The submarine is capable of launching ballistic missiles

USS

George Washington

is the lead boat of the first class of ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) of the United States Navy.

George Washington

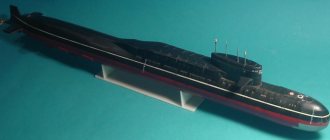

was the first operational nuclear strategic deterrent missile system fielded by the Navy. Soviet nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine Project 667BD (Delta II class)

Ballistic missile submarine

is a submarine capable of deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with nuclear warheads.

The United States Navy's hull classification symbols for ballistic missile submarines are SSB

and

SSBN

—

SS

denotes a submarine (or submersible), the

B

denotes a ballistic missile, and

N

denotes a nuclear-powered submarine. These submarines became the main weapon in the Cold War due to their nuclear deterrent potential. They can fire missiles thousands of kilometers from their targets, and the sound dampening makes them difficult to detect (see Acoustic signature), making them a credible deterrent in the event of a first strike and a key element of the policy of mutually assured destruction of nuclear weapons. containment.

The deployment of SSBNs has been dominated by the United States and Russia (since the collapse of the Soviet Union). Smaller numbers are served in France, the UK, China and India.

CONTENT

- 1 History 1.1 SSBN Sources

- 1.2 Deployment and further development

- 1.3 Poseidon and the Trident I

- 1.4 Trident and Typhoon submarines

- 1.5 After the Cold War

- 4.1 US and UK

- 10.1 Quotes

Bibliography[edit]

- Chant, Chris (2005). Submarine warfare today

. Leicester, UK: Silverdale Books. ISBN 1-84509-158-2. OCLC 156749009. - Chinworth, William K. (15 March 2006). The Future of the Ohio Class Submarine (PDF) (MS thesis in Strategic Studies). Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania: US Army War College. OCLC 70852911.

- Genat, Robert; Genat, Robin (1997). Modern submarines of the US Navy. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-7603-0276-6. OCLC 36713050.

History[edit]

| Examples and perspectives in this section may not reflect the general view of the subject . |

The first sea-based missile deterrent force was a small number of cruise missile submarines (SSG) and conventionally powered surface ships, deployed by the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s, with Regulus I missiles and Soviet P-5 Five missiles ( SS-N-3 Shaddock), both land attack cruise missiles that could be launched from surface submarines. Although this force served until 1964 and (on the Soviet side) was reinforced by Project 659 nuclear submarines (Echo I class), they were quickly eclipsed by SLBMs and nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) from 1960 onwards. [1]

Origins of SSBNs[edit]

The I-400 class submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy are considered the strategic predecessors of today's ballistic submarines, especially the Regulus missile program begun about a decade after World War II. [2] The first country to employ ballistic missile submarines (SSBs) was the Soviet Union, whose first experimental SSB was a converted Project 611 diesel submarine (Zulu IV class) equipped with a single ballistic missile launch tube in its sail. This submarine launched the world's first SLBM R-11FM (SS-N-1 Scud-A, naval modification of the SS-1 Scud) on September 16, 1955 [3].

Five additional submarines of projects V611 and AV611 (Zulu V class) became the world's first operational SSGNs with two R-11FM missiles each, entering service in 1956–57. [4] These were followed by a series of 23 specially designed Project 629 SSBs (Golf class), built from 1958–1962, with three vertical launch tubes built into the sail/tail of each submarine. [5] The original R-13 (SS-N-4) ballistic missiles could only be launched with the submarine on the surface and the launch tube raised to the top, but these were followed by the R-21 (SS-N-5) from 1963. launched from a submarine.

The world's first operational nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) was the USS George Washington with 16 Polaris A-1 missiles, which entered service in December 1959 and conducted the first SSBN deterrent patrols from November 1960 to January 1961 . [6] The Polaris missile and the first American SSBNs were developed by the Special Projects Office under the command of Rear Admiral V.F. "Red" Raeborn, appointed Chief of Naval Operations by Admiral Arleigh Burke. George Washington

was redesigned and rebuilt early in construction from the Skipjack-class fast attack submarine, USS

Scorpion.

, with a 40 m (130 ft) long missile compartment welded to the center. Nuclear power was a decisive advance, allowing a ballistic missile submarine to remain undetected at sea, remaining submerged or sometimes at periscope depth (50 to 55 feet (15 to 17 m)) throughout its patrol.

A significant difference between American and Soviet SLBMs was the type of fuel; all American SLBMs were solid fueled, while all Soviet and Russian SLBMs were liquid fueled, with the exception of the Russian RSM-56 Bulava, which entered service in 2014. With more missiles on one American SSBN than on five Golf class boats, the Soviet Union quickly fell. lags in sea-based deterrence capability. The Soviets were only a year after the US with their first SSBN, the ill-fated K-19 of Project 658 (Hotel Class), entered service in November 1960. However, this class carried the same three-missile armament as the Golf. The first Soviet SSBN with 16 missiles was Project 667A (Yankee class), the first of which entered service in 1967, by which time 41 SSBNs had entered service in the United States, dubbed the "41 for Freedom". [7] [8]

Deployment and further development[edit]

The short range of early SLBMs dictated their basing and deployment locations. By the late 1960s, the Polaris A-3 was deployed on all American SSBNs, with a range of 4,600 kilometers (2,500 nmi), a significant improvement on the 1,900 kilometers (1,000 nmi) range of the Polaris A-1. The A-3 also had three warheads that landed in a pattern around a single target. [9] [10] The Yankee class was initially equipped with the R-27 Zyb (SS-N-6) missile, with a range of 2,400 kilometers (1,300 mi).

The United States had much better luck with its bases than the Soviet Union. Due to NATO and US ownership of Guam, US SSBNs were permanently deployed to forward conversion positions at Holy Loch, Scotland; Rota, Spain; and Guam by the mid-1960s, which resulted in shorter transit times for patrolling areas near the Soviet Union. With two rotating crews on an SSBN, about one-third of all U.S. forces could be in the patrol area at any time. Soviet bases in the Murmansk area in the Atlantic and in the Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky area in the Pacific required their SSBNs to make a long passage (through NATO-controlled waters in the Atlantic) to patrol areas in the middle of the ocean in order to endanger the continental US (CONE ).

This resulted in only a small percentage of Soviet troops occupying patrol areas at any time, and was a great incentive for Soviet long-range SLBMs, which would allow them to patrol close to their bases in areas sometimes called "deep bastions". The R-29 "Vysota" series missiles (SS-N-8, SS-N-18, SS-N-23) were equipped with projects 667B, 667BD, 667BDR, 667BDRM (Delta I - Delta IV classes). [11] The SS-N-8, with a range of 7,700 kilometers (4,200 nmi), entered service on the first Delta-I boat in 1972, before the Yankee class was completed. Total 1972–1990 43 boats of all types of the Delta class entered service: SS-N-18 of the Delta III class and R-29RM Shtil (SS-N-23) of the Delta IV class.[12] [13] [14] [15] The new missiles had increased range and eventually multiple independently targetable vehicles (MIRVs), multiple warheads that could each hit different targets. [eleven]

The Delta I class had 12 missiles each; the rest have 16 missiles. All Deltas have a high superstructure (also called a shroud) to accommodate their large liquid-propellant rockets.

Poseidon and the Trident I [edit]

Although the US did not introduce any new SSBNs from 1967 to 1981, it did introduce two new SLBMs. Thirty-one of the 41 original American SSBNs were built with larger diameter launch tubes to accommodate future missiles. In the early 1970s, the Poseidon (S-3) missile entered service, and 31 SSBNs were converted to it. [16] "Poseidon" offered a powerful RGVV with up to 14 warheads per missile. Like the Soviets, the US also wanted a longer-range missile that would allow SSBNs to be deployed in CONE. In the late 1970s, the Trident I (C-4) missile was converted to carry 12 Poseidon submarines. [17] [18] The SSBN base at Rota, Spain, was decommissioned, and the King's Bay Naval Submarine Base in Georgia was built for the Trident I military forces.

Submarines Trident and Typhoon[edit]

USS Alabama, an Ohio-class submarine (also known as Trident).

Both the United States and the Soviet Union introduced larger SSBNs designed for the new missiles in 1981. The American large SSBN was the Ohio class, also called the "Trident submarine", with the largest SSBN armament of 24 missiles, originally Trident I, but built with much larger tubes for the Trident II (D-5) missile, which entered service in 1990 year. [19] [20] The entire class was converted to use the Trident II by the early 2000s. When the USS Ohio began sea trials in 1980, the two American Benjamin Franklin-class SSBNs had their missiles removed in accordance with SALT treaty requirements; the remaining eight were converted to attack submarines (SSNs) by the end of 1982. All of them were in the Pacific Ocean, and the SSBN base on Guam was liquidated; Ohio class boats

used new Trident facilities at Naval Submarine Station Bangor, Washington.

Ohio

-class boats had entered service , [21] four of which were converted to cruise missile submarines (SSGNs) in the 2000s as required by the START I treaty.

Project 941 (Typhoon-class) SSBN.

The Soviet large SSBN was the Project 941 Akula, better known as the Typhoon class (not to be confused with the Project 971 Shchuka attack submarine, which NATO calls the Akula). The Typhoons were the largest submarines ever built, with a tonnage of 48,000 tons. They were armed with 20 new R-39 Reef (SS-N-20) missiles. Six Typhoons were commissioned between 1981 and 1989. [22]

Post-Cold War[edit]

Construction of new SSBNs stopped for more than 10 years in Russia and slowed in the United States with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in 1991. The US quickly retired the remaining 31 old SSBNs and some were transferred to other functions, and the base at Holy Loch was dismantled. Most of the former Soviet SSBNs were gradually decommissioned in accordance with the provisions of the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Agreement until 2012. [23]

Russian SSBNs then included six Delta IVs, three Delta IIIs, and a lone Typhoon used as a test bed for new missiles (the Typhoon-unique R-39s were reportedly retired in 2012). Upgraded missiles such as the R-29RMU Sineva (SS-N-23 Sineva) were developed for the Deltas. In 2013, the Russians commissioned the first Borei-class submarine, also called the Dolgoruky

"by the name of the lead ship.

By 2015, two more were commissioned. The class is intended to replace aging Deltas and carries 16 RSM-56 Bulava solid-fuel missiles with a claimed range of 10,000 kilometers (5,400 mi) and six MIRV warheads. The US is designing a Columbia-class submarine to replace the Ohio-

; and expects to begin construction in 2022.

In 2009, India launched the first of its indigenously built Arihant-class submarines. [24]

Performance characteristics of Project 941 Akula submarines

Speed (surface)…………..12 knots Speed (underwater)…………..25 knots (46.3 km/h) Operating diving depth…………..400 m Maximum diving depth………… ..500 m Navigation autonomy…………..180 days (6 months) Crew…………..160 people (including 52 officers)

Overall dimensions of Project 941 “Shark” boats Surface displacement…………..23,200 t Underwater displacement……..48,000 t Maximum length (according to waterline)………….8 m Maximum hull width… …………23.3 m Average draft (according to waterline)…………..11.2 m

Power plant: 2 pressurized water nuclear reactors OK-650VV, 190 MW each. 2 turbines 45000-50000 hp each. each 2 propeller shafts with 7-bladed propellers with a diameter of 5.55 m 4 steam turbine nuclear power plants of 3.2 MW each Reserve: 2 diesel generators ASDG-800 (kW) Lead-acid battery, item 144

Armament Torpedo and mine weapons…………..6 TA 533 mm caliber; 22 torpedoes: 53-65K, SET-65, SAET-60M, USET-80. Missile-torpedoes “Waterfall” or “Shkval” Missile weapons…………..20 SLBM R-39 (RSM-52) or R-30 Bulava (project 941UM) Air defense…………..8 MANPADS “Igla”

Purpose[edit]

Further information: Second Strike and Nuclear Triad

| In this section do not cite any sources . |

Ballistic missile submarines differ in mission from attack submarines and cruise missile submarines. Attack submarines specialize in engagements with other vessels (including enemy submarines and merchant marine), while cruise missile submarines are designed to attack large warships and tactical targets on land. However, the main task of a ballistic missile is nuclear deterrence. They serve as the third pillar of the nuclear triad in countries that also operate nuclear ground-launched missiles and aircraft. Accordingly, a ballistic missile submarine's primary mission is to remain undetected rather than aggressively pursue other vessels.

Ballistic missile submarines are designed to be stealthy to avoid detection at all costs, which makes nuclear power, which allows virtually all patrols to be conducted underwater, very important. They also use many noise-reducing design features, such as anechoic tiles on the hull surface, carefully designed power units, and mount-mounted equipment to dampen vibration. The stealth and mobility of SSBNs offer a credible means of deterring an attack (by maintaining the threat of a second strike), as well as the potential of a surprise first strike.

Weapons [edit]

Main article: Submarine-launched ballistic missile

USS Sam Rayburn showing hatches for UGM-27 Polaris missiles

In most cases, SSBNs typically resemble attack submarines of the same generation, with extra length to accommodate SLBMs, such as the Russian R-29 (SS-N-23) or NATO-fielded and American-made Polaris, Poseidon and Trident-II missiles . Some early models had to surface to fire their rockets, but modern vessels typically launch while underwater at a keel depth, typically less than 50 meters (160 ft). The missiles are launched upward with an initial velocity sufficient to cause them to explode above the surface, after which their rocket motors fire, beginning the characteristic parabolic climb of a ballistic missile. Compressed air ejection, later replaced by gas and steam ejection, was developed by Captain Harry Jackson of Rear Admiral Raborn's Office of Special Projects when a proposed rocket elevator proved too complex. [25] Jackson also received an armament of 16 missiles, which were used in many of the George Washington-class SSBNs in 1957, based on a compromise between firepower and hull integrity. [26]

Terminology[edit]

United States and Great Britain[edit]

SSBN

is the United States Navy hull classification mark for a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine.

[27] SS

stands for "submarine" or "submersible", the

B

stands for "ballistic missile", and

N

stands for "nuclear powered."

The SSBN

designation is also used in NATO under STANAG 1166.[28]

In the US Navy, SSBNs are sometimes referred to as fleet ballistic missile submarines, or FBMs. In US naval slang, ballistic missile submarines are called " boomers"

.

In Britain they are called bombers

.

[29] In both cases, SSBN submarines operate on a two-crew concept, with two full crews—including two captains—called Gold

and

Blue

in the US,

Starboard

and

Port

in the United Kingdom.

France[edit]

French Navy commissions first SNLE

, for

Sous-Marin nucléaire Lanceur d'Engin

(lit. "nuclear powered submarine launcher").

The term applies both to ballistic missile submarines in general (for example, "British SNLE" occurs [30]) and, technically, as a specific classification of the Redoutable class. A later class of Triomphant is called SNLE-NG ( Nouvelle Génération

, "New Generation"). The two crews used to maximize boat availability are called "blue" and "red" crews.

Soviet Union/Russia[edit]

The Soviets called this type of ship SSBN

[31] (lit. "strategic missile submarine cruiser").

This designation was applied to the Typhoon class. Another designation used is PLARB

(

PLARB

is a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, which translates to "Nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine"). This designation was applied to smaller submarines such as the Delta class. After peaking in 1984 (following Able Archer 83), the number of Russian SSBN deterrence patrols has declined to the point that there is less than one patrol per year per submarine and, at best, one submarine patrolling at any time. Consequently, the Russians do not use multiple crews on a boat. [32]

India[edit]

India classifies this type of submarine as a strategic nuclear attack submarine.

submarine. [33]

Replacement [edit]

Main article: Columbia-class submarine

The US Department of Defense anticipates a continued need for sea-based strategic nuclear forces. Ohio SSBNs is expected to

will be decommissioned by 2029, [42] so the replacement submarine should be seaworthy by then.

Replacement could cost more than $4 billion per unit compared to Ohio

's $2 billion.

[3] The US Navy is exploring two options. The first is a variant of the Virginia-class nuclear submarines. The second is a dedicated SSBN, either with a new hull or based on a major overhaul of the current Ohio

.

[ citation needed

]

In 2007, in collaboration with Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding, the US Navy began a cost control study. [42] Then, in December 2008, the US Navy awarded Electric Boat a contract to design the missile bay to replace the Ohio

for up to $592 million.

Newport News is expected to receive about 4% of the project. In April 2009, US Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates said that the US Navy should begin such a program in 2010. [3] The new vessel was scheduled to enter the design phase by 2014. If a new hull design was to be implemented, the program would need to be launched by 2016 to meet the 2029 deadline. [42] [ update required

]

Columbia class

was officially designated on December 14, 2016 by Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, and the lead submarine will be USS Columbia (SSBN-826). [43] The Navy wants to purchase the first Columbia-class boat in fiscal year 2021. [44]

Active classes [edit]

Chinese Navy Type 094 submarines

- France

Class Triomphant - 4 in service

- Arihant class - 1 in service, 1 in testing, out of 4 planned. [34] [35]

- Type 092 submarine - 1 in service

- Borey class - 4 active [ link

]

- Avangard class - 4 in service

- Ohio class - 14 in service (4 converted to cruise missile submarines).

Photos of Project 941 Akula submarines

The length of the Project 941 Akula submarine compared to a football field

TRKSN TK-12 "Simbirsk" project 941 "Shark". The third submarine of this series is being scrapped.

TRPKSN TK-20 "Severstal" project 941 "Shark". The sixth submarine in this series.

TRKSN TK-208 “Dmitry Donskoy” of project 941 “Shark”. The first submarine from this series.

TK-17 "Arkhangelsk" project 941 "Shark". The fifth submarine of this series.

TRKSN TK-202 pr. 941 “Shark”. The second ship in the series. July 1990 Arctic 87 gr. north latitude

TRKSN TK-13 project 941 “Shark”. The fourth submarine of the series is being scrapped

Source

Pensioners[edit]

French SNLE Le Redoutable

France

- Redoutable class

/ Soviet Union / Russia

- Zulu V class (with one Zulu IV prototype) (diesel engine)

- Golf I class (diesel)

- Golf II class (diesel)

- First class hotel

- II class hotel

- Yankee class

- Yankee II degree

- Delta I class

- Delta II class

- Typhoon class (3/6)

United Kingdom

- Resolution class

United States

- George Washington class

- Ethan Allen class

- Lafayette class

- James Madison class

- Benjamin Franklin class

These five classes are collectively referred to as the "41 for Freedom".

Links[edit]

Quotes [edit]

- Gardiner & Chumbley 1995, pp. 352-353, 549, 553-554.

- Zimmer, Phil (2017-01-05), "Japan's Submarine Carriers", warfarehistorynetwork.com

- Wade, Mark. "R-11". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Large Submarines - Project 611". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Ballistic Missile Submarines - Project 629". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Man and FBM: US Navy Deploys Its First Polaris Ballistic Missile Submarines" on YouTube

- Gardiner & Chumbley 1995, p. 403.

- "Nuclear ballistic missile submarines - Project 667A". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- Jump up

↑ Friedman 1994, pp. 199–200. - Polmar 1981, pp. 131-133.

- ^ ab Gardiner and Chamblee 1995, pp. 355–357.

- "Nuclear ballistic missile submarines - Project 667B". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Nuclear ballistic missile submarines - Project 667BD". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Nuclear ballistic missile submarines - Project 667BDR". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Nuclear ballistic missile submarines - Project 667BDRM". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- Friedman, p. 201

- Gardiner & Chumbley 1995, p. 553.

- Jump up

↑ Friedman 1994, p. 206. - Jump up

↑ Friedman 1994, pp. 206–207. - Gardiner & Chumbley 1995, p. 554.

- Gardiner & Chumbley 1995, p. 613.

- "Nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarines - Project 941". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Examination" . Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "India's Nuclear Submarine Dream, Many Miles Still to Come". Reuters

. July 31, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2011. - Jump up

↑ Friedman 1994, p. 194. - Jump up

↑ Friedman 1994, pp. 195–196. - "SECNAVINST 5030.8" (PDF). US Navy. November 21, 2006 Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- "Glossary of NATO abbreviations used in NATO documents and publications (AAP-11)" (PDF). NATO. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- "Submarine Service - Royal Navy". Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "SNLE-NG Le Triomphant". netmarine.net. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- SSBN Strategic Missile Submarine Cruiser

(Strategic Missile Submarine Cruiser) - "Russian SSBN fleet: modernization, but not much". Federation of American Scientists. May 3, 2013. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- "INS Arihant Completes India's Nuclear Triad, PM Modi Congratulates Team". The Economic Times

. 2018-11-06. Retrieved September 15, 2022. - Diplomat, Saurav Jha, The. "India's Undersea Deterrent". Diplomat

. Retrieved May 13, 2016. - “Commissioning of INS Kalvari delayed | Asian Century". Asian Century

. Retrieved October 16, 2016. - “Does China Have an Effective Sea-Based Nuclear Deterrent?” . ChinaPowerCSIS. December 28, 2015.

- https://www.janes.com/article/50761/us-upgrades-assessment-of-china-s-type-094-ssbn-fleet

- “Economie de la mer. SNLE 3G: la mise en chantier prevue pour 2023". ouest-france.fr

. Retrieved June 23, 2022. - "From India Today: A look at India's top-secret and most expensive defense project - nuclear submarines". India today

. Retrieved November 3, 2022. - Diplomat, Saurav Jha, The. "India's Undersea Deterrent". Diplomat

. Retrieved May 19, 2022. - Roblin, Sebastien (2019-01-27). "India is building a deadly army of nuclear-powered missile submarines". National interest

. Retrieved September 2, 2022. - “New successor submarines named” (press release). Gov.uk. October 21, 2016. Retrieved October 21 +2016.

- "New nuclear submarine gets famous naval name". BBC News

. October 21, 2016. Retrieved October 21 +2016. - "Q&A: Replacing the trident". BBC News

. November 11, 2006 archiving from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006. - "The Future of the UK's Nuclear Deterrence" (PDF). Defense Department . December 4, 2006 archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- Jump up

↑ Weinberger, Sharon Weinberger Sharon (May 11, 2010).

"Five Major Pentagon Programs in Crosshairs". Aol News

. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on May 14, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2010. - Chavannes, Bettina. "Gates Says US Navy Plans Unavailable". At The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Unnithan, Sandeep (23 July 2009). "Deep Impact". indiatoday. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ↑

Williams, Rachel (February 16, 2009).

"Nuclear submarines collide in the Atlantic". The keeper

. London. Retrieved February 16, 2009. - "Nuclear submarines collide in the Atlantic". BBC News

. February 16, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

Sources [edit]

- Friedman, Norman (1994). US Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated History of the Design

. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-260-9. - Gardiner, Robert; Chamblee, Stephen (1995). Conway's World Warships 1947–1995

. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55750-132-7. - Miller, David; Jordan, John: Moderne Unterseeboote

. Stocker Schmid AG, Zurich, 1987, 1999 (2. Auflage). ISBN 3-7276-7088-6. - Polmar, Norman; Nuth, Jurrien: Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navy, 1718–1990

. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1991. ISBN 0-87021-570-1. - Polmar, Norman; Moore, K. J. (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of American and Soviet Submarines, 1945–2001

. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-594-1. - Polmar, Norman (1981). American submarine. Annapolis, MD: Marine and Aviation Publications. pp. 123–136. ISBN 0-933852-14-2.