The admiral's last flight

On the morning of April 18, 1943, 16 American P-38 Lightning fighters took off on a combat mission.

Over Bougainville Island they intercepted a pair of Japanese G4M Betty bombers escorted by six Zeros and shot down both bombers. This would have remained an ordinary episode if not for the passenger who died on one of the planes - the Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

Lockheed P-38G shoots down Betty with Yamamoto on board (photo source)

It was no coincidence that the fighters were there: thanks to the decoding of Japanese radio messages, the Americans knew about the time and route of the admiral’s inspection trip to forward bases in the Solomon Islands.

The decision to “get Yamamoto” was made at the very top, and the rest was a matter of technique.

The very next day the admiral's body was found at the site of the plane crash. The fact that, having received a 12.7-mm bullet in the head and breaking through the glazing of the lantern, he, dead, flew several tens of meters through the jungle and “continued to clutch his sword in his hand,” will be left to the conscience of Japanese propaganda. His ashes were taken to Tokyo, where a state funeral was held at the highest level.

The remains of the admiral's plane after the crash

Operation "Revenge" or the death of Admiral Yamamoto

On April 18, 1943, the US Air Force carried out an operation to kill Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy, who planned and organized the defeat of the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Our story will be about how this happened.

Biography and merits of Yamamoto

Isoroku Yamamoto was born on April 4, 1884 in the city of Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, into the family of an impoverished samurai. "Isoroku" in old Japanese means "56" - the age of the father at his birth. In 1916, Isoroku was adopted by the Yamamoto family and adopted this surname. After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1904, Yamamoto served on the cruiser Nisshin during the Russo-Japanese War. He was wounded in the Battle of Tsushima when a gun exploded, losing two fingers (index and middle) on his left hand, and also received multiple shrapnel wounds. Later, because of this injury, the geisha gave him the nickname “80 sen”, since they usually charged 100 sen for a manicure (10 for each finger). He graduated from the Naval Senior War College in 1914 and was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1916.

Yamamoto in 1905.

Politically, Yamamoto was a supporter of a peaceful solution to all conflicts at that time. He was strongly opposed to war with the United States, a position that stemmed from his studies at Harvard, his service as an assistant admiral, and his duties as a naval attaché in Washington. Yamamoto knew very well the economic potential of the United States and its military capabilities, which Japan could not compete with. He was promoted to the rank of captain in 1923, and in 1924, when he turned 40, changed his specialization from naval artillery to naval aviation. The first ship under his command was the cruiser Isuzu in 1923, and the next was the aircraft carrier Akagi. Yamamoto was a great supporter of the development of naval aviation. He did not support the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, nor the subsequent war with China, which began in 1937, nor the 1940 Berlin Pact with Hitler's Germany and Fascist Italy. As Under Secretary of the Navy, he apologized to United States Ambassador Joseph Clark Grew for the bombing of the gunboat Panay in December 1937. Yamamoto saw a great future for aircraft carriers, but did not have the opportunity to influence the ratio of battleships to aircraft carriers being built.

Captain Isoroku Yamamoto, Japanese naval attaché to the United States with US Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. 1925

Both Yamamoto's political and military positions made him a target for criticism by the Japanese militarists who effectively ruled the country at the time. However, on August 30, 1939, he was transferred from the Department of the Navy to the post of Commander-in-Chief of the United Fleet. On November 15, 1940, Yamamoto was promoted to the rank of full admiral. Despite Yamamoto's rejection in the highest political and military circles of Japan, he had unlimited popularity in the navy, where he always treated sailors and officers with respect. In addition, Yamamoto developed close ties to the family of the Emperor, who shared Yamamoto's respect for the West and considered him the most competent naval officer. Thus, Yamamoto remained in his high position, having practically no supporters either among politicians or among the military command of Japan. At the same time, it cannot be said that other political views and a vision of developing the navy in a different way indicated a lack of national patriotism or Yamamoto’s pacifism. It’s just that Yamamoto’s education and competence allowed him to see and analyze the situation more professionally than other government officials could do. He sought to prevent Japan from getting involved in the war not because of peace, but because of the weakness of the state’s military potential and the unpreparedness of the army and navy for large-scale hostilities at that time.

It is known from the admiral’s personal life that he spent a lot of time in the company of geishas, had success in gambling, but was known as a tough teetotaler. Due to the wounds he received, he had numerous scars, so out of embarrassment he visited the baths alone, usually at night.

Realizing the inevitability of war with the United States, Yamamoto believed that Japan’s only chance was to seize the initiative and inflict a series of heavy defeats on the Americans at the very beginning of the war, which could force American society to agree to a peace acceptable to Japan. Yamamoto planned a quick campaign, starting with the destruction of the US fleet at Pearl Harbor and simultaneously striking areas of Southeast Asia rich in oil and rubber, especially the Dutch East Indies, Borneo and British Malaya.

Although the admiral was best known for his work with aircraft carriers, mainly due to the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway, Yamamoto made even greater contributions to the development of coastal aviation, especially the development of the G3M and G4M medium bombers. His demands for greater flight range and the ability to arm aircraft with torpedoes arose due to Japanese plans to destroy the American fleet while it was moving across the Pacific Ocean. As a result, the required flight range for the bombers was achieved, although long-range escort fighters could not be built. The bombers were made to be lightweight, and with tanks full of fuel, they were especially defenseless against enemy fire (the tanks were metal, not fiber, and always caught fire when hit). For these qualities, the Americans nicknamed the G4M “flying lighter.” By the way, death will overtake Yamamoto in one of these planes.

Fleet Admiral Yamamoto. 1940

Yamamoto in 1941.

The raid on Pearl Harbor, which brought fame to Yamamoto, was, in his estimation, only partially a success. After two waves of attacks on the American naval base, the Japanese did not have sufficient firepower to develop the attack further. And the commander of the 1st Air Fleet, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, ordered a retreat, unable to use the favorable situation to locate and destroy American aircraft carriers that were absent in the harbor, or to continue bombing strategic targets on the island of Oahu. However, the American fleet stopped interfering with Japan's actions in the southwest direction for 6 months. At the political level, this attack ended in a complete fiasco for Japan, arousing the anger of the Americans and the desire to take revenge for the “cowardly attack.”

Having achieved the neutralization of most of the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto's Combined Fleet deployed to carry out the grand Japanese strategic plan developed by the Imperial Japanese Army and the Naval General Staff. The 1st Air Fleet continued to circle the Pacific, striking American, Australian, Dutch and British bases, from Wake Island to Australia and Ceylon in the Indian Ocean. The Japanese suppressed resistance from the remnants of American, British, Dutch and Australian naval forces in the Dutch East Indies through amphibious landings and several naval battles. They captured the “Southern Resource Zone” with its oil and rubber.

Having achieved its initial objectives with surprising speed and ease against an ill-prepared enemy, Japan paused to consider its next move. Yamamoto insisted on a “Decisive Battle” in which the remnants of the American fleet should be finished off, but the more conservative officers of the Navy General Staff did not want to take risks. In the middle of discussing the plans, Doolittle's air raid hit Tokyo and the surrounding areas, showing staff officers the capabilities of American aircraft carriers and the soundness of Yamamoto's plan. The General Staff agreed to the operation to capture Midway Atoll, accompanying the plan for the invasion of the Aleutian Islands.

And again, Yamamoto’s developed plan could not be fully implemented. Having captured the islands of Tulagi and Guadalcanal, the Japanese fleet was forced to retreat, encountering American aircraft carriers in the Coral Sea. While preparing for the invasion of Midway, the Japanese lost sight of American aircraft carriers. Yamamoto's fleet had a threefold numerical superiority over the American one, and the admiral had no doubt of success. However, American cryptanalysts were able to decipher the Japanese military code, and American Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, managed to outmaneuver Yamamoto, placing his smaller force in an ambush and defeating the Japanese fleet piece by piece. This defeat of Yamamoto became one of the main turning points in the history of World War II in the Timhawkian theater of operations. After the loss of four aircraft carriers, many aircraft and a huge number of experienced sailors and pilots, the Japanese fleet lost the initiative, it could no longer support offensive operations with the same strength, and the war for Japan in the Pacific turned from offensive to defensive.

Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. 1942

Admiral Yamamoto in full dress uniform. 1942

Admiral Yamamoto was left in his position only in order to somehow support the undermined morale of the United Fleet. Yamamoto carried out several small operations using the Combined Fleet that caused great damage to the enemy, but he himself was badly battered and was no longer able to lead the Americans into a large open battle. The losses of destroyers in transport operations of the Tokyo Express were especially severe. Yamamoto shifted the role of air support from battered aircraft carriers to coastal aviation.

Operation Revenge

To boost the morale of the troops after the defeat at Guadalcanal, Yamamoto decided to personally inspect the South Pacific troops. On April 14, 1943, as part of an American intelligence operation codenamed "Magic", a radio transmission was intercepted and decrypted, which contained specific details about Yamamoto's departure, including the schedule of arrival at all sites, as well as the numbers and type of aircraft on which he and his escorts will move around. It was clear from the encryption that Yamamoto would fly from Rabaul to Ballalae airfield on Bougainville Island in the Solomon Islands on the morning of April 18, 1943. There is an opinion that US President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to “get Yamamoto”, but no documents have yet been identified in this regard. Knox conveyed the president's wishes to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who authorized an operation on April 17 with the task of intercepting and shooting down Yamamoto's plane.

The 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, 13th Air Force, was chosen to conduct the interception because their P-38 Lightnings had sufficient range. To increase motivation during the mission, the pilots were notified that they would be intercepting Admiral Yamamoto's aircraft. The command decided to intercept the Japanese admiral in the air, since in this case he had less chance of escape. According to the order, no one could leave the battle until the target was destroyed. Also, in case of a crash, each pilot was given an impressive amount of money to settle accounts with the local friendly population.

Admiral Yamamoto greets Japanese naval pilots in Rabaul hours before his death.

Colorized photograph of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, hours before his death, inspecting fighter jets at Rabaul Air Base.

On the morning of April 18, 1943, despite advice from local commanders to cancel the flight for fear that the plane would be ambushed, Yamamoto took off from Rabaul on schedule in a Betty bomber (Yamamoto was seated in the control room to the pilot's left) for the 315-mile flight. It is possible that Yamamoto flew on the plane on purpose in order to, by dying, relieve himself of responsibility and shame for the defeat of Japan, which by that time was already looming. The other bomber housed his staff officers. They were covered by six Zero fighters.

Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber.

P-38G Lightning fighter in flight.

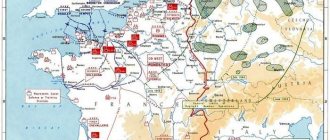

Movement diagram of the Americans (green) and Japanese (red) on April 18, 1943.

Shortly thereafter, 18 specially equipped P-38s with extra fuel tanks took off from Guadalcanal (one failed to take off, one returned due to breakdown, two more crashed into the sea). The squadron commander's aircraft was additionally equipped with a naval compass to increase target accuracy. They flew at very low altitude to avoid detection by enemy radar, and maintained radio silence for almost the entire 430-mile flight. At 09:34 Tokyo time, the groups met in the south of Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville, and a dogfight ensued between 14 P-38s (at least two failed to drop additional tanks before attacking and at least two others were forced to cover them, so that the number the American superiority was not overwhelming) and six Zero fighters from Yamamoto’s escort group.

Painting by artist Ron Cole “Ambush on Yamamoto.”

Lieutenant Rex T. Barber attacked the first of two Japanese bombers, which was Yamamoto's plane. He showered the plane with fire from a cannon and machine guns until the left engine of the bomber began to smoke. Barber turned to attack the second bomber; At that moment, Yamamoto's plane crashed into the jungle. After the battle, another pilot, Captain Thomas George Lanphier, tried to prove that he was the one who shot down the main bomber. This statement began a dispute that lasted for several decades until a special expedition analyzed the direction of the bullets at the crash site. Most historians nowadays attribute Yamamoto's plane to Barber. The second bomber was hit and made an emergency landing on the water, where several officers survived.

Only one American pilot, Lieutenant Raymond K. Hine, was killed in this battle. His plane did not return to base after it was shot down by Imperial Japanese Navy Air Group 504 pilot Shoichi Sugita. Considering that the fighters had to fight at the limit of their range, even with additional fuel tanks, the downed pilot had no chance of returning. No Japanese fighters were damaged.

After operation

A Japanese rescue party under the command of Army engineer Lieutenant Hamasuna found the crash site and Admiral Yamamoto's body the next day in the jungle north of the former Australian coastal outpost of Buin. According to Hamasuna, Yamamoto was thrown from the plane's fuselage under a tree, his body sitting upright, strapped to his seat, and a white-gloved hand gripping the hilt of his katana. Hamasuna said it was fairly easy to identify Yamamoto, with his head tilted as if he was thinking. An autopsy revealed that Yamamoto suffered two bullet wounds, one to the back of his left shoulder and the other to the lower part of his lower jaw, with an exit wound above his right eye. A Japanese naval doctor who examined Yamamoto's body determined that Yamamoto died from a head wound. Despite this, whether the admiral survived the crash has become a matter of debate in Japan.

The wreckage of the G4M aircraft on which Admiral Yamamoto died.

It was the longest air interdiction operation in the history of the war. In Japan it became known as "Naval Incident A". The death of the admiral dealt a huge blow to the morale of the Japanese troops and shocked Japan, which officially recognized the incident only on May 21, 1943. The advert said that in April, while directing strategy on the front line, the admiral "engaged the enemy and met a gallant death in a military aircraft." To avoid informing the Japanese that their code had been deciphered, American newspapers reported that civilian observers had seen Yamamoto board a plane in the Solomon Islands. The names of the American pilots were also not published - the brother of one of them was in Japanese captivity, and they feared for his safety. The truth about the operation was published only on September 10, 1945 in the Associated Press newspaper, whose correspondent prepared a detailed report on May 10, but military censorship did not allow the material to be published.

State funeral of Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto on June 5, 1943.

Captain Watanabe and his entourage cremated Yamamoto's remains at Buin, and the ashes were returned to Tokyo aboard the battleship Musashi, Yamamoto's last flagship. Yamamoto was given an honorable burial on June 3, 1943, and received the title of Marshal of the Fleet and the Order of the Chrysanthemum, First Class, posthumously. The German government also awarded him the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. Some of his ashes were buried in the general cemetery in Tama and the rest in his ancient family cemetery at Chuko-ji Temple in Nagaoka.

Isoroku Yamamoto's grave at Tama Cemetery.

Yamamoto Isoroku Memorial Museum in Nagaoka today.

The wreckage of Admiral Yamamoto's plane is in the jungle today.

The remains of Yamamoto's plane still lie in the jungle about 9 miles from the city of Panguna. The crash site is about an hour's walk from the nearest road. Although the wreckage of the plane was carefully "cleaned up" by souvenir hunters, parts of the fuselage remained where it crashed. The site is located on private land. Previously, access was difficult as land ownership was disputed. However, since 2015, visitors can access the site by prior arrangement.

Museum exhibition depicting the crash site of Yamamoto's plane.

Part of one wing was removed and is on permanent display at the Isoroku Yamamoto Family Museum in Nagaoka, Japan. One of the plane's doors is in the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery.

In conclusion, we note that Operation “Revenge” can be classified as exemplary, both at the highest command level and at the planning and execution stage, which did not happen so often for the Americans.

Based on materials from the sites: https://en.wikipedia.org; https://www.japantimes.co.jp; https://eadaily.com; https://ru.wikipedia.org; https://warspot.ru; https://warhead.su; https://www.airwar.ru; https://naspravdi.info; https://www.historynet.com; https://www.history.navy.mil; https://www.donhollway.com.

All site publications

Share in:

Life after death

Japanese admirals of World War II died in different ways. Chuichi Nagumo, blamed for the failure at Midway and “indecisiveness” at Pearl Harbor, committed suicide in 1944 while defending the island of Saipan. Another of Yamamoto’s subordinates, his chief of staff Matome Ugaki, after the announcement of surrender, boarded a kamikaze plane that he himself had invented. And the head of the General Staff of the Navy, Osami Nagano, died in prison without waiting for the verdict of the Tokyo Tribunal.

If Yamamoto had remained alive, he would have been guaranteed a verdict from the same tribunal. And it is unlikely that the “author of Pearl Harbor” would have gotten off as easily as the Minister of the Navy, Admiral Shigetaro Shimada, who served ten years of his life sentence. However, Yamamoto was lucky to die in time, and he remained in history in a completely different capacity.

The heroic death of an admiral in the 2011 Japanese film Isoroku

Not only in most historical works, but also in popular culture - from books and films, to comics and anime in the "alternative history" genre - the commander-in-chief of the United Fleet is depicted exclusively "all in white." And this concerns not only Japan, but also, oddly enough, their opponents in World War II.

As a result, in the public consciousness, Isoroku Yamamoto appears as a fan of America, an opponent of war, and almost a pacifist. The creator of Japanese carrier-based aviation and a great naval strategist who led Japan from victory to victory. Allegedly, it was not even the overwhelming superiority of the United States that stopped him, but more the annoying accidents that constantly undermined his subordinates and his superiors who did not appreciate his genius.

Portrait of the "sea god"

The future admiral was born on April 4, 1884. It is noteworthy that the name Isoroku is translated from Old Japanese as the number “56”. This is exactly how old Father Isorok was at the time of his son’s birth. Isoroku's childhood occurred during the so-called Meiji Revolution - a time of active capitalization of the Land of the Rising Sun, when rice fields were replaced by factories and railways, and squads of medieval samurai turned into the officer corps of the army and navy. There were no vacancies in the ground forces, so Isorok had to choose ships... In 1904, he graduated from the Naval Academy and immediately landed on the front line of the Russo-Japanese War. In the Battle of Tsushima, a young lieutenant of the Japanese fleet lost two fingers on his left hand. Thus began Yamamoto’s career, which by the beginning of World War II led him to the post of Commander-in-Chief of the Navy of the Japanese Empire. Note that among the Japanese high command, Isoroku turned out to be a black sheep. Not to the detriment of the ship's service itself, the tireless Yamamoto managed to graduate from Harvard University and twice visit the naval attache to the United States. Not only that, but contrary to the prevailing opinion in the maritime environment, Yamamoto saw the main strength of the fleet not in giant battleships, but in aircraft carriers. To complete the portrait of this non-trivial personality, we add that Isoroku was extremely passionate. He loved poker, bridge and billiards. He often said: “If I opened my own casino in Monaco, I would bring much more benefit to the emperor than in my current post!” And at the same time he clearly realized that it was impossible for Japan to win the war against the United States. But he was a military man. In the army, as you know, orders are not discussed, but rather carried out. Having received an order from the imperial headquarters to deliver a powerful blow to the United States, Yamamoto obeyed and carried it out in an exemplary manner. In the first months of the war, the American fleet was paralyzed. The Japanese had captured most of Indochina, the Pacific Islands, and were already setting their sights on Australia. President Roosevelt called the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor “American day of shame.” Japanese newspapers enthusiastically referred to Yamamoto as the “evil rock of the Yankees” and the “sea god.”

The real Yamamoto

In reality, Isoroku Yamamoto was a career officer who rose to the highest rank. There are no such people as pacifists. He was indeed opposed to both the alliance with Germany and Italy and the new expansion - but solely because he considered it untimely until America was seriously bogged down in the European war.

Yamamoto, of course, recognized the capabilities of the United States. But he, like any normal Japanese nationalist, never suffered from “love” for the country that held back his homeland in East Asia. So, after making a political decision, Yamamoto became one of the most active proponents of the idea of preventive neutralization of American forces in the Pacific Ocean as the first and main condition for the successful implementation of Japanese plans.

Isoroku Yamamoto greets Japanese pilots a few hours before his death

Admiral Yamamoto was, without a doubt, a charismatic leader and an excellent organizer, but it is also not worth attributing to him an exceptional role in the creation of the “air sword of the empire.” Here it is enough to remember that the main Japanese know-how in the field of carrier-based aircraft - its massive use - as well as the creation of the world's first aircraft carrier formation, the 1st Air Fleet, were invented and promoted by completely different people.

Rochfort comes into play

If the passionate and talented Yamamoto became an evil fate for America, then among the Americans, in turn, the “evil fate Isoroku” was found. It was Captain 2nd Rank Joseph Rochfort. A mathematician and analyst, he led the top-secret Haifo station, which was engaged in radio interception and decryption of Japanese messages. Rochfort managed the unthinkable. He and his staff cracked the Japanese Navy's top secret radio code, which allowed the Yankees to read almost all radio messages at the same moment that the Japanese themselves received them. It was so incredible that the American command... simply refused to believe the data from “Haifo”! Everything changed only after June 1942, when the commander of the American fleet, literally pressed to the wall by a continuous series of Japanese victories, out of despair, decided to plan his actions based on Rochfort’s messages. As a result, the battle for Midway Atoll ended, in the words of the Americans themselves, with an “accidental victory.” Yamamoto lost four of his best aircraft carriers and hundreds of aircraft with the most experienced pilots. For Japan, this was an irreparable loss. The war has reached a turning point...