Battle in the Korea Strait

Created for long-distance ocean raids, Russian “trade fighters” were not intended for serious combat. However, fate had in store for them a fate completely different from what was expected before the war. The finest hour, which forever glorified the Russian armored cruisers Rurik, Rossiya and Gromoboy, came on August 1, 1904 - the day of the fiercest battle with the Japanese squadron in the Korea Strait.

After the start of the Russo-Japanese War, the Pacific Fleet in the Far East was divided into two parts. Its main forces were blocked by the Japanese in Port Arthur, and in Vladivostok there was a detachment of cruisers under the command of Rear Admiral Karl Petrovich Jessen. The detachment included the armored cruisers Rurik, Rossiya, Gromoboy and the armored cruiser Bogatyr.

The task of the Vladivostok detachment was to conduct the so-called “cruising war”, which consisted of operations on enemy sea lanes, intercepting transport, diverting the attention of the enemy’s main forces and, if possible, destroying his light ships. This concept was developed in case of war with Great Britain, which was heavily dependent on sea supplies. Japan is also an island state and received a significant portion of its resources from outside to wage the war. Therefore, the Russian General Staff pinned great hopes on waging a cruising war against Japan. However, the finest hour, which forever glorified the Vladivostok detachment, came during a fierce battle with Japanese armored cruisers in the Korea Strait on August 1, 1904 (in Western publications this episode is better known as the Battle of Ulsan).

Reasons for the battle

By the end of July 1904, Japanese troops occupied the Wolf Heights, located next to Port Arthur, and, having placed siege weapons on them, began shelling the harbor where the ships of the 1st Pacific Squadron were located. The ships' further stay in Port Arthur became dangerous, and on July 28, 1904, the squadron made a breakthrough, which ended in a battle with the main forces of the Japanese fleet in the Yellow Sea. The Vladivostok detachment of cruisers was supposed to come out to meet her, so that in the event of a successful breakthrough of the Port Arthur squadron, they would connect with her.

However, the message about the squadron going to sea was received in Vladivostok only on July 29. The message said: “The squadron has gone to sea, is fighting the enemy, send cruisers to the Korea Strait.”

. By this time, the battle in the Yellow Sea had already ended (the Russian squadron, having failed to break through, was partially dispersed, and the remaining ships returned to Port Arthur), but Vladivostok knew nothing about this. Vladivostok also did not know that the Japanese 2nd combat detachment under the command of Rear Admiral Kamimura, consisting of the armored cruisers Izumo, Azuma, Tokiwa and Iwate, had already entered the Korean Strait to intercept the Russians ships. In addition to the 3rd detachment, Kamimura had at his disposal light armored cruisers under the command of Vice Admiral Uriu (Naniwa, Takachiho, Tsushima, Niitaka, advice note "Quiet"), as well as destroyers. These ships were located at various points in the Korean Strait in such a way that Russian ships would not pass unnoticed. Thus, the Russian squadron walked into an already laid trap, completely unaware of it.

Armored cruiser "Rurik", 1896 Source - tsushima.su

On the morning of July 30, “Russia”, “Gromoboy” and “Rurik” went to sea (“Bogatyr” sat on the rocks back in May, tore open his bottom and was out of action until the end of the war). Having passed the island of Dazhalet and reached the parallel of Fuzana on the morning of August 1, the detachment began to wait for the “Port Arthur” ships. In the darkness, the Russian cruisers passed Kamimura's ships to the south without noticing them. Thus, the Japanese squadron found itself north of the Russian one, cutting off its path to retreat. At approximately 4:40, the fuzzy silhouettes of several ships coming from the north began to appear on the starboard side of the Russian squadron. Despite the fact that the “Port Arthur” ships were expected from the south, for some time the Russian ships still hoped that they were their own, but a few minutes later the Japanese squadron was identified by the characteristic squat silhouette of the cruiser Azuma. The lead ship under the admiral's flag was Izumo, followed by Azuma, Tokiwa and Iwate. It became clear that Kamimura had finally caught up with his victim, whom he had been hunting for a long time and unsuccessfully. The day was just beginning, the path to Vladivostok was cut off, and battle was becoming inevitable.

Before describing the battle, it is worth saying a few words about the Russian and Japanese ships that met in the Korea Strait.

Differences between Russian and Japanese armored cruisers

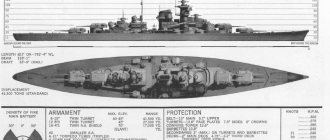

Despite the fact that the cruisers Jessen and Kamimura formally belonged to the same type, their purpose and design were different. Russian cruisers, created for the war against enemy shipping, were, in fact, huge ocean raiders (their main characteristics are given in the table at the end of the article). The strengths of Russian ships were their long cruising range and good seaworthiness - that is, purely “cruising” qualities. At the same time, much less attention was paid to “combat” characteristics, primarily defense, since it was believed that Russian cruisers were not intended for squadron combat with a strong enemy.

Armored cruiser "Russia" in the Far East Source - navsource.narod.ru

The main disadvantage of Russian ships was the weak protection of the hull and artillery. Only on the Thunderbolt, the newest and best-protected ship of the Russian squadron, most of the main and medium caliber guns were located in armored casemates. The oldest and weakest ship in the squadron was the Rurik, armed with outdated main-caliber guns. The entire protection of the Rurik guns consisted only of anti-fragmentation shields. Another weak point of the cruiser was the tiller compartment, which was not covered by the armored deck. Looking ahead, we note that this drawback played a fatal role in the fate of the ship.

Armored cruiser "Gromoboy", 1901 Source - tsushima.su

The armored cruisers of Vice Admiral Kamimura can rather be called “3rd class battleships”, since when they were created, combat rather than cruising qualities were put at the forefront. The main distinguishing feature of these ships was strong protection. The cruisers had a main armor belt along the entire waterline, above which there was another, thinner one. These two belts formed a kind of surface “citadel”, covering most of the freeboard and providing protection for the guns and mechanisms. The armament of the Japanese ships was also very powerful and consisted of four 203-mm Armstrong guns, located in two fully armored turrets along the ship's center plane - thus, all guns could simultaneously fire on one side.

Armored cruiser Iwate, 1901 Source – kreiser.unoforum.ru

Medium-caliber artillery was represented by fourteen (on Azuma - twelve) 152-mm rapid-firing guns of the Armstrong system. Ten of them (eight on the Azuma) were located in individual armored casemates, the rest were on the upper deck and covered with anti-fragmentation shields. Twelve 76-mm and eight 47-mm rapid-fire guns were supposed to repel the attacks of the destroyers. The torpedo armament of each ship consisted of four underwater onboard 457-mm torpedo tubes.

Armored cruiser Azuma, 1900 Source – kreiser.unoforum.ru

The price for the high fighting qualities of Japanese ships was their low speed and seaworthiness. Despite the fact that according to the passport the speed of the ships was 20–21 knots, in fact, according to the British attache to the Japanese squadron, they “could hardly maintain a speed of more than 18 knots for a long time.”

. In addition, the Japanese armored cruisers had very mediocre seaworthiness - the lack of a forecastle, combined with the bow, which was overloaded with armor and weapons, made them extremely “wet” and made it difficult to fire in fresh weather from the bow turret, not to mention the casemates of the lower tier . However, on August 1, 1904, the seas were minimal, allowing the Japanese to fully utilize their artillery in the battle.

Armored cruiser "Izumo" Source – kreiser.unoforum.ru

Battle August 1, 1904

At 4:35 the Russian squadron successively turned to the opposite course (east). The lead ship was the Rossiya, followed by the Thunderbolt, and the Rurik bringing up the rear. The Japanese slowly approached from the left side, gradually taking a parallel course. At 5:10, from a distance of about 60 kbt, the Japanese ships opened fire (according to Japanese data, at the moment of opening fire the distance was 45 kbt). A few minutes later, the Russian ships returned fire. Very soon the advantage of the Japanese in defense and armament began to take its toll - guns and mechanisms were damaged by shells hitting Russian ships, and people died. Fires broke out at the hit points, and at 5:23 a Japanese shell tore open the fourth smokestack on the Rossiya and broke several pipes in the boilers with shrapnel, causing the cruiser to sharply slow down.

Meanwhile, other Japanese ships approached the battle site - first the 2nd rank armored cruiser Naniwa from the detachment of Rear Admiral Uriu Sotokichi, and then the cruiser Takachiho. Both of these cruisers approached from the south and opened fire on the Rossiya. To drive them away with port gunfire, at 5:38 Jessen ordered a change of course 20° to the right. Finding itself under fire, the Naniva turned sharply to the right and stayed out of range of the Russian guns. Then Jessen decided to continue the right turn in order to take the opposite course and try to break through to Vladivostok “under the tail” of the Japanese squadron. This maneuver became fatal for the Rurik, which had already received serious damage (including an underwater hole in the stern). In order to make a turn along with the rest of the ships of the detachment, the Rurik was forced to greatly slow down. The loss of momentum, coupled with the reduced distance to the Japanese, led to a sharp increase in the number of hits on Russian ships. It was at this time that the Rurik’s steering wheel jammed due to a shell hit. At the same moment, another shell, hitting the bridge, completely demolished the steering wheel, and the ship lost control.

It was approximately 6 am. On the cruiser they managed to complete the turn, put the steering wheel straight and then tried to control the ship with the help of machines. However, soon the Rurik began to lag behind the rest of the ships of the detachment and scour its course, turning its nose towards the enemy. “Russia” and “Gromoboy”, by that time had already gone ahead by 25–30 kbt, and “Rurik” came under concentrated fire from the Japanese squadron. At 6:38, Jessen, abandoning the breakthrough attempt, ordered to turn back to cover the Rurik, giving his team the opportunity to at least partially correct the damaged steering and, together with everyone else, break through to Vladivostok.

Scheme of the battle on August 1, 1904. Source – Maritime Atlas of the USSR Ministry of Defense. Volume III. Military-historical. Part one

At about 7 o'clock, the Russian sailors began to hope that the damage on the Rurik had been repaired. For some time the ship maintained the given course and speed, rehearsing the signals given to it. At 7:20 "Russia" and "Gromoboy" turned to the northwest (to Vladivostok), but "Rurik" again began to lag behind. At 8:10, on Jessen’s command, the Russian cruisers returned again to cover the “wounded comrade.” At this moment, the distance to the Japanese was reduced to 20 kbt, and the ferocity of the battle reached its maximum. The number of hits on Russian ships grew, and their guns fell silent one after another. It became clear that “Rurik” could not follow the detachment, and the combat capabilities of “Russia” and “Gromoboy” were on the verge of exhaustion.

At 8:25, the commander of the Russian squadron decided to take the main Japanese forces north with him in the hope that the Rurik would be able to independently fight off the enemy armored cruisers, after which it would rush to the Korean coast to save the crew. Jessen's plan was a success - all four Japanese armored cruisers rushed in pursuit of the Rossiya and the Thunderbolt, leaving the Naniva and Takachiho to finish off the Rurik. It seemed to Kamimura that victory was already in his pocket, and he would be able to cope with two pretty battered Russian cruisers without any problems. But, contrary to his expectations, the Russian cruisers did not slow down, and their guns continued to fire. Due to the large number of damaged main and medium caliber guns, Russian sailors brought 75 mm anti-mine artillery into action. In addition, the Russian detachment attempted to deviate to the right, thus approaching the enemy. However, this maneuver was ineffective, since the Japanese also deviated to the right. Somewhat later, realizing that combat at a long distance did not give the desired results, Kamimura decided to reduce the distance to the enemy ships and try to finish them off.

At about 9:30, during another attempt by the Russians to get closer, the Japanese did not turn to the right, and the battle distance began to quickly close. According to Jessen, at this time the battle became especially fierce. But this effort of the Japanese did not produce results - the Russian ships, without ceasing to return fire, continued to move at the same speed and course. The fatigue of the Japanese crews began to tell - the battle had already lasted almost five hours, the rate of fire had dropped sharply, and a decisive victory was not expected. In addition, as Kamimura claimed after the battle, the ammunition on his ships began to run out, and it should have been saved for a possible meeting with the ships of the Port Arthur squadron, which could try to break through to Vladivostok. Apparently, it was these circumstances that forced the Japanese admiral to stop the battle. At 9:50, having fired the last salvo, the Izumo turned sharply to the right, and behind it the rest of the Japanese ships sequentially took a reverse course. Kamimura decided to return to the place where “Rurik” was located in order to finish it off for sure. At 10:30, the Japanese squadron disappeared from sight, and the Russian ships sounded the all-clear - it became clear that the breakthrough to Vladivostok was a success.

The death of "Rurik"

Let's return to the “Rurik” we left behind. After the ships of Kamimura and Jessen left to the north, the armored cruisers Naniwa and Takachiho remained his opponents. For an intact armored cruiser, these ships did not pose much of a threat, but now, taking advantage of the helpless state of the Rurik, as well as the fact that most of its artillery was out of action, they approached a distance from which they could accurately hit the unprotected parts of the Russian ship. By that time, Lieutenant K.P. Ivanov took command of the Rurik, since the commander of the cruiser and the officers who followed him in seniority were killed or wounded. In a last desperate attempt to drive away the enemy, it was decided to use a torpedo weapon, but the enemy shell hit the starboard torpedo tube, which was already ready to fire. A terrible explosion scattered everything on the deck, and a hole appeared in the side of the cruiser, into which, according to eyewitnesses, three horses could have driven. The Japanese ships took up a position behind the stern of the Rurik, hitting it with longitudinal fire. Taking advantage of the approach to the enemy on the next circulation, Ivanov attempted to ram the nearest Japanese cruiser, and a torpedo was fired from the surviving torpedo tube on the port side at another ship. However, the Japanese, having evaded the torpedo and ram, moved away, continuing to shoot at the Russian ship. By that time, only one 152-mm and one 47-mm gun could operate on the Rurik from time to time, and there were practically no gunners left in the ranks. Another shell interrupted the main steam lines of the Russian cruiser, as a result of which it completely lost its power. To top it all off, the enemy received reinforcements - three more armored cruisers with five destroyers approached from the south, and four returning Kamimura cruisers appeared from the north.

Realizing that all means of resistance have been exhausted, Lieutenant Ivanov decides to blow up the ship, but this was not possible, since part of the fuse cords was destroyed in the conning tower by a shell explosion, and the other was in the flooded steering compartment. Seeing that detonation was impossible, Ivanov ordered the kingstons to be opened and the cruiser to be scuttled. The order was carried out. By that time, noticing that “Rurik” was no longer shooting, the enemy also stopped firing. The Russian cruiser quickly sank into the water, falling onto the left side. The surviving sailors jumped overboard and grabbed the fragments of boards floating on the surface of the water. At half past ten, having finally shown the copper-clad ram, the Rurik sank.

The surviving Russian sailors were picked up by Japanese ships. Of the 796 sailors of the Rurik, 193 were killed and 229 were wounded, and of the 22 officers, 9 were killed and 9 more were wounded. After a stubborn and bloody five-hour battle, which the steam armored fleet had never known before, the history of the glorious “Rurik” ended. After the war, a new armored cruiser of the Baltic Fleet will be named in his honor.

Brief analysis of the battle

On August 3, the cruisers Rossiya and Gromoboy returned to Vladivostok, having previously buried the dead crew members at sea. Almost the entire population of the city came out to meet the ships. The appearance of the cruisers was terrible - chimneys pierced through, broken masts, bridges and deflectors, torn holes in the sides, traces of fires in the casemates and on the upper deck. However, according to the head of the naval department of the headquarters of the commander of the Pacific Fleet, N.L. Klado, who examined the ships, their damage was mainly superficial and did not affect vital parts. Those parts of the cruisers that were protected by armor were almost undamaged. Each of the returning ships received at least 30–35 hits from 203 and 152 mm shells.

The losses in the crews were also significant: on the Rossiya there were 48 killed and died from wounds, as well as 165 wounded; on Gromoboe - 91 killed and killed, 182 wounded. The greater number of losses on the more protected Thunderbolt is explained by the fact that, according to the regulations, on it the servants of small-caliber guns were constantly kept next to them, despite the fact that they almost did not participate in the battle. 80% of the casualties on the Thunderbolt were people who, on alert, took up positions on the upper deck, forecastle, bridges and combat tops. On the “Russia”, by order of its commander, Captain 1st Rank A.P. Andreev, the servants of the small-caliber guns were transferred to shelters on the non-firing side (these people made up for the losses in the crews of the larger guns). The second circumstance that contributed to the large number of losses on Gromoboy was the significant mortality rate of the wounded after the battle (16 people died). During the battle, the cruiser's refrigerator was damaged, and the lack of ice for the wounded during the first day after the battle in exceptionally hot weather led to an increase in mortality (at the same time, only three died from wounds on the Rossiya).

Cruiser "Russia" in Vladivostok after the battle Source - kreiser.unoforum.ru

According to Jessen's report, the consumption of shells on "Russia" and "Gromoboe" was as follows:

| 203 mm | 152 mm | 75 mm | |

| "Russia" | 189 | 567 | 372 |

| "Thunderbolt" | 158 | 1240 | 1054 |

| Total: | 347 | 1807 | 1426 |

The Japanese ships expended the following number of shells:

| 203 mm | 152 mm | 76 mm | |

| "Izumo" | 255 | 1085 | 910 |

| "Azuma" | 276 | 441 | 342 |

| "Tokiwa" | 205 | 700 | 465 |

| "Iwate" | 222 | 572 | 610 |

| "Naniva" | 370 | ||

| "Takachiho" | 186 | ||

| Total: | 958 | 4428 | 2327 |

The maximum capacity of magazines on Japanese armored cruisers was 120 shells per 203 mm caliber gun (Azuma had 80) and 150 shells for 152 mm guns. Thus, Kamimura’s armored cruisers spent only half of their main caliber ammunition in battle (except for Azuma, which fired 86% of its shells). If we compare the number of shots per gun, taking into account the fact that on Russian cruisers some of the guns were inactive, and another part was damaged, it turns out that the rate of fire of Japanese and Russian guns in battle was approximately equal, which contradicts the common myth about the fantastic rate of fire of Japanese guns.

The victory was not easy for the Japanese - their ships received more than 40 hits. True, most of the hits were from harmless small-caliber projectiles. In addition, it was affected by the fact that on Japanese ships most of the guns and their servants were protected by armor. Thus, the flagship cruiser Izumo was hit by more than twenty shells, while only two sailors on the ship were killed, and another 17 were wounded. The Azuma, which was second, received more than ten hits, and 8 people were wounded.

The third ship in the Japanese line, Tokiwa, suffered even less damage (3 people were wounded on it). But Iwate, who was at the end, received a hit that almost put an end to his career. At approximately 7:00, an eight-inch shell from the Rurik, fired from a distance of about 5,000 m, pierced the roof of the casemate of the 152-mm gun No. 1, located at the level of the upper deck. Having hit an ammunition rack located directly next to the gun, the shell caused its detonation. As a result of a powerful explosion, the casemate was completely destroyed - the armor plates fell off the side, and the gun crew was simply torn to shreds. In addition to this gun, two more 152-mm cannons failed before the end of the battle (one in the lower casemate, another installed behind the shield on the upper deck). In addition, one of the 76 mm guns was damaged. In total, as a result of this explosion, 31 people instantly died, while one officer and 13 foremen and sailors from the gun crew disappeared without a trace. In addition, seven of the wounded on the Iwata died shortly after the battle, and two more of the sixteen wounded taken ashore died in the hospital. The total losses on Japanese ships, including the armored cruisers Naniwa and Takachiho that arrived later, were 44 killed and about 80 wounded.

Destruction on the cruiser "Iwate" Source - alternathistory.org.ua

Conclusion

With the death of the Rurik, the raids of the Vladivostok cruiser detachment practically ceased. Until the fall, “Russia” and “Gromoboy” were under repair, after which an order was received from the Main Naval Headquarters:

“The ships of the Vladivostok cruising squadron should be saved for the second squadron. Cruising operations with the risk of further damage should be avoided."

On April 25, 1905, “Russia” and “Gromoboy” made their last joint raid, reaching the Sangar Strait, where they managed to sink four Japanese fishing schooners.

On May 2, 1905, a few days before the Battle of Tsushima, the Thunderbolt, having gone to sea to test a radiotelegraph, hit a mine and was undergoing repairs until the end of the war. “Russia” was left alone and did not take part in hostilities until the end of the war. Main characteristics of Russian and Japanese cruisers that took part in the battle on August 1, 1904

| Year of commissioning | Displacement, t | Speed, kt | Max. armor belt thickness, mm | 203 mm artillery* | 152 mm artillery* | 120 mm artillery* | 75- and 76-mm artillery* | Side salvo mass, kg | |

| "Rurik" | 1895 | 11 690 | 18,8 | 254 | 4/2 | 16/8 | 6/3 | – | 560 |

| "Russia" | 1897 | 12 190 | 19,7 | 203 | 4/2 | 16/7 | – | 12/6 | 496 |

| "Thunderbolt" | 1900 | 12 460 | 20,1 | 152 | 4/2 | 16/7 | – | 24/12 | 525 |

| "Iwate" | 1901 | 9750 | 20,7 | 178 | 4/4 | 14/7 | – | 12/6 | 805 |

| "Tokiwa" | 1899 | 9700 | 21,5 | 178 | 4/4 | 14/7 | – | 12/6 | 805 |

| "Azuma" | 1900 | 9953 | 20,0 | 178 | 4/4 | 12/6 | – | 12/6 | 760 |

| "Izumo" | 1900 | 9750 | 20,7 | 178 | 4/4 | 14/7 | – | 12/6 | 805 |

* – the number of guns is indicated (total/in a broadside salvo)

List of sources:

- Melnikov R.M. “Rurik” was the first.” – L.: Shipbuilding, 1989.

- Egoriev V. E. “Operations of Vladivostok cruisers during the Russian-Japanese War of 1904–1905”, M.-L.: Voenmorizdat, 1939

- Alexandrov A. S., Balakin S. A. “Asama and others. Japanese armored cruisers program 1895–1896", Naval Campaign, 2006, No. 1

- Krestyaninov V. Ya. “Cruisers of the Russian Imperial Navy 1856–1917” Part 1. – St. Petersburg, 2003

- Report from Rear Admiral K.P. Jessen on the battle on August 1, 1904. Posted on the website tsushima.su

- Illustrated chronicle of the Russo-Japanese War. The material is posted on the website tsushima.su

Until the thunder strikes...

By the time of the attack on it, the Russian Pacific squadron had already been stationed in the outer roadstead of Port Arthur for five days. She returned there after a short training trip to Cape Shantung. By the morning of February 9, the squadron's next departure to sea was planned, so the crews of several ships were busy at night replenishing coal reserves for steam boilers.

The order on mandatory blackout (darkening) was not actually observed on this ill-fated night. Due to the haste of loading, the decks of the cruiser Diana and the battleships Pobeda and Poltava were brightly lit. What can we say about the barges from which coal was loaded!

© Photo from the archive Ships of the Pacific squadron in Port Arthur before the start of the war.

All large warships of the Russian fleet had so-called mine nets. They were attached to rods located along the sides, by turning which the net was carried several meters from the side. If hit by an enemy torpedo, the explosion in the network did not lead to damage to the ship's hull.

But this time they didn’t install the nets! Really, why install them? The time was still peaceful. And it’s okay that war was expected any day now! It was still unknown whether it would start or not. And instructions from the capital categorically prohibited any actions that could be regarded by the Japanese as hostile or even simply unfriendly!

What was it? Absurd? Stupidity? Or directly provoking the enemy with his demonstrative carelessness? Let's say right away that the latter is unlikely. After all, the tsar, his ministers, and the command of the naval forces were well aware of our unpreparedness for war and tried to delay its start by all possible means. Not all methods are good, however!

The destroyers Besstrashny and Rastoropny, sent out on patrol in the evening, according to some sources, did not notice the Japanese destroyers moving towards Port Arthur; according to others, they noticed them, but, having no order to do so, did not engage them in battle. In any case, they did not give any signal about the approach of the enemy.

But the Japanese noticed them, decided that they had been exposed, and became nervous. This nervousness resulted in confusion that resulted in one Japanese destroyer colliding with another. Both were temporarily out of action and did not take part in the night attack. The remaining eight continued on their way to the goal...

© Photo from the archive

The battleship "Retvizan" is aground in the passage to the inner harbor.

Night attack

...Around midnight, the searchlight beam of the cruiser Pallada snatched the silhouettes of two approaching Japanese destroyers from the darkness of the night. Several Russian battleships and cruisers immediately saw them and, giving a signal to repel a torpedo (mine) attack, opened fire. But it was already too late!

There were four destroyers in the first wave of attackers. They fired eight torpedoes. Five either missed or did not explode, but three still hit our ships. The Pallada and, what was much worse, the newest battleships Retvizan and Tsesarevich suffered huge underwater holes.

"Retvizan" began to quickly list to the left side. The electric lighting went out. At the signal “I am in distress, I have a hole!” Lifeboats from all over the squadron rushed to the damaged ships. Fortunately, their help was not needed.

On the Pallada, the fire that arose was helped to extinguish by the water gushing inside, and then “plasters” were placed under the hole. On the Retvizan, the ammunition magazines on the starboard side were flooded and the list was reduced from 11 degrees to a safe 5 degrees.

But the “Tsesarevich” almost capsized; its roll reached a critical 18 degrees. Only thanks to the fact that the bilge mechanic P.A. Fedorov correctly assessed the situation and ordered to flood not three, as was allowed, but nine compartments on the side opposite the hole at once, the battleship was saved.

© Photo from the archive

The battleship "Tsesarevich" is the most powerful ship of the Pacific squadron.

Hurricane, but rather indiscriminate fire was opened on the Japanese destroyers from all ships of the squadron. And only on the flagship battleship Petropavlovsk the guns were silent. The spotlight beam from it shot vertically upward. This meant that the squadron commander, Vice Admiral O.V. Stark, ordered the shooting to stop!

The flagship believed that the torpedo hit the Retvizan was due to an oversight when handling the torpedo tube on one of our destroyers. At first, no other explosions were heard there against the background of the shooting that had begun. And only when reports of damage to the “Pallada” and “Tsesarevich” arrived did they finally realize that the war had begun!

The second attack group of four Japanese destroyers also fired eight torpedoes, but achieved no hits. The effect of surprise was lost, and the fire of Russian guns of all calibers did not allow the destroyers to approach a distance convenient for torpedo launches.

In fact, the Japanese commander, Admiral Heihachiro Togo, made a clear mistake by sending only ten destroyers on a night attack and ordering them to attack our ships in two waves. Imagine what could have happened if he had thrown two or three dozen of them into battle at once! And Togo had such an opportunity. But the result achieved by the Japanese was very noticeable for our squadron.

© Photo from the archive

Admiral H. Togo.

The cruisers Askold and Novik, which were belatedly sent in pursuit of the enemy destroyers, naturally did not overtake them. The Japanese did not wait for Stark to finally understand that the Russian squadron was attacked by the enemy...

First morning of the war

Even at night, the damaged ships moved to the internal roadstead. The cruiser passed without interference, but the massive battleships ran aground due to the water they had taken inside. And if the “Tsesarevich” was able to refloat quite quickly through the internal movement of cargo, then the “Retvizan” sat down tightly. For a long time it blocked half of the already narrow entrance to the harbor.

Early in the morning, Admiral Togo sent a detachment of four cruisers on reconnaissance. Based on the report of the detachment commander, Rear Admiral Dewa Shigeto, who considered the Port Arthur squadron completely disorganized and saw the strongest Russian battleships still grounded, the Japanese commander decided to attack with the main forces.

He approached Port Arthur with all six of his battleships, as well as five ironclads and four light cruisers. Our thinned squadron took the battle under the cover of coastal batteries.

© wikipedia.org

Map of the theater of the Russian-Japanese war.

The five remaining battleships, the armored cruiser Bayan and four light cruisers entered into a firefight with the enemy, which did not give any tangible results to either side. However, Togo realized that his subordinate's report was too optimistic. The hits on his ships forced the Japanese commander to stop the battle.

"Bayan" and, especially, the light cruiser "Novik" acted very boldly during the battle, rushing at the column of enemy battleships with demonstrative torpedo attacks and inviting their fire on themselves. “Novik” received one hit from a heavy shell. Thanks also to the actions of the Bayan and Novik crews, our main forces almost equally opposed an enemy twice their number.

But still this morning battle was indecisive on both sides. The Japanese shot a little better, but were unable to inflict any heavy damage on the Russian ships. Ours also scored several hits, which did not in any way affect the enemy’s combat effectiveness. That's where we parted ways.

© Photo from the archive

Vice Admiral O.W. Stark.

Vice Admiral Stark acted competently in the morning, much more confidently than on the ill-fated night. He, however, was immediately “appointed” as the main culprit of what happened. And completely unfair! He only carried out orders and instructions that tied him hand and foot, and did not have the authority of Stepan Osipovich Makarov, who in those years alone in the Russian fleet could afford to ignore the unreasonable orders of his superiors.