Germany has good engineering and industry. Together they created many useful and efficient machines and equipment. In the event of war, their symbiosis was dangerous for a potential enemy - the USSR felt this firsthand during the Great Patriotic War. But there were some “punctures”.

Some monsters of the German military industry were scary on paper and to the eye, but the practical result of their use tended to zero. Among these “scarecrows” is the battleship Tirpitz. The British feared him not because he caused them significant damage, but because he simply existed.

What will you name the yacht... It is clear that the German sailors did not know this song by Captain Vrungel. Otherwise they would have chosen a different name for the super battleship. And so the history of the ship was quite consistent with the history of the man whose name it received.

Father of the German Navy

Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz enjoyed a good reputation among German sailors. He was extolled for a specific biographical fact: he did not lose a single battle. There is a good reason for this - he did not participate in any of them.

But the admiral had merit. Before the First World War, he actively advocated the development and strengthening of the German fleet. The goal was to end English dominance at sea. Tirpitz liked large ships with thick armor - he believed that these floating tanks would defeat the British.

The result turned out to be so-so - the British were more experienced in maritime affairs, and for every German ship they built 2 of their own.

Submarine warfare, of which Tirpitz was a fan, also did not succeed. It only made the United States, outraged by the underwater attack on the Lusitania, become Germany’s opponents (this passenger liner sank after being torpedoed by the U-20 submarine. 1,198 people died).

But in the minds of the German military, Tirpitz remained the “father of the fleet” and a symbol of the impending victory over England on the water. So his name was used to title the new ship.

Chancellor and Admiral

In 1935, the military ordered two battleships for construction. Hitler, having come to power, immediately began to ignore the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, which limited the German military potential, and this turned out to be an issue on which the Germans were really at one with him (the conditions set by the victors were too humiliating).

It was decided to build ships in the country capable of replacing the British dreadnoughts. One of them was named “Bismarck”, and the second was given the honor of becoming “Tirpitz”.

There was something wrong with them from the beginning. The battleship Bismarck set out on the only voyage in her life, and the British sank her (not without damage to themselves, but still).

Tirpitz survived until 1944, but its combat effectiveness turned out to be insignificant. The main occupation of the battleship was... playing hide and seek with the British military. The ship repeated the fate of the admiral - he did not have the chance to take part in a single notable battle.

Description

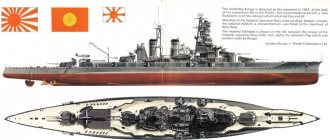

The battleship Tirpitz had a maximum displacement of 53,500 tons, a total length of 253.6 meters and a width of 36 meters. The ship was perfectly protected: the armor belt covered 70% of its length. The armor thickness ranged from 170 to 320 mm, the wheelhouse and main caliber turrets had even more serious protection - 360 mm.

Each main caliber tower had its own name. In addition, it should be noted the excellent fire control system for naval artillery, excellent German optics and excellent training of the gunners. Tirpitz guns could hit 350 mm armor at a distance of up to twenty kilometers.

The Tirpitz's armament consisted of eight main-caliber guns (380 mm), located in four turrets (two bow and two stern), twelve 150 mm guns and sixteen 105 mm cannons. The ship's anti-aircraft armament, consisting of 37 mm and 20 mm guns, was also very powerful. Tirpitz also had its own aircraft: on board there were four Arado Ar196A-3 aircraft and a catapult to launch them.

The ship's power plant consisted of twelve Wagner steam boilers and three Brown Boveri & Cie turbines. It developed a power of more than 163 thousand hp. s., which allowed the ship to have a speed above 30 knots.

The Tirpitz's cruising range (at a speed of 19 knots) was 8,870 nautical miles.

Summarizing all of the above, we can conclude that the Tirpitz could withstand any Allied ship and posed a serious threat to them. The only problem was that the number of pennants in the American and English fleets was much greater than in the German ones, and the tactics of warfare at sea exclude one-on-one knightly duels.

The British were afraid of German battleships and closely monitored their movements. After the battleship Bismarck went to sea in the spring of 1941, the main forces of the British fleet were sent to intercept it and the British eventually managed to sink it, although this cost them the loss of the first-class battleship Hood.

Giant Transport Hunter

It is known that Hitler was characterized by gigantomania when it came to weapons. He was fascinated by large and scary-looking devices. In fact, the giants did not justify the resources spent on their construction (for example, the giant Dora cannon, which was never able to properly fire at the 30th Sevastopol battery).

The same thing happened with Bismarck and Tirpitz. But the characteristics of the ships commanded respect. The battleships with the best performance (the same Japanese Yamato) took part in the war, but the German ships were also a considerable force.

Postscript system in German

It (the system) accompanied the ship already at the design stage. But it was the opposite of what was used by Soviet bureaucrats.

To please the requirements of the Treaty of Versailles, which limited German military potential, the data on ships was not overestimated, but underestimated.

Thus, the officially declared displacement of the Tirpitz was supposed to be 35 thousand tons. But already in the project “for internal use” the figure of 45.5 thousand tons appeared. Further, the battleship's displacement was further increased during reconstruction (up to 53 thousand tons), but no one hid this anymore - the war had begun.

A similar miracle happened with the Tirpitz’s armament - officially the main caliber was supposed to be 350 mm, but for some reason in reality it turned out to be 380 mm.

Design and construction

After coming to power, the Nazis began to restore the former power of the German navy. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was prohibited from launching ships with a displacement of more than 10 thousand tons. This led to the creation of so-called pocket battleships - ships with a small displacement (about 10 thousand tons) and powerful weapons (280 mm caliber guns).

It was clear that his main rival in the upcoming war would be the British Navy. A discussion arose in the German military department about which ships are better to build in order to successfully conduct combat operations on enemy communications: underwater or surface.

In the mid-30s, a secret plan Z was adopted, according to which the German fleet was to be significantly replenished within 10-15 years and become one of the strongest on the planet. This program was never implemented, but the battleships provided for by the plan were nevertheless launched.

The battleship Tirpitz was laid down on November 2, 1936 at the shipyard in Wilhelmshaven (Bismarck was laid down on July 1). According to the original design, the ship was supposed to have a displacement of 35 thousand tons, but in 1935 Germany refused to comply with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, and the tonnage of the battleship was increased to 42 thousand tons. It received its name in honor of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, an outstanding naval commander and the actual creator of the German Navy.

The ship was originally conceived as a raider - with high speed and a significant cruising range, the Tirpitz was supposed to work on English communications, destroying transport ships.

In January 1941, a crew was formed, then testing of the ship began in the eastern Baltic. The battleship was declared fit for further operation .

Technologically advanced scarecrow

The Tirpitz was launched in 1939, and immediately completed its first task - the British were scared. They had the habit of keeping 2 of their own in reserve of a similar class against each German ship (in war there is no time for a dueling code). Battleships were needed against a battleship. But the British lacked confidence that they had such a reserve against Tirpitz and Bismarck.

The battleships of the “King George” series were not the best, but then the Germans presented a really powerful battleship. The German battleship Tirpitz was not perfect, but its power was impressive.

The tactical and technical characteristics (linear, armor, running, fire) of the Tirpitz were not record-breaking, but good. Here you can simply refer to the numbers.

- Dimensions - 253.6 m total length, 15 m total height (from the keel), 36 meters wide.

- The thickness of the armor is from 145 to 320 mm, on the main caliber turrets and wheelhouse - 360 mm.

- Maximum speed is more than 30 knots.

- Main caliber – 380 mm (8 guns); plus another 12 150 mm cannons and 116 anti-aircraft guns of various calibers.

- Autonomous cruising range is up to 16,500 km.

- Deck-based aviation - Arado aircraft 4 pcs.

The ship was propelled by 12 boilers and 3 turbines. It had a radar station and, in addition to artillery, carried torpedo tubes. During its operation it was modernized several times; in particular, the number of anti-aircraft installations increased.

But at the same time, the Tirpitz was initially planned to be used not for battles with an equal enemy, but for hunting transport ships. The Nazis' focus was on English maritime trade, and they wanted to stop it. The ship was to be used not as a battleship, but as a cruiser.

So they sent him to the North Sea - it was safer, and the spoils were at hand (transport convoys carrying equipment, weapons and materials under Lend-Lease to the northern ports of the USSR).

The clear superiority of the British in the west and the fate of the Bismarck forced the Nazi command to save the second naval miracle.

The battleship was prepared for a pleasant sinecure - to chatter with Arctic convoys. The command was afraid that something unexpected would happen to the Fuhrer’s favorite naval toy. And put her out of harm's way.

Father of the German Navy. Who is he, Alfred Tirpitz?

On March 19, 1849, Alfred Tirpitz, a man known mainly as the creator of the German navy, was born in the town of Küstrin in Prussia. Meanwhile, Tirpitz is famous not only for the fact that, having become the naval secretary of state at the end of the 19th century, he managed to shake the power of the mistress of the seas, Great Britain, even before the outbreak of the First World War. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia describes Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz as follows: “played a large role in determining the aggressive political course of Germany”; “expressing the interests of the German militarists, he acted as an ideologist of the naval arms race”, “for an alliance with Japan and the neutralization of Russia”; “After the war he took revanchist positions.” Considering that TSB was published in millions of copies from 1926 to 1990, it is sad to realize how many people were misled about this person. In the memoirs of Tirpitz himself, which today can easily be found at least on the Internet, he does not appear as an aggressor. And he doesn’t express anyone’s interests except, let’s say, the interests of his own heart and mind. His thoughts are permeated with pain for the Germans, who did not deserve, in his words, a humiliating capitulation. “The German people did not understand the meaning of the sea,” writes the Grand Admiral. “At his fateful hour, he did not use his fleet. Now I can only erect a tombstone for this fleet. In its rapid ascent to world power and its even more rapid fall, caused by the temporary insignificance of its policies and the lack of national feeling, the German people experienced a tragedy the likes of which history knows not." Against the background of age-old German traditions, Tirpitz’s plans to create a navy looked like an absolute utopia. In some ways, Tirpitz resembles Henry Ford: both opened hobos production from scratch, which they provided with everything necessary. Both had a passion for invention and innovation. In the case of Tirpitz, this is a torpedo business. Having become the commander of a destroyer flotilla in 1878, with his own hands, working as a tinsmith, he improved the self-propelled torpedo of the English engineer Robert Whitehead and achieved hit accuracy unattainable for the British and the ability to hit a target at a distance of 400 meters, and later 12 kilometers. By the end of the 80s of the 19th century, he was known not only in government and maritime circles, but also among large industrialists. Believing that the security of the empire rested on a powerful navy, Tirpitz understood that his country, forced to maintain a huge land army, could not keep up with Great Britain in the number of ships. Fearing exclusively England, Tirpitz clearly sympathized with Russia and considered it a natural ally, as evidenced by these lines: “In the future, I would not see any threat to us even if the Russian Empire again achieved its former power. I don’t know if there is an example in history of greater blindness than the mutual extermination of Russians and Germans to the greater glorification of the Anglo-Saxons.” Tirpitz considered the highest merit of warships to be their survivability and ability to continue fighting despite serious damage. The best grades of armor steel were installed on the German Moltke-class battlecruisers and Nassau-class dreadnoughts. Their speed also turned out to be an unpleasant surprise for the British. In his memoirs, Tirpitz quotes an article in the London weekly The Saturday Review, published in 1897. The author clearly looked at the root. In this programmatic and visionary material, as in an ominous mirror, a glimpse of the coming catastrophe was glimpsed: “Bismarck has long recognized, and the English people are beginning to understand this, that in Europe there are two great, irreconcilable, antagonistic forces, two great nations that are turning into their possession of the whole world and want to demand trade tribute from it. England... and Germany... the German traveling salesman and the English traveling merchant compete in every corner of the planet, a million small clashes creating the pretext for the greatest war that mankind has ever seen. If Germany were wiped off the face of the earth tomorrow, then the day after tomorrow there would not be an Englishman in the whole world who would not be richer for it.” “Forge of Germanism” At the turn of the century, Great Britain had 38 squadron battleships of the 1st class and 34 armored cruisers, and Germany, respectively, only seven and two. In 1898, the latter adopted the law on the fleet prepared by Tirpitz, which provided, in particular, for the construction of 19 new squadron battleships by 1917. Two years later, the Secretary of State obtained consent from the Reichstag to double the number of battleships, that is, to 38. About England, Tirpitz wrote: “The construction of the fleet there is successful because the properties of the nation and the great historical traditions have created a solid foundation for this.” There was nothing like this in his homeland. Most Prussian nobles, by their upbringing and worldview, were not suitable for such professions as, say, a naval engineer. Naval officers for the most part belonged to the “third estate.” Many admirals and naval commanders of the Kaiser's Reich, including Tirpitz, the son of a poor burgher, received the prefix “von” to their surname only after many years of service. By the beginning of the First World War, the officer corps of the German army numbered 30 thousand people. The fleet had 2,500 officers. Relatively few, but in 1897, when Tirpitz headed the naval department, there were about 250 of them. Under Tirpitz, naval personnel were replenished not only by the coastal population, fishermen, merchant seamen, but also by residents of the inland provinces of Germany, including the Alsatians: service in the then large ships no longer required such professional qualities as in the days of sailing ships. “We were the only imperial institution,” argued the Secretary of State, “which opened wide horizons of cooperation to hundreds of thousands of people. The fleet became the forge of Germanism.” Tirpitz was an excellent geopolitician and strategist, he clearly understood the realities of the then world and the balance of power. Based on the sum of factors, he put forward his “risk theory”: Germany, in his opinion, should have such a powerful fleet that London would have to avoid any kind of conflict with Berlin. However, with all the undoubted strategic advantages of the “risk theory,” it had one weak point: sea power does not arise overnight, but requires a long period of painstaking creation. Could Britain afford such a luxury to a mortal enemy? But the Germans had no choice. The point was, as Tirpitz wrote, “to preserve the economic prosperity of our country, to save our ancestral lands along the Rhine from decline, our Hanseatic cities from becoming simple English trading posts, and our entire national body from the strangulation prepared for England to him." Tirpitz knew what he was getting into. For years, as chief of the naval staff and then secretary of state, he prepared his country for this test. On his initiative, publishers, artists and writers were involved in popularizing the fleet. A naval magazine began to be published; Schoolchildren were given awards for essays on maritime topics. In the meantime, public opinion was being prepared, state-owned shipyards were transformed from “simple tin workshops” into well-equipped enterprises, workers were trained, research was conducted on unsinkability and armoring of ships, and on improving artillery. The Secretary of State placed the main emphasis on the technical superiority of German ships over English ones. “Since there are no terrain conditions at sea, and bypassing the flanks, etc. plays a much smaller role than on land, Tirpitz noted, then numerical superiority does not have the same importance here as “the largest battalions on land.” In his work, Tirpitz sought to try all the new items in shipbuilding and military equipment. He considered the highest advantage of the ship to be the ability to maintain stability in the vertical plane and continue the battle despite critical damage. Such was the Nassau, the first of a series of German dreadnoughts, laid down in July 1906 at the Imperial shipyard in Wilhelmshaven. The thickness of the main armor belt of the Nassau, which reached the upper deck, was 306 millimeters - versus 229 for the dreadnoughts of the British Royal Navy. German 280-mm shells penetrated thin British armor from a much shorter distance than English 305-mm shells penetrated German armor. Tirpitz remained faithful to the principle of survivability when designing battlecruisers of the Von der Tann and Moltke type: they were equipped with the best grades of armor steel and solid watertight bulkheads below the waterline, and the most advantageous methods of armor placement were used. The speed of these ships was an unpleasant surprise for the British. Thus, the battle cruiser Derflinger, which entered service in 1914, produced more than 28 knots instead of 26.5, which were indicated in official reference books. The Germans, compared to the enemy, not only created more advanced optics, sights, charges and shells, they trained their artillerymen well. For example, they took only three minutes to shoot, while the British needed twice as much time. In addition, if five hits from German shells were enough to send an English battlecruiser of the Invincible class to the bottom, then German ships such as the Derflinger could stay afloat and reach their base even after 15-20 hits. Submarine warfare In parallel with the construction of the fleet, Alfred von Tirpitz solved a lot of infrastructure problems, such as the need to expand locks and canals. “The length and size of the ships were limited by the Wilhelmshaven locks,” the grand admiral notes in his memoirs. “These two circumstances contributed to the fact that ships built after the adoption of the first shipbuilding program could not reach speeds that corresponded to the power of their machines. This difficulty became chronic and was eliminated in 1910 when a third lock was built in Wilhelmshaven. A big obstacle, absent among other seafaring nations, was the presence of sand banks at the mouths of our rivers flowing into the North Sea: they prevented the ships from giving the ships an appropriate draft. In a certain sense, we were limited by the same factors that in the 17th century cost the Dutch so dearly in their struggle with the British.” Tirpitz, as one of the top officials of the empire, had to constantly maneuver between the demands of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the leaders of the cabinet. Usually he was not informed about those foreign policy steps that could be perceived as a challenge to London or other capitals. Both diplomats and the impulsive Kaiser made public statements against Germany's obvious and hypothetical opponents in an aggressive tone. Tirpitz's principles - to avoid incidents that offended the British - were violated all the time. The activity of German submarines in the waters surrounding Britain and Ireland led to the opposite effect for Berlin. The death of the Lusitania liner caused a sharp reaction in the United States and is believed to have become the pretext for this country's entry into the First World War. To reassure Britain, which was concerned about the growing German naval power, the Secretary of State was ready to consolidate the numerical dominance of the English fleet over the German one in the ratio of 16 to 10, which Churchill proposed. The parties entered into a corresponding agreement in 1913. And when the fateful days of July 1914 arrived, Tirpitz proposed to act extremely decisively. He saw the main ways of putting pressure on the British in the capture of the coast near Calais and Flanders and in a naval battle. In Germany, the memory of Tirpitz was immortalized not only in medals. The battleship of Hitler's Reich, launched in 1939, received his name. With its presence in Norway, this ship threatened Arctic convoys. “Every sailor realized at the beginning of the war,” the grand admiral wrote, meaning himself, “that he would have to deal with an enemy whose invincibility at sea had become a dogma. The French, Russians, Italians were not taken into account as opponents at all.” Army and government officials considered actions at sea to be of secondary importance, and for the perspicacious Tirpitz this was the whole tragedy of the situation. He unsuccessfully called for initiative and to take advantage of the fact that the British did not know about the qualitative superiority of German ships. The Kaiser demanded that losses be avoided and that all departures to sea by large forces be coordinated with him. So did Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, commander of the High Seas Fleet, as the main fleet of the German Kaiser's Navy, based in Wilhelmshaven, was called. “The fleet could have fulfilled its task if it had been used correctly,” Tirpitz later asserted. “The organization, training, mentality and spirit of our fleet were aimed at rapid action and attack in the same way as the German land army was aimed at maneuver warfare. Our best chance was to fight. The longer the war dragged on, the more definitely the British avoided a collision with him.” But the Germans, or more precisely, their General Naval Headquarters - Genmor, also avoided the same thing. Britain was aware that Germany had put an end to its undivided dominion over the waters. Moreover, German sailors were close to an even more impressive success. Here is what the London daily Morning Post wrote on May 18, 1918: “If, a week before the outbreak of war, Germany had distributed her powerful cruising fleet along remote sea routes, it might have destroyed us, or, in any case, would have caused very heavy losses. Later, the German command delayed the naval battle for so long that it was too late for this. Further, Germany tried to achieve the goal to which the naval battle did not lead it, with the help of submarine warfare. This was the greatest danger our country has ever faced." Tirpitz initiated the submarine war. At the same time, he categorically opposed the blockade of the coast of England, the issue of which Genmore discussed. The Secretary of State said that since Germany does not yet have a sufficient fleet of submarines, it should start small - with a blockade of the Thames mouth. In February 1915, Genmore did his own thing: he declared the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, a dangerous zone for commercial shipping, which caused discontent in many countries. And after the German U-20 torpedoed and sank the British passenger liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland on May 7, 1915, protests from the United States forced the Germans to sharply reduce the activity of their submarine forces in the area. Considering unrestricted submarine warfare the only opportunity to reverse the unfavorable situation on the fronts as a whole, Tirpitz did not deviate from this strategy. But since the Kaiser rejected her, the Grand Admiral, supported by no one, turned to Wilhelm II with a request for resignation, which he received on March 17, 1916. Meanwhile, even with limited submarine warfare, one voyage of a German submarine accounted for 17 thousand tons of sunk ships. It was not destined to bring the figure to 51 thousand tons, as Tirpitz expected. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1917, the total losses of the English fleet in tonnage were so great that they brought the country to the brink of disaster. But in the end, the victory in World War I, despite the titanic efforts of Alfred von Tirpitz, was celebrated in London, not in Berlin. The Germans should thank Tirpitz for the fact that he not only overcame Germany’s mental and practical alienation from the sea, but also made it a maritime power. Read in full: https://news.day.az/unusual/477536.html

Headings: Genealogy, Origin of surnames, Biography, Interesting

Source:

https://news.day.az/unusual/477536.html

Captains and maritime law

It remains to be mentioned about the people who were supposed to set the floating miracle in motion. The battleship's crew in its best days consisted of 2,608 people, including 108 officers.

There were several changes in commanders on the Tirpitz during the ship’s existence, but all of them were at the rank of captain zur see (according to the Russian system, captains of the 1st rank). F.K. Topp was the first to receive the battleship in February 1941 (before that he had managed the construction and testing of the ship).

The fate of the last commander deserves attention. Robert Weber knew the unwritten law of the sea well. He did not leave his ship, and together with the Tirpitz went to the bottom. 1,700 crew members died with him; part of the crew managed to escape.

Terrible and vulnerable

In May 1941, the battleship Bismarck, together with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, set out to paralyze British shipping in the North Atlantic. On May 24, the Bismarck destroyed the British battlecruiser Hood in a battle in the Denmark Strait.

As a result of the retaliatory actions of the British fleet, the Bismarck was damaged by air strikes, after which it was finished off by surface ships. The battleship sank on May 27, 1941.

After the death of the Bismarck, the Kriegsmarine command began to be extremely careful about the use of the Tirpitz.

In January 1942, the battleship was transferred to Trondheim, Norway, from where it was to threaten northern convoys heading to the Soviet Union.

The Tirpitz went to sea infrequently, but its mere presence forced the British admirals to adjust their plans. Fearing the German giant, the Allies tried with all their might to send him to the bottom.

The sinking of the cruiser Hood. In the foreground is a model of the battleship Bismarck. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org/ Ericknavas

Symbolic thunderstorm of Arctic convoys

Since January 1942, the Tirpitz served in the North Sea. In the Norwegian fjords one could find a convenient anchorage for a battleship, hardly noticeable to the enemy. The German command wanted to protect the only remaining newfangled ship and hoped that its very existence would reduce the courage of the British.

In addition, the Nazis expected the imminent fall of Leningrad and for some reason decided that in this case the USSR Baltic Fleet would be guaranteed to flee to Sweden.

Leningrad held out, the Baltic Fleet did not escape anywhere, even Arctic convoys mainly suffered from aircraft and other ships, but not from the Tirpitz.

He basically tried the "snap and tick" tactic - appearing for a moment, and back to base.

But still, the battleship had a chance to take part in several real operations. Their scale is such that it allows us to believe that the Tirpitz was taken out of the parking lot only so that the Fuhrer would not have any questions about what he was doing.

Admiral Tirpitz as gravedigger of empires

Yuri Kirpichev How did the fleet destroy Germany (and not only it)? Why did World War I start in the first place? Many believe that the cause was the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. Or France’s desire to wash away the shame of 1870 and regain Alsace and Lorraine. Or Russia’s unjustified persistence in supporting Serbia. Or you just need to talk about a combination of many reasons.

But nothing seemed to foreshadow war, and until the last moment it seemed that it could be avoided. Here, for example, is what The

Times

on July 8, 1914, ten days after Gavrilo Princip’s shots: “

The visit of the English fleet to Kiel, the completion of which, although overshadowed by the tragedy in Sarajevo, was a great success and became an example of the brotherhood of all sailors peace and German hospitality.

The welcome was warm and sincere. The visit was not like the usual events that allow kings and emperors to feel like commanders-in-chief of their armies and fleets, with which they compete and sometimes trade blows. It was rather a symbol of brotherhood in arms - when in Kiel Emperor William raised the British admiral's flag for King George V, when Sir Georg Warrender and the President of the German Navy League exchanged inspired speeches in the Kiel town hall, when British and German sailors paraded along the embankment .

Brotherhood in arms, a joint parade, everyone rejoices, the German Emperor raises the British flag! I can’t even believe that there are twenty days left before the Great War - as it was called before the Second World War. And even then no one wanted to believe.

“ Unthinkable.

Impossible. Recklessness, scary tales, no one would dare to do this in the 20th century.

The darkness will blaze with fire, night killers will aim for the throat, torpedoes will tear apart the bottoms of unfinished ships and the dawn will reveal the faded sea power of our now defenseless island? No, it's incredible. Nobody will dare. Civilization, as before, will prevail. The world will be saved by many institutions: the interdependence of nations, trade and trade, the spirit of the social contract, the Hague Convention, liberal principles, the Labor Party, world finance, Christian charity, common sense ,” Churchill wrote poetically about this.

But he immediately asked worriedly: “ Are you completely sure of this?

"That the world will be saved.

A hundred years have passed, another enlightened age has arrived, people should have wised up, but this did not happen, and there is no confidence that a catastrophe will not happen. But here's what's important: the main cause of World War I was most likely the naval arms race. Of course, there were actually many reasons, but this one is the most likely and significant, at least in terms of the amount of effort and money invested in the construction of giant fleets. It was not without reason that the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries was called the “era of new marineism.”

Indeed, this was the period of the emergence and dominance of the theories of sea power of the American A.T. Mahan and the Englishman F. Colomb, whose influence went far beyond the admiralties and naval headquarters. It was also an era of industrial development, which brought new weapons into the hands of practitioners of naval warfare. And she herself gave birth to them, putting theories into practice and preparing the great armadas of their empires for the battle for world domination. The most famous of them were, perhaps, John Fisher in England and Alfred von Tirpitz in Germany. Probably, none of the maritime figures in history had such opportunities to influence the policy of their state. And they took advantage of the opportunity provided by fate!

It is to them that we owe the naval arms race in which they involved their countries and which, along with other European contradictions, ultimately led to a global conflict. They built huge battle fleets, but battleships do not like to stand idle; they must pay for themselves, being, for all their size and greatness, just a tool for doing business. War is the continuation of business by other means.

In addition, unlike land weapons, warships then quickly became obsolete and a gun, defiantly hung on the international naval stage - and armored monsters were a matter of national pride, they were scrupulously counted and taken into account, like nuclear warheads are now - this is a gun, like As a rule, it started shooting very soon! Including directors...

Remember the American-Spanish or Russian-Japanese war: no sooner had the United States built battleships than it attacked the decrepit empire, on which the sun had long set. As soon as Russia and Japan acquired armored fleets, they immediately fought in battle - for foreign land. Well, and most importantly, such a naval race led to a world war, because in those days it inevitably meant a challenge to the mistress of the world - England. With all the ensuing consequences.

The Man Who Seduced Germany

It seems that that long-ago war had a lot to do with the failure of Admiral Tirpitz's theory. He called it “risk theory” and it failed Germany. Let us return once again to the press of July 1914. Six days after the London article, L. Persius, a captain in the German Navy, reported in the Berliner Tageblatt

: «

The number of military personnel in the Navy was first seriously increased in 1912. We had 6,500 men then, 73,115 in 1913, and 79,386 now... In 1912 the British Navy numbered 136,461 men, and today that figure is 151,363. At the same time, the displacement of English ships as a whole is 2.205 million tons, and that of German ships is only 1.019 million... We paid 2 billion 245 million 633 thousand marks this year to our ground forces and navy. No nation in the world spends so much on its own armed forces. The Russians pay 1834.9 million, and the British 1640.9 million marks... the maintenance of the French ground forces and navy this year reached 1.44 billion marks. Austria's ground forces cost 575.9 million marks, the navy 150.7 million marks, Italy pays its army 369.4 million, and its fleet 260.2 million marks

».

The figures of the German captain fully explain why the war began - firstly, Germany and Russia were clearly preparing for it, and secondly, Germany began to pose a threat to the British fleet, and therefore to the maritime empire itself. It was not without reason that she was called the mistress of the seas!

So, on June 26, 1897, when the British were magnificently celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of the reign of Queen Victoria, 165 warships arrived at the Spithead roadstead. These included 21 1st class squadron battleships and 25 armored cruisers. Not only the queen was honored, but also her fleet. " Our fleet,

- wrote the Times, -

is without a doubt the most irresistible force that has ever been created, and any combination of the fleets of other powers will not be able to compete with it.

At the same time, it is the most powerful and versatile weapon the world has ever seen ."

Indeed, at the end of the 19th century, expensive naval programs were adopted one after another and entire series of powerful battleships of the same type were built. It was then that the majestic doctrine of the “two-power standard” was formulated, according to which the British fleet should be stronger than the combined other two largest fleets (that is, Russia and France). It meant the apotheosis of Britain's sea power!

But less than three years later, Germany decided to join the club of the strongest naval powers. Moreover, she did this so quickly that a few years later she took second place in the world (few people took the US fleet into account at that time), forcing Britain to change its European strategy and thereby laying the foundations for a future world war.

How and why did the Germans come to live like this? After all, Moltke the Elder himself, the winner of Austria and France, one of the creators of the German Empire and uncle of the no less famous Moltke the Younger, warned: “ Among the great powers, only England certainly needs a strong ally on the Continent, and it will not find a better one than a united Germany; no one but us meets the totality of British interests: we have never claimed power over the seas

».

Moltke was right! And Bismarck supported him, saying that we are in the very center of Europe and we should not quarrel with everyone. Especially with Britain. Napoleon also quarreled with her - and how did he end? What a cool guy he was!..

Why did the Germans depart from their covenants? The fact is that shortly before the indicated anniversary of Queen Victoria, on June 15, 1897, the talented Rear Admiral Tirpitz presented to the Kaiser’s attention a memorandum on the development of the German fleet. Britain was identified as the main enemy, and the main theater of conflict was the area between Heligoland and the Thames. Which, naturally, required a powerful armored fleet. Cruisers can’t fight the powerful Majestics! These were battleships, and Britain had a lot of them. The Kaiser and the Reichstag listened, on the basis of the memorandum, Tirpitz prepared a shipbuilding program and ensured that it was adopted as law.

This was required to discipline the naval department, the Reichstag and the Kaiser himself with his rich imagination. Germany could not afford to create a museum of different types of ships, and the fleet had to be developed, being confident that the allocation of funds would be guaranteed by law. Hochseeflotte began

- High Seas Fleet. Well, the fact that the Kaiser heeded it is not surprising, he was a dreamy man and adored military beauty, but the consent of the Reichstag is more curious. It seems that the people were a match for their Kaiser...

As for Alfred Tirpitz himself, by the end of the 1880s he was well known not only in government circles and the navy, but also among large industrialists - supporters of colonial expansion. He served as Minister of the Navy (Secretary of State for Maritime Affairs) for almost twenty years, from 1897 to 1916, and his concepts had a profound impact on the entire foreign policy of the Kaiser's Reich.

Therefore, the second shipbuilding program was developed taking into account the rivalry between Germany and England - the Anglo-Boer War was just going on, in which Germany helped the Boers. British cruisers intercepted German transports with weapons, and Tirpitz spoke frankly in December 1899 - right in the Reichstag! — that the program is provided in case of a collision with the most powerful fleet in the North Sea. It’s clear which one. But such a collision, he explained, requires creating a balance of forces in which the fight against the German fleet would become risky for the British. And 1900 became a turning point: Germany adopted the Maritime Law.

The preamble of which read: “ Under the current conditions, to protect German trade and commerce, we lack only one thing: a battle fleet strong enough for even the most powerful of possible enemies to see in a naval war with us a threat to their own superiority on the seas.”

».

So, Germany only lacked a powerful battle fleet that year!? How powerful? By the beginning of the 20th century, England had 38 squadron battleships and 34 armored cruisers, and Germany, respectively, only seven and two. However, the first program provided that in 5 years Germany would already have 19 squadron battleships and 10 armored cruisers. And according to the second program, extended until 1920, the basis of German naval power should have been 38 squadron battleships and 20 armored cruisers!

The Kaiser liked the admiral's ideas: he was a very warlike ruler - a sort of Partobon the Brave, dashing in appearance - and a great lover of military fun, ceremonies and rituals. Well, and weapons, of course, especially ones as representative as armadillos. Tirpitz himself wrote in his memoirs: “ Emperor Wilhelm II, while still crown prince, drew plans for ships and, not having a direct relationship with the Admiralty, got himself a special shipbuilder who helped him in his favorite pastime

" Just the German Peter I!

During maneuvers, he spent 24 hours a day on the deck of the flagship battleship, with “obvious pleasure” commanding fire on the floating shields. The Chief of the General Staff, Alfred Count von Waldersee, is even frightened by the Kaiser’s “naval passion”: “ This is too much for us!”

“As a child, the ruler read books about sea voyages, but now he independently develops “

ideal ships that the world has never seen before

.”

“ Our future lies in the waves

,” he declared in 1898 at the opening of Stettin harbor, frivolously challenging England’s previously inviolable naval power.

Having gotten rid of the wise Bismarck, who warned against brave nonsense, in Rear Admiral Tirpitz the Kaiser found an even more aggressive comrade-in-arms than himself, who saw a powerful fleet not only as a foreign policy instrument, but “an excellent medicine against the Social Democrats

"

For Tirpitz, the fleet was a national task that could unite the nation and strengthen the state. Captains of the growing industry, publishers and journalists, pastors, school teachers - all willingly paid the new excise taxes on champagne, which finance the construction of new ships. A naval magazine appeared; schoolchildren received awards for essays on naval topics; Artists and writers who devoted their creativity to naval affairs were awarded. Even the famous liberal Friedrich Naumann describes himself as “ a Christian, a Darwinist and a passionate navy enthusiast

”! The Navy Assistance Society became one of the most numerous organizations, and little Germans all wore sailor suits.

A characteristic detail: in June 1902, Wilhelm II, after a visit to Russia, left Revel, raising an arrogant and ambiguous signal on the Hohenzollern yacht as a farewell: “ The Admiral of the Atlantic Ocean greets the Admiral of the Pacific Ocean

" The hint of a division of spheres of influence not only pushed Russia into confrontation with Japan, but also warned Britain about the exorbitant ambitions of Germany...

"Risk Theory"

But to the point. When determining shipbuilding policy, Tirpitz had to take into account the fact that it was absolutely necessary for Germany to maintain a huge land army. Therefore, it could not allocate the same funds to the navy as Great Britain, the most powerful financial power in the world, which had only a small professional army. Based on these circumstances, Tirpitz developed his famous “risk theory”.

He believed that if it was possible to create a powerful formation of squadron battleships in the North Sea, they would pose a serious threat to England, especially given the scattered formations of the British fleet in remote naval theaters. And then she will not risk starting a war against Germany, since even in the event of victory, her naval power will be so undermined that some third power will rush to take advantage of the situation. On the other hand, the possession of a first-class navy should, according to Tirpitz, turn Germany into a valuable ally for anyone who dares to shake the power of the “mistress of the seas.”

We will talk about the advantages and disadvantages of the theory later, but its practical implementation is impressive. Patriotic and hardworking Germans rolled up their sleeves, tightened their belts - and things began to boil! German industry quickly proved that it was not much inferior to the British, and no country in the world has ever demonstrated such a growth rate in its navy! Following the first five battleships, the second came off the stocks, followed by the laying of the third - and as a result, by 1906, Germany had twenty squadron battleships, similar in tactical and technical data, which greatly facilitates the management of squadrons and the operation of ships. A brilliant achievement for the industry!

And although in the same year there was some break for technical reasons, which we will talk about later, it did not last long and even benefited Tirpitz’s plan.

Fischer vs Tirpitz

What about the supposed enemy? At first, the German naval programs did not cause much alarm in the British Admiralty. However, already in 1902, the first signs of concern appeared, and as a result, the reaction of England was not what Tirpitz expected. He predicted that it could not compete in a naval arms race with Germany while simultaneously maintaining a dominant position in other potential naval theaters, and would ultimately have to make concessions.

However, the Anglo-Japanese alliance concluded in 1902, which had an anti-Russian orientation, after the Tsushima defeat, freed the British from the need to keep heavy ships in Chinese waters. And then Britain emerged from its long and brilliant island isolation, returned to the continent and, following its old practice of creating alliances against the strongest European power, already in 1904 entered into an agreement with France and then with Russia. As a result, the Franco-Russian alliance was transformed into the Entente, while Germany's relations with Japan and Russia quickly deteriorated.

Before Britain's policy change, the Triple Alliance was stronger than France and Russia. Now Italy actually left it, warning that it would not fight with England, and Germany found itself surrounded by hostile states. There was no way she could count on winning if the fight dragged on. Therefore, on land, in order to avoid a disastrous war on two fronts, she had to come up with the dubious Schlieffen plan, this predecessor of the blitzkrieg. In such conditions, opening a third front, a naval one, was obviously suicidal, and even the arrogant Germans had to understand this. But they didn’t understand - they, like everyone else then, were fascinated by the greatness of the state, an absolutely necessary attribute of which was a powerful fleet. This greatness was measured by the number of armadillos! And since Germany has become the leader of continental Europe, then its fleet should be corresponding. And there it’s just a stone’s throw away from thoughts of rivalry with Britain...

But as for matters at sea, the Germans immediately received a harsh British response. When the famous reformer admiral J. A. Fisher became the first sea lord in October 1904, he immediately rang all the anti-German bells! The First Sea Lord is the head of the Royal Navy and all British Navy. He must be a professional, unlike the First Lord of the Admiralty, who chaired the Admiralty Committee, exercising political leadership - and serve as a counterweight to the latter when necessary.

Thus began the confrontation between Fischer and Tirpitz. We have already written that the latter hoped that the British fleet would be scattered across all seas and oceans - and then Fisher struck the first blow: he gathered the main forces in the waters of the mother country. The number of new battleships in the Mediterranean Sea was reduced from 12 to 8, and after them, all five modern battleships, which formed the main striking force of the English squadron in the waters of China, were recalled to England. If in 1902 there were 19 squadron battleships and armored cruisers based in the harbors of the metropolis, then in 1907 there were 64, that is, 3/4 of the total number. And they were concentrated specifically against Germany.

Fischer not only exploited the growing anti-German sentiment, but also fanned it in his struggle to increase the naval budget. Like Tirpitz, he welcomed publishers and journalists, gave the press a lot of materials and did not hide his bloodthirsty views (and he turned to Edward VII a couple of times with a proposal to suddenly attack and destroy the German fleet before it was too late). And many in Germany, including the Kaiser himself, believed in the reality of his plans. The rumor "Fischer is coming!" caused real panic in Kiel in January 1907: parents there did not let their children go to school for two days, waiting for the appearance of the English fleet on the horizon. It is unlikely that the Kaiser did not know about this and did not dream of retribution...

But Fisher played a special role in promoting a new round of the naval arms race associated with the Dreadnought. This famous battleship embodied the principle of “as many heavy guns of the same caliber as possible” ( all-big-gun

). And it was built unprecedentedly quickly. She was laid down on October 2, 1905, and in December 1906 she joined the fleet! Usually in those days it took at least three years to build a battleship.

If squadron battleships with a displacement of 13-15 thousand tons carried four 305-mm guns and developed speeds of up to 18 knots with the help of steam engines, then the turbine Dreadnought with a slightly larger displacement (18,100 tons) carried ten such guns, which also had same centralized fire control, with a speed of more than 21 knots! It is not surprising that the dreadnoughts practically reduced the combat value of the previous armored fleets to zero.

The sudden appearance of the Dreadnought upset all the plans of the rivals, and Fischer rejoiced: “ Tirpitz prepared a secret paper stating that the English fleet is 4 times stronger than the German one!” And we are going to support the British fleet at this level. We have 10 dreadnoughts ready and under construction, and not a single German one is laid down until March

»!

It would seem that Britain had secured unconditional leadership for a long time, but the joy was premature. The Germans accepted the challenge and in June 1906 laid down the Nassau, the lead ship of the first series of German dreadnoughts. The Law on Naval Construction of 1900 was amended: from now on, all new battleships will be only of the dreadnought type. They also became concerned with battlecruisers, and by 1920 Germany decided to have 58 battleships and battlecruisers.

As soon as all these facts became known in England, a political crisis erupted there, called the “sea panic of 1909.” A paradoxical situation arose: before the appearance of the Dreadnought, England had the overwhelming superiority of its battle fleet due to the accumulated stock of battleships. But the Germans built battleships as quickly as the British. This meant that now the backlog of the German fleet would be sharply reduced, and if efforts were made, it could be eliminated!

Unexpectedly, it turned out that England, having created a superweapon, with its own hands gave up dominance on the seas. Therefore, on January 25, 1910, Fischer, having received a peerage and the title of baron, was forced to resign. But I think he was pleased in his heart, because he achieved his goal: Viscount Reginald Esher had long recommended that he use the fear of Germany to increase the naval budget and strengthen the fleet: “ Fear of invasion is God’s mill, which will grind you a whole fleet of dreadnoughts and will support the spirit of belligerence in the English people!

»

In response to the German plans, the British decided to take force, and a new round of armaments began. In October 1911, Churchill took over as Secretary of the Navy and decided to raise the bar higher: create even more powerful dreadnoughts armed with 381-millimeter (15-inch) guns, which Fisher warmly recommended to him. The laying of the famous “fast division” of Queen Elizabeth-class battleships was included in the 1913 program. These excellent ships: with a displacement of 27,500 tons and good armor, they had a high speed of 25 knots, and their main artillery consisted of eight 381-mm guns. Thanks to Churchill's courage and persistence, they began to enter service as early as 1915 and played an important role in the Battle of Jutland. Tirpitz was late, and even more powerful German Bayerns with 381-mm guns appeared when the Kaiser had already abandoned the risk of linear battles.

The arms race consumed enormous amounts of money: if the cost of the Dreadnought, already outdated by the beginning of the war, was 1.7 million pounds sterling, then the battle cruiser Hood, laid down in 1916, already cost 12 million. Germany, rightly fearing a land war on two fronts, a third of the funds spent on defense were forced to be spent on the fleet (instead of forming and arming another 4-5 divisions).

What did she ultimately achieve? How did the “risk theory” prove itself?

Collapse of hopes and illusions

The rivals began the First World War with the following balance of forces: England had an overwhelming superiority in pre-dreadnought battleships (55 versus 25), which, however, no longer mattered much. Something else was more important: 25 battleships and 10 battlecruisers of the British against 17 and 6 German, respectively. Should we consider such a ratio (3:2) to satisfy the Tirpitz theory? Practice has shown that it is unlikely. And by the summer of 1916, when the moment of a decisive test of the strength of the fleets arrived, the situation had further worsened for Germany: 39 British heavy ships against 23 German ones. In other words, the situation was hopeless.

I don’t know when Tirpitz realized that Britain, having assessed the full danger of the challenge thrown at it, would never allow him to have a fleet comparable in power to its own, that the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet would remain a second fleet, unable to withstand the British in a long war. It seems very soon after the outbreak of war, when it became clear that he had failed to create a strategy to overcome the crushing naval superiority of the British. But was it really impossible to foresee the actions of the mistress of the seas? It would tolerate any strengthening of the German ground army, but the navy is fundamental! This is sacred for the maritime empire, which rests only on it.

Ultimately, the only achievement of the cherished line forces was the confirmation of the old adage that the second best fleet is as useless as the second best hand in poker when it comes time to lay the cards on the table. The Germans failed to protect their maritime trade, break the blockade and destroy enemy trade, or inflict unacceptable damage on the enemy.

The war began, and from its very first days the “risk theory,” which was aggressive in principle, because it was aimed at changing the world order, suddenly turned into its shadow practical side. Firstly, given their overwhelming numerical advantage, the British were more likely to take risks, as the Battle of Jutland showed. For the Germans, the risk could turn out to be too expensive, and fighting according to the principle of hit or miss was not their style.

Secondly, having realized this, the previously so decisive Kaiser now began to shake over his precious battleships - and did not let them into the sea! What if something happens to them? There are so few of them, they cost Germany so much, and there, in the cold North Sea, prowling the waves, peering with the pupils of their guns at the gray horizon and snapping their fangs, these bloodthirsty, these merciless Englishmen!

Indeed, several attempts by German battlecruisers to shell the English coast in order to undermine the morale of the population and lure part of the British fleet into the sea - under the attack of the main linear forces, ended in defeat in the battle of Heligoland, which could have turned into a defeat. And the fleet was sitting at the base in Wilhelmshaven.

In the pre-war years, in the wardrooms of German dreadnoughts, naval officers often raised a toast to “der Tag” - to the “Day” when the fleets of Germany and Britain would meet in a decisive battle. But the 14th year, the 15th, the spring of the 16th passed, and “der Tag” was still postponed, and Tirpitz - Tirpitz himself! - betrayed his dream: seeing that he was late in completing the construction of new battleships and that the German fleet could not lift the blockade of the North Sea, he became a supporter of unrestricted submarine warfare. German submarines, which before the war no one looked at as a serious type of naval force, unexpectedly showed extreme efficiency! It was not without reason that Churchill said that if he feared for England in that war, it was only because of German submarines.

However, after the dramatic sinking of the Lusitania and under severe pressure from the United States, the Kaiser rejected the proposal for unrestricted submarine warfare and did not even involve Tirpitz in a meeting on this issue. The admiral pretended to be offended, submitted another resignation letter and received it on March 17, 1916. Thus ended his military career. In my opinion, a complete fiasco.

And a month and a half later, the activity of the brainchild of his life, the linear forces of Germany, ended. The energetic new fleet commander, Scheer, obtained the Kaiser’s permission and finally did what Tirpitz so demanded: he brought his battleships to a decisive battle. "Der Tag" came on May 31, 1916, when the armadas of the two empires finally faced off. The grandiose Battle of Jutland lasted two days, in which 16 battleships, 5 battlecruisers and 6 battleships, not counting light cruisers and destroyers, took part on the German side against the British 28 battleships, 9 battleships and 8 armored cruisers!

But the decisive battle did not solve anything and did not lead to a strategic result. More precisely, the result was the preservation of the strategic advantage of the British: despite the fact that their losses in ships and people were greater, it became clear that it would not be possible to defeat them and lift the blockade of the German coast. As a result, the fleet only allowed the Kaiser to cling to the idea that it could still be used for bargaining at the peace conference.

That was the end of the combat activity of the German linear forces; they almost never went to sea again, with the exception of the last trip to the place of captivity, the English base of Scapa Flow. There they were sunk in the summer of 1919 by their own crews. This completed the practical application of Tirpitz’s “risk theory.” This was the result of twenty years of truly titanic efforts of the German people to create a powerful fleet.

But who knows how the war would have gone if Germany, instead of spending colossal costs on the fleet, had formed and armed at least a few additional divisions? Yes, using the power of its industry, engineering genius and the golden hands of the people, it would start decent aviation and army vehicles. Who knows if the “miracle on the Marne” would have happened if in August 1914 von Kluck had a couple of extra infantry corps, air supremacy and at least a thousand or two trucks?

PS To summarize, we can conclude that Tirpitz ended the 19th century, bringing down four empires in the process. But only recently, having already written this text, I learned that Edward Luttwak, a prominent military analyst and adviser to American presidents, also holds similar views. He wrote that if in 1910 Germany had sold its entire fleet to at least Brazil, England would have lost all interest in Germany, and things would not have come to war...

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.

See also:

- Sound Registers and Alaska Sales (01/12/2022)

- Stop the growing confrontation and turn to cooperation and dialogue (02/01/2021)

- The new US President and the prospects for American science (11/15/2016)

- Speech by Mikhail Kovalchuk in the Federation Council on September 30, 2015 (08.10.2015)

- Under the boot of William II and in the lettered Nicholas II. Two books about the victims of the “forgotten” war (01/27/2015)

- Rally in defense of science and education in Moscow June 6, 2015: speeches (06/09/2015)

- Honestly about Khodorkovsky and constitutional reform (02.10.2014)

- Fermi paradox, XXI century (08/13/2015)

- About the fate of the Main Astronomical (Pulkovo) Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences (03/28/2017)

Timber truck racing

Among his exploits was an attempt to intercept two convoys at once in March 1942. The first of them, PQ-12, was coming from Iceland to Murmansk, the second (QP-8) was heading towards it, from Murmansk.

The German squadron, which included the formidable Tirpitz, managed to slip right in front of the bow of one and behind the stern of the second convoy. Then everyone made excuses, citing the weather - they say, fog, zero visibility, and aerial reconnaissance was wrong.

The only victim of the hunt for the convoys was the Izhora, a Soviet timber carrier that accidentally fell behind its own in the fog. The commander of the Tirpitz had enough sense not to waste expensive charges on it - one of the destroyers of the squadron caught up with and sank the unfortunate vessel. And yet, “Izhora,” practically unarmed, held out against a sea wolf armed to the teeth for an hour and a half! Having managed to warn others about the attack.

Vain knight move

Another anti-convoy operation (codenamed “Knight’s Move”) was carried out in July of the same year. For convoy PQ-17, things ended badly - more than half of the ships sank. But Tirpitz did not touch them.

He simply went to sea, and this was enough to cause panic in the British Admiralty.

Having received intelligence data about the performance of the German “scarecrow”, the convoy was ordered to disperse and the escort vessels to fall behind. It turned out that the British command deliberately sacrificed transports to save the cruisers.

The convoy carried out the order. There was no loot for the battleship. The command decided that small German ships would cope with the task of catching the convoy ships one at a time. And so it happened. And the Tirpitz went back to the parking lot - away from British aircraft and submarines. It was a brilliant victory - the battleship didn’t even have to uncover its guns in order to win it.

From guns through mines

The Tirpitz also had a chance to take part in shooting along the coast. In September 1943, he moved to the shores of Spitsbergen. The buildings of the mining town remained there (before the war, coal was mined by the USSR and Norway) and German meteorologists worked for some time. They were fired upon by the British, who were pursuing their own goals when landing on Spitsbergen.

Revenge for the “dastardly attack” (of which as many as 1 person was the victim) was the visit of “Tirpitz”. The operation was beautifully called “Citronella” (aka “Sicily”). The huge battleship brought with it several hundred marines and tested its main caliber in real combat, firing at the miners' barracks. It looked scary, but the practical result would have been greater when shooting sparrows.

The combat biography of the battleship is exhausted by these three operations. The rest of the time she stood at anchor, repaired and spoiled the nerves of the British.

Main target

In September 1943, German ships led by the Tirpitz launched a raid on Spitsbergen. With the support of naval artillery, Hitler's troops landed on the island. Having destroyed a number of objects on Spitsbergen, the Germans left the island without trying to gain a foothold on it.

In the same month, the battleship, returning to base, was attacked by British mini-submarines. Four two-ton mines were dropped under the Tirpitz, as a result of which the ship suffered serious damage and was out of action for six months.

In the spring of 1944, when intelligence reported that the Tirpitz was about to return to service, the British command organized an operation codenamed “Tungsten”.

The main striking force was two wings of deck-based torpedo bombers and Fairey Barracuda dive bombers operating from an aircraft carrier.

During the air raids, 122 German sailors were killed and another 316 were injured, but the main goal was not achieved: the Tirpitz escaped serious damage.

During the summer of 1944, the British prepared several more major attacks on Hitler's main battleship, but they were thwarted either due to bad weather or due to the strengthening of German air defense.

In September 1944, British pilots attacked the Tirpitz from the Soviet airfield Yagodnik near Arkhangelsk. The result of this attack was the loss of seaworthiness by the battleship, as a result of which the ship began to serve as a coastal battery.

"Tirpitz" in the Norwegian Altenfjord, circa 1943-1944. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org/ US Naval Historical Center

Simple methods of invulnerability spell

In fact, everything was simple. The battleship was invulnerable because of its own merits, the characteristics of the northern nature, but even more so because of the mistakes of the British.

- Visibility in Norway is poor. The battleship changed colors in June 1942 - the coloring acquired northern camouflage. So the British bombed at random.

- The Tirpitz's air defense was good - a rare raid did not cost the British several aircraft.

- The battleship's crew also achieved excellent results in installing smoke screens.

- British pilots were taught to bomb areas. This was done in Dresden, but the area of the battleship is much smaller. So the bombs basically reduced the fish stocks of the North Sea.

- Several guided torpedoes inexplicably... got lost along the way.

- One of the armor-piercing bombs that damaged the Tirpitz, according to the results of the test (it was carried out by the Germans), contained half the explosives required by the standard.

It is clear that it is not easy to fight such “conspiracies”. But some strikes reached their target - before the final sinking, the Tirpitz received damage several times that precluded independent progress (in September 1943 and April 1944).

Some bombing and mining by mini-submarines yielded results. As a result, this destroyed the battleship - it was unable to fully defend itself from the last attack.

Captain Lunin and the attack on the Tirpitz

The question of who sank the Tirpitz is closed. This was done by British bombers on November 12, 1944. But the USSR also claims credit for the hunt for the battleship. The captain of the K-21 submarine, N.A. Lunin, during the counteraction to the “Knight's Move,” fired torpedoes at the Tirpitz and the destroyer accompanying it. Then in his report he reported hearing explosions and suggested that he had damaged the Tirpitz and sank the second ship.

But such losses were not recorded among the Germans.

Almost certainly Lunin's torpedoes missed and exploded as they fell to the bottom. Data on his course indicate that his chances of getting into the battleship were minimal. This does not discredit the captain's integrity - he at least tried, and did not claim that he observed a hit. But Tirpitz is not his prey.

K-21 attack

In the spring of 1942, the battleship, accompanied by destroyers, went hunting, intending to intercept convoys PQ-12 and QP-8. The Allies were helped by bad weather, due to which the Tirpitz was unable to reach the target. After the Germans realized that they had been discovered by British aircraft, the battleship was immediately ordered to return to base.

In July 1942, Tirpitz was to become the main figure in Operation Horse's Move: an attack by a group of German ships on the PQ-17 convoy. But in fact, the battleship did not take part in it: after the Nazis learned that the British escort ships had left, leaving the transports alone, the Tirpitz went back to the base. German torpedo bombers and submarines coped with the hunt for lone merchant ships.

On July 5, 1942, the battleship was attacked by the Soviet submarine K-21 under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Nikolai Lunin . The conditions of the attack were difficult; the submarine commander did not visually observe the destruction of the target, but, focusing on the sounds of explosions, he assumed the defeat of the Tirpitz or one of the escort ships.

In the Soviet years, damage to the battleship during an attack by the K-21 submarine was considered reliable, but a later analysis of German documents casts doubt on this. Most likely, the torpedoes did not reach their target.

Article on the topic

The secret of 100 years of aging. Who blew up the battleship Empress Maria?

Posthumous fame

During the implementation of Operation Catechism on November 12, 1944, the British dropped several Tallboys onto the Tirpitz. One reached the goal; the hit caused a fire and detonation of the ammunition. The battleship capsized and sank.

There was no need to look for the place of death on the map - the hull of the battleship was visible in Hockeybotn Bay above the surface. There he waited for the end of the war.

After peace was concluded, Norway cut up the Tirpitz until 1957. A significant part of the metal... was sold to Germany. Many of the fragments decorate museums, and souvenir jewelry was made from some of them. Several pieces of the battleship were used to repair roads. The bow part is still lying on the bottom.

Not far from the final resting place of the Tirpitz there is a monument to the dead crew members. The monument is dubious, but you can’t fight with the dead...

The fate of the battleship also affected the surrounding nature.

After the war, new lakes appeared in the Hockeybotn Bay area. They were formed when the craters from the Tallboys filled with water - the well-aimed British managed to miss the ship by kilometers.

After the death of the battleship, a new, glorious biography was invented for him. The British were proud of its destruction as if the Tirpitz had personally sent half of their fleet to the bottom. In modern computer games, “destroying the Tirpitz” is a common task for a superhero.

Well, at least he will fight on the screen. In reality, the Tirpitz did not recoup even a tenth of the funds invested in it, and what the British were afraid of was their shortcoming, and not the advantage of the ship. Let him work it out now.

Operations against Tirpitz and the death of the battleship

The battleship Tirpitz haunted the British military leadership. After the loss of the Hood, the British understood very well what the German flagship was capable of.

In late October 1942, Operation Title began. The British decided to sink the Tirpitz using human-controlled torpedoes. They planned to tow them to the battleship's mooring site in a submerged position using a fishing boat. However, almost at the very entrance to the harbor with the Tirpitz, a strong wave arose, which caused the loss of both torpedoes. The British sank the boat, and the sabotage team left on foot for Sweden.

Almost a year after these events, the British began a new operation to destroy the ship, it was called Source. This time they planned to destroy the battleship with the help of ultra-small submarines (Project X), which were supposed to drop explosive charges under the Tirpitz hull. Each of these boats had a displacement of 30 tons, a length of 15.7 m and carried two charges, each of which contained almost two tons of explosives. Six mini-submarines took part in the operation; they were towed to the site by conventional submarines.

The sabotage submarines were supposed to attack not only the Tirpitz; additional targets were the Scharnhost and Lützow.

Only two boats (X6 and X7) managed to dump their charges under the bottom of the ship. After which they surfaced, and their crews were captured. The Tirpitz did not have time to leave the parking lot; the explosions caused significant damage to it. One of the turbines was torn off the frame, the frames were damaged, the main caliber “C” turret was jammed, and several compartments were flooded. All rangefinders and fire control devices were destroyed. The battleship was disabled for a long time. The captains of the submarines X6 and X7 were awarded Victoria Crosses in their homeland - the highest military awards of the empire.

The Germans managed to repair the Tirpitz only in the spring of 1944 and it became dangerous again. It should be noted that the repair of the battleship after very severe damage, carried out without a dry dock, is a real achievement of German sailors and engineers.

At this time, the British begin a new operation against the Tirpitz - Tungsten (Tungsten). This time the emphasis was on the use of aviation. Several British aircraft carriers were involved in the operation. Two waves of Fairey Barracuda torpedo bombers carried not torpedoes, but different types of bombs. As a result of the raids, the ship was severely damaged. The bombs were unable to penetrate the armored hull of the battleship, but the superstructures were seriously damaged. 123 members of the ship's crew were killed and another 300 were wounded. The restoration of the Tirpitz took three months.

Over the next few months, the British carried out several more raids on the ship (Operations Planet, Brawn, Tiger Claw and Mascot), but they did not bring much results.

On September 15, Operation Paravane began. RAF Avro Lancaster aircraft took off from an airfield near Arkhangelsk and headed for Norway. They were armed with 5-ton Tallboy bombs and underwater mines. One of the bombs hit the bow of the ship and caused such damage that the battleship practically lost its seaworthiness. At the end of 1944, the Germans no longer had the opportunity to transport the Tirpitz into dry dock and carry out serious repairs.

The battleship was moved to Sørbotn Bay off the island of Håkøya and turned into a floating artillery battery. At this location he was within reach of aviation from British airfields. The next raid (Operation Obviate) was unsuccessful due to bad weather.

The fatal raid for the ship was on November 12 (Operation Catechism), during which three heavy-duty Tallboy bombs hit the battleship. One of them bounced off the turret armor, but the other two pierced the armor belt and led to the sinking of the Tirpitz. Of the 1,700 crew members, 1,000 died, including the ship's commander. The passive behavior of the Luftwaffe, whose planes made no attempt to interfere with the bombing, is still incomprehensible.

After the end of the war, the wreckage of the battleship was sold to a Norwegian company, which dismantled the remains of the ship until 1957. The bow of the Tirpitz remained lying where the ship took its last battle.

Not far from the site of the death of the battleship, a monument was erected to the dead crew members.

The Tirpitz is one of the most famous warships. Hundreds of articles and books have been written about the battleship, and films have been made about it. Of course, the history of this ship is one of the brightest pages of the Second World War.

Despite the fact that the Tirpitz practically did not use its guns in battle, its influence on the course of the war in the North Atlantic and Arctic was enormous. After its destruction, the Allies were able to transfer significant naval forces to other theaters of war: the Pacific and Indian Ocean, which significantly worsened Japan's position.