America creates an empire

By the end of the 19th century, politicians in the United States were increasingly talking about the need for the country to emerge from voluntary isolation and implement a policy of expansionism.

President William McKinley, future President Theodore Roosevelt, and military theorist Alfred Mahan did everything they could to spread the idea of creating an American empire that would compete on equal terms with the great powers. And to become a global heavyweight, the United States needed a navy. And the fleet needed bases. Thanks to the victorious Spanish-American War of 1898, the Americans received new markets for the sale of their products, convenient harbors for the military fleet in the Philippine Manila and on the island of Oahu, as well as a transshipment base on the island of Guam and complete control over the Caribbean Sea.

Alas, along with their vast territories, the colonies presented America with a very big problem: a national liberation movement began in the Philippines.

For the Filipinos, the war with Spain, hiding behind hypocritical slogans about freedom, did not bring freedom. Only the “sign” changed: instead of a Spanish colonial official, an American one came.

Uprising continues in the Philippines

By the time peace was signed with Spain, the Philippine War of Independence had already been going on for three years. The rebel forces were led by a Chinese-born politician, Emilio Aguinaldo. Coming from a wealthy and influential family that belonged to the colonial elite, he first rebelled against the rule of Spain, and then went over to the side of the Americans and managed to fight with them.

Emilio Aguinaldo

Aguinaldo had absolutely no intention of showing submission to the new masters of the Philippines. He strove for power and did not want to share it with the “liberators.” Without serving a single day in the army, the politician proclaimed himself a general and announced the creation of the Philippine Republic.

The United States and Spain at this time had already concluded a truce and were preparing for a peace conference. Aguinaldo also acted quickly and decisively.

In the fall of 1898, in the city of Malolos, he convened the Constituent Assembly, which proclaimed the creation of an independent Philippine state. In January 1899, the Filipinos adopted a constitution and Emilio Aguinaldo became the first president of the republic.

12/08/41 – Japanese invasion of the Philippines

In Japanese plans, the operation to capture the Philippines was part of the "Great War in Southeast Asia", which also included the capture of the strategically rich Dutch East Indies, an operation against British troops in Malaya and the neutralization of the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. The capture of the Philippines was not an economic or political goal for Japan, but a mainly strategic one. If they could neutralize the American fleet based in the Philippines and American aircraft at Philippine airfields, then it would not matter to them how long US ground forces would defend the islands. The Japanese plan initially called for landing in several places and capturing the main airfields on the island of Luzon.

The combined American and Philippine forces were commanded by General Douglas MacArthur. He convinced President Roosevelt that the Philippines still needed to be protected. Prior to this, it was believed that the defense of the archipelago did not make sense due to its remoteness from the main US territory and the difficulty of supply.

The Japanese 14th Army, under the command of Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma, was assigned to invade the Philippines. Air support for the invasion was to be provided by the 5th Air Group. The total number of invasion troops was 129 thousand people. The invasion was supported by the 2nd and 3rd Japanese fleets, which included: the battleships Haruna and Kongo, heavy cruisers Takao, Atago, Tekai, Maya, Ashigara, Nachi ", "Haguro" and "Myeko", light cruisers "Natori", "Naka", "Nagara" and "Jintsu", as well as 31 destroyers, seaplanes "Chitose" and "Mizuho", minesweepers, patrol ships, minelayers and other ships. The Allied forces consisted of 13 divisions and numbered 151 thousand people. In addition, the US Asian Fleet was based in the Philippines, which included: the heavy cruiser Houston, the light cruisers Marblehead and Boyce, the air transports Langley and Childs, 12 destroyers, 28 submarines, and gunboats. , minesweepers, floating bases and other auxiliary vessels.

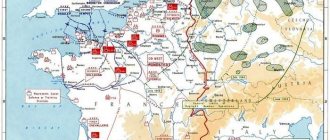

Map of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines.

The Japanese 14th Army began the invasion operation on December 8, 1941, with a landing on Batan Island. Two days later, the Japanese launched an invasion of Camiguin Island and northern Luzon. The main force began landing early on the morning of December 22 on the east coast of Luzon. On December 24, General MacArthur withdrew the bulk of his troops to the Bataan Peninsula. The capital of the Philippines, Manila, was captured by Japanese troops on January 2, 1942.

Japanese tanks advance on Manila

Philippine and American troops on the Batan Peninsula.

From January 7 to January 14, 1942, Japanese troops conducted reconnaissance and preparations for the offensive on Bataan. The Japanese 14th Army resumed its offensive on January 23, landing a battalion-sized amphibious assault from elements of the 16th Division, and then launching an offensive along the entire front line on January 27. The amphibious assault was repelled with the help of torpedo boats. The remnants of Japanese units that broke into the jungle were destroyed by hastily formed units consisting of US Air Force, Marines and Philippine police units. On January 26 and February 2, air raids were carried out against Japanese positions using the few remaining US Air Force P-40s. The last American aircraft on the peninsula were destroyed by February 13.

Japanese flamethrowers on Batan.

For several weeks, Japanese troops suspended their offensive. However, the Allies had problems with food shortages and the spread of malaria. Food supplies were designed for 43 thousand American soldiers. In total, together with Philippine troops and refugees, more than 100 thousand people ended up on the island.

On March 28, a new wave of Japanese offensive began. At the same time, the Japanese actively used aviation and artillery. Allied forces, weakened by malnutrition and disease, had difficulty containing the advance. On April 3, the Japanese broke through the defenses in the area of Mount Samat. On April 8, the 31st Infantry Division and the 57th Infantry Regiment of the American Army were defeated in the Alangan River area. The 45th Infantry Regiment was able to evacuate to Corregidor. From the defeated 31st Infantry Division, only about 300 people reached Corregidor. By April 10, Japanese forces managed to completely capture Bataan.

On Corregidor there were positions of American coastal batteries defending the entrance to Manila Bay. The 59th and 91st coastal defense artillery regiments and the 60th anti-aircraft artillery regiment were located on the island. They were easily destroyed by Japanese bombers, who were able to drop bombs from high altitudes while remaining out of reach of the island's defenders' anti-aircraft batteries.

In December 1941, Philippine President Manuel Quezon, General MacArthur, and other high-ranking military and diplomats were evacuated to Corregidor and housed in the Malinta Tunnels to avoid bombing in Manila. Since March 1942, Corregidor's communication with the outside world was maintained only through submarines. They brought mail and weapons. High-ranking Philippine and American officials, as well as senior generals, were also evacuated to them. The submarines also removed gold and silver reserves located in the Philippines and some important documents. Those who were unable to be evacuated by submarine were eventually captured or ended up in civilian concentration camps in Manila and elsewhere.

Allied headquarters in the Malinta tunnels.

Generals Wainwright and MacArthur (right).

Corregidor was defended by approximately 11,000 men from the 4th Marines and US Navy personnel who served as infantry. In addition, several scattered units from the Bataan Peninsula managed to evacuate to the island. The Japanese began their assault on Corregidor by destroying artillery batteries on May 1, 1942. On the night of May 5–6, the Japanese, with two battalions of the 61st Infantry Regiment, despite strong resistance, managed to seize a bridgehead in the northeastern part of Corregidor. After this, the Japanese units on the island were reinforced with tanks and artillery. The island's defenders were driven back to the gates of the Malinta tunnels. On the evening of May 6, General Wainwright requested Japanese General Homma to surrender. General Homma insisted that the surrender include all Allied forces in the Philippines. Wainwright accepted these demands. On May 8, he sent a telegram to all American troops ordering them to lay down their arms. However, many American soldiers disobeyed the order and continued to fight alongside the Filipino guerrillas.

The American naval base of Davao was located in Mindanao. On December 8, 1941, a Japanese force under the command of Rear Admiral Kyoji Kubo carried out an air raid on Davao. At this moment there was no American fleet at the base. In the harbor there was only the Princeton seaplane base, which, noticing the approach of Japanese aircraft, managed to escape to the south. With massive airstrikes, the Japanese completely destroyed the naval base. Until the completion of the Corregidor operation, the Japanese did not undertake major amphibious operations against Mindanao. On May 8, 1942, General Wainwright, who was stationed on Corregidor, announced the surrender of all American troops in the Philippines.

Japanese troops in the Philippines.

All the islands of the Philippine archipelago were captured by the Japanese by June 1942. Allied losses during the defense amounted to 2,500 dead, 5,000 wounded, and 100,000 prisoners. Japanese losses were 4,200 dead, 6,100 wounded, and 500 missing.

See also: Photo |

Japan. Army during the war. [Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] Share on:

The war against the Americans begins

The Americans, who just a month ago signed the Treaty of Paris (under which the Philippines was transferred to them), were perplexed.

Some local mestizo impudently proclaimed himself president and literally took away an entire colony from under the gringo’s nose. For which the American army and navy shed blood and wasted taxpayers' money.

By this time, the Yankees controlled only Manila, the capital of the archipelago. And they unwisely left the rest of the Philippines under rebel rule.

Philippine soldiers outside Manila, 1899

On the night of February 4, American sentries opened fire on troops of Filipinos approaching the bridge over the San Juan River. The next morning, Aguinaldo ordered his troops to storm Manila. But then it turned out that the rebel troops were decisively inferior to the regular US Army. Washed in blood, the Republican troops not only achieved no success, but also lost ten men for every American soldier killed or wounded.

Americans decide to fight to the end

Such betrayal by former allies made the Americans very angry. Congress—as soon as news of the uprising arrived—immediately ratified the Peace of Paris. And the rebels, led by Aguinaldo, were declared rebels. American troops were ordered to destroy the rebels as soon as possible.

In just a couple of months, the Yankees, encountering almost no resistance, occupied almost the entire territory of the republic. They captured the capital of the rebels - Malolosa. And Aguinaldo’s troops retreated to the north.

However, the American offensive stopped due to a shortage of troops.

If the forces of the expeditionary force, which had also fought with the Spaniards, were sufficient to defeat the Filipinos, then an entire army was needed to control the country.

The Americans refused to negotiate with the rebels and demanded unconditional surrender.

American soldiers in the Philippines

By summer the offensive resumed. And already in the fall, Aguinaldo’s situation became so difficult that he decided to switch to guerrilla warfare.

Return to the Philippines July–December 1944

Return to the Philippines

July–December 1944

Strategic and tactical prerequisites

The basic principles of the strategy for the further course of the war were developed at the Pearl Harbor conference in July. President Roosevelt considered two different concepts for approaching the ultimate goal - the assault on Japan itself. Admiral Nimitz argued in favor of intermediate operations in Formosa or China. General MacArthur insisted on the first liberation of the Philippines (for military and political reasons), and then a strike on Japan. Roosevelt accepted MacArthur's plan. The headquarters of the army and navy, in close cooperation, developed a consistent plan for conducting military operations: MacArthur advances on Mindanao, Nimitz on Yap. They then jointly advance on Leyte, then MacArthur invades Luzon, and Nimitz captures Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

As soon as the operation to capture the Marianas ended, Nimitz assigned Spruance and his 5th Fleet headquarters to develop a plan for future operations on Iwo Jima and Okinawa; Halsey and the headquarters of his 3rd Fleet were entrusted with the task of capturing Yap. In fact, it was simply a reshuffling of commanders and staffs; ships and parts did not change. What had previously been the 5th Fleet became the 3rd: Meacher's 58th Rapid Deployment Tactical Carrier Group became the 38th, Turner's 5th Amphibious Squadron became the 3rd, etc.

Preparatory activities

1944, September 15. Morotai and Pelelier. MacArthur lands troops on Morotai to establish an air base there to support further offensive operations, and encounters only minor resistance. Having coordinated his actions with him, Nimitz attacks the island of Pelelier in the Palau group of islands. The Marines of Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger's III Amphibious Corps (part of Vice Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson's 3rd Amphibious Squadron) meet here with stubborn resistance from the gallant defenders of the island under the command of General Sadai Inone (September 15–October 13) . At the same time, Wilkinson, using army units, storms and captures Angaur (September, 17–20), and also occupies Ulithi Atoll, 160 km west of Yap, without resistance (September, 23). The magnificent harbor on Ulithi becomes the naval base of the 3rd Halsey–Meacher Fleet. For several weeks, the clearing of scattered pockets of Japanese resistance has continued on the Palau Islands (November 25).

1944, September 15. Change of plan. In support of the American operations at Morotai-Pelele, carriers from Halsey's 3rd Fleet raid Yap, Ulithi, and the Palau Islands to neutralize nearby Japanese bases and weaken enemy defensive positions (September 6). Then they explore the Philippine coast of these islands (September, 9-13). Encountering only minor resistance, Halsey sends a message to Nimitz, recommending that the planned interim landings on Mindanao and Yap, which seem unnecessary to him, be canceled and that Leyte be stormed as soon as possible. Nimitz agrees, requests permission from the Allied Joint Headquarters, and then heads to the Quebec Conference. He offers MacArthur a “loan” of his 3rd Amphibious Squadron and 14th Army Corps. MacArthur, having received the consent of the Joint Allied Command, postpones the landing on Leyte from December 20 to October 20 and accepts Nimitz's proposal (September 15). The corresponding order is signed on the same day.

A comment . American military circles have never demonstrated the kind of initiative and flexibility that Halsey, Nimitz, MacArthur and the Unified Command demonstrated. MacArthur's bold decision to launch a large-scale amphibious operation two months ahead of schedule bordered on impudence. The headquarters did a tremendous job, solving the almost impossible task of logistically supporting the operation.

1944, October, 7-16. Preparing for the invasion. The 3rd Fleet is sent to suppress the remnants of the Japanese Air Force. While land-based aircraft from the 5th Air Force from New Guinea and the 7th from the Mariana Islands attack all enemy bases within their flight range, long-range B-29 aircraft from the 20th Bomb Squadron strike Formosa from airfields in China (October, 10). Meanwhile, Halsey cuts sea communications and bombards coastal fortifications on Okinawa and neighboring islands, and then turns south towards Formosa and Luzon (October 11).

1944, October, 13–16. Battle in the coastal waters of Formosa. Japanese aircraft provide Halsey with fierce resistance. Two of his cruisers were badly damaged and several small ships were sunk.

The Japanese radio, misled by the glow (caused not so much by burning American ships as by downed Japanese bombers), reports a great victory. Halsey, hoping to force the Japanese Combined Fleet to take active action, leaves one carrier group to escort his damaged ships and proceeds with the rest east into the Philippine Sea (October 14–15). Taking the bait, Toyoda sends 600 sea-based aircraft from Japan to Formosa airfields to complete the “defeat” of the American fleet. Halsey returns to Formosa and destroys almost half of these aircraft in two days (October 15–16). In total, during these operations, more than 650 Japanese aircraft were shot down, many were damaged, and numerous coastal structures were destroyed. The most serious loss for Japan is the defeat of the replenished and reorganized carrier squadrons. American losses amounted to 2 heavily damaged cruisers, several sunk small ships and 75 downed aircraft.

Visayas Islands Campaign

The Philippine Islands were defended by about 350 thousand Japanese soldiers under the command of General Yamashita, the conqueror of Malaya and Singapore. The defense of the Southern and Central Philippines was held by the Japanese 35th Army under the command of General Sosaku Suzuki.

1944, October, 14–19. Approaching Leyte.

A large landing armada approaches the coast of the island. It consists of 700 transports, on board of which there is a 200,000-strong landing force of the 6th Army under the command of General Krueger, part of Admiral Kincaid's 7th Fleet. Wilkinson's 3rd Amphibious Squadron and Barbie's 7th Amphibious Squadron land ashore with naval artillery support from Rear Admiral J.B. Oldendorf's squadron consisting of 6 battleships (surviving or repaired after the attack on Pearl Harbor), 4 heavy cruisers ( including the Australian Shropshire), four light cruisers and 26 destroyers. The air support group (Rear Admiral Thomas L. Sprague) consists of 16 escort carriers, 9 destroyers and 11 escort destroyers. Far out to sea (currently neutralizing Japanese Luzon air bases and guarding the San Bernardino and Surigao Straits) is Halsey's 3rd Fleet, the core of which is Meacher's 38th Rapid Deployment Tactical Carrier Group: 8 heavy and 8 light aircraft carriers, 6 high-speed battleships of a new design, 3 heavy and 9 light cruisers and 58 destroyers. The number of aircraft based on Meacher's aircraft carriers totals more than a thousand.

A comment. This magnificent landing operation was spoiled by one drawback: the command was united, but not united. MacArthur commanded Kincaid's ground forces and 7th Fleet, while Halsey, still under Nimitz's command, had to deal with the dual mission of defeating the Japanese Combined Fleet (which required going to sea) and supporting Kincaid in covering the landing. (which required approaching land). The Americans had no reason to consider these two goals incompatible. But the Japanese had a plan that the Americans did not foresee.

Plan "Sho". Having felt the full brunt of air strikes and submarine attacks on its warships and transports, Japan realized long before this moment that the American capture of the Philippines, Formosa or the Ryukyu Islands would split the Japanese Empire into two parts: the Southern Resource Zone, which served as a source of fuel and raw materials for Japan , and Japan itself. Accordingly, they developed Plan Sho (Victory), intended as a final death game in which the main card was the Japanese Combined Fleet. In principle, this plan called for the use of some of the scattered naval units to lure American carrier forces into a trap, while the rest of the Navy, concentrating on each of the new allied landing sites, would destroy enemy ships covering the landings from the sea and block those landing on shore. In principle, this plan was good, but it had one big flaw: it required a large number of aircraft, and in the battle of Formosa the Japanese lost most of their naval aviation, which had been difficult to restore. However, Toyoda hoped that land-based aviation units in the Philippines would fill this gap.

1944, October, 20–22. Landing on Leyte. After intense reconnaissance and heavy naval bombardment, the Sixth Army's 10th Corps (Major General Franklin S. Sybert) and Sixth Army's 24th Corps (Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge) begin landing. The island's garrison, consisting of the 16,000-strong Japanese 16th Division (General Tomochika), initially offers little resistance. By midnight, 132,400 soldiers and 200 thousand tons of cargo find themselves ashore, and Kincaid's squadron hurries south to the Surigao Strait to meet a possible threat from the Japanese Navy. General MacArthur, accompanied by Philippine President Sergio Osmeña, goes ashore and radios his return (October 22).

Battle of Leyte Gulf

1944, October, 17–23. Preparations. Warned of the Americans' intentions by Leyte intelligence (October 17), the Japanese immediately put Plan Sho into action. The combined Japanese fleet emerges from its widely scattered bases. Ozawa's Northern Fleet (or Japanese 3rd Fleet), consisting of 4 remaining aircraft carriers, 2 battleships, 4 cruisers and 8 destroyers, heads from Japan to Luzon to lead the US 3rd Fleet away from the landing site: Ozawa's carriers have only 116 aircraft with poorly trained pilots. Kurita's central group (2 super-battleships, 3 battleships, 12 cruisers and 15 destroyers), moving north from Malaya, Borneo and the Chinese seas, blocks the San Bernardino Strait. Southern group (or group “C”) of Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura (consisting of 2 battleships, 1 heavy cruiser and 4 destroyers from Malaya and Borneo) with the support of Kiyohide Shima’s 2nd strike group of 2 heavy and 1 light cruisers and 4 destroyers from the Ryukyu Islands) goes southeast and east through the Surigao Strait, between Mindanao and Leyte. These pincer forces of the central and southern forces would crush all US Navy amphibious forces in Leyte Gulf in a concerted attack, pinning them ashore.

1944, October, 23–24. Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. US submarines detect Kurita's central formation as it enters the Palawan Strait from the South China Sea. After transmitting a radio message to Halsey, the submarines sink 2 heavy Japanese cruisers and damage a third. Kurita, continuing to sail into the Sibuyan Sea, is attacked by Micher's 38th formation. The Japanese superbattleship Musashi was sunk after two days of continuous bombardment by aircraft carriers; several ships were damaged. Kurita turns around and heads back to the west (October 24, evening). Halsey assumes that the Japanese are retreating. Meanwhile, Japanese ground-based aircraft attack one of the units of the 38th formation. Most of them were shot down by carrier fighters, but the American light cruiser Princeton was sunk and the cruiser Birmingham was badly damaged. Unbeknownst to Halsey, Kurita changes course again and stubbornly moves towards the San Bernardino Strait.

1944, October, 24–25. Battle of Surigao Strait. Kincaid, warned of the approach of the Southern Japanese group, sends Oldendorf's squadron to intercept it. At night, reconnaissance torpedo boats discover Nishimura's squadron moving in a linear battle formation. In two swift attacks, American destroyers torpedo the Japanese battleship Fuso and 4 destroyers. Despite the disrupted combat formation of his ships, Nishimura gives the order to attack Oldendorf's squadron. She conducts a maneuver to concentrate fire on the enemy's advanced ships and sinks all of them except one destroyer. Nishimura dies along with his flagship Yamashiro. Sima's squadron, waiting for the rearguard to approach, in turn comes under attack from torpedo boats, as a result of which the Japanese light cruiser is damaged. Trying to turn away from the torpedo, Shima's flagship collides with one of Nishimura's sinking ships. Oldendorf pursues the Japanese throughout the strait. Another Japanese cruiser sinks under fire from its ships, aircraft from Admiral Thomas L. Sprague's escort carriers, and land-based bombers. The rest of Sima's ships retreat. Oldendorf, having completed his mission and knowing that his squadron can immediately withstand another battle, returns back.

1944, October 25, dawn. San Bernardino Channel. Kurita, without losing hope of connecting with Nishimura's group in Leyte Gulf, freely leaves the San Bernardino Strait and turns south. Halsey, having gathered all his forces, rushes into a trap set by Ozawa's Japanese aircraft carriers, cruising far to the north. The message Halsey received about the defeat of Kurita's group in the Sibuyan Sea on the evening of the previous day and the overly optimistic messages from his own pilots lead him to believe that Kurita was completely out of the game. Therefore (mindful of his dual task) Halsey rushes north with all available ships of the 3rd Fleet with the goal of destroying the Japanese carrier squadron. He makes the mistake of not communicating his decision to Kincaid.

1944, October 25. Morning battle near Samara. Kurita's advance to the south comes as a complete surprise to Rear Admiral A.F. Clifton. Sprague (not to be confused with Admiral Thomas L. Sprague!), commander of the escort carrier squadron of the Kincaid Landing Group, supporting Allied ground operations. With six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four escort destroyers equipped only with 5-inch guns, C. Sprague finds himself embroiled in a battle with four Japanese battleships, six heavy cruisers, and 10 destroyers. During the fierce battle, Sprague's squadrons, armed only with fragmentation bombs (to cover ground operations), launch massive attacks on Japanese ships equipped with heavy guns, while his destroyers bravely attack the enemy. As a result, Sprague and his escort aircraft carriers eliminate the threat of complete destruction hanging over him. One of its aircraft carriers, Gambier Bay, was sunk; 2 destroyers and 1 escort destroyer receive heavy damage and also sink. The remaining American ships are surrounded by Kurita's ships. But planes taking off from the aircraft carriers of other escort groups (rushing south to join Kincaid's 7th Fleet) attack Kurita's central group. Japanese victory is near, but Kurita retreats, believing that he is under attack by Meacher's 38th Carrier Group. His decision is supported by the message that Nishimura's southern group has been destroyed. Kurita initially considers rushing to Ozawa's aid, but then abandons this idea and retreats through the San Bernardino Strait. He is pursued by aircraft from Rear Admiral John S. McCain's carrier tactical group of Halsey's fleet, rushing to answer the 7th Fleet's call for assistance. Meanwhile, Admiral Thomas L. Sprague's escort carriers and Oldendorf's squadron, returning from the battle in Surigao Strait, are attacked by Japanese land-based aircraft (this is where kamikaze pilots first operate). As a result, the American aircraft carrier Saint Lo sinks and several other ships are damaged.

1944, October 25. Battle of Cape Engaño. Halsey's rush to the north to intercept the Japanese carrier squadron is crowned with success at 2:20, when Meacher's reconnaissance planes spot it. At dawn, Halsey launches the first of three successful air attacks. Ozawa, who left almost all of his aircraft ashore to attack American ground forces, has only anti-aircraft artillery at his disposal, which is not enough to withstand attacks from American aircraft. As night fell, all 4 Japanese aircraft carriers, as well as 5 more ships of the squadron, were sunk. 2 Japanese battleships, 2 light cruisers and 6 destroyers manage to escape. Halsey, enraged by the meticulous questioning of Nimitz from Pearl Harbor, demanding to explain the reason for the “impossibility of helping Kincaid,” picks up “cruising” (full) speed and sails south with most of his ships.

A comment. The four-phase naval battle of Leyte Gulf marked the end of the Japanese fleet as an organized fighting unit. 4 Japanese aircraft carriers, 3 battleships, 6 heavy and 4 light cruisers, 11 destroyers and 1 submarine were sunk. Almost every second Japanese ship participating in the battle was damaged. About 500 Japanese aircraft were shot down, and nearly 10,500 Japanese sailors and airmen were killed. American losses amounted to 1 light aircraft carrier, 2 escort aircraft carriers, 2 destroyers, 1 escort destroyer and 200 aircraft. 2,800 Americans were killed and 1,000 were wounded. A total of 282 ships took part in this large-scale battle: 216 American, 2 British and 64 Japanese. According to rough estimates, the number of human resources involved was 143,668 Americans and British and 42,800 Japanese.

Both Halsey and Kurita made a number of obvious mistakes. Halsey abandoned Leyte Gulf to pursue Ozawa, and Kurita retreated when victory was in his pocket. In Halsey's justification, it should be said that his position was complicated by the duality of the task assigned to him. He could not know that Ozawa's aircraft carriers were just a decoy. As for Kurita, he was misled by conflicting reports and shaken by two unexpected previous defeats. He did not want to risk throwing the remaining ships into the pincers of superior enemy forces. He was therefore forced to retreat, a victim of the overcomplicated Japanese war plan and his own fears.

Fight for Leyte

1944, October 21 - December 31. General Yamashita, commander of Japanese troops in the Philippines, having recovered from the sudden landing of the allied troops, decides to begin the fight for Leyte. While the veteran Japanese 16th Division carried out a skillful containment operation, Japanese reinforcements from the Japanese 35th Army rushed in from Luzon and the Visayas. From October 23 to December 11, fast destroyers, used as transports, deliver 45 thousand soldiers and 10 thousand tons of food and ammunition in small batches. But soon these sea communications are cut off by short- and long-range American air forces. The desperate resistance of Japanese ground-based aviation only leads to the fact that it is wasting most of its aircraft. By the end of the year, Japanese maritime supplies to the Leyte garrison had virtually ceased. Meanwhile, the US 6th Army slowly advances on powerful Japanese fortifications located in the central part of the mountain ranges. Further advances are stopped by tropical downpours, turning the roads into a swamp. On the right flank, the 10th Corps approaches Limón, the northern key position of Suzuki's line of defense (November 7). On the left flank, the 14th Corps storms the steep heights protecting Ormoc, the southern key position and main Japanese port. The airlift of American paratroopers (December 7) threatens Suzuki's southern flank. A desperate Japanese airborne assault to the east of the newly arrived Americans fails. Having received reinforcements, Kruger encircles both flanks (December, 7–8) and captures Limon and Ormoc (December, 10). Then the US 77th Division, advancing from the south, and the 1st Cavalry and 24th Divisions from the north meet at Libungao (Dec. 20), completing the encirclement of Suzuki's forces and cutting them off from Palompom, the last remaining port. Organized Japanese resistance ends on Christmas Day, December 25th. In this campaign, the Japanese lose 70 thousand soldiers; American losses amount to 15,584. Meanwhile, the Allies are gaining a bridgehead for the capture of Samar (late October).

1944, December 15. Capture of Mindoro.

In a daring amphibious operation, a brigade-sized tactical landing force lands on Mindoro, the northernmost of the Visayas islands south of Luzon, to establish an air base to support MacArthur's upcoming offensive on Luzon.

A comment . Japan's desire to speed up operations on the island of Leyte resulted in a catastrophic defeat of its naval and air forces, as well as a large reduction in the number of ground forces in the Philippines. By the end of the year, Japan had irrevocably lost the war. Its communications with the Southern Resources Zone were cut, the tonnage of the merchant fleet decreased from 6 million tons in 1941 to 2.5 million in 1944; 60% of the losses were caused by American submarines. About 135,000 Japanese soldiers were left cut off deep behind American lines, finding themselves in a hopeless and helpless situation. But Japan still did not want to admit defeat.

Protests against war begin in the US

At this time, the number of people dissatisfied with the fighting at the ends of the earth was growing in the States. Since the War of Independence, Americans have formed the following belief (which at the end of the 19th century still dominated public opinion): the United States does not wage wars of conquest, it fights only for freedom. Your own and other peoples. Therefore, it became increasingly difficult to explain what an army of more than a hundred thousand people was doing in the Philippines, suffering heavy losses from guerrilla warfare.

Back in the fall of 1898, the Anti-Imperialist League was created in the United States. The leadership included many influential people from former President Cleveland to the richest businessman Carnegie and writer Mark Twain.

The league's ideologists proclaimed: America should not fight to enslave other peoples; instead, it should begin to restore order on its own land.

Supporters of racial segregation joined the protests against imperialism. They feared that the emergence in the United States of territories inhabited by a large “colored” population would lead to a diminishment of the influence of the white majority.

Rallies took place all over the country, at which anti-imperialists advocated: there is no need to waste energy on the Philippines. It was proposed either to grant them independence, or to give the islands under the temporary control of a small and neutral European power, like Belgium.

However, supporters of the creation of an American empire dominated the McKinley government. The need to punish the rebels and the prospect of controlling the routes across the Pacific Ocean blinded them.

Key battle for the Philippines

Go through the Japanese, go around the Japanese, smash into the Japanese - but come to Manila!

Douglas MacArthur

The phrase “I'll be back” became famous in the United States many years before the release of the film “Terminator”. In 1942, having broken through to Australia on a torpedo boat, it was uttered by the commander of the defense of the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur. He and his troops at this time could not hold back the onslaught of the Japanese and were forced to retreat. Two years later, the general kept his word. On October 20, 1944, he stepped off a landing ship into the surf on the shores of the Philippine island of Leyte side by side with his soldiers. Gradually, island by island, the Japanese invaders were driven out of the archipelago.

General MacArthur returns to the Philippines. Leyte Island, October 20, 1944

On January 9, 1945, American troops landed on Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. The prelude to the battle for the capital of the archipelago, Manila, began.

Tanks in Luzon. Japanese look

The 2nd Tank Division of General Iwanaku Yushihara was preparing to meet the Americans in the Philippines. It consisted of about 200 tanks. Most of them were Type 97 "Chi-Ha" and "Shinhoto Chi-Ha", but there were also a number of light Type 95 "Ha-Go" and obsolete Type 89. The division already in October 44 lost two tank companies (about 30 vehicles) sent to Leyte Island to repel the American invasion.

The commander of the Japanese defense in the Philippines, General Yamashita Tomoyuki, understood perfectly well that repelling the US offensive was an almost impossible task. But he planned to delay the enemy as long as possible so that the main forces would have time to retreat to mountainous areas, where it would be much more difficult to deal with them.

On January 16, Yamashita ordered the 7th Tank Regiment to attack the American beachhead. A tank company and a motorized rifle battalion were to carry out the order. However, having advanced at night, they were ambushed by anti-tank guns and suffered heavy losses. And the next morning the Americans themselves attacked the main forces of the Japanese regiment, located in a town called Urdaneta. During the battle, one single Japanese tank platoon was lucky: these three vehicles were able to take an advantageous position and knock out two Shermans before they themselves were destroyed by return fire. The rest of the Japanese tank crews did not have such a chance: the shells of their 47-mm cannons penetrated the American tanks only into the sides and stern.

The remnants of the 7th regiment (34 tanks out of 60 regular ones) retreated to the town of San Manuel. The Americans were in no hurry to catch up with them. Instead, they spent five days using bombs and shells to mix up Japanese positions with the ground. And only at dawn on January 26, the Shermans went on the attack again. From a safe distance, they shot at Japanese tanks one after another. By evening, the 7th Regiment was reduced to seven vehicles, the crews of which used a traditional Japanese technique to get out of a hopeless situation - a suicidal "banzai attack".

Destroyed Japanese Type 95 Ha-Go tank

In contrast, the commander of the 10th Japanese Tank Regiment, which found itself under attack from aircraft from American aircraft carriers, made a “European” decision: he ordered the soldiers to leave the tanks and fight their way to their own on foot.

The 6th Tank Regiment, which was located in the southern part of Luzon at the beginning of the landing, moved north and gained a foothold in the town of Muñoz. The regiment's soldiers had to repel the first attack on January 27. Having met resistance, the American infantrymen retreated, but their aircraft began a real hunt for Japanese tanks. The second attack, this time with the participation of Shermans, took place on January 30. As a result, the city was completely surrounded, and only 20 combat-ready vehicles remained in the Japanese regiment. Only a week later the encirclement received an order to retreat. At night, the Japanese who were still alive made a breakthrough through heavy American fire, in which only every fifth survived.

Company C of the 44th Tank Battalion operated against the Japanese in this battle. The 6th Army newspaper Tank News called the night battle "the hottest tank-versus-tank battle in the Pacific." During it, American soldiers not only had to shoot, but also clash with the Japanese in hand-to-hand combat. At dawn, the Sherman crews found 10 destroyed medium tanks, one light tank, a couple of trucks, an all-terrain vehicle and 245 killed Japanese in front of their positions. The battle cost Company C one killed, 11 wounded and two damaged tanks.

The last battle of Japanese tanks on Luzon took place in April 1945. The advancing Americans were approaching the headquarters of the Japanese 14th Army in Baguio City. The only tanks that General Yamashita had at that moment were three medium and two light vehicles from the 5th company of the 10th regiment. Since they had no chance of dealing with the Americans in open battle, Yamashita ordered a “suicide tank” attack, attaching explosive charges to the frontal armor of one medium and one light tank. According to the Japanese description, in this battle they managed to burn two Shermans, and the crews of the destroyed Japanese tanks, leaving the vehicles, rushed at the enemy, waving their swords.

Battle of Manila. American view

The American command knew that there were a large (by Pacific standards) number of Japanese tanks in the Philippines. Therefore, for backup, American units were reinforced not only by Sherman battalions, but also by battalions of M10 Wolverine tank destroyers. Looking ahead, we must admit that the Wolverines were superfluous: even the guns of conventional Shermans easily penetrated the weak armor of Japanese tanks.

American infantrymen, accompanied by an M10 tank destroyer, enter Manila

The report of the 640th Tank Destroyer Battalion contains evidence of how an armor-piercing shell pierced a Japanese tank right through and exploded in the mud about twenty meters from it. The anti-tank crews themselves, who fought on the M10, noted that Japanese armor was penetrated even by high-explosive shells, and at the same time much more destruction was caused inside the tank. So the vast majority of the shells that the Wolverines used were landmines. During the fighting in the Philippines, armor-piercing guns were used only a few times, when firing at pillboxes or caves. The losses of the self-propelled guns were also negligible: one M10 sank in the river, one was damaged by a mine, and several more self-propelled guns were slightly damaged by Japanese pole mines.

One of the priorities MacArthur gave his troops was the capture of Manila. The general believed that in this way it would be possible to reduce the number of casualties among civilians of the city and American prisoners of war, whom the Japanese held in the capital of the Philippines. In addition, the liberation of Manila was supposed to encourage the Filipinos to more actively fight against the Japanese invaders. Although over the past years they have already given local residents more than enough reasons to hate.

And here's what's interesting. As much as MacArthur wanted to take Manila as quickly as possible, Yamashita intended to surrender it as quickly as possible. The Japanese commander-in-chief considered the city a big trap, and its defense a waste of already meager forces. Maybe it would have turned out that way, but then one specifically Japanese aspect of military affairs intervened in the situation. In Japan, the navy has always looked down on the army. And the defense of Manila was led by Rear Admiral Iwabuchi Sanji, the former commander of the battleship Kirishima, sunk by the Americans in 1942. He decided that he must atone for the lost ship and achieve a death worthy of a samurai. To do this, it was necessary to defend the city, and not run through the mountains on the orders of “some army man.”

The Letran College building in the old city of Manila, riddled with American shells

Under the command of Iwabuchi, according to some sources, there were about 4,000 soldiers from lagging ground units and 15,000 poorly organized sailors who had no experience in ground combat. The rear admiral also had one tank - an American M3, captured by the Japanese during the capture of Manila in early January 1942. With these forces, Iwabuchi was determined to defend the city to the last Japanese, Filipino, or American, as it turned out.

At first, three American tank battalions (711th, 754th and 44th, which was already mentioned) and a battalion of tank destroyers took part directly in the battles for Manila. It was the “flying column” of tankers from the 44th battalion that managed to carry out MacArthur’s order and, quickly breaking through the Japanese, on the morning of February 3, reached the building of the Manila University of Santo Tomas, which held almost 4,000 prisoners of war.

American tank crews listen to the story of Bernard Herzog, released from captivity in Santo Tomas

Then the cleansing of the city itself began. The 37th American Infantry Division fought in the streets, supported by tanks from the 44th and 754th battalions. The history of the latter records:

«This became a new type of combat for both infantry and tanks. Tanks were used as mobile artillery in a very limited space."

Japanese mines brought a lot of trouble to the Americans. Despite all the efforts of the sappers, many tanks were blown up precisely on those streets that were “supposedly cleared” of mines.

On February 7, one of the American tank crews wrote in his diary: “Manila is burning!” Not only houses were burning, but also tanks - an attempt by two platoons of the 44th tank battalion to move forward ended tragically. The tanks were attacked by “20 mm and 5 inch naval guns, as well as grenade launchers with mines and Molotov cocktails.” Three tanks were burned, two more were damaged. Other units also reported suicide attacks with explosives and Molotov cocktails. Another tank received three 5-inch shells - the Sherman’s armor could no longer withstand such a caliber, the tank was completely destroyed, 4 tankers were killed.

In an attempt to protect Manila and its 800,000 civilian population, MacArthur "imposed severe restrictions on American artillery and air support." As in many other similar cases, this did not lead to anything good - when the battle for Manila ended, the city lay in ruins.

By February 13, the Americans had made their way to the Old City. Here the thick stone walls did not succumb to 75 mm shells. One of the buildings for which there were fierce battles for several days was the police station - it cost the 754th battalion three lost tanks. Another building memorable to tankers was the house known as “German” - when, after a long shelling, tanks and infantry tried to approach it, one tank hit a mine and was burned with Molotov cocktails.

Twice a trophy. In 1942, the Japanese took this M3 tank from the Americans. In 1945, the Americans recaptured it from the Japanese

The battle for Manila ended only on March 3, 1945. During the battle for the city, 1,010 American soldiers were killed and 5,565 were wounded. Japanese losses were about 16,000. About 100,000 Filipino civilians also died - both from “accidental” fire from both sides, and those killed by the Japanese during the so-called. "Manila massacre".

Material republished from the portal

worldoftanks.ru

as part of a partnership

Sources and literature:

- Rolling Thunder Against the Rising Sun: The Combat History of US Army Tank Battalions in the Pacific in World War II.

- Infantry's Armor, The: The US Army's Separate Tank Battalions in World War II.

- 640th TD Jan 9-Mar 1945 Operations Report.