Home » Real story » History of Wars » Throwing weapons of antiquity

History of Wars

admin 06/08/2019 10146

20

in Favoritesin Favoritesfrom Favorites 3

There is an opinion that throwing weapons are an invention of historians, that with the materials existing at that time, such machines are generally impossible to build. But there are quite workable modern reconstructions. I am not a supporter of either theory simply because each design must be approached separately. I am only presenting to you an attempt to systematize throwing weapons.

If you put together the names of throwing weapons of antiquity, you will get an impressive list of many dozens of terms (even if you do not take the exotic languages of the East). Palinton, onager, scorpion, angen, fundibul, espringal, robinet, mangonel, calabra... It doesn’t take long to get confused in all this splendor and decide that there are about as many types of siege weapons as there are varieties of swords. But this, of course, would be a mistake.

Operating principles of siege engines

All throwing machines, except the siphonophore, can be divided into three categories according to the force used to launch the projectile.

Tension machines work in the same way as a bow: by straightening, the machine's arm sends the projectile forward. This method is great, so to speak, “in small forms,” that is, for hand-held and light stationary weapons, but as the size increases, it turns out that it is very difficult to choose the right parameters for the bow. In addition, the bow often breaks in the process - with very, very unpleasant consequences. Tension machines are the lightest of all.

Torsion bar machines use a more cunning method. A lever is inserted into a bundle of stretched oxen tendons or ropes and rotated until it produces the required tension force. Then it is further turned by the charging mechanism, and when the lever is released, the force of the twisted wires sends the projectile. A torsion bar machine is a much more advanced and complex technology, but it provides significantly more possibilities.

It can be difficult to immediately imagine the operation of a torsion bar machine; but try stretching a regular rubber band between the fingers of both hands, inserting a pencil into it and twisting it. The principle will immediately become clear...

Finally, gravitational machines operate on normal gravity - that is, a counterweight launches the projectile. This design is justified only for the largest machines, when it becomes impossible to achieve the required force from the torsion bar circuit.

In fact, science knows only four types of pre-firearm throwing weapons (we exclude hand weapons - bows, crossbows, slings - from consideration). These are the catapult, ballista, trebuchet and siphonophore. And all these calabres, robins and onagers are simply varieties of the first three of them. Siphonophores were successfully used by only one people, and therefore cannot boast of an abundance of subspecies.

It often even turns out that the next “new type of siege weapon” is nothing more than the proper name given by the soldiers to their favorite ballista. Thus, in later times, the Italian condottieri called each bombard or cannon by name; throwing weapons of antiquity were less often awarded personal names, but it still happened...

Here it should be noted that ancient chroniclers and historians introduce considerable confusion into the classification of siege weapons. After all, it’s impossible not to mention the machines that threw stones during the legendary siege of such and such a fortress, but... the historian himself has never seen this machine. But he has a good idea (as it seems to him) of her externally and wants to convey this information to his descendants.

So miracle drawings appear, depicting a mechanism that no engineer in the world can make work. Polybius, for example, is especially famous for such pictures, who left us the most valuable information about Roman military science during the Punic Wars. Vegetius, a noble warrior, had great problems with proportions when drawing. And descendants wonder: what the hell did these ancients arm themselves with?

Another thing is Leonardo da Vinci: this one, undoubtedly, understood weapons and knew how to draw - God forbid to everyone. But here, too, bad luck: the great Tuscan had a very rich imagination and drew not only what was used in reality, but also what his own imagination invented. His devices work great, but it is not always possible to understand whether they were built in reality...

Sling

The sling is the oldest throwing weapon. The sling was most often made from a braided rope or a leather strap with an extension in the middle, where a stone was installed - a throwing projectile. A loop was made at one end of the strap, which was hooked onto the finger. During throwing, the other end was released and the sling unwound, throwing the projectile at the target.

Sling made of braided rope with a stone as a projectile

The story from the Old Testament about the giant warrior Goliath, a representative of the Felistine army, and the future king of Judea, David, is widely known. According to legend, David defeated the well-armed Goliath with a sling, hitting him in the forehead with a stone, and the Felistine army fled.

David and Goliath

A sling, compared to throwing a stone by hand, made it possible to accelerate the projectile to greater speed, and, therefore, give it greater kinetic energy. But the accuracy of throwing from such a weapon was low.

Ballista

A ballista throws arrows or stones in much the same way as a crossbow. The bowstring, tensioned by a special mechanism (a banal hook or a goat's leg is not enough here!), bends the ballista's shoulders, then it is released, and the shoulders, straightening, send a stone or arrow forward.

The word "ballista" comes from the Greek verb "ballein" - to throw, to throw.

Until the 4th century BC. the catapult was called a ballista, and the ballista was called a catapult. Then, due to some not entirely clear circumstances, the names changed owners. This confusion has pretty much spoiled the blood of historians!

Most ballistas do not have a single bow like a crossbow, but rather two separate arms. Often the arrow is sent not by the bend of the shoulder itself, but by another force: the shoulder is attached to a twisted rope. This is called a torsion machine. But there are also a lot of light tension ballistas.

The ballista is most often cocked with an ordinary collar, like a well collar, on which a rope with a hook is wound - the hook holds the bowstring. The hook designs were quite intricate - there was even something like a carabiner lock.

Among throwing weapons, ballistas are the lightest and most mobile. Therefore, it is not surprising that they were found on ships, and even in the “horse” version (like later horse artillery). Such devices were called carroballistas. (There were also mobile catapults, but they had to be pulled by a team of several oxen, and they could not be called truly “mobile.”

Carroballistas became an indispensable element in later Roman tactics: for example, Vegetius reports that each century is required to have one such machine, powered by 11 soldiers (hence, the legion carries with it 60 carroballistas).

There is a myth that ancient siege weapons were used only during assault. In fact, the Romans realized that ballista works wonders against large crowds of people, and they did not hesitate to use it even in an open field.

Another advantage of this weapon is its fairly high aiming ability. Experienced soldiers send cannonballs quite accurately from catapults, but they still need decent aiming. Some ballistas had two combat modes - targeted and long-range; in the latter version it was quite possible to hope for a 500-meter flight of the projectile! The record for the range of the ancient ballista is just over 700 meters. Aiming was achieved at much shorter distances - about 100 meters, maximum - 200.

The power of a shot of a ballista, of course, cannot compete with a catapult or trebuchet. But the arrow flies along a relatively flat trajectory, and you can try to hit it right at the gates of the fortress; but with a catapult core flying in a high arc, this can hardly be done.

Among the types of ballistas are:

Types of throwing machines

The history of siege engines began with Carthage, a Middle Eastern descendant of Phenicia. The Phoenicians built siege towers - this helped them in sieges of the Sicilian Greeks, and battering rams. Realizing that guns provided superiority to the enemy, Dionysius I, the ruler of Syracuse, himself acquired rams and even catapults, which helped him in siege warfare. To do this, he needed to gather craftsmen from all over the Mediterranean.

For conventional wars, siege weapons were unprofitable, because such machines were expensive to build, and they were difficult to handle. Machines were built for siege warfare. Therefore, when the sieges stopped for half a century, nothing was heard about cars either. They appeared again in Macedonia under Philip II. Polyidus of Thessaly and other masters of, as they were called, siege warfare traveled with him. He is said to have developed several modifications of rams and a huge siege tower, Elepolis, near Byzantium.

Alexander the Great inherited his father's experience. Some of his masters are also known to historians: Diad, a student of Polyidas, for example. He is known as the man who took Tyre from Macedon.

We know about ancient machines thanks to chroniclers. For example, Beaton described the siege tower created for Alexander the Great by Posidonius. Moreover, he described it very briefly, including in the story recommendations on the wood that is best used for construction. Historians have long debated whether Beaton's story was fiction. There were too many details in it, and the designs he described were actually used later, which suggests that Beaton did not invent anything.

Siege towers were not enough, because the same archers fired from them. Guns were needed that could launch heavy projectiles. Such a weapon no longer fit in his hands.

Ballistas

Ballista

Previously, the ballista and the catapult were called after each other. Then the names were changed. Why has not yet been clarified. But historians had to struggle a lot with these names. Translated from Greek, ballista means throwing, because the name comes from “ballein” - to throw. Nowadays, when we hear the word “ballista,” we imagine a weapon that shoots only arrows. But previously the ballista was not limited to this.

Meanwhile, the difference between a catapult and a ballista is that the ballista has two separate arms. Catapults have a single bow. A ballista is most often a torsion bar machine - a rope is tied to the shoulders and twisted. But there are also ballistae made as tension machines. They may have more than two shoulders; All of them have strings attached to them that stretch the projectile. With the force of four, or even six shoulders, the projectile flew forward.

A ballista works much the same as a crossbow. Its projectiles are stones and sometimes arrows. First, the bowstring is pulled, it bends the ballista's shoulders. You can’t just pull the string like a bow, you need a mechanism, which is like a well gate with a hook. Gates come in different shapes. Then the string is released and the projectile flies forward.

Among other advantages, the ballista allowed for fairly accurate aiming. It even had two shooting modes, accurate and long-range. In long-range mode, without much aiming, one could expect the projectile to fly five hundred, or even seven hundred meters. As for aiming... Of course, experienced soldiers could aim even from a catapult, but skill was required. And in the precision mode of the ballista, the projectile flew one hundred to two hundred meters with high accuracy without any problems.

At the same time, the advantage and disadvantage of a ballista compared to a catapult is its light projectiles. They couldn’t cause much damage, but they usually flew almost in a straight line, and the cannonballs of the catapults flew in a high arc.

Unlike catapults, which had to be moved with the help of oxen, ballistas are easy to transport, they weigh little - and therefore were often found on ships and even on horses and were called carroballistas. The Romans soon began to keep ballistae in their armies - one for every hundred soldiers, according to Vegetius. Of the hundred, eleven were powered by carroballista. There were sixty centuries in each legion, therefore sixty carroballistas.

The Romans knew that siege weapons were good not only against walls. They also work great against crowds. Therefore, it would be a mistake to claim that ballistas and other siege machines were used only for sieges.

Gastraphetes

This is the oldest Greek ballista - more precisely, a cross between a ballista and a crossbow. The name means "belly bow" in Greek. Gastraphetes imagines a crossbow so large that it is impossible to hold it in his hands, and therefore he is supported on the ground with a crutch, and the butt covers his stomach in a wide arc.

They were armed with such a miracle shortly before the Macedonian conquest, and Alexander’s army also had enough of them. But they were soon improved, and... appeared.

Arcballista

The Arcballista, also known as the Oxybel, is still a giant crossbow, a tension machine. But she already has a real machine and a big collar. The projectile is a special heavy arrow.

They also talk about a large arcballista, where the string was moved by six vertically placed bows. But this is most likely a myth: it is mainly the authors of the late Middle Ages who write about it, and they write about it as if it were from hoary antiquity, and there is no reason to believe that they knew what they were talking about.

Arcballista is by nature quite limited in its capabilities; and the point is not only in the tension scheme, but also in the lack of the ability to change the angle of the bed. This cuts the range down to about 40-60 meters; not serious!

As you know, David struck Goliath with a stone thrown from a sling. The thousand-year evolution of this simple weapon led to the creation of complex gravity-throwing machines, that is, those whose action is based on the use of gravity (they are also called baroballistic). The trebuchet is rightfully considered their king!

It did not escape the attention of the ancient slingers that the longer the arm with the sling, the further and stronger the stone flies. The lever is lengthening, we would say now. So someone once thought of attaching a sling to a stick - one end of it is firmly fixed, the other, ending in a loop, is put on a nail driven in nearby (it is called a “tooth”). In the initial position, when the shooter holds the sling thrower horizontally to the ground, the free end of the hanging sling is held on the prong, but during the swing, when the stick reaches a vertical position, the overtaking sling overtakes it and slides off the prong, opens - and the stone flies out of the sling bag to the side enemy. In addition to lengthening the lever, the swing can be strengthened in another way: for example, it can be performed with both hands at once and in one movement instead of repeatedly spinning a regular sling. Accuracy decreases, but strength and efficiency increase significantly.

The sling thrower was invented simultaneously in different parts of the world - both in the Far East, and in the Late Roman Empire, where it was known from the 4th century under the name “fustibal”, and even in pre-Columbian America. In Europe, it lasted until the end of the 14th century, finding especially wide use in the siege of fortresses and on ships.

In China in the 5th–4th centuries BC. the stick with the sling was significantly increased in size and mounted on a pole with a slingshot or ring on top. A traction rope was attached to the free end of the throwing arm. In the initial position, the sling with the projectile was lowered to the ground, and the traction end of the throwing lever was raised up. The shooter sharply pulled the traction rope, the throwing arm of the lever soared up, the sling overflowed, opened, and the projectile flew forward. The device turned from a wearable device into a stationary one; the accuracy did not increase, but the power increased. Especially when they began to attach something like a brush to the traction end, and not one, but many traction ropes to it. Ten shooters could launch a heavy stone without much effort - after all, the throwing beam lay on a support post. The easel sling thrower was used mainly during siege and defense of fortifications.

For almost a thousand years, this invention did not leave China. In Europe, more precisely, in Byzantium and surrounding lands, it was first recorded in the 580s under the name “petrobolus,” that is, stone thrower. How it got there is not clear. At the beginning of the 7th century, petroboles were widely used not only by the Byzantines, but also by the Avars and Slavs, the Persians, and a little later by the Arabs and Visigoths. They soon pushed back the ballistas and catapults of the ancient style. Now in Byzantium they were called mangans, from where the Arabic “al-manjanik” and the Western European “mangonel” originated.

In the early Middle Ages, the Arab Caliphate was a major consumer of complex siege technology - its expansion was facilitated not only by light cavalry, but also by vehicles that rained down a hail of stones on enemy fortifications, and, from the 670s, pots with petroleum-based compounds. The Arab-Byzantine wars led to another improvement at the beginning of the 8th century - the appearance of a hybrid trebuchet. In a hybrid trebuchet (called a bricolette in France), the short thrust arm of the throwing arm is equipped with a small counterweight that balances the longer throwing arm. This makes the work of the traction team easier and allows larger vehicles to be made, and shooting becomes more accurate.

In the early 800s, traction trebuchets were adopted from the Arabs by the Franks, in the 10th century they reached Germany, around 1100 - Poland, in 1134 they were first recorded in Denmark, where they were used until the end of the 14th century.

The traction trebuchet had a significant impact on the tactics of defense and siege of fortresses, since it made it possible to use the entire civilian population in a firefight. The attacker could knock down the wooden fortifications along with the defenders from the walls and ramparts with a hail of stones, or create fires in the city with pots of flammable mixtures. The defenders could discourage those going on the assault and set fire to their siege works. And this is not a theory - for example, the leader of the Albigensian crusade, Simon de Montfort, died under the walls of Toulouse in 1218 from a stone thrown from a hand trebuchet by Toulouse women.

However, the traction trebuchet could not break the stone fortifications, even their battlements and parapets. Attempts to use hundreds of traction ropes created organizational difficulties, but did not solve the problem - in order to break through a stone wall, you need to repeatedly hit the same area. As a result, the traction stone thrower remained primarily an anti-personnel weapon.

The solution was found in the 12th century in the Eastern Mediterranean, most likely in Byzantium, although many thought about it. The proof is the treatise of Murda at-Tarsusi, who lived in Alexandria in the last third of the 12th century. The so-called “Persian manjanik” of al-Tarsusi still retains the proportions of a traction trebuchet, but the traction command in it is replaced by a net filled with stones. Moreover, this counterweight had to be lowered into a deep hole, which had to be dug in advance. In addition to throwing a stone weighing more than 100 kg, the counterweight pulled a heavy crossbow. A winch had to be used to lift the counterweight.

But the counterweight trebuchet was improved most quickly in Catholic Europe. During the siege of Acre by the Third Crusade in 1189–1191, huge trebuchets were used by both sides, and the Franks were able to destroy part of the powerful city wall after a long bombardment. This was something new in siege technology - previously stone walls could only be destroyed with a battering ram. In the 13th century, the trebuchet with a counterweight (it was also called frontibola, in Germany blida, in Rus' vice, there were other names) was widely used throughout Western Europe and quickly reached perfection. In 1212 it appeared in Germany, in 1216 - in England, by the beginning of the 1230s - in Rus'. Finally, in 1276, Muslim sources recorded its appearance in China under the characteristic name “Frankish manjanik”.

For some time, two types of trebuchet coexisted - with a fixed and with a suspended counterweight. The first is simpler in design, which was very important in the Middle Ages.

Gradually the disadvantages of a fixed counterweight became apparent. It had to be made solid, usually from expensive lead, since the contents of a loosely filled box or bag would roll when the counterweight fell. In addition, a fixed counterweight tends to swing for a long time after firing and violently shake the supporting structure. The optimal design is one with a suspended counterweight, which quickly stabilizes after the shot. It is an ordinary box filled with any available materials (earth, sand, stones), and its weight can be easily changed.

A large battered trebuchet is designed to throw stone cannonballs weighing 100–150 kg, that is, with a diameter of 40–50 cm, over a distance of at least 150–200 m. This weight of the cannonball is the optimal compromise between impact power and the convenience of hewing by hand and carrying on a stretcher. The 200m range still allows for accurate shooting, but eliminates the need to place the vehicle in the target archery range and overcome external fortifications (ditches and ramparts). From these basic requirements, known from medieval written sources, the dimensions of the machine follow - a throwing arm 10–12 m long, a support stand about 7 m high, a counterweight of about 10–15 tons. A team of 40 semi-skilled carpenters under the supervision of an experienced ingeniator (a master in the manufacture and use of trebuchets) builds a battered trebuchet from oak beams in ten days; an experienced mason hews one core in 5–6 hours. A properly built and sighted vehicle is capable of consistently hitting a 5x5 m square with a rate of fire of about two shots per hour. As a result, in a few hours a hole is made in a two-meter granite wall, standard for castles of the 13th–14th centuries.

The design of a trebuchet is simple and obvious - any skilled person can build a small model and verify its functionality (they dabbled in this already in the late Middle Ages). But there are also secrets. The ideal ratio between the counterweight and throwing arms of the lever should be 5.5:1. The sling should be as long as possible, but not touch the ground after leaving the trench where it is placed before launch. The strength of the entire wooden structure and sling is very important - only an experienced craftsman can find a compromise between saving materials and durability. The axes of the counterweight and throwing lever are lubricated with pork fat for ease of rotation. The prong must be strong enough, but capable of bending or changing length - the moment of opening of the sling and, consequently, the trajectory of the projectile depends on its inclination and length. However, the vertical aiming can be changed by changing the length of the sling (to do this, you can make a set of loops on it instead of one), as well as the weight of the counterweight, although the latter method is more crude. Horizontal aiming is carried out by hooking the frame with a crowbar. Since the machine is difficult to move in this way (even with the counterweight unloaded it weighs seven tons), it is better to immediately build it in the right place. It is important to consider the design of the trigger device (there are several suitable types of locks), safety precautions depend on this. The design of the gate can also be different - some will prefer a vertical gate, others a horizontal capstan, and for large cars “squirrel wheels” are especially popular (the larger the diameter of the gate, the higher the gear ratio).

Although the counterweight trebuchet is derived from the traction trebuchet, they are fundamentally different. The efficiency of a counterweighted trebuchet is much higher since it can use a maximum sling length. It also saves human resources. Its propulsion, that is, the counterweight, does not impose restrictions on power - it is possible to throw projectiles even weighing a ton. The main thing is that predictable shooting is possible from a trebuchet with a counterweight.

Note that shooting from a trebuchet is not “accurate” in the strict sense. A large trebuchet cannot be aimed to reliably hit the target with the first shot. This is the first gun in history to fire in an “artillery” manner, that is, “grab in a fork.” The first shot can only be calculated approximately (for this it is advisable to have geometric knowledge), but the roughness of the design will in any case cause a large error. Then the horizontal angle and steepness of the trajectory are adjusted, misses are reduced, and finally the target is covered, after which repeated shots can be fired from the found optimal position until the final result.

At the same time, using the gate to lift the counterweight sharply reduces the rate of fire. Therefore, it is advantageous to use a large trebuchet only against large, strong, stationary targets - for the destruction of walls, houses, enemy throwing machines, rams, siege towers. Another advantage is the ability to throw projectiles of any size and shape, including living and dead prisoners, various carrion for the transmission of infectious diseases, etc.

Today the design of a medieval trebuchet seems simple and obvious to us, but for a person of that time it was not so. It was necessary to curb, to prudently use such a force that he had never subjugated before. Not a single torsion catapult can even come close to the instantly released energy of a 20-ton counterweight falling from a height of 5–10 m. For medieval people, this was akin to the conquest of nuclear energy.

Such a heavy device was not easy to make, very difficult to move, and carefully hewn and weighed kernels were not cheap. The choice of the optimal design and the most vulnerable spot in the wall being broken, the preliminary calculation of the firing trajectory, linking the trajectory with the weight of the projectile, the counterweight, the length of the sling, and the inclination of the prong were very important. Any mistake was costly, but the results were appreciated. Previously, it was necessary to fill up the ditch, make an embankment against the wall, drag a heavy ram close and hammer it for a long time under a hail of blocks, logs and streams of burning resin poured from above. Hundreds and thousands of people worked for months and not always successfully. Now about a hundred people coped with the same task in a couple of weeks and without much risk.

Later, the word “engineer” came from the word “ingeniator”. The study of the counterweight trebuchet gave rise to the first medieval attempts to think about the concepts of gravity and force vector.

Whatever a step forward the battering trebuchet was, already in the 1330s it began to lag behind the development of defense. The walls of the fortresses became thicker, and most importantly, the technique of counter-battery warfare developed - light defensive trebuchets were faster-firing and smashed heavy siege engines even before they had time to make a breach in the wall. The era of gunpowder artillery began. Bombards finally took over in Europe in the 1420s. For some time, trebuchets were still used to throw incendiary shells with a canopy, but then mortars took over this role. The last example of the use of trebuchets in Europe dates back to 1487 (the Spanish siege of the Moorish Malaga). But in Central Asia in the Kokand Khanate they held out until 1808!

Now this device, as simple as it is ingenious, amuses reenactors of all stripes. It's hard to think of another way to experience all the delights of artillery with such little cost and effort.

The main advantage of the traction sling thrower was its exceptional ease of manufacture and use. You only need to have ropes and a few small, simple metal parts with you; a moderately skilled carpenter can make everything else on site in a matter of hours. Stones or pots of resin are used for throwing. Even women and old people can pull ropes. The minimum skill is required only from the gunner - a warrior who hangs on the sling before launching, orienting it in the horizontal plane. Modern enthusiasts manage to throw up to 1000 cobblestones per hour, and a rate of fire of 10 rounds per minute is considered normal. This is comparable to the rate of fire of an experienced archer. This weapon can be fired with a canopy, which allows you to throw shells over the fortress walls.

At the same time, there is no need to talk about any accuracy; shooting is carried out only approximately in the direction of the target at a distance of 50–100 meters. Moreover, these disadvantages are natural for a traction trebuchet - it is impossible to ensure that the traction command fires each shot at the same speed. In China, they used machines with 125 traction ropes for two people each, launching 60-kilogram stones, but they also fired no further than 70–80 meters.

Palinton and Scorpio

Palinton

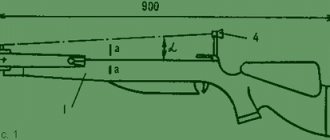

A palinton is a two-armed torsion ballista that throws stones (sometimes all stone throwers are called palintons, based on the origin of the word). The cores into which the lever arms are inserted are fixed on a rigid rectangular wooden frame.

The pallet was mounted on a clever tripod, which made it possible to rotate and tilt the gun, quite accurately fixing the angle. This same tripod allows you to overcome the main drawback of the arcballista and provides the weapon with a firing range measured in hundreds of meters.

Scorpion

Scorpio differs from palinton in that it throws arrows, not stones; Otherwise, the structure of the machine has not changed. It is also called eutiton (literally “arrow thrower”). Heron subsequently tried to improve the scorpion by making his own design, the cheiroballista; it didn’t really catch on, but it gave rise to a whole family of crossbows.

Palinton and scorpion are the two main ballista designs that have existed for over a thousand years. Their popularity lasted until the 14th century, and in some places longer.

Catapults and mechanisms from ancient throwing machines in modern technology

As we have already written, the term “catapult” in ancient Rome in written sources began to collectively refer to a wide range of throwing devices that were used mainly for military purposes. But even now catapults are widely used by the military. After all, it is not necessary to throw stones or arrows.

Thus, launch catapults began to be widely used on aircraft carriers in the first half of the 20th century to accelerate carrier-based aircraft to flight speed. Such work was carried out by all industrialized powers. In the USSR in the 1930s, experimental work was also carried out on launching seaplanes from short acceleration platforms. But the plane could no longer land back on such a ship.

Takeoff of the ship's reconnaissance seaplane KR-1 using a pneumatic catapult from the Soviet battleship Paris Commune. 1930—1933

American seaplane taking off using a catapult from the deck of an aircraft carrier

Let's look at the modern design of the launch catapult - the landing gear of the aircraft clings to a hook, which is accelerated using a cable and a steam engine. This photo shows a steam plume trailing behind the fighter.

American fighter taking off using a steam catapult

Small reconnaissance drones are launched using launch catapults. They do not need a special runway to take off, and they land, as a rule, by parachute.

This photo shows an example of preparations for the launch of the Orlan-10 UAV. As you can see, the drone starts from the guide rail using an elastic rope (you can’t call it an elastic band).

Launch of the Orlan-10 UAV

The Kalashnikov Concern produces drones that can be launched without a guide - like from a slingshot. For example, this is how the Zala UAV model is ejected directly from the hands of a military man.

Launch of the ZALA UAV

An elastic element such as a torsion bar , which began to be used in Ancient Greece in eutitons, palintons and onagers, has been widely used in the devices of some machines since the 20th century. For example, in the suspension of tanks.

Tank torsion bar - a long and torsionally elastic steel rod

Torsion bars are even used in passenger car suspensions. Here is an example of such a design.

Car torsion bar suspension

Polyball

The dream of making a weapon that shoots quickly has existed since ancient times, and almost every shooting thing had its own Gatling or Maxim. The rapid-fire crossbow was born in the East, but the rapid-fire ballista was born in Alexandria, and even the author of the idea is known - the well-known Dionysius.

The polyball (also known as polybolos) has two original parts: a mechanism for arrows, approximately the same as in the cho-ko-nu crossbow, and a gear wheel that cocks the bowstring (its invention is often mistakenly attributed to Leonardo da Vinci). Of course, one cannot count on truly great power from such a weapon; Probably, this and manufacturing difficulties were the reason why the polyball never became a mass machine.

Classification of throwing weapons

All throwing weapons can be divided into two large classes:

- The first includes weapons that hit a target using human muscle power;

- The second class includes those types of weapons that hit the target with a projectile, while the weapon itself remains in the hands of its owner.

This classification classifies all spears, axes, knives, clubs and other similar weapons as first class. The second class, according to the classification, is represented by bows, crossbows and throwing machines. In addition to these two groups, this classification identifies an intermediate group, which includes the sling.

Catapult

The catapult has a large lever, one end of which is attached to the axis, the other is free. The free end is equipped with either a spoon or a “basket” on ropes like a sling (it is often called a sling); a projectile is placed in this spoon or basket - usually a large stone or, less often, a special cannonball (in some places clay jugs with Greek fire were also used).

Most catapults are powered this way. The axle to which the lever is attached is attached to bundles of strands or ropes (torsion method) and twisted almost to the limit; The collar pulls the lever down, twisting the ropes even more. Then the lever is released and it sends the cannonball flying.

The projectile, naturally, flies along a hinged trajectory, the accuracy is moderate, but it is easy to throw it over the wall. The mass of the projectile is 20-40 kilograms, sometimes even up to 50-60.

The word “catapult” was originally the same root as “ballista”, although you wouldn’t guess it from its current sound. “Kata” means “against”, “to fight something”, and “remote” is the same corruption of “ballein”, that is, “to throw”.

The typical range of a catapult is about 300-350 meters.

Sometimes these machines were assembled right on the spot from trees found right there (they only took metal parts and ropes with them). The Romans, however, preferred to carry catapults with them as heavy artillery (ballistas were light). But it was impossible to ride them quickly on horses - they harnessed the bulls, as in the 19th century, to siege cannons. And the legion relied on only 10 catapults. Cars were often transported disassembled.

The main purpose of the catapult during an assault is to attack walls and towers (the ballista can select smaller targets, but will not break through a serious wall). It was usually placed on the fortress wall to fight siege towers - you cannot find a better tool. Catapults were also used in the navy - primarily for throwing Greek fire, until a better way was found. The ship is too nimble a target for a slow-cocking, slow-aiming catapult.

Firing from this vehicle is much more difficult than from a ballista, and qualified artillerymen were highly valued.

In the Middle Ages, the catapult replaced the ballista because 300-350 meters was both its maximum and target range. And this is greater than the flight distance of an arrow from an English bow or a Genoese crossbow fired from the height of a castle wall. Which became the decisive advantage. However, complete displacement did not happen.

Trebuchet (trebuchet)

A trebuchet (from the French Trébuchet - “scales with a yoke”) is an ancient throwing machine for throwing stones and other projectiles using a system of levers and slings. Perhaps the first prototype of the trebuchet was a sling tied to a long stick and thrown from the hand. According to the ancient Greek classification, such devices could be classified as palintons.

Trebuchets did not have elastic elements. The source of energy was either muscle force when it was necessary to pull a lever using a rope, or the potential energy of a lifted load. The higher and heavier the counterweight was, the more powerful the throwing machine was.

According to historical sources, the first trebuchet-like structures were used in Ancient China around the 5th century BC. In Europe, trebuchets were used during the Crusades and during the siege of cities in civil wars. In Rus', such throwing machines were called vices.

The first trebuchets were manual - a person or several people pulled ropes tied to a short lever.

Byzantine hand-held siege stone thrower (trebuchet)

Gravity trebuchets had a weight suspended from a short lever. The load could be stationary or swinging. A sling was tied to the end of the throwing lever. The weight of the cargo could reach 8 tons, and the shells - up to 400 kilograms. For throwing, projectiles were usually made of stone, round in shape and of the same mass to make shooting more accurate.

Michel Rotwiler. Heavy gravity siege trebuchet. 1459

Not a single trebuchet has survived to this day. And all modern reconstructions were made based on paintings and rather vague descriptions of ancient chroniclers, who, as a rule, had nothing to do with technology.

Reconstruction of a trebuchet near the Chateau de Beau in France

Modern reconstruction of the trebuchet "Middelaldercentret"

Onager

The onager is the most popular catapult of ancient Rome. Its only peculiarity is a basket on ropes instead of a spoon, which is more common in Greece.

The word "onager" means "wild ass". There are at least three versions about why the catapult was equated to a donkey. According to the first, the wild ass drives away predators by throwing stones at them with its hind hooves. This phenomenon is unknown to modern zoology, but the ancients had strange views about the behavior of animals... The second version claims that the catapult lever shoots up like the leg of a kicking donkey; Associations are an individual matter, of course, but the comparison is very strange. Finally, the third version, relatively plausible, says that the device worked with a heartbreaking creak, reminiscent of a donkey's cry.

The fighting donkey survived into the Middle Ages; however, there he acquired the nickname “Mangonel”. Over the years, the machine shredded, but learned to shoot something like buckshot; invaluable against dense formations!

Espringal

Quite a rare combat vehicle: a catapult based on the tension principle. Its lever is elastic, the collar bends it, and the lever, straightening, throws the stone (it is placed in a bag or basket). Apparently, the most successful scheme belongs to Leonardo, but we find the first known example in Flavius Vegetius.

Making espringal (also known as springald) is difficult; it is inferior in strength to an onager; True, it’s quite long-range. There is also the advantage that espringal almost does not need to be shot after installation. But still, these devices have never been very popular.

There was also an arrow thrower based on the same principle - it was called a brekol. They say that at 300 steps he pierced through a 15-centimeter log, but in fact he launched an arrow at 1300 steps. True, these statements are very doubtful.

Trebuchet

This achievement is no longer ancient, but medieval thought: it appears only in the 12th century, at the end of the era of pre-firearms. The word means in Old French "to throw over something." In Latin the same unit is called a frundibulum, in Italian a frontibola.

Gradually, the fortification improved, and locks began to appear that could be hammered with an ordinary catapult for almost years. And the need arose for more powerful weapons. Which was satisfied by the unknown French inventor.

(According to another version, the trebuchet was first invented in the East, and then through the Persians, Arabs and Byzantines the device arrived in Europe. But this idea was not confirmed; among other things, Byzantium recognized this machine clearly later than France. It even got to the point that the carriers they tried to declare ideas... our ancestors, the Varangians and Slavs. But even here it doesn’t work: the Varangian fighting machine is certainly not a trebuchet.)

Trebuchet contains no flexible elements at all. This is a gravity machine: the lever is driven by a counterweight.

For such a system to provide an advantage over a torsion bar system, a truly gigantic scale is needed; That's how it was. The lightest trebuchet counterweight pulled 400-500 kilograms, and sometimes a ton or two. Well, the projectile, of course... 150 kilograms - this trebuchet has only just begun. Later machines were capable of throwing, for example, a dead horse - and this is already half a ton. The record for the mass of a projectile that your humble servant has ever read about is 630 kg! The range is slightly superior to a catapult: 350-420 meters.

It is often said that during a siege, dead horses were thrown into fortresses for the sake of psychological effect. As for me, this is quite doubtful even for the sake of epidemics.

A medieval city dweller would not be embarrassed by the sight of a horse carcass. But since many people persistently denied the people of those times the right to imagine what spreads the infection, they came up with such a motivation, contrary to all evidence. Of course, psychic attacks also happened - then they threw the bodies of ambassadors or hostages, and Allaudin Khilji, during the storming of Delhi, threw bags of gold at the enemy fortress.

The power of the shot had to be paid for, firstly, by the bulkiness of the device (the lever is 20 meters long, other sizes are easy to imagine), and secondly, by a very long reload. It is very difficult to lift a couple of tons to the required height! One of the ingenious solutions successfully used by the French is a pair of “squirrel wheels”, inside which people – hundreds of people – are running.

Of course, using a trebuchet other than against fortress walls is extremely difficult - it takes a very long time to aim and shoot.

A highly simplified analogue of a trebuchet, without a counterweight, driven by simple muscular force, is called a perrier.

There are several types of ballistae

Gastraphetes

Gastraphetes

If you mix a ballista and a crossbow, you get a very large crossbow. So big that you can no longer shoot it from your hands. This is exactly what gastraphetus or, in other words, abdominal onion is. To shoot from a gastraphetus, it is supported on the ground with a crutch, while the butt is wrapped around the stomach. The belly bow was popular before the march of Alexander the Great, and gastraphetes were also used in his army. Then it was improved, and gastraphetes gave way to arcballista.

Arcballista

Arcballista

Another name for arcballista is oxybel. Like gastraphetes, oxybel is a tension machine, but it has a large gate and machine. She shot the arcballist with heavy arrows suitable specifically for this weapon.

Since the arcballista is still a tension machine, it is quite limited. It was also impossible to change the angle of inclination. The range of such weapons was reduced to forty to sixty meters. Not a very good result for a weapon, when compared even with the most ordinary ballista.

Some works by medieval authors talk about a very large arcballista, the string of which moved more than five bows. It is doubtful that such a machine actually existed, and the authors also talked about it as an ancient mechanism.

Palinton

Palinton

Palinton is already a torsion bar car. She throws stones. The word means “stone thrower,” which is why all stone throwers are sometimes called that. The palinton mechanism is a rectangular frame on which ox sinews are attached. This frame was mounted on a tripod, which made it possible to change the angle of inclination and, most importantly, secure it. Thus, the palinton was already more powerful and functional than the arcballista.

Scorpion

Scorpion

Scorpio is also called euthyton - arrow-thrower. However, it differs from the palinton only in this way - otherwise the device is the same. Heron tried to improve it and made a cheiroballista, but it never became widespread. But on its basis, many ballistas were built. However, it was the palinton and eutiton that were the main ballista designs, and served for a whole millennium.

Polyball

Polyball

The polyball is the embodiment of the dream of a weapon that would fire quickly. While the rapid-fire crossbow was being invented in the East, the ballista was being improved in Alexandria. This is how polyball was born. Among the things that underwent major changes were the mechanism for the arrows and the gear wheel. The wheel was used to erect a bowstring, and sometimes they say that Leonardo da Vinci invented it, but this is not so: the author of the polyball was Dionysius.

Polyball never became a powerful weapon, and therefore did not become widespread.

Catapult

Catapult

A catapult is a tension machine. On one side it has a spoon or “sling” (basket on ropes) for projectiles, and the other end is fixed to an axis. This axis is pulled down using ropes or sinews. They are stretched to the limit using a collar. Then the collar is released and the spoon or basket flies in an arc, imparting speed to the projectile.

The projectile most often became stones and special cannonballs. Sometimes jugs of Greek fire were launched into flight this way. Launched from a catapult, it flew in a suspended arc. Such weapons were not accurate, but the shells flew over walls. Usually from twenty to forty kilograms were sent into flight, but sometimes the shells reached sixty kilograms. These shells flew three to three hundred fifty meters.

The catapult is so easy to manufacture that sometimes the Romans assembled it from the forest found at the stopping place, transporting only metal parts. But most often they still carried 10 catapults with them in the legion, or transported them in parts. The catapult is heavy for horses - they harnessed oxen. The Romans needed catapults mainly for breaking through walls. Accuracy in this matter was not a decisive factor - the ballistas focused on smaller targets. During the defense of the fortress, catapults also came in handy; they were used to shoot at siege towers. At sea, Greek fire was thrown from catapults, but it was not until the siphonophore was invented. It was not very convenient to shoot from a catapult at ships, because they were moving quickly. But catapults for some time were much preferable to ballistas, because their three hundred to three hundred fifty meters were also accurate. No bow could shoot that far. The impact force of a catapult is also much greater. But they failed to completely replace the ballistae.

Oddly enough, catapult is originally a word with the same root as balliste. “Kata” means “against”, and “remote”, oddly enough, is a completely distorted “ballein”.

The catapult has fewer varieties than the ballista, and only one was popular, but still they all deserve attention.

Onager

Onager

The onager was the most common among all the catapults of Ancient Rome. He had a basket at the end of the lever, while Greece preferred a spoon. The onager was popular for quite a long time, until the Middle Ages, and changed its name to “mangonel”. The shells sent by him were crushed and became something like buckshot. Small shells were successfully used against foot and cavalry armies.

"Onager" means wild ass. This strange comparison for a weapon has three explanations, and from them you can choose any one you like.

According to the most plausible version, the onager creaked so much that it resembled the cry of a wild donkey. Surely this nickname was given by the soldiers who had to listen to this creak.

According to the most fabulous version, a wild donkey drives away enemies by knocking stones out of the soil, and this is similar to the principle of operation of the onager. According to zoology, donkeys do not do this at all, but in a country where it is easier to meet a god on the streets than a man, such an explanation, of course, could take root.

And the latest version says that the onager flies upward like the leg of a kicking donkey. It is somewhat similar to the first one.

Espringal

Espringal

Unlike other catapults that use the torsion principle, the espringal, or springald, is a tension machine. It has a flexible lever, and the collar bends it. When the gate is released, the springald shoots. Espringali has several disadvantages: it is difficult to make and is inferior in strength to the onager. But the range is higher and zeroing is practically not necessary. But despite this, espringal never became popular. This machine was known even under Flafia Vegetia, and the hand of Leonardo da Vinci most likely belongs to its most successful model.

Bricol

Bricol

Bricol threw arrows. They said that he was strong enough to break through a fifteen-centimeter-thick tree at a distance of three hundred paces. And he shoots even at one thousand three hundred steps. Whether this is true or not, we are unlikely to ever know.

Trebuchet

Trebuchet

The trebuchet, otherwise known as the frundibul, was invented already in the Middle Ages, and not in antiquity, shortly before firearms were invented. This is a gravity machine. "Trebuchet" means "throw over" in French. It does not contain flexible elements - instead, the projectile is driven by a counterweight falling on the other side of the lever axis.

The counterweight must be large for the projectile to fly effectively. With the help of a trebuchet, 100-150 kilograms of weight were sent towards the enemy, and gradually the weight of the shells increased. The counterweights that ensured the flight, of course, had to be two to three times larger.

The shells weighed half a ton. And they threw not only stones and cannonballs. Sometimes dead horses were sent behind the wall. They flew well - three hundred fifty to four hundred meters. Historians suggest that they tried to demoralize the besieged with horses, but it is unlikely that in the Middle Ages it was possible to frighten anyone with the corpse of a horse. This version is supported by the fact that people thought that horses would carry the infection and therefore were afraid. Sometimes they threw in ambassadors or hostages - to intimidate. And Allaudin Khilji, storming Delhi, even threw bags of gold.

Among other things, the trebuchet is a huge, long-recharging structure. The lever alone took up twenty meters. As for reloading, it was not so easy to carry and lift heavy counterweights. However, the French found a solution to this annoying problem - they built some kind of wheels for squirrels, only instead of squirrels, hundreds of people ran there, raising a counterweight.

The need for a trebuchet arose when the walls became too strong for ballistae and catapults. You could hammer them for years and not achieve any effect. It was necessary to throw heavier charges. And even though you can’t really aim with a trebuchet, it was convenient to use against walls.

According to one version, the trebuchet was invented by an unknown Frenchman. However, other historians say that the authorship of the mechanism belongs to the East. There are discrepancies in this version about how the trebuchet got to France. Sometimes they say that through the Persians, Arabs and Byzantines. But there is evidence indicating that Byzantium learned about the trebuchet much later. This is how the second assumption was born, according to which the idea was transferred by the Varangians and Slavs... but the Varangians, for example, used completely different combat vehicles.

Trebuchet has only one variety called perrier. Perrier is simpler than a trebuchet, and is launched not by a counterweight, but simply by human forces.

Siphonophore

Siphonophore

The most fantastic weapon of Byzantium is perhaps the siphonophore. It can hardly be called non-fire, because the siphonophore shoots with Greek fire. In a sense, a siphonophore or, as it is sometimes called, a siphon, is an ancient Byzantine flamethrower.

It was used at sea and provided Byzantium with an advantage over other countries. The siphonophore was not valuable at all for the strength or accuracy of the blow. Medieval galleys were nimble and small, unsuitable for aiming with catapults and other large machines. The same can be said about Slavic or Varangian boats. But the siphonophore sprayed fire instead of single shots. Whatever did not hit the target rotted in the water, and the falling drops set the ships on fire. Therefore, the siphonophore was mainly suitable for naval battles.

Whether the information about the siphonophore is true is unknown. No one still knows exactly what Greek fire is. They only assume that this is a mixture based on oil, and Byzantium purchased oil from the territory of modern Georgia and the Krasnodar region - then the country of Zikhia was located there. Now there is no oil to be extracted there, and even if there was some, crude oil burns poorly, and nothing is known about Byzantine methods of oil processing. If Byzantium really used a siphonophore, it probably managed to win battles on the water without difficulty.

Siphonophore

This last type of medieval throwing weapon, strictly speaking, cannot be called “non-fire,” although it does not use gunpowder. He shoots with fire—Greek fire. In essence, this is a Byzantine naval flamethrower. It is also simply called a siphon.

Many people mistakenly believe that Greek fire was thrown exclusively from catapults. If this were so, he would never have provided the Byzantine fleet with such decisive superiority over all rivals. After all, a Mediterranean war galley is a small, fast vessel and very inconvenient for aiming. And even more so - a Varangian or Slavic boat.

They say that a certain Callinicus from Heliopolis invented the siphonophore in the 7th century AD.

This device is a fairly simple sprinkler pump. It is not necessary to aim accurately with the burning mixture - it is enough to hit the target, and all the “excess” will still fall on the sea waves and quickly burn out without causing harm (this is why Greek fire was rarely used on land - there is a high risk of starting a fire where it is not needed). The spray easily covers both a large ship and a boat.

As for me, this is a weapon from the realm of fantasy. Anyone familiar with the design of a flamethrower will certainly agree with me.

In addition, what Greek fire is is not known exactly, but it is clear that it is some kind of petroleum-based mixture. Oil was bought by the Byzantines in Zikhia, a country located in the territory of present-day Georgia and the south of the Krasnodar Territory. In all likelihood, those sources have long been depleted, in any case, there is no visible oil there today. And crude oil generally burns very poorly, and for some reason they were silent about distillation devices in those days.

Rams, siege towers and assault ladders

Assault ladder –

the first siege weapon in history. The most ancient images of assault ladders have come down to us in drawings and bas-reliefs of Assyria and Egypt.

The assault ladder is an ordinary wooden ladder used to climb the walls to engage in battle inside the fortress. The length of the stairs was carefully calculated: a ladder that was too long was easy to push away, a ladder that was too short was simply impossible to climb.

An assault using ladders was only possible with a large numerical superiority - the attackers suffered heavy losses. Only one person at a time could climb the stairs, and those who climbed were met by defenders on the walls. Stairs were pushed away with spears or cut down, people fell from great heights, were injured and died.

Ram –

an ancient siege weapon known to the Assyrians. The simplest ram is a heavy log used to hit doors or gates. Over time, the ram was improved; a metal (iron or bronze) tip and belt loops were added to the log.

To increase the destructive power, the size and weight of the log increased. Human strength was no longer enough to operate such a ram, so a triangular frame was invented.

The log was hung from the crossbar on ropes or chains, and the frame was placed on wheels. The destructive power of such a ram increased significantly.

The defenders of the fortresses rained down on the assault team not only stones and arrows, but also boiling oil, resin or simple boiling water. Oil and resin were easy to set on fire, and the rams often burned down along with those who served them. To protect the assault command, a roof

.

A wooden or wicker roof could easily catch fire; to prevent this, it was covered with raw skins

and doused with water. In this form, the ram became a massive, protected and formidable weapon, almost irreplaceable when storming a gate.

Siege Tower –

tower on wheels, created before our era. The most active use of siege towers occurred in the Middle Ages.

The siege tower is a wooden tower with a quadrangular base, placed on wheels and lined with raw hides. A swing bridge was fixed at the top of the tower

, and the assault team hid inside, reliably protected from arrows and stones. The towers were driven by draft animals or pushed by hand. The height of the tower was equal to the walls or was slightly higher, so that from the upper platform archers could fire at the defenders of the fortress.

When the siege tower was brought to a sufficient distance, the bridge was thrown onto the wall

. The assault team quickly reached the walls, and then inside the fortress. If the attackers managed to capture and hold a piece of the wall, a tower, or especially a gate, the fortress was doomed.

For all their advantages, siege towers were rarely useful. The main difficulty was their transportation: bulky, clumsy structures were assembled at the site of the siege, this required timber and time. And it was only possible to transport the tower under the walls if the soil was hard and fairly level

.

In mud or swampy areas, the towers simply got stuck and were too heavy to drag along an inclined slope. If the fortress stood on a hill, it was not possible

.