German warship, 1934-45.

| Admiral Scheer in Gibraltar in 1936 | |

| Story | |

| Nazi Germany | |

| Name: | Admiral Scheer |

| Namesake: | Reinhard Scheer |

| Builder: | Kriegsmarinewerft Wilhelmshaven |

| Posted: | June 25, 1931 |

| Launched: | April 1, 1933 |

| Commissioned: | November 12, 1934 |

| Home port: | Keel |

| Fate: | Sunk by air attack on 9 April 1945, partially broken and buried. |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Deutschland -class cruiser |

| Bias: |

|

| Length: | 186 m (610 ft 3 in) |

| Ray: | 21.34 m (70 ft 0 in) |

| Project: | 7.25 m (23 ft 9 in) |

| Installed power: | 54000 hp (53260 hp, 39720 kW) |

| Movement: |

|

| Speed: | 28.3 kn (52.4 km/h; 32.6 mph) |

| Classify: | 9,100 nmi (16,900 km; 10,500 mi) at 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Addition: |

|

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Weapons: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| By plane: | 2 × Arado Ar 196 seaplanes |

| Aviation facilities: | One catapult |

Admiral Scheer

[ˌAtmiʁaːl ʃeːɐ̯] was

a Deutschland

-class heavy cruiser (often called a pocket battleship) that served with the Kriegsmarine in Nazi Germany during World War II.

The ship was named after Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the German commander at the Battle of Jutland. She was laid down at the Reichsmarinewerft

in Wilhelmshaven in June 1931 and completed by November 1934.

Originally classified by the Reichsmarine as an armored ship ( Panzerschiff

), in February 1940 the Germans reclassified the remaining two ships of the class as heavy cruisers. [A]

The ship was nominally subject to the 10,000 long tons (10,000 t) limit on warship size set by the Treaty of Versailles, although with a full displacement of 15,180 long tons (15,420 t) she greatly exceeded it. Admiral Scheer

and her sisters, armed with six 28 cm (11 in) guns in two triple turrets, were designed to outpace any cruiser fast enough to catch them. Their maximum speed was 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph), so only a handful of ships in the Anglo-French navy could catch them and were powerful enough to sink them. [1]

Admiral Scheer

saw hard service in the German Navy, including a posting to Spain during the Spanish Civil War, where she bombed the port of Almeria. Her first operation during World War II was a commercial raiding operation in the South Atlantic Ocean; she also made a brief foray into the Indian Ocean. During the operation, she sank 113,223 gross register tons (GRT) of Shipping, making her the most successful capital surface raider ship of the war. After her return to Germany, she was sent to northern Norway to prevent delivery to the Soviet Union. She took part in the unsuccessful attack on Convoy PQ 17 and conducted Operation Wunderland, a mission to the Kara Sea. After returning to Germany in late 1942, the ship served as a training ship until late 1944, when she was used to support ground operations against the Soviet Army. In March 1945 she moved to Kiel for repairs, where she was capsized by British bombers during a raid on 9 April 1945 and partially broken; The remainder of the wreckage was buried when the interior of the Kiel shipyard was filled in after the war. [2]

Design[edit]

Main article: Deutschland-class cruiser

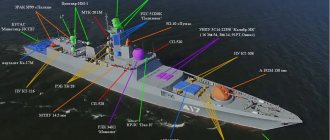

Recognition drawing of Admiral Scheer

Admiral Scheer

was 186 meters (610 ft) long overall and had a beam of 21.34 m (70 ft) and a maximum draft of 7.25 m (23 ft 9 in).

The ship had a design displacement of 13,440 long tons (13,660 t) and a gross displacement of 15,180 long tons (15,420 t), [3] although the ship was officially stated to be within 10,000 long tons (10,160 t). limit of the Treaty of Versailles. [4] Admiral Scheer

was powered by four sets of MAN nine-cylinder, two-stroke, double-acting diesel engines. The maximum speed of the vessel is 28.3 knots (52.4 km/h; 32.6 mph), at 54,000 hp. (53,260 hp, 39,720 kW). At a cruising speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), the ship could travel 9,100 nautical miles (16,900 km; 10,500 mi). According to the draft, its standard composition consisted of 33 officers and 586 enlisted men, although after 1935 this number was significantly increased to 30 officers and 921–1,040 enlisted men. [3]

Admiral Scheer

The primary armament was six 28 cm (11 in) SK C/28 guns mounted in two triple gun turrets, one forward and one aft of the superstructure. The ship carried a battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK C/28 guns in single turrets grouped amidships. Her anti-aircraft battery originally consisted of three 8.8 cm (3.5 in) L/45 guns, although these were replaced by six 8.8 cm L/78 guns in 1935. By 1940, the ship's anti-aircraft battery had been significantly enlarged and consisted of six 10.5 cm (4.1 in) C/33 guns, four twin 3.7 cm (1.5 in) C/30 guns and up to twenty eight 2 cm (0.79 in) Flak 30 guns. By 1945, the anti-aircraft battery had again been reorganized and consisted of six 4 cm guns, eight 3.7 cm guns and thirty-three 2 cm guns. [3]

The ship also carried a pair of four-chamber, 53.3 cm (21 in) deck-mounted torpedo tubes located at its stern. The ship was equipped with two Arado Ar 196 seaplanes and one catapult. Admiral Scheer

" with an armored belt was from 60 to 80 mm (2.4 to 3.1 in); her upper deck was 17 mm (0.67 in) thick and her main armored deck was 17 to 45 mm (0.67 to 1.77 in) thick. The main battery turrets had a side thickness of 140 mm (5.5 inches) and a side thickness of 80 mm. [3] The radar initially consisted of the FMG 39 G (gO) kit, although this was replaced by the FMG 40 G (gO) kit and the FuMO 26 system in 1941. [5]

Main caliber

Eight 203 mm guns located in four twin turrets, two each fore and aft. The Germans considered this arrangement the most preferable from all points of view: a sufficient minimum number of shells in one salvo (four), minimal dead angles of fire and equal fire on the bow and stern.

Quite logical. And if you consider that the Germans simply did not have three-gun turrets for 203 mm guns at their disposal, then the old proven scheme was quite normal.

The turrets of the K-class light cruisers were not suitable precisely because the 203-mm guns required greater strength, and the turrets of the Deutschland-class raiders for 283-mm guns were somewhat heavier than we would like. And the cruiser’s three turrets definitely wouldn’t have worked.

Yes, it didn’t look impressive, since 8 barrels versus 9 for the French “Alger” or 10 for the Japanese “Takao” or the American “Pensacola” were not enough. On the other hand, 4 x 2 was a very common scheme among the British and Italians, and nothing happened, they fought.

German guns were aimed horizontally using electric motors and vertically using electro-hydraulic drives. To load the gun, it was necessary to install it at an elevation angle of 3°, which reduced the rate of fire at long distances due to the fact that lowering the barrel to the loading position and then raising it to the desired angle took time.

The practical rate of fire was about four rounds per minute instead of the originally intended six. But the British cruisers had the same problem, so the rate of fire did not exceed the same 5 rounds per minute.

But the SKC/34 gun itself was excellent. This was the latest development from Krupp. The 122-kg projectile flew out of the barrel with an initial speed of 925 m/sec. Among the guns of that time, only the Italian had higher characteristics, which had an initial speed of 940 m/sec with approximately the same projectile weight. However, the accuracy and survivability of the Italian gun left much to be desired.

Krupp engineers managed to find a middle ground. On the one hand, there is a good trajectory and accuracy, on the other, a barrel life of 300 shots.

The Hipper-class heavy cruisers were well equipped with various types of shells. More precisely, there are four types: - armor-piercing projectile Pz.Spr.Gr. L/4.4 mhb with bottom fuze and ballistic tip; — semi-armor-piercing projectile Spr.Gr. L/4.7 mhb, also with bottom fuze and ballistic tip; - high explosive Spr.Gr. L/4.7 mhb without a special ballistic cap, instead of which a fuse with low deceleration was installed in the head part; — lighting projectile L.Gr. L/4.7 mhb also with ballistic tip.

An armor-piercing projectile loaded with 2.3 kg of explosives could penetrate a 200-mm armor plate at a distance of up to 15,500 m, and 120-130-mm side armor, which constituted the protection of most cruisers of other countries, penetrated at almost any real battle distance when fighting on parallel courses.

Normal ammunition consisted of 120 shells of all types per gun, although cruisers could take 140 without any problems, and the entire magazine contained 1308 armor-piercing, semi-armor-piercing and high-explosive shells, as well as 40 lighting ones, included in the ammunition load of only elevated towers.

Service history[edit]

Admiral Scheer

in 1935

Admiral Scheer

was ordered by the Reichsmarine from the Reichsmarinewerft shipyard in Wilhelmshaven.

[3] Naval rearmament was not popular with the Social Democrats and Communists in the German Reichstag, so it was not until 1931 that legislation was passed to build a second Panzerschiff

.

The money for Panzerschiff B

, which was ordered as

Ersatz

Lothringen, was received after the Social Democrats abstained to prevent a political crisis.

[6] Her keel was laid down on June 25, 1931, [7] under construction number 123. [3] Launched on April 1, 1933. At her launch, she was christened by Marianne Besserer, daughter of Admiral Reinhard Scher, the ship's namesake. [8] She was completed just over a year and a half later, on November 12, 1934, the day she was commissioned into the German Navy. [9] The old pre-dreadnought battleship Hesse was decommissioned and her crew transferred to the newly commissioned Panzerschiff

. [8]

Upon commissioning in November 1934, Admiral Scheer

was transferred to the command of

Kapitän zur See

(

KzS

) Wilhelm

Marshal

. [10] The ship spent the rest of 1934 conducting sea trials and training the crew. [11] In 1935, she had a new catapult and landing sail system installed to control her Arado seaplanes in heavy seas. [5] From 1 October 1935 to 26 July 1937, its first officer was Leopold Bürkner, who later became head of foreign intelligence in the Third Reich. [12]By October 1935, the ship was ready for her first major cruise when she visited Madeira from 25–28 October, returning to Kiel on 8 November. The following summer she cruised through the Skagerrak and English Channel into the Irish Sea, before visiting Stockholm on the return voyage. [eleven]

Spanish Civil War[edit]

Admiral Scheer

Her first overseas deployment was in July 1936, when she was sent to Spain to evacuate German civilians caught in the midst of the Spanish Civil War.

From 8 August 1936, she served alongside her sister ship Deutschland on non-intervention patrols off the Republican coast of Spain. [8] Before June 1937, she served four times in the non-intervention patrol. Her official purpose was to control the flow of military equipment into Spain, although she also recorded that Soviet ships were delivering supplies to the Republicans and protecting ships delivering German weapons to Nationalist forces. [13]During a deployment to Spain, Ernst Lindemann served as the ship's first gunner. [14] After Germany

was attacked on 29 May 1937 by Spanish Republican Air Force aircraft off the coast of Ibiza,

Admiral Scheer

was ordered to bombard the Republican-held port of Almeria in response.

[13] On 31 May 1937, the anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, Admiral Scheer,

flying the Imperial war flag, arrived from Almeria at 07:29 and opened fire on the shore batteries, naval installations and ships in the harbour.

On 26 June 1937 she was replaced by her sister ship Admiral Graf Spee, allowing her to return to Wilhelmshaven on 1 July. However, between August and October she returned to the Mediterranean. [8] In September 1936, KzS

Otto

Kiliaks

replaced Marshal as the ship's commander. [10]

World War II[edit]

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Admiral Scheer

with the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper remained at anchor in the Schillig roadstead near Wilhelmshaven.

On 4 September two groups of five Bristol Blenheim bombers attacked the ships. The first group surprised the anti-aircraft gunners aboard Admiral Scheer

, who nevertheless managed to shoot down one of the five Blenheims.

One bomb hit the deck of the ship and did not explode, two exploded in the water near the ship. The remaining bombs also did not explode. [15] A second group of five Blenheims encountered alarmed German defenses, which shot down four of the five bombers. Admiral Scheer

emerged from the attack unharmed.

[16] In November 1939, KzS

Theodor Kranke became the ship's commander. [17]

Admiral Scheer

underwent refitting while her sister ships went on trading operations in the Atlantic.

[18] Admiral Scheer

was modified in the early months of 1940, including the installation of a new rake-equipped clipper.

[17] The heavy command turret was replaced with a lighter design, and she was reclassified as a heavy cruiser. [13] Additional anti-aircraft guns and updated radar equipment were also installed. [17] On 19–20 July, RAF bombers attacked Admiral Scheer

and the battleship Tirpitz, but scored no hits.[19] On July 27, the ship was declared ready for operation. [17]

Atlantic departure[edit]

Admiral Scheer

Admiral Scheer

made his first combat mission in October 1940.

On the night of October 31, he slipped through the Denmark Strait and escaped into the open Atlantic. [20] Her B-Dienst

identified convoy HX 84, en route from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Admiral Scheer

's Arado seaplanes were in the convoy on 5 November 1940 [18] The armed merchant cruiser HMS Jervis Bay, the convoy's only escort, reported a German raider and attempted to prevent it from attacking the convoy, which was ordered to disperse under the cover of a smoke screen.

[20] Admiral Scheer

's first salvo scored hits on

Jervis Bay

, disabling her wireless equipment and steering gear.

The hull's second salvo hit the bridge and killed her commander, Edward Fegen VC. [21] Admiral Scheer

sank

Jervis Bay

in 22 minutes, but the collision delayed the German ship long enough for most of the convoy to escape.

Admiral Scheer

sank only five of the 37 ships in the convoy, although a sixth ship was sunk by the Luftwaffe after the convoy was dispersed. [22] [23]

December 18 Admiral Scheer

collided with

the approximately 8,651 ton (8,790 dwt)

Duquesa The ship sent a distress signal, which the German raider deliberately authorized in order to attract British naval forces to the area. [24] Krancke wanted to lure British warships to the area to divert attention from Admiral Hipper

, who had just emerged from the Denmark Strait. [25] The aircraft carriers HMS Formidable and Hermes, the cruisers Dorsetshire, Neptune and Dragon, and the merchant armed cruising Pretoria Castle gathered to hunt down the German raider, but she eluded the British. [24]

January 18, 1941 Admiral Scheer

the 8,038 ton

Norwegian oil tanker

Sandefjord After the war , Sandefjord

was rebuilt as the British freighter

Cedar Trader

, shown here.

From December 26 to January 7, Admiral Scheer

rendezvoused with the supply ships

Nordmark

and

Eurofeld

, the auxiliary cruiser Thor and the prizes

Duquesa

and

Storstad

.

The raiders transported about 600 prisoners to Storstad

while they refueled from

Nordmark

and

Eurofeld

.

[26] Between 18 and 20 January, Admiral Scheer

captured three Allied merchant ships totaling 18,738 gross register tons (GRT), [27] including the Norwegian oil tanker

Sandefjord

. She spent Christmas 1940 at sea in the mid-Atlantic, several hundred miles from Tristan da Cunha, before raiding the Indian Ocean in February 1941. [28]

February 14 Admiral Scheer

rendezvoused with the auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and supply ship Tannenfels approximately 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) east of Madagascar.

The raiders resupplied Tannenfels

and exchanged information about Allied trade traffic in the area, splitting the company on 17 February.

Admiral Scheer

then sailed to the Seychelles, north of Madagascar, where he discovered two merchant ships carrying their Arado seaplanes.

She took the 6,994 GRT oil tanker British Defender

as a prize and sank the 2,456 GRT Greek-tagged

Grigorios

.

The third ship, Canadian Cruiser

7178 GRT., managed to send a distress signal before

Admiral Scheer

sank her on 21 February.

The next day the raider encountered and sank a fourth ship, the 2,542 ton Dutch steamer GRT

Rantaupandjang

, although she too was able to send a distress signal before she sank. [29]

The British cruiser HMS Glasgow, which was patrolling in the area, received both messages from Admiral Scheer

» victims s.

Glasgow

launched a reconnaissance aircraft which spotted

Admiral Scheer

.

Vice Admiral Ralph Leatham, Commander East India Station, deployed the aircraft carrier Hermes

and the cruisers Capetown, Emerald, Hawkins, Shropshire and the Australian HMAS Canberra to join the hunt.

Krancke turned southeast to evade his pursuers and reached the South Atlantic by 3 March. Meanwhile, the British abandoned the hunt on February 25 when it became clear that Admiral Scheer

had left the area. [29]

Then Admiral Scheer

headed north, breaking through the Denmark Strait on 26–27 March, evading the cruisers Fiji and Nigeria.

On 30 March she arrived in Bergen, Norway, where she spent the day in Grimstadfjord. The destroyer's escort joined the ship for the passage to Kiel, which they reached on 1 April. [30] During the raid, she covered over 46,000 nautical miles (85,000 km) and sank seventeen merchant ships for a total of 113,223 gross. [18] [30] She was the most successful German capital ship trade raider of the entire war. KzS

Wilhelm

Mendsen

in June 1941 .

[10] The loss of the battleship Bismarck in May 1941 and, more importantly, the Royal Navy's destruction of the network of German supply ships in the aftermath of Operation Bismarck

forced

Admiral Scheer

and her sisters

Lützow

attack

the Atlantic

in late 1941 ocean . [32] On 4–8 September, Admiral Scheer

was briefly transferred to Oslo. There, on 5 and 8 September, No. 90 Squadron RAF, equipped with Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, made a pair of unsuccessful attacks on the ship. On 8 September the ship left Oslo and returned to Swinemünde. [33]

Accommodation in Norway [edit]

Admiral Scheer

, photographed from Prinz Eugen on the way to Norway.

21 February 1942 " Admiral Scheer"

, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the destroyers Z4 Richard Beitzen, Z5 Paul Jakobi, Z25, Z7 Hermann Schoemann and Z14 Friedrich Ihn departed for Norway.

After a brief stop in Grimstadfjord, the ships proceeded to Trondheim. On 23 February, the British submarine Trident torpedoed Prinz Eugen

, causing severe damage.

[34] The first operation in Norway in which Admiral Scheer

was Operation Rösselsprung., in July 1942.

On 2 July, the ship sortied as part of an attempt to intercept Arctic convoy PQ-17. [35] Admiral Scheer

and

Lützow

formed one group, and

Tirpitz

and

Admiral Hipper

the other.

En route to the rendezvous point, Lützow

and three destroyers ran aground, forcing the entire group to abandon the operation.

Admiral Scheer

was seconded to join

Tirpitz

and

Admiral Hipper

at Altafjord. [36]The British noticed the Germans withdrawing and ordered the convoy to disperse. Knowing that surprise was lost, the Germans broke off the surface attack and handed over the destruction of PQ-17 to submarines and the Luftwaffe. Twenty-four of the thirty-five transports in the convoy were sunk. [37]

In August 1942, she flew Operation Wonderland, a mission into the Kara Sea to interdict Soviet shipping and attack targets of opportunity. The length of the mission and the distances made it impossible to provide destroyer escort for the operation; three destroyers will accompany Admiral Scheer,

until they reach Novaya Zemlya, after which they return to Norway.

Two submarines - U-251 and U-456 - patrolled the Kara Gate and the Yugorsky Strait. The Germans initially intended to send Admiral Scheer

with her sister ship

Lützow.

, but since the latter had run aground the previous month, she was unavailable for the operation. [38]

Map showing the route taken by Admiral Scheer

during Operation Wunderland

The operational plan called for strict radio silence to ensure surprise. This required Mendsen-Bolken to have complete tactical and operational control of his ship; shore crews will not be able to lead the mission. [38] 16 August Admiral Scheer

and her destroyer escort left Narvik, heading north of Novaya Zemlya.

Entering the Kara Sea, she encountered heavy ice; In addition to searching for merchant ships, the Arado seaplane was used to scout routes through the ice fields. [39] On August 25, it collided with the Soviet icebreaker Sibiryakov. Admiral Scheer

sank the icebreaker, but not before he sent a distress signal.

[40] The German ship then turned south and arrived two days later from the port of Dikson. Admiral Scheer

damaged two ships in port and fired on the port facilities. Mendsen-Bohlken considered landing troops ashore, but firing from Soviet coastal batteries convinced him to abandon this plan. After interrupting the shelling, Mendsen-Bolken decided to return to Narvik. He arrived at port on 30 August without making significant progress. [41]

October 23 Admiral Scheer

,

Tirpitz

and the destroyers

Z4 Richard Beitzen

, Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt, Z23, Z28 and Z29 left Bogen Bay for Trondheim.

There Tirpitz

stopped for repairs, while

Admiral Scheer

and

Z28

continued on their way to Germany.

[42] Fregattenkapitän

Ernst Gruber acted as the ship's commander at the end of November.

[10] In December 1942, Admiral Scheer

returned to Wilhelmshaven for overhaul, where she was attacked and slightly damaged by RAF bombers.

Consequently, Admiral Scheer

moved to the less vulnerable port of Swinemünde.

[35] In February 1943, the ship

was commanded by

KzS

Richard Roth-Roth.

[10] Until the end of 1944, Admiral Scheer

was a member of the fleet training group. [43]

Return to the Baltic [edit]

KzS

Ernst-Ludwig Thienemann, the ship's last commander, took command from

Admiral Scheer

in April 1944.

[10] On 22 November 1944 Admiral Scheer

, the destroyers

Z25

and Z35 and the 2nd Torpedo Boat Flotilla relieved the cruiser

Prinz Eugen

and several destroyers supporting German forces fighting the Soviet Union on the island of Ezel in the Baltic. [44] The Soviet Air Force launched a series of air strikes against German forces, all of which were successfully repulsed by heavy anti-aircraft fire. [45] However, the Arado seaplane was shot down. [43]On the night of November 23–24, the German naval forces completed the evacuation of the island. A total of 4,694 military personnel were evacuated from the island. [45]

Admiral Scheer

capsized in Kiel

At the beginning of February 1945, Admiral Scheer

stationed off Samland with several torpedo boats in support of German forces fighting the Soviet advances.

On February 9, the ships began shelling Soviet positions. Between 18 and 24 February, German forces launched a local counterattack; Admiral Scheer

and torpedo boats provided artillery support, targeting Soviet positions near Pez and Gross-Heidekrug.

The German attack temporarily restored land connections to Königsberg. [46] By March, the ship's guns were badly worn out and needed repairs. On March 8, Admiral Scheer

left the eastern Baltic to move to Kiel; she transported 800 civilian refugees and 200 wounded soldiers. An uncleared minefield prevented her from reaching Kiel, so she unloaded her passengers at Swinemünde. Despite the worn-out gun barrels, the ship then fired on Soviet forces outside Kolberg until the remaining ammunition was expended. [43]

The ship then loaded refugees and left Swinemünde; she successfully navigated minefields en route to Kiel, arriving there on 18 March. By early April, the guns in the aft turret had been replaced at the Deutsche Werke shipyard. During the repair process, most of the crew went ashore. On the night of April 9, 1945, more than 300 RAF aircraft launched a general attack on the harbor at Kiel. [43] Admiral Scheer

was hit by bombs and overturned. After the end of the war, the ship was partially dismantled for scrap, although part of the hull remained in place and was covered with wreckage from the attack when the inner harbors were filled in the post-war era. [47] The number of casualties resulting from her loss is unknown. [9] [48]

Anti-aircraft weapons

The cruisers each had 6 two-gun 105 mm C/31 (LC/31) mounts, which provided fire from 6 barrels in any sector.

The installations of station wagons were also very advanced, if not unique for that time. They had stabilization in three planes; no cruiser in the world had such installations. In addition, if we add to this the possibility of remote control of guns from artillery fire control posts...

There were also disadvantages. First, tower electrification, which did not handle salt water very well. Secondly, the installations were open, and the crews were not protected from above from fragments and everything else.

37-mm automatic cannons of the SKC/30 model were placed in single and twin and also stabilized installations. The presence of gyro stabilization and manual control is a good step forward from Rheinmetall. Yes, the quadruple Vickers and Bofors of the British had a higher density of fire. But German guns were more accurate.

The 20mm anti-aircraft guns were perhaps the only weak link. The Allied Oerlikons were twice as fast-firing as the Rheinmetall, and the German machine gun required 5 crew members versus 2-3 for the Oerlikon.

Footnotes [edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑

The third ship, Admiral Graf Spee, was scuttled after the Battle of the River Plate. See Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 220. - FMG stands for Funkmess Gerät

(radar equipment) and the numerical digits indicate the year of manufacture of the device.

"G" indicated that the equipment was manufactured by GEMA, "g" indicated that it operated in the 335 to 440 MHz band, and "O" indicated the location of the device above the forward rangefinder. FuMO stands for Funkmess-Ortung

(detection radar). See Williamson, p. 7.

Quotes [edit]

- Dad, page 7.

- For the location of the flood, see Dodson, Aidan; Kant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after Two World Wars

. Barnsley: Seaforth. p. 165. ISBN 9781526741981., top. - ^ B s d e e Groners, p. 60.

- Dad, page 3.

- ^ a b Groener, page 61.

- Meier-Welcker et al. , item 435.

- ↑

Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 227. - ^ abcd Williamson, page 24.

- ^ a b Groener, p. 62.

- ^ abcdef Williamson, page 22.

- ^ ab Wheatley, page 69.

- Bürkner, Leopold: Bordgemeinschaft der Emdenfahrer.

- ^ a b c Chupa, page 20.

- Grützner, pp. 91-100.

- Jump up

↑ Watson, p. 71. - ↑

Watson, pp. 71–72. - ^ abcd Watson, page 72.

- ^ abc Williamson, page 33.

- Rover, page 33.

- ^ a b Showell, p. 66.

- Edwards, p. 90.

- Rover, page 48.

- "HX Convoys". Arnold Hague Convoy Database. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ ab Rohwer, page 52.

- Edwards, p. 99.

- Rover, page 53.

- Rover, page 56.

- Williamson, p. 34.

- ^ ab Rohwer, page 59.

- ^ ab Rohwer, page 65.

- Hümmelchen, page 101.

- O'Hara et al., paragraph 71.

- Rover, page 98.

- Rover, page 146.

- ^ ab Williamson, page 35.

- Edwards, p. 194.

- Rover, pp. 175-176.

- ^ ab Zetterling & Tamelander, page 150.

- Zetterling & Tamelander, p. 151.

- Zetterling & Tamelander, pp. 151-152.

- Zetterling & Tamelander, p. 152.

- Rover, page 206.

- ^ abcd Williamson, page 36.

- Rover, pp. 373-374.

- ^ ab Rohwer, page 374.

- Rover, page 387.

- ↑

For the exact location of the crash, see Dodson, Aidan;

Kant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after Two World Wars

. Barnsley: Seaforth. item 165, top image. ISBN 9781526741981. - ↑

Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 228.

Torpedo weapons

In general, on cruisers of that time, torpedoes were considered as some kind of additional weapons, which is why many devices were not installed. On average 6-8, and even those were often filmed. We are not taking Japanese cruisers into consideration here; the Japanese generally had torpedoes as part of their attack doctrine.

Therefore, 12 torpedo tubes on a heavy cruiser was clearly too much, since it is worth noting that the German 533 mm torpedoes are not at all the 610 mm Long Lances of the Japanese. But that's how it was done.

Radar and sonar equipment

Here the German engineers had a blast. Two sonar systems, passive "NHG" - used for navigation purposes. The second system, also passive, “GHG,” was used to detect submarines, although torpedoes fired at the ship were repeatedly detected with its help.

Further. Active system “S”, analogue of the British “Asdic”. A very effective system.

Radars were also installed, albeit not immediately during construction, but in 1940. The first to receive FuMo 22 were “Hipper” and “Blücher”, which were ready at that time; “Blücher” sank with it, and “Hipper” was equipped with two FuMG 40G radars during the modernization of 1941.

Prinz Eugen immediately received two FuMo 27 type locators, and in 1942 also a FuMo 26 on the roof of the main rangefinder post at the top of the bow superstructure. By the end of the war, the cruiser's radar set was generally luxurious: one more, FuMo 25 model, on a special platform behind the mainmast, as well as an old FuMo 23 on the stern control panel. In addition, it had a Fu Mo 81 air surveillance radar on the top of the foremast.

In addition, the cruisers were also equipped with detectors for detecting enemy radar radiation. These detectors bore the names of Indonesian islands. Prinz Eugen had five Sumatra devices on the foremast, and then received the Timor detection system. "Hipper" also had "Timor". Both cruisers were equipped with passive detectors of the FuMV Ant3 “Bali” type.

In general, passive detectors for German ships, which usually found themselves in the role of those being hunted, that is, game, turned out to be very useful. But by the end of the war, they could no longer cope, because the enemy had too many radars with different wavelengths.

Links[edit]

- "Burkner, Leopold". Bordgemeinschaft der Emdenfahrer

. Retrieved October 18, 2013. - Chupa, Heinz (1997). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1939–1945

. Rastatt: Moevig. ISBN 978-3-8118-1409-7. - Edwards, Bernard (2003). Beware of raiders!

German surface raiders in World War II . Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-210-0. - Gardiner, Robert and Chenault, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's Fighting Ships of the World, 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9.

- Groener, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945

. Vol. I: Major surface vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. - Grützner, Jens (2010). Kapitän zur See Ernst Lindemann: Der Bismarck-Kommandant - Eine Biographie

(in German). VDM Heinz Nickel. ISBN 978-3-86619-047-4. - Hummelchen, Gerhard (1976). Die Deutschen Seeflieger 1935–1945

(in German). Munich: Lehmann. ISBN 978-3-469-00306-5. - Mayer-Welker, Hans; Forstmeier, Friedrich; Papke, Gerhard and Petter, Wolfgang (1983). Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648–1939

. Herrsching: Pawlak. ISBN 978-3-88199-112-4. - O'Hara, Vincent P.; Dixon, W. David and Worth, Richard (2010). On the Seas Contested: The Seven Great Fleets of World War II

. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-646-9. - Dad, Dudley (2005). The Battle of the River Plate: The Hunt for the German Pocket Battleship Graf Spee

. Ithaca: McBooks Press. ISBN 978-1-59013-096-4. - Rover, Jurgen (2005). Timeline of War at Sea, 1939–1945: A Naval History of the Second World War

. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8. - Showell, Jak P. Mallmann (2003). German naval code breakers

. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-308-6. - Watson, Bruce (2006). Atlantic Convoys and Nazi Raiders

. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98827-2. - Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II

. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4. - Williamson, Gordon (2003). German pocket battleships 1939–1945

. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-501-3. - Zetterling, Niklas and Tamelander, Michael (2009). Tirpitz: the life and death of Germany's last super-battleship

. Havertown: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-18-7.

Aircraft equipment

The main means of non-radar reconnaissance on cruisers was the Arado Ag.196 seaplane. A very decent seaplane, with a long flight range (1000 km) and good armament (two 20 mm cannons and three 7.92 mm machine guns plus two 50 kg bombs).

“Hipper” and “Blücher” each carried 3 seaplanes: two in single hangars and one on a catapult. The Prinz Eugen could carry up to five aircraft (4 in the hangar and 1 on the catapult), since it and subsequent ships in the series had dual hangars. But a complete aircraft kit was rarely accepted; usually ships of this series had 2-3 seaplanes.

Despite the fashion to abandon torpedo and aircraft weapons in favor of air defense systems, the cruisers retained their Arados until the end of the war.