In October 1942, the US command began to intensively prepare for military operations together with Great Britain in North Africa. The purpose of the operation, called "Torch" ("Torch"), was to seize bridgeheads in the territories of states under the control of the French pro-fascist Vichy government (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia), and subsequently, together with the 8th British Army, pushed back to this time to Egypt, defeat German-Italian troops throughout the African continent.

American transport plane flying over the pyramids of Egypt

According to the plans of the allied command, the landing in Casablanca (Morocco) was to be carried out by American troops under the command of Major General J. Patton. American troops under the command of Major General L. Fredendoll also landed in Oran (Algeria). British and American troops arrived from England, under the command of Lieutenant General K. Anderson, were sent to capture the port of Algiers (Algeria). Subsequently, the last two groups of troops were to form the 1st Army under the command of Anderson. To facilitate the capture of airfields in Oran, it was decided to airlift American airborne troops there from England.

Allied forces

For the invasion of North Africa, the Allies allocated 13 divisions and up to 450 combat and transport ships. The overall command of these forces was entrusted to the American General D. Eisenhower. For its part, the Vichy government in North Africa could oppose the Americans with up to 200 thousand people, about 80 warships and up to 500 aircraft. However, French troops did not pose a serious threat to the Allies, as they reluctantly agreed to fight on the side of Germany.

American cemetery and memorial in Tunisia dedicated to American soldiers killed in North Africa

US Army Sherman tank in Tunisia

Fast victory

On November 8, the Allies began simultaneous landings of troops at three planned points. About 107 thousand people landed in the first echelon (35 thousand in Morocco and 72 thousand in Algeria). As the Allied command expected, the French troops offered virtually no resistance. By November 11, allied units had completely occupied the cities of Algiers, Oran and Casablanca. At the same time, French troops stopped resisting. Having captured strategically important bridgeheads, the allied command began to land the second echelon of troops. In total, by December 1, more than 250 thousand people had been landed in North Africa. Between November 8 and November 13, the Allies lost about 2.2 thousand people killed and wounded. French losses reached 500 people killed.

Future 34th President of the United States

From November 1942 to October 1943, D. Eisenhower commanded the Allied forces during the offensive in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. After the so-called “Second Front” was opened, Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander of the Expeditionary Force and led all Anglo-American units during the Channel landing and the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944.

American General Dwight David Eisenhower (1890–1969)

Share link

Tanks in Operation Torch

The landing in North Africa in November 1942 was the first large-scale strategic amphibious operation undertaken by the Western Allies in World War II. At the same time, it became the first combat operation in which American tanks took part en masse. Before armored vehicles were sent into battle, they had to be transported to Africa by sea and then unloaded ashore, possibly under enemy fire.

Throw across the ocean

The Allied command did not expect to encounter serious resistance in Morocco and Algeria. The Vichy regime's forces in the region were estimated at 8 divisions (actually about 60,000 men), and were reportedly not prepared to fight the Americans. Moreover, some of the French commanders (for example, the head of the Algerian garrison, Brigadier General Charles Mast) entered into secret negotiations with the Americans in advance, intending to surrender their positions without a fight. Therefore, it was assumed that the more forces were landed the first time, the less stubborn the French would resist.

The Allied command was much more concerned about the German-Italian troops in Libya—the Tank Army “Africa” of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. The operation planning committee created by the Americans understood that immediately after the landing the Germans would make every effort to transfer their forces from Italy to Tunisia through the narrowest point of the Mediterranean Sea. True, this would first have to be done by air, so the Americans believed that within a week after the landing, the Germans would be able to gather and transfer only 8,000–10,000 soldiers to Tunisia, and without vehicles and heavy artillery.

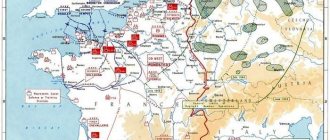

Advance of Allied forces from Egypt to Tunisia, November 1942 - February 1943. historicalresources.org

In order to prevent the further transfer of German troops by sea, it was necessary to capture the ports of Tunisia as quickly as possible, and to do this, land as close to them as possible. According to the calculations of the Americans, to occupy Tunisia an army corps was required, reinforced by one tank division, and in total for Operation Torch - ten infantry and two tank divisions.

Tank landing craft

The main problem of the operation was the landing craft for tanks. Both the British and American navies had a sufficient number of infantry landing craft LCA (Landing Craft Personnel or Landing Craft Assault), which were transported on the davits of transports and launched already loaded. However, there were much fewer resources available for landing tanks. Since 1938, the British Navy has produced the LCM Mark 1 (Landing Craft, Mechanised) or LCM-1 boat - with a displacement of 21 tons and a speed of 10 knots, it could take up to 16 tons of cargo (for example, a light tank) over a short distance.

Unloading an M2A4 light tank from a transport vehicle into the LCM-2 tank landing boat. Guadalcanal Island, August 1942. history.navy.mil

In the United States, since 1941, tank landing boats of their own design have been built, although with a unified designation - 45-foot LCM-2 with a displacement of 29 tons and a payload capacity of 14 tons. They were first used in August 1942 during the landing on Guadalcanal. In 1942, production began of the larger 50-foot LCM-3 with a total displacement of 52 tons, which could carry one tank weighing up to 30 tons - for example, the average M3 "Lee" / "Grant" weighing 28 tons; they were already afraid to load the new M4 Sherman tank, which weighed just over 30 tons.

Tank landing boats were loaded after launching. The dimensions of such vehicles (45–50 feet long and 14–15 feet wide) were still strictly limited by the dimensions of the ship's davits, so they could not accept heavy tanks.

The British fleet had three large tank landing transports (Misoa, Tasajero and Bachakuero), converted from 4800-ton shallow-draft Caribbean tankers intended for passage into Lake Maracaibo. All of them took part in Operation Torch. Each such transport could take on board about 20 medium tanks and over 200 infantrymen with weapons. Later, on their basis, tank landing transport LST (Landing Ship Tank) model Mk.1 was created, which in turn served as a model for the American LST-2.

British tank landing transport "Bachaquero" in the port of Bon, late 1942. Imperial War Museum

In addition, the American fleet had LVT-1 amphibious armored transporters, which had already proven themselves excellent on Guadalcanal. During Operation Torch, four such transporters were assigned to each coastal engineering company; such companies were engaged in supplying the landing forces and ensuring their actions, that is, the transporters were used only as vehicles.

Planning the operation

Disagreements began almost immediately within the Allied command. American General Dwight Eisenhower, appointed supreme commander of the entire operation, believed that the main landing should be carried out in French Morocco and Algeria, and the operation planning committee set the main goal of quickly occupying Tunisia in order to prevent the Germans from coming here. As a result, the first operation plan, presented on August 10, 1942, provided for simultaneous landings at four points: in Casablanca on the Atlantic coast, near the ports of Oran and Algiers, as well as in Bon (now Annaba) near the border with Tunisia. The objective of the operation was “to capture Tunisia in the shortest possible time and create a strike group in French Morocco capable of ensuring control over the Strait of Gibraltar.”

. At the same time, six British divisions landed in Bon and Algiers, and seven American divisions landed in Oran and Casablanca. Due to the impossibility of quickly concentrating such large forces, the operation had to be postponed until early November.

Route of Allied convoys from England for landing in North Africa from October 21 to November 7, 1942. S. W. Roskill. The War at Sea 1939-1945. Chapter XII (1953)

To speed up preparations for the landing and better concentrate forces, Eisenhower proposed slightly reducing its scale: on August 22, he presented to the US Chiefs of Staff a new plan, which excluded a landing at Casablanca - the operation would be carried out only in the Mediterranean Sea. According to this plan, two tank and five infantry divisions would land at Oran with the task of establishing control over western Algeria and French Morocco, and four infantry and two tank divisions would land at Algiers and in the Beaune area to occupy Tunisia and eastern Algeria. The operation was planned to begin on October 15, but Eisenhower himself said that, most likely, a later date would have to be set.

In any case, the most difficult task was considered to be the capture of Tunisia. According to the calculations of Eisenhower's headquarters, even from Bon to him the troops needed to travel 200 miles (320 km), and from Algeria - 400 miles (640 km) through terrain with an underdeveloped road network. The capacity of the Algerian port made it possible to unload two brigades a week here, and only one in Beaune. Thus, even in the absence of French resistance, two brigade groups could reach the area of Bizerte and Tunis only on the twelfth day of the operation, and tanks only on the fourteenth day. The arrival of another division could be expected within the next week.

The US Committee of Chiefs of Staff considered even these plans to be overly optimistic, and in the event of possible French resistance, completely unrealistic. Already on August 25, the committee put forward its own plan, according to which the landing of troops east of Oran, in Beaune and even in Algeria was canceled altogether. The ultimate goal of the operation did not change, but the immediate goal was only to occupy French Morocco and Western Algeria in order to create a solid base for further operations.

This plan was actively supported by the British Chiefs of Staff, although Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal demanded the rapid occupation of Tunisia, and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Alan Brooke, supported by Churchill, eventually insisted on landing in Algeria. Thus, Tunisia became only a further target for the ground offensive, and its capture required the landing of tank and motorized formations.

General plan for the Allied landings in North Africa. historicalresources.org

The landing was to be carried out by three task forces, one of which operated from the Atlantic, and two from the Mediterranean:

- The Western Task Force

(Casablanca), under the command of Major General George Patton, consisted of three American divisions: the 2nd Armored, and the 3rd and 9th Infantry. The total strength of the group was 35,000 people and about 250 tanks. The naval part of the operation was led by Rear Admiral Henry Hewitt (34th Task Force); - The Central Task Force

(Oran), under the command of Major General Lloyd Frydendall, consisted of four American divisions totaling 39,000 men. In the first echelon, the 1st Tank and 1st Infantry Divisions, as well as the 509th Parachute Battalion (a total of 18,500 people), landed. The naval part of the operation was led by Commodore Thomas Trowbridge; - The Eastern Task Force

(Algeria) had a mixed composition (60,000 American and 26,000 British soldiers) and was under the command of British Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson. Its basis was the 1st British Army of four divisions, but the first to land was the vanguard consisting of the 78th British and 34th American infantry divisions, the 1st and 6th battalions of the British “commandos” (in fact, two reinforced American regiments, two English brigade groups and two separate battalions with a total strength of 20,000 people). The naval part of the operation was led by Vice Admiral Harold Barrow.

The entire operation was carried out under the flag of the United States, not Great Britain, since the British seriously damaged relations with the French in 1940, first by attacking the fleet of the former ally in Oran and Mers el-Kebir (Operation Catapult), and then by sending French sailors to concentration camps, who did not want to join de Gaulle.

Tank formations for the landing operation

Two armored divisions of the American army were to take part in the operation: the 1st (Major General Orlando Ward) and the 2nd (Major General Ernst Harman), as well as one battalion from the 67th Tank Division, attached as reinforcement 3rd Infantry Division Western Group.

1st Armored Division

Old Ironsides was created on July 15, 1940 at Fort Knox. The core of the division, the 1st Armored Brigade, was reorganized from the 7th Cavalry Brigade, maintaining the same numbering of its units. However, the brigade itself was cavalry in name only: it was created in 1932 precisely as an experimental mechanized unit, although it included two old cavalry regiments of the American army (one was created in 1833, the other in 1901). Initially, the brigade also included the newly formed 69th Tank Regiment, but already in February 1942 it was transferred to the 6th Tank Division and operated in the Pacific Ocean.

Emblem of the 1st Armored Division. priorservice.com

In addition, the division included the 6th Infantry Regiment, one of the oldest American regiments, created back in 1812. Previously it was part of the 6th Infantry Division, in 1936 it was converted into a motorized division, and in 1939 it became separate. Already in April 1941, part of the regiment was transferred to form the 51st Infantry Regiment of the 4th Armored Division. The regiment had two battalions of four companies, a regimental group and an anti-tank company.

Finally, just before the landing in North Africa, the division was assigned the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion, armed with 75-mm T12/M3 self-propelled guns on the Autocar half-track truck chassis and 37-mm M6 Fargo anti-tank guns on the Dodge light truck chassis. "

By mid-1942, the division had more than 600 medium and light armored vehicles. Its structure was as follows:

- 1st Armored Brigade: 1st Armored Regiment (light vehicles), 13th Armored Regiment (light vehicles);

- 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion;

- 6th Infantry Regiment;

- 68th Artillery Regiment;

- 27th Field Artillery Battalion;

- 81st Armored Reconnaissance Squadron;

- 16th Engineer Battalion;

- 13th Supply Division;

- 19th Ammunition Battalion;

- 47th Medical Battalion;

- 141st communications company.

2nd Armored Division

Hell on Wheels was formed at Fort Benning on the same day as the 1st - July 15, 1940. Initially, it was formed as a “heavy” one: out of six tank battalions, four were armed with the new Sherman medium tanks, and only two with light Stuarts; most of the remaining American tank divisions were “light”, having only three tank battalions of four companies.

M4 Sherman medium tank in North Africa, early 1943. waralbum.ru

The division's tank brigade was commanded by Colonel George Patton; from November 1940 to April 1941, he was division commander with the rank of brigadier general. By the summer of 1942, the main composition of the division was as follows:

- 2nd Armored Brigade: 66th Armored Regiment, 67th Armored Regiment, 17th Armored Battalion;

- 41st Infantry Regiment;

- 14th Artillery Battalion;

- 78th Artillery Battalion;

- 92nd self-propelled artillery division;

- 82nd Armored Reconnaissance Battalion;

- 2nd Ammunition Division;

- 2nd Supply Division;

- 48th Medical Battalion;

- 142nd communications company.

Landing of the Western Task Force

The Western Task Force landed at dawn on November 8, 1942, at three points in French Morocco:

- Strike group TG 34.9

is in the center, near Fedal, slightly north of Casablanca. This was the strongest part of the landing: 18,783 people and 1,700 vehicles. Here, from 15 transports, the 3rd Infantry Division, the 1st Battalion of the 67th Tank Regiment and Battery A of the 78th Artillery Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division landed - a total of 79 light tanks and a number of self-propelled guns. In Casablanca itself, the landing was considered too dangerous due to the strong coastal defenses; - Strike group TG 34.8

- in the north, at the mouth of the Cebu River near Port-Lyotay. Here, 9099 people landed from 8 transports: the reinforced 60th Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division, the 1st Battalion of the 540th Engineer Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the 66th Tank Regiment of the 2nd Armored Division - a total of 65 light tanks; - Strike group TG 34.10

- in the south, near Safi. Here, 6,423 people landed from six transports: the 47th Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division, as well as the 2nd Battalion of the 67th Tank Regiment and two batteries (“C” and “B”) of the 78th Artillery Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division divisions - a total of 54 medium and 54 light tanks, as well as several dozen self-propelled guns.

Light tank M3 "General Stewart" in North Africa, early 1943. waralbum.ru

Each landing transport carried up to 50 boats of various types. The general landing scheme at all three points was as follows: reconnaissance boats were the first to go to the shore, whose teams had to establish a landing site, anchor outside the surf line and light infrared searchlights, as well as signal lights of the established colors. Then landing boats with troops were launched into the water - they formed the first wave of landing forces. Under the cover of a specially designated group of destroyers, these boats approached the shore at a distance of 4,000 feet, where they deployed in a line and at 4 o’clock in the morning began moving towards the shore, guided by light signals from reconnaissance boats. The landing was to take place at 4:15, after which the landing craft would return for further shipments of men and equipment.

Landing at Fedala

Due to lack of experience and unforeseen circumstances, the landing schedule was immediately disrupted, and the losses of the boats were unexpectedly high. Thus, in the Fedala area, of the 25 landing boats that were the first to move to the shore, 18 were out of action (mainly from holes in the rocks near the shore); of the 33 Jefferson transport boats, 17 remained in service after the landing of the first throw. In total, of the 347 landing boats of the Central Group, 40–45% were out of action, with the main loss occurring on the first day of landing. Unloading the tanks turned out to be especially difficult, for which a flat bank was required. Tank landing boats and amphibious tracked transporters often had to maneuver along the coast in search of a more convenient landing site.

Due to the unscheduled loss of landing craft, the landing was greatly delayed: in the Fedala area, 3,500 people landed ashore in the first hour of unloading, but by 17:00 their number only grew to 7,750. Nevertheless, by the night of November 9, Fedala harbor, coastal batteries and all the points outlined by the landing plan were captured, after which the unloading of soldiers and equipment (including tanks) began from transports already in the port. On November 10, American troops reached Casablanca.

Landing in French Morocco. S.E. Morison. American Navy in World War II: Operations in North African Waters

Landing at the mouth of Cebu

At the mouth of the Sebu River, the coast was mostly low-lying and more convenient for landing, and the coastal defense was much weaker, although it was carried out extremely skillfully and persistently. Moreover, on the first day of the landing, the French tried to attack the American bridgehead, using 32 Renault R-35 and Renault R-39 light tanks. Since on the first day the Americans managed to land only seven tanks, and then in the opposite place from the attack, the tank battle did not take place.

In general, the landing in this place was very delayed, and the second wave was never unloaded until the end of the fighting on November 11. Losses in the landing boats turned out to be as great as in Fedala: out of 161 boats, 70 (43%) were lost, and only 16 of them were able to be put back into service.

Landing at Safi

The port of Safi was chosen for the landing because it was possible to unload Sherman medium tanks from the Lakehurst transport directly onto the embankment, without using tank landing boats. Safi harbor was prepared by the French for defense (there were about 450 people with field artillery here), so the old destroyers Bernadou and Cole, converted into high-speed landing transports, were used to quickly capture it. Looking ahead, we note that thanks to unloading at the port, out of 121 landing craft deployed in the southern sector, only nine were damaged, and eight of them were later repaired.

As a result of the attack by the Bernado and Cole, the port was captured by noon, after which Lakehurst began unloading tanks onto the quay wall using ship cranes. In addition, the unloading of two batteries (“C” and “B”) of the 78th artillery battalion of the 2nd armored division, equipped with 105-mm T19 self-propelled guns on a half-track armored personnel carrier chassis, began here. By the night of November 8, the unloading was completed, and the 78th artillery division began advancing deeper into Moroccan territory. On November 9, self-propelled guns took up defensive positions, preparing to repel a French counterattack: according to aerial reconnaissance, a large enemy column was moving towards Safi from the direction of Marrakesh. However, the counterattack did not take place, and by the evening of November 9, the first Shermans of the 67th Tank Regiment reached the front line.

105-mm self-propelled gun T19 from the 93rd Tank-Artillery Battalion, 6th Armored Division during training in Arkansas, December 1942. vn-parabellum.com

Alas, the unloading of the tanks was delayed: all the vehicles were unloaded ashore only on November 10. After this, the tankers received orders to advance on Casablanca with the support of part of the 78th artillery division. However, by this time the trucks could not be unloaded, and one refueling for the entire march was not enough for the tanks. The naval command found an original solution: it sent the destroyer Cole with fuel to the port of Masagan, located south of Casablanca. The tankers were to capture Masagan and then refuel from a destroyer in the harbor. Masagan was occupied by tanks and self-propelled guns on the morning of November 11, by which time a message had arrived about the surrender of the French in Casablanca.

Results of the landing of the Western group

In all three places, the landing took place without preliminary bombardment of the coast: the Americans hoped that the French would surrender without a fight. Indeed, the day before, General Henri Betoir attempted a coup, trying to prevent resistance to the Americans, but his speech was suppressed and only alerted the French command, which was subordinate to the Vichy regime.

As a result, the French coastal artillery and fleet offered strong resistance to the Allies in the first hours of the landing. However, the hail of shells from American battleships and cruisers had not only a physical but also a psychological impact on the French: it became clear that the Americans had significantly superior forces. Under these conditions, the French soldiers and officers considered that their military duty had been fulfilled and began to surrender: in the Safi area this began by the evening of November 8. In Port-Lyautey, resistance continued until November 10, and Casablanca capitulated on the morning of November 11. In total, the French navy and ground forces lost 490 people killed and 969 wounded.

The unloading of the airborne troops personnel was completed by the evening of November 11. However, by this time only two-thirds of the transport and a quarter of the available supplies had been unloaded. The unloading was finally completed only a few days later.

Landing of the Central Group

The forces of the Central Group were to land on both sides of Oran: 30 km west of it on the beach of Les Andaluzes and 45 km east in the small harbor of Arzeu. The main goal of the landing was to capture the port of Oran and the military harbor of Mers el-Kebir lying next to it, as well as the airfields of La Senya and Tafaraoui located to the south. The latter were supposed to be captured with the help of tank units, as well as a group of five hundred paratroopers of the 509th Airborne Regiment.

Drop-off points in the Oran area. S.E. Morison. American Navy in World War II: Operations in North African Waters

Occupying bridgeheads

The 1st Regiment of the 1st Armored Division landed near Arzeu, where two British Maracaibo-class tank landing transports were used. The 13th Regiment of the Division was to land west of Oran in two places: on the beach of Les Andaluzes (“Coast Y”) and in Mersa Bou Zejar 30 km to the west (“Coast X”); at the last point, a third transport of the Maracaibo type was used. The landing in Arzeu was extremely successful: already on the night of November 8, the port was captured by two companies of the 1st battalion of American Rangers from the Royal Scotsman transport, after which other ships began to unload here.

At the same time, the main part of the landing force began landing at Saint-Leu, southeast of Arzeu, encountering weak enemy resistance. At dawn, after occupying the bridgehead, the tank landing transports "Misoa" and "Tasajero" arrived here, which by 8 o'clock in the morning were able to completely unload. Units of companies “B” and “C” from the 701st tank destroyer division, armed with T12/M3 self-propelled guns, were also landed here.

The rapid unloading of tanks directly onto the unequipped coast convinced the Allied command of the value of large tank landing transports. It was after this that they began to be actively built in England and the USA.

By the afternoon of November 8, French resistance in the Arzeu area was completely broken, and landing forces captured Saint-Claude and Ferus southwest of Arzeu. This made it possible to move the unloading of the second wave of transport directly to the Arzeu harbor.

The landing west of Oran took place without enemy opposition; the French offered the first resistance only at about 8 o'clock in the morning at Bu Sphere, when the soldiers of the 3rd Airborne Battalion began advancing towards Mers el-Kebir. The tank landing transport "Bachakuero" approached the shore in the Mersa Bou Zejera area at 4:15, however, due to the shallow depth, a pontoon bridge had to be built here to unload the tanks. Only by 9 o'clock in the morning were all the tanks unloaded onto the shore.

Tank battle for Tafaraoui airfield

By noon on November 8, two bridgeheads had been created on both sides of Oran, on each of which a mechanized strike force was concentrated: the eastern one was designated “Red”, the western one was designated “Green”. Subsequently, due to deteriorating weather, the unloading of troops and equipment on open beaches slowed down, and east of Arzeu stopped altogether. In addition, due to the insufficient number of LCM tank landing boats, the unloading of tanks and other equipment was very slow. Some of the planned areas in the “Green” sector turned out to be unsuitable for landing due to too shallow depths; in addition, there was confusion with equipment being unloaded in the wrong places where it was needed.

Nevertheless, by 11 o’clock on November 8, the American motorized units of the “Red” group, reinforced by a company of the 1st tank regiment and self-propelled guns of the 701st division, covered 50 km and reached the Tafarawi airfield. According to the original plan, the airfield was to be occupied by paratroopers of the 509th Airborne Regiment, but during the night landing they were scattered across the surrounding hills. As a result, tank crews had to take the airfield, and the French managed to scramble several planes: during air attacks, one Stuart tank was destroyed and three tank crews were wounded.

75-mm self-propelled gun T12/M3 on a half-track chassis. worldwarphotos.info

However, by 1 p.m., Tafaraoui airfield was occupied, with the Americans capturing about 300 prisoners and an artillery battery of seven guns. Already in the evening, Allied fighters from Gibraltar began to relocate here. On the same day, units of the “Green” group arriving from the west occupied the La Senya airfield (500 prisoners and 9 aircraft were captured).

By the end of November 9, Oran was completely surrounded. However, the French were not going to give up: in the morning they even tried to counterattack the Tafarawi airfield with the support of tanks, artillery and aircraft.

French tanks appeared to the east of the airfield, after which B Company of the 1st Tank Regiment, under the command of Captain William Tuck, moved towards them, accompanied by a platoon of tank destroyers of Lieutenant Whitsitt. Whitsitt's 75mm self-propelled guns opened fire from a hill about 700m from the village of Saint-Lucien, while Captain Tuck's tanks moved across the open ground towards the enemy, two platoons in front and one half a kilometer behind. French tanks of the rare Renault AMC-35 model opened fire, but from a long distance the shells of their 47-mm cannons (only 28 calibers long) did not penetrate the armor of American vehicles. At the same time, the 75 mm Sherman guns and the 37 mm long-barreled (53 caliber) Stuart guns hit the French tanks one after another.

French medium tank "Renault" AMC-35, knocked out in France in 1940. waralbum.ru

According to the report of the 1st Tank Regiment, 14 French tanks were destroyed in the battle for the airfield, two of which were chalked up by the 701st Anti-Tank Fighter Division. The Americans themselves irretrievably lost one light tank and one soldier. This was the first battle between American tankers and enemy tanks in World War II.

On the night of November 10, reinforcements from the “Red” group approached the Tafarawi airfield: two Shermans, five Stuarts and one self-propelled gun. That same morning, American tanks occupied the village of La Seina, south of Oran, and another Stuart was lost to artillery fire. At noon on November 10, the garrisons of Oran and Mers el-Kebir capitulated after negotiations.

Ahead - Tunisia

The first phase of Operation Torch was successfully completed. Next, the 1st Armored Division would advance to Tunisia; The 2nd Armored Division remained in reserve in the Rabat area until the end of December.

Further Allied advance into Tunisia, 11–17 November 1942. historicalresources.org

The remaining units of the 1st Armored Division (including the 6th Motorized Regiment and the 16th Engineer Battalion) were unloaded only on November 21, when the main forces of the division were already advancing on Tunisia. The remainder of the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion did not arrive until December 10th. Units and subunits of the 2nd Armored Division arrived even later: for example, the 92nd Artillery Division, armed with 105-mm Priest tracked self-propelled guns, was unloaded in Casablanca from the Thomas H. Barry transport only on December 24.

Literature:

- S. E. Morison. The American Navy in World War II: Operations in the waters of North Africa, October 1942-July 1943. M.: AST; St. Petersburg: Terra Fantastica, 2003

- M. Howard. Big strategy. August 1942-September 1943. M.: Voenizdat, 1980

- Harry Yeide. Tank Killers: A History of America's World War II Tank Destroyer force. Philadelphia & Newbury: Casemate Publishers, 2010

- https://macspics.homestead.com/History.html (Read About our History 1/1 Cav)

- https://www.3ad.org/unit-web-sites/armor-site/13th-cavalry-regiment

- https://www.69tharmor.com/regiment.html