In February 1980, Mujahideen attacks on mechanized columns and garrisons of Soviet troops became more frequent; at the end of the month, mass anti-government protests took place in Kabul, and the Soviet embassy was fired upon. After this, the leadership of the USSR decided to begin active military operations jointly with the DRA army to defeat the armed opposition.

According to estimates by the USSR Ministry of Defense, in different years the number of militants opposing Soviet and Afghan government forces in Afghanistan varied from 47 thousand to 173 thousand people.

Since March 1980, Soviet troops carried out military operations in the country, a unified plan for which was approved by the USSR Ministry of Defense. At the same time, with the help of Soviet military specialists, the Afghan armed forces were reorganized and strengthened. Later, in April 1985, OKSV moved from active large-scale combat operations to supporting the operations of Afghan government forces with aviation, artillery and, if necessary, engineer units. Soviet special forces units continued to fight opposition caravans.

In total, in 1979-1989, 416 large-scale operations were carried out to defeat particularly dangerous Mujahideen groups and their large bases. These include the so-called Panjer operations against the militants of the field commander Ahmad Shah Massoud in the Panjer Gorge (1980-1985), the Kunar operation in areas on the border with Pakistan (1985), the operation to defeat the Jawar base area (1986), and Operation Highway in unblocking of the city of Khost (1987-1988) and others.

Soviet troops also almost continuously participated in unscheduled military operations against detected groups of Islamic militants. In 1984-1987, the “Veil” action plan was in effect on the Pakistan-Afghan and Iran-Afghan borders, within the framework of which OKSV military personnel daily set up up to 30-40 ambushes against Mujahideen caravans. In the spring of 1987, the “Barrier” system was introduced - the eastern and southeastern parts of the DRA were blocked by a chain of ambushes and units that guarded road junctions and controlled mountain gorges from the heights. However, after the return of Soviet and Afghan government forces to their deployment points, the Mujahideen often regained control over the territory they had previously lost. The armed Islamic opposition did not have enough strength to overthrow the PDPA regime, and at the same time, government troops, even with the assistance of the OKSV, could not completely eliminate the Mujahideen detachments supported by the United States and Arab countries. In general, the war showed that Soviet troops could not effectively fight against an enemy relying on guerrilla tactics.

Geneva Agreements

After the start of the perestroika process in the USSR and the policy of renouncing the use of force in international relations proclaimed in April 1985, the Soviet leadership began to take measures to reduce the combat strength of the OKSV. In February 1986, at the XXVII Congress of the CPSU, General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev announced the development, together with the Afghan side, of a plan for the phased withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. Soon after this, Babrak Karmal was removed from the post of head of Afghanistan, and the former head of the Ministry of Security, Mohammad Najibullah, became his successor. Under his leadership, a new constitution was adopted, in which there were no guidelines for the construction of communism and socialism, and Islam was proclaimed the state religion.

On September 20, 1986, the first six OKSV regiments were withdrawn from the DRA. In 1987, the Afghan government led by Mohammad Najibullah formulated a new policy of “national reconciliation,” inviting the opposition to stop fighting and sit down at the negotiating table. But the Mujahideen leadership refused negotiations, declaring war to a victorious end. The Soviet troops remaining in the country continued to support the DRA government.

On April 14, 1988, in Geneva (Switzerland), agreements on the Afghan settlement were signed between the foreign ministers of Pakistan and Afghanistan, through the mediation of the UN and the participation of the United States and the USSR as guarantors. The USSR pledged to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan within nine months, and the USA and Pakistan had to stop supporting the Mujahideen. By the time the agreements were signed, the number of USSR troops in Afghanistan reached 100.3 thousand people.

Where it all started

The history of the Afghan war is tragic. In 1978, the April Revolution took place in Afghanistan, as a result of which the People's Democratic Party came to power. The government declared the country a democratic republic. M. N. Taraki took over the post of head of state and prime minister. X. Amin was appointed first deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs.

On July 19, the Afghan authorities suggested that the USSR introduce two Soviet divisions in case of emergency. Our government has made small concessions to resolve this issue. It proposed sending one special battalion and helicopters with Soviet crews to Kabul in the coming days.

On October 10, Afghan authorities officially announced Taraki's sudden death from a serious incurable disease. It later turned out that the head of state was strangled by officers of the presidential guard. There was persecution of Taraki's supporters. The civil war in Afghanistan actually already began in November 1979.

Conclusion OKSV

The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan took place in two stages. From May 15 to August 15, 1988, more than 50 thousand soldiers and officers of the 40th Army left Jalalabad, Ghazni and Gardez in the east, Kandahar and Lashkar Gah in the west, Faizabad and Kunduz in the northeast of the country. From December 1988 to February 15, 1989, the second half of the military units of the 40th Army was withdrawn. On February 4, the last unit of the 40th Army left Kabul, and by February 8, the outposts on the Kabul-Salang Pass road were removed. Two days later, this route was transferred to the protection of Afghan government troops. In the western direction, Soviet units left Shindand on February 4 and Herat on February 12. From February 11 to February 14, all units located in the area from the Salang Pass to Hairoton were withdrawn to the territory of the Turkestan Military District. The withdrawal of the 40th Army was completed on February 15, 1989; the last to leave Afghanistan were Army Commander Lieutenant General Boris Gromov and the border cover detachments.

In October 1991, the Soviet leadership decided to stop military assistance to the Afghan government as of January 1, 1992. In April 1992, Najibullah's regime fell (he himself was killed), power passed to the Mujahideen Transitional Council, which proclaimed the Islamic State of Afghanistan. In November 1994, the radical Islamic movement “Taliban” (banned in the Russian Federation) entered the armed struggle for power in the country; later the Taliban occupied Kabul and proclaimed the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

The main reasons for the failures of the Russian army

At the beginning of the war, luck was on the side of the Soviet troops, proof of this is the operation in Panjshir. The main misfortune for our units was the moment when the Mujahideen were delivered Stinger missiles, which easily hit the target from a considerable distance. The Soviet military did not have equipment capable of hitting these missiles in flight. As a result of the use of the Stinger, the Mujahideen shot down several of our military and transport aircraft. The situation changed only when the Russian army managed to get its hands on several missiles.

Statistical data

In total, according to the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, in the period from December 25, 1979 to February 15, 1989, 620 thousand Soviet military personnel served in Afghanistan. Of these, 525.2 thousand (including 62.9 thousand officers) served in the 40th Army, 90 thousand - in the border and other units of the KGB of the USSR, 5 thousand represented the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) ) THE USSR. In addition, about 21 thousand people were in civilian personnel positions in the troops.

According to a statistical study edited by Colonel General Grigory Krivosheev, “Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century,” the total irretrievable human losses of the Soviet side in the Afghan conflict amounted to 15 thousand 51 people. Control bodies, formations and units of the Soviet Army lost 14 thousand 427 people, KGB units - 576 people, formations of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs - 28 people. Other ministries and departments (Goskino, Gosteleradio, Ministry of Construction, etc.) lost 20 people. During the same period, 417 military personnel went missing or were captured in Afghanistan, of which at least 130 were released during the conflict and in subsequent years.

Over 200 thousand OKSV military personnel, as well as workers and civil servants, were awarded orders and medals. 86 Soviet military personnel were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union for their courage and heroism (25 posthumously). According to official data, 147 tanks, 118 aircraft, 333 helicopters, 1,314 armored vehicles and 433 artillery systems were lost in the battles.

During the withdrawal, Soviet troops handed over free of charge to the Afghan side about 2 thousand 300 objects for various purposes, including 179 military camps (32 garrisons), left 990 armored vehicles, about 3 thousand cars, 142 artillery pieces, 43 rocket artillery installations, 82 mortars, 231 units of anti-aircraft weapons, 14.4 thousand units of small arms, 1 thousand 706 grenade launchers.

The decision to send troops into Afghanistan

They wanted to replace the deceased head of state Taraki with a more progressive figure. Therefore, after his death, Babrak Karmal took over the post.

On December 12, after coordinating his actions with the commission of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee, Brezhnev decided to provide military assistance to Afghanistan. On December 25, 1979, at 15.00 Moscow time, the entry of our troops into the republic began. It should be noted that the role of the USSR in the Afghan War was enormous, since Soviet units provided all possible support to the Afghan army.

Organization and tactics of Afghan partisans

History shows that Afghans are freedom-loving and fanatically devoted to their religious and cultural traditions. They are convinced that every Mujahideen (“fighter for the faith”) who fell in the fight against the atheist communists is destined for a place in heaven. In addition, any Afghan considers participation in war to be the best way to confirm his courage and gain popularity (“high rating”) among his fellow tribesmen.

Just like the entire Afghan society, the forces of the Afghan rebels were divided ethnically, geographically, and religiously. Numerous attempts by various resistance groups to unite have failed to eliminate their division into two main factions: Islamic fundamentalists and moderate nationalists. In the first of these groups, three parties played a leading role: Hezb-i-Islami, led by Hekmatyar; the party of the same name under the leadership of Khales; Jamiat-i-Islami under the leadership of Rabbani (the latter was influential mainly among Tajiks and was distinguished by the high professionalism of its field commanders).

There were more supporters of moderate nationalists than Islamic orthodoxies. In their grouping, three parties also had the greatest influence: the National Islamic Front (leader - Gailani); “Harakat-i-Yenqelab-I-Islami” (leader - Mohammadi); "Jabha-Neyat-i-Melli" (leader - Mojadadi).

Both of these groups united Sunni Muslims. But 10-15% of Afghanistan's population are Shia Muslims, living mainly in the central and western provinces. They have their own parties that are trying to follow the ideas of the leader of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini. The Sunni majority of Afghans have a very negative attitude towards the teachings of the Iranian prophet.

Be that as it may, it was the named parties and groups that represented the Afghan resistance forces in Pakistan, China, Iran and the rest of the world. The main channel for the supply of weapons and equipment to the rebels was Pakistan. Most of the training centers were located there. Therefore, the combat capabilities of individual detachments strongly depended on the nature of the relationship between the parties representing them and the authorities of that state.

The real power in the Afghan resistance was the field commanders. Among them, four are the most famous. This is Ahmad Shah Massoud, a Tajik, commander of the joint forces in the Panjshir Valley in the northeast of the country. The north and northwest were dominated by Ismail Khan, an Uzbek and former captain in the royal army. In Kabul itself and in its environs, the “urban guerrillas” of Abdul Haq became famous. In the south and southwest, the combined partisan forces were led by Amin Bardak. In addition to those listed, there were approximately 200-250 more regional commanders operating in Afghanistan, most of them independent of anyone. The total number of Afghan resistance fighters during different periods of the war fluctuated between 120 and 200 thousand people.

The partisans' weapons at first (in 1979-81) consisted mainly of old Russian, English and German rifles, often from the World War of 1914-18, as well as hunting rifles. Later, thanks to supplies from Egypt and China, the defection of government troops to the side of the rebels, the seizure of trophies on the battlefield, purchases from international arms dealers,

partisan detachments received completely modern weapons of Soviet, Chinese, and American design. The most common models were: PPSh-41 submachine guns; Kalashnikov assault rifles AK-47, AKM, AK-74; assault rifles M-14 and M-16; SVD sniper rifle; light machine guns RPD, RPK, PK; RPG-2 and RPG-7 hand grenade launchers; heavy machine guns SG-43 and SGM; heavy machine guns DShK (12.7 mm) and KPV (14.5 mm); hand grenades RG-42, RGD-5, RKG-3; mortars with caliber 57 and 82 mm; 82 mm recoilless rifle; 23 mm automatic anti-aircraft gun; Chinese multiple launch rocket system (caliber 107 mm, range up to 8 kilometers); hand-held anti-aircraft missiles SA-7 (Igla-1) made in Egypt and China, “Stinger” made in the USA. Anti-personnel and anti-tank mines were predominantly of Chinese, Egyptian, Italian, and Pakistani origin.

The Afghan resistance movement was significantly different from similar movements in other countries in that it never had a single command and a single strategic plan for combat operations. At the regional level, there were three main concepts of warfare:

1. In the south and southeast of the country, settled and semi-nomadic tribes, as well as residents of mountain villages, fought. The combat troops here were commanded by local sheikhs, who were fully supported by Muslim priests (mullahs). Military operations were usually carried out after the harvest, i.e. between August and December. Each upcoming operation was discussed by the entire detachment and the plan was accepted only if all fighters without exception agreed. The main type of combat operations were night attacks on strongholds of government or, much less frequently, Soviet troops. After the next raid, the fighters went home until the next time. In battle they behaved very bravely, but in purely military terms they were illiterate, so they suffered heavy losses.

2. The concept of Izmail Khan (north and north-west) was to have in each village a well-armed and trained detachment of 200-300 people, always ready for battle. Essentially, this was the concept of active self-defense, since such units fought only in the vicinity of their villages, without moving too far from them (maximum - at a distance of 15-20 km).

3. Ahmad Shah Masud (northeast) fought on a larger scale and more successfully than anyone else. His concept was based on the experience of the communist wars in China and Vietnam. Masud created three types of units: a) self-defense units in each village, consisting of local residents; b) detachments that operated only within their permanent areas (approximately the same as the detachments of Izmail Khan). They consisted of 30-40 people (usually young people) with light small arms. These people were distinguished by good military and ideological training. Each detachment had an Islamic "political commissar"; c) mobile detachments of experienced fighters operating at a considerable distance from their bases, including those sent to support local self-defense forces. Such detachments had the best weapons, including heavy small arms (recoilless guns, mortars, etc.). The total number of units of the third type at the height of the Afghan war was approximately 4 thousand people.

4, The concept of urban guerrilla warfare (in Kabul, Herat, Kandahar and other relatively large cities of the country). In an interview he gave in Peshawar (Pakistan), Abdul Haq outlined the concept this way: “In the city, the guerrillas use primarily explosives and pistols. Due to constant checks on the streets and searches, it is impossible to use other weapons. The partisans are blowing up fuel depots, concentrations of trucks, barracks, and government offices. In addition, we are destroying power grids, state industrial enterprises, strongholds of Soviet and puppet troops, and committing sabotage at airfields. Often our operations are supported by mortar fire or multiple launch rocket systems located outside the city.”

* * *

Three main types of fighting by Afghan guerrillas can be distinguished :

a) Defense of mountain valleys and villages

Before the Soviet attack on the valley (village), the partisans evacuate the entire population to the mountains. Thus, during one offensive in Panjshir, 35 thousand people were evacuated. At the entrance to the valley (on the approaches to the village), they install minefields, guided land mines, and construct obstacles that impede the movement of armored vehicles. The main road is usually left open to allow attacks from the flanks and rear.

Fire weapons were initially represented only by light small arms. But gradually they were reinforced with mortars, heavy and heavy machine guns, automatic anti-aircraft guns, and multiple rocket launchers. These weapons were located in earthen shelters; from artillery fire and aerial bombardment, the Mujahideen usually hid in rocky caves. Their ammunition depots were also located there.

b) Ambushes against supply columns

The main target of these ambushes was, as a rule, tankers with fuel. The security of such columns usually consisted of two tanks (T-54, 55, 72), two armored personnel carriers and a platoon of motorized rifles. First, the column was stopped in a place convenient for attack by explosions of mines or guided landmines. Then they opened fire from grenade launchers at tanks and armored personnel carriers, and from light machine guns and mortars at tankers and trucks. At this time, snipers destroyed those who tried to organize defense (officers, machine gunners). Large-caliber machine guns protected the Mujahideen from Soviet combat helicopters flying to the rescue of the ambushed convoy. It took at least 20 minutes to receive air support when attacking a convoy. Therefore, in many cases, the Mujahideen managed to launch a fire strike and begin to retreat before helicopters appeared over the battlefield.

c) Blockade of strong points and garrisons

The blockade tactics consisted of wearing out the enemy with mortar and rocket attacks at night, sniper fire during the day, and installing anti-tank mines on roads and anti-personnel mines on trails. The partisans' mortars and rocket launchers did not have permanent positions, but changed them every time. The blockade was successful only against the troops of the Kabul regime. Often they could not stand it and either left their positions to the location of the main forces or surrendered. Soviet troops responded to the night shelling with artillery fire, aerial bombardment of partisan positions, and raids by special forces units.

d) Attacks on cities

Sometimes the partisans concentrated large forces (up to 20-25 thousand people) in the vicinity of Kabul and several other important cities (such as Herat, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Khost) and carried out powerful fire raids. They fired at the locations of Soviet and government troops from mortars, recoilless and automatic guns, multi-barrel rocket launchers, and heavy machine guns. Under the cover of this fire, small groups of partisans tried to penetrate city blocks, destroying enemy soldiers and military equipment along the way, destroying their fortifications and communications. Like the blockade, this type of military action was relatively successful only against Kabul government troops.

* * *

The weaknesses of the partisans were the following: low professionalism of commanders, inability to effectively use modern weapons, poor medical care for the wounded.

Most units lacked junior commanders with tactical training. Therefore, numerous mistakes were made, for example, reckless head-on attacks, accompanied by large losses. And if a Soviet barrier appeared on the path along which food and ammunition were delivered to the detachment, the partisans preferred to engage in battle with it, instead of simply changing the route.

The majority of the partisans, illiterate, had an extremely vague understanding of such things as ballistic trajectory or explosion dynamics. Therefore, they rarely used mortars and rocket launchers correctly. The consumption of shells for them was disproportionately large compared to the results of the fire. They did not know how to independently make mines and grenades, or correctly lay minefields and landmines.

Very few partisans survived after being seriously wounded. And from moderate injuries, the majority became disabled. There are three reasons for this. Firstly, there is a shortage of doctors, medicines, and instruments in the detachments. Secondly, the habit of Afghans to steadfastly endure the most severe wounds and burns, as a result of which they either did not seek help from doctors at all, or did it too late. Thirdly, poor care for the wounded, unsanitary conditions, and non-compliance with the regime prescribed to the wounded.

Origins

Causes of the war in Afghanistan 1979 - 1989 variety. But let's try to look at the main ones. After all, manuals and textbooks often immediately write about the coup in Kabul on April 27, 1978. And then follows a description of the war.

So that's what it really was. After World War II, revolutionary sentiments began to emerge among young people in Afghanistan. There were a lot of reasons: the country was practically feudal, power belonged to the tribal aristocracy. The country's industry was weak and did not satisfy its own needs for oil, kerosene, sugar and other necessary things. The authorities didn’t want to do anything.

Noor Muhammad Taraki

As a result, the youth movement Vish Zalmiyan ("Awakened Youth") arose, which then turned into the PDPA (National Democratic Party of Afghanistan). The PDPA was formed in 1965 and began preparing a coup d'etat.

The party advocated democratic and socialist slogans. I think it’s clear why the USSR immediately relied on it. In 1966, the party split into Khalqists (“Khalq” is their newspaper) led by N.M. Taraki and Parchamists (“Parcha” is their publication) by B. Karmal.

The Khalqists advocated more radical actions, the Parchamists were supporters of a soft and legal transition of power: its transfer from the aristocracy to the workers' party.

In addition to parties, by the beginning of the 70s, revolutionary sentiments also began to grow among the army. The army was separated from the aristocracy, recruited according to the tribal principle and consisted of ordinary Afghans. As a result, in July 1973, she overthrew the monarchy and the country became a republic.

It would seem that everything was fine, because both the Khalqists and the Parchamists were at one with the army. Now real progressive reforms will come to the country! On July 17, 1973, the new President Mohammed Daud read out an “Address to the People,” in which he outlined a number of fundamental progressive reforms.

And if they could be realized, then... But this could not be done. Because immediately after the revolution, a split arose again in the new political circles: M. Daud’s supporters (bourgeoisie, capitalists) wanted to direct the development of the country along the Western path, and the army along the non-capitalist - socialist path, following the example of the countries of the socialist camp.

As a result, from 1973 to 1978 nothing was done. In 1977, the Khalqists and Parchamists united because they realized the futility of their empty argument. On April 27, 1978, the army staged a second revolution and overthrew M. Daoud under the leadership of the PDPA. There was no one else to do this except the army; it was the main driving force in the country!

Hafizullah Amin

At first everything was great: the government headed by N.M. The Tarakis carried out land reform in the interests of the people, forgave all the debts of peasants to local feudal lords, and equalized women's rights with men.

But soon disagreements began again in the party. B. Karmal is already preparing a new coup, and Prime Minister H. Amin used monstrous means: mass killings and imprisonment of ordinary people began. So Amin fought against illiteracy of the population and solved other problems according to the principle: “No person, no problem!”

In October 1979, before L.I. Brezhnev, who met with Taraki a month ago, received the news of his death. The KGB reported that Amin had carried out a new coup d'etat in Afghanistan. The Soviet leadership decided to intervene in the internal political affairs of Afghanistan. This was, as we now know, a monstrously wrong decision.

The Soviet leadership did not take into account the specifics of the region: in fact, the PDPA did not have serious social support from the population - there was a deep gap between the party and the people. And after the revolution, trust in it fell even more due to the actions of Kh. Amin.

But in December 1979, the special forces of the KGB of the USSR carried out another coup. Kh. Amin was killed, and the country was formally headed by B. Karmal. However, the local population perceived the Soviet troops brought into the country as occupiers. In fact, a full-scale civil war began: the PDPA and the USSR against the opposition. The opposition was led by radical Islamists who carried out propaganda among the local population.

Irrevocable losses

On February 15, Russia solemnly celebrated the 25th anniversary of the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. The more pathos and great power there are in these “state events,” the more acutely you understand the tragedy of the people who went through the Afghan melting pot - the dead, the deceased, the survivors, their relatives and friends. The political and military history of the Afghan War as a whole has been written. There will be no new chapters in this big book, only pages. But the human history of this tragedy (and all wars, without exception, are tragedies) is still being written, and every day some growing child in a family that lost an “Afghan” asks: “Why did my grandfather die? How it was? Where did he die?

Brothers of the revolution devouring each other

In almost any country there are people who are ready to make decisions to sacrifice human lives to protect certain state, especially geopolitical, interests.

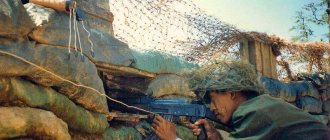

Soviet army soldier in Afghanistan. Photo: Victor Khabarov

The immediate cause of direct Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979 was the obvious political and socio-economic collapse of the April (Saur) Revolution (April 27-28, 1978, 7 Saur 1357 according to Muslim chronology), as a result of which the USSR-backed People's Republic came to power -Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), which proclaimed the country the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA).

The president of the country up to this point (actually a dictator) Mohammed Daoud (who, in turn, seized power in 1973 with the help of a military coup) was killed during the storming of his residence, and members of his family were also killed.

The Revolutionary Council, headed by a chairman, became the new highest state body of Afghanistan; the government was subordinate to the council.

The leaders of the ruling People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan became the chairmen of the Revolutionary Council. The first of them was Noor Mohammad Taraki .

The party pursued a policy of “revolutionary impatience,” including with regard to Islam, and quickly caused massive discontent among wide sections of society, including the growth of armed resistance. In the PDPA, naturally, the brutal Afghan-style factional struggle, which was essentially a struggle of feudal clans, intensified.

On July 1, 1978, the leader of the Parcham PDPA faction, Babrak Karmal, was removed from his post by Nur Mohammad Taraki and sent as ambassador to Czechoslovakia.

In September 1979, the confrontation between Nur Mohammad Taraki and his deputy, Hafizullah Amin , leader of the PDPA Khalq faction, began. By the decision of the plenum of the Central Committee of the PDPA, Taraki was removed, power passed to Amin, on whose orders Taraki was secretly killed on October 2, 1979.

After coming to power, Amin began persecuting all his political opponents (including Karmal’s supporters), many of whom were forced to hide abroad (for example, in the USSR) due to the threat of murder.

Taraki's repression also affected the army, the main support of the PDPA, which led to a drop in its already low morale and caused mass desertion and rebellion.

During this intraspecies struggle, the leadership of “revolutionary Afghanistan” directly called on the USSR to intervene in the conflict on the side of the ruling elite, hoping to stay in power through Soviet help.

The intra-Afghan opposition to the revolutionaries from the PDPA began, in turn, to rely on the help of the United States, which saw Afghanistan as another field of confrontation with the USSR in the struggle for global influence and against the socialist camp.

The Soviet leadership was afraid that a further aggravation of the situation in Afghanistan due to the struggle within the PDPA would lead to the fall of the PDPA regime and the coming to power of forces hostile to the USSR. This fear became the main driver of Soviet policy towards Afghanistan.

“Approve the considerations and measures outlined by Comrade Andropov Yu.V., Ustinov D.F., Gromyko A.A.”

Back in March 1979, during the uprising in Herat, the Soviet leadership received the first request from the Afghan leadership for direct Soviet military intervention (there were about twenty such requests in total).

Soldier of the Government Army in Afghanistan. Photo: Sergey Maximishin

However, the CPSU Central Committee Commission on Afghanistan, created back in 1978, reported to the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee about the evidence of the serious negative consequences of direct Soviet intervention, and the request was rejected.

But the temptation to “respond to geopolitical challenges” and “repel the forces of imperialism” ultimately prevailed.

It was decided to prepare for the overthrow of Hafizullah Amin and his replacement with a leader more loyal to the USSR. Yuri Andropov , was considered as such .

The Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee adopted decision No. P 176/125 on the introduction of a “limited Soviet contingent” into Afghanistan on December 12, 1979: “To position in “A”. Approve the considerations and activities outlined by Comrade Andropov Yu.V., Ustinov D.F., Gromyko A.A. Allow them to make unprincipled adjustments during the implementation of these activities. Issues requiring a decision by the Central Committee should be submitted to the Politburo in a timely manner. The implementation of all these activities is entrusted to comrade. Andropova Yu. V., Ustinova D. F., Gromyko A. A. Instruct t.t. Andropov Yu.V., Ustinova D.F., Gromyko A.A. to inform the Politburo of the Central Committee about the progress of the planned activities.”

In 1979, the only member of the Politburo who did not support the decision to send Soviet troops to Afghanistan was Alexei Kosygin , and from that moment Kosygin had a complete break with Leonid Brezhnev and his entourage.

At the same time, the Chief of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces, Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, was also against the deployment of troops.

When developing the operation to overthrow Hafizullah Amin, it was decided to use his own requests for Soviet military assistance.

At the beginning of December 1979, the so-called “Muslim battalion” was sent to Bagram - a special purpose detachment of the GRU, specially created in the summer of 1979 from Soviet military personnel of Central Asian (Muslim) origin - to guard Taraki and carry out special tasks in Afghanistan (officially - a separate special detachment appointment (ooSpN), in official documents there is also another name - a separate motorized rifle battalion (omsb), indicating the number).

The “Muslim battalion” was unable to prevent the reprisal against Taraki and became Amin’s guard.

The flywheel of military intervention began to spin. In early December 1979, USSR Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov told a narrow circle of officials from among the top military leadership that a decision would obviously be made in the near future on the widespread use of Soviet troops in Afghanistan.

Since December 10, on the personal instructions of Ustinov, the deployment and mobilization of units and formations of the Turkestan and Central Asian military districts near the border with Afghanistan was carried out.

At the “Gathering” signal, the 103rd Vitebsk Guards Airborne Division was raised, which was assigned the role of the main striking force in the upcoming events.

By the evening of December 23, 1979, the minister was informed that the troops were ready to enter Afghanistan.

On December 24, Dmitry Ustinov signed secret directive No. 312/12/001, which stated: “A decision was made to introduce some contingents of Soviet troops stationed in the southern regions of our country into the territory of the DRA in order to provide assistance to the friendly Afghan people, as well as create favorable conditions for prohibiting possible anti-Afghan actions on the part of neighboring states.”

The directive did not provide for the participation of Soviet troops in hostilities on the territory of Afghanistan; even the procedure for using weapons for self-defense was not determined.

True, already on December 27, Ustinov’s order appeared to suppress the resistance of the rebels in cases of attack. It was assumed that Soviet troops would become garrisons and take protection of important industrial and other facilities, thereby freeing up parts of the Afghan army for active action against opposition forces, as well as against possible external interference.

On the evening of December 27, Soviet special forces stormed Amin’s palace, which was also guarded by the Soviet “Muslim battalion.” Operation “Storm” lasted 40 minutes, during the assault Amin was killed. According to the official version published by the Pravda newspaper, “as a result of the rising wave of popular anger, Amin, together with his henchmen, appeared before a fair people’s court and was executed.”

On the night of December 27-28, Babrak Karmal was delivered by air to Kabul, captured by Soviet troops, from Bagram; Kabul radio broadcast his appeal to the Afghan people, in which the “second stage of the revolution” was proclaimed.

The former head of the USSR KGB Directorate, Major General Yuri Drozdov , noted that the leaders of the USSR did not plan to stay in Afghanistan for a long time. According to him, there was a plan for the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan already in 1980, prepared personally by him together with Army General Sergei Akhromeyev . This document was subsequently destroyed on the instructions of the Chairman of the USSR KGB, Vladimir Kryuchkov .

Every year, 800 million US dollars were allocated from the USSR budget to support the regime of Babrak Karmal.

The maintenance of the 40th Army and the conduct of combat operations in Afghanistan annually cost the USSR budget 3 billion US dollars.

In the late 1980s, Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Nikolai Ryzhkov formed a group of economists who, together with specialists from various ministries and departments, were supposed to calculate the cost of this war for the Soviet Union. The results of the work of this commission are unknown. According to the general, former commander of the 40th Army, Boris Gromov , “probably even the incomplete statistics turned out to be so stunning that they did not dare to publish them. Obviously, at present no one is able to name an exact figure that could characterize the expenses of the Soviet Union for the maintenance of the Afghan revolution.”

“There should be no liberties here. Answers should be concise and more standard."

But the heaviest losses were human.

Only on August 17, 1989, the Pravda newspaper published official data on the dead Soviet military personnel, broken down by year: 1979 - 86 people, 1980 - 1484 people, 1981 - 1298 people, 1982 - 1948 people, 1983 - 1448 people, 1984 - 2343 people, 1985 - 1868 people, 1986 - 1333 people, 1987 - 1215 people, 1988 - 759 people, 1989 - 53 people. Total - 13,833 people.

Subsequently, the total figure increased slightly. As of January 1, 1999, irretrievable losses in the Afghan war (killed, died from wounds, diseases and accidents, missing in action) were estimated as follows: Soviet Army - 14,427, KGB - 576 (including 514 border troops), Ministry of Internal Affairs - 28. Total - 15,031 people.

Among them are 11,549 sergeants and soldiers, 632 warrant officers, 2,124 officers, 5 generals, 139 workers and employees.

9,511 people are considered killed in battle.

The so-called “sanitary losses” amounted to almost 54 thousand wounded, shell-shocked, and injured; 416 thousand sick.

But there is also other data. A study conducted by a group of officers of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR under the leadership of Professor Valentin Runov estimates that 26,000 died, including those killed in battle, those who died from wounds and diseases, and those who died as a result of accidents.

A breakdown by year is also given, but the figures are approximately: 1979 - up to 150 people, 1980 - about 2800 people, 1981 - about 2400 people, 1982 - about 3650 people, 1983 - about 2800 people, 1984 - about 4400 people, 1985 - about 3500 people, 1986 - about 2500 people, 1987 - about 2300 people, 1988 - about 1400 people, 1989 - up to 100 people, a total of about 26,000 people.

The reason for this discrepancy in the data is clear: information about those killed in Afghanistan was secret.

Until 1987, zinc coffins with the bodies of the dead were buried in semi-secrecy, and it was forbidden to indicate on monuments that the soldier died in Afghanistan.

Here is the working record of the meeting of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee on July 30, 1981:

“... Suslov . I would like some advice. Comrade Tikhonov presented a note to the CPSU Central Committee regarding perpetuating the memory of soldiers who died in Afghanistan. Moreover, it is proposed to allocate a thousand rubles to each family for the installation of tombstones on their graves. The point, of course, is not about money, but about the fact that if now we perpetuate the memory, we write about it on the tombstones of graves, and in some cemeteries there will be several such graves, then from a political point of view this is not entirely correct.

Andropov. Of course, they need to be buried with honors, but it’s too early to perpetuate their memory.

Kirilenko . It is not practical to install tombstones at this time.

Tikhonov. In general, of course, it is necessary to bury it; whether inscriptions should be made is another matter.

Suslov. We should also think about answers to parents whose children died in Afghanistan. There should be no liberties here. Answers should be concise and more standard.”

According to official statistics, during the fighting in Afghanistan, 417 Soviet soldiers were captured and went missing (of which 130 were released before the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan).

The fate of those captured was different, but an indispensable condition for preserving life was the adoption of Islam.

At one time, the uprising in the Pakistani Badaber camp near Peshewar received wide resonance, where on April 26, 1985, a group of Soviet and Afghan captured soldiers tried to free themselves by force, but died in an unequal battle.

In 1983, in the United States, through the efforts of Russian emigrants, the Committee for the Rescue of Soviet Prisoners in Afghanistan was created. Representatives of the Committee managed to meet with the leaders of the Afghan opposition and convince them to release some Soviet prisoners of war, mainly those who expressed a desire to remain in the West (about 30 people, according to the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Of these, only three people, after the statement by the USSR Prosecutor General that former prisoners would not be subject to criminal prosecution, returned to the Soviet Union.

Even after information about the level of hostilities in Afghanistan became practically common knowledge at the everyday level, a special censorship regime was in effect for the media.

On June 19, 1985, the “List of information permitted for open publication regarding the actions of a limited contingent of Soviet troops on the territory of the DRA” appeared (signed by Valentin Varennikov and Vadim Kirpichenko ). It stated:

"1. Continue publishing previously allowed activity information... and show:

- the presence of units and subunits... without showing their participation in hostilities;

- organization and progress of combat training... on a scale not exceeding a battalion;

- awarding Soviet military personnel without showing their specific combat activities that served as the basis for the award;

- separate isolated facts (no more than one per month) of injuries and deaths of Soviet military personnel in the performance of military duty, repelling an attack by rebels, performing tasks related to providing international assistance to the Afghan people...

2. Additionally, allow publication in the central press, the press of military districts, republican, regional and regional publications:

- about individual cases of heroic actions of Soviet military personnel... showing their courage and fortitude;

- about the daily activities of units, up to the battalion (division) inclusive...

- facts of concern for Soviet military personnel who served in the troops on the territory of the DRA and became disabled, members of the families of those killed in Afghanistan;

- information describing the military exploits, heroism and courage of Soviet soldiers... and the facts of their awards.

3. It is still prohibited in open publications information that reveals the participation of Soviet troops in hostilities on the territory of the DRA - from company level and above, as well as about the experience of their combat operations, the specific tasks of the troops, and direct reports (film, television filming) from the field battle.

4. Publication of any information specified in paragraphs 1 and 2 is permitted in agreement with the Main Military Censorship...

5. Continue the wide publication of counter-propaganda materials by Soviet and foreign authors exposing the falsification of Western media.”

“Everyone is young, everyone thirsts for exploits and glory”

Due to censorship policies at the beginning of the war, soldiers and junior officers heading to Afghanistan had no information about what was actually happening in Afghanistan - about the fighting, about the dead and wounded.

“Few of those leaving for Afghanistan clearly understood the nature of the upcoming service. The desire for exploits, fights, the desire to show oneself as a “real man” - that was it. And it would be very beneficial if someone older were next to the young guys,” recalled battalion commander Mikhail Pashkevich . “Then this youthful impulse and energy would be compensated by calmness and worldly wisdom.” But a soldier is 18-20 years old, a platoon commander is 21-23, a company commander is 23-25, and a battalion commander is good if he is 30-33 years old. Everyone is young, everyone thirsts for exploits and glory. And it so happened that this wonderful human quality sometimes led to losses.”

In total, during the period from December 25, 1979 to February 15, 1989, 620 thousand Soviet military personnel served in the troops on the territory of Afghanistan, of which 525 thousand were in formations and units of the Soviet Army, 90 thousand were in the border and other units of the KGB of the USSR ., in the internal troops of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs - 5 thousand people.

In addition, there were 21 thousand people in the positions of workers and employees in the Soviet troops during this period. The annual listed number of Soviet troops as part of a limited contingent ranged from 80 to 104 thousand military personnel and 5-7 thousand workers and employees (civilians).

There are sources that say about a million people passed through Afghanistan.

USSR soldiers distrusted the Afghan population. The experience of the Soviet special forces showed that if an Afghan detained during an operation was released, he usually returned with a detachment of partisans. Many special forces believed that the entire population of Afghanistan, to one degree or another, helped the Mujahideen.

There was a widespread guerrilla war against Soviet troops in Afghanistan.

There are known examples when, after a battle that ended in the defeat of the special forces, old men and teenagers from the nearest village combed the area and finished off the wounded special forces with hoes and shovels. Local residents gave false information to Soviet soldiers and led them into ambushes.

The majority of Soviet troops in Afghanistan considered the local population enemies, everywhere - mujahideen, regardless of gender and age.

At the same time, Afghan government troops waged what was essentially a civil war with Afghan partisans, the Taliban, who controlled most of the country's territory.

On June 7, 1988, in his speech at a meeting of the UN General Assembly, the President of Afghanistan, Mohammad Najibullah , said that “from the beginning of hostilities in 1978 to the present” (that is, until June 7, 1988), 243.9 thousand government troops were killed in the country , security agencies, government officials and civilians, including 208.2 thousand men, 35.7 thousand women and 20.7 thousand children under 10 years of age; Another 77 thousand people were injured, including 17.1 thousand women and 900 children under the age of 10 years.

The exact number of Afghans killed in the war is unknown. The most common figure is 1 million dead; Available estimates range from 670 thousand civilians to 2 million overall.

According to American researcher of the Afghan war, Professor Mark Kramer , “over the course of nine years of war, more than 2.7 million Afghans (mostly civilians) were killed or maimed, and several million more became refugees, many of whom fled the country.” There appears to be no precise division of victims into government soldiers, mujahideen and civilians.

The result of hostilities from 1978 to 1992 was the flow of Afghan refugees to Iran and Pakistan.

At the same time, the level of military discipline in Soviet units in Afghanistan was often low. Hazing flourished in them, sometimes leading to the death of military personnel. Many soldiers and officers abused readily available alcohol and drugs. According to the testimony of former special forces officer Alexei Chikishev , in some companies and batteries, up to 90% of the rank and file smoked charas (a type of hashish).

Soviet military tribunals sentenced Soviet military personnel to various penalties, including the death penalty, for killing Afghans and raping Afghan women.

Here is the testimony of a military investigator: “The second, Volodya, was surprised all the time: “Comrade captain, are they really going to judge us for these five?” I say: “Guys, you didn’t kill people in battle, you robbed them.” But they don’t understand me, why they are going to be punished. And they tell the following story: “During a raid in Herat on market day, some shooting began in the central market. Whether they shot at us or not, we didn’t understand. The commander commands: “Load fragmentation, fire!” And we fired a fragmentation shell at the crowd from a cannon. We don’t even know how many people died there. And no one said a word. And you here are only five of us!” It didn’t fit in their heads; it seemed to them that there was nothing to judge them for.”

The terrible combat, often monstrously cruel experience of the Afghan War gave rise to difficult fruits after returning home.

The warring parties in all ethnic conflicts on the territory of the former USSR recruited Afghan veterans into the ranks of militants. Many of them joined organized criminal groups.

As of November 1989, about 3,700 veterans of the Afghan war were in prison, the number of divorces and acute family quarrels in the families of “Afghans” was 75%; more than two-thirds of veterans were not satisfied with their jobs and often changed jobs due to emerging conflicts, 90% of Afghan students had academic debt or poor academic performance, 60% suffered from alcoholism and drug addiction.

Back in the late 1980s, there was a widespread sentiment among the “Afghans,” clearly expressed in a letter from one of them to Komsomolskaya Pravda: “You know, if they were now to shout across the Union: “Volunteers!” Back to Afghanistan! - I would have left... Instead of living and seeing all this crap, these snickering faces of office rats, this human anger and wild hatred of everything, these stupid, useless slogans, it’s better to go there! Everything is simpler there."

Testing conducted in the early 1990s showed that at least 35-40% of participants in the war in Afghanistan were in dire need of help from professional psychologists.

And, as a rule, they did not receive it.

“Although the Soviets are traitors, he considers it his duty to send military advisers home safe and sound”

There was essentially no alternative to the decision to gradually limit the use and phased withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan.

The later it was adopted, the higher the cost of war in human lives would be.

On April 7, 1988, a meeting was held in Tashkent between the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev and the President of Afghanistan Mohammad Najibullah, at which decisions were made allowing the signing of the Geneva Agreements and the beginning of the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan.

On April 14, with the mediation of the UN in Switzerland, the foreign ministers of Afghanistan and Pakistan signed the Geneva Agreements on a political settlement of the situation around the situation in the DRA. The USSR and the USA became guarantors of the agreements. The USSR pledged to withdraw its contingent within a 9-month period, starting on May 15; The United States and Pakistan, for their part, had to stop supporting the Mujahideen.

On February 15, 1989, Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan. The withdrawal of the troops of the 40th Army was led by the last commander of the Limited Military Contingent, Lieutenant General Boris Gromov. According to the official version, he was the last to cross the border river Amu Darya (Termez) and declared: “There is not a single Soviet soldier left behind me.”

But this was not true, since Soviet soldiers who were captured by the Mujahideen remained in Afghanistan, as well as border guard units that covered the withdrawal of troops and returned to USSR territory only in the afternoon of February 15.

The border troops of the KGB of the USSR carried out tasks to protect the Soviet-Afghan border in separate units on the territory of Afghanistan until April 1989.

But even after that, Soviet military advisers worked in Afghanistan.

Soviet General Alexander Lyakhovsky wrote in his book “Tragedy and Valor of Afghanistan”: “The last seven of our military advisers left Afghanistan on April 13, 1992. As Major General V.V. Lagoshin , the night before Najibullah invited him to his place and said that the military advisers urgently need to leave Afghanistan, since in the very near future power will pass to the opposition, and he himself has only days left as president five. At the same time, he added that although the Soviets were traitors, he considered it his duty to send the military advisers home safe and sound. Indeed, when the administration of the Kabul airfield began to put forward various obstacles regarding the reception and departure of the Soviet plane, Najibullah personally came to the airfield and assisted in sending advisers to Tashkent.”

The Soviet military mission in Afghanistan did not achieve any of the goals that were set in 1979.

Major General Yevgeny Nikitenko , who was deputy chief of the operations department of the 40th Army headquarters in 1985-1987, believes that throughout the war the USSR pursued constant goals - suppressing the resistance of the armed opposition and strengthening the power of the Afghan government.

Despite all these efforts, the number of opposition forces only grew from year to year, and even in 1986 (at the peak of the Soviet military presence) the Mujahideen controlled more than 70% of the territory of Afghanistan.

In November 1988, three months before the final withdrawal of Soviet troops, according to the KGB, GRU, the headquarters of the 40th Army, the provinces of Bamyan, Paktika and Kunar completely came under the control of the Mujahideen.

Najibullah's government controlled about 8.5 thousand villages (28%) out of 30,191, 22 provincial centers out of 27, the city of Khost, 39 districts and 91 district centers out of 290.

The limited contingent of Soviet troops did not defeat the armed opposition of the Mujahideen.

The civil war in Afghanistan continued.

In 1992, three years after the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, the government of Mohammad Najibullah, who had perhaps the only chance to ensure the development of Afghanistan peacefully, was overthrown by the armed opposition.

On September 27, 1996, the Taliban captured Kabul. They broke into the UN mission building, where Najibullah and his brother had been since his overthrow in 1992, since he could not leave Afghanistan, captured and took both of them away. The brothers were brutally tortured and shot, publicly mocking the bodies of the dead.

+ + +

On August 11, 1988, the organization Al-Qaeda (International Jihad Strike Fund against Jews and Christians) was created to wage jihad around the world.

The main goal set for the organization is the overthrow of secular regimes in Islamic states and the establishment of an Islamic order based on Sharia.

Veterans of the war against Soviet troops in Afghanistan became the striking force of al-Qaeda. In the fight against Soviet military personnel, they attended the highest military field school.

History has completed its tragic turn.

The ring has closed.

Thousands of people paid with their lives for the will of politicians to achieve geopolitical exploits.

The absolute majority of USSR citizens killed and injured in the Afghan War could not escape their fate: they carried out orders.

The courage of most of them is undeniable.

But this personal courage is not a justification for political adventurism, but proof of its inhumanity.

Interesting

Interesting facts about the Afghan war:

- Soviet soldiers nicknamed the war in Afghanistan “The Sheep War” because the Mujahideen drove sheep into them to clear minefields.

- Some experts also consider serious drug trafficking to the Soviet Union from Afghanistan to be one of the reasons for the war.

- Throughout the war, 86 soldiers, including 11 posthumously, were awarded the Order of Hero of the Soviet Union. In total, 200 thousand people were awarded medals of various degrees, including 1,350 women.

- A long time ago, on some livejournal blog, I read an article about a Soviet soldier, a young guy who alone stopped a convoy of Mujahideen and apparently destroyed it, too, alone. If anyone knows this story, write in the comments the name of the hero and a link to his story.

If you know more interesting facts about this war, write in the comments.

When preparing the article, I used the book: N.I. Pikov. War in Afghanistan. M. - Military Publishing House, 1991 Share on social media. networks

The main reasons for the outbreak of hostilities in Afghanistan

The situation in Afghanistan has never been considered calm due to the location of the republic in the geopolitical region. The main rivals wishing to have influence in this country were at one time the Russian Empire and Great Britain. In 1919, the Afghan authorities declared independence from England. Russia, in turn, was one of the first to recognize the new country.

In 1978, Afghanistan received the status of a democratic republic, after which new reforms followed, but not everyone wanted to accept them. This is how the conflict between Islamists and Republicans developed, which ultimately led to civil war. When the leadership of the republic realized that they could not cope on their own, they began to ask for help from their ally, the USSR. After some hesitation, the Soviet Union decided to send its troops to Afghanistan.

"Civil War Rumbles"

After the April revolution of 1978, the Afghan government made attempts to gain the support of the people: schools and hospitals were opened, factories were built, and peasants could receive land for free. However, in a country with strong Islamic traditions, such tactics led to diametrically opposite results: opposition groups were organized in provincial areas, and as a result of the government’s fight against illegal groups, residents of peaceful villages often came under attack.

The year of the beginning of the civil war is considered to be 1978, when the Afghan government declared war on the dushmans - armed rebels. A significant event was the uprising in the city of Herat (March 1979). The likelihood of the city being captured by opposition representatives was quite high, and, fearing for the shaken government, the Afghan leadership began negotiations with the Soviet government and providing military assistance to suppress the rebellion. Realizing the consequences of sending troops into Afghanistan, the leadership of the USSR in early March 1979 chose to stay away from the conflict.

The Afghan government army managed to localize the rebellion, but this did not lead to an improvement in the situation in the country. The civil war flared up more and more: illegal bandit groups were able to take control of the mountainous and rural areas, and also occupied a number of cities. Simultaneously with the decline in the popularity of Nud Mohammed Taraki in the political arena, the rating of Hafizullah Amin, a supporter of the idea of establishing order exclusively by military force, was rapidly growing.

After short political games, supporters of Mohammed Taraki attempted to assassinate Amin. The consequences developed rapidly: Nur Mohammed Taraki was removed from all positions and expelled from the PDPA membership, and in September 1979 he was killed. Having headed the government of Afghanistan, Hafizullah Amin actively began to cleanse the ranks of the Parcham PDPA faction and the clergy, but this did not help solve the problem with the rebels. Moreover, more and more often, soldiers and officers of the active army began to go over to the side of the Mujahideen.

Change of power

In March 1985, power in the USSR changed, the post of president passed to M. S. Gorbachev. His appointment significantly changed the situation in Afghanistan. The question immediately arose of Soviet troops leaving the country in the near future, and some steps were even taken to implement this.

There was also a change of power in Afghanistan: M. Najibullah took the place of B. Karmal. The gradual withdrawal of Soviet units began. But even after this, the struggle between Republicans and Islamists did not stop and continues to this day. However, for the USSR, the history of the Afghan war ended there.

The second, active stage of the war 1980-1985

Border troops of the KGB of the USSR take control of the border areas with Afghanistan. To achieve this, control is being strengthened; combined combat detachments of Soviet and Afghan border guards are being created 10-15 kilometers deep into the DRA. On January 10 and 11, 1980, the artillery regiments of the 20th Afghan Division mutinied.

In March, the first large-scale Kunar offensive against the Mujahideen took place. In April, a military operation is carried out in Panjshir and in the same month the US Congress officially allocates $15 million to the dushmans. In the summer, some of the formations are withdrawn from Afghanistan to the USSR, but the KGB special forces group “Karpaty” arrives. At the same time, in the city of Kishima, a column of a detachment of the 40th Army was ambushed.

In 1981, the main battles take place in September in the province of Farah, and in October the second Muslim battalion arrives. In 1983, a plan for the withdrawal of the 40th Army appeared, but due to the death of Andropov, it was not implemented. The USSR is trying to establish contact with the United Nations. In the summer, the Mujahideen make an unsuccessful attempt to blockade the city of Khost. In winter, the opposition begins to become active in the areas of Sarobi and the Jalalabad Valley. At the same time, the Mujahideen created permanent fortified areas.

The next year of war in Afghanistan brought heavy losses to the 40th Army. In the winter of January 16, 1984, the Mujahideen shot down an SU-25, and in the fall an IL-76. On April 30, during an ambush, the 1st battalion of the 682nd motorized rifle regiment was almost destroyed by the opposition.

In 1985, in order to destroy caravans of Mujahideen from Pakistan, the Soviet garrison of the city of Asadabad was reinforced with the 5th separate motorized rifle battalion. On April 21, this combat detachment advanced to the Marawar gorge on the Afghan-Pakistan border to capture an American instructor. There the battalion is ambushed by the opposition and loses a third of its strength. According to versions, this happened due to the detachment’s lack of training and the self-confidence of its commanders.

Also during this period of the war in Afghanistan, a truce between the Soviet command and the Mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud occurred several times, and even the 40th Army helped him in the fight against the Islamic Party of this country.