltic Fleet and was used as a training ship.

In 1959, it was excluded from the lists of the fleet and in 1961 it was cut up for metal.

In general, it is difficult to adequately evaluate the entire project. Construction of Leipzig began before the K-class cruisers entered service. But even then it became clear that the cruisers were very so-so. Why it was necessary to lay down Leipzig and Nuremberg after all is difficult to say. Perhaps just behind-the-scenes games for a budget. Perhaps something else.

By the time the Nuremberg was laid down, all the shortcomings of the K-cruisers had become obvious. And the fact that K-type cruisers could not be used for cruising operations did not raise any doubts at all, either in terms of seaworthiness, or armor, or armament.

The only thing that could justify the mass construction of such controversial ships was that they were better than the Emden, and there was nothing better than them at all.

It would be worth waiting and building something more substantial, for example taking the Admiral Hipper design and just making it smaller.

But the leadership of the fleet (and maybe even higher) did not want to wait, so they built five very controversial ships.

And it is not surprising that all German light cruisers turned out to be unsuitable for use in northern waters due to their frankly weak hull, and their short cruising range did not allow them to send ships on raider operations.

And the ships naturally turned out to be completely unsurvivable in battle. One cannot but agree with this, because three 210-mm shells or one British (not exactly the most powerful) torpedo is not fatal damage. Nevertheless…

It remains only to state that the project of the K-type cruisers contained a huge number of shortcomings and shortcomings. And even with modifications at Leipzig and Nuremberg, it was not possible to get rid of them.

German cruisers lost the most important thing - their survivability, which was the envy of the British in the First World War.

In general, it would be better for Guderian, Wenck and Rommel to use metal to build tanks. Honestly, there would be more benefits. Six light cruisers (including Emden) were unable to have even the slightest impact on the situation at sea, but absorbed so many resources that it is simply impossible not to regret it.

New cruisers of the Soviet fleet

The completion of six old light cruisers of the Svetlana type in 1928-1934 corrected the situation, but only partially. The Soviet navy still lacked fully modern cruisers - and worst of all, Soviet shipbuilding did not have adequate experience building large warships in general. We had to get out of the situation - turn to foreign experience.

In 1932, diplomatic relations between the USSR and France improved so much that it became possible to conclude a Franco-Soviet non-aggression pact. The warming of relations also affected the naval sphere.

On March 11, 1933, the Soviet government asked the naval arsenal in Brest about the possibility of building two heavy cruisers of the “Foch” type for the USSR [5]. The proposal put the French government in a difficult position: despite the significant warming of relations, many conservative politicians of the Third Republic vehemently protested against the supply of weapons to the communists. On the other hand, the French military feared that if they refused, the USSR would simply turn to the Italians, and trust between the nations would be greatly damaged.

As a result, after long negotiations and consultations, a compromise decision was made in 1934 - France built two ships, but supplied them without weapons, which should have been produced and installed in the USSR. The Council of Ministers of the USSR agreed with the proposal (since the capacity of the Soviet shipyards was still not enough) and in the spring of 1934, two cruisers were laid down on the slipway in Brest.

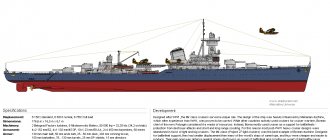

The cruisers laid down in France were a technical variation between the Suffren-class heavy cruisers (which were the official prototype) and the newest heavy cruiser Algerie. They had a total displacement of 13,210 tons and a speed of 32.5 knots.

The armor protection of the cruisers consisted of an 80-mm belt covering the central part of the hull. The belt stretched from the bow to the stern of the main caliber turrets, providing reliable protection against 150 mm guns and acceptable protection against 203 mm guns. A 70-mm horizontal deck rested on top of the belt.

The main armament of the ships (symbolically named “Varlen” and “Dombrovsky”, in honor of the revolutionary leaders of the Paris Commune) were three three-gun turrets with 180 mm 57-caliber B-1-P guns, developed for the new generation of Soviet cruisers. The French were given all the necessary specifications for the manufacture of cellars and barbettes: the installations themselves were manufactured in Russia and installed on the cruisers after their arrival. Auxiliary weapons consisted of six 100-mm B-34-BM universal guns and eight 45-mm 21-K semi-automatic guns.

Both cruisers were launched in 1935 and were officially transferred to the USSR in the fall of 1936. In May 1937, the still unarmed “Dombrovsky” made the transition to the Baltic and stood at the outfitting wall of the Baltic Plant to install artillery. “Varlen” was delayed in France due to complications in Soviet-Italian relations due to the Spanish Civil War, and arrived in the USSR only at the end of 1937.

These ships were the newest and most modern cruisers of the Soviet fleet. The Soviet government actively used them to politically demonstrate the resurgent power of the USSR. “Dombrovsky” made a long voyage across the Atlantic in 1938, visiting the ports of the USA, Mexico, the Pacific Confederation and Chile[6]. The visit of the Soviet cruiser to New York caused great excitement: American naval officers did not miss the opportunity to pay a visit to the ship, carefully studying its main elements.

Finally, in 1935, the USSR began laying down its first own cruisers. Two “medium” cruisers of Project 26 - Kirov and Voroshilov - were laid down in October 1935 for the Baltic and Black Seas, respectively.

These 8,500-ton ships were a combination of Soviet design solutions, Italian technical advice and French experience. They were armed with a standard combination of nine 180 mm guns in three three-gun turrets. The new 180-mm guns were not as heavily modified as the first 60-caliber guns, but still suffered from barrel burnout, which forced constant revision of ballistics.

The initial design of the cruiser provided for a standard displacement of no more than 7,500 tons. But subsequently, under the influence of French experience, it was decided to increase this by 1,500 tons, which made it possible to install more powerful and effective armor, which included an 80-mm armor belt. The speed dropped from the design 37 knots to 35.4 knots, but was still considered more than sufficient.

Two Project 26 cruisers entered service in 1938-1939. In 1936-1937, it was decided to lay down four more ships according to the improved 26-bis project: one each for the Baltic and Black Sea, and two for the Pacific Ocean. These cruisers - Maxim Gorky, Molotov, Kalinin and Kaganovich - entered service in 1940-1942.

Thus, by 1937, the number of built and laid down Soviet cruisers with 180 mm guns amounted to 8 units[7]. The Anglo-Soviet naval agreement of 1937, which recognized these cruisers as “heavy”, stopped the further development of 180-mm cruisers in the USSR. Instead, in 1939, the construction of a huge series of 10,000-ton, formally “light” cruisers of the Chapaev class was planned, but in 1941 these plans were suspended due to the outbreak of war.

In the wake of heavy cruisers

In 1962, there was a high-profile emergency on the cruiser Long Beach.

During training exercises in the presence of high-ranking officials of the state, among whom was President Kennedy himself, the newest nuclear-powered missile cruiser was unable to intercept an air target. Annoyed, Kennedy inquired about the composition of the Long Beach's weapons. Having learned that the cruiser had no artillery at all (there were only 4 missile systems), he, as a former sailor, recommended adding a couple of universal-caliber guns. So, the bold idea to build a ship with purely missile weapons failed. Kennedy was soon killed, and the guided-missile cruiser Long Beach has since carried two 127 mm guns on its deck. Ironically, during its 30 years of service, the cruiser never used its artillery, but regularly fired missiles. And, every time, he hit the target.

On the other side of the ocean, similar processes took place. Immediately after the death of Joseph Stalin, in 1953, the construction of heavy cruisers of Project 82 “Stalingrad” (total displacement - 43 thousand tons) was stopped. The command of the Navy, including the legendary Admiral N.G. Kuznetsov, unequivocally spoke out against these ships: complex, expensive, and, by that time, already obsolete. The estimated cruising range of the Stalingrad did not exceed 5,000 miles at a 15-knot speed. In all other respects, the heavy cruiser was 10-20% inferior to its foreign counterparts; its anti-aircraft weapons raised many questions. Even the excellent 305 mm guns could not save the situation - the naval battle threatened to turn into a second Tsushima.

However, until the mid-1950s, the USSR did not have the real technical capabilities to create a powerful ocean-going nuclear missile fleet and was forced to build ships with conventional artillery and torpedo-mine weapons. In the period from 1949 to 1955, the ship composition of the USSR Navy was replenished with fourteen artillery cruisers of Project 68-bis (Sverdlov class). Initially created for defensive operations in coastal waters, these 14 ships soon turned out to be one of the few effective means of the USSR Navy for delivering paralyzing strikes against aircraft carrier strike groups of a “probable enemy.” At moments of aggravation of the international situation, the cruisers of Project 68-bis were tightly “glued” to the American AUGs, threatening at any moment to bring down hundreds of kilograms of deadly metal from their twelve 152 mm guns onto the decks of aircraft carriers. At the same time, the cruiser itself could not pay attention to the fire of 76 mm and 127 mm guns of American escort cruisers - thick armor reliably protected the crew and mechanisms from such primitive ammunition.

Cruiser "Mikhail Kutuzov" project 68 bis. Displacement 18 thousand tons, maximum speed 35 knots, armament: 12x152 mm main caliber guns, 12x100 mm universal caliber guns, 8 AK-230 anti-aircraft guns. Armored belt - 100mm.

Among naval history buffs, there is an opinion that the construction of three Stalingrad-class heavy cruisers instead of 14 68-bis could significantly enhance the potential of the USSR Navy - the nine 305 mm guns of a heavy cruiser could sink an attack aircraft carrier in a few salvos, and their firing range was times exceeded the firing range of 152 mm guns. Alas, the reality turned out to be more prosaic - the cruising range of Project 68-bis cruisers reached 8,000 nautical miles at an operational and economic speed of 16-18 knots - enough to operate in any area of the World Ocean (as noted earlier, the estimated cruising range of the Stalingrad was almost two times less: 5000 miles at 15 knots). Moreover, time did not allow waiting - it was necessary to saturate the USSR Navy with new ships as quickly as possible. The first 68-bis entered service already in 1952, while the construction of the Stalingrads could only be completed by the end of the 50s.

Of course, in the event of a real combat clash, 14 artillery cruisers also did not guarantee success - while tracking US Navy aircraft carrier groups, a swarm of deck attack aircraft and bombers hovered over the Soviet ships, ready to pounce on their prey from all directions at a signal. From the experience of World War II, it is known that during an air attack on a cruiser similar in design to the 68-bis, from the moment the attack began until the moment when the ship’s masts were hidden in the waves, a time period of 8-15 minutes passed. The cruiser lost its combat capability already in the first seconds of the attack. The air defense capabilities of the 68-bis remained at the same level, and the speed of jet aircraft increased significantly (the rate of climb of the piston Avenger is 4 m/s; the rate of climb of the jet Skyhawk is 40 m/s).

It would seem a completely losing situation. The optimism of the Soviet admirals was based on the fact that a single successful hit could paralyze the AUG - just remember the terrible fire on the deck of an aircraft carrier from an accidentally activated 127 mm NURS. The cruiser and its 1,270 crew will, of course, die the death of the brave, but the AUG will significantly lose its combat effectiveness. Fortunately, all of these theories remain unconfirmed. The 68-bis cruisers appeared on the ocean in a timely manner and served honorably for 40 years in the USSR Navy and the Indonesian Navy. Even when the basis of the USSR Navy was nuclear-powered missile submarines and space-based target designation systems, the old cruisers were still used as command ships, and, if necessary, they could take a battalion of marines onto their decks and support the landing force with fire.

Inglourious scum

During the Cold War, NATO countries adopted an aircraft carrier concept for fleet development, which showed itself brilliantly during World War II. All main tasks, including attacks on surface and ground targets, were assigned to aircraft carriers - carrier-based aircraft could hit targets hundreds of kilometers away from the squadron, which gave sailors exceptional opportunities to control sea space. Ships of other types performed primarily escort functions or were used as anti-submarine weapons.

HMS Vanguard, 1944. One of the best battleships in terms of all its characteristics. Displacement - 50 thousand tons. The main caliber is eight 381 mm guns. Citadel belt - 343...356 mm armor steel

The big guns and thick armor of battleships had no place in the new hierarchy. In 1960, Great Britain scrapped its only battleship, the Vanguard. In the United States, relatively new battleships of the South Dakota class were withdrawn from service in 1962. The only exception was the four Iowa-class battleships, two of which managed to take part in the operation against Iraq. Over the last half century, the Iowas have periodically appeared in the sea only to disappear again after shelling the coasts of Korea, Vietnam or Lebanon, falling asleep for many years of mothballing. Did their creators see such a purpose for their ships?

The nuclear missile era changed all ideas about familiar things. Of the entire Navy, only strategic missile submarines could operate effectively in a global nuclear war. Otherwise, the navy lost its importance and was retrained to perform police functions in local wars. Aircraft carriers did not escape this fate either - over the past half century, they have firmly acquired the image of “aggressors against third world countries”, capable only of fighting the Papuans. In fact, this is a powerful naval weapon, capable of surveying 100 thousand square meters in an hour. kilometers of the ocean surface and strikes many hundreds of kilometers from the side of the ship, was created for a completely different war. But, fortunately, their capabilities remained unclaimed.

The reality turned out to be even more discouraging: while the superpowers were preparing for a global nuclear war, improving the anti-nuclear protection of ships and dismantling the last layers of armor, the number of local conflicts was growing throughout the globe. While strategic submarines hid under the ice of the Arctic, ordinary destroyers, cruisers and aircraft carriers performed their usual functions: they provided “no-fly zones”, carried out a blockade and release of sea communications, provided fire support to ground forces, acted as an arbiter in international disputes, coercing “ disputants" to peace.

The culmination of these events was the Falklands War - Great Britain regained control over the islands lost in the Atlantic, 12 thousand kilometers from its shores. The decrepit, weakened empire showed that no one has the right to challenge it, thereby strengthening its international authority. Despite Britain's nuclear weapons, the conflict took place on the scale of a modern naval battle - with guided-missile destroyers, tactical aircraft, conventional bombs and precision-guided weapons. And the fleet played its key role in this war. Two British aircraft carriers, Hermes and Invincible, especially distinguished themselves. In relation to them, the word “aircraft carriers” must be put in quotation marks - both ships had limited characteristics, a small air group of vertical take-off aircraft and did not carry AWACS aircraft. But even these replicas of real aircraft carriers and two dozen subsonic Sea Harriers became a formidable obstacle to Argentine missile-carrying aircraft, preventing them from completely sinking the Royal Navy.

Atomic killer

In the mid-70s, US Navy specialists began to return to the idea of a heavy cruiser capable of operating off enemy shores without the support of its own aircraft - a real ocean bandit capable of dealing with any possible enemy. This is how the project of the nuclear strike cruiser CSGN (cruiser, strike, guided missle, nuclear-powered) appeared - a large (total displacement of 18,000 tons) ship with powerful missile weapons and (attention!) large-caliber artillery. In addition, it was planned to install the Aegis system on it for the first time in the American fleet.

It was planned to include in the armament complex of the promising CSGN cruiser: - 2 inclined launchers Mk.26 Ammunition - 128 anti-aircraft and anti-submarine missiles. — 2 armored ABL launchers. Ammunition – 8 Tomahawks – 2 Mk.141 launchers Ammunition – 8 Harpoon anti-ship missiles – 203 mm highly automated 8”/55 Mk.71 gun with the awkward name MCLWG. The promising naval gun had a rate of fire of 12 rounds/min, with a maximum firing range of 29 kilometers. Installation weight – 78 tons (including a magazine for 75 rounds). Calculation – 6 people. — 2 helicopters or VTOL aircraft

Of course, nothing like this appeared in reality. The 203 mm gun turned out to be insufficiently effective compared to the 127 mm Mk.45 gun - the accuracy and reliability of the MCLWG turned out to be unsatisfactory, while the light 22-ton Mk.45 had a 2 times higher rate of fire and, in general, there was no need for a new large-caliber artillery system was. The CSGN cruiser was finally destroyed by the nuclear power plant - after several years of operation of the first nuclear cruisers, it became clear that the nuclear power plant, even if we do not consider the price aspect, significantly spoils the characteristics of the cruiser - a sharp increase in displacement, lower combat survivability. Modern gas turbine units easily provide a cruising range of 6-7 thousand miles at an operational and economic speed of 20 knots. - no more is required from warships (under normal conditions for the development of the Navy, ships of the Northern Fleet should not sail to Yokohama, the Pacific Fleet should sail there). Moreover, the autonomy of a cruiser is determined not only by its fuel reserves. Simple truths, they have already been said many times.

Tests of 203 mm Major Caliber Lightweight Gun

In a word, the CSGN project died down, giving way to Ticonderoga-class missile cruisers. Among conspiracy theorists, there is an opinion that CSGN is a CIA special operation designed to direct the USSR Navy along the wrong path of building the Orlans. This is unlikely to be the case, given that all the elements of the supercruiser have one way or another become reality.

Missile dreadnought

In discussions on the Military Review forum, the idea of a highly protected missile and artillery cruiser was repeatedly discussed. Indeed, in the absence of confrontation at sea, such a ship has a number of advantages in local wars. First, the missile dreadnought is an excellent platform for deploying hundreds of cruise missiles. Secondly, everything that is within a radius of 50 km (surface ships, fortifications on the coast) can be swept away by the fire of its 305 mm guns (twelve-inch caliber - the optimal combination of power, rate of fire and weight of the installation). Thirdly, a unique level of security, unattainable for most modern ships (only nuclear attack aircraft carriers can afford 150-200 mm armor).

The most paradoxical thing is that all these weapons (cruise missiles, systems, air defense, powerful artillery, helicopters, armor, radio electronics), according to preliminary calculations, easily fit into the hull of a Queen Elizabeth-class super-dreadnought, laid down exactly 100 years ago - in October 1912!

HMS Warspite - Queen Elizabeth class super-dreadnought, early 20th century

To accommodate 800 vertical launchers of the Mk.41 type, an area of at least 750 square meters is required. m. For comparison: the two aft towers of the Queen Elizabeth main caliber occupy 1100 sq. m. The weight of 800 UVP is comparable to the weight of heavily armored two-gun turrets with 381 mm guns along with their barbettes and armored charging magazines. Instead of sixteen 152 mm medium-caliber guns, 6-8 “Kortik” or “Broadsword” anti-aircraft missile and artillery systems can be installed. The caliber of the bow artillery will be reduced to 305 mm – again a significant saving in displacement. Over the past 100 years, there have been enormous advances in power plants and automation, all of which should entail a reduction in the displacement of the "rocket dreadnought".

Of course, with such metamorphoses, the appearance of the ship, its metacentric height and load items will completely change. To bring the external shape and maintenance of the ship to normal will require long, painstaking work by an entire scientific team. But the main thing is that there is not a single fundamental prohibition against such “modernization”. The only glaring question is what the price of such a ship will be. I offer readers an original plot twist: try to evaluate the “missile dreadnought” of the “Queen Elizabeth - 2012” class in comparison with the missile destroyer of the “Arleigh Burke” class, and we will do it not on the basis of boring exchange rates, but using data from open sources + a drop of common sense logic. The result, I promise, will be very funny.

So, Aegis destroyer of the Arleigh Burke type, subseries IIA. Total displacement – approx. 10,000 tons. Armament: - 96 UVP Mk.41 cells - one 127 mm Mk.45 gun - 2 Phalanx anti-aircraft self-defense systems, 2 Bushmaster automatic cannons (25 mm caliber) - 2 torpedo tubes 324 mm caliber - helipad, hangar on 2 helicopters, magazine for 40 aviation ammunition

The cost of the Arleigh Burke is on average $1.5 billion. This colossal figure is determined by three almost equal components: 500 million – the cost of the steel hull. 500 million – the cost of the power plant, mechanisms and equipment of the ship. 500 million – cost of the Aegis system and weapons.

1. Body. According to preliminary estimates, the weight of the steel structures of the Arleigh Burke hull is in the range of 5.5 - 6 thousand tons. The weight of the hull and armor of the Queen Elizabeth-class battleship is well known - 17 thousand tons. Those. requires three times more metal compared to a small destroyer. From the point of view of banal erudition and incomprehensible eternal truth, the empty box of the Queen Elizabeth hull costs as much as a modern Arleigh Burke-class destroyer - $1.5 billion. And not a penny less. (In addition, we must take into account the reduction in the cost of building the Arleigh Burke due to large-scale construction, but this calculation does not claim to be mathematically accurate).

2. Power plant, mechanisms and equipment. "Arleigh Burke" is driven by 4 LM2500 gas turbines with a total power of 80 thousand hp. There are also three emergency operation gas turbine units manufactured by Allison. The initial power of the Queen Elizabeth power plant was 75 thousand hp. - this was enough to ensure a speed of 24 knots. Of course, in modern conditions this is an unsatisfactory result - to increase the maximum speed of the ship to 30 knots. a twice as powerful power plant will be required. The Queen Elizabeth initially carried 250 tons of fuel - the British super-dreadnought could crawl 5,000 miles at a speed of 12 knots. On board the destroyer Arleigh Burke there are 1,500 tons of JP-5 kerosene. This is enough to provide a range of 4,500 miles at 20 kts. on the move. It is quite obvious that Queen Elizabeth 2012 will require twice as much fuel to maintain the characteristics of Arleigh Burke, i.e. twice as many tanks, pumps and fuel lines. Also, a multiple increase in the size of the ship, the number of weapons and equipment on board will lead to the crew of the Queen Elizabeth 2012 increasing at least twice as much as the Arleigh Burke. Without further ado, we will increase the initial cost of the power plant, mechanisms and equipment of the missile destroyer exactly twice - the cost of the “stuffing” of the “missile dreadnought” will be $1 billion. Does anyone still have doubts about this?

3. “Aegis” and weapons The most interesting chapter. The cost of the Aegis system, including all the ship's radio-electronic systems, is $250 million. The remaining 250 million is the cost of the destroyer's weapons. As for the Aegis system of Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, they have a modification with limited characteristics, for example, there are only three target illumination radars. For example, there are four of them on the cruiser Ticonderoga.

From a logical point of view, all of the Arleigh Burke's weapons can be divided into two main components: Mk.41 launch cells and other systems (artillery, anti-aircraft self-defense systems, jammers, torpedo tubes, helicopter maintenance equipment). I think it is possible to assume that both components have equal value, i.e. 250 million/2=125 million dollars - in any case, this will have little effect on the final result. So, the cost of 96 launch cells is 125 million dollars. In the case of the “missile dreadnought” Queen Elizabeth - 2012, the number of cells increases 8 times - up to 800 UVP. Accordingly, their value will increase 8 times - up to 1 billion dollars. What are your objections to this?

Main caliber artillery. The five-inch light naval gun Mk.45 weighs 22 tons. The 12-inch Mk.8 naval gun, used on ships during World War II, weighed 55 tons. That is, even without taking into account the technological difficulties and labor intensity of production, this system requires 2.5 times more metal. Queen Elizabeth 2012 requires four of these guns.

Assistive systems. The Arleigh Burke has two Phalanxes and two Bushmasters, and the missile dreadnought has 8 much more complex Kortik missile and artillery systems. The number of SBROC launchers for shooting reflectors has increased two to three times. Aviation equipment will remain the same - 2 helicopters, a hangar and landing pad, a fuel tank and an ammunition store.

I believe it is possible to increase the initial value of this property eight times - from 125 million to 1 billion dollars.

That's probably all. I hope the reader will be able to correctly evaluate this terrible hybrid, Queen Elizabeth -2012, which is a combination of an old British ship and Russian-American weapons systems. The meaning is literally the following, from the point of view of elementary mathematics, the cost of a “missile dreadnought” with 800 air defense missiles, armor and artillery will be at least 4.75 billion dollars, which is comparable to the cost of a nuclear aircraft carrier. At the same time, the “missile dreadnought” will not have even a fraction of the capabilities of an aircraft-carrying ship. This is probably the reason for the refusal to build such a “wunderwaffe” in all countries of the world.

Cruisers of the USSR during the war.

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union had quite significant cruising forces. In service or under construction were eight medium and one light cruiser with 180 mm guns, one light cruiser with 150 mm guns, two obsolete light cruisers with 130 mm guns and two mine cruisers. In addition, two old armored cruisers, the Profintern (renamed the Spanish Republic in 1938) and the Bayan, served as coastal defense ships.

The deployment of cruiser forces was as follows:

- KBF - “Dombrovsky”, “Kirov”, “Maxim Gorky”, “Red Ural” and “Nachdiv Kotovsky”

- Black Sea Fleet – “Varlen”, “Voroshilov”, “Molotov”, “Red Caucasus”, “Chervona Ukraine”, “Red Crimea”, “Nachdiv Shchors”

- Pacific Fleet - in the construction of “Kalinin”, “Kaganovich”.

From the very beginning of the war, the cruisers of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet had heavy combat work. The cruisers intensively disrupted the work of German minelayers who were trying to “lock up” the Gulf of Finland, and provided cover for Soviet minesweepers and minelayers operating against German forces. Additionally, the cruising forces of the Baltic Fleet also regularly provided fire support to Soviet troops and launched strikes along the Finnish coast. “Nachdiv Kotovsky” sank in the fall of 1942 after being hit by two mines.

In April 1943, Goebbels said in one of his speeches that “most of the Soviet fleet in the Baltic has been destroyed by the Luftwaffe, and the remnants are so terrified that even Stalin’s threats cannot force them to go to sea.” This boastful assurance aroused the real rage of Stalin, who ordered an immediate demonstration operation. On May 11, 1943, three cruisers - Dombrovsky, Kirov and Krasny Ural - snuck through previously explored minefields in the Gulf of Finland and made a short raid into the eastern Baltic, sinking the German steamer Austloff. The military significance of the raid was small[8], but in propaganda terms it caused significant enthusiasm among Soviet citizens.

At the beginning of hostilities, the Black Sea Fleet had the largest number of cruisers - seven units - of all three main Soviet fleets. He was the only one who had a “permanent” enemy - on June 21, 1941, at Hitler’s request, a formation of two Italian light cruisers - Alberico da Barbiano and Bartolomeo Colleoni - and six destroyers passed through the straits and relocated to Constanta. Subsequently, this “Imperio squadrone di incrociatori del Mar Nero [9] ” caused a lot of trouble for the fleet.

The Black Sea cruisers had the most intense combat work in 1942-1943. They provided support, fire and transport support for the Kerch-Feodosia landing operation of 1942. In many ways, it was thanks to the support provided by the fleet that Manstein’s offensive on Feodosia on January 18 was thwarted, which allowed the Red Army to hold the front and break the blockade of Sevastopol in the summer of 1942.

In August 1942, the light cruiser Chervona Ukraine was lost in a battle with Italian cruisers. This happened on August 18, when an old ship escorting a group of small transports was discovered by German aerial reconnaissance, which sent a detachment consisting of Alberico da Barbiano, Bartolomeo Colleoni and two destroyers to it.

Although the old light cruiser with 130 mm guns had almost no chance against the two faster Italian light cruisers with 152 mm artillery, Chervona Ukraine bravely entered the battle, trying to buy time for the transports to withdraw. At full speed, the Soviet cruiser rushed towards the Italian detachment, which, trying to stay outside the radius of destruction of Soviet guns, was forced to retreat back. The transports managed to escape, but “Chervona Ukraine” received three hits and practically lost its speed.

From immediate destruction, the old cruiser was saved by the approach to the aid of the “Red Caucasus”. The light cruiser, rushing at maximum speed, fired a salvo from its overpowered 180-millimeter guns at maximum distance, laying behind the Italian cruisers. Believing that they were dealing with a new heavy cruiser of the Kirov class, the Italians considered it best to retreat[10].

The heavily damaged Chervona Ukraine, however, remained afloat. Soon other ships of the Black Sea Fleet came to the rescue, and the old cruiser, barely developing 7 knots, trudged to Sevastopol. But German aircraft, rising from the airfields of Crimea, struck the squadron. Despite the desperate efforts of the escort ships and the pulled-up Soviet fighters, the barely moving Chervona Ukraine received two more hits from 500-kg bombs, completely lost speed, and the commander of the Black Sea Fleet decided to abandon the ship.

In the summer of 1943, after numerous Axis failures, Benito Mussolini realized that he was on the wrong side and began to look for an opportunity to exit the war. In August 1943, after secret negotiations with Roosevelt and Stalin, Mussolini officially resigned and was placed under “house arrest”[11], and Italy made a separate peace with the United Nations. According to the terms of the truce, Italian ships on the Black Sea moved to Novorossiysk, where they were interned. After the start of the German invasion of Italy, both cruisers were requisitioned by the Soviet government and commissioned by the USSR Black Sea Fleet as “Kerch” and “Evpatoria”. Under these names, they took part in the final operations of the war against Romania and Bulgaria.

The largest scale of work ultimately fell on two Pacific cruisers. They were the only ships of this class in the USSR Navy that had freedom of access to the world's oceans. In 1942, the Kalinin and Kaganovich, which had just been introduced into the active forces, were transferred through the Panama Canal to the Northern Fleet (and due to the shortage of anti-aircraft guns in Vladivostok, the ships were temporarily armed with 102-mm British anti-aircraft guns and “assistants”). pomami”).

In the northern fleet, Pacific cruisers mainly acted as guards for convoys. In the winter of 1943, they took part in the Battle of Spitsbergen, where they opposed German light cruisers. In the summer of 1943, during Operation Thorhammer - the German fleet's attack on Iceland and the Faroe Islands - these two cruisers were the only ships under the Soviet flag that took an active part in the battle. Together with other light cruisers, they covered a detachment of British escort aircraft carriers near the Faroe Islands, and later finished off the light cruiser Königsberg, damaged by aircraft, which had lagged behind the retreating German fleet.

In 1944, Kalinin took part in Operation Dragoon (landing in Southern France), supporting the Allied forces with fire.

As part of the Lend-Lease program, the USSR in 1943 received from the United States the light cruiser Milwaukee, Omaha class. This obsolete ship, called “Murmansk,” was used in the Northern Fleet as a training ship and was returned to the United States in 1949. In 1944, the USSR was temporarily loaned the modern light cruiser Houston (in the USSR Navy - Spitsbergen), returned in 1949.

After the surrender of Germany, the USSR began to concentrate a significant naval group on the Pacific Fleet, preparing for war with Japan. By August 1945, this included a battlecruiser, four aircraft carriers and three light cruisers - Kalinin, Kaganovich and Varlen, transferred from the Black Sea. Preparations were also made for the transfer of cruising (and battle) forces from the Baltic, in support of the proposed landing operation against Hokkaido, but Japan capitulated before the transfer could be carried out.

SYMMETRICAL RESPONSE

The Soviet Union, having become involved in an arms race, found itself in the role of eternal catch-up.

The country's leadership adhered to the principles of a symmetrical response, slightly adjusted by a “peace-loving” policy. This meant that every US military innovation received a belated mirror response. Only instead of attack aircraft carriers, we built aircraft carrier cruisers, since an aircraft carrier is a weapon of aggression. The appearance of the nuclear-powered cruiser Long Beach in the US Navy in 1961 prompted the Soviet leadership to order a project for a surface ship with a nuclear power plant, capable of operating in remote areas of the World Ocean as part of a group and independently. The American Long Beach, with a displacement of 17,500 tons, was intended to cover a nuclear aircraft carrier; in fact, it was an escort frigate. In the USSR, the fight against nuclear submarines was in first place, so we created a new class of warships - a large anti-submarine ship (BOD). And they also began to design a BOD with a displacement of 8,000 tons with a nuclear reactor from a nuclear submarine. It should be noted that the large mass of nuclear power plants dictates the ship’s displacement - so far it cannot be lower than 8–10 thousand tons.

However, as the design progressed, the power of the reactor increased and the size of the future “foamer of the World Ocean” increased. The Commander-in-Chief of the USSR Navy, Sergei Gorshkov, who really understood the reliability of the then existing nuclear power plants, demanded that the cruiser have a spare power plant running on organic fuel. The result was Project 1144 Orlan, a ship a quarter of a kilometer long (251 m) and displacing 28,000 tons. Almost all naval weapons were assembled on board, except for minesweeping ones: Granit medium-range anti-ship missile systems for combating large surface ships, including aircraft carriers; missile system "Metel"; 12 installations of anti-aircraft missiles "Fort"; 10 torpedo tubes; rocket launcher RBU-600, RBU-1000 and two 100 mm cannons.

But this set changed on each subsequent ship in the series. Which was also a Soviet tradition - no unification, constant modernization. As a result, the four nuclear-powered cruisers built turned out to be of four different types, that is, multi-purpose. They could fight enemy submarines, aircraft and surface ships. Although - by and large - they have become a means of deterrence, which is intended more to demonstrate potential than for a real war.

After the war:

Immediately after the war, the old cruisers of the Soviet fleet were put into reserve. “Red Caucasus”, disarmed[12], was shot in 1952 while testing anti-ship cruise missiles. A more interesting fate awaited the “Red Ural” - in 1951, this old cruiser was transferred to communist China, where, renamed “Shènglì de qízhì”, it served until the 1980s as first a flagship and then a training ship.

Eight cruisers armed with 180-mm guns remained in the Soviet fleet. The war that ended showed that the bet on this artillery was not very successful: the guns suffered from constant barrel burnout. In 1950, the fleet was replenished with five Chapaev-class cruisers (project 68-k), laid down before the war. Counting the three captured cruisers - “Kerch”, “Evpatoria” and “Admiral Makarov” (formerly “Nuremberg”) - the Soviet fleet in the early 1950s had sixteen modern cruisers, which put it in fourth place in the world.

In 1949-1953, the USSR began implementing its last large-scale program for the construction of heavy artillery ships. The post-war shipbuilding program adopted in 1950 provided for the construction of a huge series of twenty-five (!) modern light [13] cruisers of Project 68 bis - the last and most powerful ships of this class in the world.

The implementation of the program was entrusted to seven main shipbuilding enterprises throughout the USSR. The ships were built using all the innovations of modern military shipbuilding - such as sectional assembly of an all-welded hull - as a result of which the average ship construction cycle was 28-36 months. In terms of the totality of their characteristics, these new cruisers successfully surpassed all existing light cruisers of foreign fleets, and were on par with heavy cruisers.

In total, by 1955, 21 Project 68-bis cruisers were laid down. Of these, according to the original project - i.e. as purely artillery light cruisers, only 14 were completed. N.S., who came to power, In 1955, Khrushchev ordered the suspension of work on the last seven cruisers of this type, citing the obsolescence of the very concept of heavy artillery ships. In general, Khrushchev was absolutely right: the rapid progress of atomic and missile weapons (in particular, the beginning of the rearmament of the American fleet with SSM-N-4 “Dingbat” anti-ship missiles in 1953) made purely artillery ships a pointless waste of resources. The ships that were being completed were found a different, more effective use.

German heavy cruisers in battle: Hipper and others

The appearance of new heavy cruisers, built in Germany from the mid-1930s, marked a departure from the “pocket battleship” concept and a return to the 203 mm cruiser design, but at a new level. These ships were built for operations on the open ocean, but circumstances made adjustments to the German plans. “Blücher” died in the first battle, “Admiral Hipper” stood in reserve for half the war, and “Prinz Eugen” ended her career as a gunboat, firing at the advancing Soviet troops...

When creating new heavy cruisers, the Germans returned to a turbine power plant (but with increased steam parameters) and traditional armament of eight 203 mm guns. The armor system was simplified - it now consisted of an inclined 80-mm belt along the citadel, as well as 20-mm upper and 30-mm lower armor decks (the latter had 50-mm bevels to the lower edge of the hull). In addition to the bulges, there were two 20-mm longitudinal bulkheads on each side - between the armored decks at about a third of the ship’s width and under the lower armored deck on the sides of the engine and boiler rooms. In addition, the ships had partially armored ends, which distinguished them favorably from the heavy cruisers of other countries.

"Admiral Hipper"

This ship became the first of two cruisers of the same type. It was laid down in 1935 and formally entered service on April 29, 1939. At the outbreak of World War II, the Hipper was still undergoing testing.

Heavy cruiser "Admiral Hipper", diagram, 1941 Source - S. Patyanin, A. Dashyan, K. Balakin. All cruisers of World War II. M.: Yauza, Eksmo, 2012

The Hipper first opened fire on the enemy on April 8, 1940 at 9:59. The victim of the cruiser was the English destroyer Glowworm, which fell behind its detachment and accidentally found itself in the path of the German Force 2, which was heading to capture Trondheim. The fire distance was 45 kb. Fearing a possible torpedo attack, the Germans kept the enemy at sharp heading angles, so they fired only with the bow turrets. However, the third salvo hit the target: one 203-mm shell hit the target, destroying the radio room of the English destroyer.

During the subsequent battle, the Hipper fired 31 main-caliber shells and 104 universal-caliber shells. Of these, at least one more 203 mm and several 105 mm shells hit the Glowworm, but the destroyer stubbornly continued the battle. He fired all the torpedoes (none of them hit the target, since the Hipper did not expose the side), scored one hit with a 120-mm shell (it penetrated the side of the cruiser’s bow without causing any other damage) and eventually made the legendary ramming attempt . However, this could simply have been a collision, since it was learned from the only British officer rescued from the water that at the end of the battle the steering on the destroyer was no longer working.

The sinking of the destroyer Glowworm. Photo from the bridge of "Admiral Hipper" Source - V. Kofman, M. Knyazev. Hitler's armored pirates. M.: Yauza, Eksmo, 2012

Contrary to existing legends, the Hipper did not receive serious structural damage and did not lose its combat capability, taking on 500 tons of water and receiving a list of 3° to starboard. After the battle, the cruiser continued to participate in the operation to capture Trondheim, where Norwegian coastal batteries offered little resistance and did not hit a single German ship. On the evening of April 12, the Hipper returned to the mouth of the Yade River, where she began dock repairs, which took three weeks. This did not prevent the ship from participating in the second “sea” stage of the Norwegian operation in early June. On the morning of June 9, the fire of 105-mm Hipper guns sank the British armed trawler Juniper (530 tons), firing 97 shells from a “pistol” distance of 10 cabs. On the same day, his victim was the empty military transport Orama (19,840 GRT). In the latter case, 203-mm high-explosive shells with a bottom fuse were used. The target was hit by the third salvo from a distance of 70 kb; in total, the cruiser fired seven salvos, firing 54 main-caliber shells.

The Hipper's first naval battle "on equal terms" was a meeting with convoy WS.5A early in the morning of December 25, 1940, north of the Azores. The Germans noticed that the convoy was guarded by three cruisers at once (one heavy and two light) only after the start of the battle. Moreover, they initially mistook the light cruisers for destroyers, and simply did not notice the aircraft carrier Furious, which was traveling with the convoy. As a result, the commander of the Hipper, Captain Zur See Meisel, decided to use artillery, abandoning the unexpected torpedo attack that promised success.

The fire was opened at 6:39, the Germans fired high-explosive shells at several targets at once and therefore did not hit anywhere. Meisel soon discovered that the enemy significantly outnumbered him, and at 6:50 the Hipper set out on a retreat course, continuing to fire with two turrets at the heavy cruiser Berwick, and with 105-mm guns at the light Bonaventure and Dunedain." It was not until 7:05, when Berwick turned away to bring all her main guns into action, that she received her first hit on the fourth turret. The shell did not explode, but penetrated the 25 mm armor and disabled the turret.

Heavy cruiser Berwick, diagram, late 1941 Source – Jacek Jarosz. Brytyjskie crazowniki ciezkie typu "County". Czesc I. Tarnowskie Gory, 1995

Only after this did the Germans concentrate fire on the largest enemy ship, switching to armor-piercing shells. Firing accuracy immediately improved: at 07:08, the second shell hit the English cruiser in the waterline at the second turret (water began to flow through the hole). The third shell hit the starboard bow 102-mm anti-aircraft gun, ricocheted off the armored deck and exploded in the chimney. Finally, the fourth 203-mm shell hit below the waterline right in the middle of the ship - exactly in the place where the cruiser received a short 114-mm armor belt during modernization. Having come into contact with the belt at an acute angle, the shell exploded on the armor and destroyed thirteen meters of the boule, causing water to flow into the hull. After this, the Hipper turned aside, and at 7:14 the battle stopped.

In total, the German cruiser fired 174 203-mm shells, achieving four hits (2.3% of the total number fired). However, only 38 armor-piercing shells were fired, of which three hit the target (7.7%). In addition, two enemy vehicles were damaged from the fire of 105-mm guns (113 shells were fired). British historian S. Roskill writes that the Berwick received only “minor damage”

, however, other authors report serious damage and flooding. Five people were killed on the British cruiser and several more were wounded. On December 31, Berwick arrived at Gibraltar, where preliminary repairs were carried out, on January 5, she headed to Portsmouth for final repairs, and in May she moved to Rosyth. The repairs, combined with modernization and testing of new equipment, dragged on until October.

The British themselves did not hit the enemy even once in that battle, although the Berwick fired at only one target and at times brought all the towers into action. In general, we can say that in conditions of “regular” combat, when it is possible to correctly distribute targets, and maneuvering does not interfere with shooting, the German fire control system showed a gigantic advantage over the enemy’s fire control system. German radars also worked better - both Berwick and Bonaventure had modern radars, but they only learned about the enemy when he started shooting.

Due to indecision and a frantic change of plans, the German commander missed serious chances for success, which the unexpected torpedo attack promised. Perhaps he shouldn't have come out of a successful fight so quickly. On the other hand, the maximum that he could achieve was to sink or severely damage the Berwick, and Meisel counted on continuing cruising. Indeed, three hours later, the Hipper met and sank the single transport Jumna - this became its only catch during the entire 28-day voyage. The raider “recouped” on the next, February campaign, when during two weeks of operations in the Central Atlantic she sank at least eight transports with a total capacity of 34,000 GRT.

"Admiral Hipper" shortly after entry into service Source - V. Kofman, M. Knyazev. Hitler's armored pirates. M.: Yauza, Eksmo, 2012

Then, for almost two years, the ship did not manage to meet the enemy - until the infamous “New Year’s Battle” of Admiral Kummetz’s detachment (the detachment included the cruisers Hipper and Lützow, as well as six destroyers) with convoy JW-51B on December 31, 1942 of the year. After discovering the convoy and chaotic maneuvering, at 9:23 the Hipper finally opened fire on the British destroyers, firing 5 salvos over 10 minutes from a distance of about 150 kb, but did not hit anyone. This is partly due to very bad weather conditions: it was snowing, the lenses of the rangefinders and sights were constantly covered with a crust of ice, and shooting often had to be stopped to wipe them. The radar failed from the shock after the first salvo.