Much has been written about the Hussite wars, but not about the weapons used in those days. They only say that the Czechs fought with the Germans using only flails and combat flails, which in the mass consciousness became a kind of symbolism of the Hussite wars. However, this is true to a certain extent: the role of impact-crushing weapons in the 14th-15th centuries was indeed very great. This is what we will talk about.

There are many myths on the Internet related to the weight and size parameters of various flails. They write that the mighty knights fought with five-kilogram flails so that fragments of enemy armor scattered several meters around. To a certain extent, this is a misconception: for the working part of a “classic” combat flail, a mass of 400 grams is almost the limit. But what is a “combat flail”? Is it appropriate to classify into one category a large two-handed kettenmorgenstern, a Hussite “kropach” and what is a flail in the narrow sense of the term?

Jan Zizka with a large infantry kettenmorgenstern. This most famous image of the commander is often mistaken for a lifetime portrait, although it is two centuries younger than the Hussite wars

Since the names have already been mentioned, we will also give a transcript. “Ketten” in German is a chain, therefore, Kettenmorgenstern is a chain morgenstern (a morgenstern was simply a name given to a spiked mace, the striking part of which is mounted not on a chain, but directly on the shaft). Translated from German, Morgenstern means “morning star” (the shape actually resembles a star, plus this phrase is an outdated form of the greeting “Good morning!”). By comparison, the Flemings called their halberds "godendak" ("good day"). A great way to warmly greet the enemy!

Among the Czechs, such humor acquired a slightly heretical connotation, which is not surprising for the era of religious wars. The name “kropach” spread because some combat flails were shaped very much like a church sprinkler - despite the fact that the impact caused splashes of blood to fly in all directions. Most likely, this funny name was born among the Taborites, but then it took root among Catholics: a similar comparison migrated into the languages of several European countries.

To avoid confusion: the working part of a flail is a “spindle” stick (that is, a nunchaku is, in fact, a flail). The blow of the flail and its derivatives most often has a spherical shape. The beater of the Kettenmorgenstern could also have not a spherical, but a pear-shaped shape; it could be a truncated cone and various kinds of biconical, pyramidal-prismatic figures.

The largest of them had a volume of about 700 cm³: they are present in catalog inventories, and surviving examples are exhibited in museums in Europe. There were even death machines with a hammer of 800 cm³ and a shaft like a halberd. And there were quite a few kettenmorgenschetrns with a working part of 400–500 cm³ (that is, up to half a liter).

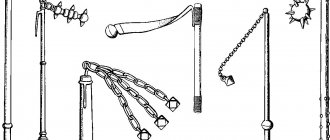

Various types of impact weapons from Hussite times

It is worth noting that this is actually the working maximum. In terms of the weight of the working part alone, it approaches 4 kg, and if you take into account the chain and handle (inevitably strong, massive, carved from dense wood like elm, and even in a couple of places bound with iron, and sometimes with additional points), then the entire unit is exactly will pull six kilos. There have never been such heavy halberds in the world, and even the largest two-handed swords among combat swords do not reach this weight by about a kilogram, usually one and a half. The reservation about combat ones is important: a ceremonial or training two-handed weapon was a quarter, even a third more massive than its “colleagues” who actually fought. It may very well be that the above-mentioned massacres were used not so much in battle, but before it to train fighters. For the Middle Ages, this method was quite typical.

One way or another, the large kropach is the most massive variant of a polearm. Moreover, there are three balls on one weapon: not the maximum size, but 200 + 50 cm³ each. In some varieties of flails, the spiked ball was attached to the shaft with a very short, literally single-link piece of chain. In other variants, a completely flail “drummer” - cylindrical, wooden, forged at the end and along, in which groups of spikes are fixed - is mounted on a very long chain, about thirty centimeters. It is impossible to distinguish these structures by the length of the shaft: in most cases it is intended for a two-handed grip, and its dimensions, regardless of the shape of the striker, usually range from 110–180 cm.

Double and triple kettenmorgenstern (modern replicas)

History of origin

It is impossible to clearly track the time of the appearance of the flail. Herodotus also pointed out in his writings that in the 6th-4th centuries BC the Scythians (they lived in the south of Eastern Europe and Asia up to Mongolia) used whips as weapons in battle. Thus, before the flail appeared, it remained to attach a bone or stone weight to the end of the whip.

It has been established for certain by historians and archaeologists that the Eastern European variants of the flail originated from its various Khazar variants. Among these nomadic tribes who lived in the lower and middle reaches of the Volga, the use of combat flails was noted in the 4th-9th centuries AD.

This weapon was very suitable for the light cavalry of the nomads and could well be used along with the saber as a first strike weapon.

Since nomads constantly attacked neighboring states, it is not surprising that the flail spread in the 10th century in Ancient Rus', which was constantly subject to raids from the south.

Residents of Rus' appreciated this first strike weapon, and soon it began to be used as an auxiliary weapon for horsemen and foot warriors. Of course, the technique of working with a flail was changed in accordance with the characteristics of the fighting of our ancient ancestors.

The appearance of these bladed weapons in Central Europe is associated not only with the raids of nomads, although there were plenty of them, but also with the migration of peoples during the Middle Ages in general. Here we should recall the resettlement of the Volga Bulgars to the territory of modern Bulgaria, and the Hungarians from the Urals to the territory of modern Hungary.

These peoples were familiar with the technique of fighting with flails, and in their new place of residence they remained faithful to their previous traditions. Given the short European distances, these weapons quickly spread, first across neighboring countries, and then throughout Europe.

Here it should be remembered that the European armies of the 10th-15th centuries had armored and invulnerable knights as their main striking force.

It is clear that neither a bone nor a stone flail can cause much damage even to a knight’s helmet, so the striking part became metal.

The pinnacle of the evolution of this weapon in Europe was the appearance of the morning star (morning star), in which the striking part was a small ball with spikes.

One should not think that such weapons were common only in Europe - since the idea of attaching a striking part to a handle on a belt or chain is very simple, various versions of these weapons appeared almost everywhere where people lived.

It is worth noting the difference between weapons created from tools of production, such as a flail. Combat flails (nunchucks), unlike flails, had a shortened flexible coupling and a longer handle and striking part, which radically changed the fighting technique.

Tactical and technical characteristics of the flail

In the usual combat version, the total length of the weapon was 45-55 cm. The flail consisted of a striking part - a beater, which could be of different designs. The stick or handle was usually made of wood. For noble warriors, it was customary to decorate the handle with various metal parts, giving the weapon a special value. The handle could be covered with leather for a comfortable grip. At the end there was a leather loop through which the hand was fixed to the wrist.

Iron beater

In medieval Europe, where there were better technical conditions for the manufacture of metal bladed weapons, various models of flails appeared. The knights preferred to have a morning star, which had a metal beater with steel spikes. A blow to steel armor with such an object could be fatal to the enemy. The spikes easily pierced armor and helmets. Among the warriors who owned these weapons, they adhered to the following principle - one blow - one death.

The German morning star or flail, which began to appear in the arsenal of private feudal armies, was made quite primitively and crudely. Only with the beginning of the Crusades, when an unspoken competition arose between noble knights in the quality of combat equipment, more noble examples of these weapons appeared. The handle was initially missing. The chain with the weight was simply put on a wooden stick if necessary. In some versions, at the end of the chain there was a special hook - a bracket on which some kind of load could be fixed as a beater.

The noble cavalry, which preferred to show off in front of each other, introduced its own innovations to combat equipment. Weapons become more sophisticated. Particular emphasis is placed on the appearance of the weapon. The flail handles take on a more convenient shape for gripping, with a square or oval cross-section. For a warrior in the thick of hand-to-hand combat, it was important not to let go of the weapon at a crucial moment. For more effective use of edged weapons in combat, the weight standards of the striking part begin to be taken into account during manufacturing.

For example: A lead beater the size of a walnut and weighing 200-300 g when hit during a backswing produced a force of 16 kg per cm2. One can only imagine what the warrior felt when receiving such a blow.

It is not advisable to make a larger weight. More weight entails more effort. The inertia of a heavy beat created during a swing can only harm the warrior himself. In addition, a brush with a large weight was inconvenient in battle. There might not have been time for a full swing. The greatest effect was produced by short and sharp wrist blows.

Flail Mastery

Manufacturing materials and device

The flail is a percussion-crushing weapon consisting of a striking part, suspended on a flexible belt from the handle or without it.

A variety of materials were used for manufacturing; this is an extremely affordable weapon in terms of material; it is not necessary to use high-quality steel for the striking part; it is quite possible to use improvised stones or bone.

Only morningsterns have some variety in appearance - this weapon was often used as an additional weapon by knightly cavalry and therefore differed for the better from the weapons of commoners.

Since the device of the flail is very simple, we will reduce it to one list:

- lanyard or extinguisher - an additional device for comfortable grip into which the hand is threaded. The material used was animal skin;

- handle (handle) - a device for gripping, the most common version was made for gripping with one hand, but there were also those that allowed you to work with both one and two hands. The most popular material was wood, but there were also metal ones. Often, for ease of carrying, flails were made without a handle; in this case, it was replaced by a damper - a loop through which the hand was threaded;

- connecting link (belt) - a flexible part designed to connect the handle with the striking part. There are not many options for materials: rope, leather belt, metal chain;

- flail (weight) - the beating part of the weapon, made of bone, stone, various metals, and occasionally wood was used. Often the load had convex spikes or ribs to increase the traumatic effect. In addition, the morning stars used by nobles were often decorated with family coats of arms and engraving.

Historical combat experience

In the history of wars, the flail is rarely mentioned as the main weapon. The popularization of this bladed weapon is more connected with the modern interpretation of the historical events of medieval Europe. A horseman clad in knightly armor, waving a spiked metal weight dangling from a chain, must have looked quite spectacular and impressive. In reality, such a sight was rare. It was common to see such weapons in the hands of militias and commoners.

In Russian history, mass combat use of the flail occurred during the struggle of the northwestern principalities with the Teutonic Order. The Russian militia, composed of commoners and poor nobles, were armed with spears, pikes and flails. Such weapons were used against heavily armed Teutonic knights. A blow with a flail on the helmet or on the back had a stunning effect on the riders. Suffice it to recall the victory of the Russian army on Lake Peipsi, where Russian regiments, together with the Novgorod militia, defeated the Teutonic knights.

Battle Flail

In direct clashes with German knights, Russian horsemen usually used axes and spears. In Europe, the flail was actively used on the battlefield during the European Crusades against the Czech Republic. The Hussite wars were the first domestic wars in which the main striking force was not regular troops, but the people's militia. The Hussite troops were armed with a wide variety of weapons, including flails. The weapon looked like a heavy steel flail, capable of not only knocking a rider out of the saddle, but also crushing the first ranks of the advancing enemy.

After the first military clashes with the militia, the Czech nobility began to use the flail as an auxiliary weapon. The impact part began to be made heavier and equipped with additional spikes. For better flexibility, the chain links were reduced, making the weapon more convenient for combat use.

morning Star

The most legendary weapon of this type is the flail called the morning star. It was a device with a heavy core on a chain. The striking part was studded with long spikes. In parallel with this type of weapon, varieties of flails with three weights dangling from a chain appear. This approach is more related to the psychological effect. It is almost impossible to use such weapons in combat. The terrifying appearance did not correspond to the real combat power of such weapons.

Use in combat

The main factor in combat flails is the speed with which the blow is struck, therefore the striking technique used in battles implied a wrist blow with a short swing or without one at all.

The blow itself had to hit the enemy's head or body; it was even possible to hit his unprotected back (due to the presence of a rather long chain). This was due to the fact that the flail is a weapon of the first strike, and it was almost impossible to defend with it.

Even with a metal flail handle, it was almost impossible to repel a blow (no matter what weapon) due to the unpredictable behavior of this handle and the load.

The films beautifully show that with a flail or just a chain you can take away a sword or pike from an enemy. In practice, everything is not so clear. You can get wounded by your own flail.

In the nomadic armies, this weapon was successfully used in cavalry.

Light cavalrymen successfully used the flail as an additional weapon in the lands of Ancient Rus'. This is due to the difference in the history of Europe and the eastern part of Ancient Rus', to which the era of chivalry did not reach.

In Europe, in the Middle Ages, heavily armed knights on the battlefield, who relied on the force of the blow, and not on its speed, used the flail extremely rarely. Heavy ammunition did not allow for a quick wrist strike, and the weapon itself was considered a weapon of commoners.

The use of this weapon by knights was recorded only in cases when in battle he was deprived of his more familiar weapons - a sword, spear, battle axe, and this applies to the morning star, and not to the flail.

On the other hand, having a saber and a flail technique proven in battle, a lightly armed warrior penetrated the defense of a heavily armed shield-bearer. The low cost of production made it possible to easily and in a short time arm an army of rebel peasants or conscripted militias, since their weapons were non-combatant.

As one of the main types of weapons, the flail was used in European wars in only one army - and this was the army of the rebel Czechs under the leadership of first Jan Hus and then Jan Žižka.

It should be remembered what the Hussite camp was like - these were war carts placed in a circle, behind which the army was hiding.

When the enemy tried to break into the camp, each of the defenders had time for one blow. The Czech peasants with these weapons (which by that time had become similar to a morning star) were able to successfully go on the attack, literally mowing down a number of enemy soldiers at the first blow.

With the development of technology, edged weapons were increasingly replaced by firearms. This trend did not bypass flails, although their last use in battle was recorded during the First World War. But this was the improvisation of individual soldiers, and not generally accepted army practice.

Historical combat experience

In the history of wars, the flail is rarely mentioned as the main weapon. The popularization of this bladed weapon is more connected with the modern interpretation of the historical events of medieval Europe. A horseman clad in knightly armor, waving a spiked metal weight dangling from a chain, must have looked quite spectacular and impressive. In reality, such a sight was rare. It was common to see such weapons in the hands of militias and commoners.

In Russian history, mass combat use of the flail occurred during the struggle of the northwestern principalities with the Teutonic Order. The Russian militia, composed of commoners and poor nobles, were armed with spears, pikes and flails. Such weapons were used against heavily armed Teutonic knights. A blow with a flail on the helmet or on the back had a stunning effect on the riders. Suffice it to recall the victory of the Russian army on Lake Peipsi, where Russian regiments, together with the Novgorod militia, defeated the Teutonic knights.

In direct clashes with German knights, Russian horsemen usually used axes and spears. In Europe, the flail was actively used on the battlefield during the European Crusades against the Czech Republic. The Hussite wars were the first domestic wars in which the main striking force was not regular troops, but the people's militia. The Hussite troops were armed with a wide variety of weapons, including flails. The weapon looked like a heavy steel flail, capable of not only knocking a rider out of the saddle, but also crushing the first ranks of the advancing enemy.

How does the law relate to flails?

In the last century, brushes began to appear in a simplified version, which did not have a handle and represented a weight on a chain, or a piece of watering hose with a large nut at the end. Such options became especially widely used in criminal disputes that began after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Nowadays, the Federal Law “On Weapons” classifies the flail as a bladed weapon.

Its production, storage and use is illegal. But only forensic examination can determine the characteristics of a weapon, therefore, morningstars certified as souvenir weapons are not such.

But if the examination considers that the presented flail is a bladed weapon, its manufacture and storage will be punishable under Art. 223 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

Where did such bladed weapons come from?

Judging by its shape, the flail is clearly intended for horse fighting. This is due to the lightness of the weapon and its great mobility. A horseman who skillfully handled such weapons and mastered the techniques of equestrian combat could freely deliver a sudden, devastating blow to the enemy. The force of the backhand strike was so strong that the opponent could easily be knocked out of the saddle. If the blow fell casually, then the rider who remained in the saddle would be stunned for some time. Only a shield could save him from a crushing blow from a metal weight. The steel armor of warriors rarely provided reliable protection from a deafening blow from a heavy weight during a combat clash. The large kinetic energy during the swing, multiplied by the weight of the weapon, provided enormous force to the blow. The only argument that could be opposed to such cold weapons was striking first.

It should be noted that during the battle, the flail was rarely used. Rather, it was an auxiliary weapon that warriors used when it was impossible to use the main types of weapons. If a spear or pike was lost, or a sword was lost, such a bladed weapon as a flail became the last powerful argument for a warrior. However, many warriors from among the nobility neglected the combat capabilities of such weapons, considering them to be the weapons of commoners.

The first information about the combat use of the flail appeared in Europe at the beginning of the 11th century. Over time, it became clear that such a device, used as a bladed weapon, is quite common in the world. Weights on a chain were used by knights of medieval England, Germany and Italy during the Crusades. Muslims also had similar weapons. The heavily armed horsemen of Salah ad-Din's army used flails in confrontation with the knights - the crusaders. In ancient Japanese drawings and frescoes you can see a flail on the equipment of samurai.

In the form in which we present this weapon, it appeared much later. Originally it was a battle flail, very reminiscent of a device for threshing grain. Later, attempts were made to modernize this type of bladed weapon, making it more respectable and representative. In Rus', a similar type of weapon was used during the campaigns of the ancient Russian princes against Constantinople and in battles with the Polovtsians and Pechenegs. Old Russian warriors were equipped with proven types of these weapons and mastered special combat techniques.

Kisten is a name with Slavic roots. The meaning of this word can be interpreted differently, but the essence does not change. The weapon was put on the hand and was activated by rotating the hand. Considering the fact that the Slavs had to fight for a long time against nomadic tribes of Turkic origin, an analogy can be drawn with the Turkic name. “Kistan” translated from the Turkic language means “stick”.

The popularity of the weapon is explained by its simple design and low cost. The prototype of the combat flail is a threshing stick, which was often used to arm the militia. Having quickly identified the fairly high effectiveness of the device in battle, they changed its shape. The stick was shortened, and a beater made from animal bones was attached to a chain. For wealthy warriors, the flail receives a metal beater. From a two-handed type, the weapon turns into a one-handed one, lighter and more flexible. Its impact-crushing effect is enhanced. In Rus', the name of the weapon was finally established, while in Europe such edged weapons are called in the German manner - morningstern.

What traces of the flail remain in literature and history?

The successes of the use of flails by the Hussites and German peasants during the German wars were reflected in Talhoffer’s treatise “Old Weapons and the Art of Fighting,” published in 1459.

It, along with the morning star that came into use, recommended the use of its improved version with three small balls instead of one.

Another mention can be found in the treatise of Sigismund Herberstein, which described the morals and customs of medieval Muscovy.

Flails were also mentioned as one of the types of cavalry weapons, and they were required for protection even when Grand Duke Vasily III went hunting.

It stands o - a tactical knife, the creator of which is A. M. Kisten, a master of knife fighting of our time. But this is no longer relevant to our topic.

The use of combat flails

In military history, flails were not often mentioned as the main weapon in battles. Their wide dissemination was due to the modern interpretation of history in medieval Europe. Especially in films, for the sake of entertainment, horsemen were depicted clad in knightly armor and waving spiked metal weights dangling from chains. In reality, such a picture was very rare.

Russian history knows about the massive combat use of flails. This was at a time when the northwestern principalities were opposed to the Teutonic Order. Russian militias, which included commoners and poor nobles, preferred to have spears, pikes and flails in their weapons. In direct clashes with German knights, Russian horsemen, as a rule, used spears and axes. Europeans actively used flails during the Crusades against the Hussites. It was the Hussites who were armed with everything they could get their hands on, including flails. In their hands, they looked like heavy steel flails, capable of not only knocking riders out of their saddles, but also crushing the first ranks of advancing enemies.

As soon as the first military clashes with the militia took place, the Czech nobility had to use flails as an auxiliary weapon. The impact parts were made heavier and equipped with additional spikes, and to improve flexibility, chain links began to be reduced. Everything was done to make the flails convenient for combat use.

The most legendary flail was a device called the “morning star”. It looked like a weapon with a large core on a chain that was all covered in long spikes. There were other types of flails with three beaters on chains, but they were made mainly for psychological effect. It was not possible to use such weapons in real combat. Such samples were mainly made to intimidate the enemy.

The combat use of flails cannot be compared with battle axes, spears and swords. However, as a cultural value they have earned their place in the historical heritage. It was not without reason that gunsmiths gave their creations special shapes. Whether the flails would have been useful in battle or not is unknown, but they would definitely have adorned the equipment of warriors with their presence.

Two-handed flail

Two-handed flail (aka threshing

) directly comes from peasant; most often this is an agricultural tool, at most with a weight weighted or studded with nails.

Its handle is one and a half to two meters long, and the suspension is very short, literally a few links. It is not intended for serious military equipment; the ears usually do not dodge. And in battle, all hope is that you will have time to strike first, because a fighter with a two-handed flail is absolutely unprotected. There is nothing to hold the shield with, and you won’t be able to parry either. In short, this is truly a suicide weapon; however, it served the Hussites and Flemings faithfully due to their numerical advantage and the fact that the knights stubbornly continued to underestimate “these men with flails.”

There were two-handed flails with several loads, but in battle the extra ones were usually unhooked - very inconvenient; one such flail became a scepter in ancient Egypt.