Ancient edged weapons and armor of India (42 photos)

For many hundreds of years, Europeans considered precious stones to be the main treasures of India. But in fact, its main wealth has always been iron. Indian steel has been highly valued since the time of Alexander the Great and was used to produce the highest quality and most expensive weapons.

The famous centers of weapons production in the medieval East were Bukhara and Damascus, but... they received metal for it from India. It was the ancient Indians who mastered the secret of producing damask steel, known in Europe as Damascus. They also managed to tame and use elephants in battles, and just like their horses, they dressed them in armor made of chain mail and metal plates!

In India, several grades of steel of varying quality were produced. The steel was used to produce various types of weapons, which were then exported not only to the markets of the East, but also to Europe. Many types of weapons were unique to this country and were not used anywhere else. If they were bought, they were considered as a curiosity.

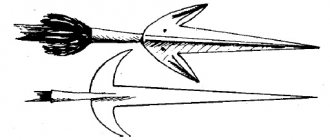

Chakra, a flat throwing disc used in India until the mid-19th century, was very dangerous in the right hands. The outer edge of the disk was razor-sharp, and the edges of its inner hole were blunt. When throwing, the chakra was vigorously spun around the index finger and thrown at the target with all its might. After this, the chakra flew with such force that at a distance of 20–30 m it could cut through the trunk of a green bamboo 2 cm thick. Sikh warriors wore several chakras on their turbans at once, which, among other things, protected them from above from a saber strike. Damask chakras were often decorated with gold notches and had religious inscriptions on them.

In addition to ordinary daggers, the Hindus very widely used the katar - a dagger with a handle perpendicular to its longitudinal axis. At the top and bottom there were two parallel plates, ensuring the correct position of the weapon and at the same time protecting the hand from someone else’s blow. Sometimes a third wide plate was used, which covered the back of the hand. The handle was held in a fist, and the blade was like an extension of the hand, so the blow here was directed by the stronger muscles of the forearm, rather than the wrist. It turned out that the blade was an extension of the hand itself, thanks to which they could strike from various positions, not only standing, but even lying prone. The Cathars had both two and three blades (the latter could stick out in different directions!), they had sliding and curved blades - for every taste!

Madu. A very original weapon was a pair of antelope horns, which had steel tips and were connected on one handle together with a guard to protect the hand, with points in different directions.

Nepal was the birthplace of the kukri knife, which has a specific shape. It was originally used to cut a path through the jungle, but then found its way into the arsenal of the Nepalese Gurkha warriors.

Not far from India, on the island of Java, another original blade was born - the kris. It is believed that the first kris were made in Java by a legendary warrior named Juan Tuaha back in the 14th century. Later, when Muslims invaded Java and began to persistently spread Islam there, they also became acquainted with these weapons. Having appreciated these unusual daggers, the invaders began to use them themselves.

The blades of the first kris were short (15–25 cm), straight and thin, and were made entirely of meteorite iron. Later they were somewhat lengthened and made wavy (flame-shaped), which facilitated the penetration of weapons between bones and tendons. The number of waves varied (from 3 to 25), but was always odd. Each set of curves had its own meaning, for example, three waves implied fire, five were associated with the five elements, and the absence of curves expressed the idea of unity and concentration of spiritual energy.

The blade, made of an alloy of iron and meteorite nickel, consisted of several repeatedly forged layers of steel. What gave the weapon special value was the moiré-like pattern on its surface (pamor), formed when the product was treated with plant acids, so that the grains of stable nickel stood out clearly against the background of deeply etched iron.

The double-edged blade had a sharp asymmetrical extension near the guard (ganja), often decorated with an incised ornament or a patterned notch. The handle of the kris was made of wood, horn, ivory, silver or gold and was carved, with a more or less sharp bend at the end. A characteristic feature of the kris was that its handle was not fixed and easily turned on the shank.

When gripping a weapon, the curve of the handle was placed on the little finger side of the palm, and the upper part of the guard covered the root of the index finger, the tip of which, together with the tip of the thumb, squeezed the base of the blade near the bottom of the ganja. The tactics for using kris involved a quick thrust and pull. As for the “poisoned” kris, they were prepared very simply. They took dried dope seeds, opium, mercury and white arsenic, mixed everything thoroughly and crushed it in a mortar, after which the blade was covered with this composition.

Gradually, the length of the kris began to reach 100 cm, so that in fact it was no longer a dagger, but a sword. In total, in Southeast Asia to this day there are more than 100 varieties of this type of weapon.

The Kora, Khora or Hora is a heavy striking sword from Nepal and northern India, used for both martial and ritual purposes. Martial and ritual koras are very similar, only the sacrificial sword is wider and heavier. It has a very heavy flared pommel, as it must add weight to the blade and decapitate the sacrificed animal in one blow. The kor blade has a characteristic duck's foot profile, thin near the hilt, with a blade flaring towards the tip with a slightly curved blade. The massive blade has a curved shape, sharpened on the inside. Sometimes a fuller is used in the form of a wide groove located along the entire length of the blade and replacing the rib. The presence of several edges allows you to strike with different parts of the sword. The total length of the sword is 60-65 cm, the length of the blade is 50 cm. The guard is ring-shaped, made of metal and has the shape of a disk. Often the guard is placed both on the side of the blade and on the side of the pommel, and protects the hand on both sides. The kora is usually decorated with an eye symbol or other Buddhist symbolism, which is placed on each side of the blade. Sheath made of genuine leather. There are two types of kor sheaths: a scabbard adapted to the shape of the sword, unfastened by means of buttons located along the entire length of the sheath. In another version, the large sheath looks like a carrying case. There is a kora model with a longer and lighter blade.

Sword puttah bemoh A two-handed sword or sword with a long narrow straight blade and two handles separated by guards in the form of crosses or cups. It was first mentioned in the 16th century treatises “Nihang-nama” and “Nujum al-Ulum”. Several copies of such swords have survived. One of them has a total length of 165 cm and a blade length of 118 cm. The handle is divided into two parts, each of which is equipped with a cup-shaped guard. The blade is quite narrow, similar to a sword blade. It is believed that these swords arose in the 16th century, perhaps under the influence of the German Zweihanders, and were later replaced by Khanda weapons. However, the mel puttah bemokh has an important difference from European two-handed swords - a narrow and relatively light blade, which was not so effective for delivering slashing blows.

In general, the edged weapons of India and the lands close to it were extremely diverse. Like many other peoples of Eurasia, the national weapon of the Hindus was a straight sword - the khanda. But they also used their own types of sabers, which were distinguished by a relatively slight curvature of the wide blade, starting from the very base of the blade. Excellent forging masters, the Indians could make blades that had a slot on the blade, and pearls were inserted into it, which rolled freely in it without falling out! One can imagine the impression they made as they rolled into the slots on an almost black blade made of Indian damask steel. The hilts of Indian sabers were no less rich and elaborate. Moreover, unlike the Turkish and Persian ones, they had a cup-like guard to protect the hand. It is interesting that the presence of a guard was also typical for other types of Indian weapons, including even such traditional ones as a mace and a shestoper.

Talwar - Indian saber. The appearance of the talwar is typical for sabers - the blade is of medium width, slightly curved, sharpening can be one and a half, but this is not necessary. There are variants of the talwar both with and without elmanya. There may be a fuller on the blade of the talwar, but most often it is not there. In some cases, the valley may even be end-to-end; movable balls made of various materials are sometimes inserted into it. The main difference between the talwar and other sabers is, first of all, its disc-shaped pommel of the hilt. Also, this saber must have a “ricasso” (heel), even if it is small. The length of the blade can be from 60 to 100 cm, width - from 3 to 5 cm. The handle of the talwar is straight, with a thickening in the middle, and is designed exclusively for one hand. The disc-shaped pommel prevents the weapon from being lost and gives this saber a unique look. It is often richly decorated, as are the hilt and guard. The latter can have either a straight shape, or an S-shaped or D-shaped one. The ornaments decorating the talwar usually contain geometric shapes, images of animals and birds. On the weapons of the rich you can see inlay with precious stones or enamel.

The Talwar has been around since the 13th century and was a very popular weapon in northern India. Especially among the Rajputs, representatives of the Kshatriya caste, who used these weapons right up to the 19th century. In addition to military, the talwar also has a certain sacred purpose. According to mythology, it is one of the ten weapons of the gods, with the help of which the forces of good fought against demons and other evil.

Pata or Puddha is an Indian sword with a long, straight, double-edged blade that is connected to a gauntlet, a steel guard that protects the arm up to the elbow.

Pata is a combination of a straight, double-edged sword and armor protection for the forearm and hand. The blade fits into a protective cup with a handle inside. The pat has a handle perpendicular to the blade, just like a katar, but there are several belts on the armor to secure the hand. Pata blades were from 60 to 100 cm with a hilt width of 35-50 mm. The weight reached 1.5 - 2.2 kg. The pata blade was fastened with rivets to plates extending from the protective cup. The pata cup covering the hand was often made in the shape of the head of an elephant, snake, fish or dragon. In this case, the blade extended from the open mouth like a huge tongue. Another popular cup shape motif is the mythical Yali lion swallowing an elephant.

Apparently, the pata developed at one time from the katar (Indian dagger), going through several modifications of the guard and becoming hypertrophied. First, a protective plate was added to the catarrh to cover the wrist, then it was connected to the side metal strips. This design gradually transformed into a “plate glove” that covered the arm up to the elbow. The “handle glove” could be of a skeletal type - made of crossed metal strips (probably earlier forms) or made in the form of the heads of mythical animals. According to another version, it’s the other way around - in the beginning there was stata, from which the cathars originated by simplifying the design. But the truth is that both Qatar and Pata were in service during the same period of history.

Bhuj (also kutti, gandasa) is an Indian glaive-type weapon. It consists of a short handle (about 50 cm) connected to a massive blade in the form of a knife or cleaver. Thus, this weapon is similar to the short variants of the palm or dadao. In the classic version, the bhuja blade was quite wide and had a one-and-a-half sharpening, while it was distinguished by a double bend: closer to the handle it was concave, and towards the tip it was curved, so that the tip was directed upward relative to the handle. Along the center of the blade, from the tip to the level at which the butt began, there was a stiffening rib. The handle was often made of metal (steel, bronze, copper), less often of wood. In some cases, the bhuj was accompanied by a scabbard, usually made of wood and covered with velvet. Thanks to the massive blade, this weapon could deliver powerful slashing blows, which is why one of its names meant “knife-axe.” In addition, the junction of the blade with the handle was sometimes made in the form of a decorative elephant’s head, which is where another name comes from: “elephant knife.”

The name "bhuj" is derived from the city of the same name in Gujarat, where this weapon originates. It was widespread throughout India, especially in the north. There were also rarer variants, for example, those that had a handle with a guard, or that had a different blade shape. A bhuj is also known, combined with a percussion pistol, the barrel of which is located above the butt of the blade; A stiletto is inserted into the end of the handle opposite the blade. In southern India, an analogue of the bhuja was used - the verchevoral, which had a concave blade and was used to cut through thickets.

Driven - a klevet used in India in the 16th - 19th centuries. Its name comes from the Persian word meaning “crow’s beak”, since this was the shape of the warhead. The beak was made of steel in the form of a rather thin dagger blade, usually with a stiffening rib or fullers. The tip sometimes curved down towards the handle, in other cases the blade was straight. On the butt there was sometimes a decorative bronze figurine depicting, for example, an elephant. Less often, a small ax was made instead - such a weapon was called a tabar-driven.

Mints of other types were less common. In particular, peckers with a round cross-section or faceted beak were in circulation. Quite exotic artifacts have also been preserved, one of which has 8 beaks at once, secured so that 2 were directed in each of the four directions, and ax blades are attached between them. Another specimen is similar to a tonga ax with a double forward-pointing tip. The handle of the coins was made of wood or metal. Sometimes a stiletto could be inserted into the hollow metal handle on the opposite side of the combat part. These coins were one-handed weapons. Their total length ranged from 40 to 100 cm.

Haladi dagger. The haladi had two double-edged blades connected by a handle. It was an attack weapon, although the slightly curved blade could easily be used for parrying. Some types of khaladi were made of metal, and were worn like brass knuckles, where another spike or blade could be located. These types of khaladi were perhaps the world's first three-bladed daggers.

Urumi (lit. - twisted blade) is a traditional sword, common in India in the northern part of Malabar. It is a long (usually about 1.5 m) strip of extremely flexible steel attached to a wooden handle. The excellent flexibility of the blade made it possible to wear the urumi concealed under clothing, wrapping it around the body.

In some cases, the length of such a sword could reach six meters, although one and a half meters can be considered the standard. Previously, such flexible swords were worn by assassins, remaining unnoticed for weapons. After all, this sword, as already mentioned, is very flexible, and can be wrapped around a belt. A flexible sword is a rather dangerous weapon that requires martial arts. It can work both as a regular whip and as a sword. Interestingly, urumi can have more than one stripe, but several, which makes it a powerful and very dangerous weapon in the hands of a true master. Wielding this sword required good skills. Due to the fact that the urumi was very flexible, there was a serious risk of self-harm for the owner. Therefore, beginners began training with long pieces of fabric. Mastery of urumi is included in the complex of the traditional South Indian martial art of Kalaripayattu.

Kalaripayattu, as a martial art, was developed in the second half of the 16th century, despite the prohibitions of the British colonialists, who feared the emergence of an uncontrolled fighting structure. But, despite the bans, schools continued to train Kalaripayattu fighters. The primary rule of martial art for a warrior was perfect control of his body. The battle took place in conditions of incessant movement, instant lunges and dodges, jumps, coups and somersaults in the air. The Kalaripayattu fighter was armed with a saber or dagger, a trident or a pike with a steel tip. Some masterfully wielded a long, double-edged sword. But the most terrible weapon was the Urumi sword. Several flexible blades, sharp as a razor, about two meters long, extended from the handle. The fight could have ended in the first second, since Urumi's movement was completely unpredictable. One swing of the sword sent the blades to the sides and their further movement was unpredictable, especially for the enemy.

The complex oriental bow was also well known in India. But due to the characteristics of the Indian climate - very humid and hot - such onions are not widely used. Having excellent damask steel, the Indians made small bows from it, suitable for horsemen, and bows for infantrymen were made of bamboo in the manner of the solid wooden bows of English archers. Indian infantry of the 16th–17th centuries. had already quite widely used long-barreled matchlock muskets equipped with bipods for ease of shooting, but there were always not enough of them, since it was extremely difficult to produce them in large quantities during craft production.

A feature of Indian striking weapons was the presence of a guard even on poles and maces.

Very interesting were Indian chain mail with a set of steel plates on the front and back, as well as helmets, which were used in India in the 16th–18th centuries. often made from separate segmental plates connected by chain mail weaving. Chain mail, judging by the miniatures that have come down to us, had both long and short sleeves up to the elbow. In this case, they were very often supplemented with bracers and elbow pads, often covering the entire hand.

Over the chain mail, mounted warriors often wore smart, bright robes, many of which had gilded steel discs on the chest as additional protection. Knee pads, leg guards and leggings (chain mail or in the form of solid forged metal plates) were used to protect the legs. However, in India, metal protective shoes (as in other countries of the East), unlike the protective shoes of European knights, never became widespread.

Indian shield (dhal) from Rajasthan, 18th century. Made of rhinoceros skin and decorated with rock crystal umbons.

It turns out that in India, as well as in all other places, right up to the 18th century, the weapons of heavily armed cavalry were purely knightly, although again not as heavy as they were in Europe until the 16th century. Horse armor was also widely used here, or at least cloth blankets, which in this case were complemented by a metal mask.

Kichin horse shells were usually made of leather and covered with fabric, or they were lamellar or lamenar shells made of metal plates. As for horse armor, in India, despite the heat, they were popular until the 17th century. In any case, from the memoirs of Afanasy Nikitin and some other travelers, it can be understood that they saw cavalry there “entirely dressed in armor,” and the horse masks on the horses were trimmed with silver, and “most were gilded,” and the blankets were sewn from multi-colored silk, corduroy, satin and “Damascus fabrics”.

Bakhterzov armor for a war elephant, India, 1600

This is the most famous armor for the war elephant. It is on display at the Royal Armories in the English city of Leeds. It was made around 1600, and it arrived on the shores of Foggy Albion 200 years later. Elephants fought in this armor in Northern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Today this is the largest elephant armor in the world, which is officially registered in the Guinness Book of Records.

Scale armor for a war elephant, India, 17-18 centuries

Metal plates are sewn onto a base, such as leather. Some of the plates are made of yellow metal, like tiles. Each plate overlaps several neighboring ones, which allows for stronger protection and thinner plates. Thanks to thinner and lighter plates, the weight of the entire armor is also reduced.

Plate armor for a war elephant

Legacy of the Gods

The people of India in life, everyday life and on the battlefield have always relied on ancient sacred teachings and treatises. Like many other attributes, the chakra throwing weapon, as it is called in its homeland, was an imitation of a powerful fiery disk with a hole inside, which was used in the wars of gods, demons and people in the Indian epics “Mahabharata” and “Ramayana”. According to legends, it was created by the gods: Brahma himself fanned the fire for it, Vishnu put in a piece of divine anger and passed the workpiece to Shiva, who endowed the weapon with the power of his third eye and pressed it all into a fiery disk with his foot, which cut off the head of the demon Jalamdhar himself.

Materials, sizes, types

The deadly disc has become an integral part of Indian culture and fighting techniques. To make chakra, copper or steel strips were used, the width of which varied from 10 to 40 mm, and the thickness reached 3.5 mm. Accordingly, the diameter of the finished product could be 120-300 mm. If we turn to Fakhr al-Din’s treatise “The Art of War,” which was written in the 13th century, we learn that it indicated that the disk itself was of two types: a lighter one with a hole and a heavier one without a hole. But an unusual type of this ancient weapon was used in Ceylon. It could be characterized by the succinct phrase “spiked chakram”, since it had a jagged outer edge, but in the local dialect its name sounded like “para wallalla”.

Art of War

Another treatise on military affairs called "Dhanurveda" described the Indian canonical throwing and small arms, and one of the twelve types was the chakram. Weapons that killed at a distance, without contact between the warrior and the victim, were the most revered in India, because they did not burden karma, which is very important for such a religious people. This is also one of the reasons why deadly discs were so sought after and second only to the bow, which was considered more advanced. Mastery of five types of weapons was part of the compulsory training program for young men from noble families; they were taught the correct technique from an early age. The sequence of using one or another weapon as it approached the enemy was also strictly determined. The first was a bow, the second was chakra, then a sword and a spear were used, and very close - a mace and a knife. As a last resort, unarmed combat techniques were also studied.

Chakram - a weapon of antiquity

Unfortunately, mere mortals do not have the power of the gods. Despite the beautiful legend, there is still no exact understanding of where this deadly ring came from in Indian traditions. Disputes related to its origin have not subsided to this day. According to the main hypothesis, even in the Neolithic era, ancient people used stone as a throwing projectile, and already in the Stone Age this object acquired polished sharp edges along its entire perimeter. This hypothesis is confirmed by recent finds at archaeological excavations in the north of the country. Thus, chakram is a weapon that has made its way from an ordinary stone to a perfect metal form.

Analogues in other cultures

Chakras are the throwing weapons of India, but other ancient nations also created something similar. The closest analogue is the Chinese throwing plates, called “poor man's coins,” made of bronze and reaching a diameter of 60 mm. Sometimes they were also sharpened along the edge.

“Fei Pan Biao” is another creation of the Chinese. These plates resemble modern circular saw blades, closer to the “spiked chakrams” of Ceylon. Also, the Land of the Rising Sun has its own analogues of deadly disks, which are more famous than chakras. These are multi-rayed stars - shurikens. However, the biggest difference between these types of weapons is not the form, but the method of use. Throwing plates from other countries were used secretly, in the shadows, as weapons of assassins, while chakras were widespread, used openly and on a large scale - in major battles and beyond.

Real craftsmanship

Travelers of those centuries, and everyone else who saw and described the capabilities of the formidable disk in battle, admired its deadly power, harmonious perfection and technique of use. Indian chakram throwing weapons could cut off an enemy's limb, and its flight range could reach one hundred meters, although the most convenient distance for striking was 50 meters. The art of using chakram was not publicly available; it was a privilege only of aristocratic families, whose offspring began their training from early childhood. It is quite natural that in inept hands a deadly disc could do more harm than good, and cripple not so much the enemy as the thrower himself and those around him. The chakra throwing technique also had its own nuances. So, there were several ways to throw. The warrior could spin the throwing disc on the middle finger or rod and point it towards the enemy, in another case the ring was clamped between the palm and thumb, like a modern flying saucer. And also, thanks to many different techniques, warriors threw chakras not only horizontally, but also vertically, and even in series.