- January 13, 2020

- Events

- Georgy Chernikov

The world has experienced many great wars, both short and very long. Within every military conflict there were events on the outcome of which a lot depended. However, it cannot be said that, despite all their importance, they remained in the memory of all people. In order to eliminate this historical injustice, let’s go back more than 140 years into the past and remember who the Russian soldiers fought with and what goals the Russian Empire set for itself.

The story of how Russia stood up for Bulgaria and Serbia

What kind of defense of the Shipka Pass was this and what kind of war was taking place at that time? To tie all the events together, let's move back to the end of April - beginning of May 1876, when the Bulgarian people attempted to free themselves from the yoke of the Ottoman Empire.

We are talking about the April Uprising, organized by members of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee. The Turks reacted to what was happening as harshly as possible: the riot claimed the lives of more than 30 thousand people, including civilians, and caused enormous discontent on the part of a number of European countries, and especially the Russian Empire, because mostly Orthodox people lived in Bulgaria. Many outstanding writers, politicians and other public figures, in particular Dmitry Mendeleev, Victor Hugo, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Otto von Bismarck, defended the Balkans.

If you delve deeper, you can come to the conclusion that the goal of the uprising was not even the overthrow of the Ottoman yoke, but the opportunity to give the event a wide resonance and receive military support from the “brother Slavs.” No wonder one of the leaders of the rebellion, Georgy Benkovsky, said that he had achieved his goal, inflicted a wound on the Ottoman Empire that could not heal, and also called on Russia to come.

Just a month later, the activity of the Balkan countries began to grow exponentially. Serbia and Montenegro, confident of help from the Russian Empire, declared war on Turkey. Many powers on the European stage continued to believe in a peaceful resolution of events, but, as in the case of Bulgaria, the Ottomans acted brutally and without hesitation. Having inflicted a series of devastating defeats, the Serbs asked for help. Several countries issued a joint ultimatum to the Muslim government, and the parties to the conflict concluded a truce for a period of 1 month. Turkey did not stop there and put forward conditions for concluding a peace treaty, the terms of which, naturally, did not suit Europe.

Creation of the Constantinople Conference

Attempts at a peaceful settlement of the Balkan conflict continued with renewed vigor on the part of Russia. However, parity with Austria-Hungary and Great Britain could not be achieved, and in the meantime the truce between Serbia and the Ottoman Empire came to an end, and the latter resumed their attacks. Every day the position of the Serbs became more complicated and had already become catastrophic, but at the end of October the Russian Empire put forward a new ultimatum to the Turks demanding that they conclude another truce, and otherwise promised to raise the weapons of individual army units. As a result, hostilities in the Balkans ceased again.

In December of the same 1876, a conference was organized in the Turkish capital, Constantinople, to end the armed conflict with Serbia and Montenegro. On the European side, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Austria-Hungary and the initiator of the negotiations, the Russian Empire, acted as a united front.

During the month that the meeting of political leaders of the seven powers lasted, the parties were unable to reach any agreements. In response to European proposals, the Ottoman Empire made counter-decisions that did not suit the former at all. The obvious stubbornness of the Turkish government completely freed Russia's hands in action: the states of the Old World were ready to take a neutral side in the event of a direct conflict between the empires. In fact, by its actions, the Muslim power was repealing the provisions of the Treaty of Paris twenty years ago, and it became obvious that a new war between the two powers was only a matter of time.

On April 24, 1877, the Russian Empire declared war on the Ottoman Empire.

Beginning of the Russian-Turkish War

According to the plan of domestic commanders, the conflict had to be resolved quickly. The head of state, Emperor Alexander II, understood that protracted actions would only work in favor of the Muslims, because the European powers would certainly not throw them into the net of the Russian army. The times of the power and greatness of the Ottomans have long passed; now it is a seriously ill country, which, during various military clashes, lost its influence in the territories it occupied. As a result, Europe understood that the Russian Empire would win the next war and, most importantly, would be able to take control of the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, providing itself with direct access to the Mediterranean Sea.

It is worth noting that throughout the war as a whole there was a certain inequality between the armies of the powers. In terms of the total number of troops, the Turks far outnumbered the Russians, but the latter were better trained in military affairs and had more professional experience. Also, the latter were supported by Serbs, Bulgarians, Montenegrins and many others - in a word, militias from various countries. Such unanimity of peoples strengthened the general morale. As for weapons, the picture was the opposite: the Ottomans were armed with the latest English and American rifles.

The very first stage of the offensive went entirely according to the plan of the Russian commanders. Having managed to agree with Romania on the entry of troops into the country, the army had to quickly cross the Danube River and occupy key positions in the area. The crossing took place near Zimchina (a city in the south of the modern country) and met virtually no resistance from the Turks.

After the operation, Russian troops began to split up in different directions. The first detachment, under the command of General Joseph Romeiko-Gurko, went to capture positions in the Stara Planina, the Bulgarian mountain system, the second, under the leadership of Alexander Romanov, the future Russian emperor, was supposed to capture the Rushchuk fortress. The third direction of the attack was the capture of the city of Nikopol, and the fourth group of troops was nothing more than a reserve.

The advance of the advanced forces continued at a rapid pace. At the end of June, the imperial army occupied the cities of Byala and Tarnov and came close to Nikopol. A few days later, this fortress was taken, but the hasty Turkish command, in fact, surrendered its position and redirected the battalions towards Plevna. And here the first problems of Russia began.

First siege of Plevna

A detachment under the leadership of General Yuri Schilder-Schuldner was sent to take the fortress, which was a key link in the road chain and was actually at the intersection of many directions, including the path to Sofia, Rushchuk and Lovche. Also, his detachment was supposed to connect with the group of Colonel Kleinhaus, but due to incorrect maps and poor intelligence, they not only did not meet, but moved even further away. The general ordered an attack on Plevna, but the city was already occupied by the Turks. In the first minutes of the battle, both sides opened artillery fire, then the Ottomans launched a counter-offensive, but the attempt to push back the Russian army was unsuccessful. Still without any information about the state of affairs of Colonel Kleinhaus, Schilder-Schuldner's regiments remained in their positions.

Meanwhile, the colonel sent several detachments to reconnaissance of the occupied city, but they failed to carry it out, just as they failed to occupy the village of Grivitsa. During the day, the commanders gathered forces in Sgalovets, but again, due to inconsistency of actions, many combat units did not immediately arrive at the gathering place.

The next day, both commanders began the assault on Plevna. Schilder-Schuldner's regiments advanced from the direction of Breslyanitsa, and Kleinhaus' army - from the village of Grivitsy. The main forces of the Turks were located slightly north of the city itself and, being at a height, had an excellent overview of both directions. Both groups of Russians, as before, were quite far from the group and did not have the opportunity to connect. Moreover, the column, which remained in position after the attempted siege the day before, had no options other than to advance in a straight line.

Early in the morning, Russian artillery opened fire on the right flank of the Turkish defensive positions. Having launched a rapid attack, Schilder-Schuldner's troops occupied the village of Bukovlek and controlled the road to Plevna. The reaction of the defenders did not take long: the Turks, having a large army, launched a counterattack, forcing the general to retreat, who never received the support of Colonel Kleinhaus. The latter, meanwhile, organized a new attack on the village of Grivitsa. The detachment came under artillery fire, but was able to occupy the village. The colonel died during the offensive, and in the evening the officer who replaced him, Sedletsky, began to advance from the direction of the village towards the defending Ottomans. The latter, in turn, fled to Plevna, and Colonel Sedletsky also retreated, because he had no idea how things were going with the Schilder-Schuldner detachments.

As a result, the first serious battle between the Turks and Russians brought nothing but human casualties. Due to poor reconnaissance and a command error in determining the size of the Ottoman army, the attack fizzled out, in fact, before it could proceed to a direct siege. Both sides lost over 2,000 people each.

New in blogs

Far from the Russian mother earth, here you fell for the honor of your dear fatherland, you took an oath of allegiance to Russia and remained faithful to the grave. You were not restrained by the formidable ramparts, the holy and right went into battle without fear. Sleep well, Russian eagles, Descendants honor and remember your glory... poems on one of the memorial plaques

135 years ago, Russian-Bulgarian troops won a victory near Shipka over the Turkish army of Vesil Pasha. At the beginning of 1878, the defense of Shipka was completed - one of the key and most famous episodes in the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878. The defense of Shipka pinned down significant forces of the Turkish army and provided the Russian troops with the shortest route of attack on Constantinople. Shipka became a shrine of Bulgarian patriots, since the Russian-Turkish War ended with the liberation of a significant part of Bulgaria from the Turkish yoke.

After crossing the Danube River and capturing bridgeheads, the Russian army could begin to implement the next stage of the offensive - the transition of Russian troops beyond the Balkan Mountains and a strike in the direction of Istanbul. The troops were divided into three detachments: Advanced, Eastern (Ruschuksky) and Western. The frontline - 10.5 thousand people, 32 guns under the command of Lieutenant General Joseph Vladimirovich Gurko, which included Bulgarian militias, was supposed to advance to Tarnovo, occupy the Shipka Pass, transfer part of the troops beyond the Balkan ridge, to Southern Bulgaria. The 45,000-strong Eastern and 35,000-strong Western detachments were supposed to provide the flanks.

Gurko's troops acted quickly: on June 25 (July 7) the Advance Detachment occupied the ancient Bulgarian capital - Tarnovo, and on July 2 (14) crossed the Balkan ridge through the inaccessible but unguarded Khainkoi Pass (located 30 km east of Shipka). The Russians went to the rear of the Turks, who were guarding Shipka. Gurko's troops defeated Turkish troops near the villages of Uflany and the city of Kazanlak and on July 5 (17) approached the Shipka Pass from the south. Shipka was defended by 5 thousand. Turkish garrison under the command of Hulussi Pasha. On the same day, the pass was attacked from the north by a detachment of General Nikolai Svyatopolk-Mirsky, but failed. On July 6, Gurko’s detachment from the south went on the offensive, but was also unsuccessful. However, Hulussi Pasha decided that the position of his troops was hopeless and on the night of July 6-7, he withdrew his troops along side roads to the city of Kalofer, abandoning the guns. Shipka was immediately occupied by the detachment of Svyatopolk-Mirsky. Thus, the task of the advance detachment was completed. The path to Southern Bulgaria was open, it was possible to advance on Constantinople. However, there were not sufficient forces for an offensive in the Trans-Balkan region; the main forces were tied up by the siege of Plevna, and there were no reserves. The initial insufficient strength of the Russian army had its effect.

Gurko's advance detachment was advanced to Nova Zagora and Stara Zagora. He was supposed to take positions at this line and close the approaches to the Shipka and Khainkoi passes. On July 11 (23), Russian troops liberated Stara Zagora, and on July 18 (30), Nova Zagora. However, soon 20 thousand troops transferred from Albania arrived here. corps of Suleiman Pasha, who was appointed commander of the Balkan army. Turkish troops immediately attacked, and on July 19 (31) a fierce battle took place near Stara Zagora. Russian soldiers and Bulgarian militias under the command of Nikolai Stoletov inflicted great damage on the enemy. But the forces were unequal, and the advance detachment was forced to retreat to the passes, where it became part of the troops of Lieutenant General Fyodor Radetsky (commander of the 8th Corps).

Fedor Fedorovich Radetsky.

Defense of Shipka

Shipka at that moment was part of the area of the southern front of the Russian army, which was entrusted to the protection of the troops of General Radetsky (8th, part of the 2nd corps, Bulgarian squads, about 40 thousand people in total). They were stretched over 130 versts, and the reserve was located near Tyrnov. In addition to protecting the passes, Radetzky’s troops had the task of securing the left flank against Plevna from Lovcha and the right flank of the Rushchuk detachment from Osman-Bazar and Slivno. The forces were scattered in separate detachments; on Shipka there were initially only about 4 thousand soldiers of the Southern detachment under the command of Major General Stoletov (half were left by the Bulgarians) against 60 camps (about 40 thousand) of the Turks of Suleiman Pasha. The Shipka Pass ran along a narrow spur of the main Balkan ridge, gradually rising to Mount St. Nicholas (the key to the Shipkinsky position), from where the road descended steeply into the Tundzhi valley. Parallel to this spur, separated from it by deep and partly wooded gorges, mountain ranges stretched from the east and west, which dominated the pass, but were connected to it only in 2-3 places by more or less passable paths. The position occupied by Russian troops was inaccessible, stretching several miles deep along an extremely narrow (25-30 fathoms) ridge, but could be subjected to crossfire from neighboring dominant heights. However, due to its strategic importance, the pass had to be held. The fortifications of the Shipka position included trenches in 2 tiers and 5 battery positions; rubble and wolf pits were built in the most important directions, and mines were laid. The process of equipping the positions was far from complete.

Shipka Pass.

The Turkish command, taking into account the important strategic importance of the pass, set the task for the troops of Suleiman Pasha to capture Shipka. Then Suleiman Pasha had to develop an offensive in a northern direction, connect with the main forces of the Turkish army, which were advancing on Rushchuk, Shumla and Silistria, defeat the Russian troops and throw them back across the Danube. On August 7, Suleiman Pasha's troops approached the village of Shipka. At this time, Radetzky, fearing that Turkish troops would pass into Northern Bulgaria through one of the eastern passes and strike at Tarnov, having received alarming messages about the strengthening of Turkish troops against our troops near the cities of Elena and Zlataritsa (later it turned out that the danger was exaggerated), 8 August sent a general reserve there. On August 8, Sulemyman Pasha concentrated 28 thousand soldiers and 36 guns against Russian troops on Shipka. Stoletov at that time had only about 4 thousand people: the Oryol infantry regiment and 5 Bulgarian squads with 27 guns.

On the morning of August 9, the Turks opened artillery fire, occupying Mount Maly Bedek, east of Shipka. This was followed by attacks by Turkish infantry from the south and east, a fierce battle lasted all day, but the Russians were able to repel the enemy onslaught. On August 10 there were no attacks; there was a weapons and artillery exchange of fire. The Turks, without taking the Russian positions on the move, were preparing for a new decisive attack, and the Russians were strengthening themselves. Radetzky, having received news of the enemy offensive, moved a reserve to Shipka - the 4th Infantry Brigade, he led it. In addition, another brigade stationed at Selvi was sent to Shipka (it arrived on the 12th). At dawn on August 11, a critical moment came, the Turks again went on the attack. By this time, our troops had already suffered great damage, and by noon their ammunition began to run out. The attacks of the Turks followed one after another, by 10 o'clock the Russian positions were covered from three sides, at 2 o'clock the Circassians even went to the rear, but were driven back. At 5 p.m., Turkish troops attacking from the western side captured the so-called Side Hill, and there was a threat of a breakthrough in the central part of the position. The situation was already almost hopeless when at 7 o'clock the 16th Infantry Battalion appeared, which Radetzky mounted on Cossack horses, 2-3 people per horse. The appearance of fresh forces and Radetzky inspired the defenders, and they were able to push back the Turks. The side hill was broken off. Then the rest of the 4th Infantry Brigade arrived and the enemy onslaught was repulsed in all directions. Russian troops were able to hold Shipka. But the Turkish troops still had superiority and their combat positions were located only a few hundred steps from the Russians.

Defense of the “Eagle’s Nest” by the Oryol and Bryants on August 12, 1877 (Popov A.N., 1893).

On the night of August 12, reinforcements led by Major General Mikhail Dragomirov (2nd Brigade of the 14th Infantry Division) arrived at the pass. Ammunition, provisions and water were delivered. Radetzky had up to 14.2 thousand men with 39 guns under his command, and he decided to launch a counteroffensive the very next day. He planned to shoot down Turkish forces from two heights of the western ridge - the so-called Forest Mound and Bald Mountain, from where the enemy had the most convenient approaches to the Russian position and even threatened its rear. However, at dawn, Turkish troops again went on the offensive, striking the center of Russian positions, and at lunchtime Mount St. Nicholas. Turkish attacks were repelled in all directions, but the Russian counterattack on the Lesnaya Kurgan was not successful. On August 13 (25), the Russians resumed attacks on Lesnaya Kurgan and Lysaya Gora, by this time Radetsky received more reinforcements - the Volyn regiment with a battery. By this time, Suleiman Pasha had significantly strengthened his left flank, so the stubborn battle for these positions lasted all day. Russian troops were able to knock the enemy off the Forest Mound, but were unable to capture Bald Mountain. Russian troops retreated to the Forest Kurgan and here during the night and morning of the 14th they repulsed enemy attacks. All Turkish attacks were repelled, but Stoletov’s detachment suffered such significant losses that, without receiving reinforcements, they were forced to leave the Forest Mound, retreating to the Side Hill.

Vanguard of the 4th Infantry Brigade, Major General A.I. Tsvetsinsky hurries to Shipka.

In six days of fighting on Shipka, the Russians lost up to 3,350 people (including 500 Bulgarians), i.e., virtually the entire original garrison, including generals Dragomirov (he was seriously wounded in the leg), Derozhinsky (killed), 108 officers. Turkish losses were higher - about 8 thousand people (according to other sources - 12 thousand). As a result, Russian troops were able to win a strategic victory - the breakthrough of Turkish troops through the pass and their decisive offensive against one of the flanks of the extended position of the Russian army would not only force the rest to retreat, but could also lead to cutting them off from the Danube. The position of Radetzky’s detachment, which was furthest from the Danube, was especially dangerous. The question of the withdrawal of Radetzky’s forces and the cleansing of the Shipka Pass was even raised, but then it was decided to strengthen the garrison of the pass. Tactically, the position of our troops at the pass was still difficult, they were surrounded by the enemy from three sides, and the fall and winter worsened even more.

National park-museum at Shipka Pass. "Steel" battery.

"Shipka seat"

From August 15 (27), the Shipkinsky Pass was defended by the 14th Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Brigade, under the command of Major General Mikhail Petrushevsky. The Oryol and Bryansk regiments, as having suffered the greatest losses, were withdrawn to reserve, and the Bulgarian militias were transferred to the village of Zeleno Drevo to take the path through the Imitli Pass, bypassing Shipka from the west. The defenders of the Shipka Pass, doomed to passive defense, from that moment on were most concerned about strengthening their positions and their arrangement. They built closed passages for communication with the rear.

The Turks also carried out fortification work, strengthening their battle formations, and carried out constant weapons and cannon fire on Russian positions. From time to time they made fruitless attacks on the village of Green Tree and Mount St. Nicholas. On September 5 (17), at 3 a.m., Turkish troops launched a strong attack from the southern and western sides. Initially they were successful; they were able to capture the so-called. Eagle's Nest is a rocky and steep cape jutting out in front of Mount St. Nicholas. However, then the Russians counterattacked and, after a desperate hand-to-hand fight, drove the enemy back. An enemy attack from the west, from the Forest Mound, was also repelled. After this there were no serious attacks. The fighting was limited to skirmishes. On November 9, Wessel Pasha attacked Mount St. Nicholas, but very unsuccessfully, because the attack was repulsed with heavy losses for the Turkish troops.

Snow trenches (Russian positions at Shipka Pass). V.V. Vereshchagin.

Soon the Russian soldiers had to endure a serious test, which was carried out by nature. The position of the troops on Shipka became extremely difficult with the onset of winter; frosts and snowstorms on the mountain tops were especially sensitive. In mid-November, severe frosts and frequent snowstorms began; the number of people sick and frostbitten on some days reached 400 people; the sentries were simply blown away by the wind. Thus, three regiments of the arriving 24th division were literally decimated by disease and frostbite. During the period from September 5 to December 24, 1877, combat losses in the Shipka detachment amounted to about 700 people killed and wounded, and up to 9.5 thousand sick.

Battle of Sheinovo December 26 - 28, 1877 (January 7 - 9, 1878)

The last act of the battle for Shipka was an attack on the positions of Turkish troops on the road from Mount St. Nicholas to the village of Shipka (battle of Sheinovo). After the fall of Plevna on November 28 (December 10), the number of Radetzky's troops was increased to 45 thousand people. However, even under these conditions, an attack on the heavily fortified positions of Wessel Pasha (he had about 30 thousand people) was risky.

It was decided to attack the extensive Turkish camp in the valley opposite the Shipka Pass in two columns, which were supposed to make a roundabout maneuver: 19 thousand. eastern column under the command of Svyatopolk-Mirsky, through the Trevnensky pass and 16 thousand. western column under the command of Mikhail Skobelev, through the Imitli Pass. About 10-11 thousand people remained under the command of Radetzky; they remained in the Shipka positions. The columns of Skobelev and Svyatopolk-Mirsky set out on December 24, both columns encountered great difficulties, overcoming snow debris, almost all artillery had to be abandoned. On December 26, Svyatopolk-Mirsky’s column descended to the southern side of the mountains, the main forces took up positions near the village of Gyusovo. Skobelev's column, in addition to natural obstacles, encountered Turkish detachments occupying the heights dominating the southern descent, which had to be occupied by battle. Skobelev's vanguard was only able to reach the village of Imitlia in the evening of December 26, and the main forces were still at the pass.

On the morning of December 27, Svyatopolk-Mirsky launched an attack on the eastern front of the Turkish camp. The camp was about 7 miles in circumference and consisted of 14 redoubts, which had trenches in front and between them. By 1 o'clock in the afternoon, Russian troops captured the first line of Turkish fortifications in this direction. Part of the forces of Svyatopolk-Mirsky occupied Kazanlak, blocking the retreat path of the Turkish troops to Adrianople. The troops of the western column on the 27th continued to knock down the Turks from the dominant heights, and due to the insignificance of the forces that crossed the mountains, Skobelev did not dare to launch an offensive. On the morning of the 28th, the Turks launched a counteroffensive against the eastern column, but were repulsed; the Russians captured Shipka and several fortifications. A further attack on Svyatopolk-Mirsky’s column was impossible, since the attack from Skobelev’s side had not yet begun, and the troops suffered heavy losses and used up most of the ammunition.

Radetzky, having received a report from Svyatopolk-Mirsky, decided to strike at the front of the Turkish positions and draw part of the Turkish forces towards himself. At 12 noon, 7 battalions descended from Mount St. Nicholas, but further advance along a narrow and icy road, under strong enemy rifle and artillery fire, led to such high losses that the Russian troops, having reached the first line of enemy trenches, were forced to retreat. However, this attack diverted significant forces of the Turkish army and artillery, which they could not use for a counterattack against the troops of Svyatopolk-Mirsky and Skobelev.

The battle of Shipka-Sheinovo on December 28, 1877 (Kivshenko A.D., 1894).

Radetsky did not know that at 11 o'clock Skobelev began his attack, directing the main attack on the southwestern part of the enemy positions. Soon his forces burst into the middle of the fortified camp. At the same time, the column of Svyatopolk-Mirsky resumed its offensive. At about 3 o'clock, Wessel Pasha, convinced of the impossibility of further resistance and retreat, decided to capitulate. The troops that held positions in the mountains were also ordered to surrender. Only part of the Turkish cavalry was able to escape.

As a result of the battle of Sheinovo, Russian troops lost about 5.7 thousand people. Wessel Pasha's army ceased to exist, only about 23 thousand people were captured, and 93 guns were also captured. This victory had important consequences - in fact, the shortest route to Adrianople and Constantinople was opened. Thus ended the battle for Shipka.

The defense of Shipka is still one of the symbols of the perseverance and courage of Russian soldiers. For Bulgaria, the name Shipka is a shrine, because this was one of the main battles that brought freedom to the Bulgarian people after almost five centuries of the Ottoman yoke.

“Big” Russian monument on Shipka.

Events on the Balkan Ridge

The assault on Plevna and the defense of Shipka, in fact, took place simultaneously. Looking a little into the future, it can be noted that in both theaters of combat, events developed according to a completely unplanned scenario. Time played into the hands of the Ottoman Empire exclusively.

However, let's return to the present, and while Plevna continued to repel the attacks of the Schilder-Schuldner army, General Romeiko-Gurko in early July, having managed to knock out the Turks from several positions, approached the Shipka Pass. The Russian-Turkish war, in connection with the events near Plevna, began to drag on, but the fighting on Stara Planina indirectly depended on the success of the assault on the city.

It all started with the attack of General Svyatopolk-Mirsky on the northern part of the hill. From the south, Romeiko-Gurko’s detachments advanced towards it. Both Russian offensives were repulsed by the defending Ottomans, but the commander of the Turkish combat units, Hulussi Pasha, considered that remaining on Shipka was too risky and retreated to the city of Kalofer.

The next day, Svyatopolk-Mirsky occupied the hill without a fight, and from the south the pass began to be guarded by the advance detachment of General Fyodor Radetsky. The position itself was very important from a strategic point of view, but it was very difficult to go on the offensive and defend from it. The passages along the ridge themselves were very narrow, which made Shipka difficult to access, but at the same time it could well be subject to crossfire from neighboring heights. There were also no natural shelters.

The plan of the Turkish command was simple: to capture the peak and advance to the northern part of Bulgaria. The total number of the Turkish army before the siege of Shipka numbered almost 30,000 people and more than 30 guns. The number of Russian defenders at the pass was about 6,000 soldiers, including Bulgarian volunteers, as well as two and a half dozen military guns. Thus, before the outbreak of hostilities, both sides were reinforced with reinforcements.

On August 21, 1877, the defense of Shipka acquired the status of a real military clash. Russian troops did not move from their position for more than a month and did not even organize an offensive attempt, since the important transport hub was still in the hands of the Turks.

“Everything is calm on Shipka”

The Balkan Range cuts Bulgaria into two parts - Northern and Trans-Balkan. Communication between them is maintained through several passes, of which Shipkinsky is considered the most convenient. Nowadays, the winding E-85 highway passes through this pass at an altitude of more than a thousand meters above sea level, above which rises a huge monument resembling a chess rook. It was here that one of the most striking and tragic actions of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878 unfolded - the bloody battles for Shipka.

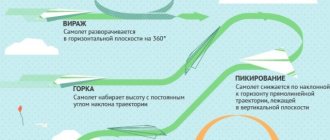

At the beginning of the war, the Russian command planned to cross the Danube and move the fighting to Trans-Balkan Bulgaria as quickly as possible in order to threaten Adrianople and Constantinople. The Shipka Pass was given special attention in these plans - the victorious Russian army had to pass through it to strike at the heart of the Ottoman Empire. The crossing of the Danube on June 15, 1877 was surprisingly easy. It became clear that the Turks did not have time to prepare for defense, and it was necessary to “strike while the iron is hot.”

Monument to Freedom at Shipka Pass. The valley of the Tundzha River is visible in the background Source – bolgarians.ru

General Gurko's raid

The passes in the Balkans represented the second natural barrier on the path of the Russian troops, and an advance detachment under the command of Adjutant General I.V. Gurko rushed towards them in the hope of capturing them before the Turks had time to come to their senses. The detachment, consisting of 30 squadrons and hundreds and 10 ½ infantry battalions with artillery support, captured Tarnovo, the ancient Bulgarian capital and the key to the passes on the northern side, almost without a fight on June 25.

Enemy troops were on Shipka, but the neighboring Khainkoi Pass was not occupied. Gurko walked along it to Trans-Balkan Bulgaria and descended into the valley of the Tundzha River, which lies directly behind the ridge. Seeing the Russian troops, the peaceful Bulgarians could not believe their luck - no one expected that the Russians would invade so deeply into the territory of the Ottoman Empire. In Constantinople, the mood was close to panic. Gurko's detachment interrupted telegraph communications and railway traffic and, finding itself in the rear of the Turkish detachment, forced it to leave the Shipka Pass. Gurko's detachment acted quickly and boldly, supplying itself from the local population and provisions captured from the enemy. The Russian cavalry dismounted for fire combat; the 4th Infantry “Iron” Brigade of Major General A.I. Tsvetsinsky demonstrated excellent training. Thanks to their efforts, the gates to the heart of the Ottoman Empire were in the hands of Russian troops.

Map of the Balkan Theater of Operations Source – pretich2005.narod.ru

However, this was the end of the happy and easy stage of the war for the Russian command. On July 8 and 18, Russian troops unsuccessfully stormed the fortifications of Plevna twice. Since Plevna was located only two crossings from Sistov, where the bridges over the Danube were located, there could be no question of crossing the Balkans without eliminating this threat. An ominous omen of future bloodshed was the sight that greeted Gurko’s soldiers when they climbed the Shipka Pass abandoned by the Turks - in front of the Turkish commander’s tent stood a pyramid of the heads of Russian soldiers. The Turks adhered to ancient eastern military traditions and cut off the heads of the corpses of their enemies.

At this time, the army of Suleiman Pasha was transferred by sea from Montenegro, which soon appeared in front of Gurko’s small detachment. Since the forces were clearly unequal, the Russians had to hastily retreat back to the northern slope. Retreating, everyone in the detachment understood that the Bulgarian population, who joyfully greeted the Russians, was being left to their fate. Revenge on the part of the Turks was not long in coming - according to Bulgarian information, they killed 20,000 civilians in Eski Zagra.

Defense of Stoletov

Now the Russians needed to hold onto the passes at all costs until Plevna was finished. This task fell to the veteran of the Caucasian War, Lieutenant General F. F. Radetsky. This modest man by nature, whom some contemporaries compared to the blessed one, was destined to become one of the main heroes of the Shipka epic. Under his command there were about 50,000 soldiers, with whom it was necessary to cover a front of 120 km. The enemy's intentions remained unclear, so much depended on Radetzky's reserve - the 14th Infantry Division under the command of Adjutant General M.I. Dragomirov, stationed in Tarnovo and ready to advance to the threatened direction.

Lieutenant General F. F. Radetsky, 1878. Artists – P. F. Borel, K. Kryzhanovsky Source – rsl.ru

On August 7, the troops of Suleiman Pasha appeared in front of the Russian positions on Shipka. The Turkish commander lined up all his 60 camps (a Turkish camp roughly corresponded to a battalion, 60 camps - about 30,000 people) in a long line, as if wanting to intimidate the small detachment of Major General N. G. Stoletov, consisting of the 36th Oryol Infantry Regiment and five squads of the Bulgarian militia. If the exhausted 35th Bryansk Regiment had not arrived at the pass on the same day, then the defenders of Shipka could have been considered doomed.

The Russians still had a chance of success thanks to the position occupied by the Oryol, Bryansk and Bulgarians. The road along the pass went past Mount St. Nicholas, which was difficult to access from the front. The mountain was easily shot from the surrounding heights, but climbing it was very difficult. On August 9, the Turks tried to do this for the first time, surrounding the mountain in a semi-ring and starting to build batteries on the neighboring peaks. Then dense columns of Turks rushed to the top. The Russians and Bulgarians fought back desperately, using bayonets and even stones. The actions of the Turkish troops were also complicated by the fact that the approaches to the mountain were mined by Russian sappers. The explosion they caused turned out to be premature and did not inflict losses on the enemy, but for a long time discouraged him from attacking in this direction. The chief of sappers, Lieutenant General V.D. Krenke, was one of the first to report to Radetsky about the situation on Shipka:

“As an eyewitness, I tell you that the situation in the Shipka Pass is desperate; Although the attacks were repulsed, the Turks were increasingly deployed on the surrounding heights, artillery was raised there on oxen, and rifle fire was so strong that there was not a single corner in the entire defended position where one could hide from the shots. The Bryansk regiment, which was not in action, lost 22 people wounded. The big shortage now is in artillerymen. Shipka can be saved by quick help - one that would allow the Turks to attack in order to get out of a passive position.”

A. N. Popov. Defense of the "Eagle's Nest" by the Oryol and Bryants on August 12, 1877. 1893 Source – art-catalog.ru

The position of the Shipka defenders was critical and was aggravated by the lack of supplies - agents of the Horwitz, Greger, Kogan and Co. partnership, which supplied food to the army, fled from the pass at the first rumors of the approach of the Turks. On August 9, 10, 11 and 12, the soldiers did not receive hot food, being content with crackers. Dressing supplies quickly came to an end, and by August 11 it was already necessary to save cartridges. However, the most important shortage for the Russians was water - the heat was forty degrees, and water from mountain springs could only be taken at night with great risk to life.

The Turks set up ambushes not only at the springs, but also along the entire highway leading from Gabrovo, from where they were waiting for rescue reserves. The road was shot through, and one of its sections was called the “paradise valley”, because everyone who stopped there went to their forefathers. On August 9 alone, 40 people were wounded and killed on the road to Gabrov. No one could understand where the fire was coming from, since even gunpowder smoke was not visible. On August 16, the Russians managed to unravel this mystery - they accidentally found a cave from which a group of Turks fired. All of them were bayoneted.

Arrival of Radetzky

The seizure of the initiative by the Turks caused outbreaks of panic among the Russian command - moreover, one such incident almost destroyed the Shipka detachment. At the beginning of August, Major General I.E. Boreysha, who was covering the descent from the Eleninsky Pass near Shipka, reported that his detachment had been pushed back by large Turkish forces. This was exactly what Radetzky feared - Suleiman Pasha began to bypass Shipka along the neighboring passes. A reserve urgently moved to the threatened area, but it soon became clear that Boreisha mistook a small detachment of bashi-bazouks for “large forces.”

Boreisha's mistake is partly due to two reasons. Firstly, after the failures at Plevna, the command fell into despondency and expected attacks from the Turks from all sides. In such an atmosphere, someone must have “imagined” large Turkish forces. Secondly, almost everyone was sure that the Turks would strike at Tarnov either from Lovchi (from the west) or from Osman Bazar (from the east), and Suleiman Pasha would support this attack with a detour along one of the passes. It is still not clear why the Turkish military leaders did not do anything similar. Either the incompetence of the enemy, or the rivalry between the Turkish generals played into the hands of the Russians, and Suleiman Pasha continued to fight against the rocks of Shipka without support.

However, the Russian command had to pay dearly for fantasies about an enemy offensive. Parrying the imaginary threat, Radetsky's reserve made the transition from Tyrnov to Elena (40 versts) on August 8, back on August 9 (another 40 versts), on August 10 - from Tyrnov to Gabrov (42 versts) and on August 11 - from Gabrov to Shipka, where his help was just needed. In forty-degree heat, the soldiers walked about 140 miles in four days, lost a lot of time and several people died from sunstroke, but still managed to help out the Shipkinites. The regiments of the 14th division fraternized with the Oryol and Bryansk people even before the war, and then during the crossing of the Danube, so no one wanted to stay with the convoys, rest in Gabrovo was reduced to a minimum, and the vanguard of the detachment traveled the last miles on horseback behind the Cossacks. Reinforcements arrived at the most critical moment - on the evening of August 11, when Stoletov’s people had been fighting for three days in almost complete encirclement without water or hot food. Along with reinforcements, the long-awaited water was also brought to the defenders of Shipka.

Arrival of the vanguard at Shipka. The author of the painting is unknown Source – encyclopedia.mil.ru

On the morning of August 12, the main part of the 14th division began to arrive at Shipka along with General Dragomirov. Together with a group of officers, Dragomirov climbed to the top of one of the mountains to inspect the position from it, and almost immediately a Turkish bullet pierced the general’s knee. Wounded by the same bullet, Captain Maltsev, the first Russian to set foot on the Turkish bank of the Danube, died the next day. A few hours later, General V.F. Derozhinsky, who was drinking tea, was killed by the same stray bullet, who became the first Russian general to die in the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878. One can imagine how dangerous it was simply to be in the rear of the Shipka position in those August days.

Fortunately for the defenders of Shipka, the Turks were exhausted - their losses reached 6,000 people. The Russians and Bulgarians lost 3,640 people killed, wounded and missing in the August battles, that is, almost a quarter of all forces at the pass. One could assume that the worst was over, but in the last days of August terrible news came to Shipka - the third assault on Plevna ended in vain. This meant that the Shipka epic would not end soon.

Shipka seat

Autumn has arrived in the Balkan Mountains, and with it comes rain and cold. The fighting died down, and the parties began strengthening defensive structures. History has brought to us the story of Shipka, non-commissioned officer of the 54th Minsk Regiment Fyodor Minyaila. What was etched in his memory was not so much the battles as the hard work - the soldiers dug and carried out soil, shoveled snow, carried firewood and water, and built fortifications. The non-commissioned officer’s memories resemble folk epics:

“There was the Babylonian captivity for us; there we sat and sighed for our fatherland; there we cried, sang and remembered our dear homeland..."

The Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878 turned out to be not such an easy walk as it seemed at the beginning, and those who came to Shipka in the fall-winter of 1877 had the hardest time. At the beginning of September, both sides pulled up mortars to Shipka to conduct overhead fire. The artillerymen had to learn to fire from closed positions without seeing their target. On September 5, the Turks launched a daring attack on the Eagle's Nest, which was led by a specially trained assault group using hand grenades. In a word, the situation on Shipka was quite similar to the realities of the First World War.

Map of Russian positions on Shipka Source – Materials for the history of Shipka. St. Petersburg, 1880

Some of the Russian officers remembered the defense of Sevastopol well, so comparisons begged, and they were not in Shipka’s favor. In 1854–1855, the defenders of Sevastopol had dugouts completely protected from fire, but on Shipka there was not a single place where one could feel safe. People lived in huts that provided no protection from rain or Turkish fire. If during the defense of Sevastopol the combat units were replaced (one day the unit occupied positions, the second day it stood in reserve, the third day it was in the city), then the Shipkinites did not have any shifts, since the positions had to be defended with all available forces. Monotonous days and gloomy weather intensified the melancholy, and Turkish shelling shook the nerves of the Shipka defenders. An excerpt from the diary of the commander of the Podolsk regiment, Colonel M. L. Dukhonin, is typical:

“Each of us has already been so shelled that the impression of grenades and the whistling of bullets is tolerated in the trenches quite calmly and many have reached the point of complete disregard for danger... […] But in the same open trenches the effect of overhead fire and bomb explosions is felt completely differently - their flight is visible , and wait for a decision. This agonizing wait is not easy, followed by suffocation, a deafening crash that causes ringing in the ears and shock of the nerves. The fragments hiss as they fly apart, and this deadly roar is not easy to bear. Cast iron and lead rain, relatively speaking, hits or touches only a few, but spoils everyone’s nerves. Of course, over time we’ll get used to bombs, but for now they’re really annoying.”

Commanders began ordering warm clothes for the soldiers, but already on September 26, the first cases of frostbite appeared. In October, the Minsk Regiment reached the peak incidence rate for the entire campaign - 515 cases, that is, almost every sixth person in the regiment was sick. Finally, in November, real frosts arrived in the mountains. By that time, the exhausted Oryol regiment had been replaced by units of the 24th Infantry Division of Adjutant General K.I. Gershelman, but on December 19 this division had to be lowered from Shipka, since it was almost all frozen. Although frostbite was rarely fatal, it did cause severe injury. Herschelman's non-combat losses amounted to more than 50% of the division's full strength. By the second half of December, the frost in the mountains had reached such intensity that the hoods were breaking off in pieces, and the oil was congealing in the rifles.

V.V. Vereshchagin. Picket in the Balkans Source – veresh.ru

Crossing the Balkans

On November 28, Plevna fell, and, according to all the canons of military affairs, the 1877 campaign should have ended there. The decision to cross the snow-capped Balkan Mountains in winter came as a surprise even to many military leaders of the Russian army. Major General M.D. Skobelev was one of the few who demonstrated confidence in success. In the Shipka area, the transition was to take place in three columns along neighboring passes, the left of which was led by Skobelev himself, the central by F.F. Radetsky, and the right by Prince N.I. Svyatopolk-Mirsky. Having descended from the passes, the columns were supposed to simultaneously hit the Turks from three sides. The calculation of the Russian command consisted, first of all, in the surprise of the attack. The one-time attack was scheduled for December 27, and its target was the fortified Sheinovo camp, where the Turks spent the winter, unaware of the Russian intentions.

The main problem of the Shipko-Sheinovsky operation was the almost complete lack of communication between the columns moving along parallel passes. The distances that the columns had to overcome were not the same, and the difficulties of the transition could hardly be predicted. In Skobelev’s column, the Ural Cossacks trampled the path with their horses leading, followed by sappers who shoveled snow, and only then did the bulk of the troops move. In some places, snow walls on the sides of the path completely hid people, and only Cossack peaks were visible from the side. Although the path of the Skobelev column was much shorter than that of Svyatopolk-Mirsky, it did not manage to descend from the pass by the appointed time.

December 27, 1877 arrived - a day that cast a shadow on the reputation of the “White General”. In accordance with the plan, Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky launched an attack on the Turkish camp, counting on the help of the remaining columns. A bloody battle began, in which both sides actively wielded bayonets. Mirsky lost 1,800 people and in the evening reported to Radetzky: “I attacked, no one helped. There is no food, no ammunition, we have to retreat. Help out"

. Skobelev’s units at that time were just descending from the pass and concentrating next to Sheynov. At first, the “White General” reported that he would support the attack in any case, but then changed his mind. Skobelev's orderly, cornet P.A. Dukmasov, a desperate daredevil, in no way lagging behind his boss, made a 16-hour horse march, overcoming the Imetli and then Shipkinsky passes to convey this news to Radetzky.

So, the Russians had to wait for the next day, which began with the Turkish attack on the battered column of Svyatopolk-Mirsky. Radetzky only had to turn his head to the left to see the difficult position of the prince’s troops from the heights of Shipka, and turn his head to the right to see that Skobelev was still not attacking. After waiting until noon, Radetzky moved the Shipkinites, intended for demonstrative actions, from the mountains, and only after that Skobelev finally launched an attack with unfurled banners and music. About a third of Skobelev's musicians fell in this attack - a rare example of such high losses in regimental orchestras. By 15:00 it was all over. The Turks laid down their arms, and the path to Constantinople was clear.

V.V. Vereshchagin. Skobelev in the battle of Shipka-Sheinovo, 1879 Source – gkaf.narod.ru

Why didn’t Skobelev attack for so long? Various assumptions were made on this score, including his personal accounts with Svyatopolk-Mirsky. Most likely, Skobelev really only had negligible forces at hand, since his column was just descending from the mountains. Faced with a difficult choice - sticking to the letter of the plan, launching a risky attack, or waiting and acting for sure - Skobelev decided to play it safe. The units under the command of Svyatopolk-Mirsky and Radetsky bore the brunt of the battle near Sheynov, but the blow of the “White General” turned out to be fatal for the Turks. It was he who captivated the Turkish command and turned out to be the hero of the day. After the war, Radetzky directly told Skobelev: “You have come to a head-to-head analysis to reap laurels.”

.

This whole unpleasant situation could have been avoided if communication between the columns had been established - it is not surprising that many participants in the battle complained about the lack of a telegraph. If during the Avliyar-Aladzhin operation on the Caucasian front, thanks to the telegraph, it was possible to achieve a perfectly synchronized attack on Turkish positions from the front and rear, then in the Balkans this means was neglected. In addition, the weather allowed the Russians to use heliographs, but they were collecting dust somewhere in warehouses beyond the Danube.

The Shipka epic has a sad epilogue. In the August battles, the Russians and Bulgarians lost 3,640 people, the losses in the final Shipko-Sheinovsky battle amounted to about 5,000 people, and between these battles the losses amounted to about 10,000 people. Despite everything, the war brought the Russian army to the walls of Constantinople. In honor of the victory in the war, they ordered a parade, but the appearance of the regiments participating in the Shipka battles was so deplorable that they had to be pulled back, behind the backs of other soldiers. There was a saying among Shipka’s heroes: “Back to the parade, but what’s going on – ahead”

.

List of sources:

- Vereshchagin V.V.

Memoirs of an artist. Crossing the Balkans. Skobelev. 1877–1878 // Russian antiquity. 1889. No. 3. - Gazenkampf M. A.

My diary. 1877–1878 St. Petersburg, 1908. - Dragomirova S. A.

Radetsky, Skobelev, Dragomirov // Historical Bulletin. 1915. No. 2. - Dukhonina E.V.

Peaceful activities in war. M. 1894. - Zolotarev V. A.

Confrontation of empires: the war of 1877–1878. The apotheosis of the Eastern crisis. M., 2005. - Krenke V.D.

Shipka in 1877. Excerpt from the memoirs of Lieutenant General. V. D. Krenke // Historical Bulletin. 1883. No. 1. - Materials for the history of Shipka. St. Petersburg 1880.

- Milyutin D. A.

Diary. 1876–1878. M., 2009. - Naglovsky D.S.

Actions of the advance detachment of General Gurko in 1877 // Military collection. 1900. No. 7. - The story of soldier Fyodor Minyailo about the war of 1877–1878. // Russian antiquity. 1883. No. 12.

- Collection of materials on the Russian-Turkish War of 1877–1878…. Vol. 10.

- Sobolev L.N.

The last battle for Shipka // Russian antiquity. 1889. No. 5. - Greene FV

Sketches of Army Life in Russia. NY. 1880.

Second and third assault on Plevna

Schilder-Schuldner's troops received reinforcements. A new commander, General Nikolai Pavlovich Kridener, arrived with him. Preparations for the second attack on the city were in full swing. At the end of July, the detachments of Skobelev and Baklanov conducted reconnaissance, however, as before, they were unable to obtain any specific information about the defending Ottomans.

The number of the enemy already amounted to more than 20,000 people, including mercenaries - Bashi-Bazouks and Circassians. Since a siege was only a matter of time, the Turks were busy creating fortifications, even despite an acute shortage of materials and tools.

At the end of July, the second siege of Plevna began. By order of General Kridener, the artillery opened fire first. Having destroyed several unfinished positions with enemy guns, the infantry moved forward. Advancing on two flanks and in both directions, the Russians experienced enormous problems. Another lack of coordination of actions, as well as unfamiliar terrain, led to the fact that the Turks, not only were able to repel the Russian army, but also launched a counterattack themselves. This especially affected the left flank, where General Skobelev’s troops fought.

At the end of the day, Kridener ordered a retreat. There were very large human losses on the Russian side, incommensurable with the Turkish ones. On top of that, about a thousand soldiers were captured by the Turks. The Russian Empire was forced to ask Romania for reinforcements.

All that was achieved in August was to capture the city of Lovech, which connected the approaches to Plevna and did not allow the Turks to receive support and provisions. The operation was commanded by General Skobelev.

In September, this time the Turks organized an offensive. Osman Pasha with his army attacked the Russian outposts and was even able to capture one of the redoubts for a while, but was soon driven back to Plevna.

In mid-September, Skobelev's detachment, together with Romanian support under the command of General Angelescu, after an unsuccessful artillery shelling of Plevna, advanced to another assault. The number of attackers was over 80,000 people and more than 400 guns. There were almost two times fewer Turks - about 35,000, and six times fewer guns, a little more than 70.

Even after capturing the trench lines and the Grivitsky redoubt, Skobelev and the Russian-Romanian army were forced to retreat. Plevna, which was not captured, continued to hold back the Russian pressure. Meanwhile, the latter could not advance further and did not in any way influence the events taking place in the meantime within the framework of the Battle of Shipka. As before, the attack again did not bring results.

Continuation of defense on the Balkan ridge

On August 21, 1877, enemy artillery attacked Russian positions from the east. There towered Mount Maly Bedek, from where the infantry began the assault on Shipka a little later. Having successfully repelled the attack, which lasted until night, the defenders began hastily strengthening their positions. The next day, the Ottomans did not force events, but on August 23 they again organized an offensive.

At dawn, the operation to capture Shipka was carried out in three directions. Acting more fiercely, individual units of the Turkish army were able to enter the rear during the day, and by the evening they almost broke through the central line of the defenders. Only the reserve rifle battalions, led by General Adam Cwiecinski, arrived in time and were able to tip the scales in favor of the Russians. However, the defense of Shipka did not end there; the Turkish troops managed to remain in their positions.

At night, several more detachments of Russian infantry arrived, and the next day General Radetzky decided to organize an attack on the western positions of the Turks, Forest Mound and Bald Mountain. This decision was explained by the fact that the enemy was within walking distance from the rear, where two days earlier there had been fierce resistance, which ended successfully only because reserve units had arrived. The troops of Suleiman Pasha also did not sit idly by and resumed attacks on the positions of the defenders. The enemy was repulsed, but Radetzky failed to take the Forest Mound.

New attacks on the two hills began the next day. Having managed to more seriously fortify Bald Mountain, Suleiman Pasha’s troops repulsed the Russians, but at the same time surrendered the Forest Kurgan. The latter, however, was under Radetzky’s control for only a few hours: the Ottoman pressure on the lost position did not stop, and, having suffered very serious losses, the general retreated, losing the mound back to the Turks.

Shipka's defense gradually began to take on a passive character. At the end of August, new units of the Russian reserve arrived at the pass, replacing the soldiers who took part in the battles.

Defense of Shipka

LOCKED DOORS

Shipka are locked doors: in August they withstood a heavy blow with which Suleiman Pasha wanted to break through them in order to enter the vastness of Northern Bulgaria, unite with Mehmed Pasha and Osman Pasha and thereby tear the Russian army into two parts, after which inflict a decisive defeat on her.

And over the next four months, Shipka pinned down the 40,000-strong Turkish army, diverting it from other points in the theater of operations, thereby facilitating the successes of our other two fronts. Finally, the same Shipka prepared the surrender of another enemy army, and in January part of our army passed through its open doors in its victorious march to Constantinople. General F.F. Radetzky

THE WAY TO THE PASS

The defense of Shipka is one of the key and most famous episodes during the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

After crossing the Danube and capturing the bridgehead, the Russian army could begin to carry out its further task - developing an offensive across the Balkans in the direction of Constantinople. From the troops concentrated on the bridgehead, three detachments were formed: Advanced, Eastern (Ruschuksky) and Western. Advance detachment (10.5 thousand people, 32 guns) under the command of Lieutenant General I.V. Gurko, which included squads of the Bulgarian militia, was supposed to advance to Tarnovo, capture the Shipka Pass, transferring part of the troops beyond the Balkan Range, that is, to the southern regions of Bulgaria.

The detachment went on the offensive on June 25 (July 7), 1877 and, having overcome enemy resistance, on the same day liberated the ancient capital of Bulgaria - Tarnovo. From here he moved through the hard-to-reach but unguarded Khainkoi Pass (30 km east of Shipka) to the rear of the enemy located on Shipka. Having crossed the pass and defeated the Turks near the villages of Uflany and the city of Kazanlak, on July 5 (17) Gurko approached the Shipka Pass from the south, occupied by a Turkish detachment (about 5 thousand people) under the command of Hulyussi Pasha.

The Russian command intended to capture the Shipka Pass with a simultaneous attack from the south by Gurko’s detachment and from the north by the newly formed Gabrovsky detachment of Major General V.F. Derozhinsky. On July 5-6 (17-18), fierce battles broke out in the Shipka area. The enemy, considering it impossible to further hold the pass, abandoned his positions on the night of July 7 (19), retreating along mountain paths to Philippopolis (Plovdiv). On the same day, the Shipka Pass was occupied by Russian troops. The advance detachment completed its task. The path beyond the Balkan ridge was open. Gurko’s detachment was faced with the task of blocking the enemy’s path and preventing him from reaching the mountain passes. It was decided to advance to Nova Zagora and Stara Zagora, take up defensive positions at this line, covering the approaches to the Shipka and Khainkoi passes. Fulfilling the assigned task, the troops of the Advance Detachment liberated Stara Zagora on July 11 (23), and Nova Zagora on July 18 (30).

Gurko's detachment, located beyond the Balkans, heroically repelled the onslaught of the advancing 37,000-strong army of Suleiman Pasha. The first battle took place on July 19 (31) near Eski Zagra (Stara Zagora). Bulgarian militias selflessly fought shoulder to shoulder with Russian soldiers. Russian soldiers and Bulgarian militias led by Major General N.G. The Stoletovs inflicted heavy losses on the enemy. But the forces were unequal. Gurko's detachment was forced to retreat to the passes and join the troops of Lieutenant General F.F. Radetzky, who defended the southern sector of the front. After Gurko’s retreat from Transbalkania, Shipka entered the area of the southern front of the Russian army, entrusted to the protection of the troops of General Radetzky (8th Corps, part of the 2nd, 4th Infantry Brigade and the Bulgarian militia), the defense of Shipka was entrusted to the newly created Southern Detachment under the command of Major General N.G. Stoletov, a third of whom were Bulgarian militias.

Considering the important strategic importance of Shipka, the Turkish command set the task of Suleiman Pasha’s army to seize the pass, and then, developing an offensive to the north, connect with the main forces of the Turkish troops advancing on Rushchuk (Ruse), Shumla, Silistria, defeat the Russian troops and push them back for the Danube.

RETURNED 19 ATTACKS

I just had a meeting with a correspondent for the English Daily News, Forbes. He arrived at Shipka on August 12 and was there from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m. He came to us on a horse, which he drove to death. He hurried to Bucharest to be the first to report about the failure of the Turks and how we repulsed 19 of their fierce attacks... He is delighted with our soldiers, and also praises the Bulgarians. He said that he saw how about a thousand residents of Gabrovo, among whom there were many children, carried water to our soldiers and even riflemen to the front line under a hail of bullets. With amazing dedication they carried the wounded from the battlefield.

N.P. Ignatiev

HEROES OF SHIPKA

The position occupied by Russian troops on Shipka was up to 2 km along the front with a depth of 60 m to 1 km, but did not meet the tactical requirements: its only advantage was its inaccessibility. In addition, along its entire length it was subject to crossfire from neighboring dominant heights, providing neither natural cover nor convenience for going on the offensive. The fortifications of the position included trenches in 2 tiers and 5 battery positions; rubble and wolf pits were built in the most important directions, and landmines were placed. By the beginning of August, the equipment of the fortifications was not completed. However, due to strategic requirements, it was necessary to hold this pass at all costs.

Suleiman Pasha sent 12 thousand people with 6 guns to Shipka, who concentrated at the pass on August 8 (20). Stoletov's Russian-Bulgarian detachment consisted of the Oryol infantry regiment and 5 Bulgarian squads (up to 4 thousand people in total, including 2 thousand Bulgarian militias) with 27 guns, to which, already during the battle of the next day, he arrived from the city. Selvi Bryansk regiment, which increased the number of Shipka defenders to 6 thousand people.

On the morning of August 9 (21), Turkish artillery, having occupied the mountain east of Shipka, opened fire. The subsequent attacks of enemy infantry, first from the south, then from the east, were repelled by the Russians. The battle lasted all day; At night, Russian troops, expecting a repeat attack, had to strengthen their positions. On August 10 (22), the Turks did not resume attacks, and the matter was limited to artillery and rifle fire. Meanwhile, Radetzky, having received news of the danger threatening Shipka, moved a general reserve there; but he was able to arrive, and even then with intensive marches, only on August 11 (23); In addition, another infantry brigade with a battery stationed at Selvi was ordered to go to Shipka, which could only arrive in time on the 12th (24th).

The battle on August 11 (23), which became the most critical for the defenders of the pass, began at dawn; by 10 o'clock in the morning the Russian position was covered by the enemy from three sides. The Turkish attacks, repulsed by fire, were renewed with fierce persistence. At 2 o'clock in the afternoon the Circassians even came to the rear of our position, but were driven back. At 5 p.m., Turkish troops advancing from the western side captured the so-called Side Hill and threatened to break through the central part of the position.

The position of the Shipka defenders was already almost hopeless when, finally, at 7 o’clock in the evening, part of the reserve arrived at the position - the 16th Rifle Battalion, raised to the pass on Cossack horses. He was immediately moved to Side Hill and, with the assistance of other units that went on the offensive, recaptured it from the enemy. The remaining battalions of the 4th Infantry Brigade, which then arrived in time, made it possible to stop the Turkish pressure on other parts of the position. The battle ended at dusk. Russian troops held out on Shipka. However, the Turks also managed to maintain their position - their battle lines were only a few hundred steps from the Russians.

On the night of August 12 (24), reinforcements arrived at Shipka, led by Major General M.I. Dragomirov. The size of the Russian-Bulgarian detachment increased to 14.2 thousand people with 39 guns. Shells and cartridges, water and food were brought up. The next day, the Russian-Bulgarian detachment went on the offensive to knock down the Turks from two heights of the western ridge - the so-called Forest Mound and Bald Mountain, from where they had the most convenient approaches to our position and even threatened its rear.

At dawn on August 12 (24), the Turks attacked the central sections of the Russian positions, and at 2 o’clock in the afternoon they attacked Mount St. Nicholas. They were repulsed at all points, but the attack launched by the Russians on Lesnoy Kurgan was also unsuccessful.

On August 13 (25), Radetzky decided to resume the attack on Lesnoy Kurgan and Lesnaya Gora, having the opportunity to bring more troops into action due to the arrival of another Volyn regiment with a battery on Shipka. At the same time, Suleiman Pasha significantly strengthened his left flank. Throughout the day there was a battle for possession of the mentioned heights; The Turks were driven off the Forest Mound, but their fortifications on Bald Mountain could not be captured. The attacking troops retreated to the Forest Mound and here, during the evening, night, and at dawn on August 14 (26), they were repeatedly attacked by the enemy. All attacks were repelled, but the Russian troops suffered such heavy losses that Stoletov, lacking fresh reinforcements, ordered them to retreat to Bokovaya Gorka. The forest mound was again occupied by the Turks.

In the six-day battle on Shipka, Russian losses amounted to 3,350 people (including 500 Bulgarians), 2 generals were disabled (Dragomirov was wounded, Derozhinsky was killed) and 108 officers; the Turks lost 8.2 thousand (according to other sources - 12 thousand). This battle did not have any significant results; both sides remained in their positions, but our troops, surrounded by the enemy on three sides, were still in a very difficult situation, which soon worsened significantly with the onset of autumn bad weather, and with the onset of autumn and winter - cold weather and blizzards.

From August 15 (27), Shipka was occupied by the 14th Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Brigade, under the command of Major General M.F. Petrushevsky. The Oryol and Bryansk regiments, as the most affected, were put into reserve, and the Bulgarian squads were transferred to the village of Zeleno Drevo to occupy the path through the Imitli Pass, which bypasses Shipka from the west.

IF A TURKISH FIELDS FALLS INTO A POT OF PORridge

For the sixth day now our nerves have been strained to the limit. The battle on Shipka does not stop. From yesterday's telegram we learned that another 400 lower ranks and 30 officers were out of action there. Dragomirov's wound is very serious - the knee joint is crushed. General Derozhinsky was killed... But just recently I saw him in Svishtov, fresh, rosy, it seemed like he could live for decades more!

Corps commander Radetzky himself led the column into hand-to-hand combat... My nerves are on edge, because every three to four hours we receive such news. You involuntarily ask yourself the same question: will we really have to retreat under the pressure of these numerous Turkish hordes rushing to the pass? The soldiers do not lose heart, they eat their bitter porridge, and the wounded, leaving the position, even joke as if nothing had happened. If by chance a Turkish field ends up in a pot of porridge, they say that the Turks sent them salt. Some argue that we will endure and will certainly win. Let's hope!

Outstanding Russian doctor S. Botkin

SHIPKA SEAT

“The Shpkin Seat” is one of the most difficult episodes of the war. The defenders of Shipka, doomed to passive defense, were concerned mainly with strengthening their positions and creating, if possible, closed passages of communication with the rear. The Turks also strengthened and expanded their fortification work and continuously showered the Russian position with bullets and artillery shells. On September 5 (17), at 3 a.m., they again launched an attack from the southern and western sides. They managed to take possession of the so-called Eagle's Nest - a rocky and steep cape protruding in front of Mount St. Nicholas, from where they were driven out only after a desperate hand-to-hand fight. The column advancing from the west (from the Forest Mound) was repelled by fire. After this, the Turks no longer launched serious attacks, but limited themselves to shelling the position.

With the onset of winter, the position of the troops on Shipka became extremely difficult: frosts and snowstorms on the mountain tops were especially sensitive. These hardships were especially noticeable for the newly arrived Russian troops: three regiments of the 24th division literally melted away from disease in a short time.

During the period from September 5 (17) to December 24 (January 5, 1878), only about 700 people were killed and wounded in the Shipka detachment, and up to 9.5 thousand were sick. The end of 1877 was also marked by the end of the “Shipka seats,” the last act of which was an attack on Turkish positions on the road from Mount St. Nicholas to the village of Shipka.

The defense of Shipka pinned down significant Turkish forces and provided the Russian troops with the shortest route of attack to Istanbul.

AGAIN ON SHIPKA

When units of the 3rd Ukrainian Front passed through the Shipka Pass in September 1944, Marshal F.I. Tolbukhin wrote the following lines: “It is pleasant for the Russian heart to see monuments to their ancestors outside the Soviet Union.” The built regiments at the Russian military cemetery under the peak of Stoletov fired a rifle salvo in honor of the heroes of Shipka - their fathers and grandfathers, who died far from their homeland for the freedom of the fraternal Bulgarian people. In just one night, Major L.L. Gorilovsky composed poems for a marble plaque, which was installed on the monument to Russian military glory, erected in the place where the “Steel” battery once stood. On it, under the engraved tank, you can read the following poems dedicated to the heroes of Shipka:

Far from the Russian mother earth, Here you fell for the honor of your dear fatherland. You took an oath of allegiance to Russia and remained faithful to the grave.

You were not restrained by the formidable ramparts, Without fear you went into battle, holy and right, Sleep peacefully, Russian eagles, Descendants honor and multiply your glory.

Genov Tsonko. Russian-Turkish War 1877-1878 and the feat of the liberators (chapter 3)

SANCTUARY

Shipka is one of the most famous names in the history of Bulgaria, a shrine of Bulgarian patriots. In commemoration of the defense of Shipka near the pass in 1928 - 1930. a monument was erected.

The largest and most solemn events are held here on March 3 - this is the day of the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano, which brought freedom to Bulgaria after five centuries of Ottoman rule.

And every August, a historical reconstruction of the events of 1877 is held here. An important part of the event is a memorial service for the Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Romanian and Finnish soldiers who died here, as well as for the Bulgarian militias. They are given military honors, government leaders and residents of Bulgaria lay wreaths of fresh flowers at the monument on the top of the hill as a sign of their gratitude.

The material “Defense of Shipka” was prepared by the Research Institute (military history) of the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation

From the “Shipka Sitting” to the capture of Plevna

The soldiers who remained at the pass began to experience difficulties not only from the Ottomans, who regularly shelled Russian positions, but also from the weather. Autumn has begun, gradually turning into winter. In mid-September, Turkish troops took the peak near Mount St. Nicholas, Cape Eagle's Nest, but soon after a predominantly hand-to-hand fight they were driven out of there.

Until the end of the year there were no more serious battles between the opponents, but the weather interfered with the defense of the Shipka Pass. Snow fell regularly at altitude, accompanied by strong winds. During the three months of “sitting”, almost 10,000 infantrymen were out of action due to illness.

Meanwhile, the city of Plevna was under siege. The Turkish defenders of the city managed to replenish themselves with additional reinforcements and provisions in advance. Osman Pasha's garrison increased to almost 50,000 men. The army of the Russian Empire also received reinforcements in the form of the army of General Ganetsky.

The next arenas of hostilities were the villages of Telish and Horni Dybnik. The capture of positions and redoubts in these places ensured a complete blockade of the besieged city. At the beginning of November, a new fierce battle began, during which, at the cost of almost 5,000 Russian soldiers, the key area was taken by Ganetsky’s army.

For some time, local clashes took place in the surrounding area, some attacking others, and vice versa, but no one could have a significant impact on the current state of affairs. Pleven, meanwhile, being completely cut off from the world, received no more provisions or help. The city's garrison began to suffer from hunger and disease, but the commander of the Turkish army, Marshal Osman Pasha, refused to capitulate. Despite the difficult conditions, the Ottomans were in a fighting mood.

In mid-December, the enemy decided to break through by cunning. According to their plan, the army was supposed to break through towards the city of Sofia. Having installed homemade effigies at the fortification sites, the Turks, accompanied by local residents, headed along the planned course. The surprise attack on the advanced Russian regiments initially bore fruit, but the Russian grenadiers reacted with lightning speed to such manifestations of enemy activity and inflicted enormous damage on the latter, putting them to flight. The wounded Osman Pasha capitulated, more than 40,000 Turkish soldiers surrendered, and Plevna, as a result, was taken. Emperor Alexander II, as a sign of the courage and valor of the Turkish marshal, handed him his own saber, which was given to General Ganetsky during the surrender.

The final stage of the operation on the Balkan ridge

General Radetzky, who continued the defense of the Shipka Pass, had almost 45,000 soldiers at his disposal by mid-December, but did not immediately decide to attack the Turks. Wessel Pasha's army seriously strengthened its positions and was ready for Russian attacks.

In the second half of December, it was decided to attack in two columns. The directions of the Trevnensky and Imitli passes were taken as a basis. The regiments were commanded by generals Svyatopolk-Mirsky and Skobelev. A little more than 10,000 soldiers under the leadership of Fyodor Radetsky remained on Shipka. The defense finally smoothly turned to the offensive, but due to difficult weather conditions the columns advanced with difficulty, in addition meeting Turkish resistance along the way.

At the end of December, the forces of Svyatopolk-Mirsky took Kazanlak, closing the Turks’ retreat to Adrianople. Things got worse for Skobelev; he was able to occupy the village of Imitlia with an incomplete detachment, but after that he no longer made active attacks.