West panics over Russian Baltic Fleet deployment of landing ships

Three large landing ships (LDC) of the Russian Navy left the Baltic Sea and headed for the Atlantic Ocean, before causing serious alarm in Sweden, which sent additional troops to the island of Gotland. This was reported by many Western media, at the same time linking the dispatch of the large landing craft with the situation of military tension on the Russian border with Ukraine. Translation of the main provisions of foreign publications is presented by discover24.ru.

“Russia’s military buildup along Ukraine’s borders is forcing the West to closely monitor the Kremlin’s every move, viewing everything from suspicious cyber hacks in Ukraine to the activation of armored units in distant Siberia and the deployment of Baltic Fleet landing ships as “preparing for an invasion.” notes the publication Maritime Executive.

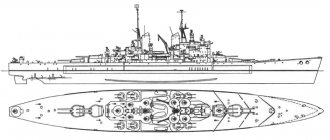

According to his information, three Ropucha-class landing ships (the NATO designation for the Project 775 BDK, built in Poland for the USSR Navy) “Kaliningrad”, “Korolev” and “Minsk” left the port of Baltiysk in the Kaliningrad region on January 15, and on Monday passed through the Danish Straits and headed into the Atlantic Ocean.

All three are usually assigned to the Baltic Fleet. Their final destination is unknown, but their movements are causing concern within NATO. The Ukrainian military expects an amphibious landing in Odessa in the event of a widespread Russian invasion, and three Ropuchas will add landing capabilities to the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Each of the Ropucha class ships is capable of carrying up to 12 amphibious armored personnel carriers and 340 troops or up to 10 main battle tanks. They are equipped with a bow ramp to allow direct landing on the beach, but can also operate in a landing mode from the open sea.

While maritime transits, including those involving Russian landing ships, to and from Kaliningrad are by no means uncommon, they have raised concerns in neighboring Sweden, which last week sent additional troops to the strategic island of Gotland in response to what it considered " deviating from the usual picture." Swedish military planners suggest that Gotland would be an ideal location for Russian air defense batteries in the event of war in the Baltic.

The commander of the Swedish armed forces, Lt. Gen. Michael Claesson, told the AP that a little earlier, three Northern Fleet landing ships left their home port on Russia's Kola Peninsula, sailed along the coast of Norway, and then entered the Baltic Sea on Jan. 12. During the passage, the ships were monitored by the Swedish Air Force, including the use of Gripen fighters. In addition to the landing ships, several Russian civilian vessels used to build the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline were relocated from the naval base in Kaliningrad to new positions - away from the pipeline route, but not far from Gotland.

The Drive portal clarifies that the transit of three Russian BDKs leaves in the Baltic two ships of the same class from the Northern Fleet - Olenegorsky Gornyak and Georgiy Pobedonosets, as well as the more modern BDK Project 11711 Petr Morgunov, which is capable of carrying up to 13 units armored vehicles and about 300 military personnel.

The Drive quoted Swedish Defense Minister Peter Hultqvist as saying: “An attack on Sweden cannot be ruled out. It is important to show that we will not be caught off guard and that we are taking this situation seriously.”

The current transfer of Ropucha-class ships may well be carried out to the Russian port of Tartus on the Mediterranean coast of Syria.

“In this case, they will almost certainly pass through the English Channel, which is a concern for the British military. In the past, Russian Navy warships passing along this route have always attracted close attention from both Royal Navy ships and Royal Air Force aircraft,” notes The Drive.

New in blogs

“February 22-23, 1940. Operation Wikinger. During the departure of the commander of the destroyers (F. Bonte) with the destroyers Leberecht Maas, Max Schultz, Richard Beitzen, Theodor Riedel. Erich Koellner and Friedrich Eckoldt in the Dogger Bank area against English trawlers, the formation was mistakenly attacked by German aircraft (the crews of the German aircraft were not informed that their own ships were in the area). Leberecht Maas was hit by three bombs. During an evasive maneuver, Leberecht Maas (Bassenge) and Max Schullz (Trampedach) entered one of two recently laid minefields by British destroyers in the passage between German minefields and were killed.” (Chronicle Marine Rundschau 1960 #1, p.49)

Descriptions of the Great Patriotic War often talk about the unsuccessful actions of the Soviet Navy during the war, especially at its beginning. The unorganized actions of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet led to the fact that a significant part of the fleet was cut off at the forward base. As a result, the tragedy of the “Tallinn Crossing” occurred. The very first raid of the Black Sea Fleet on Constanta led to the loss of the leader “Moscow”, and the enemy’s influence had nothing to do with it, in general.

Well, what about the fleets of other powers, how did they start the war? I think everyone knows that for the US Navy, the entry into the war was marked by Pearl Harbor, which is still considered a national disgrace. In principle, this fact can be explained (it is explained this way): “the insidious enemy suddenly and treacherously...”. And so on. Obviously, countries entering a war as the attacking party must be “okay” in this sense. The Japanese example is a “classic of the genre.” What about the Germans? But here – not everything is so simple! The war at sea did not begin triumphantly for Germany. Yes, the German fleet was significantly inferior to the English fleet! But the “right of passage” was with the Germans! They could choose the place and time of the strike. There were successes, of course. The battleship Royal Oak was sunk by a submarine at its base. The submarine is the aircraft carrier Coreyes. Another aircraft carrier, the Ark Royal, had the same fate. But he was “saved” by the unreliable torpedoes of a German submarine... But these were submariners’ successes, and even then they were more episodic than “systemic”.

The German surface fleet did not start the war with success. In principle, the Kriegsmarine was the first to “bleed” the English fleet. On November 23, 1939, the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sank the auxiliary cruiser Rawalpindi during their sortie. But the battle of two LCRs against a former postal and passenger ship, hastily equipped with 8 six-inch guns can hardly be called equal. And when “normal” cruisers appeared, the Germans for some reason did not engage in battle...

Burning Rawalpindi

In December, a very serious “answer” followed - after a battle in the South Atlantic with British cruisers, the “pocket battleship” Admiral Graf Spee “self-sank.” Moreover, to be honest, the forces of the British were by no means overwhelming...

And in February 1940, the event that is the subject of this article occurred. The German fleet tried to strike at the British trawlers, which were “either fishing or going on patrol.” The funny thing about this Viking operation (although the Germans clearly weren’t laughing!) was that the British didn’t even seem to know about this operation!

The German fleet carried out a classic “shadow boxing”. Moreover, he lost this battle, losing two modern destroyers and more than 500 people. The enemy at least fired at the Black Sea leaders...

The description of these events by the “monsters” of naval history (Roskill, Ruge) takes only 1-2 sentences. Therefore, let us turn to the detailed description published in the Breeze magazine.

The loss of two German destroyers Leberecht Maas (Z.1) and Max Schultz (Z.3) on February 22, 1940 is one of the most tragic events of the Second World War for the Germans. It is considered tragic - despite the fact that the loss of two destroyers is not such a rare event for a major war - because these two valuable ships for the German fleet, of which Germany had only twenty-two units, were lost as a result of the influence of their own armed forces.

In his book “War at Sea”, the famous German naval historian Friedrich Ruge noted on this occasion: ... the destroyers Leberecht Maas and Max Schultz were sunk by bombs dropped from their own aircraft, ... the notification of their return was delayed, following a winding path from one type of armed forces to another.

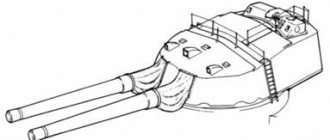

Destroyer Z1 "Leberecht Maas" From November 1939 to April 1940, the German Z-type destroyers were commanded by the head of the destroyers, Captain 1st Rank (later Commodore) Friedrich Bonte. The chief of the destroyers was the admiral or senior officer, who was in charge of the special combat training of all destroyers, regardless of what formations they belonged to. In cases where destroyers of different formations were brought together into one large group, the head of the destroyers took direct command over it. In the first months of the war, from October 17, 1939 to February 10, 1940, German destroyers, along with carrying out reconnaissance missions and sea surveillance, managed to lay nine mines along the passage routes of British ships off the east coast and laid about 1,800 mines. The first production took place on 17 October 1939 at the Humber Estuary, the next on 12 November at the Thames Estuary and the third on the night of 17/18 November again at the Humber Estuary. The number of mines laid was 540. During the next mine laying on December 6 in the Cromer area, German destroyers suddenly discovered two English destroyers, one of which (Jersey) was hit by a torpedo. The English formation apparently did not detect their enemy and assumed an attack by a German submarine. This opinion of the British Admiralty was strengthened by the deliberately false information in the report of the German armed forces. On the night of 12/13 December, five German destroyers laid mines at the mouth of the River Tyne. During the new moon in January 1940, the Germans laid minefields at Blyth, Cromer Knoll and the Thames Estuary in two operations. During the ninth mission on the night of 9/10 February 1940, the destroyers laid 157 mines off Cromer Knoll and another 110 mines in the Orfordness-Schipwash sea area. All barrage operations went unnoticed by the enemy. There were no losses on the German side. How skillfully these operations were carried out is shown by the remark of the British naval command, which testified that the English fleet did not resist, because it believed that in this area Germany was using only submarines and aircraft for minelaying. The North Sea has always been famous for fishing. Flotillas of many countries, and especially England, caught fish in its rich waters. Even during the war, British sailors sailed from east coast ports, continuing to supply the country with fresh fish. The most popular spot was Dogger Bank, a 90-mile-long sandbank in the southern North Sea. Luftwaffe aircraft on reconnaissance and bombing flights flying through this area always noted a concentration of fishing boats here. Information received by the headquarters of Naval Command West also spoke of suspicious behavior of some of these vessels, which could operate in conjunction with submarines. We remembered the times of the First World War, when, due to frequent attacks by German submarines on defenseless fishing vessels, some of them were adapted to tow a submarine, usually a small one (type S), which, if its towing vehicle was threatened, could itself send the attacking enemy to the bottom. However, such a course of events was unlikely for 1940, especially since after a few attacks by submarines, aviation began to pose the main threat to these ships. And during February 1940, German reconnaissance aircraft repeatedly discovered a large concentration of British fishing vessels at sea in the Dogger Bank area. These concentrations of ships prompted the naval command of the West (Admiral See Iwacher) to plan a destroyer operation against British trawlers in order to capture several valuable ships, force the British fleet to devote forces to the protection of the fishery, and thereby psychologically hurt the British and undermine their morale. The planned operation was initially codenamed “Kaviar”. and then "Vikings" (Wikinger). To carry out the operation, the 1st destroyer flotilla was allocated, under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Berger (Fregatten-capitan Fritz Berger). The flotilla consisted of six destroyers, each of which was assigned a prize crew. Z.1 Leberecht Maas - cap. 3rd rank Bassenge (Korvetten-kapitan Fritz Bassenge) Z.3 Max Schultz - cap. 3rd rank Trampedach (Korvetten-kapttan Klaus Trampedach) Z.4 Richard Beitzen - cap. 3rd Rank von Davidson (Korvetten-kapitan Hans von Davidson) Z.6 Theodor Riedel - cap. 3rd rank Bohmig (Korvetten-kapitan Gerhard Bohmig) Z.13 Erich Koellner - cap. 2nd Rank Fregatten-Kapitan Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs Z.16 Friedrich Eckoldt - Cap 2nd Rank Fregatten-Kapitan Schemmel The destroyers formed a strike group, and the Luftwaffe was to provide fighter cover and bomber support. Since the British fleet would hardly have had time to do anything during such a short exit, everyone preparing the operation was convinced that it was just going to be a cakewalk. Real events unfolded differently. The resumption of naval aviation reconnaissance on February 20, 1940 made it possible to determine the exact location and number of British trawlers. Based on this, the commander of the destroyers ordered Operation Wikinger to begin on February 22. The operational orders called for a surprise approach if possible to take the British by surprise, and it was necessary to capture the trawler; For his part, the Luftwaffe commander on February 22 received the task of reconnaissance of the Dogger Bank area and the sea areas to the south and west of it in order to protect the German formation from unpleasant surprises.

At 12.18, the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, to whom the X Air Corps (Lieutenant General Hans Geister), whose task included combat operations at sea, was directly subordinate, informed Naval Command West about an air operation against merchant shipping off the east coast of England also planned for 22 February. Channel to the maritime area south of the mouth of the Humber River. Air strikes were to be carried out by KG 26 (He 111). The appearance of aircraft in the combat area was expected no earlier than 19.30.

Already in the first half of the day, 13 aircraft took off to reconnaissance and attack ships off the east coast between the Orkney Islands and the Channel, but were forced to prematurely abandon the mission due to high clouds, or the complete absence of clouds that protected them from British fighters . The second report from X Air Corps to Naval Command West contained a request that the Kriegsmarine inform its subordinate air defense systems, which had been put on alert, that returning He 111 aircraft were possible in the evening hours. It would not hurt to briefly dwell on the relationship between the naval and air commands in North Sea combat areas. During the years of the creation of the Luftwaffe structure, the Kriegsmarine tried to obtain at its disposal naval aviation squadrons exclusively for use in combat operations at sea. However, Goering, commander of the German air force, did not allow this. The fleet, which expected the war much later than it actually happened, lost all hope of fulfilling its far-reaching plans to create its own air force with the outbreak of hostilities. At the outbreak of war, the Kriegsmarine had only eleven squadrons under Air Command West for use in the North Sea area. In total this amounted to 110 different aircraft, mostly seaplanes and naval reconnaissance aircraft. They could only be used for reconnaissance, security and mine laying. The Luftwaffe reserved the use of aviation in the war over the sea. For this purpose, on September 3, 1939, the X Aviation Division was formed as part of the II Air Fleet. Already on October 28, 1939, it was transformed into the X Aviation Corps, which was withdrawn from the II Air Fleet and transferred to the direct subordination of the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe. Both the naval and air commands lacked much to work effectively and purposefully together. For example, by the beginning of the war it was not possible to create a unified numbering of card squares, as well as common codes. We were in the process of creating the necessary lines of communication between command headquarters and formation headquarters. By the time Operation Wikinger began in the North Sea combat area, there was no common command authority uniting naval and air force forces in the war at sea against Britain. Moreover, the command levels of these armed forces constantly acted independently of each other. On February 22, at about 12 o'clock, under the cover of Bf 109 JG 1 fighters, the German destroyer flotilla left the Schilling roadstead and entered Jade Bay. Air reconnaissance aircraft, which had recently taken off in accordance with the plan of the air force commander, were forced to prematurely abort the flight due to thickening fog, and by 14:00 the reconnaissance and air cover aircraft turned back on course. By this time, the commander of the destroyers with the 1st flotilla was southwest of Heligoland and heading westerly. Soon, changing course to the west-northwest (300°), the destroyers approached the West wall barrier, through which they intended to pass along the trawled fairway No. 1. This channel, about 6 miles wide, was usually trawled by minesweepers of the 1st Flotilla, providing secret and safe passage for German ships into the North Sea. However, in February, the minesweeper flotilla did not have a full complement, many minesweepers were blocked by ice in the Baltic, and even more were under repair, so the naval command had only three M-type minesweepers and two destroyers at its disposal to maintain the fairways. At about 1700 on 22 February, Naval Command West informed X Air Corps that the German destroyers would return to Jade Bay in the morning hours of 23 February. The X Air Corps was asked to provide aircraft to meet and reliably guard the ships. Fighter cover, as with the departure of destroyers, was assigned to JG 1.

Ship maneuvering diagram A little later, at 17.35. X Air Corps asked Naval Command West whether the German destroyers were actually on their way. And only at that moment was the headquarters of the air corps informed that the formation of destroyers that night would pass through the minefield area to Dogger Bank. On this basis, aircraft attacks should not have been carried out on targets north of the latitude of the Terschelling lightship (Feuerschiff “Terschelltng”), south of latitude 55 and the eastern region declared dangerous by the British. By this time, between 1740 and 1818, a second group of KG 26, consisting of eight aircraft, had taken off from Neumunster to operate against English shipping between the mouth of the Thames and the Firth of the Firth. Naval Command West was notified of this. Meanwhile, Bonte's destroyers were already on the eastern side of the German minefields at latitude 53°55′ N and at 18.18 were heading north-west. Entering the minefield, at 19.00 the ships of the flotilla lined up in the wake of Friedrich Eckoldt, Richard Beitzen, Erich Koellner, Theodor Riedel, Max Schultz and Leberecht Maas. The destroyers sailed at a speed of 26 knots, with an interval of 200 meters, heading 300°. All the watchmen were at their posts, wrapped in raglans against the piercing cold. The weather was good, except for the low air temperature of course. A light southwesterly wind was blowing and there was a low sea fog, but the German sailors were worried about the full moon directly behind the stern, which made the destroyers very visible. The trip went quite well, but at 19.13 the signalmen on the Friedrich Eckoldt noticed a twin-engine plane flying at an altitude of 60 meters along the formation of ships, as if carefully identifying them. The wake was clearly visible in the moonlight, and the commander of the flotilla, frigate captain Berger, not knowing the intentions of the aircraft, ordered the speed to be reduced to 17 knots, hoping to hide the ships' traces to a minimum. At 19.21 the plane appeared again and an air raid alert was announced on the destroyers. As soon as the plane began a new flight, the destroyers Richard Beitzen and Erich Koellner opened fire with 20 mm machine guns. The plane responded and soon turned away from the connection. The first lieutenant from the destroyer Leberecht Maas identified it as German, and on the Erich Koellner as enemy. But, unfortunately for the Germans, the opening of fire by the destroyers convinced the plane that the ships were not German. 20 minutes later, at 19.43, the plane was discovered again - Leberecht Maas reported that it was approaching it from the stern, from the side of the moon. A minute later, the destroyer realized that they were under attack: the plane dropped two bombs on them. Leberecht Maas returned fire but missed. Meanwhile, it was bombed quite well - one bomb exploded between the bridge and the forward smokestack of the destroyer. He had to reverse and turn to the right, signaling for help. Friedrich Eckoldt approached Leberecht Maas, but they could not see any visible damage. Meanwhile, the remaining ships also began to turn back, but the flagship ordered them to withdraw, and he himself, remaining 500 meters from Leberecht Maas, began to prepare for towing. Suddenly, the anti-aircraft guns on the emergency destroyer opened fire again. She was attacked again and two bombs hit her stern and amidships. After the flash of the explosion, a column of fire and smoke rose into the air - the ship received a fatal blow. One of the bombs hit near the second chimney and, when the smoke cleared, the bow and stern of the broken destroyer, sticking out of the water, became visible in the moonlight.

Bomber He-111 - a threat to the Kriegsmarine destroyers

The sunken middle part of the ship rested on the shallow soil of the sandbank. At 19.58 the flagship ordered all ships to lower lifeboats to rescue people. Erich Koellner approached the wreckage, where people were struggling with death in the icy, oil-covered water, and began to throw off lifebelts and rafts. His motorboat was lowered and approached the starboard propeller outlet to help the survivors. The destroyers Richard Beitzen and Friedrich Eckoldt also lowered their lifeboats, while the Max Schultz and Theodor Riedel were ordered to provide anti-submarine defense by carefully cruising around the disaster site in search of submarines. At 20.02, aboard the destroyer Theodor Riedel heard a new explosion in the northwest, in the direction of which Mach Schultz was a thousand meters away. As soon as Theodor Riedel turned to help him, the acoustician reported: “Submarine, noise level 5 decibels, bearing 200° starboard.” Almost simultaneously, the servants of gun No. 1 reported sighting torpedo tracks. At 20.08, a series of four depth charges were dropped from the ship, one of which did not explode, but Theodor Riedel itself had only a low speed at that time. The three remaining bombs were enough for him to suffer serious damage - the gyrocompass, steering gear and all steering controls were disabled. The ship's commander, Corvette-Captain Bemig, ordered the bombing to stop and life belts to be put on due to the presence of a submarine and the destroyer's loss of maneuverability. Before the steering gear was repaired, manual steering was used.

Destroyer Z3 "Max Schultz"

Reports of submarines, depth charge explosions, a mysterious aircraft and a lack of understanding of the situation all combined to cause panic on other ships. Submarines and torpedo tracks were visible everywhere. Erich Koellner, due to depth charges dropped from Theodor Riedel, ordered his boats to return. The commander, mistakenly believing that the boat had already been raised, ordered the boat to be set in motion and the destroyer flew into it, drowning the unfortunate people in it.

Erich Koellner circled around and returned to the wreckage to make sure there were no people on it. Was everyone saved? If so, who? Is this even Maas? As soon as the bow of the destroyer Erich Koellner entered the floating debris, the bridge was told: “A torpedo is approaching, a submarine on the left.” Panic began again. It was 20.30 when the commander of the ship, frigate captain Schulz-Hinrichs, believing that he himself had seen the tracks of two torpedoes, ordered full speed and turn to the left, leaving helpless people behind the stern. He was about to ram the boat, when suddenly those on the bridge realized that in front of them was the bow end of the destroyer Leberecht Maas, sticking out of the water like a ghostly figure. It now became clear that two destroyers had been sunk, which was immediately reported to the flotilla flagship. At 20.30, the head of the destroyers reported to the headquarters of the West naval command about the loss of the destroyer Leberecht Maas. and at 21.02 he added to the message: “...the destroyer Schultz was also missing. Probably a submarine." West Command headquarters gave the destroyer commander the authority to terminate the operation. After this, the surviving ships were ordered to set course 120° and return to Wilhelmshaven at a speed of 17 knots. Already at 20.09, the remaining four ships began to retreat to the southeast. What happened? The formation of destroyers was moving at a speed of 17 knots on a course of 300° when Leberecht Maas reported at about 19.40 the detection of an aircraft following it. At 19.56 the ship received several bomb hits and sank after the explosion. A few minutes after the death of the ship, at about 20.05 Max Schultz was also sunk. When the survivors were counted, it turned out that they were all from Leberecht Maas, and there were only 60 of them out of a crew of 330 people (24 on board Erich Koellner, 19 on Friedrich Eckoldt and 17 on Richard Beitzen). Of the 308 crew members of the Max Schultz, none were saved. “This ship carried its entire crew to the bottom of the sea. Cold water and lack of coordination in rescue efforts, which resulted from panic over submarine attacks, were the reason for such a high number of casualties." Operational report No. 172 of the headquarters of the naval command West dated February 23, 1940 (Department Ic of the headquarters of the Supreme High Command) reported on the morning of the same day about the participation of X Air Corps in the hostilities of the previous day. At about 6.18 pm, eight aircraft took off on a reconnaissance and attack mission between the Thames Estuary and the Firth of the Firth. Results: At about 20.00 an attack was made on a darkened moving armed steamer (from 3 to 4 thousand tons) abeam the Terschelling lighthouse. After the explosion, the ship caught fire and sank. The steamer fired anti-aircraft fire from one gun and several machine guns. Until now, the headquarters of Naval Command West believed that the death of the destroyers was caused by a mine or a torpedo from a submarine, but this was refuted after a brief report from the head of the destroyers, supplemented by a report from X Air Corps about the sad certainty of the relationship between the sinking of the ship by aircraft and the death of the destroyer. The aforementioned report from the commander of the destroyers had the following verbatim text: During Operation “Wikinger” on February 22 at about 19.50 in square 6954 (lower left), the aircraft tracking the ships was fired upon by the end ship. After the explosion they turned back: Leberecht Maas asked for help. After a new explosion, it broke in half and sank. This was soon followed by another explosion and a report from the destroyer Erich Koellner about the discovery of a submarine. At this moment, the absence of the destroyer Max Schultz was noticed. They left the dangerous area, interrupting the operation. 60 people rescued from the destroyer Leberecht Maas; the destroyer Erich Koellner was missing one person. What is striking is that the X Air Corps report speaks of an attack on only one target. Consequently, we cannot abandon the assumption that the Mach Schultz, when maneuvering while retreating from a dropped series of depth charges, could have been blown up by its own mines. Such a catastrophe required an explanation, but this was not easy to do, since the testimony of witnesses was contradictory. At first it was believed that the plane was British and sank both destroyers, but this answer was not satisfactory, since until now British planes had been unusually unsuccessful in attacks on ships. It was difficult to imagine that they could sink two ships at once in one night. In addition, the German aircraft on the Leberecht Maas destroyer was definitely identified. It was only after receiving a report from X Air Corps headquarters that one of its aircraft had attacked a ship heading 300° 20 miles north of the Terschelling lighthouse that a terrifying thought appeared at West Command headquarters.

Could the destroyers be sunk by their own planes? At first the idea was dismissed, but it continued to spread and the rumor reached Hitler. The Fuhrer immediately ordered the creation of a commission of representatives of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe to conduct a thorough investigation of the incident. During the inquest, which began on board the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper on February 23, 1940, surviving crew members from the destroyer Leberecht Maas, crews of other destroyers and aircraft were interviewed. After a long investigation, it was established that the He 111 aircraft from the 4th group of KG 26 made two bombing attacks, first sinking the destroyer Leberecht Maas, and then the Max Schultz. The aircraft was part of a force sent to attack merchant ships in the North Sea. The Lufftwaffe warned the naval headquarters about this operation, but the latter did not warn its destroyers. Moreover, the Kriegsmarine did not notify air headquarters that the destroyers had put to sea. In its conclusion, the commission found that the loss of both destroyers was “very likely” caused by 50 kg bombs from their own aircraft. The Chief of Naval Operations Staff, Vice Admiral Otto Schniwind, pointed this out in a report submitted to Hitler on March 15, 1940: The untimely warning of the X Air Corps about the planned destroyer operation contributed to the fatal development of events on the night of February 22/23. Even at noon, the assigned task of the combat use of X Air Corps should have prompted the headquarters of Naval Command West, through detailed negotiations, to come to a solution to all issues related to this peculiar night use of combat aviation forces. Obvious mistakes by Naval Command West headquarters led to the loss of both ships. But the most serious reasons must be sought in the incorrect organization of control in the North Sea combat area with their long, complicated route for passing orders.

As a result, no one was punished by the court-martial decision, but the incident further deepened the rift between the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine. However, without any doubt, the loss of the destroyers must be attributed to the ineffectiveness of the fleet. In the light of post-war information, the court's decision may be questioned, since, although there were no British submarines in the vicinity, in this area on the night of February 9-10, two British destroyers laid mines in the path of a German minesaw channel that had become known to British naval intelligence. Due to the lack of minesweepers in the German fleet, these mines could have caused the death of the destroyer Max Schultz after being attacked by an aircraft. There was speculation that since the destroyer Leberecht Maas was definitely sunk by bombs, Max Schultz could have been blown up by a mine, since the destroyers, disorganized after the first attack by the aircraft, could have fallen on enemy mines. Thus ended Operation Wikinger, in which German destroyers suffered their first losses of the war, while receiving great moral shock. In total, 579 officers and sailors died with the two ships. Due to the failure of this operation, subsequent attacks by German surface forces in the southern North Sea area were delayed until the start of Operation Weserubung, the invasion of Denmark and Norway, in which the Kriegsmarine lost ten more of its remaining twenty destroyers. Of the newly built ships in 1940, only three units of this class entered service. During the further course of the war, the Germans were able to achieve the presence of twenty-two destroyers in service only once, and even then for a very short period of time - in the second half of 1943.

Source of information: Muzhennikov V.B. "The destruction of the destroyers Z1 and Z3." Breeze - 1996. - No. 6.

Instead of a conclusion.

As we can see, one of the first Kriegsmarine operations led to losses caused by disorganization and panic that arose when the situation went beyond the “standard” framework.

The investigation into the loss of the Leberecht Maas and Max Schultz established that the culprit in their deaths was the He-111 aircraft, tail number 1H+IM, commanded by Feldwebel Jaeger from the 4th squadron of the 26th combat squadron. It so happened that the action of Berger’s ships coincided in time with the operation of the Xth Air Corps - a blow to British coastal shipping, and neither the aviators nor the sailors informed each other about their plans in a timely manner. The anti-aircraft fire from the destroyers confused the bomber pilots, who had no experience in identifying ships at sea, and led to an attack on their own ships.

Jäger is probably the most successful of the German pilots at sea - he has as many as two destroyers to his credit. Unfortunately, our own! True, there is also the “pilot of the thing” Rudel, who, according to his memoirs, blew up and sank everything that came his way...

By the way, a few hours later, at night, the German sailors “responded” to the pilots by mistakenly shooting down a He 111 from KGr 100.

After the war, a new circumstance emerged. From English documents it became known that on the night of February 10, 1940, two destroyers of the British 20th Flotilla laid a mine bank in the fairway of the Western Wall barrier. In the historical literature of the last two decades, the death of the Max Schultz is usually explained by a mine explosion, while the sinking of the Meuse is still attributed to the aircraft. It is curious that the “mine” version can already be traced in the reference book “Warships of the World” (New York, 1946).

Despite the demonstrative “insignificance” of the episode in the works of such authorities of naval history as Roskilde or Ruge, the German surface fleet practically ceased its activities before the start of the Norwegian campaign (April 1940). It is unlikely that such a pause was accidental.