British Naval Forces (England)

Great Britain, a country that has written its name in history thanks to its Royal Navy. In order to explain their structure, history and general characteristics, it is better to divide this article into paragraphs.

The official date of the formation of the Royal Navy is considered to be 1717, the year of the formation of the parliamentary kingdom (after the British Civil War of 1642-1651), the rule that Great Britain enjoys to this day. However, the first naval forces were created at the end of the ninth century, between 871-899. King Alfred of Wessex was the first to use a fleet to defend the kingdom. Until the thirteenth century, warships were used to protect coastal areas. The first naval battle of the British fleet took place in the naval battle of Sluise in 1340. In the sixteenth century, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the navy became the main branch of Britain's military.

Despite the fact that Great Britain is a maritime country, the English fleet could not achieve the status of the strongest in the world for a long time. Strong flotillas of France, Spain, Portugal, and the Ottoman Empire hampered the development of the Royal Navy. This continued until the eighteenth century. The Civil War created a new system in the country, after which Great Britain began to develop at a rapid pace in all directions. The name "Royal Navy" was first used just after the Civil War, during the reign of King Charles III.

Subsequently, while searching for new trade routes, humanity learned about the existence of America. An active struggle for colonies began among all the powers of that time. Thanks to the timely development of the navy, Great Britain was able to conduct a successful colonial campaign. As a result, Britain's opponents, represented by Spain and France, created a coalition against it. The decisive battle took place on October 21, 1805 at the naval battle "Trafalgar", where the English Fleet led by Admiral Nelsan inflicted a shameful defeat on the coalition forces. The Royal Navy had 21 warships, while the coalition had 39 ships. The peculiarity of this battle is that after it, Great Britain became the strongest naval power in the world and destroyed Napoleon's idea of capturing Great Britain. Moreover, the naval battle of Trafalgar is considered one of the three great naval battles in history. After this, nothing could stop Great Britain in its colonial campaign and gaining the status of “The Empire on which the sun never sets.” This state of affairs lasted until the First World War.

Strengths and plans of the parties

Deployed for operations against Malaya (Operation E), Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake's 2nd Fleet was called the "Reconnaissance Force" and consisted only of cruisers and destroyers. The 4th and 7th cruiser divisions and the entire 3rd destroyer squadron (11th, 12th, 19th and 20th divisions) - 5 heavy and 2 light cruisers, as well as 14 destroyers united in the Southern Expeditionary Force. The overall command of them and the entire landing operation was exercised by Rear Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo.

Vice Admiral Kondo Nobutake history.navy.mil

The landing force consisted of three convoys with the advance detachment of the 25th Army of Lieutenant General Yamashita Tomoyuki - the future “Tiger of Malaya”:

- 11 transports, accompanied by 4 destroyers (“Asagiri”, “Amagiri”, “Yugiri” and “Sagiri”, the latter housed the headquarters of the entire landing) - in Singora in Thailand;

- 5 transports, accompanied by 3 destroyers (Sinonome, Shirakumo and Murakumo) - in Patani in Thailand, 65 miles south of Singora;

- 3 transports, accompanied by the light cruiser "Sendai" and 4 destroyers ("Isonami", "Uranami", "Sikinami" and "Ayanami") - to Kota Bharu in northern Malaya.

In addition, 8 transports sailed without destroyer cover and landed troops at separate points on the coast of the Gulf of Thailand north of the landing site of the main forces: at the Kra Isthmus (one transport), in Prachuap (one transport), in Chumphon (two transports), near Bandon ( one transport) and near Nakhon (three transports).

In total, 28 transports, a light cruiser, seaplane transport and 11 destroyers took part in the landing. To protect the formation of heavy cruisers, which provided close cover for the operation, Ozawa retained a light cruiser and three destroyers.

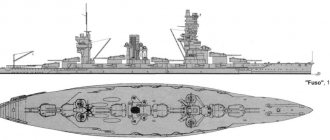

Battlecruiser "Congo". Type and reservation scheme as of the beginning of the 30s, after the first modernization of the Breeze, 1995, No. 4

For combat stability, Kondo also received half of the 3rd battleship division - the old battlecruisers Kongo and Haruna, accompanied by a dozen more destroyers. These ships, along with the heavy cruisers Atago (Kondo's flagship) and Takao, remained under his personal command. Japanese battlecruisers (contemporaries of the Repulse) had slightly more powerful artillery and armor, but slightly lower speed.

They could not compete with the newest "Prince of Wales", in addition, Kondo believed that the second British battleship was the same type "King George V". Therefore, he did not hope for victory in a linear battle and kept his main forces off the eastern coast of Indochina, without leaving under the fighter “umbrella”. At the same time, Ozawa’s heavy cruisers, which provided cover for the landing force, were of little importance in a daytime battle and were unlikely to be able to withstand even one Rivenge. Their only chance was a torpedo attack in the dark.

Thus Admiral Phillips had a decisive superiority in line forces. At the same time, he could allocate the Revenge directly to attack convoys, which were still inferior in speed to the old super-dreadnought. His only problem was the acute shortage of destroyers - but Ozawa also lacked them, who needed destroyers to escort transports.

Rear Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo in Saigon, November 16, 1941 Wikimedia Commons, PD-JAPAN-oldphoto

History of the English Navy

England's first warships were rowing ships. Over time, they were replaced by sailing ships, which Great Britain used for a long time. With the advent of steam engine technology, the Admiralty turned their attention to this and began building steam-powered warships in the early nineteenth century. The first steam-powered warship was the Comet. Over time, para-ship frigates switched from a wheeled propulsion system to a screw-driven system. To do this, they conducted a power test, where propeller ships showed their superiority. The first large propeller-driven combat vessel was the frigate Agamemnus, which had 91 naval guns on board. The first battleship "Varior" appeared in 1860. In the 1870s, with the advent of torpedoes and sea mines, the first torpedo boats and destroyers appeared. Thanks to its developed shipbuilding industry, unlike other countries, Great Britain did not have any special problems with the construction of ships and their maintenance. However, following the economic growth of other countries, the Admiralty introduced the Dual Power Standard, as a result of which the Royal Navy was supposed to be stronger than any two navies in the world combined. This led to a slowdown in the development of the power of the British Navy. The 1890s ushered in the era of the battleship, in which Great Britain had a significant advantage over other powers thanks to its battleships with 12-inch naval guns. However, the advent of submarines at the beginning of the twentieth century dispelled any thoughts about the superiority of battleships. The first submarine, Holland I, was built and launched in 1901. The length of this type of submarine "7" was 19.3 meters.

Royal Navy during the First World War

During the First World War, the Royal Navy was still the most powerful in the world. Thanks to successful military operations, he repeatedly won victories in such battles as in the Heligoland Bight, at Coronel, Falklensky, at the Dogger Bank and, of course, in Jutland. In the last of these battles, Great Britain ended all German hopes of success at sea. In 1914, the Royal Navy destroyed the German East Asia Flotilla. Moreover, the navy was the main protector of the merchant ships of its allies.

Another important aspect of the First World War was the use of aviation and the construction of seaplane carriers. The first seaplane carrier Argus was built in 1918.

Royal Navy during the Second World War

After the First World War, the time came for Wilson to preach about world peace, after which the “Washington” Agreement and the “London” Agreements were signed, limiting countries to the presence of a fleet. In this regard, Great Britain encountered real problems, as a result of which it had to reduce the size of its fleet.

Despite restrictive agreements, Great Britain entered the Second World War as one of the leaders in naval performance. The Royal Navy played a huge role in stopping Nazi Germany, preventing the latter from capturing the British island. Moreover, the British naval forces supplied provisions to Malta, North Africa, Italy (after the death of Mussolini); provided artillery support and blocked strategically important places.

The Royal Navy suffered real losses during the Second World War. The successful actions of the German fleet, in particular the submarines, sank the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, about 10 cruisers, 20 destroyers, 25 frigates and many other minor warships.

Royal Navy of England during the Cold War

After serious losses in World War II, the Royal Navy lost its status as a maritime power. The security of the North Atlantic region has passed to the shoulders of the United States. However, the policies of Churchill, and then his followers, tried to restore the former power of warships. Thus, in the 1950s and 1960s, Great Britain began large-scale construction of warships: 2 Odessa-class aircraft carriers, 4 Centaur-class aircraft carriers, Lindair-class frigates and County-class destroyers. Subsequently, Great Britain overtook the naval military power of the Soviet Union. However, the Reforms of 1964 reduced the importance of the fleet, included the Admiralty in the Ministry of Defense and removed the fleet from the Suez Canal.

During the Cold War, the Royal Navy was involved in many regional crises: the Iran-Iraq War of 1962, the Tanganyika Crisis of 1964, the Indonesia Crisis of 1964-66, the Cod Wars of 1965 and the Foleyland War. The latter showed the power of the British Navy.

Why on the eve of World War II Britain was not ready to fight German submarines

In 1945, after the surrender of Germany, the Battle of the Atlantic, which became one of the largest battles in naval history, ended. During this confrontation, the Axis forces tried to challenge the naval dominance of Great Britain and its allies in the anti-Hitler coalition and establish a blockade of the British Isles, relying primarily on the capabilities of German submarines. By the end of the war, the British anti-submarine force was at the height of its power. They had at their disposal thousands of aircraft and ships capable of destroying submarines and protecting convoys from their attacks. This was facilitated by modern weapons and detection: anti-submarine homing torpedoes, depth charges with improved explosives - torpex, Hedgehog and Squid rocket launchers, as well as improved sonars and radars.

However, at the beginning of the war, British anti-submarine defense (ASD) was in a rather pathetic state. Despite the terrible experience of submarine warfare in the First World War, Great Britain managed not to prepare for new battles with submarines. At one time, the Kaiser's submariners extremely deftly dealt heavy blows to the shipping of the Entente and neutral countries. From 1914 to 1918, they sent 4,837 ships to the bottom with a total tonnage of over 11 million gross register tons. But, as it turned out, these losses taught the British government and its admiralty little. Being confident that this would not happen again, the British in the interwar period did not bother to properly improve their anti-aircraft defense systems. "Profile" analyzed the reasons for the failures of British anti-submarine forces in the early years of World War II.

Down with the submarines!

After the end of the war, the Entente allies tried to consolidate peace through treaties. Talk about disarmament began again. They were brought to a practical level in the sphere of naval weapons - the most costly for such maritime powers as Great Britain, the USA and Japan. Participants in the Washington Conference (1921–1922) agreed to significantly reduce their naval forces. In addition, London advocated for the removal of submarines from service and a ban on their construction, but did not find support. He only managed to achieve the establishment of a limit on the total tonnage of submarines for each country. For example, in the English and American fleets it amounted to 90,000 tons, for the other participating countries it was 45,000 tons each.

The British did not give up attempts to ban submarines. But they also met with failure at the conferences in Geneva and London. Nevertheless, at the London Conference of 1930, strict rules for the actions of submarines against merchant ships were developed. According to Article 22 of the London Treaty, submarines could only act in accordance with international law. They were forbidden to sink merchant ships without stopping and inspecting them, without ensuring the safety of their crews and passengers (lifeboats were not considered a safe place). Exceptions were made only for convoys or if a merchant ship refused to stop, thereby impeding inspection.

After the adoption of these rules, Great Britain calmed down, deciding that the horrors of submarine warfare were a thing of the past. The British faith in the power of the treaty was so great that in 1935 London and Berlin entered into an agreement that allowed Hitler to officially include submarines in the fleet, the total tonnage of which, however, was strictly limited to 45% of the tonnage of the British submarine. Thus, Great Britain itself allowed Germany to violate the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which in principle prohibited the Germans from having any submarines.

“Mistress of the Seas” Britain was surprisingly ill-prepared for an underwater confrontation with Germany. The situation improved only at the turn of 1941–1942. In the photo: the engine room of a British submarine

Print Collector / Vostock photo

Lesson unlearned

Believing that there was no need to fear a new submarine war, and at the same time saving the military budget that was dwindling in the conditions of the global crisis and the general weakening of the empire, Great Britain was not too eager to develop anti-aircraft defense. And this was fully consistent with the concept of disarmament, which entailed a reduction in funds allocated for the development of the fleet. However, this cannot be said that the British did nothing at all. But what was done was clearly not enough to protect sea communications from the underwater threat in case of war. Let's take a closer look at the anti-submarine weapons and weapons that Great Britain possessed at the beginning of World War II.

Anti-submarine ships

During World War I, the British Navy had hundreds of destroyers, but by the mid-1920s little remained of most of them. In 1927, the Admiralty began building modern ships, receiving 109 new destroyers by 1939. But some of them were transferred to Canada or converted into mines, which reduced the total number of destroyers to 91 units. The British Navy also had about 60 obsolete ships of this class. As a result, by the beginning of the war it consisted of a little more than one and a half hundred destroyers scattered throughout the globe. Most of them were not intended to protect shipping and escort convoys, since modern ships were needed to protect battleships and aircraft carriers, reconnaissance and other tasks.

The situation was somewhat brightened up by sloops - this is how specialized escort vessels were classified. The British had about 30 ships of this class. Together with some of the old destroyers, the sloops were supposed to form the basis of the escort forces of ocean convoys. Thus, the British fleet could allocate no more than fifty warships for this task. The protection of coastal shipping became the task of mobilized trawlers, equipped with cannons and depth charges. The Admiralty understood that in the event of war these forces would not be enough to ensure the safety of British shipping. At the same time, the country was critically dependent on imports by sea. Therefore, in 1939, more than 70 ships were built at the shipyards: Hunt-class escort destroyers and Flower-class corvettes. The former were intended to escort convoys on the ocean, the latter to protect coastal shipping. But by the beginning of the war, the construction of both was still far from complete.

In other words, the British Navy had only a minimum of anti-submarine ships to protect shipping from submarine attacks. But maybe the Royal Air Force could help them?

British pilots on board an aircraft carrier

Print Collector / Vostock photo

Anti-submarine aircraft

During World War I, only one German submarine was destroyed from the air, however, British naval experts appreciated the prospects for creating anti-submarine aircraft. But in practice, little was done. As a result of the 1936 reforms, the Royal Air Force was divided into bomber, fighter and coastal commands. The latter's tasks included combating submarines. By September 1939, the coastal command had three hundred aircraft under its command. However, only three squadrons were equipped with modern aircraft: two squadrons of Short Sunderland flying boats and one squadron of Hudson bombers.

Despite the popular belief that the coastal command was capable of effectively performing anti-submarine defense functions, the reality turned out to be different. After the outbreak of the war, it turned out that the preparations were completely insufficient, and this is not surprising, given that the development of this area was at the bottom of the list of priority tasks of the Ministry of Aviation. Modern aircraft were in short supply and were not equipped with submarine detection capabilities or suitable weapons to attack them. Coastal Command pilots were ill-prepared for the mission. The situation with ship-based aviation was not the best either.

The Admiralty believed that carrier groups would become a formidable opponent for submarines. It was assumed that an aircraft carrier, accompanied by modern destroyers, was capable of controlling a vast area: its aircraft could detect and attack submarines or report them to the destroyers, guiding them to the target. However, of the six Royal Navy aircraft carriers in service, only one was modern, and the carrier-based aircraft consisted of only 175 aircraft: 150 old torpedo-bomber biplanes and 25 new dive bombers. The main emphasis in the training of its pilots was on attacks on large surface ships, and not on searching and destroying submarines.

Submarines

During the First World War, British submarines successfully hunted German submarines, so the Admiralty hoped to use them in anti-submarine patrols in the North Sea in the event of a new war. But, as in other cases, things here were not the best. In 1919, the British fleet had 122 submarines. During the interwar period, their number was reduced to 57, of which only 18 were in the metropolis. Like deck pilots, submariners were trained primarily for attacks on large ships. Therefore, they mastered a full bow salvo well (6-8 torpedoes in a fan), but they practically did not practice firing a smaller number of torpedoes. The Admiralty did not regard the enemy submarine as a large target and allowed only 2-4 torpedoes to be spent on it, while the techniques for firing a small number of torpedoes were very different and required separate training.

What to look for and how to drown?

The creation of the Asdik sonar in the UK was a real breakthrough in anti-aircraft defense. With its help, the ship was able to detect a submarine underwater for the first time. But servicing the device required the operators to have good training, which not everyone received before the war. The Admiralty managed to equip 185 ships with Asdics before the war, 100 of which were modern destroyers. The remainder came from sloops, trawlers and obsolete destroyers assigned to convoy duties. However, the capabilities of this miracle device were offset by the imperfection of depth charges.

The main anti-submarine weapon of the British was the “barrel” - a depth charge of a characteristic shape, rolled from guides at the stern of the ship. Since the First World War, it has “fatten”, increasing the charge from 140 to 230 kg of TNT, but this is where its evolution ended. The “barrel” could not quickly reach the required depth and explosion site when dropped from the stern of the ship. Despite the impressive amount of explosives, the “barrel” was not a panacea in the fight against submarines. Their hull was so strong that damage could only be caused by an explosion 3–6 m from the submarine. Since the boat evaded movement after each release of the “barrels,” it was very rare to achieve such a result. The British themselves were for a long time under the delusion that the submarine was destroyed by a bomb exploding 20 meters from it. Before the war, they also did not think of changing the body of the depth charge to speed up its descent, equipping it with a more powerful explosive and creating bomb launchers for it.

The situation was even worse with the armament of anti-submarine aircraft. Air bombs with a rotary fuse were created for them, with which they were supposed to attack submarines on the surface or during a dive. But this weapon was of little use, since it would only be possible to accurately hit the submarine with such a bomb only with incredible luck. Attempts to drop “barrels” from aircraft also did not produce results. Having no stabilizers or an aerodynamic shape, they flew along an unpredictable trajectory, and often broke apart when they hit the water. As a result, British pilots preferred to fly anti-submarine patrols with conventional bombs. Before the war, no one in Great Britain was involved in the creation of special aviation depth charges.

Something similar happened with means of detecting submarines on the surface. It was only in the mid-1930s that Great Britain began to actively develop radar equipment. Even before the start of the war, its scientists managed to create a device for aircraft and ships, but it was far from ideal. As a result, aircraft and shipborne radars were of little help in finding submarines - they lacked the power to find targets of this size. These devices required improvement, but before the war, the main efforts were devoted to creating a network of coastal radar stations needed to guide fighters to enemy bombers attacking targets on the islands.

The death of the aircraft carrier USS Coreys, sunk by a German submarine in 1939, came as a real shock to Britain. 518 sailors died along with the ship

Shutterstock/Fotodom

There was no happiness, but misfortune helped

To summarize, we can state: Great Britain was ill-prepared to protect its communications and shipping from submarine attacks. The great naval power believed that the nightmare of submarine warfare would not be repeated, and did not improve its anti-aircraft defense systems. London allowed Germany to have submarines prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles. Convinced of the impossibility of revenge, the British did not even pay attention to the publication of a book by the commander of the Reich submarine forces, Karl Doenitz, where he advocated tonnage warfare and proved the possibility of effective operations of boats in British waters in the face of opposition.

Thunder struck when, after the start of the war, German submariners clearly pointed out to the British their mistakes. Dozens of sunk merchant ships, the sinking of the aircraft carrier Coreys, the breakthrough of Gunter Prien's U-47 into the main British fleet base of Scapa Flow in 1939, and the successes of Doenitz's submarines in 1940–1941 were the fruits of these mistakes. However, paradoxically, Germany itself gave Great Britain time to correct them. For two years, the Reich simply did not have enough submarines to take advantage of the head start provided by the British to organize an underwater blockade. Having started the war with 50 combat submarines, the Germans lost them in battles and were able to reach the figure of fifty submarines only by the end of 1941. In addition, all this time the German torpedoes left much to be desired.

Nevertheless, in the first years of the war, Germany, even with a small number of combat-ready submarines, was able to inflict a number of painful blows on British shipping. Great Britain could only defend itself with the forces it had. Therefore, Churchill’s words that the Battle of the Atlantic truly began for Great Britain in 1941–1942 ring true. Until this time, she could only correct mistakes made before the start of the war. It is quite possible that the British could have avoided many losses if London had shown foresight and foresight, but they had to learn during the war.

The landing force goes to sea

On December 4, a huge Japanese convoy consisting of 28 transports, the light cruiser Sendai (flag of Rear Admiral Hashimoto), seaplane transport Kamikawa Maru, 10 destroyers, 6 minesweepers and 3 submarine hunters left the port of Sama on the occupied Chinese island of Hainan.

On December 6, the convoy went around Cape Kamao (the southernmost point of Indochina) and turned west. At 12:12, the reconnaissance Hudson detected the Australian Ramshaw at 7º51'N, 105º00'E. three ships heading 310º. At 12:46, Ramshaw reported that at 8º 00'N, 106º 08'E he saw 25 ships, accompanied by 6 cruisers and 10 destroyers, heading 270º degrees. Finally, at 18:35, at 8º00'N, 102º30'E, a cruiser and a transport were discovered, and the cruiser (in fact it was an air transport) opened fire on the Hudson.

On December 7 at 8:30, having reached the conditional point “C” in the Gulf of Thailand, the transport detachments fanned out, heading to the intended landing points. At this time, a British Catalina appeared above the convoy, but it was immediately attacked by an Aichi E13A float scout launched from the Kamikawa Maru catapult. The machine gun fire destroyed the radio station, and the Catalina crew was unable to transmit information to Singapore that had a chance to influence the outcome of the operation. A quarter of an hour later, the Catalina was shot down by an army fighter Nakajima Ki-27 from air cover of the convoy, and was considered missing for a long time. The weather turned bad that day, and Admiral Phillips was left without “eyes.”

On the evening of December 7, three squadrons each of the Mihoro and Genzan air corps took off to bomb Singapore, but the Genzan squadrons were caught in a storm and returned to base. At 23:45, the southern convoy approached the Malayan port of Kota Bharu - the cruiser Sendai and 4 destroyers opened fire on the landing site. There was still about an hour left before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Japanese float reconnaissance E13 A-2 from the seaplane carrier Kamikawa Maru airwar.ru

An hour later, the transports Awajisan-maru, Ayatosan-maru and Sakura-maru began unloading, using their own boats, as well as the minesweepers W-2, W-3 and the Ch-9 hunter. At 02:10, the ships were attacked by seven Hudsons from the 1st Australian Squadron, and the Awajisan-maru, which was the headquarters of the 5th Infantry Division of Major General Takumi Hiroshi, was damaged, towed to shore and subsequently abandoned; two other vehicles were also damaged.

It was not until 4 o'clock in the morning that three squadrons of Japanese bombers rained down their bombs on Singapore, its airfields and the civil harbour. The raid showed the disgusting organization of British air defense: although stationary radars detected the appearance of enemy aircraft in time, the anti-aircraft artillery was not prepared to fire. As Richards and Saunders carefully write, “repeated requests by telephone to open fire were often not answered. The air raid warning in the city was not announced until the air force command addressed the Governor of Singapore on this issue.” Only three Buffalo aircraft from the 453rd Australian Squadron, based at Sembawang airfield, were in combat readiness, but they were not given permission to take off. Even the order to open fire with anti-aircraft artillery was not carried out on time due to the terrible communications and poor performance of the Singapore VNOS service.

The combat effect of the raid was insignificant - most of the dead (61 people in total) were civilians, and three Blenheims were damaged at the Tenga airfield. At 4:13 the order finally came from the Admiralty in London: “Commence hostilities immediately.”

A successful raid by British bombers and the resistance of the Indian infantry brigade stationed in Kota Bharu could not prevent the landing. During the day, the brigade reported that the enemy had bypassed its flanks and it was forced to abandon its positions on the shore. The landing of the remaining landing forces on Thai territory did not meet any resistance.