Project 941 Akula nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine

Underwater displacement 48,000 tons. Length 172 m, width 23.3 m, draft 11 m. Full submerged speed 25 knots. The power of the nuclear power plant is 100 thousand liters. With. Armament - 20 RSM-52 missile launchers (200 warheads), 6 torpedo tubes. Crew 160 people (including 52 officers).

Main goals and tasks

The task of designing and building a nuclear submarine capable of diving to a kilometer depth and striking the enemy from there had good reasons, due to the serious combat advantages obtained in this case. Such a deep-sea submarine was completely invulnerable to all possible countermeasures existing at that time.

The pressure of even half a kilometer of water destroyed both torpedoes and depth charges, usually used for anti-submarine warfare. In addition, even simply detecting a submarine at such a depth was an almost impossible task: the aquatic environment at depths of over three to four hundred meters changes its acoustic properties so much that it was almost impossible to detect the submarine using hydroacoustic devices.

According to the plan of the command of the USSR Navy, the deep-sea nuclear submarine was supposed to be used in combat operations in ocean and sea areas against enemy submarines, surface ships and transport vessels. The ship could also carry out reconnaissance missions and transmit data about the enemy to other Soviet ships.

However, the costs of developing and building this submarine cruiser were comparable to the price of an American aircraft carrier, and the cost of a conventional submarine was 5-6 times higher. At world prices, this amount was estimated at approximately 17 billion dollars, which was a huge figure for the USSR at that time. This is where the boat of the “Fin” project got the informal name “Goldfish”.

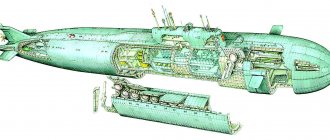

Diagram of the nuclear submarine "Komsomolets"

Project 667BDR Kalmar nuclear submarine with ballistic missiles.

Underwater displacement 16,000 tons. Length 155 m, width 11.7 m, draft 8.7 m. Full submerged speed 24 knots. The power of the nuclear power plant is 40 thousand liters. With. Armament - 16 RSM-50 missile launchers (48 warheads), 4 torpedo tubes. Crew 130 people (including 40 officers).

“Dirty” in cramped compartments

German submariners

fought in almost all the oceans and seas of our planet, and, despite the fact that Germany lost the war, its submarines during World War II managed to earn the formidable reputation of a dangerous enemy.

This was facilitated by the good training of the crews, the reliability of their submarines, and the correct strategy and tactics of their use. In addition, one of the most important factors contributing to the effective performance of combat missions was good nutrition for submariners. Who and how provided breakfast, lunch and dinner for the underwater corsairs? If you ask a former German submariner about food on a submarine, you will hear the following answer: “Food? The food was good - if you like the taste of diesel fuel"

. Interestingly, despite the fact that food on submarines had a terrible reputation, formed by stories of moldy food, saturated with the smell of diesel fuel, Kriegsmarine submariners had one of the best rations in the Wehrmacht.

However, supplying high-quality products is only half the battle, since in order to turn them into tasty food, the skillful hands of a good cook were needed, or, as he is called in the navy, cook, who played a very important role on the submarine. Unfortunately, in the history of German submarines, cookers have been unfairly neglected. We know a lot about famous submariners, successful attacks on convoys and warships, but workers in tiny galleys remain aloof from these achievements. Let's try to pull them out of the shadow of the loud glory of the German submarine aces and try to answer the question: who are the cooks and what did they do on submarines?

"Disturbance"

Before starting the story about cooks on submarines, it is worth giving an explanation of what cooks did in the German merchant and navy as a whole. The cook was a very important member of the crew, and he had great responsibility. He compiled a menu for the crew for the duration of the voyage, ordered and purchased food. The filling of the provision rooms with everything necessary depended on the correctness of his calculations, since they were limited in the capacity of products, and additional supplies at sea from outside were a rare case. Therefore, among other things, the cooks were well aware of the practice of storing food on the ship.

Kriegsmarine food warehouse. On it, the boat's navigator received provisions according to a list drawn up by the cook

Of course, while on the ship, the cook’s direct responsibility was to prepare food. Every day he fed the crew breakfast, lunch and dinner throughout the voyage. In addition to standard meals, the cook was responsible for preparing small portions of hot food for those taking over the shift at midnight. The number of cooks on a ship depended on the size of the crew. On small ships, where the cook was alone, a sailor off duty was given to help him.

In the German Navy, cooks, in addition to performing their direct duties, were also included in the combat schedule. Thus, during exercises or in battle, the cook in most cases was at the disposal of the ship's infirmary as a hospital orderly. But such functionality was assigned to him only on large ships. In smaller units of the fleet, the cook could be included in the naval or technical division.

It is worth noting that in the first half of the 20th century, cooks in the German fleet were called “Smut” or “Smutje”. This nickname comes from the word "Schmutz", which means "dirty" or "dirty" in German. The use of this nickname was considered a joke, which quickly caught on and became the name for cooks. It is curious that over time this nickname has changed its interpretation, and on modern German ships cooks are called “chiefs”, and the use of the old nickname can be considered an insult.

Cook on a submarine

Only two crew members were not on watch on the German submarine: the ship's commander and the cook. This does not mean that they rested more than others; on the contrary, they slept the least, since they had many responsibilities. While the responsibility for the ship and crew did not allow the commander to fully rest, the cook practically did not sleep a wink for other reasons:

1. Organizing more or less decent food for 50 hungry young and healthy people, at least three times a day. This process included not only the constant preparation of food, but also required the cook to be an excellent restaurateur and have an analytical mind. First, the cook compiled a menu for all days of the trip, then calculated the number of products that might be needed, and passed the list to the boat's navigator, who was responsible for receiving products from the warehouse and delivering them to the boat. As an example, we can cite excerpts from the menu for six weeks at sea, compiled by the cook from the submarine U 518 (type IXC). Below are the lunch and dinner dishes that began each first day of a new week of the submarine's voyage. Breakfast was always monotonous and consisted of coffee or cocoa, milk soup with crackers, jam, honey, butter or eggs on request:

- 1st day of the hike: lunch - soup, mashed potatoes, liver, fresh fruit, dinner - spicy blood sausage, smoked meat, bread, butter, coffee;

- 7th day of the hike: lunch - fried sausage, potatoes, sauce, cabbage, fresh fruit, dinner - herring salad, beef and raw smoked sausage, bread, butter, tea;

- 14th day of the hike: lunch - soup, spinach with eggs, potatoes, stewed fruit, dinner - ham, radish, bread, butter and rosehip juice;

- Day 21 of the hike: lunch - soup, pasta with ham, sauce, pudding with juice, dinner - noodle soup with beef, cold ham, bread, butter and apple juice;

- Day 28 of the hike: lunch – potato salad, scrambled eggs, mixed stewed fruit, dinner – pasta with ham, tomato sauce, rosehip juice;

- 35th day of the hike: lunch - soup, beef stewed in onions, potatoes, gravy, vegetables, pudding with juice, dinner - ham, hard-boiled eggs, bread, butter, cocoa;

- Day 42 of the hike: lunch - pea soup with beef and pork, dinner - according to the remaining provisions.

2. Availability of ready-made coffee at any time of the day. For those taking over the shift at night, the cook prepared coffee according to a special recipe. As former U 505 crew member Hans Goebler recalled, it was a powerful stimulant: “Around midnight, Anton “Tony” Kern, our boat’s cook, came up to the bridge with a coffee pot containing his signature mixture of very strong coffee and rum. He guarded this coffee pot like a hawk, since the tasty black brew was very popular with the entire crew, regardless of whether the submariners were on watch or not.”

Galley on the U 995 submarine – sink and dressing table (contemporary photo by Pavel Kharitonov)

3. Checking the quality of products and identifying spoiled ones in order to avoid food poisoning among the crew. The process was quite difficult. Meat and vegetables were stored in a refrigerator in the galley, but other provisions were stored throughout the boat. Canned goods were located in the diesel and bow compartments, sausages hung in the central compartment and in other places where there was enough height to hang them. Potatoes were given any free space that could be found. As a result, in order to inspect the products, the cook had to “travel” throughout the submarine.

4. Washing dishes on your own or with someone’s help 24 hours a day. The cook had to do this in a tiny galley for the entire time the boat was at sea, that is, during a voyage of 4–6 weeks or even more.

On the left is an electric stove manufactured by Brown Boverie et Cie in the galley of the boat U 995 (contemporary photo by Pavel Kharitonov). On the right is a view of the galley of the prototype of the German II series boats, the Finnish submarine Vesikko. On the starboard side behind a metal rail there is a polished wooden box. There is a small niche between the box and the wall. There was a stove on which food was prepared, and plates were placed on the polished box itself, into which the cook poured or placed hot food. At the top you can see the cutout of the hatch through which supplies got onto the boat (contemporary photo by Sergei Babushkin)

5. The cook had to keep his finger on the pulse of the crew’s mood, be the person on whom the team’s spirit depends, and support it for as long as possible with high-quality and tasty food, especially on long trips. It can be said that the actions of the cook were often a real remedy against the routine that reigned on the boat during the trip. However, his very person served as a lightning rod for the bad emotions of the submariners, since the “troublemaker” often became the target of the crew’s jokes and witticisms. In addition, the cook had the honorable duty of preparing something special for birthdays and holidays, as well as the responsibility for providing the team with alcohol on the orders of the commander.

6. During a combat alert, the cook had to provide assistance to torpedomen or artillerymen.

Galley and cook's berth

Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine exactly where the cook’s resting place was located on the submarine. On several occasions he is known to have slept in the forward compartment, which served as living quarters for half the crew. For example, during the famous voyage of Günter Prien's U 47 to Scapa Flow in 1939, the resting place of Friedrich Walz's boat cook was located there. On modern German submarines, the “smutje” has a separate bunk, which is never occupied by anyone else. This makes practical sense in terms of hygiene, but it is not known whether this rule existed on submarines during the Second World War.

The galley of the American submarine Bowfin (Balao class) during World War II. It is clear that the equipment of the American cook’s possessions cannot be compared with the ascetic possessions of the German “troublemakers” (photo by Evgeniy Skibinsky)

The galley was the cook's workplace and was located differently on different types of boats. On small boats of the II series, the galley was located between the central and diesel compartments. On Series VII submarines, the galley was located in the non-commissioned officers' living quarters in front of the diesel compartment. It was a very noisy place, connecting the central post with the electric motor and diesel compartments and, due to the constant noise, din and running around, was nicknamed “Potsdamer Platz” by submariners. However, this location of the galley was convenient, since next to it was one of the two latrines of the “seven”, which was also used for storing provisions.

On Series IX boats, the galley was also located in the non-commissioned officers' compartment, in front of the entrance to the officers' living quarters. Unlike the "seven", where the non-commissioned officer's compartment was fourth from the bow, on the "nine" it was second. Therefore, the galley on the "nine" was separated from the diesel compartment by the central post and the officers' compartment, which made it a quieter place than on the "seven".

To understand what the galley on a German submarine was like, let us turn to its description compiled at the US Navy shipyard in Portsmouth in July 1946 while studying German Type IXC submarines that surrendered to the Americans after the surrender of Germany (translation by E. Skibinsky):

“BRIEFLY ABOUT THE GALLEY

Food equipment is limited; everything that is outside the galley is the tables and dishes in the battery compartment, as well as the personal pots and cutlery of the lower ranks.

The galley is located in front of the central post and the officers' mess, separating the latter from the petty officers' quarters.

In the galley on the left side of the aisle there is a small refrigerator and a cabinet for ready-made provisions, and on the right there is an electric stove, a soup warmer, a sink with drain, a tank for boiling water, a cutting board and cabinets.

The refrigerator is the size of an American household one, for a detailed description see section

S59 [description not given in translation - author's note].

The electric stove is a small unit made of cast and sheet steel, partially enameled, and can be equipped with one of the following two lists:a) three burners on top and a tank for boiling water behind the oven, two cabinets below;

b) four burners on top, oven below.

Note: in the second case, the electric stove is attached to the top of the cabinets, and the boiling water tank is a separate device.

Burners in two sizes. The larger one has a three-position heating regulator up to 3000 watts, the smaller one has three heating positions up to 1200 watts.

Ovens are different for different electric stove options. In one case the dimensions of the oven are 11.8 x 15.7 x 13.7 inches, in the other 7.9 x 23.6 x 19.7 inches, both have three heating elements of 250 watts each at the top and bottom, which with three positions The heating controller gives a maximum power of 1500 watts.

The boiler in the tank is 1200 watts, the tank itself has a volume of 10 liters (2.6 gallons). If the tank is installed separately, then with the same volume it has a boiler power of 2000 watts.

The 40-liter (10.6-gallon) soup warmer has an 8,800-watt heating element built into the base with three-position heat control, a sealed lid with a safety valve (allowing it to be used as a pressure cooker), and a spigot at the bottom for dispensing the contents.

The sink is a small single enameled steel thing with a metal (on some ships wooden) drainer.

It has a hand pump that supplies cold or warm water to the mixer tap (as on LCT-type landing ships), while the second tap can supply hot sea water when the diesel engines are running.

In the galley there are bread bins, colanders, ladles, sauce spoons, strainers, a cutting board, a manual meat grinder, a variety of pots and pans for cooking and frying, frying pans, pressure cookers, knives, scrapers, chef's forks, a cleaver, measuring spoons, a can opener, an opener and egg beater.Cutlery consisted of bowler hats for the lower ranks and a fairly elegant set of silverware, crystal, china and tablecloths for officers. In the last category, not a single boat that surrendered could boast of a standard naval set; Apparently, the shortage was “compensated” from hotels, restaurants and other establishments.

In the wardroom there is a special cabinet with nests and holders for cutlery.

Although dining tables are shown in the drawings, on the capitulating submarines in Portsmouth they were present only for the needs of the petty officers.

Conclusion:

The galley, with a total area of 27.5 inches x 4.11 feet (including the center aisle), is cramped. If you consider that all the cooking and washing of dishes for 48 people takes place in this square, you can get an idea of the cramped conditions prevailing there.

The electric stove does not allow feeding the crew as on American submarines. The dimensions and geometry of the oven only allow for baking potatoes; there is no question of any baked, fried or smoked food for the entire crew.

A large soup warmer and numerous pots and pressure cookers indicate a diet consisting primarily of boiled or steamed food.

A sink with accessories belongs in a small summer cottage.

If the tables and benches shown in the drawings of the torpedo compartment were indeed absent everywhere, then in this case the conditions for eating by the crew look more than primitive.

The location of the galley was chosen, apparently, so that food would not have to be carried far.”

Based on the above, we can say that the Americans were surprised by the ascetic conditions for eating food and the inconvenience of preparing it on a German submarine. In general, it is worth noting that this asceticism and inconvenience did not prevent the cook from working effectively, or the crew from eating, and did not affect the successful completion of combat missions.

Preparation of cooks

Almost nothing is known about the system of selection and training of cooks in the German submarine. In order to have at least some idea of how this system worked, it is worth paying attention to the details of the biography of those cooks from German submarines that were found out. Here, for example, is the story of the “troublemaker” U 995 of sailor Willi Leonhardt:

The crew of the submarine U 31 (type VIIA) having lunch on the upper deck (pre-war photo)

He was born in 1925. His father was a cook who died on a sailing ship that crashed off Cape Horn in January 1930. Willie began to study cooking at the Kaiserhof Hotel in Braunschweig, where in the fall of 1942 he was sent to serve six months of labor under the laws of the Third Reich. In April 1943 he was drafted into the navy. For three months, Leonhardt underwent initial military training, after which he was sent to Brest to the base of the 9th Submarine Flotilla for practical training.

His ability to cook was noticed while he was serving, and he was allowed to cook for the flotilla personnel. In the fall of 1943, Willie was seconded to the Wilhelm Gustloff, which at that time served as a school for the rank and file of the submarine fleet. After completing training, in the summer of 1944, Willy was sent to a cook training course in the town of Zeven, located near Bremen. After completing the courses, in the fall of the same year Leonhardt was sent to Norway to Trondheim, which at that time served as the base for the 13th submarine flotilla. There he became a cook, working in the flotilla kitchen and in the rest house for submarine crews.

The crew of a small boat of the II series takes food in the bow compartment

In December 1944, Willy was seconded to Narvik at the disposal of the newly created 14th Submarine Flotilla. There he received a position as a trainee cook on the U 995 and was apprenticed to the boat's permanent cook, Peter Feigenbutz, whom he replaced in the galley during the latter's rest. The internship lasted until March 1945, after which Willy Leonhardt was officially included in the personnel lists of the 14th Flotilla as cook U 995. Leonhardt met the end of the war in this position.

From the biography of cook U 995, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- you could become a cook if you had experience in cooking while still “in civilian life”;

- the selection site for future cooks could be the kitchens of the combat and training units of the submarine;

- future cooks took general submariner training courses;

- Cook training courses at the training center lasted one to two months;

- After completing these courses, the young specialist completed an internship on a submarine with its current cook.

If we compare these conclusions with the nuances of training cooks for submarines in the modern German fleet, we can conclude that the system of selection and training of submarine cooks has not undergone significant changes since the time of Dönitz. Currently, only certified cooks are selected to serve in the galley in the German Navy. Before they get on a submarine, they still undergo preparatory courses for cooks and training courses for submariners.

On the left is the cook in the galley of the submarine U 35 (type VIIA). On the right is U 145 (type IID) in Finland. There are dishes from the submarine's galley on the walkway.

Based on the needs of the German submarine fleet during World War II and the huge number of submarines put into operation, the number of cooks on the submarine at that time could fluctuate between 1000–1500 people. Most likely, the system for selecting and training cooks for submarines worked effectively, since cases in which the performance of a combat mission by a German submarine was disrupted due to food, as well as any mass poisoning due to poor-quality food, were not recorded.

Summing up the story about cooks on German submarines, we can say the following. The duties of a submarine cook were not very different from what cooks did on surface ships and vessels of the German fleet - of course, adjusted for the specifics of the service. The work of a “troublemaker” on a submarine was hard, and the galley worker had to literally be a two-wire worker, because he worked there alone, and there was no replacement for him. It is quite difficult for one person to carry out such a volume of work, and, one must assume, submariners who were off duty were periodically appointed as assistants to the cook.

In general, we can say that the cooks successfully coped with their duties, and this had a positive effect on the combat potential of the submarine, since the crew received good food during long voyages. Therefore, the hard work of the “troublemaker” on the submarine undoubtedly contributed to the successful actions of German submariners during the war.

On the left, a cook in the galley of a Series VII boat prepares food for the crew. On the right, submarine ace and commander of U 172 Karl Emmerman is preparing to cut a cake - a gift from the cook in honor of his awarding the Knight's Cross

In conclusion, it is worth noting another interesting fact from the life of submarine cooks. After the war, many of them had no problems finding employment. They successfully applied the experience they had accumulated during their campaigns even in famous restaurants, where they were eagerly taken. Thus, the aforementioned Willy Leonhardt became one of the most famous chefs in Brunswick, where he worked in many restaurants and in the official city residence for honored guests. Karl Dönitz, after his release from Spandau, visited the Braunschweig submariners' society three times, which gave gala dinners in his honor, the dishes for which Leonhardt prepared.

On January 6, 1981, at Dönitz’s funeral, the grand admiral was seen off on his last journey not only by his submarine aces, but also by former boat cook Willy Leonhardt, whose galley can now be seen on U 995 in Laboe. The boat is exhibited there as a museum ship.

Literature:

- Jacksch H. U 565 – Das Boot und seine Menschen – Carhistory, Moosthenning, 2006

- Malmann Showell J. Wolfpacks at War – The U-Boat Experience in World War II – Compendium Publishing, 2001

- Paterson L. U-Boat Combat Missions – Chatham Publishing, London, 2007

- Paterson L. U-Boat War Patrol – The Hidden Photographic Diary of U 564 – Chatham Publishing, London, 2006

- Ritschel H. Kurzfassung Kriegstagesbuecher Deutscher U-Boote 1939–1945 Band 1. Norderstedt

- Morozov M. Nagirnyak V. Hitler's steel sharks. Series “VII” – M.: Collection, Yauza-Eksmo, 2008

- https://historisches-marinearchiv.de

- https://de.wikipedia.org

- https://www.uboatarchive.net

- https://uboat.net

- https://www.welt.de

- https://www.weser-kurier.de

Project 667BDRM "Dolphin" nuclear submarine with ballistic missiles.

Underwater displacement 18,200 tons. Length 167 m, width 11.7 m, draft 8.8 m. Full submerged speed 24 knots. The power of the nuclear power plant is 40 thousand liters. With. Armament - 16 RSM-54 missile launchers (64 warheads), 4 torpedo tubes. Crew 130 people (including 40 officers).

Project 949A Antey nuclear submarine with cruise missiles.

Underwater displacement 24,000 tons. Length 155 m, width 18.2 m, draft 9.2 m. Full submerged speed 30 knots. The power of the nuclear power plant is 100 thousand liters. With. Armament: 24 launchers of P-700 “Granit” anti-ship missiles with a range of 550 km, 6 torpedo tubes. Crew 107 people (including 48 officers).

Premier League: what are they?

A nuclear boat has a nuclear power plant (where, in fact, the name comes from). Nowadays, many countries also operate diesel-electric submarines (submarines). The level of autonomy of nuclear submarines is much higher, and they can perform a wider range of tasks. The Americans and British have stopped using non-nuclear submarines altogether, while the Russian submarine fleet has a mixed composition. In general, only five countries have nuclear submarines. In addition to the USA and the Russian Federation, the “club of the elite” includes France, England and China. Other maritime powers use diesel-electric submarines.

The future of the Russian submarine fleet is connected with two new nuclear submarines. We are talking about multi-purpose boats of Project 885 “Yasen” and strategic missile submarines 955 “Borey”. Eight units of Project 885 boats will be built, and the number of Boreys will reach seven. The Russian submarine fleet will not be comparable to the American one (the United States will have dozens of new submarines), but it will occupy second place in the world rankings.

Russian and American boats differ in their architecture. The United States makes its nuclear submarines single-hull (the hull both resists pressure and has a streamlined shape), while Russia makes its nuclear submarines double-hulled: in this case, there is an internal, rough, durable hull and an external, streamlined, lightweight one. On Project 949A Antey nuclear submarines, which included the infamous Kursk, the distance between the hulls is 3.5 m. It is believed that double-hull boats are more durable, while single-hull boats, all other things being equal, have less weight. In single-hull boats, the main ballast tanks, which ensure ascent and submersion, are located inside a durable hull, while in double-hull boats, they are inside a lightweight outer hull. Every domestic submarine must survive if any compartment is completely flooded with water - this is one of the main requirements for submarines.

In general, there is a tendency to switch to single-hull nuclear submarines, since the latest steel from which the hulls of American boats are made allows them to withstand enormous loads at depth and provides the submarine with a high level of survivability. We are talking, in particular, about high-strength steel grade HY-80/100 with a yield strength of 56-84 kgf/mm. Obviously, even more advanced materials will be used in the future.

There are also boats with a mixed hull (when a light hull only partially covers the main one) and multi-hulls (several strong hulls inside a light one). The latter includes the domestic missile submarine cruiser Project 941, the largest nuclear submarine in the world. Inside its lightweight body are five durable housings, two of which are the main ones. Titanium alloys were used to make durable cases, and steel alloys were used for lightweight ones. It is covered with a non-resonant anti-location soundproof rubber coating weighing 800 tons. This coating alone weighs more than the American nuclear submarine NR-1. Project 941 is truly a gigantic submarine. Its length is 172 and its width is 23 m. There are 160 people on board.

You can see how different nuclear submarines are and how different their “contents” are. Now let’s take a closer look at several domestic submarines: boats of project 971, 949A and 955. All of these are powerful and modern submarines serving in the Russian Navy. The boats belong to three different types of nuclear submarines, which we discussed above.

Project 971 nuclear torpedo submarine "Shchuka-B".

Underwater displacement 12,770 tons. Length 110.3 m, width 13.5 m, draft 9.6 m. Full submerged speed 30 knots. The power of the nuclear power plant is 50 thousand liters. With. Armament: eight torpedo tubes. Crew 73 people (including 33 officers).

diesel-electric submarines

For Podplav!

The first crew of the Project 667a RPKSN "K-236"

KTOF 8 diploma 15eskpl TOF

(as of January 1, 1971)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain 1st rank | Agavelov Svyatoslav Vladimirovich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 2 ranks | Paramonov Eduard Nikolaevich | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Captain 2 ranks | Frolovsky Mikhail Serafimovich | |

| 4. | Senior assistant commander for combat control | — | —- | Add official positions |

| 5 | Assistant commander pl | Captain 3 ranks | Karpov Anatoly Alexandrovich | |

| 6 | Commander BC-1 | Captain 3 ranks | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 7 | Commander ENG | Senior Lieutenant | Znatkov Alexander Sergeevich | |

| 8 | Commander of BC-2 | Lieutenant Commander | Kosobokov Vyacheslav Aleksandrovich | |

| 9 | Commander of the GUAO | |||

| 10 | Engineer BC-2 | |||

| 11 | Commander of BC-3 | Senior Lieutenant | Marenov Boris Ivanovich | |

| 12 | Commander of BC-4 | Senior Lieutenant | Osipov S. | |

| 13 | Commander of BC-5 | Captain 3 ranks | Tsyndrenko Valery Alexandrovich | |

| 14 | Commander D-1 BC-5 | Captain 3 ranks | Oleinik Nikolay | |

| 15 | KGDU No. 1 | Senior Lieutenant | Smirnov | |

| 16 | KGDU No. 2 | Senior Lieutenant | Okhrimenko | |

| 17 | KGDU No. 3 | |||

| 18 | KGDU No. 4 | |||

| 19 | KGDU No. 5 | |||

| 20 | KGDU No. 6 | |||

| 21 | Instrumentation and automation No. 1 | |||

| 22 | Instrumentation and automation No. 2 | |||

| 23 | Instrumentation and automation No. 3 | |||

| 24 | Turbine group commander | Senior Lieutenant | Khmilyar Ivan | |

| 25 | Commander D-2 BC-5 | Lieutenant Commander | Krokhmal Eduard | |

| 26 | Commander of the ETG | |||

| 27 | Commander D-3 BC-5 | Captain-lieutenant | Shumilin Vladimir Grigorievich | |

| 28 | Head of service "X" | |||

| 29 | Head of service "M" | Senior lieutenant m/s | Tauberg Valery Mikhailovich | |

| 30 | Head of RTS | Senior Lieutenant | Gusev Stanislav | |

| 31 | Hydroacoustics group commander | — | — | |

| 32 | RTS programmer | Senior Lieutenant | Andreev V. | |

| 33 | RTS Engineer | Senior Lieutenant | Janiashvili Sergei Ivanovich |

The first crew of the K-23 submarine of project 675 KTOF

26 diploma

(as of January 1, 1968)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain 2nd rank | Mozheikin Alexander Efimovich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 2nd rank | Pylev Anatoly Ivanovich | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Captain 3rd rank | Skitovich Anatoly Egorovich | |

| 4. | Assistant commander pl | Captain 3rd rank | Katilov Anatoly Ivanovich | |

| 5. | Commander BC-1 | Lieutenant Commander | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 6. | Commander ENG | Senior Lieutenant | Gorenko Evgeniy Ivanovich | |

| 7. | Commander of BC-2 | Captain 3rd rank | Sadovy Vladimir Stepanovich | |

| 8. | Commander of the GUAO | Senior Lieutenant | Podgorny Boris | |

| 9. | Engineer BC-2 | Senior Lieutenant | Goloveshkin Lev Nikolaevich | |

| 10 | Commander of BC-3 | senior lieutenant | Tarasenko Vladimir Grigorievich | |

| 11 | Commander of warhead-4 - head of the RTS | Lieutenant Commander | Mozhaikin Yuri Alexandrovich | |

| 112 | Commander of BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Guskin Mikhail Nikolaevich | |

| 13 | Commander D-1 BC-5 | Captain-lieutenant | Korytko Ivan – Viktor Vmktorovich | |

| 14 | KGDU No. 1 | Senior Lieutenant | Shevchenko | |

| 15 | KGDU No. 2 | Senior Lieutenant | Sakharov V. | |

| 16 | KGDU No. 3 | Senior Lieutenant | Andreev Arkady | |

| 17 | KGDU No. 4 | Senior Lieutenant | Kuzmin Alexander Vasilievich | |

| 18 | KGDU No. 5 | Senior Lieutenant | Isakov Ivan | |

| 19 | KGDU No. 6 | Senior Lieutenant | Kolotov | |

| 20 | Instrumentation and automation No. 1 | Senior Lieutenant | Ehti Rudolf | |

| 21 | Instrumentation and automation No. 2 | Senior Lieutenant | Pavlov | |

| 22 | Instrumentation and automation No. 3 | Senior Lieutenant | Shandrenko | |

| 23 | Turbine group commander | Senior Lieutenant | Bogdanov | |

| 24 | Commander D-2 BC-5 | Lieutenant Commander | Korobkin Viktor Maksimovich | |

| 25 | Commander of the ETG | Senior Lieutenant | Mitrofanov Yuri Mikhailovich | |

| 26 | Commander D-3 BC-5 | Lieutenant Commander | Plygunov Viktor Mikhailovich | |

| 27 | Head of service "X" | Senior Lieutenant | Eremenko Vladimir Yakovlevich | |

| 28 | Head of service "M" | Captain m/s | Rudenko Nikolay |

List of 331 submarine crew of Project 659 KTOF

45 dipl 15 escpl

(As of January 1, 1965)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain 1st rank | Ryabov Vilen Petrovich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 3rd rank | Sofronov Alfred Pavlovich | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Captain 2nd rank | Bakhlyustov Viktor Mikhailovich | |

| 4. | Assistant commander pl | Captain 3rd rank | Smirnov Yan Serafimovich | |

| 5. | Commander BC-1 | Captain 3rd rank | Yatsenko Leonid Iosifovich | |

| 6. | Commander ENG | Senior Lieutenant | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 7. | Commander of BC-2 | Lieutenant Commander | Chernenko Vyacheslav Konstantinovich | |

| 8. | Commander of the GUAO | Senior Lieutenant | Gorelov Yuri Alexandrovich | |

| 9. | Commander of BC-3 | Lieutenant Commander | Mosolov Harold (Gorald) Viktorovich | |

| 10 | Commander of warhead-4 - head of the RTS | Lieutenant Commander | Morozov Mikhail | |

| 11 | Commander of BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Voronov Roald Efimovich | |

| 12 | Commander D-1 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Gorbarets Vasily Alekseevich | |

| 13 | KGDU No. 1 | Senior Lieutenant | Gronsky Oleg Ivanovich | |

| 14 | KGDU No. 2 | Senior Lieutenant | Panchaikin Vladimir | |

| 15 | KGDU No. 3 | Senior Lieutenant | Brovko Valentin | |

| 16 | KGDU No. 4 | Senior Lieutenant | Grenadirov Vladimir | |

| 17 | KGDU No. 5 | Senior Lieutenant | Sailors Petr | |

| 18 | KGDU No. 6 | Senior Lieutenant | Kulakov Valery Pavlovich | |

| 19 | Instrumentation and automation No. 1 | Senior Lieutenant | Golubev Vasily Alekseevich | |

| 20 | Instrumentation and automation No. 2 | Senior Lieutenant | Tolstoshkurov Leonid Andreevich | |

| 21 | Instrumentation and automation No. 3 | — | — | |

| 22 | Turbine group commander | Senior Lieutenant | Gorshkov Yuri Alexandrovich | |

| 23 | Commander D-2 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Kudryashov Viktor Mikhailovich | |

| 24 | Commander of the ETG | Lieutenant Commander | Wilson Eduard Alekseevich | |

| 25 | Commander D-3 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Petrov Vladimir Grigorievich | |

| 26 | Head of service "X" | Lieutenant Commander | Zhachkin Victor | |

| 27 | Head of service "M" | Major m/s | Shulyakovsky Yuri Mikhailovich |

List of the first crew of the submarine "K-151" project 659 KTOF

26 diploma

(as of January 1, 1966)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain 1st rank | Vasilenko Ivan Vasilievich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 3rd rank | Ivanov Nikolay Tarasovich | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Captain 2nd rank | Khukharev | |

| 4. | Assistant commander pl | Captain 3rd rank | Pylev Anatoly Ivanovich | |

| 5. | Commander BC-1 | Captain 3rd rank | Ershov Vladlen Semenovich | |

| 6. | Commander ENG | Captain-lieutenant | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 7. | Commander of BC-2 | Lieutenant Commander | Sadovy Vladimir Stepanovich | |

| 8. | Commander of the GUAO | Senior Lieutenant | Zelenko Anatoly | |

| 9. | Commander of BC-3 | Captain 3rd rank | Silin Alexander Petrovich | |

| 10 | Commander of BC-4 | Senior Lieutenant | Titov Stanislav | |

| 11 | Commander of BC-5 | Captain 2nd rank | Korshunov Leonid Sergeevich | |

| 12 | Commander D-1 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Pshenichny Alexey Matveevich | |

| 13 | KGDU No. 1 | Lieutenant Commander | Dzhumagaliev Bulat | |

| 14 | KGDU No. 2 | Lieutenant Commander | Likhomanov Alexander Grigorievich | |

| 15 | KGDU No. 3 | Captain - Lieutenant | Gubanov Leonid | |

| 16 | KGDU No. 4 | Lieutenant Commander | Okhrimenko | |

| 17 | KGDU No. 5 | Lieutenant Commander | Matyukhin Nikolay | |

| 18 | KGDU No. 6 | Lieutenant Commander | Kozlov | |

| 19 | Instrumentation and automation No. 1 | Lieutenant Commander | Safonov Anatoly | |

| 20 | Instrumentation and automation No. 2 | Lieutenant Commander | Belokon Evgeniy | |

| 21 | Instrumentation and automation No. 3 | Lieutenant Commander | Basok Yakov | |

| 22 | Turbine group commander | Senior Lieutenant | Bogdanov Igor | |

| 23 | Commander D-2 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Tour Vadim | |

| 24 | Commander of the ETG | Captain-lieutenant | Sukhov | |

| 25 | Commander D-3 BC-5 | Captain 3rd rank | Fedorov Albert | |

| 26 | Head of service "X" | Lieutenant Commander | Nefedov Boris | |

| 27 | Head of service "M" | Captain m/s | Petrov Vladimir |

Retired captain 2nd rank Ostrovsky A.I.

02/26/2010

List of crew of submarine "S-290" project 613 KTOF

19th brigade 6th squadron

(as of January 1, 1972)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain 2nd rank | Kodes Alexander Alexandrovich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 3rd rank | Vazhnikov Valentin | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Lieutenant Commander | Shubin Yuri Alexandrovich | |

| 4. | Assistant commander pl | Lieutenant Commander | Vasin Oleg Ivanovich | |

| 5. | Commander BC-1-4 | Senior Lieutenant | Komarov Boris Mikhailovich | |

| 6. | Commander of the steering group | Lieutenant | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 7. | Commander BC-3 | Captain-lieutenant | Yakovlev Yuri | |

| 8 | Torpedo group commander | Lieutenant | Bazhev Vladimir | |

| 9 | Commander BC-5 | Lieutenant Commander | Cheburakov Milan Timofeevich | |

| 10 | Movement group commander | Lieutenant | Rutberg Mikhail | |

| 11 | Head of service "M" | Captain m/s | Volkov Yuri |

List of crew of submarine "S-333" project 613 KTOF

4 obpl 6 escpl

(As of April 1, 1962)

| №№ | Job title | B/Rank | FULL NAME. | Note |

| 1. | Commander pl | Captain-lieutenant | Abramov Mikhail Borisovich | |

| 2. | Senior Assistant Commander | Captain 3rd rank | Larionov Vladimir Ivanovich | |

| 3. | Deputy commander of the submarine for watering | Lieutenant Commander | Karabchak Ivan Ivanovich | |

| 4. | Assistant commander pl | Captain-lieutenant | Terentyev Vladimir Vasilievich | |

| 5. | Commander BC-1-4 | Lieutenant | Zinchenko Petr | |

| 6. | Commander Steering group | Lieutenant | Ostrovsky Alexander Iosifovich | |

| 7. | Commander BC-3 | Lieutenant Commander | Monchenko Mikhail | |

| 8. | Torpedo group commander | Lieutenant | Filimonov Nikolay | |

| 9 | Commander BC-5 | Senior Lieutenant | Stalsky Vladimir | |

| 10 | Movement group commander | — | — | |

| 11 | Head of service "M" | Captain m/s | Danilov A. |

Performance characteristics of Projects 677 Lada and 677E Amur-1605 (export).

Surface displacement, t 1765 Length, m 67.0 Width, m 7.1 Underwater cruising range (at cruising speed, 3 knots), miles 650 Underwater cruising range (in RDP mode), miles 6000 Working immersion depth, m 240 Immersion depth maximum, m 300 Autonomy (in terms of provisions), days 45 Crew, people. 35 Torpedo armament: number and caliber of TA, mm - 6 x 533, ammunition (type) of torpedoes or anti-ship missiles - 18 torpedoes (USET-80K) and anti-ship missiles ("Club-S"), SUTA - "Moray". Anti-aircraft armament: missile system type MANPADS - "Igla-1M", number of cont. for storing ZR - 1, ammunition for ZR - 6. Radio-electronic armament: KAS - "Lithium", KNS - "Andoga", RLC - new generation, GAK - new generation with an antenna of a large effective area.

Custom search

Story

In 1966, by order of the USSR Ministry of Defense, numerous Union design bureaus began working on various technologies related to titanium and deep-sea diving. These were both titanium welding technologies and calculations for a submarine that could operate at depths of up to 1000 meters.

Why titanium? This metal has very high strength and is able to withstand water pressure even at considerable depth.

The main work on the nuclear submarine cruiser on the topic “Fin” was carried out at TsKB-18. The “Fin” theme was the design and development of materials for a deep-sea nuclear-powered hunter cruiser. Later, when designing the theme, the serial number of the project was used - 685. The intentions of the military were clear; they needed an invisible boat. At a depth of 800-1000 meters it is practically invulnerable and invisible.

The detection tools available at the time did not go that deep. This was hampered by water density, pressure and thermocline, which interfered with the acoustics.

The design of the cruiser took quite a long time. It was laid down only on April 22, 1978. On June 3, 1983, the first nuclear submarine of this project was launched. On December 28 of the same year, the acceptance certificate of APKr, serial number 501, was signed. In January 1984, the ship was assigned to the CSF. Where other “Komsomol members” also served, the diesel submarine B-4 “Chelyabinsk Komsomolets” and “Ulyanovsk Komsomolets” for example.

Many KSF submarines bore names dedicated to the Komsomol. Cities often took patronage over fleet ships, so the DPL pr. 613 “Pskovsky Komsomolets” was a sponsored ship of the Komsomol organization of the city of Pskov.

In the period from 1984 to 1987, the ship was considered experimental; it was used to gain experience in deep diving and conduct training torpedo firing from great depths. In the summer of 1984, the cruiser under the command of Yu.A. Zelensky reached a record depth for a warship - 1027 meters.

The submarine received its proper name “Komsomolets” in October 1988. But on April 7, 1989, APKr did not return from the third combat mission.