| Caseless telescopic cartridge 4.7x33 "Dynamite-Nobel" |

The introduction of unitary cartridges with a metal sleeve in the 60s of the last century made it possible to dramatically improve the characteristics of small arms and paved the way for magazine and automatic systems. A metal sleeve, pressed against the walls of the chamber when fired by the pressure of powder gases, solved the problem of obturation; it also ensured the rigidity and strength of the ammunition and the possibility of their long-term storage. Very soon, such cartridges with a sequential arrangement of the bullet, powder charge and primer began to be called “classical” and actually determined the path of development of small arms down to the present day.

But, as you know, nothing in the world is perfect, and “metal” cartridges have their serious drawbacks. The need to remove the cartridge case from the chamber and remove it requires an increase in the stroke of automatic parts, special mechanisms, cutouts and grooves that increase the likelihood of dirt getting into the weapon. Anyone who has dealt with weapons knows that it is the mechanisms for extracting and ejecting a spent cartridge case that cause most of the failures and delays during shooting - non-extraction or breakage of the cartridge case, its sticking, non-reflection, jamming in the window. In addition, the sleeve has a relatively high dead weight and increases production costs. Weapons that fire from a closed volume (tank, armored vehicle, aircraft) need a device for collecting spent cartridges...

The search for ways to solve such problems has been and is still ongoing in different directions - this includes replacing metal cartridges with plastic ones (in “combat” cartridges this has not yet been possible), and the use of semi-burning cartridges with a small metal sealing pan, and changing the design of a unitary cartridge (“ U-shaped" cartridges, chamber cartridges for weapons with an "open chamber"). And finally, complete abandonment of the sleeve.

Systematic work on “caseless” cartridges and weapons for them began in different countries in the 60s of our century - a hundred years after the victory of “metal” cartridges - and required new materials and technologies. At the same time, many designers resort to modifications of old, seemingly forgotten ideas and designs. In 1966, the US Army command approved a three-year program to develop caseless 5.56 caliber cartridges at the Frankfort Arsenal; 7.62 and .20-30 mm, and the Rock Island Arsenal - weapons for them. Already by 1968, 23 thousand experimental 7.62-mm cartridges were shot, which included a standard cartridge bullet inserted into a combustible support sleeve, a cylindrical pressed charge of gunpowder and a primer; All elements were fastened with a layer of burning varnish. Compared to “classic” cartridges, the weight of caseless cartridges turned out to be lower by 45-53%, the volume - by 28-35%, the cost - by 10-25%: if the production of a metal sleeve required 13 technological operations, then the formation of a caseless charge required only four .

The AAI company developed a similar cartridge, but the bullet in it was contained in a plastic tray, which was discarded after leaving the barrel. Smith & Wesson developed a 9 mm caseless cartridge, 25 mm long and weighing 8.4 g, with a sequential bullet and charge arrangement and an electric primer at the end of the bullet's axial pin passing through the charge. It was tested using an M76 submachine gun (a conversion of the standard M3) with an electric trigger; the muzzle velocity was almost the same as that of a 9-mm Parabellum. The cessation of this work in the United States was associated not so much with the parameters and reliability of the cartridges, but with the difficulties of creating weapons for them.

In Europe, caseless ammunition was used in Belgium and Germany. The West German one turned out to be the most persistent - even after other participants in the work stepped aside, it, together with Dynamite-Nobel, continued development based on the technical requirements of the Bundeswehr. In 1974, it presented the first prototype and received a contract from the German Ministry of Defense, and in 1983 it presented a finished sample of a 4.7 mm assault rifle, designated G11. Since then, the G11 has been submitted for testing several times - in Germany it even passed military tests, and in the USA it took part in a competition for an “Advanced Combat Rifle” (ACR), but has remained experimental to this day. Nevertheless, a conversation about caseless weapons should start with it, as with the most proven system.

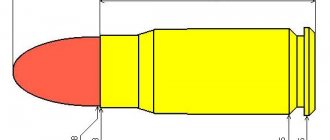

G11 – A PROMISING ASSAULT RIFLE FOR CASELESS AMMUNITION

The basis was the idea of a unitary cartridge with a completely burning cartridge case (completely burning paper cartridges were patented by Teri in 1843, and in 1855 by Prince). In the first version of the 4.7 mm Dynamite Nobel cartridge, a pointed bullet was pressed into the front part of a powder block coated with a burning varnish. Then a “telescopic” cartridge was developed - the bullet was “sunk” in a prismatic block, a plastic tip was placed in the head of the cartridge, protecting it from destruction during feeding and ensuring complete utilization of the powder charge. The primer and additional primer were placed behind the bullet. Caliber - 4.7 mm along the rifling fields, bullet diameter - 4.92 mm, cartridge length - 34 mm, prism side - 8 mm, bullet weight - 3.3 g, lateral load - about 20 g/sq.cm, initial speed - 914-930 m/s. Variants of cartridges with a tracer bullet, practical, blank and noise have also been created.

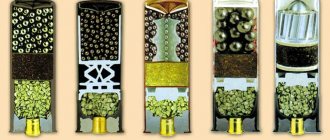

| Schematic diagram of power supply for G11 rifle cartridges |

Already in the first batches of cartridges, as expected, there were cases of spontaneous combustion of the propellant charge due to heating of the barrel and chamber, and even now this possibility raises doubts among a number of experts about the safety of the weapon: the high probability of spontaneous combustion is one of the main problems of caseless cartridges. Apparently, this is why a number of other companies chose to use a caseless cartridge in single-shot systems - this is what the American company did, which in the early 70s released a small batch of single-shot 5.6 mm rifles and V/L caseless cartridges (in these cartridges the charge was ignited by a jet of air heated under sharp compression), and the Austrian “Foere”, which in 1995 released single-shot VEC-91 rifles and a VEC-95 pistol chambered for a 5.56 mm cartridge with a cylindrical powder block (these systems were offered on the “commercial” market).

However, let's return to the design of the G11. It is built according to the “bullpup” design and makes maximum use of the advantages of a caseless cartridge. All mechanisms are assembled inside the case with a minimum of protruding elements. The weight of a G11 with 550 rounds of ammunition (7.35 kg) is equal to the weight of a 7.62 mm G3 assault rifle with 100 rounds or a 5.56 mm M16A2 with 240 rounds.

The operation of the G11 automation is based on the removal of powder gases from the muzzle of the barrel. The pressure of the gases forces the moving system, which includes a barrel with a locking mechanism, a percussion mechanism and a cartridge feeding mechanism, as well as a magazine, to mix back. In combination with the “hung” position of the moving system inside the body and the principle of “linear recoil”, this ensures a slight horizontal and vertical mixing of the weapon when firing, and the wide back of the butt helps to soften the impact of recoil on the shooter. The feed system includes a single-stack 50-round magazine positioned horizontally above the barrel and original feed and locking mechanisms using a “rotating chamber.” The chamber is made separately from the barrel in the form of a through diametrical channel in a cylinder rotating in a vertical plane. Behind the cylinder there is a bolt with a firing pin that is motionless relative to the barrel. In the normal position, the chamber is located coaxially with the bore. When moving back after a shot, the cylinder rotates 90° - so that the channel takes a vertical position (note that Hall's flintlock and capsule carbines of 1817 and Larsen's capsule rifle of 1842 already had a rotating chamber-chamber). The next cartridge is fed into the chamber by the feed lever, while powder gases or the misfired cartridge are pushed out of the chamber through the lower ejection channel. After this, the cylinder rotates, the axis of the chamber is aligned with the axis of the barrel bore. For manual control of the reloading system, a folding rotary handle is used.

Sectional view of the G11 rifle |

The G11 trigger mechanism provides single and continuous fire, as well as fire in fixed bursts of three shots. The double-sided safety switch has four positions: S - safety, 1 - single fire, 3 - bursts of three shots, 50 - continuous fire. An original feature of the G11 automatic, which the caseless cartridge made it possible to implement, is the principle of “impulse accumulation”, or “two-cycle automatic” - when the translator flag is set to “3” after pressing the trigger, the moving system comes to the rearmost position after three shots contract. The rate of fire during one such burst reaches 2000 rounds/min, and the burst turns into one shot without “shooting down” the aiming. Together with a very flat trajectory and insensitive recoil, this ensures high accuracy of fire and a high probability of hitting the target at the range of use of assault rifles (up to 400 m). At the same time, the short duration of this cycle does not reduce the survivability of the barrel. In continuous fire mode, the moving system returns forward after each shot, and the rate of fire ranges from 460 to 600 rounds per minute, which is considered optimal for firing long bursts from individual weapons.

Magazines are loaded directly from 25 (or 15) round packs. Thanks to the location of the magazine above the barrel, the rifle is well balanced. A carrying handle is placed above the center of gravity of the weapon, inside of which is mounted an optical sight with a 1x magnification and an aiming mark in the form of a ring - a sight without magnification does not narrow the shooter’s view of the battlefield, and the ring mark ensures quick aiming.

The weight of the G11 with a plastic body is 3.9 kg, length – 753 mm (with a barrel length of 537 mm), height – 317 mm, width – 71 mm. The G11 K2 modification, submitted to the ACR competition, featured a 45-round magazine, a mount for two spare magazines, a sight with variable magnification (from 1 to 3.5x), and the ability to replace the handle with a bracket for the M845 “Litton” sight.

In 1987, Heckler und Koch introduced a light machine gun (G11 LMG) based on the G11 and chambered for the same cartridge, but with a modified power system. The butt contained a magazine-hopper for 300 rounds (again a return to the old idea, this time - a butt magazine), equipped at the factory. The cartridge feeding mechanism was mounted in the widened middle part of the weapon and included a revolver block with three chambers - the revolver feeding of cartridges prevented them from overheating and self-ignition at a high combat rate of fire. The folding front handle was used for reloading. The weight of the equipped light machine gun was 7 kg, length - 940 mm, height - 310 mm, width - 85 mm.

History[edit]

Volcanic .41 Cartridge

An early predecessor to modern caseless ammunition, Walter Hunt's Rocketball cartridge, was developed in the 1850s, and weapons using them were sold at the time, primarily by Volcanic Repeating Arms. These cartridges were extremely low-power and were never widely used for self-defense, hunting or military use. [2]

During World War II, Germany began an intensive program of research and development of practical caseless ammunition for military use, driven by a growing shortage of metals, especially copper, used to make cases. The Germans had some success, but not enough to produce a caseless cartridge system during the war. [3] Japan successfully developed the Ho-301 40mm autocannon during the war for installation on aircraft. During the final months of the war it was used, albeit to a relatively limited extent, to defend Japan's home islands.

ITALIAN SUBMACHINE PISTOL SV-M2 FOR CASELESS PATROL AUPO

The path to creating caseless ammunition with solid powder (liquid or gaseous propellants is a topic for another discussion) and a kinetic destructive element, chosen by Heckler und Koch and Dynamite-Nobel, is not the only possible one.

Thus, already in 1982, the Italian proposed the SV-M2 submachine gun for the 9-mm caseless AUPO cartridge developed by Fiocci: if the Germans placed the bullet inside the powder charge, then the Italians, using the relatively large caliber of the cartridge, did the opposite - they placed the charge inside bullets, and the impact composition is around its solid head (it is worth remembering that a bullet with a propellant charge inside was patented by Taylor back in 1847). The Benelli SV-M2 submachine gun served rather to demonstrate the capabilities of the cartridge and therefore contained few innovations.

Since the “sleeve” open at the back is not capable of ensuring obturation of the chamber itself, a special free bolt rod, equipped with obturating grooves, “locked” the sleeve; In the event of a misfire, it also ensured that the cartridge was removed from the chamber. The trigger was mounted above the chamber and struck a vertical firing pin, which initiated the cartridge's primer belt. An interesting feature was the movement of the bolt at an upward angle to the axis of the bore, which made it possible to lower the barrel almost to the level of the pistol grip. The submachine gun was equipped with a box magazine for 40 rounds, the rate of fire reached 1000 rounds/min. - impressive, but not very interesting from the point of view of increasing accuracy and accuracy of fire.

And the weight of the SV-M2 reached 3.9 kg. As for the AUPO cartridge, it had a significant drawback: after the charge burned out, the bullet quickly lost speed and gave a large dispersion (by the way, the same drawback was characteristic of “reactive” bullets). Of course, after leaving the barrel, the “case” can be discarded, but this requires high manufacturing precision so that the process of its separation does not introduce serious disturbances into the movement of the bullet, and parts of the case turn into unsafe fragments. This can be partly corrected by introducing a plastic shell sleeve, which, in addition, would reduce friction when the bullet moves along the barrel and prevent the formation of soot.

And that's not it

The text is long, but much has not yet been said.

If the community approves, a sequel will be released about underwater, silent and non-cylindrical cartridges, which do not even look like cartridges (one of them can be seen in the title picture). And then, you see, I’ll prepare material about real space landing projects. PS Longreads take a long time to write, but I regularly share weapons finds on the Telegram channel GunFreak and keep notes about peaceful technologies, useful services, home 3D printing and my other hobbies in GeeksNote. Check out the upcoming invitation giveaway on BitSpyder.

With a belt

(eng. Belted) The purpose of the "belt" on cases (often called a "belted magnum" or "belted" case) is to create a mirror gap due to a special annular protrusion on the case just above the extractor groove. The belt plays the role of a flange on a sleeve without a flange. The shape of the groove for the extractor in such cartridges is completely similar to the wafer type. The diameter of the flange can be equal to the diameter of the collar or the base of the sleeve. Such cartridges are gradually losing their former popularity due to the popularization of high-power cartridges with rimless cartridges.

.375 H&H Magnum Case without rim. Flange diameter equals base diameter (30-378 Weatherby Magnum)

The design appeared in England around 1910 on the .400/.375 Belted Nitro Express cartridge (also known as .375/.400 Holland & Holland and .375 Velopex). Adding the collar gave the cartridge the correct mirror clearance despite the lack of case shoulder (tapering towards the ball in bottle shaped cartridges). The reason for this deficiency was that the old British cartridges were designed to use cordite rather than modern smokeless powder. Cordite was made in the form of pasta-like rods, so to accommodate the rods, the shape of the sleeve had to be close to cylindrical. The belt was added to other cartridges that were based on the .375 Velopex cartridge, such as the 1912 .375 Holland & Holland Magnum, to prevent the use of powerful magnum cartridges in chambers of similar sizes.

At the end of the 20th century in the United States, belted cartridges became synonymous with heavy-duty Magnum cartridges. Recently [ when?

] new Magnum cartridges were introduced in the USA. These are rimless or reduced rim cartridges based on the .404 Jeffery, with rims that match the .512″ size used for belted cartridges.

At the same time, the belt is often used for cartridges of small-caliber automatic guns, because the geometry of the cartridge case with the belt allows simple direct feeding of cartridges from the cartridge belt and at the same time the cartridges are well positioned in the chamber with the correct mirror gap. This makes it possible to somewhat increase the reliability of the automation of automatic guns, which is especially important for aviation.

The designation of such cartridges includes the letter “B”. For example, 7.62×67mm B, 20×105mm B, 20×138mm B, 23×152V, 30×113B, 30×155V and others.

External links [edit]

- History of assault rifle ammunition

| vteFirearms with caseless ammunition | ||

| ||

| vteNew technologies | |

| Fields |

- Collingridge's dilemma

- Differential technological development

- Disruptive Innovation

- Ephemeralization

- Ethics Bioethics

- Cyberethics

- Neuroethics

- Robot ethics

- Research Engineering

- Fictional technology

- Proactional principle

- Technological changes

- Technological convergence

- Technological evolution

- Technological paradigm

- Technology Forecasting

- Scanning the horizon

- Moore's Law

- Technological feature

- Scouting technologies

- Level of technological readiness

- Technology Roadmap

- Transhumanism

- Technological unemployment

- Accelerating change

- Category

- List

Links[edit]

- ^ abc Meyer, Rudolf; Köhler, Joseph; Homburg, Axel (2007). Explosives . Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31656-4.

- "volcanic - Search results - Winchester Collector". winchestercollector.org

. - ^ ab Barnes, Frank S. Skinner, Stan (eds.). Cartridges of the World

(10th ed.). Krause Publications. clause 8. ISBN 0-87349-605-1. - ^ a b "Voer". Archived from the original on 2008-06-13.

- ^ abc Margiotta, Franklin D. (1997). Brassey's Encyclopedia of Land Forces and Wars

. Brassey. ISBN 9781574880878. - ^ abc DiMaio, Vincent J. M. (1998). Gunshot wounds. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8163-8.

- Ackley, P. O. (1962). A Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders

.

I

. Plaza Publishing House. ISBN 978-99929-4-881-1. - See main article, Chassepot, for links.

- Fjestad, IP Blue Book of Pistol Values

(13th ed.). Blue Book Publications. - Administrator. “The new 40-mm automatic grenade launcher AGS-40 “Balkan” will enter service with the Russian army. TASS 11311161 - Weapons of the defense industry, military equipment of Great Britain - analytical direction army, defense industry, military industry, army." www.armyrecognition.com

. - "Lenta.ru: Weapons: Armament: Russia will arm itself with a new large-caliber grenade launcher". Lenta.ru. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "Modern Firearms". World.guns.ru. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Starry, Donn A., General. Horse fighting in Vietnam.

Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1978.

Lockless cartridge

The next type of polymer cartridges was invented in 1967 by designer Maurice Goldin, an employee of the helicopter manufacturing company Hughes Helicopters. For their vague resemblance to the pads of popular chewing gum, contemporaries nicknamed them chiclets, but in documents this ammunition appears under the name lockless.

The lockless cartridge was a hollow plastic parallelepiped divided into three parts by partitions.

The bullet was placed in the middle, while the bulk of the gunpowder was poured into the side chambers. To make the cartridge more compact, Goldin used staged ignition. At first, the primer ignited a small amount of explosive. It was enough to move the bullet, plug the hole in the front of the plastic casing and seal it. When the bullet moved, holes leading into the side chambers opened and the main volume of gunpowder was ignited, sufficient to push the bullet out of the barrel.

The result is a very dense layout. Lockless were significantly lighter than conventional cartridges of the same caliber and took up 54% less space.

Commissioned by the famous gunsmith James Sullivan, Maurice Goldin designed a prototype weapon chambered for a new cartridge. It was loaded from the side, through one of the two windows in the receiver. Each subsequent cartridge simply squeezed the previous one out of the chamber, and before firing the holes were closed by a sliding sleeve.

The military only learned about lockless cartridges in 1986-1988. By this time, McDonnell Douglas Helicopter had separated from Hughes Helicopters, which entered into a contract with Picatinny Arsenal and agreed to participate in the next program to develop weapons of the future - Advanced Combat Rifle (ACR).

Goldin's patents formed the basis for an improved rifle, which had a magazine for ten rectangular cartridges. It’s just that McDonnell, it seems, considered the cartridge not revolutionary enough and began to make changes to the drawings that the designer had been thinking through since the late sixties.

It is clear from surviving ACR program documents that McDonnell Douglas engineers first tried to fit two or three bullets into a lockless cartridge, and then tried several different types of darts until they settled on three, packaged in a .338 (8.6 mm) cartridge.

It was with these cartridges that the prototype was tested in May 1988, and by June McDonnell Douglas dropped out of the competition early due to the hardware immaturity of its rifle. Darts from hastily converted ammunition simply flew past the target.