Raiders in the Atlantic

Before the attack on Poland, Germany secured itself in case the Western allies did not calmly watch as the Wehrmacht tore apart the army of Pilsudski’s hapless heirs.

Already at the end of August 1939, submarines and two “pocket battleships” - the battleships Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee - went to sea. They were faced with the task of acting against merchant shipping in the Atlantic if the British and French wanted to intervene in the conflict. Surface raiders divided the ocean in half: the Deutschland remained in the North Atlantic, the Spee went to the South.

After the outbreak of World War II, they began work. The first did not achieve great success, but the second went down in history as a more successful “corsair”. Over the course of three months, eluding enemy search parties, the Spee sank nine ships totaling fifty thousand gross tons.

But fortune is a capricious lady.

In December 1939, the raider was discovered by British cruisers and took part in battle near La Plata Bay - which was the beginning of its end.

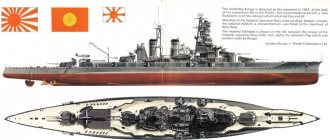

Heavy cruiser "Admiral Graf Spee"

Falklands final

On the morning of December 8, Spee's squadron approached the English base of Port Stanley on the Falkland Islands. The purpose of the exit was to attack the base and capture the English governor - a kind of symmetrical action in retaliation for the capture of the governor of German Samoa.

It immediately became clear that something had gone wrong. In Port Stanley Bay, the characteristic three-legged masts of two large ships, called “squadron battleships” in the first report, were clearly visible. The Germans, who believed that the maximum they could meet there was “Canopus,” did not want to believe that this was the end. The British battlecruisers entered the South Atlantic - the “killers of trade killers”: faster than any of the armored cruisers, equipped with the main caliber of dreadnoughts.

In the Port Stanley roadstead there was a detachment of ships hastily pushed out of England, the basis of which was the battlecruisers Invincible and Inflexible, classmates of Australia, which Spee avoided meeting by going to the eastern part of the Pacific Ocean. These ships arrived in Port Stanley just a day earlier, on December 7th. Spee had the opportunity to sneak past the base and get, albeit illusory, a chance to look for a path in the Atlantic, having plundered a lot along the way on English communications with Latin America. But he poked his head straight into the lair.

The Falklands Battle became a benefit for the English commander, Vice Admiral Frederick Doveton Sturdee. Sitting in the chair of the Chief of the General Staff of the Admiralty, Sturdy, with his polished secular stubbornness, so infuriated John Fisher (who was already furious in temperament) that he made titanic efforts to push him somewhere to the seas, to command.

Battlecruiser "Invincible"

Photo:

Sturdy shrugged and “chucked out.” He didn't care. To catch Spee is to catch Spee. Sturdy was not distinguished by an original vision, like the same Fisher, who literally broke his knee and rebuilt the British fleet. He did not shine with tactical talents and command competencies, like the owner of the Big Fleet, John Jellicoe. He did not know how to delight people, like the idol of the fleet, David Beatty, who led the vanguard of this fleet - the 1st squadron of battlecruisers - into battle. He simply built a career without making irreparable mistakes. He was, following Evelyn Waugh's definition, "an officer and a gentleman", a completely typical product of the naval corporation of the British Empire.

In this fight, he also did not make a single mistake, although before the fight, it seems that he made every effort to ensure that it did not take place. In 1919, the poisonous and bilious boor Fischer, already with one foot in the grave, would once again spit in the back of his “adored” Sturdy: “If this idiot had been allowed to collect with him all the shirts that he had planned, he would still be catching Spee in the Atlantic."

Nevertheless, Sturdy's fight played out as it should. Having started the chase in the morning in conditions of ideal visibility, after fussing a little with the choice of position, he caught up with both German armored cruisers and took them to pieces.

Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee

Photo:

Spee didn't have the slightest chance. The worn-out vehicles of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were barely capable of squeezing out 20 knots, and the main armament consisted of sixteen 210-mm main caliber guns between them. Sturdy's battlecruisers could make 26 knots, also carrying sixteen guns between them, but of 305 mm caliber.

Into close combat shouting “Board!” Sturdy did not intervene - his artillery allowed him to work from a distance. How much the war at sea has changed in the ten years after the appearance of the dreadnoughts can be seen from the final ammunition consumption.

"Invincible" fired 513 305-mm shells, "Inflexible" - 661 such shells. Is it a lot or a little? For comparison: the entire detachment of battleships of Admiral Togo Heihachiro in the Battle of Tsushima, carrying the same sixteen 305-mm guns, during the entire (!) general battle that decided the fate of the Russo-Japanese War, fired only 446 shells of this caliber - three times less than they allowed themselves officer and gentleman Doveton Sturdee in a minor peripheral skirmish of the First World War.

Battle of the Falkland Islands. Drawing by A. Hansen

Image: Peter Kamenchenko archive

The Scharnhorst sank with its entire crew, including Admiral Spee and his son. It was difficult to survive in water with a temperature of 6-7 degrees Celsius, and the British launched a rescue operation only after they sank the Gneisenau. It managed to take almost 300 people, but many died a few hours later from hypothermia (a total of 190 people survived).

The light cruisers of Spee separated in the middle of the battle and tried to escape, but were intercepted by the British light cruisers. As a result of the pursuit, the Dresden managed to escape (it was pinned down and drowned in March 1915 off the Chilean coast), and the Nuremberg and Leipzig were intercepted and sunk. The second son of Max von Spee died on the Nuremberg.

Imaginary convoy

On the morning of December 13, Spee was looking for an enemy convoy off the coast of Uruguay. Noticing the masts on the horizon, the Germans decided that the target had been discovered. But they were mistaken - it was the English squadron of Commodore Harwood: the heavy cruiser Exeter and the light cruisers Ajax and Achilles.

The English warships did not embarrass the raider commander Langsdorff. He decided that in front of him was a convoy escort - one cruiser and two destroyers. This means that if they are destroyed, a tasty prize awaits him - an order from merchant ships.

Langsdorff decided to attack.

But this turned out to be a mistake. There was no convoy, and the imaginary destroyers turned out to be cruisers. Alas, Langsdorff realized this only after starting the battle.

Battle of the Belomor pack

The tragedy of Maximillian von Spee's squadron revealed another important aspect of the war at sea, new in new conditions. The leadership of the naval war quickly began to leave the bridges of the proud, handsome flagships into the dusty rooms of naval headquarters. Rangefinders and reconnaissance of light forces in sectors began to give way to pictures of radio interceptions and messages plotted on maps of the situation.

Powerful coastal radio stations and relay ships made it possible to control squadrons located in the other hemisphere of the planet. The war at sea became global and required the strengthening of the coastal headquarters, which had previously performed decorative and administrative functions.

In the story of the Spee squadron, the most unpleasant defeat that the British suffered was not the battle at Coronel, but the realization of the total dysfunction of the Main Naval Headquarters. Lack of personnel, decomposition and delegation of tasks, and a structured work procedure. Finally, the complete lack of maritime intelligence. John Fisher, the main vessel of poison in the British Navy, at the beginning of the war casually called the intelligence department of the Main Naval Headquarters “the most effective collector of newspaper clippings in history.”

It was in parallel with the plot around the Spee squadron that Britain began to create a normal functional fleet headquarters - as an operational control body. At the same time, reconnaissance also intensified: the so-called “Room 40” appeared - a radio interception and decryption service that received at its disposal the codes of the German fleet, thrown from the stranded cruiser Magdeburg in the Baltic and recovered by Russian divers.

The naval war, which began, according to the famous joke, “with a pack of Belomor”, acquired a solid methodological basis.

A battle without winners

Harwood decided to take the Spee in a pincer movement, dividing his ships. On one side Exeter was firing at him, on the other - Ajax and Achilles. But the raider turned out to be a formidable opponent. Concentrating the fire of his six 280 mm guns on the Exeter, he quickly achieved success. Having received the full force from the Germans, the badly damaged “Englishman” withdrew from the battle.

View of Achilles from Ajax

However, Langsdorff underestimated Harwood.

On the same topic

The impossible: how a German submarine broke through to Scapa Flow

While “Spee” was smashing “Exeter” with its “suitcases,” “Ajax” and “Achilles” were doing the job. They brazenly approached the “German” and, bombarding him with 152-mm shells, achieved their goal. Leaving their wounded brother alone, Langsdorff transferred the full power of the guns to the two English ships.

The raider's fire was still accurate.

Soon Ajax received two shots from his main caliber and lost half of his artillery. In this situation, it was dangerous to continue the battle, so Harwood stopped the battle, withdrawing his ships to a safe distance.

But then Langsdorff surprised the British: instead of pursuing, he headed for Montevideo. Ajax and Achilles followed. When Harwood realized that the raider was heading to a neutral port, he had to leave him alone.

On December 14, the Admiral Graf Spee entered the harbor of the capital of Uruguay and three days later was scuttled by its crew. The death of this ship is surrounded by myths that hide the true cause of what happened.

Damaged Exeter after the battle

Arena of 180 million square kilometers

The main action of the upcoming drama was just getting ready to unfold on the fields of Europe, and few of the ordinary people, and even the military, anxiously reading the pages of newspapers and telegrams in the first days of August 1914, followed what was happening on the other side of the Earth. However, in the vastness of the greatest ocean on the planet, capable of more than containing all the earth’s continents, fate was dealing the cards of a new game, the results of which would determine the fate of the surrounding lands and peoples for decades to come.

At the center of the situation, in the Caroline Islands, was the cruising, also known as the East Asiatic, squadron of the Kaisermarine - the German navy. The squadron consisted of two armored cruisers - Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and four light cruisers - Dresden, Emden, Leipzig and Nuremberg.

The squadron commander, Vice Admiral Maximilian Count von Spee, faced a difficult choice. His main base was Qingdao, a German-owned Chinese port on the western coast of the Yellow Sea. The fate of the city and the entire German colony of Kiao Chao, as well as all other German colonial possessions in the Pacific, now depended on the upcoming “dealing of the cards.” On the one hand, the main issue was the time and conditions for Great Britain’s entry into the war (it was the sea communications of the British Empire that were the primary goal of the cruising squadron); on the other hand, the Royal Navy, possessing unconditional superiority in forces, could quickly blockade Qingdao, turning a convenient port into a mousetrap . The way home was thus cut off.

Maximilian von Spee

Photo:

The blockade in itself, however, could not lead to the fall of the city, which relied on a fairly developed colony and had close economic ties with the surrounding territories of China. The British clearly did not have enough ground forces to siege and storm Qingdao from land during the war in Europe. Under these conditions, the main threat to the very existence of the German colony was Japan, an Entente ally, which had both a strong fleet and a sufficient ground army nearby.

Under these conditions, von Spee's only hope was active actions on communications that would force the British and their allies to disperse their forces. The question of direction remained: moving north meant going straight into the arms of the Japanese, whose large fleet controlled the surrounding waters quite tightly, and a dense network of Royal Navy coaling stations grew to the south and west of the Caroline Islands, covered by superior forces, including a battle cruiser "Australia".

Photo:

As a result, the choice fell on the eastern direction. Von Spee's squadron headed to the shores of Chile, where the Germans had the opportunity, firstly, to obtain coal, and secondly, to carry out short repairs: Chile, despite its neutrality, was friendly towards Germany.

Light cruiser Emden

Image: Peter Kamenchenko archive

The Western direction, however, did not go unnoticed. Von Spee dispatched the light cruiser Emden, which would soon become one of the most famous German ships of the war, to hunt for British trade in the waters of Southeast Asia. The cruiser Nuremberg was sent to Honolulu, which belonged to the neutral United States, for news: the telegraph cables leading to the German island possessions had already been cut, and the range of von Spee's radio stations was not enough for direct communication with the Reich.

Myth one - they chickened out and flooded

On the same topic

Aircraft carriers versus submarines: the first victory over the “gray wolves”

During the battle with the British, the battleship received severe damage. Langsdorff hoped to be repaired in Uruguay, but the pro-British government of that country refused to help. Uruguayan shipyards did not undertake the repair of the German ship.

The British were concerned about the presence of the Spee in Montevideo. They believed that he could go out to sea at any moment and disappear into the ocean. But Harwood could not delay the raider with two light cruisers.

It is believed that he was helped by rumors that a powerful English squadron with the battle cruiser Rinaun and the aircraft carrier Ark Royal was already waiting for the German raider at the exit from the harbor. Allegedly, they put so much pressure on Langsdorff's nerves that he showed cowardice and chose to sink his ship without fighting.

But he simply could not fight.

To find out the condition of the Spee, Berlin urgently sent its expert to Montevideo. Having studied the issue, the latter reported to Germany that in a battle with English cruisers, the battleship received two serious damages: the galley with provisions was destroyed and the command and rangefinder post was out of order. As a result, access to the sea was excluded. Firstly, without a galley and provisions, it is impossible to feed the crew on a campaign. Secondly, with a faulty control unit it is impossible to shoot accurately in battle.

Repairs required two weeks, but Uruguay gave only three days. Seeing no other choice, Langsdorff destroyed the ship on December 17, 1939. Three days later he shot himself to avoid being branded a coward.

Burning "Admiral Count Spee"

"Admiral Count Spee". Pirate everyday life and the end of the sawn-off battleship

"Admiral Count Spee" in Montevideo. Last stop

On the evening of December 17, 1939, a crowd of thousands of spectators from the shores of La Plata Bay watched a breathtaking spectacle. The war, which was already raging with might and main in Europe, finally reached carefree South America and no longer as newspaper reports. Angular, with sharp chopped shapes, like a medieval Teutonic knight, the German raider “Admiral Graf Spee” moved along the fairway. Those versed in naval history shook their heads thoughtfully - the circumstances were too reminiscent of the events of 120 years ago, when the residents of Cherbourg escorted the Confederate cruiser Alabama to battle with the Kearsarge. The crowd was thirsty for battle and the inevitable bloodshed: everyone knew that an English squadron was guarding the entrance to the Spee Bay. The “pocket battleship” (an English term; the Germans called such ships sawn-off battleships) leisurely left the territorial waters, the anchors being released rumbled in the hawse. And then explosions thundered - a cloud of smoke and flame rose above the ship. The crowd sighed in fascination and disappointment. The much anticipated battle did not take place. Bet and deals collapsed, newspapermen were left without fees, and Montevideo doctors were left without work. The career of the German “pocket battleship” Admiral Graf Spee was over.

Sharp dagger in a narrow sheath

In an effort to humiliate and trample Germany into the mud after the First World War, the Entente allies entangled the defeated country with many restrictions, primarily in military terms. It was quite difficult to determine from a long list with no less impressive additions, clarifications and explanations: what could the vanquished have in their arsenal and what should it look like? With the death of the most combat-ready core of the High Seas Fleet by self-sinking in Scapa Flow, the British lords finally breathed easier, and the fog over London became less gloomy. As part of a small “club for the elderly”, which with great stretch can be called a fleet, the Weimar Republic was allowed to have only 6 battleships, not counting the limited number of ships of other classes, which were actually battleships of the pre-dreadnought era. The pragmatism of Western politicians was obvious: these forces were quite enough to confront the Navy of Soviet Russia, the state of which by the beginning of the 20s was even more dismal, and at the same time completely insufficient for any attempts to sort out relations with the victors. But the larger the text of the agreement, the more clauses it contains, the easier it is to find appropriate loopholes and room for maneuver in it. According to the Treaty of Versailles, Germany had the right to build new battleships with a tonnage limit of 10 thousand tons instead of old ones after 20 years of service. It just so happened that the time in service of the Braunschweig and Deutschland-class battleships, which entered service in 1902–1906, was approaching the cherished twenty-year mark already by the mid-1920s. And just a few years after the end of the First World War, the Germans began designing ships for their new fleet. Fate, in the person of the Americans, presented the vanquished with an unexpected but pleasant gift: in 1922, the Washington Naval Agreement was signed, imposing restrictions on the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of ships of the main classes. Germany had a chance to create a new ship from scratch, being within the framework of less stringent agreements than those of the Entente countries that defeated it.

At first, the requirements for new ships were quite moderate. This confrontation in the Baltic was either with the fleets of the Scandinavian countries, which themselves had plenty of junk, or a reflection of the “punitive” expedition of the French fleet, where the Germans considered the main opponents to be intermediate-class battleships of the Danton type - it is unlikely that the French would have sent their deep ships to the Baltic Sea seated dreadnoughts. At first, the future German battleship confidently resembled a typical coastal defense ship with powerful artillery and a low side. Another group of specialists advocated the creation of a powerful 10,000-ton cruiser capable of fighting any of the “Washingtonians,” that is, cruisers built taking into account the restrictions imposed by the Washington Maritime Agreement. But again, the cruiser was of little use in the Baltic, and the admirals were scratching their heads, complaining about insufficient armor. There was a design impasse: a well-armed, protected and at the same time fast ship was required. A breakthrough in the situation came when the fleet was led by Admiral Zenker, former commander of the battlecruiser Von der Tann. It was under his leadership that German designers managed to cross a “hedgehog with a snake,” which resulted in the I/M 26 project. Ease of fire control and space saving led to the optimal 280-mm main caliber. In 1926, the French, tired of victory, left the demilitarized and occupied Rhineland, and the Krupp concern could guarantee the timely production of new barrels. Initially, the ship was planned to be equipped with intermediate calibers - universal 127 mm guns, which was an innovative and progressive solution for those years. However, everything that looks great on paper does not always translate into metal (sometimes, fortunately) or is implemented in a completely different way. Conservative admirals, who always prepare for naval battles of the bygone war, demanded a return to the 150-mm medium caliber, which would be complemented by 88-mm anti-aircraft guns. The subsequent service of “pocket battleships” showed the fallacy of this idea. The center of the battleship turned out to be overloaded with weapons, protected, moreover, for the sake of economy, only by anti-fragmentation shields. But this was not enough for the admirals, and they pushed through the installation of torpedo tubes, which had to be placed on the upper deck behind the main tower. We had to pay for this with protection - the main armor belt “lost weight” from 100 to 80 mm. The displacement increased to 13 thousand tons.

The first ship of the series, serial number 219, was laid down in Kiel at the Deutsche Veerke shipyard on February 9, 1929. The construction of the lead battleship (in this way, so as not to confuse the “enlightened sailors” and their friends, new ships were classified) did not proceed very quickly, and under the pretentious name “Deutschland” it was delivered to the fleet on April 1, 1933. On June 25, 1931, the second unit, the Admiral Scheer, was laid down at the state shipyard in Wilhelmshaven. Its construction was already proceeding at a fairly rapid pace. Meanwhile, the appearance in Germany of some suspicious “battleships” that had agreed-upon dimensions on paper, but in reality looked very impressive, could not help but worry its neighbors. First of all, the French, who hastily began to design “hunters” for the German “Deutschlands”. The fears of the French were embodied in the ship's steel of the battlecruisers Dunkirk and Strasbourg, which were superior to their opponents in all respects, although they were much more expensive. German designers needed to somehow respond to the appearance of the “Dunkirks”, which caused some pause in the construction of the series. It was already too late to make fundamental changes to the project, so we limited ourselves to revising the reservation system of the third ship, bringing it to 100 mm, and instead of 88 mm anti-aircraft guns, they installed more powerful 105 mm ones.

"Admiral Graf Spee" leaves the slipway

On September 1, 1932, on the slipway vacated after the launch of the Scheer, the “battleship C” with construction number 124 was laid down. On June 30, 1934, the daughter of the German admiral Count Maximilian von Spee, Countess Huberta, broke a traditional bottle of champagne against the side of the ship named after her father . On January 6, 1936, Admiral Graf Spee joined the Kriegsmarine. In memory of the admiral, who died in 1914 near the Falkland Islands, the new battleship bore the coat of arms of the house of von Spee on the bow, and the Gothic inscription “CORONEL” was made on the tower-like superstructure in honor of the victory won by the admiral over the English squadron off the coast of Chile. The Spee differed from the first two battleships of the series in its enhanced armor and developed superstructure. A few words should be said about the power plant of the Deutschland class ships. Naturally, these so-called “battleships” were not intended for any protection of the Baltic waters - their main task was to disrupt enemy communications and combat merchant shipping. Hence the increased requirements for autonomy and cruising range. The main power plant was supposed to be diesel engines, in the production of which Germany has traditionally maintained leadership. Back in 1926, the famous company began developing a lightweight marine diesel engine. For the experiment, a similar product was used as an economic propulsion installation on the light cruiser Leipzig. The new engine turned out to be capricious and often failed: since the design was lightweight, it created increased vibration, which led to breakdowns. The situation was so serious that Spee began to explore options for installing steam boilers. But the MAN engineers promised to bring their brainchild to fruition; moreover, the requirements for the project did not provide for a difference in the types of installed engines, and the third ship of the series received the 8 main nine-cylinder diesel engines provided for it with a total power of 56 thousand hp. By the beginning of World War II, the engines on all three ships had been brought to a high degree of reliability, which was proven in practice by the first raid of the Admiral Scheer, which covered 46 thousand miles in 161 days without serious breakdowns.

Pre-war service

"Spee" passes by the Kiel Canal

After various tests and inspection of equipment, the “pocket battleship” took part in the naval parade held on May 29, 1936, which was attended by Hitler and other senior officials of the Reich. The reviving German fleet was faced with the problem of training personnel, and on June 6, the Graf Spee, taking on board midshipmen, set sail for the Atlantic to the island of Santa Cruz. During the 20-day trip, the operation of the mechanisms, primarily diesel engines, is checked. Their increased noise was noted, especially on the main stroke. Upon returning to Germany - again exercises, training, training voyages in the Baltic. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Germany took an active part in these events. As a member of the “Non-Intervention Committee,” whose function was to prevent the supply of military supplies to both warring parties, the Germans sent almost all of their large ships to Spanish waters. The Deutschland and Scheer first visited Spanish waters, then it was the turn of the Graf Spee, which set sail for the Bay of Biscay on March 2, 1937. The “pocket battleship” kept its watch for two months, visiting Spanish ports in between and encouraging the Francoists with its presence. In general, the activities of the “Committee” over time began to be more and more mocking and one-sided in nature, turning into a farce.

"Pocket Battleship" at the Spithead naval parade

In May, Spee returned to Kiel, after which she was sent as the most modern German ship at that time to represent Germany in the naval parade on the Spithead roadstead, given in honor of the British King George VI. Then again a trip to Spain, this time short-term. The “pocket battleship” spent the remaining time before the big war in frequent exercises and training voyages. The fleet commander raised the flag on it more than once - the Spee had a significant reputation as an exemplary ceremonial ship. In 1939, a large overseas cruise of the German fleet was planned to demonstrate the flag and technical achievements of the Third Reich, in which all three “pocket battleships”, light cruisers and destroyers were to take part. However, different events took place in Europe, and the Kriegsmarine no longer had time for demonstration campaigns. The Second World War began.

The beginning of the war. Pirate everyday life

The German command, in the conditions of the increasingly deteriorating situation in the summer of 1939 and the inevitable clash with Poland and its allies England and France, planned to start a traditional raider war. But the fleet, whose admirals were running around with the concept of chaos in communications, was not ready to create it - only the Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee, which were constantly in heavy use, were ready for a long trip to the ocean. It also turned out that hordes of raiders converted from commercial ships exist only on paper. To save time, it was decided to send two “pocket battleships” and supply ships to the Atlantic to provide them with everything they needed. On August 5, 1939, the ship Altmark left Germany and went to the USA, where it was supposed to take on board diesel fuel for the Spee. The “pocket battleship” itself left Wilhelmshaven on August 21 under the command of Captain Zur See G. Langsdorff. On the 24th, the Deutschland followed its sistership, working in conjunction with the tanker Westerfald. The areas of responsibility were divided as follows: Deutschland was supposed to operate in the North Atlantic, in the area south of Greenland - Graf Spee had hunting grounds in the southern part of the ocean.

Europe was still living a peaceful life, but Langsdorff had already been ordered to maintain maximum secrecy of movement, so as not to alarm the British ahead of time. "Spee" managed to sneak unnoticed, first to the shores of Norway, and then to enter the Atlantic south of Iceland. This route, subsequently carefully guarded by British patrols, would not be repeated by any German raider. Bad weather helped the German ship continue to remain undetected. On September 1, 1939, the “pocket battleship” was found 1000 miles north of the Cape Verde Islands. A meeting with Altmark was scheduled and took place there. Langsdorff was unpleasantly surprised that the supply team discovered and identified the German raider by its high tower-like superstructure, which had no analogues on other ships. Moreover, the Altmark itself was spotted from the Spee later. Having taken fuel and completed the supply team with artillery servants, Langsdorff continued sailing south, maintaining complete radio silence. "Spee" maintained complete secrecy, dodging any smoke - Hitler still hoped to resolve the issue with Poland in the style of "Munich 2.0" and therefore did not want to anger the British ahead of time. While the “pocket battleship” was waiting for instructions from Berlin, its team, taking into account the opinion of colleagues from the “Altmark”, began camouflaging the ship. A second one was installed from plywood and canvas behind the front main caliber turret, which gave the Spee a vague resemblance to the battle cruiser Scharnhorst. One could expect that a similar trick would work with captains of civilian ships. Finally, on September 25, Langsdorff received freedom of action - an order came from headquarters. The hunter could now shoot game, and not just watch it from the bushes. The supply worker was released, and the raider began patrolling the northeastern coast of Brazil near the port of Recife. On September 28, we were lucky for the first time - after a short pursuit, the British 5,000-ton steamer Clement, which was carrying out a coastal voyage from Pernambuco to Bahia, was stopped. When trying to send their first prey to the bottom, the Germans had to work hard: despite the explosive cartridges and open seams, the ship did not sink. Two torpedoes fired at it missed. Then the 150-mm guns were used and, wasting precious shells, the obstinate Englishman was finally sent to the bottom. The war was just beginning, and both sides had not yet accumulated merciless bitterness. Langsdorf contacted the coastal radio station and indicated the coordinates of the boats in which the Clement crew members were located. However, this not only revealed the location of the raider, but also helped the enemy identify him. The fact that a powerful German warship, and not a poorly armed “trader,” was operating in the Atlantic alarmed the British command, and it promptly responded to the threat. To search and destroy the German “pocket battleship”, 8 tactical battle groups were created, which included 3 battle cruisers (British “Rinaun” and French “Dunkirk” and “Strasbourg”), 3 aircraft carriers, 9 heavy and 5 light cruisers, not counting ships involved in escorting Atlantic convoys. However, in the waters where Langsdorff was going to work, that is, in the South Atlantic, all three groups opposed him. Two of them did not pose an excessive threat and consisted of a total of 4 heavy cruisers. A meeting with Group K, which included the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and the battlecruiser Rhinaun, could have been deadly.

Spee captured her second trophy, the British steamer Newton Beach, on the Cape Town-Freetown line on October 5. Along with the maize cargo, the Germans received an intact English ship's radio station with the corresponding documentation. On October 7, the Ashley steamship, transporting raw sugar, became a victim of the raider. Allied ships were actively searching for the robber who dared to venture into the Atlantic, into this “old English court.” On October 9, an aircraft from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal discovered a large tanker lying adrift west of the Cape Verde Islands, which called itself the American transport Delmar. Since no one was escorting the aircraft carrier except the Rinaun, Admiral Wells decided not to conduct an inspection and follow the previous course. Thus, the supply ship Altmark avoided the fate of being destroyed at the very beginning of its voyage. Out of harm's way, transport moved to southern latitudes. On October 10, the “pocket battleship” stopped the large transport Huntsman, which was carrying various food cargo. Having sunk it, the Spee on October 14 met with the almost exposed Altmark, to which it transferred prisoners and food from captured English ships. Having replenished fuel reserves, Langsdorff continued the operation - on October 22, the raider stopped and sank an 8,000-ton ore carrier, which, however, managed to transmit a distress signal, which was received on shore. Fearing being discovered, Langsdorff decided to change his area of activity and try his luck in the Indian Ocean. For the first time since the beginning of the campaign, having contacted headquarters in Berlin and saying that it plans to continue the campaign until January 1940, on November 4, the Spee rounds the Cape of Good Hope. He moved towards Madagascar, where major ocean shipping routes intersected. On November 9, when landing in rough sea conditions, the ship's Ar-196 reconnaissance aircraft was damaged, which left the “pocket battleship” without eyes for a long time. The expectation of rich loot that the Germans were counting on did not materialize - only on November 14, the small motor ship Africa Shell was stopped and scuttled.

On November 20, Admiral Graf Spee returned to the Atlantic. November 28 - a new rendezvous with the Altmark, which was pleasant for the crew exhausted by the fruitless campaign, from which they took fuel and updated the stock of provisions. Langsdorff decided to return to the successful waters for his ship between Freetown and Rio de Janeiro. Having replenished its supplies, the ship could now continue cruising until the end of February 1940. Its engines were rebuilt, and aircraft mechanics were finally able to bring the reconnaissance aircraft back to life. Things went more smoothly with the flying Arado - on December 2, the Doric Star turbo ship with a load of wool and frozen meat was sunk, and on December 3, the 8,000-ton Tairoa, which was also transporting lamb in refrigerators. Langsdorff again decides to change the cruising area, choosing for this the mouth of the La Plata River. Buenos Aires is one of the largest ports in South America, and several English ships visited almost daily. On December 6, the Admiral Graf Spee meets with its supply officer Altmark for the last time. Taking advantage of the opportunity, the “pocket battleship” conducts artillery exercises, choosing its own tanker as a target. Their result extremely disturbed the senior gunner of the ship, frigate captain Asher - the fire control system personnel showed a very mediocre level of equipment proficiency during two months of inactivity. On December 7, taking away more than 400 prisoners, Altmark parted with its charge forever. By the evening of the same December 7, the Germans managed to capture their last trophy - the steamship "Streonshel", loaded with wheat. The newspapers found on board contained a photograph of the British heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland in camouflage. It was decided to make up like him. The Spee is repainted and a fake smokestack is installed on it. Langsdorff planned to return to Germany after piracy off La Plata. However, history turned out differently.

Commodore Harewood's British cruiser Force G, like persistent hunting dogs on the trail of a wolf, had long been plying the South Atlantic. In addition to the heavy cruiser Exeter, the commodore could count on two light cruisers - Ajax (New Zealand Navy) and the same type Achilles. The patrol conditions of Harewood's group were probably the most difficult - the nearest British base of Port Stanley was more than 1000 miles from the area of operation of his formation. Having received a message about the death of the Doric Star off the coast of Angola, Harewood logically calculated that the German raider would rush from the coast of Africa to South America to the most “grainful” area for production - at the mouth of La Plata. With his subordinates, he had long ago developed a battle plan in case of a meeting with a “pocket battleship” - to persistently close in order to make the most of the numerous 6-inch artillery of light cruisers. On the morning of December 12, all three cruisers were already off the coast of Uruguay (Exeter was hastily called from Port Stanley, where it was undergoing maintenance).

“Spee” was also moving towards approximately the same area. On December 11, his on-board plane was completely disabled during landing, which may have played an important role in the events that occurred later.

Wolf and hounds. Battle of La Plata

At 5.52, observers from the tower reported that they could see the tops of the masts, and Langsdorff immediately gave the order to go full speed. He and his officers believed that it was some kind of “merchant” hurrying to the port, and went to intercept it. However, the approaching ship with the Spee was quickly identified as an Exeter-class heavy cruiser. At 6.16 "Exeter" signaled to the flagship "Ajax" that the unknown person looked like a "pocket battleship". Langsdorff decides to take the fight. The ammunition load was almost full, and one “Washington tin” was a weak threat to the “pocket battleship”. However, two more smaller enemy ships were soon discovered. These were the light cruisers Ajax and Achilles, mistaken by the Germans for destroyers. Langsdorff's decision to take the battle was strengthened - he mistook the cruiser and destroyers for guarding a convoy that should be nearby. The defeat of the convoy was supposed to successfully crown the modestly effective voyage of the Spee.

At 6.18, the German raider opened fire, firing at the Exeter with its main caliber. At 6.20 the British heavy cruiser returned fire. Initially, Langsdorff gives the order to concentrate fire on the largest English ship, providing "destroyers" for auxiliary artillery. It should be noted that in addition to standard fire control devices, the Germans also had at their disposal the FuMO-22 radar, capable of operating at a distance of up to 14 km. However, during the battle the Spee gunners relied more on their excellent rangefinders. The overall ratio of artillery of the main calibers: six 280 mm and eight 150 mm guns on the “pocket battleship” versus six 203 and sixteen 152 mm on three English ships.

"Exeter" gradually reduced the distance and hit the "Spee" with its fifth salvo - a 203-mm shell pierced the 105-mm installation on the starboard side and exploded inside the raider's hull. The German response was significant, the eighth salvo of the “pocket battleship” smashed turret “B” on the “Exeter”, a barrage of shrapnel riddled the bridge, wounding the ship’s commander, Captain 1st Rank Bell. More hits followed, knocking out the steering and causing further damage. Settled on his nose and shrouded in smoke, the Briton slows down his rate of fire. Until this time, he had managed to achieve three hits in the Spee: the most sensitive was in its control and rangefinder post. At this time, both light cruisers crept up to the “pocket battleship” at 12 thousand meters, and their artillery began to damage the lightly armored superstructures of the raider. It was because of their persistence that at 6.30 Langsdorff was forced to transfer the fire of the main caliber artillery to these two “impudent people,” as the Germans themselves later said. Exeter fires torpedoes, but Spee easily avoids them. The commander of the German ship ordered to increase the distance to 15 km, leveling the already very annoying fire of Ajax and Achilles. At 6.38, another German shell disabled turret “A” on the Exeter, and now it is increasing the distance. His companions rush at the raider again, and the heavy cruiser gets a break. It is in a deplorable state - even the Ajax ship's plane, which tried to adjust the fire, reported to Harewood that the cruiser was burning and sinking. At 7.29 Exeter left the battle.

Now the battle turned into an unequal duel between two light cruisers and a “pocket battleship”. The British constantly maneuvered, changed course, throwing off the German artillerymen's aim. Although their 152 mm shells could not sink the Spee, their explosions destroyed the unprotected superstructure of the German ship. At 7.17, Langsdorff, who commanded the battle from the open bridge, was wounded - shrapnel cut his hand and shoulder and hit him so hard on the bridge that he temporarily lost consciousness. At 7.25, both aft turrets of the Ajax were disabled by a well-aimed hit from a 280-mm shell. However, the light cruisers did not stop firing, achieving a total of 17 hits on the Admiral Graf Spee. Losses in its crew amounted to 39 people killed and 56 wounded. At 7.34 a new German shell demolished the top of the Ajax mast with all the antennas. Harewood decided to end the battle at this stage - all his ships were heavily damaged. Regardless of his English opponent, Langsdorff came to the same conclusion - reports from combat posts were disappointing, water was observed entering the hull through holes at the waterline. The speed had to be reduced to 22 knots. The British put up a smoke screen and the opponents disperse. By 7.46 the battle ends. The British suffered much more severely - Exeter alone lost 60 people killed. There were 11 dead among the light cruiser crews.

Not an easy decision

The end of the German raider. "Spee" was blown up by the crew and is on fire

The German commander was faced with a difficult task: wait until nightfall and try to escape with at least two enemies on his tail, or go to a neutral port for repairs. A torpedo specialist, Langsdorf fears night torpedo attacks and decides to go to Montevideo. On the afternoon of December 13, the Admiral Graf Spee enters the roadstead of the capital of Uruguay. "Ajax" and "Achilles" guard their enemy in neutral waters. An examination of the ship gives conflicting results: on the one hand, the battered raider did not receive a single fatal injury, on the other, the total amount of damage and destruction raised doubts about the possibility of crossing the Atlantic. There were several dozen English ships in Montevideo; the nearest ones were constantly monitoring the actions of the Germans. The British Consulate skillfully spreads rumors that the arrival of two large ships is expected, by which the Ark Royal and Rinaun are clearly meant. In fact, the “enlightened sailors” were bluffing. On the evening of December 14, the heavy cruiser Cumberland joined Harewood instead of the Exeter, which had gone for repairs. Langsdorff is conducting difficult negotiations with Berlin regarding the future fate of the crew and the ship: to be interned in Argentina, loyal to Germany, or to sink the ship. For some reason, the option of a breakthrough is not being considered, although Spee had every chance of doing so. In the end, the fate of the German ship was decided directly by Hitler in a difficult conversation with Grand Admiral Raeder. On the evening of December 16, Langsdorff receives orders to scuttle the ship. On the morning of December 17, the Germans begin to destroy all valuable equipment on the “pocket battleship”. All documentation is burned. By evening, work to prepare for self-destruction was completed: the bulk of the crew was transferred to the German ship Tacoma. At about 18 o'clock the flags were raised on the masts of the “pocket battleship”, it moved away from the pier and began to slowly move along the fairway in a northerly direction. This action was watched by a crowd of at least 200 thousand people. Having moved 4 miles from the shore, the raider dropped anchor. At about 20 o'clock there were 6 explosions - the ship sank to the bottom and fires started on it. Explosions were heard on the shore for another three days. The crew, with the exception of the wounded, reached Buenos Aires safely. Here Langsdorff addressed the team for the last time, thanking them for their service. On December 20, he shot himself in a hotel room. The voyage of the “pocket battleship” was completed.

Ship wreck

A mocking fate would have it that the ship “Admiral Count Spee”, a quarter of a century later, would rest on the ocean floor just a thousand miles from the grave of the man after whom it was named.

The effectiveness of smart PR

The report of what had happened caused a slight panic in the Admiralty. The command understood that if the “predator healed its wounds” and went to sea, both English ships would be destroyed. It was necessary at all costs to detain “...Spee” in the port until reinforcements arrived, and it would be even better to intern him, that is, according to wartime laws, deprive him of freedom of movement and exit from the country until the end of hostilities. It seemed impossible to achieve this, but lacking power, the British resorted to what we call “PR” - controlling consciousness with the help of information. It was necessary to convince the highest naval ranks of Germany, on whom the further development of events depended, of the need to take the measures necessary for the Admiralty, and to do this in such a way that they considered it their own decision.

Additional bibliography

- Aguiar Godinho Carlos, Mayor: Anecdotes from the Mission (Guardianship of the German Marines Graf Spee and Tacoma)

. Ed., Military Center, Montevideo (Uruguay), 2002. - Almeida, Roni: The Story of the Pocket Battleship Almirante Graf Spee (or the Truth about the Naval Battle at Punta del Este)

. Author's edition, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1977. - British Admiralty: The Battle of the River Plate

. Ed. His Majesty's Stationery Office, London (UK), 1940 - Atwill, RF: Battle of the River Plate, December 1939 - Monograph 105

- Ed. Australian Naval Historical Society, Rooty Hill (Australia), 2001. - Various authors (they did not want the name) - Raider Spee

(private Spee). Ed Minerva, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1949 - Becker, Rolf O.: Auf Kaperfahrt im Atlantik

(Corsair in the Atlantic). Ed Zimermann, Balve EA (Germany), 1960. - Becker, Caius: the struggle and death of the German Navy

(original title "Kampf und Untergang der Kriegsmarine"). Editorial Luis Caralt, Barcelona, 1959 ISBN 84-217-5684-2 - Bennett, Geoffrey: The Battle of the River Plate

. Ed Ian Allan, London (UK), 1972. - Breuer, Siegfried: Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee - Serie Marine Arsenal Nr.

8 . Ed. Podzun Pallas, Friedeberg (Alemannia), 1989 - Breuer, Siegfried: battleships and battlecruisers 1905-1970

. Doubleday & Company, Nueva York, 1973. - Breuer, Siegfried: Die Panzerschiffe der Kriegsmarine, Special Band 2

(pocket battleships of the German Navy). Series “Naval Arsenal” No. 2. Ed. Podzun Pallas, Wölfersheim-Berstadt (Germany), 1995. - Campbell, A.B., Comdr. RD: The Battle of

the Plata (La batalla del Plata). Ed. Herbert Jenkins Ltd., London (Grande Bretagne), 1941 - Campos, Alfredo R., Grl Div Arq.: An Episode of the Second World War in the Territorial Waters of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay

. Military Center Publication, vol. 5 (reprint of the original), Montevideo (Uruguay), 2002. - Darnau, Martin: The Adventure of "Count Spee": The Story of the Battle of the River Plate

. Ed From the New World, Montevideo (Uruguay), 1989. - Dau, Heinrich, captain: Unendeckt über die Meere - Die Fahrt der "Altmark"

("Hidden by the Seas - Voyage on the Altmark").

Die Wehrmacht edition, Berlin (Germany), 1941. There is a Danish version entitled Fra Montevideo til Jössingfjord - Eventyrlige Altmark Togt som Ledsageskib for "Graf Spee" (From Montevideo to Jossingfjord - Altmark's adventurous journey as companion of Count Spee)

from the Martins publishing house , Copenhagen (Denmark), 1944. - Dick, Enrique: In the footsteps of Count Spee

.

Ed. EDIVERN. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. ISBN 987-1084-06-4. English version: In the Wake of the Count Spee

Ed WIT, Southampton (UK), 2015, ISBN 978-1-84564-932-6 - Dove, Patrick: I was a prisoner of Count Spee

. Ed Cherry Tree, Manchester (UK), 1940, and Viking Press, 1956. - Farrell, FL: Surface Raider

. Published by Trojan Publ., London (UK) no year indicated. - Fieber, Johann: The Last Journey and Escape from Internment

(Última travesía y huida de la internación). Ed. Jan and Ernst, Hamburg (Germany), 1986 - Fuchs, Hans: Eine Insel im La Plata

(Island on the Plata). Published by Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg (Germany), 1943. - Gilbey, Joseph: Langsdorff of Count Spee, Prince Emeritus

.

Edition del Autor, Ontario (Canada), 1999. The Argentine edition of Langsdorff del Graf Spee, Príncipe de honor

, was published by Naval Publications in Buenos Aires (Argentina) in 2000, with a second edition in 2006. - Gilbey, Joseph: Kriegsmarine: Admiral Rieder's Fleet

. Author's edition, Ontario (Canada), 2005. - Grove, Eric J.: The Cost of Disobedience

. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland (USA), 2000. - Harmut, Gerhard, Schwalbe, Georg: "Count Spee" at sea (from Kiel to Punta del Este)

. Editorial Haz, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1954. There is a newer edition, without specifying the year, from García Hispan Editores in Granada (Spain) and a more recent edition from Librería Huemul, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 2005. NB: This the book is a version translated by José Novo Cerro from Raider Spee, where the authors have stated that they are not named. - Lanata, Jorge: The Argentines, Volume 2

. Editions B, 2003 ISBN 950-15-2259-8 - Landsborough Gordon: The Battle of the River Plate

. Ed Panther, London (UK), 1956. - Lawrence, Ricardo E.: From Wilhelmshaven to Montevideo. Author's edition, Rosario (Argentina), 1992.

- Lawrence, Ricardo E.: Operativo Graf Spee

, Ed Del Autor, Rosario (Argentina), 1996. - Lawrence, Ricardo E.: The Crew of the Graf Spee in Three Fascinating Stories

. Author's edition, Rosario (Argentina), 2000. - Leicht, Federico: Count of Spee, from Wilhelmshaven to Rio de la Plata

. Plaza Editions, Montevideo (Uruguay), 2009 - Mahlmann Showell, Jak P.: The German Navy in the Second World War

. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1979. ISBN 0-87021-933-2 - Millington-Drake, Sir Eugen: The Drama of Count Spee and the Battle of the River Plate

.

Colombino Hnos (Uruguay), 1965, and Instituto de Publicaciones Navales (Argentina), 1966. Available in English (original) The Drama of Count Spee and the Battle of Plate

, Peter Davies, 1964, and in French language,

La fin de Graf Spee

, Laffont 1968 and J`ai Lu, 1968. - Powell, Michael: Die Schicksalsfahrt der Graf Spee

(The Dramatic Passage through the Graf Spee).

Published by Fackelverlag, Stuttgart (Germany), 1957. Various editions of the original Death in the South Atlantic exist ; The Last Voyage of the "Count of Spee" or

"

The Battle of the River Plate

", London 1956 (Hodder and Stoughton p. 224), 1960, 1973, 1974 and 1975.

The sinking of the Graf Spee), Utrecht, 1962/63, and in French, La bataille du Rio de la Plata

, Ed Presses de la Cité, 309 pp., 1957. - Neumann, Klaus: "Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee" - second edition on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Rio de la Plata. Ed.epubli/Holzbrinck-Verlag, Berlin (Germany), 2022. ISBN 978-3-750208-83-4. The author is the son of a crew member of the Graf Spee, and also created the Panzerschiff documentation "Admiral Graf Spee".

- Rasenak, Friedrich Wilhelm: The Battle of the Rio de la Plata

- ed., Gure, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1957. The original edition,

Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee

, was published in Germany by Heyne in 1956. There are different publications in German. and Spanish for 1957 (Kehlers), 1977, 1981, 1982 (Heyne), 1985, 1989 (Beutelspacher), 1999 and 2000 (Yesterday and Today). - Rüppel, Erich: Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee

- Ed. author, Norderstedt (Germany), 2004 - Schlichter, Andres José, Spinetto, Julio Ricardo: Postal History of the Crew of the Battleship Admiral Graf Spee

. Histpost Editions, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1989. - Sierra, Luis de la: Naval War in the Atlantic (1939-1945)

. Youth, 1974, ISBN 84-261-5715-7. - Strabolgi, Lord, R.N.: The Battle of the Slab

.

Published by Hutchinson & Co., London (UK), 1941. A French version is available entitled La bataille du Rio de la Plata et ses suites: la fin du cuirassé de poche allemand Admiral Graf Spee et l'affaire de l'Altmark dans les eaux norvégiennes

(The Battle of the Rio de la Plata and its aftermath: the end of the German pocket battleship and the Altmark question in Norwegian waters). Payot, 1945. - Wild, Heinrich: Spee was my destiny

(El Spee fue mi destino). Ed. del Author, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1989 - York, Martin: The Sinking of the Graf Spee

(El hundimiento del Graf Spee). Series Combat Library Nr. 26, ed. Publisher GM Smith, Portsmouth (Grande Bretagne), 1960.

Soap operas

- Harding, Duncan: Sink Graf

Spee. Ed. Magna Books Library, Cornwall (Gran Bretagne), 1999 - Grill, Etienne: The Lair of Count Spee

(La guarida del Graf Spee). Published by Collection of Marabou, Paris (France), 1945. - Medina Soca, Omar: Tombs of the Rio de la Plata

. Author's edition, Port of Montevideo (Uruguay), 1969. - Müller, Rudolf (pseudonym of Juan Andrés Cuello Freire): Count of Spee

. Ed Enrique Signoris, Buenos Aires (Argentina), 1954