The battle at the Korsakov post and the death of the cruiser Novik

Saturday, August 7, 1904... At 6 o’clock “Novik” dropped anchor in the roadstead of the Korsakov post.In September 1853, the expedition of G.I. Nevelsky founded the Ilyinsky post on Southern Sakhalin (later the Korsakov post - named after the Russian hydrograph V.A. Rimsky-Korsakov, currently the city of Korsakov). At the same time, the annexation of Sakhalin to Russia was announced. According to the Russian-Japanese treaty, signed in St. Petersburg on April 25 (May 7), 1875, Sakhalin belonged to Russia, but at the same time the right of the Japanese to fish in the Sea of Okhotsk and along the coast of the island was stipulated, and Japanese ships could enter the Korsakov post without port and trade duties.

Military posts not only contributed to securing Sakhalin for Russia, but also laid the foundation for its economic development. The Korsakov post also expanded, becoming the administrative center of Southern Sakhalin. 40 versts north of it, settlers from the Vladimir province founded the large and prosperous village of Vladimirovka (now the city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk). By the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War, 30 thousand people lived on the island.

The appearance of a military ship on the horizon initially caused panic there, but when they saw St. Andrew's flag, almost the entire population gathered at the pier. As soon as the longboat from the Novik docked, a march began from the local orchestra. Of course, no one in the village expected the Russian cruiser, about which there was no news in Russia for eight days after it left Qingdao “in an unknown direction.”

Lieutenant A.P. Shter and part of the team supervised the loading of coal on the shore. “I cannot describe vividly enough the joyful feeling,” he later recalled, “that gripped me when I went ashore; after a 10-day tedious journey, to find myself on the shore, on my Russian shore, with the consciousness that most of the task has already been completed, with the hope that in a few hours we will be on the way to Vladivostok... - all this filled me with some kind of childish delight! The luxurious nature of Southern Sakhalin further contributed to this mood; the crew apparently experienced the same feelings, because everyone energetically and cheerfully set about the dirty work of loading coal.”

Coal began to be loaded at 9:30 a.m.; it had to be transported to the pier in carts, loaded onto barges, towed to a cruiser, and reloaded. Coal was carried in bags, baskets and, most of all, in buckets, and even those were not enough. All the residents helped the Novikovites - the military crew, the exiles, old men and women worked together with the sailors, of course, and the children came running!..

The head of the Korsakov team, Colonel I. A. Artsishevsky, sent a telegraph report about the arrival of “Novik” to the military governor of Sakhalin, Lieutenant General M. N. Lyapunov, and further down the chain of command. Having reached St. Petersburg, already signed by Admiral E.I. Alekseev, this report was ahead of events: “... this day at 6 am “Novik” arrived at the Korsakov post, having received coal, it is heading to Vladivostok.”

And the chief head of the fleet and maritime department, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, noted with satisfaction on the report form: “Brought to the Highest information. Report tomorrow around 4 o'clock. A.". However, fate decreed otherwise, and the next day Nicholas II could only bitterly attribute: “It’s better not to print this...”

Behind the cloud of coal dust that enveloped the Novik, it was difficult to see what was happening at sea, but the horizon was undoubtedly clear. At about 14:30 the cruiser's radiotelegraph began to receive unintelligible signals - only the enemy could transmit them! Since, using the parking lot, the steam in all but two boilers stopped and the burst pipes were suppressed, it was now necessary to dilute the steam in seven boilers, which had just been repaired. There were still two more barges with coal left to accept, but the cruiser sent a semaphore signal to the shore crew to return urgently! A.P. Shter wrote: “Immediately something broke inside, the consciousness of something hopeless flashed through and the mood changed abruptly from joyful to extremely depressed. I really didn’t want to leave this cozy and cheerful-looking corner to embark on such a dubious undertaking as a fight with an as yet unknown enemy. If Japanese telegrams are heard, then it is clear that there is more than one enemy... How many? And who exactly? All Japanese cruisers, even alone, are stronger than the Novik, and here you can’t even give full speed... Undoubtedly, the denouement was approaching...”

At 16:00, the Novik weighed anchor, heading south, and when smoke appeared on the horizon, it picked up the maximum possible speed - 18-19 knots and rushed into the wide eastern part of Aniva Bay, trying to mislead the enemy and counting on after dark set a return course to the La Perouse Strait. The feeling of a decisive moment affected everyone! The final preparations for the battle were made with concentration, they peered intensely at the enemy, trying to determine who they would have to deal with. And, as they approached, they identified it as a Niitaka-class cruiser.

In fact, it was the same type as the Tsushima (the weight of the broadside was 210 kg versus 88 for the Novik). The cruiser Chitose, guarding the La Perouse Strait in the narrowest part (about 23 miles), met Tsushima in the morning, and the commander of Chitose, Captain 1st Rank Takachi Skeichi, ordered Tsushima, under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Sento Takeo, to inspect the Korsakov post. In silhouette, “Tsushima” was very similar to the cruiser of the Vladivostok detachment “Bogatyr”, and the Japanese hoped that while they were recognized from the Russian cruiser, “Tsushima” would be able to get closer to the faster “Novik” (the true state of the mechanisms of which they, naturally, did not know ), and “Chitose” will remain at the exit from Aniva Bay.

At 17:00 the cruiser “Tsushima” turned to cross the “Novik”, giving a radiogram on the “Chitoz”: “I see the enemy and am attacking him.” After 10 minutes, the distance decreased to 40 kb, and from the Novik the Tsushima superstructures became visible to the naked eye, and even the people on its deck became visible through binoculars. “Novik” opened fire on the starboard side, and splashes of shells landed next to the enemy. The cruiser Tsushima responded - the lights of shots from its port side flashed.

At first, the Japanese shells were flying, but soon they began to land closer. To disrupt the zeroing, “Novik” began to describe a series of different coordinates (a maneuver consisting of two successive turns at the same angle in opposite directions to shift the path line), keeping the enemy within 35-40 kb. But already at 17:20 “Novik” came under cover. One of the enemy shells made a hole in the steering compartment under the armored deck, which began to fill with water. Immediately there was an alarming cry: “There’s a hole in the senior officer’s cabin!”, and then new cries: “There’s a hole in the living deck!.. In the wardroom!..” The emergency team rushed to repair it (as far as possible during the battle) damage. After another 5 minutes, the shell destroyed the commander's and navigational rooms, destroying all the charts and navigational instruments, except for one sextant. Fortunately, there have been no casualties yet. “Novik” even began to get ahead of the enemy, moving on a parallel course...

But this was the last stress on the cruiser’s machines—the water-heating tubes burst in two boilers, and the speed dropped sharply. “Involuntarily, impotent anger began to boil in my chest, rolled up into a ball in my throat and burst out with rude curses,” wrote A.P. Shter, “against whom this anger was, I was not aware of, but I tried to pour it out on the enemy.”

An enemy shell killed the commander of the poop gun, N.D. Anikin, and mortally wounded non-commissioned officer P.I. Shmyrev and sailor M.P. Gubenko. The commander of the gun on the left non-firing side himself ran to replace the dead man and continued to send one shell after another. "Began! - thought Stehr. “Now it will be my turn!” And indeed: “There was an explosion behind me... It felt like a piece of my side had been torn out. The drummer, holding his head, in a crying voice: “Your Honor, your brains are out!” “It’s unlikely that I could stand if my brains were gone!..” This shell demolished the aft bridge and engine fans and, in addition to Lieutenant Stehr, wounded ten more sailors. Having bandaged himself right there on the deck, Stehr continued to control the fire of the stern guns.

The enemy's fire weakened noticeably. But at about 17:35, two shells simultaneously hit below the waterline in the steering and rib compartments. The Novik sank almost a meter deep with its stern, and water above the armored deck poured into the wardroom. And then two more boilers failed, the speed was halved, and it became clear that it would not be possible to escape.

A quarter of an hour later, “Novik” turned to the shore to return to the Korsakov post. To our surprise, the cruiser Tsushima also turned to the right, on a diverging course, and stopped firing! “Novik” continued to fire, now from the left side, until the distance increased to 50 kb. We saw that the departing cruiser, when it turned its stern to the Novik, had a list and, being controlled by machines, it went in zigzags.

“Novik” approached the shore as close as possible so that, if necessary, it would be easier to rescue the crew, and when the steering compartment reported that the steering wheel drive was not working, then, driving the onboard vehicles, at 18:20 it came to the Korsakov roadstead, brought the plaster and started pumping out water...

The enemy ship, having left the affected area, also put on a patch and, being unable to continue the battle, sent a radiogram to the “Chitoz”, which was 4 hours away. He asked about the whereabouts of Novik. And although the latter tried to interfere with the negotiations with his apparatus, Tsushima was still able to report that Novik was heading to the Korsakov post.

When the enemy disappeared over the horizon, “Novik” tried to approach the shore, but in doing so, the attached plaster was torn off. Having anchored 960 m from the shore, they found out that the ship had taken in about 250 tons of water through three underwater holes: two in the steering compartment and one under the senior officer’s cabin. There was another hole near the waterline, and in total the cruiser received about ten hits, and six, wooden and metal whaleboats were destroyed. An inspection showed that one of the holes in the steering compartment could not be repaired on our own - a shell hit the joint between the side and the armored deck, causing long cracks. But the most deplorable thing is that at most six out of twelve boilers remained in working order; “Novik lost its speed in the incessant work, Sivka was pushed down steep hills,” A.P. Shter stated with bitterness.

It turned out that it would not be possible to pump out the water from the compartments overnight - there were no means for this in the village, and their own were out of order. Because of these damages to the Novik, and also foreseeing that the exit from Aniva Bay was blocked by another enemy cruiser, M. F. Schultz decided to scuttle the ship on the shallows.

At about 10 o'clock in the evening, when the personnel and all that could be removed from the useful things were taken from the cruiser on barges requested from the shore, the kingstons were opened. Blowing up the Novik could not have occurred to me at that moment! They hoped later, by requesting the appropriate funds from Vladivostok, to raise the ship sunk in a Russian port, and hoped that Novik would still serve Russia! The sailors could not imagine that a year later, according to the Portsmouth Peace Treaty, the southern part of Sakhalin, where their ship was sunk, would be given to the Japanese...

The sunken cruiser Novik off the coast of Sakhalin

At 11:30 p.m., “Novik” lay on the bottom at a depth of 9 m, listing to starboard up to 30°. The stern disappeared under the water, and pipes, a mast and a significant part of the upper deck remained on the surface...

While waiting for the Chitose, the cruiser Tsushima “looked with all eyes wide open all night, fearing that the Novik would be able to escape again,” the Times newspaper wrote, according to a Japanese officer. The battle with Novik became the first baptism of fire for the Japanese cruiser. “One can imagine,” the Japanese officer concluded his story, “how the gunners tried and how they were proud that they managed to damage the Russian cruiser, which, thanks to its speed and brilliant crew, took such an outstanding part in all the battles starting in January.”

By nightfall, “Chitose” moved towards the Korsakov post. The Novikovites saw the beams of its three searchlights, illuminating the expanse of water towards the shore, all night. When dawn broke, the Chitose saw that the Novik was sunk west of Cape Enduma, and between it and the shore there were boats and a steam boat scurrying around. Having approached, “Chitose” with 45 kb shot at the sunken cruiser for an hour, and then, approaching 13 kb, transferred the fire to the shore, firing about a hundred shells, even shooting at individual people who appeared on the shore, damaging a church, five government buildings and eleven private houses. “The defensive detachment was in position, there were no killed or wounded,” the military governor of Sakhalin, Lieutenant General M.N. Lyapunov, telegraphed to the Tsar on the night of August 8th. On the Novik, two smokestacks were destroyed, the mast was damaged, the stern bridge was broken, and there were many holes from shrapnel in the deck and the surface of the side.

The sunken Novik

Japanese cruisers left Aniva and joined the squadron. On August 9, an imperial rescript was sent to the squadron commander: “The cruisers Chitose and Tsushima in Korsakov Bay destroyed an enemy ship and thereby achieved the goal of a long pursuit. We praise it.” Admiral X. Kamimura replied: “The success of the cruisers Chitose and Tsushima in Korsakovsk is entirely due to the greatness of the Supreme Leader.”

On August 9, at the Korsakov post, the Novikov soldiers who were killed and died from wounds were solemnly buried. On the high shore of Aniva Bay near Cape Enduma rested: Pavel Ilyich Shmyrev, engine quartermaster of the 1st article; originally from the village of Serebryano-Prudovskoye, Venevsky district, Tula province; Dmitry Ivanovich Grishin, driver of the 1st article, the village of Kazanskaya Archada, Archada volost, Penza province; Nikolai Dmitrievich Anikin, senior gunner, village of Kalisikha, Vetluzhsky district, Kostroma province; Moisey Petrovich Gubenko, sailor of the 1st article, Podshoy settlement, Akkerman district, Bessarabia province.

Until the morning of August 9, telegrams arriving in St. Petersburg about the death of Novik were not allowed to go into print. But since information continued to come from both the Reuters agency and the Wolf agency, they decided to officially notify Russia: “On August 7, our fleet lost the dashing and glorious, the fastest of our cruisers, which was the beauty of the Russian fleet and the threat of the Japanese... Wounded lower ranks lightly 14, heavily 2, killed 2, Lieutenant Stehr, who remained at his post all the time, was wounded in the head.”

Source: battleships.spb.ru

Better than others

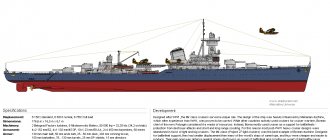

What was revolutionary about Novik compared to other ships of this class? Firstly, a combination of strong artillery and powerful torpedo weapons. It was equipped with four 102-mm cannons. The destroyer also had four two-tube torpedo tubes (later three three-tube tubes) with the ability to launch torpedoes simultaneously. Neither was news in itself, but the combination of such weapons in one hull undoubtedly meant a qualitative leap for the ship.

Anton Zheleznyak Technical and engineering expert

The disadvantages of the Novik's weapons include the poor placement of the artillery, which increased its vulnerability, and the not very high power of the 457 mm torpedoes. But at the time of designing the ship, these shortcomings were not yet obvious.

Control of both torpedo tubes and artillery fire was centralized and even to some extent automated using the latest technology of the time, and the entire firepower of the destroyer could be used very effectively.

Among other things, Novik could lay mines and, thanks to its speed, did it faster and further than other ships. Its qualities allowed for active minelaying: that is, roughly speaking, not just setting up a field in the hope that one day the enemy will stumble upon it... but receiving data from reconnaissance, quickly going out and pouring “balls” right where the enemy is acting right now ( or is about to appear). Then promptly rinse off.

Destroyer "Novik"

Overall: the fastest, capable of effectively defending with artillery, launching torpedo attacks and quickly laying mines. And it's all one ship.

With people's money

The Novik-class destroyers owe their creation to the failures of the Russian fleet in the war with Japan. The colossal losses suffered by the Pacific and Baltic during the battles with Japanese ships had to be replenished, and this had to be done as quickly as possible. The project was financed by the “Special Committee for Strengthening the Military Fleet with Voluntary Donations,” an organization that accumulated donations from Russian citizens in its accounts.

The campaign to collect donations started after the call of Prince Lev Kochubey, who in the very first days of the war appealed to his compatriots through the newspaper “Novoye Vremya”. There were so many people willing to participate in strengthening the Russian fleet that soon, by the highest permission of Emperor Nicholas II, the same “Special Committee for Strengthening the Military Fleet with Voluntary Donations” arose. The funds that came into it were colossal. Although most donors sent small amounts - from a ruble to ten, there were those who donated a million rubles at once, like the Emir of Bukhara, or 300 thousand, like the Kazan Zemstvo or the Senate of Finland, or 200 thousand, like Major General Count Alexander Sheremetyev .

Quite soon, a huge amount of 17 million rubles accumulated in the company’s accounts. The Naval Technical Committee and the Naval General Staff spent a significant part of it - about fifteen million - almost immediately, trying to make up for operational losses. But over two million remained at the disposal of the committee, which, on its own initiative, in December 1905 convened a meeting on the design of new mine cruisers. Although sailors also participated in this meeting, no single decision was made, and the issue remained in limbo for two years.

In 1907, the “Special Committee”, without waiting for instructions from the Naval General Staff, formulated its own requirements for a new high-speed mine cruiser - or, as they began to be called according to the new classification of ships of the same year, a destroyer. A year later, he announced a competition on his own behalf to develop his project. The fact that the Russian fleet needs just such a more modern ship was said by the majority of participants at the meeting two years ago. And as subsequent events showed, the decision made by the committee turned out to be not only completely correct, but also very timely.

The fate of the “newcomers”

Russian sailors immediately appreciated the Novik. The ship was still undergoing testing when the decision was made to build nine destroyers of this project for the Black Sea Fleet. They were slightly different from their prototype, including smaller dimensions and slightly weaker weapons, but fully met the requirements of the theater of operations in which they were to operate. And in total, 53 Novik-class destroyers were laid down for the Russian fleet before the start of the Civil War.

Of these, the sailors received almost four dozen, and several more were completed already in the twenties from the existing reserve. The vast majority of the ships - twenty-five - went to serve in the Black Sea. The Baltic Fleet received eleven. 26 “Novikov” were ordered for it, but many of them could not be completed: the rapid advance of German troops to Revel (present-day Tallinn), where the ships were being assembled, was prevented.

The fate of the “newcomers” turned out to be very different. It reflected, as if in a mirror, the fate of Russian sailors, whom the revolution and the Civil War separated on opposite sides of the front and scattered around the world. The Novik itself, which served in the Baltic, went through the First World War with honor, became part of the Workers 'and Peasants' Red Fleet and received the name Yakov Sverdlov. On the eve of the war, it was modernized and fought until August 28, 1941, when it exposed its side to a German torpedo aimed at the cruiser Kirov. The remaining seven “Noviks” that met the war in the Baltic (many ships of this project were lost during the Civil War) did not fight for too long: they all died during the transition of the Soviet fleet from Tallinn to Kronstadt in August 1941.

Of the more than two dozen “novices” who served in the Black Sea, five met the Great Patriotic War as part of the Soviet fleet. Two of them died, three fought before the Victory, and one - "Zheleznyakov" (in the Russian Imperial Navy - "Corfu") - became Red Banner. Five destroyers in November 1920 left as part of the Russian squadron of the Armed Forces of southern Russia to French Bizerte, from where they never returned to their native shores. And most of the ships were sunk in April 1918 by decision of the Soviet government, which sought to prevent the Black Sea Fleet from falling into the hands of its opponents.

The longest was the service of the three Baltic “noviki”, which in the first half of the 1930s made the transition to the newly created Northern Fleet. They went through the entire Great Patriotic War in its ranks, and one of them - “Kuibyshev” (as part of the Russian Imperial Navy - “Captain Kern”) - was awarded the Order of the Red Banner in 1943 for his military services. And their last combat mission was participation in the first underwater test of nuclear weapons on Novaya Zemlya on September 21, 1955.