The last battleships in battle

Like many other ships, the Väinämöinen-class battleships did not live up to the hopes placed on them. They did not have to defend their shores, and their only attempt to participate in an offensive operation ended in painful failure. The history of the participation of these battleships in World War II once again confirmed: it is not enough to build a successful and balanced warship - we must also provide it with the conditions for successful use.

Armadillos go into battle

Since entering service, both battleships have served in Finnish waters. Already in the fall of 1934, an accident occurred on the Ilmarinen: the ship ran aground in the Gulf of Bothnia on the approach to Vaasa, and a leak formed in the second engine room.

Subsequently, the ships served in the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Bothnia, making several visits to Sweden, including Stockholm. Only at the beginning of 1937, the Väinämöinen made a long voyage to England to take part in the naval parade in Spithead on the occasion of the coronation of George V. Already in the open part of the Baltic, the ship’s insufficient seaworthiness was evident: south of Gotland, the Väinämöinen even had to resort to towing by a Swedish battleship "Queen Victoria".

"Väinämöinen" in Copenhagen, May 25, 1937. forums.airbase.ru

By the beginning of the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940, the ships were on the Åland Islands, forming a flotilla of battleships. “Ilmarinen” was commanded by captain 2nd rank Ragnar Göransson, who was also the commander of the flotilla; "Väinämöinen" - captain of the 2nd rank A. Raninen. It was officially believed that they would ensure the defense of Aland from the Soviet landing, and at the same time strengthen the air defense of Turku - in fact, the Finnish command simply sought to keep their most valuable ships away from the enemy.

The Finnish command was cautious for good reason: already in the operational plan of the Red Banner Baltic Fleet (KBF) dated November 23, 1939, two Finnish battleships were indicated as a priority target for submarine forces and aviation - simply because the Finnish fleet did not have other large objects. Already on November 30, on the first day of the war, two flights of DB-3 bombers from the 1st mine-torpedo regiment of the 8th bomber brigade flew to Aland to search for battleships. Major E.N. Preobrazhensky's team managed to locate the battleships near the island of Ruissalo; the planes did not score any hits, although two or three bombs landed next to the ships.

Then the weather turned bad, and the next strike (two DB-3s) was delivered only on December 19, when the ships crossed into the Airisto Strait, leading to Turku. It was followed by raids on December 20, 21, 23 and 25, the latter involving 25 SB bombers and expending thirty 250 kg and sixty 100 kg bombs. In this “Christmas” raid, a hit was finally achieved in the stern of the Ilmarinen: one sailor was killed and several more were injured.

Diagram and internal structure of the Väinämöinen-class coastal defense battleships in 1940. suomenkuvalehti.fi

Until the end of the war, three more raids were made on the battleships stationed in the port of Turku (February 26 and 29, as well as March 2), but they were again ineffective. In total, over 60 tons of bombs were dropped on battleships throughout the war; according to pilot reports, one FAB-100 hit was recorded. At the same time, three Soviet aircraft were shot down. It turned out to be extremely difficult to hit the ship from a horizontal bomber, and the skerry area and ice cover did not allow the use of torpedo-carrying aircraft. The ships' anti-aircraft weapons and their control system turned out to be very powerful, roughly corresponding in effectiveness to a light cruiser of that time. Finnish battleships gained a reputation among Soviet pilots as dangerous and invulnerable ships.

Summer of '41

On June 25, 1941, at 2:37 a.m., the Red Banner Baltic Fleet headquarters announced to the fleet the start of war with Finland. The first task assigned to naval aviation (1st, 57th and 73rd air regiments) was the destruction of Finnish coastal defense battleships; airfields and ships in Turku were designated as backup targets. On the same day, the battleships were discovered and attacked by Soviet aircraft in the area of the island of Flisse, but to no avail. On June 27, a ship identified as the Väinämöinen was seen by Soviet aerial reconnaissance near the Grohar lighthouse, and the next day both battleships were spotted in the Turku area.

If during the “Winter War” coastal defense battleships showed themselves only as air defense weapons, then in July 1941 they used main-caliber artillery in battle for the first time. Already on the night of July 4 (at 1:47), standing near the island of Ørø, both ships fired at the city and port of Hanko from a maximum distance of 30 km, adjusting the fire on the water tower. To prevent the ships from falling under Soviet air raids, the shelling was very short: “Ilmarinen” fired 10 shells, “Väinämöinen” (now commanded by captain 3rd rank O. Koivisto) - 8. Several shells fell in the city, where four houses burned down (Soviet troops suffered no damage). During the day, the battleships were attacked by a pair of I-153 fighters, and in the evening 14 bombers flew to Hanko, but they did not find the battleships and bombed Finnish positions on the isthmus.

The Finns carried out the next shelling of Hanko on the night of July 12; the day before, the battleships were discovered by Soviet aerial reconnaissance near Berge Island northwest of Hanko. The shooting was again carried out from the area of Örö island, this time the Finns chose the airfield as a target, as well as the railway battery on Cape Uddekatan. This time both ships fired 38 shells.

The Soviet command experienced an acute shortage of twin-engine bombers, so only two SBs were sent against the Finnish battleships. In the evening they discovered one battleship at anchor off the island of Hogsar, but the attack was unsuccessful. The next day, the battleships were discovered by aerial reconnaissance near the island of Erê. According to Soviet data, on July 16 they again shelled Hanko harbor, and a fire broke out on the tugboat KP-1.

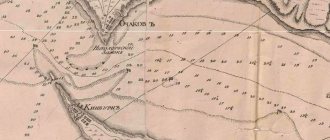

The mouth of the Gulf of Finland and the middle part of the Baltic Sea. Chronicle of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union on the Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga. Issue 1

On July 20, Soviet aerial reconnaissance discovered both battleships southwest of Kimito Island heading north. Six Ar-2 dive bombers were sent to attack him; the pilots reported hits, but in reality the attack was unsuccessful. Late on the same day, one battleship was spotted off Felervik, and a second one off Sande Island. The next day, the battleships were spotted in the area of the islands of Corpo and Lille Nagu, on July 22 they were noted in the same place, and on the 23rd they were again attacked by six Ar-2s (the pilots reported that the bombs exploded 15-30 m from the side) . The attacks continued on July 24.

On July 26, the Ilmarinen stationed near the island of Öre took part in repelling the Soviet landing on the island of Bengtskär, while it was attacked by Soviet aircraft near the island of Ére (the pilots reported being hit by two 100-kg bombs). This time the battleship actually received some damage: one sailor died, the ship was taken to Turku for repairs.

"Ilmarinen" in the skerries near Turku, July 28, 1941. sa-kuva.fi

Fearing for the fate of the ships, the Finns temporarily stopped using them against Hanko. However, they themselves explain the break by preparing special high-explosive shells for firing along the shore. One way or another, the next shelling of the peninsula took place only on September 2. This time it was longer: each ship fired 34 254 mm shells. The fire was fired from a distance of 15-18 km; according to Finnish data, a Soviet ammunition depot was destroyed.

Operation Nordwind

At the beginning of September 1941, the Germans began preparations for landing on the Moonsund Islands. The invasion was carried out through the Muhu Väin Strait from the occupied territory of Estonia, but in order to divert Soviet troops to the defense of the western and northern coasts of the archipelago, it was decided to simulate an attack on the islands by a fleet operating from Finnish bases. The operation was designated “Nordwind” (“North Wind”).

At first, the Finns decided to limit their participation in the operation to a new shelling of Hanko. On 7 September at 13:13, the commander of the Finnish naval forces in Turku received the following order from the fleet command:

“The Germans will launch an attack on the islands of Hiiumaa and Saaremaa on 11.9. Your task is to confuse the enemy. Prepare to gather ships near Utö and move coastal defense battleships to the Bengtskär area to attack enemy forces near Hanko."

The gathering of ships was planned at the edge of the skerries near the island of Utö, which lies 45 miles southwest of Turku and the same distance west of Hanko. However, Major General Väino Valve, who exercised overall command of the Finnish coastal defense and naval forces, did not accept the fleet's plan to attack Hanko, since it did not fit into German calculations. Valve ordered, together with the Germans, to move in a different direction - south from Utö, towards the island of Hiiumaa.

Captain 2nd Rank Eero Rahola (left) and Commander of the Finnish Coastal Defense Forces Major General Vaino Valve, September 5, 1938. uusisuomi.fi

On September 8, German ships arrived at Utö Island, and the next day Finnish forces arrived here - both battleships, three icebreakers, two escort ships and tugs with barges. It was decided that the ships would go only 30 miles to Hiiumaa, while the Finnish minesweepers were ordered to trawle at a distance of up to 15 miles. Some works mention that the initial plan for the raid was a diversionary landing at the Ristna lighthouse (on the western tip of Hiiumaa) with up to a battalion of forces.

The meaning of the participation of battleships in this exit is unclear: the formation included Finnish icebreakers that had similar sizes and a very similar appearance. The battleships could fire at Hiiumaa from a maximum distance of 15 miles, but this required traveling not 30, but 40 miles, and not to the south, but to the southeast of Utö.

As a result, the exit was cancelled, the German ships remained near Utö, and the Finnish ones went to the island of Högsara west of Hanko. Meanwhile, on September 8, the Germans landed on the island of Vormsi in the Muhuväin (Moonzund) Strait and completely occupied it on September 10. After this, the Soviet command should have assumed that the enemy was preparing an invasion of the Moonsund Islands from the mainland. On September 14, a landing was planned on the island of Muhu (Moon), connected by a dam to the island of Saaremaa (the main one in the archipelago).

However, the German command did not abandon the diversionary operation. Perhaps this happened because three false attacks from the sea were planned at once (including Westwind and Zuidwind), and the Germans did not want to ruin the already planned scheme. The Finns agreed to resume the operation, but according to the new plan, the ships were supposed to go only 25 miles south of the island of Utö. The gathering was scheduled for the afternoon of September 13th. At 10:15, the small ships stationed near Attu Island weighed anchor, and at 10:45, the battleships stationed at Hogsar. Having united near the island of Vänö, the ships moved west along a skerry fairway past the islands of Borstö and Jurmo. Shortly after noon they arrived at the gathering place north of Utö.

The German-Finnish naval formation consisted of three detachments. The first included both battleships, as well as four Finnish patrol boats (VMV-1 and VMV-14–16). The second detachment was German: it included the minelayer Brummer (1300 tons), the tugboats Typhoon and Monsun, as well as the 3rd flotilla of patrol boats (VP 304, VP 305, VP 308, VP 313 and VP 314) . The third detachment consisted of landing craft: the largest Finnish icebreakers Tarmo (2400 tons) and Jaakarhu (4800 tons), as well as the small transport Aranda (600 tons).

Icebreaker "Sibiryakov", former Finnish "Jaakarhu". Basic data on standard ships of the Ministry of the Navy. Quick reference. L., 1956

In the morning, Finnish auxiliary minesweepers went out to sweep the planned route of the formation, and around noon, 20 miles from Utö, for an unknown reason, one of the trawls broke. The plan of operation was changed: the ships were to move from Utö to the south at a course of 189°, but after 17.5 miles turn west to a course of 232° and move like this for another 7.5 miles. At half past eight in the evening we had to turn around and head back to Utyo. Now the formation was not even approaching Hiiumaa, and it is unlikely that the enemy could even notice its exit.

The death of "Ilmarinen"

At 17:50 the formation weighed anchor and moved south. The first was the flagship Ilmarinen, on which was the commander of the Finnish fleet, Captain 1st Rank Eero Rahola. The Väinämöinen was moving 800 m behind him. Both battleships walked with paravans, and Finnish patrol boats were placed on both sides of them, carrying anti-submarine protection. Following, at a much greater distance, were the German ships: the Brummer, and behind it both icebreakers. Note that the German patrol boats formed a more correct order: one moved in front of the minesag, two on the sides and slightly in front of it, two more behind. Finally, the ships of the landing group brought up the rear.

Thus, the Germans were primarily concerned with protecting the ships of their detachment. The Finns showed extreme carelessness by placing the largest and most valuable ships at the head of the column. In 1940, two 15-knot minesweepers (Ruotsinsalmi and Riilahti) were built specifically to accompany them, but at that moment they were busy laying mines in the Gulf of Finland. Other minesweepers could not go with the squadron due to insufficient speed.

Ilmarinen leads the German-Finnish column in Operation Nordwind. The photo was taken from the battleship Väinämöinen. On either side of the flagship are patrol boats. sa-kuva.fi

At 17:50 the German-Finnish formation weighed anchor, and at 18:15 the lead ship passed the Utö lighthouse. The ships sailed at a speed of 11 knots: the old Tarmo could not give more. The column moved on a course of 189° and stretched for 5 miles. The weather was cloudy and there was a swell in the sea, but overall visibility was good. The coal-fired icebreakers smoked heavily. The ships diligently conducted active radio communications, attracting the attention of Soviet radio intelligence.

At 19:00 it began to get dark, and at 19:51, 17.5 miles from Utö, the Ilmarinen, according to plan, turned southwest and set course 232°. The column followed him. Soon after the turn, the sailors noticed something was wrong with the right paravane: its cable, instead of going away from the ship, ran along the side and then disappeared under the water. However, they did not choose a paravan; the movement was not stopped.

At 20:30 the Ilmarinen gave a light signal to turn back. At this point, the ships had traveled 24 miles from Utö Island. The battleship began to turn to the right. At 20:31, when the ship had already turned about 40°, a double explosion occurred near its left side in the area of the aft deckhouse. According to eyewitnesses, the shock from it was nothing more than a broadside salvo of the main caliber, and on the German ships the explosion was not heard at all.

Apparently, the explosion occurred closer to the bottom of the ship. He tore apart not only the side of the ship under the armored belt, but also the bulkhead between the diesel compartment and the compartment with the propeller electric motor on the left side. The longitudinal bulkhead did not save us; the nearest compartments on the left side began to quickly fill with water.

General progress of Operation Nordwind. "Gangut", issue No. 25

“Ilmarinen” retained its speed and control, but began to quickly sink with its stern and list to the left side. Captain 2nd Rank Göransson gave the order to turn further to the right - apparently in order to somehow straighten the roll. However, this did not help: at 20:35 the roll was already 45 degrees. For a while, it seemed that the capsizing slowed down, but a minute later the battleship lay down on the port side, and its battle top touched the water. People jumped overboard, some tried to escape to the bottom of the ship. At 20:38, the Ilmarinen sank at coordinates 59°27'N. w. 21°15'E. at a depth of 90 m.

Finnish patrol boats were the first to rescue the crew. Lieutenant Siivo Peltonen's boat VMV-1 carried 57 people on board; He managed to remove some of them in the very first minutes right from the keel of the battleship, and their clothes were almost dry.

Of the 403 crew members and representatives of the fleet headquarters, only 132 people were saved. 271 people died: 13 officers, 11 petty officers, 65 non-commissioned officers and 182 sailors. These were mainly mechanics and artillerymen: out of 90 sailors of the artillery division, 4 people were saved, out of 80 people in the engine crew - 14. Having capsized, the battleship stayed on the water for some time, but no one was able to get out of the hull, since the portholes on the main deck were too small. Nevertheless, among those rescued were all the senior officers who were in the control room or on the bridge: fleet commander Rachola, ship commander Göransson and senior officer Wilman.

The rescue operation lasted only half an hour. At about 21:00, the German-Finnish detachment took the opposite course and already at 23:15 found itself in the skerries again.

The mystery of the death of "Ilmarinen"

Finnish radio stated that the ship died for an unknown reason, and the Sovinformburo in its evening report on September 21 reported that “the Finnish coastal defense battleship Ilmarinen in the Gulf of Finland, attacked by our ships, ran into mines and sank.”

Indeed, everything spoke of a mine explosion, but after the war it turned out that Soviet forces did not lay minefields in this place. This gave rise to the version about a mine torn from its anchor, and German and Finnish researchers, not wanting to “give” victory to the enemy, initially claimed that it was a German mine.

The explosion did not occur at the waterline, but in the depths, at the bottom of the ship. Thus, it could not have been caused by a mine floating on the surface. Therefore, versions began to appear about an “unaccounted for mine” - one of those that in the summer and autumn of 1941 was placed by Soviet “small hunters” with Hanko in small cans or one at a time without clearly recording the place of placement. This immediately expanded the circle of “authors” of the victory: in fact, it could be attributed to any boat operating in the western part of the Gulf of Finland, not excluding those based in Tallinn or Moonsund. However, the site of the explosion was 60 miles from Hanko and a hundred miles from Tallinn, and in addition, on the open sea, outside the skerries, where it made no sense for Soviet boats to go. Soviet planes also laid mines somewhat to the north, in the skerries on the approach to Turku. There was no point in mining the open sea with a small number of mines.

The last campaign of "Ilmarinen" and the location of Soviet minefields at the mouth of the Gulf of Finland. Modern Finnish scheme. forums.airbase.ru

And yet, on the way of the German-Finnish formation there really was a Soviet minefield. It was deployed by the patrol ships “Tucha” and “Sneg” on August 5, 1941 at the edge of the skerries 8 miles south of Utö Island and was designated 26-A. In total, 60 mines of the 1926 model were placed in one line with an interval of 60 m. Moving at a speed of 11 knots, the German-Finnish formation crossed the line of this obstacle at 19:05. The probability of an explosion when crossing the barrier almost at a right angle was low (27.5%), however, with paravanes installed, the possibility of catching one of the mines with a paravan was close to one. Apparently, such a mine hit one of the paravanes of the lead battleship, but instead of cutting it with a cutter, the paravan caught the mine, tore it off the anchor and dragged it along with it.

Let us remember that shortly before 20 o'clock the sailors of the Ilmarinen noticed problems with the paravane - not with the left one, but with the right one. If the mine were in the left paravane, then when turning right, the ship would inevitably pull it to the port side, and not at the level of the waterline, but under the bottom. However, when turning sharply to the right, the right paravane is also pressed against the side. If he really caught the mine, it is possible that it was pulled to the starboard side after the first turn, and during the second it was dragged under the bottom of the ship to the other side, where it hit the side with an incoming stream of water, after which the mine exploded.

Alert drill on the battleship Väinämöinen, June 20, 1942. sa-kuva.fi

The fate of "Väinämöinen"

The death of the flagship greatly influenced the Finns: now they preferred to take care of their remaining battleship. After this, the Väinämöinen fired at Hanko only once: on November 15, 1941. 32 shells were fired, and the target was again a railway battery. After this, the ship did not participate in hostilities: the war was going on too far from the mouth of the Gulf of Finland. Until Finland exited the war, the battleship did not move out of the skerries near Turku. Only from time to time he conducted anti-aircraft artillery exercises, but mostly he stood camouflaged by branches near a steep rocky shore.

"Väinämöinen" in the skerries near Turku, July 29, 1944. sa-kuva.fi

Nevertheless, he managed to once again play his role in the fighting. At the beginning of July 1944, the German command sent the air defense ship Niobe to the Gulf of Finland - an old Dutch cruiser, rearmed with eight 105-mm anti-aircraft guns, with a radar and a modern fire control system. Soviet aerial reconnaissance tracked the ship's appearance in Helsinki and its passage through the skerry fairway to Kotka, but mistakenly identified it as the Finnish Väinämöinen (the ships were almost identical in size and very similar in contours).

The destruction of the Finnish battleship became a kind of matter of honor for Soviet pilots. The first air raid on Kotka on July 12 was unsuccessful, with 3 out of 30 Pe-2 dive bombers lost. The next raid on July 16 involved 132 aircraft, including 30 Pe-2 dive bombers and 4 A-20 Boston topmasts. It was the latter who finished off the ship, successfully placing two 1000 kg bombs into it. The Niobe sank in shallow water, its crew losing 86 people killed and 89 wounded. Soviet aviation had no losses.

Comparative silhouettes of the air defense ship Niobe (above) and the battleship Väinämöinen. bellabs.ru

Even after studying aerial photographs of the attack, the Soviet pilots were confident that it was the Väinämöinen that sank. Only after the end of the war did it become clear that the battleship was safe and sound. Since the peace treaty of February 10, 1947 prohibited Finland from having large warships, the Finns could not refuse the offer to sell the surviving battleship to the Soviet Union. At first they asked for 1,100 million marks, but since the alternative was to send the ship for scrapping, the parties eventually agreed on 265 million.

As part of the Soviet fleet

The acceptance of the battleship in Pansio (just west of Turku) took place from March 1 to March 24, 1947. On April 22, the ship was included in the lists of the Baltic Fleet under the name "Vyborg", but the Finnish flag on it was replaced by the Soviet one only on June 5. Two days later, the ship moved to the Soviet base at Porkalla Udd, and was assigned to the 104th Skerries Brigade of the 8th Fleet. In the autumn of the same year he visited Leningrad.

Monitor "Vyborg" at the summer parade in Leningrad, late 40s - early 50s. forums.airbase.ru

In February 1949, the ship was reclassified from coastal defense battleships to sea monitors and transferred to the Kronstadt naval fortress. At the beginning of 1952, it was sent for repairs in Kronstadt, and a year later it was transferred to Tallinn to Marine Plant No. 7. The repair of the ship began only in 1954 and ended in August 1957, while since December 1955, the Vyborg was included in the Leningrad naval base.

Monitor "Vyborg" in Kronstadt, summer 1957. cruiser.patosin.ru

For the next year and a half, the ship was actively used in naval exercises and covered more than 2,500 miles. In January 1959, “Vyborg” was put into the first-stage reserve and placed in Kronstadt for partial conservation. Only on February 25, 1966, the ship was expelled from the fleet and disarmed, and exactly seven months later it was transferred to the Stock Property Department for cutting into metal. In total, the ship served for 33 years, of which 26 years were in active service and 7 years in reserve.

Sources and literature:

- Chronicle of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union on the Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga. Issue 1. From June 22 to December 31, 1941 M.-L.: Office of the Naval Publishing House of the NKVMF of the USSR, 1945

- Jurg Meister. Eastern front. War at sea 1941-1945. M.: Eksmo, 2005

- P.V. Petrov. Coastal defense battleships “Vainamoinen” and “Ilmarinen” // Military-technical almanac “Typhoon”, 2000, No. 12 (31)

- A.M. Vasiliev. Monitor “Vyborg” // “Gangut”, issue 25 (2000)

- Tuomo Lappalainen, “Kymmentuumaisten lumoissa” // Suomen Kuvalehti 38/2016 (23.09.2016) https://suomenkuvalehti.fi/share/936913/63f2d5

- https://karsikas.mbnet.fi

- https://www.veteraanienperinto.fi

- https://forums.airbase.ru

- https://users.tkk.fi/~jaromaa/Navygallery

Fleet of the Russian Empire after the Crimean War

Pavel Matveevich Obukhov, Russian engineer, metallurgist and artilleryman. Like many outstanding people of Russia of that time, he died early. Even if you make up a conspiracy theory...

The position in which the Russian Imperial Navy found itself after the Crimean War was very controversial. On the one hand, the victories of the “Battleship”, “Fortress” and “Kremlin” greatly increased the prestige of sailors in the empire, which was quite high before the war. Public opinion, rejoicing after successfully repelling a coalition of the world's two strongest powers "and their hangers-on" the Ottoman Empire and the traitors from the Kingdom of Sardinia [1] , strongly supported military spending. On the other hand, the country was no less exhausted by the long war than its enemies, and time was needed to recover. In addition, other changes were required - in particular, for further qualitative growth, there was a need for a radical modernization of the current technical base, which actually had to be created from scratch. The production of rifled artillery and firearms, the massive mechanization of the fleet, the construction of ships from iron hulls and vague forecasts regarding the use of steel in shipbuilding, the need for personnel training and other things - all this required separate expenses. In addition, it was during the reign of Alexander II that the so-called “agrarian revolution” began, which led to a sharp increase in the need for agricultural machinery and tools, ranging from shovels to steam tractors - and the modernization of Russian society was placed at the forefront of the entire reign of the emperor, which caused certain cutting spending on the army and navy. As a result, the construction of battleships in the first years of the reign of the new emperor was reduced to the creation of a “mobilization fleet” - the creation of a reserve of materials and the conclusion of contracts, according to which, in the event of war, the country's leading naval factories were required to build large battleships as soon as possible. The only exceptions were armored gunboats - they were built immediately, without creating a “reserve in case of war” [2] .

Meanwhile, the situation with the technical base for building a fleet was changing. First of all, shipbuilding enterprises developed in St. Petersburg itself. Before 1861, a large-scale reorganization of the city's state-owned shipyards was carried out - a single enterprise, the Admiralty Shipyards, was created, the manager of which was Vasily Stepanovich Linden, a promising administrator and talented engineer. The Admiralty Shipyards and some private factories were absorbed - in particular, the Mitchell and Byrd factories, which were experiencing problems with financing and orders. New private enterprises were also built - immediately after the end of the Crimean War, two large factories were founded in the city, Carr and McPherson [3] , and Poletiki and Semyannikov [4] . There were also changes in the regions - in particular, the Solombala shipyard in Arkhangelsk and the Nikolaev Admiralty in Nikolaev were reorganized, which contributed to their productivity in the future. The circle of contractors grew - old mechanical engineering enterprises grew, new ones appeared. The production of armor and artillery was improved - by 1860 it was possible to create and establish the production of fairly effective models of muzzle-loading rifled guns, and in 1863, with the help of the German Krupp plant, the first model of a Russian large-caliber breech-loading gun was created, after which their production was established at the newly built Obukhov plant In Petersburg.

There were also organizational changes in the Maritime Ministry itself. Created back in the 20s under Minister Menshikov [5], the Main Naval Staff was transformed into the Naval General Staff (MGSH), at the same time the powers of the “shore” command were curtailed in favor of the “operational” command - admirals now received wider freedom of action, while the MGSH acted more as a theoretical and organizational center. In 1859, the Marine Technical Committee (MTK) was created, responsible for all technical issues of shipbuilding and fleet armament. In the same year, a Marine Technical School was created in St. Petersburg, which was supposed to provide training for technical personnel for new ships, and technical training among other officers was also expanded - from now on they were required to know at least the theoretical properties of the equipment that was installed on the ship. The reorganization caused, on the one hand, a storm of protest from some officers, and full support from others. There were many problems with establishing the supremacy of power in the fleet - for the sake of this, Minister Nevsky even entered into a conflict with Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich, which, however, quickly ended. As a result, it was possible to obtain permission from the emperor to reform the command, as a result of which all naval ranks, including admiral generals, began to report to the naval ministry; As a formality, Naval Minister Nevsky was also awarded the rank of admiral general, so that Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich would not be subordinate to an officer lower in the table of ranks. All these works undermined the health of the no longer young 63-year-old Valery Nikolaevich, as a result of which in 1861 he died of a stroke right in his office. The last project that he managed to approve as Minister of Navy was a new classification of the fleet. It was at the same time simple, and at the same time reflected all the functionality of ships necessary for Russia:

– coastal defense battleships;

– cruisers of the 1st rank (frigates and screw frigates);

– cruisers of rank II (screw clippers);

– cruisers of rank III (auxiliary sailing ships without steam propulsion);

– gunboats;

– steamships;

– yachts;

– transports;

– training ships;

– port ships.

This system became the basis for the entire future “table of ranks” of ships of the Imperial Russian Navy and was developed just a few years after its introduction [6] . In addition, it reflected the main idea of the development of the Russian fleet, which dominated among sailors at that time - the battleships, which had proven themselves so well during the Crimean War, were going to be built only to protect their own shores, and cruisers of various types were intended for the open sea and oceans.

After Nevsky's death, the fate of the fleet hung in the air. Many wanted to see Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich as the Minister of Naval Affairs, while others believed that the prince had too many outside concerns besides the fleet to act as the head of all sailors. Both sides were conditionally satisfied - the post of Minister of Naval Affairs was offered to Konstantin Nikolaevich shortly after Nevsky’s death, but he refused it, citing his decision by saying that he was “too busy with other government affairs.” As a result, Nikolai Karlovich Krabbe, a rather popular man and considered a great eccentric among naval officers, became the head of the naval ministry.

Nikolai Karlovich Krabbe, naval minister of the Russian Empire in 1860-1874. It was under him that the Russian steam armored fleet began to be built, both in reality and in the alternative.

Once Krabbe heard that behind his back they called him “smart,” and he was terribly offended. - Have mercy! - he exclaimed. - Well, what kind of German am I? My father was a purebred Finn, my mother was Moldavian, I myself was born in Tiflis, in its Armenian part, but was baptized into Orthodoxy... Therefore, I am a natural Russian!

In his personal life, as well as in his service, Crabbe was distinguished by his extraordinary accessibility: for example, there were no reception rooms or antechamber in front of his office; there were no adjutants or officials on duty in his apartment; everyone went to the minister without a report, and the courier or messenger opened the doors directly to the office. Simple in his manners, somewhat eccentric in his expressions, Crabbe was always pure in soul and noble in his aspirations

...was a great hunter of all kinds of salacious stories and a notable collector of all kinds of pornography and obscenity. He sometimes brought his inexhaustible collection in parts for display, but, to the honor of His Highness (the future Alexander III), I will say that although he was young, he looked at everything in passing, perhaps only to please Crabbe, Nikolai Karlovich...

He readily took up Nevsky's cause and, having received a reformed administrative apparatus, began to carry out technical reforms. And the first thing that was raised was the question of building armored ships, although not in the form in which it was expected - in 1861, two similar type 1st rank cruisers, Sevastopol and Petropavlovsk, protected by waist armor, were laid down. By that time, military-built battleships had already begun to leave the fleet, and Russia, one of the first countries to build battleships, could be left without them altogether. Therefore, at the beginning of 1862, Nikolai Notar, the author of the project for the first Russian battleships, at the direction of Minister Krabbe, began designing new battleships.