Author: zaCCCPanec

October 20, 2022 04:10

Tags: day in history riddles battleship Empress Maria secrets

8159

19

On October 20, 1916, the newest Russian battleship Empress Maria exploded in the bay of Sevastopol.

0

See all photos in the gallery

In Soviet times, boys and girls read the adventure story “Dirk” by Anatoly Rybakov. The plot of the story was connected with a relic, for the sake of acquiring which one of the negative characters committed murder and blew up the battleship "Empress Maria". The version of the writer Rybakov has a right to exist. If only because 100 years after the death of the battleship, which actually existed, the causes of this tragedy have not been established.

To spite the Turkish adversary.

0

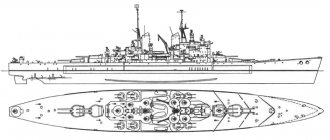

In 1911, at a shipbuilding plant in Nikolaev, a series of Russian battleships were laid down, which were supposed to confront the latest Turkish warships in the Black Sea. A total of four ships were planned, of which three were completed - “Empress Maria”, “Emperor Alexander III” and “Empress Catherine the Great”.

×

0

0

The battleship "Empress Maria" after launching, October 19, 1913.

The lead ship of the series was the battleship Empress Maria, laid down along with two other ships on October 17, 1911. The Empress Maria was launched on October 19, 1913.

0

The ship received its name from the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of the late Emperor Alexander III.

0

The battleship was equipped with four 457 mm torpedo tubes, twenty 130 mm guns, and turrets of 305 mm main caliber guns.

0

The battleship Empress Maria leaves the factory, June 24, 1915.

0

The completion of the ship was completed at the height of the First World War, at the beginning of 1915, and on June 30 the battleship arrived in Sevastopol. During sea trials, shortcomings were identified that had to be quickly corrected. In particular, due to the bow trim, it was necessary to lighten the bow section. It was also noted that the ventilation and cooling system of the artillery magazines was poorly designed, which is why the temperature remained high there. But on August 25, 1915, the battleship entered service.

The fleet is deadly to itself

The French navy of the early 20th century was considered the most dangerous in the world. Explosions on warships occurred regularly. The American magazine Popular Mechanics (Chicago) wrote in November 1911: “The explosion of the powerful French battleship Liberté in Toulon harbor in the early morning of September 22 added another line to the fatal list of disasters that have brought the French military in the last five years The fleet has a reputation as the most dangerous to itself among all navies in the world. In Toulon alone, which is the largest naval base in France, during this time a total of more than 400 people have already died.”

Next, the Americans give a list of tragedies:

February 1907. Explosion of a torpedo boat. 9 people died. March 1907. Explosion of the battleship Jena. 107 dead (according to other sources - 118). August 1908. Explosion of a training artillery ship. 6 dead. September 1910. Explosion on a cruiser. 13 dead. September 1911. Explosion on the cruiser Gloire. 6 dead. September 1911. Explosion of the battleship Liberté. About 300 dead.

The battleship Charlemagne is the first in its class. Entered service in 1899. Was the predecessor and prototype of the squadron battleship "Jena"

Image from the collection of Peter Kamenchenko

A series of tragedies had such a profound effect on the morale of the French naval personnel that sailors began to imagine explosions on their own ships, and the slightest appearance of smoke often ended in a panicked flooding of the ship's powder magazines and, accordingly, the destruction of gunpowder reserves.

At the same time, it turned out that in the event of a real fire, this measure was completely ineffective, since about ten valves had to be opened to flood each powder magazine. Moreover, each of them opened only after 15-20 turns of the flywheel, and they could only be opened from the lower deck. But even if the crew managed to do this quickly, the water simply would not flow into a closed room, moreover, filled with gas under high pressure.

“There are many rescued, their number is being clarified”

0

At the end of 1915 - beginning of 1916, the Empress Maria successfully operated as part of the Black Sea Fleet. In the summer of 1916, the battleship became the flagship of the new fleet commander, who became Vice Admiral Kolchak.

0

The battleship "Empress Maria" during the Highest Review in Sevastopol, May 12, 1916.

On October 20, 1916, at 6:20 a.m., a powerful explosion occurred under the bow tower of the Empress Maria, which stood in the bay of Sevastopol. Over the next 48 minutes, about a dozen more explosions of varying power occurred, as a result of which the battleship sank.

0

Fleet Commander Kolchak arrived at the scene of the disaster and personally supervised the rescue of the sailors. At 8:45 he sent a telegram to Nicholas II: “Today at 7 o’clock. 17 min. On the roadstead of Sevastopol, the battleship "Empress Maria" was lost. At 6 o'clock. 20 minutes. An internal explosion occurred in the bow magazines and an oil fire started. The remaining cellars immediately began to flood, but some could not be entered due to the fire. Explosions of cellars and oil continued, the ship gradually landed with its nose and at 7 o'clock. 17 min. overturned. There are many rescued, their number is being clarified. Kolchak." On the same day, Kolchak, in a telegram to the Chief of the General Naval Staff, Admiral Rusin, reported on the death of mechanical engineer midshipman Ignatiev and 320 “lower ranks.”

The mystery of the explosion of the battleship "Empress Maria"

On October 7, 1916, the largest ship of the Russian fleet at that time, the battleship Empress Maria, exploded in the Northern Bay of Sevastopol.

Along with the ship, the following were killed: a mechanical engineer (officer), two conductors (foremen) and 149 lower ranks - as stated in official reports. Soon, another 64 people died from wounds and burns.

In total, more than 300 people were victims of the disaster. Dozens of people became crippled after the explosion and fire on the Empress Maria. There could have been much more of them if at the time of the explosion that occurred in the bow tower of the battleship, its crew had not been standing in prayer at the stern of the ship. Many officers and conscripts were on shore leave before the flag was raised in the morning - and this saved their lives.5

The city and fortress of Sevastopol were awakened by explosions that echoed over the quiet surface of the Northern Bay, and the newest battleship of the Black Sea Fleet, engulfed in a black-fiery cloud, appeared to the eyes of people running to the harbor. What happened? At 6:20 a.m., the sailors, who were in casemate No. 4 at that time, heard a sharp hiss coming from the cellars of the main caliber bow tower, and then saw clouds of smoke and flames escaping from the hatches and fans located in the tower area.

One of the sailors managed to report to the watch commander about the fire, others rolled out hoses and began to fill the turret compartment with water. However, nothing could avert the catastrophe... “In the washbasin, putting their heads under the taps, the crew was snorting and splashing, when a terrible blow thundered under the bow tower, knocking half the people off their feet. A fiery jet, shrouded in poisonous gases of yellow-green flame, burst into the room, instantly turning the life that had just reigned here into a pile of dead, burned bodies... A new explosion of terrible force tore out the steel mast. Like a reel, he threw the armored cabin (25,000 poods) to the sky. The bow duty stoker flew into the air. The ship plunged into darkness. Mine officer Lieutenant Grigorenko rushed to the dynamo, but was only able to reach the second tower. A sea of fire raged in the corridor. Completely naked bodies lay in piles. Explosions were heard. The magazines of 130-mm shells were exploding. With the destruction of the duty stoker, the ship was left without steam. It was necessary to raise them at all costs in order to start the fire pumps. The senior mechanical engineer ordered the steam to be raised in stoker room No. 7. Midshipman Ignatiev, having gathered people, rushed into it. The explosions followed one after another (more than 25 explosions). The bow magazines detonated. The ship tilted to starboard more and more, plunging into the water. Fire rescue ships, tugboats, motors, boats, boats swarmed around... An order followed to flood the cellars of the second tower and the adjacent cellars of 130-mm guns in order to block the ship. To do this, it was necessary to penetrate into the battery deck, littered with corpses, where the flood valve rods came out, where the flames raged, suffocating vapors swirled, and the cellars charged with explosions could detonate every second. Senior Lieutenant Pakhomov (bilge mechanic) with selflessly brave people rushed there a second time. They pulled away charred, disfigured bodies, piles of piles piled up, and arms, legs, and heads were separated from their bodies. Pakhomov and his heroes freed the rods and applied the keys, but at that moment a whirlwind of draft threw pillars of flame at them, turning half of the people into dust. Burnt, but unaware of his suffering, Pakhomov completed the job and jumped out onto the deck. Alas, his non-commissioned officers did not have time... The cellars detonated, a terrible explosion captured and scattered them like fallen leaves like an autumn blizzard... People were stuck in some casemates, barricaded by lava fire. Go out and you'll burn. If you stay, you will drown. Their desperate cries sounded like the cries of madmen. Some, caught in fire traps, tried to throw themselves out of the portholes, but got stuck in them. They hung up to their chests above the water, and their legs were on fire. Meanwhile, work was in full swing in the seventh stoker. They lit fires in the fireboxes and, fulfilling the orders received, raised steam. But the roll suddenly increased greatly. Realizing the impending danger and not wanting to expose his people to it, but still believing that it was necessary to raise steam - maybe it would come in handy, - midshipman Ignatiev shouted: - Guys! Stomp up! Wait for me at the mezzanine. If you need me, I'll call you. I'll close the valves myself. People quickly climbed up the ladder's brackets. But at that moment the ship capsized. Only the first managed to escape. The rest, along with Ignatiev, remained inside... How long did they live and what did they suffer in the air bell until death relieved them of their suffering? Much later, when they raised the “Maria,” they found the bones of these heroes of duty scattered throughout the fireplace…”1

This is an eyewitness account of that terrible tragedy, senior flag officer of the Black Sea mine division, captain 2nd rank A.P. Lukina. And here is the timing of the disaster, taken from the logbook of the nearby battleship Eustathius: “6 hours 20 minutes - On the battleship Empress Maria there is a large explosion under the bow tower. 6 hours 25 minutes - A second explosion followed, a small one. 6 hours 27 minutes - Two small explosions followed. 6 hours 30 minutes - The battleship “Empress Catherine”, towed by port boats, departed from the “Maria”. 6 hours 32 minutes - Three consecutive explosions. 6 hours 35 minutes - One explosion followed. They lowered the rowing ships and sent them to "Maria". 6 hours 37 minutes - Two consecutive explosions. 6 hours 47 minutes - Three consecutive explosions. 6 hours 49 minutes - One explosion. 7 hours 00 minutes - One explosion. Port boats began to extinguish the fire. 7 hours 08 minutes - One explosion. The stem went into the water. 7 hours 12 minutes - The bow of the “Maria” sank to the bottom. 7 hours 16 minutes - “Maria” began to list and lay on the starboard side.”1

The battleship "Empress Maria", the first of a series of "Russian dreadnoughts" laid down before the First World War according to the designs of famous naval engineers A. N. Krylov and I. G. Bubnov, built at the shipyards of the Russian shipbuilding joint-stock company "Russud" in Nikolaev and launched on November 1, 1913, it was rightfully considered the pride of Russian shipbuilding. The ship received its name from the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, wife of the late Russian Emperor Alexander III. The Empress Maria was 168 meters long, 27.43 meters wide, 9 meters draft, had 18 main transverse watertight bulkheads, four propeller shafts with brass propellers with a diameter of 2.4 meters, and the total power of the ship's power plant was 1840 kW. When the first two of the four powerful, high-speed battleships laid down in Nikolaev - the Empress Maria and the Empress Catherine the Great - arrived in Sevastopol, the balance of naval forces in the Black Sea between Russia and Turkey, which opposed it, changed in favor of the former. Writer Anatoly Elkin Fr. The dreadnought's displacement was determined to be 23,600 tons. The ship's speed is 22 3/4 knots, in other words, 22 3/4 nautical miles per hour, or about 40 kilometers. In one go, the Empress Maria could take 1970 tons of coal and 600 tons of oil. All this fuel for the Empress Maria was enough for an eight-day voyage at a speed of 18 knots. The ship's crew is 1260 people including officers. The ship had six dynamos: four of them were combat and two were auxiliary. It housed turbine machines with a capacity of 10,000 horsepower each. To power the turret mechanisms, each turret had 22 electric motors... Four three-gun turrets housed twelve Obukhov twelve-inch guns. The deck was completely freed from superstructures, which greatly expanded the sectors of fire for the main caliber turrets.

The Maria's armament was supplemented by thirty-two more guns for various purposes: mine and anti-aircraft. In addition to them, underwater torpedo tubes were installed. The armor belt, almost a quarter of a meter thick, ran along the entire side of the battleship, and on top of the citadel was covered with a thick armored deck. In a word, it was a multi-gun, high-speed armored fortress. Even in our time, in the era of aircraft carriers, missile cruisers and nuclear submarines, such a ship could be included in the combat formation of any fleet.”1

The battleship "Empress Maria" was a favorite of the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, Admiral Kolchak, because its presentation to the fleet began not with the ritually ceremonial tour of the ships anchored in the middle of the Northern Bay, but with an emergency departure to sea on the "Empress Maria" to intercept the German cruiser "Breslau", which left the Bosphorus and fired at the Caucasian coast. Kolchak made the Empress Maria his flagship and systematically went to sea on it. Telegram from A.V. Kolchak to Tsar Nicholas II dated October 7, 1916, 8 hours 45 minutes: “To Your Imperial Majesty I most humbly report: “Today at 7 o’clock. 17 min. On the roadstead of Sevastopol, the battleship "Empress Maria" was lost. At 6 o'clock. 20 minutes. An internal explosion occurred in the bow magazines and an oil fire started. The remaining cellars immediately began to flood, but some could not be entered due to the fire. Explosions of cellars and oil continued, the ship gradually landed with its nose and at 7 o'clock. 17 min. overturned. There are many rescued, their number is being clarified. Kolchak."

Telegram from Nicholas II to Kolchak October 7, 1916 11 hours 30 minutes: “I mourn the heavy loss, but I am firmly convinced that you and the valiant Black Sea Fleet will bravely endure this test. Nikolai." Telegram from A.V. Kolchak to the Chief of the General Naval Staff, Admiral A.I. Rusin: Secret No. 8997 October 7, 1916 “It has been established so far that the explosion of the bow magazine was preceded by a fire that lasted approx. 2 minutes. The explosion moved the bow turret. The conning tower, the forward mast and the chimney were blown into the air, the upper deck up to the second tower was opened. The fire spread to the cellars of the second tower, but was extinguished. Following a series of explosions, up to 25 in number, the entire bow section was destroyed. After the last strong explosion, approx. 7 o'clock 10 minutes, the ship began to list to starboard and at 7 o'clock. 17 min. turned over with its keel up at a depth of 8.5 fathoms. After the first explosion, the lighting immediately stopped and the pumps could not be started due to broken pipelines. The fire occurred 20 minutes later. After the team was awakened, no work was carried out in the cellars. It was established that the cause of the explosion was the ignition of gunpowder in the forward 12th magazine, and shell explosions were a consequence. The main reason can only be either spontaneous combustion of gunpowder or malicious intent. The commander was saved, mechanical engineer midshipman Ignatiev died from the officer corps, 320 lower ranks died. Being personally present on the ship, I testify that its personnel did everything possible to save the ship. The investigation is carried out by a commission. Kolchak"

From a letter from A.V. Kolchak I.K. Grigorovich (not earlier than October 7, 1916): “Your Excellency, dear Ivan Konstantinovich. Let me express to you my deep gratitude for the attention and moral assistance that you provided me in your letter dated October 7th. My personal grief over the best ship of the Black Sea Fleet is so great that at times I doubted my ability to cope with it. I have always thought about the possibility of losing a ship at sea in wartime and am prepared for this, but the situation of the death of a ship in a roadstead and in such a final form is truly terrible. The hardest thing that remains now, and probably for a long time, if not forever, is that no one knows the real reasons for the death of the ship and everything comes down to mere assumptions. The best thing would be if it were possible to establish malicious intent - at least it would be clear what should be foreseen, but there is no such certainty and no indications of this exist. Your wishes regarding the personnel of the “Empress Maria” will be fulfilled, but let me express my opinion that a trial would be desirable now, because subsequently it will lose a significant share of its educational significance..."1 They tried to unravel the cause of the explosion of the battleship "Empress Maria" in the Sevastopol roadstead without delay, but there is still no clear opinion - whether it was a tragic accident or whether it was a daring sabotage... Remember how in Rybakov’s story “Dirk,” one of its heroes, Polyakov, said: “A dark story, it didn’t explode on a mine, not from a torpedo, but by itself...”.

So what are the versions of what happened? Firstly, there may have been spontaneous combustion of the gunpowder. In particular, in his testimony after his arrest, in January 1920, Admiral Kolchak believed that the fire could have occurred from self-decomposition of gunpowder caused by violations of production technology under wartime conditions. He also considered some kind of carelessness possible. “In any case, there was no evidence that there was any malicious intent,” he repeated his opinion. However, many experts reject this version as untenable. Spontaneous combustion could not have occurred, since the entire process of manufacturing and analyzing gunpowder at that time did not allow this. Every small change was carefully recorded, and each batch of gunpowder passed all legal tests.

Secondly, perhaps it was a failure to comply with safety measures when handling shells. For example, the former senior officer of the Empress Maria, Anatoly Gorodynsky, wrote in the Marine Collection, which was published in Prague in 1928, that, in his opinion, the battleship died due to careless handling of ammunition. In his article, he recalls that “senior commander Voronov went down to the cellar to record the temperature and, seeing the half-charges that had not been removed, decided not to bother the “guys” but to remove them himself. For some reason, he dropped one of them...” One of the survivors at the time of the explosions on the Empress Maria was the commander of the main caliber turret, midshipman Vladimir Uspensky, who was the watch commander on that tragic day, in his notes on the possible causes of the death of the battleship on the pages “Bulletin of the Society of Officers of the Russian Imperial Navy” writes: “The battleship “Empress Maria” was designed and laid down before the First World War. Numerous electric motors for it were ordered from German factories. The outbreak of war created difficult conditions for the completion of the ship. Unfortunately, those that were found were much larger in size, and it was necessary to carve out the necessary area at the expense of living quarters. The crew had nowhere to live, and contrary to all regulations, the servants of the 12-inch guns lived in the towers themselves. The combat stock of the three turret guns consisted of 300 high-explosive and armor-piercing shells and 600 half-charges of smokeless powder. Our gunpowder was exceptionally durable, and there was no question of any spontaneous combustion. The assumption about the heating of gunpowder from steam pipelines and the possibility of an electrical short circuit is completely unfounded. Communications took place outside and did not pose the slightest danger. It is known that the battleship entered service with imperfections. Therefore, until his death, there were port and factory workers on board. Their work was supervised by lieutenant engineer S. Shaposhnikov, with whom I had friendly relations. He knew the “Empress Maria,” as they say, from keel to keel and told me about numerous retreats and all sorts of technical difficulties associated with the war. Two years after the tragedy, when the battleship was already in dock, Shaposhnikov discovered a strange find in the turret room of one of the towers, which led us to interesting thoughts. A sailor's chest was found, in which there were two stearin candles, one started, the other half burnt, a box of matches, or rather what was left of it after two years in the water, a set of shoemaking tools, as well as two pairs of boots, one of which was repaired , and the other is not finished. What we saw, instead of the usual leather sole, amazed us: the owner of the chest had nailed cut strips of smokeless gunpowder, taken from half-charges for 12-inch guns, to the boots! Several such strips lay nearby. In order to have powder strips and hide the chest in the tower room, one had to belong to the tower servants. So, perhaps, such a shoemaker lived in the first tower? Then the picture of the fire becomes clearer. To get the belt powder, you had to open the lid of the pencil case, cut the silk cover and pull out the plate. Gunpowder, which had lain for a year and a half in a hermetically sealed case, could release some ethereal vapors that flared up from a nearby candle. The ignited gas ignited the case and gunpowder. In an open pencil case, the gunpowder could not explode - it caught fire, and this combustion continued, perhaps, for half a minute or a little more, until it reached the critical combustion temperature - 1200 degrees. The combustion of four pounds of gunpowder in a relatively small room caused, without a doubt, the explosion of the remaining 599 pencil cases. Unfortunately, the civil war and then the departure from Crimea separated Shaposhnikov and me. But what I saw with my own eyes, what we assumed with the lieutenant engineer, couldn’t it serve as another version of the death of the battleship “Empress Maria”?”1

Thirdly, perhaps this was an act of sabotage with the aim of inflicting losses and weakening the power of Russia. According to the marine painter Anatoly Elkin, the explosion on the battleship Empress Maria was prepared by German agents who had settled before the war in Nikolaev, where the dreadnought was being built. His arguments are presented quite harmoniously and convincingly in The Arbat Tale, which was published as a separate book. In his book “Secrets of Lost Ships,” Nikolai Cherkashin provides some pretty interesting information. “In the magazine “Marine Notes”, published in New York by the Society of Former Officers of the Imperial Navy, in the 1961 issue, I found an interesting note signed as follows: “Captain 2nd Rank V.R. reported.” “..The disaster is still inexplicable - the death of the battleship Empress Maria. The fires at a number of coal mines on the way from America to Europe were also inexplicable, until the cause was determined by British intelligence. They were called by German “cigars”, which the Germans, who obviously had their own agents who penetrated among the loaders, managed to plant during loading. This cigar-shaped diabolical device contained both fuel and an igniter, ignited by current from an electrical element, which came into action as soon as the acid corroded the metal membrane that blocked access to the acid of the element. Depending on the thickness of the plate, this happened several hours or even several days after the “cigar” was installed and tossed. I haven't seen a blueprint for this damn toy. I only remember what was said about a stream of flame coming out of the tip of the “cigar,” in the manner of a Bunsen burner. One “cigar” placed “sensibly” in the turret compartment was enough to burn through the copper shell of a half-charge. Factory craftsmen worked at “Maria”, but, presumably, the inspection and control were not up to par... So the thought of a German “cigar” drilled my brain... And I’m not the only one. 15-20 years after this memorable day, I had to collaborate in a business with a German, a nice man. Over a bottle of wine we reminisced about the old times, the times when we were enemies. He was a Uhlan captain and in the middle of the war was seriously wounded, after which he became incapable of combat service and worked at headquarters in Berlin. Word by word, he told me about an interesting meeting. “Do you know the one who just left here?” - a colleague once asked him. "No. And what?" - “This is a wonderful person! This is the one who organized the explosion of a Russian battleship in the Sevastopol roadstead.” “I,” my interlocutor answered, “heard about this explosion, but did not know that it was the work of our hands.” "Yes it is. But this is very secret, and never talk about what you heard from me. This is a hero and patriot! He lived in Sevastopol, and no one suspected that he was not Russian...” Yes, for me after that conversation there are no more doubts. “Maria” died from a German “cigar”! More than one “Maria” died in that war from an inexplicable explosion. The Italian battleship Leonardo da Vinci also died, if my memory serves me correctly.”1 The famous researcher Konstantin Puzyrevsky writes that in November 1916, Italian counterintelligence after the explosion in August 1915 in the harbor of the main base of the Italian fleet Taranto of the battleship Leonardo da Vinci ", attacked "the trail of a large German espionage organization, headed by a prominent employee of the papal chancellery, who was in charge of the papal wardrobe. A large amount of incriminating material was collected, from which it became known that espionage organizations carried out explosions on ships using special devices with clockwork mechanisms with the expectation of producing a series of explosions in different parts of the ship in a very short period of time in order to complicate fire extinguishing ... "1 B In his book “Fleet,” Captain 2nd Rank Lukin also writes about these tubes: “In the summer of 1917, a secret agent delivered several small metal tubes to our Naval General Staff. They were found among the accessories and lace silk underwear of a charming creature... Miniature tubes - “trinkets” were sent to the laboratory. They turned out to be extremely fine chemical fuses made of brass. It turned out that exactly these tubes were found on the mysteriously exploded Italian dreadnought Leonardo da Vinci. One did not ignite in a cap in the bomb cellar. Here is what an officer of the Italian naval headquarters, Captain 2nd Rank Luigi di Sambui, said about this: “The investigation undoubtedly established the existence of some secret organization for blowing up ships. Its threads led to the Swiss border. But there their trace was lost. Then it was decided to turn to the powerful thieves organization - the Sicilian mafia. She took up this matter and sent a fighting squad of the most experienced and determined people to Switzerland. A lot of time passed until the squad, through considerable expenditure of money and energy, finally found the trail. It led to Bern, to the dungeon of a rich mansion. Here was the main storage facility of the headquarters of this mysterious organization - an armored, hermetically sealed chamber filled with asphyxiating gases. There is a safe in it... The mafia was ordered to enter the cell and seize the safe. After long observation and preparation, the squad cut through the armor plate at night. Wearing gas masks, she entered the cell, but because she was unable to capture the safe, she blew it up. A whole warehouse of tubes ended up in it.”1 Captain 1st Rank Oktyabr Petrovich Bar-Biryukov served in the 1950s on the Soviet battleship Novorossiysk, which repeated the tragedy of its predecessor, the dreadnought Empress Maria, in the same ill-fated Northern Bay. For many years he investigated the circumstances of both disasters. Here is what he was able to establish in the “Maria” case: “After the Great Patriotic War, researchers who managed to get to documents from the KGB archives identified and made public information about work in Nikolaev since 1907 (including at a shipyard that built Russian battleships) a group of German spies led by resident Werman. It included many well-known people in this city and even the mayor of Nikolaev, Matveev, and most importantly, shipyard engineers: Sheffer, Linke, Feoktistov and others, in addition, electrical engineer Sgibnev, who studied in Germany. This was revealed by the OGPU in the early thirties, when its members were arrested and during the investigation testified about their participation in the bombing of “I. M.”, for which, according to this information, the direct perpetrators of the action - Feoktistov and Sgibnev - were promised 80 thousand rubles in gold by Verman each, however, after the end of hostilities... Our security officers were of little interest in all this then - cases from pre-revolutionary prescription were considered no more than a historically curious “texture”. And therefore, during the investigation of the current “sabotage” activities of this group, information about the bombing of “I. M." did not receive further development. Not long ago, employees of the Central Archive of the FSB of Russia A. Cherepkov and A. Shishkin, having found part of the investigative materials in the case of the Verman group, documented the fact of the exposure in 1933 in Nikolaev of a deeply secret network of intelligence officers working for Germany, operating there since pre-war times and “ focused" on local shipyards. True, they did not find specific evidence of the group’s participation in the bombing of I.G. in the initially discovered archival documents. M.”, but the contents of some protocols of interrogations of members of Verman’s group even then gave quite strong reasons to believe that this espionage organization, which had great capabilities, could well have carried out such sabotage. After all, it was unlikely that she “sat idly by” during the war: for Germany it was extremely necessary to disable the new Russian battleships on the Black Sea, which posed a mortal threat to the Goeben and Breslau. Recently, the above-mentioned employees of the Central Election Commission of the FSB of the Russian Federation, having continued the search and study of materials related to the case of the Verman group, found in the archival documents they found of the OGPU of Ukraine for 1933-1934 and the Sevastopol Gendarmerie Directorate for October - November 1916 new facts that significantly complement the -revealing a new “sabotage” version of the reason for the explosion of “I. M." Thus, interrogation reports indicate that a native (1883) of the city of Kherson - the son of a native of Germany, steamboatman E. Werman - Viktor Eduardovich Werman, educated in Germany and Switzerland, a successful businessman, and then a shipbuilding engineer, was indeed a German intelligence officer with pre-revolutionary times (the activities of V. Verman are described in detail in that part of the archival investigative file of the OGPU of Ukraine for 1933, which is called “My espionage activities in favor of Germany under the tsarist government”). During interrogations, he testified, in particular: “...I began to engage in espionage work in 1908 in Nikolaev (it was from this period that the implementation of a new shipbuilding program in the south of Russia began. - O.B.), working in the department of marine machinery. I was involved in espionage activities by a group of German engineers from that department, consisting of engineer Moor and Hahn.” And further: “Moor and Hahn, and most of all the first, began to process and involve me in intelligence work in favor of Germany...” After Hahn and Moor left for Germany, the “management” of Wermann’s work passed directly to the German vice-consul in Nikolaev, Mr. Winstein. Werman, in his testimony, gave comprehensive information about him: “I learned that Winstein is an officer in the German army with the rank of Hauptmann (captain), that he is in Russia not by chance, but is a resident of the German General Staff and carries out extensive intelligence work in the south of Russia. Around 1908, Vinstein became vice-consul in Nikolaev. He fled to Germany a few days before the declaration of war - in July 1914.” Due to the prevailing circumstances, Woerman was tasked with taking over the leadership of the entire German intelligence network in southern Russia: Nikolaev, Odessa, Kherson and Sevastopol. Together with his agents, he recruited people there for intelligence work (many Russified German colonists then lived in the south of Ukraine), collected materials on industrial enterprises, data on surface and submarine military vessels under construction, their design, armament, tonnage, speed and etc. During interrogations, Werman said: “... Of the people I personally recruited for espionage work in the period 1908-1914, I remember the following: Steiwech, Blimke... Linke Bruno, engineer Schaeffer... electrician Sgibnev” (I brought him together with the latter in 1910, the German consul in Nikolaev Frischen, who chose the experienced electrical engineer Sgibnev, a money-hungry workshop owner, with his trained intelligence eye as a necessary figure in the “big game” he had started. All those recruited were or, like Sgibnev, became (he was on the instructions of Werman from 1911 he went to work at Russud) as employees of shipyards who had the right of passage to the ships being built there. Sgibnev was responsible for work on electrical equipment on warships built by Russud, including the Empress Maria. In 1933, during the investigation, Sgibnev testified that Werman was very interested in the electrical design of the main-caliber artillery towers on the new Dreadnought-class battleships, especially on the first of them transferred to the fleet, the Empress Maria. “During the period 1912-1914,” said Sgibnev, “I conveyed various information to Verman about the progress of their construction and the timing of the readiness of individual compartments - within the framework of what I knew.” The special interest of German intelligence in the electrical circuits of the main caliber artillery turrets of these battleships becomes understandable: after all, the first strange explosion on the Empress Maria occurred precisely under its bow main caliber artillery turret, all the premises of which were saturated with various electrical equipment... In 1918, after the German occupation of the South In Russia, Verman's intelligence activities were duly rewarded. From the protocol of his interrogation: “...According to the proposal of Lieutenant Commander Kloss, I was awarded the Iron Cross, 2nd degree, by the German command for selfless work and espionage activities in favor of Germany.” Having survived the intervention and the Civil War, Verman settled in Nikolaev. Thus, the explosion at I. M.”, despite Werner’s deportation during this period, was most likely carried out according to his plan. After all, not only in Nikolaev, but also in Sevastopol, he prepared a network of agents. During interrogations in 1933, he spoke about it this way: “...I personally have been in contact since 1908 on intelligence work with the following cities: ...Sevastopol, where intelligence activities were led by mechanical engineer Vizer, who was in Sevastopol on behalf of our plant specifically for the installation of the completed construction in Sevastopol the battleship "Zlatoust". I know that Vizer had his own spy network there, of which I remember only the designer of the Admiralty, Ivan Karpov; I had to deal with him personally.” In this regard, the question arises: did Wieser’s people (and he himself) participate in the work on the Maria in early October 1916? After all, at that time there were shipbuilding workers on board every day, among whom they could well have been. This is what is said about this in the report dated 10/14/16 from the head of the Sevastopol gendarme department to the chief of staff of the Black Sea Fleet (recently identified by researchers). It provides information from secret gendarmerie agents on I. M.”: “The sailors say that the electricity wiring workers, who were on the ship before the explosion until 10 o’clock in the evening, could have done something with malicious intent, since the workers did not look around at all when entering the ship and also worked without inspection. Suspicion in this regard is especially expressed against an engineer from the company at 355 Nakhimovsky Prospekt, who supposedly left Sevastopol on the eve of the explosion... And the explosion could have occurred from an incorrect connection of electrical wires, since before the fire the electricity on the ship went out..." (true a sign of a short circuit in the electrical network. - O.B.). The fact that the construction of the newest battleships of the Black Sea Fleet was carefully “guarded” by agents of German military intelligence is also evidenced by other recently discovered documents.”1 Immediately after the disaster, a commission of the Maritime Ministry, which arrived from Petrograd, was created to clarify its causes. It was headed by a member of the Admiralty Council, Admiral N.M. Yakovlev. A general was appointed a member of the commission and the chief expert on shipbuilding for special assignments under the Minister of the Navy, Lieutenant General of the Navy, full member of the Academy of Sciences A.N. Krylov, who became the author of the conclusion, unanimously approved by all members of the commission. Of the three possible versions, the first two were spontaneous combustion of gunpowder and negligence of personnel in handling fire or powder charges, the commission did not, in principle, rule out. As for the third, even having established a number of violations in the rules of access to cellars and a lack of control over workers arriving on the ship (according to a long-standing military tradition, they were counted by head without checking documents), the commission considered the possibility of malicious intent to be unlikely... That's it...

As for the further fate of the battleship "Empress Maria", then in 1916, according to the project proposed by Alexei Nikolaevich Krylov, the lifting of the ship began. This was a very extraordinary event from the point of view of engineering art; quite a lot of attention was paid to it. According to the project, compressed air was supplied to the pre-sealed compartments of the ship, displacing water, and the ship was supposed to float upside down. Then it was planned to dock the ship and completely seal the hull, and put it on an even keel in deep water.

During a storm in November 1917, the ship surfaced with its stern, and completely surfaced in May 1918. All this time, divers worked in the compartments, unloading ammunition continued. Already at the dock, 130 mm artillery and a number of auxiliary mechanisms were removed from the ship.

In the conditions of the civil war and revolutionary devastation, the ship was never restored and in 1927 was dismantled for scrap metal... The sailors who died in the explosion of the battleship "Empress Maria", who died from wounds and burns in hospitals, were buried in Sevastopol (mostly on old Mikhailovskoe cemetery). Soon, in memory of the disaster and its victims, a memorial sign was erected on the boulevard of the Korabelnaya side of the city - the St. George Cross (according to some sources - bronze, according to others - stone from local white Inkerman stone). It survived even during the Great Patriotic War and stood in place until the early 1950s. And then it was demolished...5

Sources of information: 1. Cherkashin “Secrets of lost ships” 2. Wikipedia website 3. Melnikov “LK of the “Empress Maria” type” 4. Krylov “My memories” 5. Bar-Biryukov “Catastorfa, lost in time”

“It is not possible to come to an exact conclusion”

0

...Six minutes ago there was a powerful explosion on the battleship "Empress Maria"...

The sudden death of one of the most modern ships in the fleet at the height of the war is an extraordinary event. To find out the reasons for the death of the battleship, a commission of the Naval Ministry was appointed, headed by a member of the Admiralty Council, Admiral Yakovlev. Three main versions were put forward: spontaneous combustion of gunpowder; carelessness in handling fire or gunpowder; evil intent. The result of the commission’s work was the following conclusion: “It is not possible to come to an accurate and evidence-based conclusion; we only have to assess the likelihood of these assumptions by comparing the circumstances that emerged during the investigation.” Admiral Kolchak did not believe in sabotage. Four years later, answering questions from investigators shortly before the execution, he touched on the “Empress Maria” story, noting: “In any case, there was no evidence that this was malicious intent.” Kolchak, like many in the navy, believed that design flaws could have destroyed the battleship. The already mentioned high temperature in the artillery magazines could lead to a fire.

Bibliography[edit]

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, ed. (1985). Conway's Fighting Ships of the World: 1906–1921

. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5. - McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian and Soviet battleships

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-481-4. - Vinogradov, Sergei E. (1998). "The development of battleships in Russia from 1905 to 1917." Warship International

.

XXXV

(3): 267–290. ISSN 0043-0374. - Vinogradov, Sergei E. (1999). "The development of battleships in Russia from 1905 to 1917, chapter 2." Warship International

.

International Naval Research Organization. XXXVI

(2): 118–141. ISSN 0043-0374.

Negligence or malice?

0

On the bottom of the battleship Empress Maria, 1918.

There was no confidence in the discipline of the crew. After the ship was raised, according to a number of witnesses, a sailor's chest was found in the turret room of one of the towers, which contained two stearine candles, a box of matches, a set of shoemaking tools, as well as two pairs of boots, one of which was repaired and the other unfinished . Allegedly, a certain craftsman from among the sailors nailed cut strips of smokeless belt gunpowder, taken from half-charges for guns, to his boots. Such manipulations could cause a disaster. The senior officer of the Empress Maria, Anatoly Gorodynsky, suggested many years later that one of the crew members could have dropped the ammunition while rearranging the artillery magazine. The commander of the Black Sea Fleet, Kolchak himself, admitted that discipline on the ships was lame, and he also did not rule out an explosion due to negligence. The possibility of sabotage was also considered. The Sevastopol gendarme department and counterintelligence reported that there were persistent rumors among the sailors that this was an attempt on the life of the fleet commander. The sailors believed that people “with German surnames” who were part of the entourage of the previous commander of the Black Sea Fleet could have tried to “remove” Kolchak.

***

The beginning of the twentieth century was marked by previously incredible breakthroughs in technology. The amount of knowledge and scientific discoveries in one leap grew into the quality of the product produced: electricity, radio, internal combustion engine, assembly line, cinema, sound recording, airships and airplanes, cars and railways, ocean liners and submarines, household chemicals and new medicines were rapidly changing familiar world. The developing economy required raw materials and new markets. Competition stimulated the arms race, and the pace was such that new technology became obsolete already during production. This was especially true for the fleet. The newest battleship, laid down in 1902, turned out to be morally and technically obsolete within five years.

The constant race of technologies, the boldness of ideas and playing ahead came into conflict with the imperial conservatism of the systems, the rigidity of management and the general denseness and lack of education of the masses. This led to tragedies.

The case of the “Werman group”.

0

The case of the death of the battleship Empress Maria was investigated many years later by the Soviet intelligence services. In the 1930s, a German intelligence station led by Victor Verman was discovered in Nikolaev. The group was suspected of preparing sabotage at shipyards in order to disrupt the Soviet shipbuilding program. During the investigation, Werman said that he had been working for the Germans since 1908, and during the First World War he collected information about the newest Russian battleships, in particular, about the Empress Maria. OGPU investigators established that the German command considered the “Empress Maria” a serious threat to its plans and even entertained the idea of sabotage. However, it was not possible to establish whether sabotage actually took place. By court decision, Werman himself was simply expelled from the USSR - it is possible that the German resident was exchanged for someone else. However, the whole story about the “Verman group” is seriously questioned, and some consider the testimony of the detainees to be forced, obtained under torture. The hero of the story “Dirk” speaks about the explosion on the battleship: “A dark story... We looked into this matter a lot, but it was all to no avail.” Perhaps these words are accurate in the year of the 100th anniversary of the death of “Empress Maria”.

Footnotes [edit]

- McLaughlin, pp. 229–30

- McLaughlin, pp. 230-31

- McLaughlin, pp. 233, 235-36

- McLaughlin, page 228

- ↑

Gardiner and Gray, p. 303 - McLaughlin, page 237

- McLaughlin, pp. 229, 235-37

- McLaughlin, pp. 233-34

- "Russian 12" / 52 (30.5 cm) Sample 1907 305 mm / 52 (12 ") Sample 1907". Navweaps.com. January 10, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- McLaughlin, page 261

- "Russian 130 mm/55 (5.1″) Plan 1913". Navweaps.com. May 10, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ abc McLaughlin, page 234

- "Russian 75 mm / 50 (2.95″) Pattern 1892". Navweaps.com. July 17, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- "Russia/USSR 76.2 mm/30 (3") pattern 1914/15 "Gun Lender" (8-K)". Navweaps.com. November 21, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- McLaughlin, page 233

- Friedman, Norman (2008). Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Artillery in the Dreadnought Age

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 273–75. ISBN 978-1-59114-555-4. - ^ ab McLaughlin, pp. 234–35

- McLaughlin, pp. 231-33

- McLaughlin, pp. 231, 242, 304-06

- McLaughlin, pp. 242, 306-07

- McLaughlin, page 310

- McLaughlin, pp. 242, 308, 330-31

- Jump up

↑ McLaughlin, pp. 241, 308, 323 - Robbins, C.B.; Enqvist, Uwe T. (1995). "The guns of General Aleseev." Warship International

.

Toledo, OH: International Naval Research Organization. XXXII

(2): 185–92. ISSN 0043-0374.

Raised and dismantled for metal.

0

The battleship "Empress Maria" after docking, 1919.

Almost immediately after the death of the Empress Maria, development of a plan for raising the ship began. According to the project, compressed air was supplied to the pre-sealed compartments of the ship, displacing water, and the ship was supposed to float upside down. Then it was planned to dock the ship and completely seal the hull, and put it on an even keel in deep water.

0

The unique project was developed by Russian shipbuilder Alexei Krylov. This amazing man, a shipbuilder and mathematician, would later add the Stalin Prize and the title of Hero of Socialist Labor to his royal regalia.

0

Krylov's project was successfully implemented - in August 1919, the battleship's hull was docked. Alas, the Civil War did not allow us to complete what we started. As a result, in 1927, the never restored battleship was dismantled for metal.

0

The main caliber towers, which fell off the Empress Maria during the sinking, were raised by specialists from a special-purpose underwater expedition in 1931. Some researchers claim that the raised guns were introduced into the 30th coastal battery and participated in the defense of Sevastopol during the Great Patriotic War. Their opponents reject this assumption, stating that only gun mounts from the Russian battleship were used in the battery.

The death of the squadron battleship Jena

The first major disaster in Toulon associated with an explosion of ammunition occurred in March 1907 on the battleship Jena, which was in dry dock at that time.

The squadron battleship Iena was commissioned in April 1902. Compared to its predecessors, the Charlemagne-class battleships, it was heavier (displacing 12.1 thousand tons), longer (122.3 meters) and had better seaworthiness.

Squadron battleship "Iena" on a voyage

Image from the collection of Peter Kamenchenko

The main armament of the Jena consisted of four 305-mm guns, placed in pairs in turrets at the bow and stern. Each such weapon fired 349-kilogram armor-piercing shells at a distance of up to 12 kilometers with a frequency of one shot per minute. The ammunition capacity of each gun was 45 shells. There were also smaller caliber guns (8 x 164 mm, 8 x 100 mm, 16 x 47 mm) and four torpedo tubes.

The Jena was powered by three steam engines capable of accelerating the battleship to 18 knots (approximately 33 kilometers per hour). The cruising range was 4,500 nautical miles (more than 8 thousand kilometers). Team - 701 people. For its time it was a fairly powerful warship.

On March 4, Jena was put into dry dock for cleaning the underwater hull and ongoing repairs. By March 12, the battleship's cellar cooling system had been dismantled, but no one bothered to unload the ammunition ashore.

At about two o'clock in the morning, smoke poured out of the casemate of the stern 100-mm gun. It was impossible to flood a compartment of a ship in dry dock. The flames quickly spread to the cellar where 305 mm shells were stored.

The battleship Patri, standing in an open roadstead, trying to flood the dock and thereby prevent the spread of the fire, fired at the gate doors, but they survived. Midshipman de Vassy-Roucher managed to open the locks manually, but it was too late. A series of explosions followed, the most powerful of which turned the modern battleship into a pile of metal. The midshipman was killed by an armor plate flying off the hull, and the next-generation battleship Suffren, which was standing in a nearby water-filled dock, almost capsized from the impact of the shock wave. The result of the disaster was 118 killed, including civilians, and 35 wounded.

March 12, 1907. Explosion of the squadron battleship Iena at the dock of the Toulon naval base

Image from the collection of Peter Kamenchenko

"Jena" could not be restored and was withdrawn from the fleet. The skeleton of the battleship was used as a floating target when testing new 305-mm armor-piercing shells. The remains of the battleship's hull still lie rusting in the shallow waters off the island of Porquerolles between Marseille and Nice.

The investigation showed that the cause of the explosion of the battleship was the spontaneous combustion of nitrocellulose gunpowder, widely used on ships of the French fleet. “Gunpowder-V” is an unstable composition and decomposes over time. The inspection revealed that 80 percent of the gunpowder on the Jena was in a condition dangerous for use.

Notes

- [secrethistory.su/542-utrennie-vzryvy-v-severnoy-buhte-gibel-imperatricy-marii.html Morning explosions in the Northern Bay (Death of the “Empress Maria”) // Secrets of history]

- [yuvit.mylivepage.ru/blog/604/9006 1931 LK Tower Empress Maria]

- L. I. Amirkhanov.

Chapter 5. 305 mm conveyors. // [wunderwaffe.narod.ru/WeaponBook/RW/06.htm Naval guns on the railway]. - [jedi.kosnet.ru/ocean/history/body.htm Battleship "Empress Maria"]

- Bragin V.I.

Some historical information about naval railway gun mounts // [rufort.info/library/bragin/bragin.html Guns on rails]. - M. - 472 p. - Vinogradov, Sergey Evgenievich.

2 // “Empress Maria” - return from the depths. - St. Petersburg: Olga, 2002. - T. 2. - P. 88, 89. - 96 p. - (Russian dreadnoughts). — ISBN 5-86093-104-2. - [base13.glasnet.ru/text/imp/25.htm R. M. Melnikov, “Empress Maria” type LC]

- Krylov A. N.

[militera.lib.ru/memo/russian/krylov_an/index.html My memories]. - Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences, 1963. - Vinogradov, Sergey Evgenievich.

1 // Battleships of the "Empress Maria" type. - St. Petersburg: Olga, 2002. - P. 39. - 116 p. — ISBN 5-86093-104-2. - [militera.lib.ru/memo/german/kopp_g/index.html Koop G. On the battle cruiser "Goeben". - St. Petersburg: “Ships and Battles”, 2002.]

- Most likely, there is an error in this place, since according to other sources, more familiar with the lifting operation, these towers fell on their own.

- [kolchak.sitecity.ru/stext_1811040303.phtml V.G.

Handorin Admiral Kolchak: truth and myths. Chapter “Under the Polar Sky”] - Sergeyev-Tsensky S.

[webreading.ru/sci_/sci_history/sergey-sergeev-censkiy-utrenniy-vzriv-preobraghenie-rossii-7.html Morning explosion (Transformation of Russia - 7)]