A stumbling ditch for tanks

Most of the failures of the Soviet troops in 1941-1942.

in one way or another connected with the sparse formation of formations, when divisions occupied stripes much wider than the statutory norms. The accompanying mistakes in determining the direction of the enemy's attack made the picture of events quite obvious and explainable. The Crimean Front was the complete opposite of all this: its troops occupied a defensive position on a narrow isthmus and had (at least from the point of view of statutory requirements) sufficient means for defense. It seemed almost impossible to miss the direction of the enemy's attack on such a front. Accordingly, most often the defeat of the Crimean Front was associated with the activities of L.Z. Mehlis and D.T. Kozlova. The first was the representative of Headquarters in Crimea, the second was the commander of the Crimean Front.

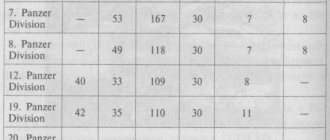

Is it possible to confirm this version 70 years after the war, having documents from both sides? Diving into the details leaves more questions than the outline of the version about the overly active L.Z. provides answers. Mehlis and the “non-Hindenburg”1 comfront D.T. Kozlova. Within the framework of the traditional version, it is completely incomprehensible how the Crimean Front was not defeated a month and a half before the fateful May 1942. For some reason, then, Soviet troops quite successfully repelled the attack of the fresh German 22nd Tank Division, which had just arrived in Crimea from France. Even then, she was given decisive tasks - to cut off the main forces of the Crimean Front with a blow to the shore of the Sea of Azov. The German counterattack ended in complete failure and demands that Hitler personally deal with it.

The circumstances of the events were as follows. The next offensive of the Crimean Front began on March 13, 1942, but no decisive result was achieved. After a week of fighting, the Soviet units were pretty battered and exhausted. On the other side of the front, the situation was also assessed without much optimism. The command of the 11th Army and personally commander E. von Manstein considered the situation of their troops to be extremely difficult. Upon the arrival of the fresh 22nd Tank Division in Crimea, it was on the march, and until the units were completely concentrated, it was thrown into battle in the early morning of March 20, 1942. The counterattack pursued ambitious goals - with a strike through the village of Korpech to the northeast, to cut off the main forces of the Soviet 51st Army Crimean Front.

Despite the initial success, a massive tank attack (about 120 tanks at a time - for the first time in the Crimea) forced the Soviet infantry to abandon their positions, and then events began to develop according to an extremely unpleasant scenario for the Germans. The stream that crossed the division’s offensive line, which the Germans considered surmountable even for a Kübelwagen,2 was scarred and turned by Soviet sappers into an anti-tank ditch. German tanks huddled near the stream came under heavy fire from Soviet artillery. At this moment, Soviet tanks appeared.

It must be said that after a week of difficult and unsuccessful offensive, the tank forces of the 51st Army were not in the best condition. They were represented by the 55th tank brigade of Colonel M.D. Sinenko and a combined tank battalion of combat vehicles from the 39th, 40th tank brigades and the 229th separate tank brigade (8 KV and 6 T-60 on March 19).

By 5.00 on March 20, the 55th brigade had 23 T-26 cannon and 12 flamethrower XT-133 in service. This seemingly tiny amount of armored vehicles finally turned the tide of the battle in favor of the Soviet troops. KVs shot at German tanks, while lighter vehicles dealt with infantry. As noted in the brigade’s report following the battles, “flamethrower tanks were especially effective, destroying enemy infantry running back with their fire”3. The 22nd Panzer Division was put to flight, leaving 34 tanks of all types on the battlefield, some of them serviceable. German casualties amounted to more than 1,100 people.

The main reason for the failure was the unpreparedness of the fresh unit for the conditions of the war in Crimea. Manstein described its features in a report to the Supreme Command of the Ground Forces, hot on the heels of the events: “The high consumption of artillery ammunition, constant attacks by very large aviation forces, the use of multiple rocket launchers and a large number of tanks (among them many of the heaviest) turn battles into a battle of equipment, in no way inferior to the battles of the World War."4 It should be noted here that the formations of the Crimean Front operated under the same harsh conditions. If everything fit into the simple formula “Mehlis and Kozlov are to blame for everything,” the Crimean Front would have been finished at the end of March 1942.

Special month: From May 1941 to May 1945

The most terrible war in the history of not only our country lasted for 1418 days and nights. If we count in months, then 48, in each of which unprecedented feats were accomplished, in each of which the fate of our Motherland was decided, and each of them is therefore memorable for something. For millions of Soviet citizens, any of them could have become and for many, alas, became the last.

May is a special month in this series. Because, of course, it was in the last month of the spring of 1945 that Nazi Germany, which treacherously attacked the USSR, capitulated. But during all the years of the war there were other memorable May days that predetermined our Victory.

May 1941

The chronicle of the Great Patriotic War usually begins in June 1941, with the now notorious words of V.M. Molotov , “at four o’clock in the morning, without declaring war”... But any war, and especially the most terrible one in human history, has a so-called pre-war period. Of course, the Great Patriotic War also had one.

Preparing for the Bustard Hunt

During the preparation of the operation “Hunting for Bustards,” the German command took into account all the lessons of the battles of January-April 1942. Remembering the negative experience with a stream turned into a ditch, detailed information was collected about the anti-tank ditch in the rear of Soviet positions. Aerial photography, interviews with defectors and prisoners made it possible to evaluate this engineering structure and find its weaknesses. In particular, it was concluded that it was completely futile to break through heavily mined (including sea mines) crossings across the ditch. The Germans decided to build a bridge across the ditch after breaking through to it away from the crossings.

The main thing that was done by the German command was the concentration of forces and means sufficient to defeat the troops of D.T. Kozlova. One of the common misconceptions regarding the events of May 1942 in Crimea is the belief in the quantitative superiority of Soviet troops over the German strike force. It is a consequence of an uncritical assessment of the data of E. von Manstein, who wrote in his memoirs about carrying out an offensive “with a ratio of forces of 2:1 in favor of the enemy”5.

Today we have the opportunity to turn to the documents and not speculate with Manstein about the “hordes of the Mongols.” As is known, by the beginning of the decisive battle for the Kerch Peninsula, the Crimean Front (with part of the forces of the Black Sea Fleet and the Azov Flotilla) numbered 249,800 people6.

In turn, the 11th Army on May 2, 1942, based on the number of “eaters”, numbered 232,549 (243,760 on May 11) military personnel in army units and formations, 24 (25) thousand Luftwaffe personnel, 2 thousand people from Kriegsmarine and 94.6 (95) thousand Romanian soldiers and officers7. In total, this gave over 350 thousand people to the total strength of Manstein’s army. In addition, several thousand personnel of the imperial railways, SD, Todt’s organization in Crimea and 9.3 thousand collaborators, designated in the German report as “Tatars,” were subordinate to her.

In any case, there was no talk of the numerical superiority of the Crimean Front over Manstein’s troops aimed at it. Strengthening occurred in all directions. The 11th Army was given the VIII Air Corps, specially trained for interaction with ground forces by the Luftwaffe air force. At the beginning of May 1942, 460 aircraft arrived in Crimea, including a group of the latest Henschel-129 attack aircraft.

Another common misconception is the thesis about the offensive grouping of the front, which supposedly prevented it from effectively defending itself. Documents currently available indicate that the Crimean Front at the turn of April-May 1942, without any doubt, went on the defensive. Moreover, reasonable assumptions were made about the possible directions of enemy attacks: from Koi-Asan to Parpach and further along the railway and along the Feodosia highway to Arma-Eli. The Germans in “Hunting the Bustard” chose the second option and advanced in May 1942 along the Armagh-Eli highway.

Trap

The success of the first days of the offensive played an ominous role in subsequent events. As new units were introduced into the breakthrough, tens of thousands of soldiers climbed deeper and deeper into the trap. Later, an opinion even arose that the Germans deliberately lured the attackers into a prepared bag. Although an analysis of documents from the German command refutes this version.

Soviet soldiers during the offensive in the Kharkov direction, 1942. (waralbum.ru)

On May 17, the German group of Ewald von Kleist launched a strike from the Kramatorsk area on the southern flank of the breakthrough. Marshal Timoshenko became nervous. He was unable to organize a solid defense in the German offensive zone or come up with a bold maneuver. And in fear of the leader’s anger, he did not dare to talk about retreat and began to ask for new reinforcements. The danger of encirclement was fully appreciated by the Chief of the General Staff, Alexander Vasilevsky. But Stalin did not want to hear about the withdrawal of troops from the Barvenkovsky ledge.

On May 18, it became obvious that the pincers around the trap into which a huge Soviet group had fallen were about to close. Vasilevsky persistently proposed to begin the immediate withdrawal of troops. But when asked from Moscow about the situation, Marshal Timoshenko reported that there was no danger of encirclement. His words were confirmed by Nikita Khrushchev, a member of the Military Council of the Southwestern Front. And Stalin forbade retreat.

Ammunition on a starvation ration

The long preparation for the operation allowed the Germans to choose a vulnerable sector of the defense of the Crimean Front. This was the strip of the 44th Army of the Hero of the Soviet Union, Lieutenant General S.I., adjacent to the Black Sea. Chernyak. The 63rd Mountain Rifle Division was located in the direction of the planned main attack of the Germans. The national composition of the division was varied. As of April 28, 1942, out of 5,595 junior command personnel and privates, there were 2,613 Russians, 722 Ukrainians, 423 Armenians, 853 Georgians, 430 Azerbaijanis and 544 people of other nationalities8. The share of the peoples of the Caucasus was quite significant, although not dominant (for comparison: 7,141 Azerbaijanis served in the 396th Infantry Division, with a total strength of the division of 10,447 people). On April 26, units of the 63rd Division participated in a private operation to improve positions; it was not successful and only increased losses. The situation was aggravated by a shortage of weapons. So, on April 25, the division had only four 45mm cannons and four 76mm divisional cannons, and 29 heavy machine guns. The “cherry on the cake” was the absence of a barrier detachment in the division (they appeared in the Red Army even before order N 227 “Not a step back”). The division commander, Colonel Vinogradov, motivated this by the small number of the unit.

Shortly before the German offensive, on April 29, 1942, General Staff officer in the 44th Army, Major A. Zhitnik, in his report to the chief of staff of the Crimean Front, prophetically wrote: “It is necessary either to completely withdraw [the division] ... to the second echelon (and this is the best) or at least in parts. Its direction is the direction of the enemy’s probable attack, and as soon as he accumulates defectors from this division and is convinced of the low morale of this division, he will strengthen his decision to deliver his attack in this sector.”9 Initially, the plan did not provide for a change of division, only a rotation of regiments within the formation with withdrawal to rest in the second echelon10. The final version, approved on May 3, 1942, envisaged the withdrawal of the division to the second echelon of the army on May 10-11, two days later than the start of the German offensive11. Major Zhitnik was heard, but the measures taken were late.

In general, the 63rd Mountain Rifle Division was one of the weakest formations on the Crimean Front. At the same time, it cannot be said that she was a complete outsider in terms of weapons. Poor availability of 45-mm guns was a common problem for Soviet troops in Crimea; their number in divisions ranged from 2 to 18 per division, with an average of 6-8 pieces. Of the 603 “forty-five” guns required by the state, the Crimean Front had only 206 guns of this type as of April 26, of the 416 divisional 76-mm guns - 236, of the 4754 anti-tank guns required by the state - 137,212. The problem of anti-tank defense was somewhat mitigated by the presence of four regiments of 76-mm USV cannons, but they still needed to be in the right place at the right time. A massive enemy tank attack would have become a big problem for any division of the Crimean Front. It is also often forgotten that in 1942 the Red Army was on a starvation diet both in terms of weapons and ammunition. It was difficult to organize the Kursk Bulge of July 1943 in Crimea in May 1942 with the help of four “forty-fives” and 29 “Maxims”.

To a large extent (and this was clearly demonstrated by the episode of March 20, 1942), the anti-tank defense of the troops of the Crimean Front was provided by tanks. By May 8, 1942, the front tank forces had in service 41 KV, 7 T-34, 111 T-26 and flamethrower KhT-133, 78 T-60 and 1 captured Pz.IV13. A total of 238 combat vehicles, mostly light. The core of the Crimean Front's tank forces were KV tanks. According to the plan, two brigades with 9 kV were deployed in the 44th Army zone. In the event of an enemy attack, a counterattack plan was developed using several options, including an enemy strike in the zone of the neighboring 51st Army.