From battleships to dreadnoughts

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, the development of the navies of the leading world powers proceeded at a truly rapid pace. Due to the fact that the design and construction of a battleship or large cruiser took several years, warships sometimes became obsolete even before entering service.

But even against this background, the appearance of the English Dreadnought made a real revolution in military shipbuilding. One day, all the battleships in the world, including the newest ones, became hopelessly and completely outdated.

The Dreadnought project not only put into practice the idea of “all-big-gun” (“only big guns”), long promoted by theorists. He also set a new speed standard for the ship of the main forces.

The newest battleships of those years and even the Michigan, the American brother of the Dreadnought, the construction of which, by the way, the Americans began before the British, developed a speed of 18–19 knots (33–35 km/h). The British, thanks to the use of steam turbines, achieved a speed of 21 knots (almost 39 km/h).

This meant that, being twice as strong as any old type battleship, the Dreadnought could easily catch up with it and destroy it. When meeting with an entire squadron of enemy battleships, he could just as easily break the distance and evade pursuit.

In order not to remain practically unarmed at sea, all maritime powers were forced to join the process of “dreadnoughtization” of their fleets. The Italians did not stand aside either.

As a matter of fact, they were one of the initiators of this process. Long before the appearance of the Dreadnought, shipbuilding engineer Vittorio Cuniberti proposed for consideration by his compatriots, and then by the British, a design for a ship that embodied the principle of “only big guns.”

The classic battleship with four large-caliber guns in the bow and stern turrets was completely devoid of medium-caliber artillery (152–203 mm), which had already become ineffective at the beginning of the 20th century. Instead, the new type of battleship received several more guns, the same as the bow and stern ones. As a result, the total number of main caliber guns increased to eight, ten and even twelve.

Links[edit]

- Bagnasco, Erminio and Grossman, Mark (1986). Regia Marina: Italian Battleships of World War II: An Illustrated History

. Missoula, MT: Illustrated Story Publishing. ISBN 0-933126-75-1. - Bargoni, Franco & Gay, Franco (1972). Corazzate classe Conte di Cavour

. Rome: Bizzarri. OCLC 34904733. - Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Fleet: A Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8. - Campbell, John (1985). Naval weapons of World War II

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4. - Cernuschi, Ernesto and O'Hara, Vincent P. (2010). "Taranto: The Raid and Aftermath." In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2010

. London: Conway. pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1. - Gardiner, Robert and Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's Fighting Ships of the World: 1906–1921

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5. - Giorgerini, Giorgio (1980). "Battleships of the Cavour and Duilio class." In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship IV

. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 267–79. ISBN 0-85177-205-6. - Green, Jack and Massignani, Alessandro (2004). The Black Prince and the Sea Devils: The Story of Valerio Borghese and the Elite Units of the Decima MAS

. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81311-4. - Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of the First World War

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4. - Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval weapons of the First World War

. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7. - Hoare, Peter (2005). Battleships. London: Lorenz Books. ISBN 0-7548-1407-6.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2007). Jordan, John (ed.). The death of the battleship "Novorossiysk"

. Warship 2007. London: Conway. pp. 139–52. ISBN 978-1-84486-041-8. - McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian and Soviet battleships

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-481-4. - O'Hara, Vincent P. (2008). "Action off Calabria and the myth of moral superiority." In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2008

. London: Conway. pp. 26–39. ISBN 978-1-84486-062-3. - Kotov, M.V. (2002). "Repair and modernization of former German and Italian ships in the Soviet Navy (1945-1955)". Typhoon

.

No. 02

(42). - Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio; and others. (December 2017). "Main Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part 4: Dreadnought Battleships." Warship International

.

LIV

(4): 307–343. ISSN 0043-0374. - Preston, Anthony (1972). Battleships of the First World War: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918

. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1. - Rover, Jurgen (2005). Chronology of War at Sea 1939–1945: A Naval History of the Second World War

(Third Revised Edition). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2. - Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships

. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0. - Stille, Mark (2011). Italian battleships of World War II

. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-831-2. - Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II

. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

"Giulio Cesare"

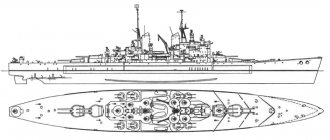

The Italians, who, according to the British, were much better at building ships than they were at fighting on them, decided to outdo everyone. They armed their first dreadnought with twelve, and the next three with thirteen 12-inch (305 mm) guns. One of the three battleships of the same type was named Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar).

© Photo from the archive of the Battleship Giulio Cesare.

The project was distinguished by its original artillery arrangement. Above the bow and stern three-gun turrets towered two more two-gun turrets. In the middle of the hull, between the chimneys, there was a third three-gun turret.

Thanks to this arrangement, the Giulio Cesare could fire on board from thirteen main-caliber guns, and five twelve-inch guns fired directly ahead and aft. This made the Italian battleship one of the strongest in the world at the time its construction began.

But while the Italians were building their battleships, more industrialized countries had already switched to the main caliber of 343, 356 and even 381 mm. Such ships began to be called “superdreadnoughts” (or “superdreadnoughts”).

At the beginning of the First World War, Giulio Cesare was no longer one of the most modern and powerful battleships. You could even say that it was morally obsolete as soon as it entered service.

The Italian battleship also had very significant design flaws. Thus, it turned out that even a single torpedo is capable of sending a battleship of this type to the bottom. That is, the mine protection system of “Giulio Cesare” and his brothers turned out to be incorrect in principle.

Without distinguishing itself in the First World War, Giulio Cesare was completely withdrawn from the fleet in 1928. She became a gunnery training ship. But when there was a smell of a new big war in Europe, the Italians thoroughly modernized the old ship and returned it to service.

After the modernization that took place in 1933–1937, the battleship changed significantly. The middle three-gun turret was dismantled. In place of its turret compartments, the mechanisms of the new power plant were placed. It was three times more powerful than the old one, thanks to which the ship’s maximum speed increased from 21.5 to 28 knots.

The bow of the battleship was lengthened by 10.3 meters, giving its hull new contours that made it possible to achieve the above increase in speed. The deck armor was strengthened and torpedo protection was improved.

The loss of three guns was partially compensated by increasing the caliber of the ten remaining ones (from 305 to 320 mm). In addition, by replacing the machines, they were given a larger maximum elevation angle, which increased the range of the guns.

All these measures brought “Giulio Cesare” in line with the requirements of the time, although, of course, they could not make it equal in power to the new Italian and foreign “classmates”. And the time of battleships itself was coming to an end. Aviation was already flying in to replace the heavy artillery.

In the Second World War, “Giulio Cesare” was noted for a slightly greater participation than in the First, but again did not accomplish any feats. He met the end of the war in the Sicilian port of Augusta.

© Photo from the archive

Battleship Giulio Cesare before transfer to the USSR.

Notes[edit]

- Battleship portal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giulio Cesare (ship, 1914) . |

- ↑

Sources disagree on whether

Giulio Cesare

a catapult or not.

Giorgerini says both ships received one; [9] Whitley, Bagnasco & Grossman and Bargoni & Gay say that only Conte di Cavour

received one. [10] [11] [12] - The German submarine U-596 claimed to have unsuccessfully attacked the ship in the Gulf of Taranto on 7 March 1944.[32]

With a new name

The Soviet Union, as the victorious power, had the legal right to some of the captured enemy equipment. The desire to receive in reparations at least one of the new Italian battleships of the Littorio type, armed with nine 15-inch (381 mm) guns, encountered the intransigence of the Western allies. By lot we only got the old man “Cesare”.

In December 1948, the battleship left Italy, and on February 3, 1949, its official transfer to the Soviet commission took place in the Albanian port of Vlora. There, on February 6, the Soviet naval flag was raised for the first time on the ship. The battleship arrived in Sevastopol on February 26. By order of the Black Sea Fleet dated March 5, 1949, the battleship was given the name Novorossiysk.

In Italy, the ship sat at the pier for a long time and did not undergo maintenance. His condition was depressing. The artillery and power plant, as well as the hull itself below the waterline, were in satisfactory condition. Everything else was neglected to the extreme. Some of the equipment was inoperative. The premises for the crew turned out to be unsuitable for living, they were not insulated, and there was no galley as such.

Particular difficulty during the repair was caused by the fact that the technical documentation was partly missing, and partly was in Italian. The translators did not have knowledge of special terms.

Despite all of the above, the command demanded that the battleship be brought into combat-ready condition within three months and go to sea on it to practice combat training missions. The ship was declared the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet.

According to the recollections of the commander of the ship’s hold group, “the squadron commander, Rear Admiral V.A. Parkhomenko, having become convinced of the impossibility of the task, gave the battleship’s officers a grand dressing down and then, in early August, he literally “pushed” the battleship into the sea. As part of the squadron, we approached the Turkish shores, waited for a NATO plane to appear, making sure that the Novorossiysk was floating, and returned to Sevastopol.”

After this, major repairs and modernization of the ship began, which lasted six long years. The Novorossiysk entered service with the Black Sea Fleet only in May 1955.

© Photo from the archive

Group photo of the Novorossiysk team.

Footnotes [edit]

- Giorgerini, page 269

- ^ ab Gardiner and Gray, page 259

- Giorgerini, pp. 270, 272

- Giorgerini, pp. 268, 272

- Chorus, page 175

- Giorgerini, pp. 268, 277-278

- Giorgerini, pp. 270-272

- McLaughlin, page 421

- ^ abc Giorgerini, page 277

- ^ abc Wheatley, page 158

- ^ abc Bagnasco and Grossman, page 64

- Bargoni & Gay, page 18

- Bargoni & Gay, page 19

- Brescia, page 58

- Jump up

↑ McLaughlin 2003, p. 422 - Bagnasco and Grossman, pp. 64-65

- Bagnasco & Grossman, page 65

- ^ ab Bargoni & Gay, page 21

- ^ ab McLaughlin 2003, pp. 421–22

- Silverstone, page 298

- Preston, page 176

- ^ a b Halpern, page 150

- ↑

Halpern, pp. 141–142 - Wheatley, pp. 158-61

- ↑

O'Hara, pp. 28–35 - Wheatley, page 161

- Cernushi & O'Hara, p. 81

- Wheatley, pp. 161-162

- Brescia, page 59

- ^ ab Wheatley, page 162

- Bargoni & Gay, page 71

- Rover, page 298

- Jump up

↑ Kotov, M (2002).

"Repair and modernization of former German and Italian ships by the Soviet Navy." Typhoon

.

2

:4. - Jump up

↑ McLaughlin 2003, pp. 419, 422 - ^ a b McLaughlin 2003, p. 423

- McLaughlin 2007, pp. 142-52

- ↑

Bar-Biryukov, October (October 24, 2005).

"Kill 'Caesar'" [Kill Caesar]. itorni

(43) . Retrieved March 20, 2014. - "Hugo D'Esposito: la Novorossiysk affondata nel '55 da incursori della Xa MAS" [Hugo D'Esposito: "Novorossiysk" was sunk in the '55 commando Xa MAS] (in Italian). 4Arts. July 25, 2013. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- Greene & Massignani, pp. 195-98

Catastrophe

On the evening of October 28, 1955, the flagship battleship returned to Sevastopol after one of the few training trips to sea. He was supposed to take part in celebrations dedicated to the anniversary of the defense of Sevastopol in the Crimean War. The ship took its designated place in the Northern Bay near the Naval Hospital, 110 meters from the shore.

An error occurred when mooring to the “battleship barrel”. The ship's commander was on vacation, and the senior mate performing his duties was not experienced enough and slipped the “barrel” by almost half the battleship's hull. They decided to fix the blot in the morning light...

But Novorossiysk was not destined to survive until the morning. At 1 hour 31 minutes on October 29, a powerful explosion was heard under the bow of the hull on the starboard side. Following it, almost simultaneously, another one thundered from the left side. A huge hole with an area of 150–160 square meters appeared in the right side. 8 decks, including 3 armored ones, were pierced by a giant cumulative jet rushing upward.

From 50 to 200 people (according to various estimates) sleeping in the forecastle quarters immediately died. The rest of the crew began to fight for the survivability of the ship. The acting commander and many other officers were on shore at the time of the explosion. Extra-conscripts were also released to the city. But the duty officers, foremen and ordinary sailors who remained on board began to do everything in their power to save the Novorossiysk.

In total, on this fateful night there should have been a little more than 1,200 people on the battleship, but on October 28, marines and cadets of naval schools arrived for further service. Together with them and emergency parties from other ships that arrived to help the flagship in distress, approximately 1,600 people were on board.

The XO and other officers soon returned to the ship on alert. Even earlier than them, an impressive “delegation” of naval ranks, consisting of seven admirals and twenty-eight senior officers, arrived on the Novorossiysk. They were headed by Parkhomenko. With the rank of vice admiral, he now commanded the entire Black Sea Fleet.

As is usually the case, the abundance of superiors only introduced additional confusion and confusion into the actions of the personnel. Even worse, Parkhomenko began to make “strong-willed decisions”, which to call simply erroneous would not be entirely correct.

First, he canceled the order given before his arrival to tow the battleship to the shore, where it could run aground and not sink. Then he sharply rejected the proposal to evacuate everyone who was not involved in the fight for the survivability of the ship. Moreover, this proposal was made several times, but each time Parkhomenko replied: “Stop panicking!” Instead of evacuation, the fleet commander ordered the team to line up on the poop and wait.

Only when the list to port and the trim to the bow became threatening did he allow towing to begin. But it was already too late! The bow of the battleship plunged into the water so deeply that it began to cling to the bottom, and the tugboats could not cope with the task.

© Photo from the archive

Battleship "Novorossiysk" before capsizing.

Subsequently, Parkhomenko justified himself by saying that the bottom was 17 meters away, and the width of the battleship was 28 meters, and he believed that even if it capsized on board, the Novorossiysk would partially remain above the water. The Vice Admiral, however, did not take into account that under the water column there was a 30-meter layer of viscous silt, and it was not hard enough to withstand the huge mass of the armored giant. Permission to evacuate was given only at the very last moment, when there was no time left for it.

At 4 hours 14 minutes the roll reached a critical level of 20 degrees. The battleship capsized on its left side, covering the people who fell into the water. Although there were lifeboats nearby, and the swim to the shore was a little more than a hundred meters, there were much fewer survivors and survivors than those who died in the explosion, drowned, crushed by the huge hull of the battleship and were fatally injured by mechanisms and anti-aircraft guns that fell from the tilting deck.

Many remained in the interior of the ship. They held on for a long time, hoping for salvation. Their knocks on the bulkheads were heard until the end of the day on November 1. But only 9 people were rescued: seven through a hole cut in the aft part of the bottom and two from under the poop deck, which was loosely adjacent to the ground.

According to the testimony of divers, the sailors dying inside the sunken battleship sang in chorus: “Our proud “Varyag” does not surrender to the enemy!

In total, in the Novorossiysk disaster, according to various sources, from 609 to 829 people died, and many more were wounded and maimed. Since it was not possible to save the ship, the list of those nominated for awards for courage and heroism during the struggle for survivability was not even considered by the top Soviet leadership. In 1999 alone, 716 members of the Novorossiysk team were awarded the Order of Courage, more than 600 of them posthumously.

Sabotage or negligence?

Expedition to the past: on the Yenisei they are looking for traces of sunken merchant ships

Researchers promise to post a map with their location on the Internet.

Admiral Kolchak did not believe in sabotage. But Naval Minister Grigorovich was sure of the opposite: “My personal opinion is that it was a malicious explosion using an infernal machine and that it was the work of our enemies. The success of their hellish crime was facilitated by the disorder on the ship, in which there were two keys to the cellars: one hung in the guard's closet, and the other was in the hands of the owner of the cellars, which is not only illegal, but also criminal. In addition, it turned out that at the request of the ship’s artillery officer and with the knowledge of its first commander, the plant in Nikolaev destroyed the hatch cover leading to the powder magazine. In such a situation, it is no wonder that one of the bribed persons, disguised as a sailor, and perhaps in a worker’s blouse, got on the ship and planted the infernal machine.

I don’t see any other reason for the explosion, and the investigation cannot reveal it, and everyone must go to trial. But since the Commander of the Fleet should also go on trial, I asked the Emperor to postpone it until the end of the war, and now to remove the ship’s commander from command of the ship and not give appointments to those officers who were involved in the unrest that had opened on the ship” (Quoted from: Grigorovich I.K. “Memoirs of the former Minister of the Navy”).

Battleship_7

Naval Minister of the Russian Empire Admiral Ivan Konstantinovich Grigorovich

Photo: commons.wikimedia.org

Work on raising the “Empress Maria” began back in 1916, but the Civil War did not allow it to be completed and the investigation to continue. In 1918, the ship's hull, which had floated under the pressure of air pumped into the compartments, was towed to the dock, drained, turned over, ammunition unloaded and weapons removed. The Soviet government planned to restore the battleship, but no funds were found. In 1927, the remains of the ship were sold for metal.

Over time, witnesses to the events on the Empress and participants in the investigation began to return to the tragic moments of October 20, 1916. Gradually, some other details began to be revealed that the members of the commission could not have known.

3D model of the cruiser "Varyag"

Battleship transformation

At the final stage of the war, the aircraft carrier forces of the Japanese Imperial Navy were practically exhausted (in the Battle of Midway alone, the Land of the Rising Sun lost four aircraft carriers). At the same time, no one doubted that it was carrier-based aviation that was becoming the dominant force in the war on the ocean. This realization led to a radical change in the fate of the third ship in the Yamoto-class series. From a planned battleship, she, now named Shinano, was rebuilt into a huge aircraft carrier. Considering the most radical changes to the entire structure of the huge ship, construction was greatly delayed. Nevertheless, on October 5, 1944, the new aircraft carrier was prepared for launching. However, while preparing to launch the Shinano, the gates of the dry dock in which it was being built were suddenly torn off, and a wave rushing into the dock hit the ship against the walls of the dock. The descent had to be postponed for three weeks. The Shinano, which was eventually launched, became the world's largest aircraft carrier. This record remained with him until 1960, when the first American nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Interprice went to sea. But the Japanese giant was not destined to live to see him.