The last ten years of the Soviet state were marked by the so-called Afghan War of 1979-1989.

In the turbulent nineties, due to vigorous reforms and economic crises, information about the Afghan war was practically crowded out of the collective consciousness. However, in our time, after the colossal work of historians and researchers, after the removal of all ideological stereotypes, an impartial look at the history of those long-ago years has opened up.

Conditions for conflict

On the territory of our country, as well as on the territory of the entire post-Soviet space, the Afghan war can be associated with one ten-year period of time 1979-1989. This was a period when a limited contingent of Soviet troops was present on the territory of Afghanistan. In reality, it was just one of many moments in a long civil conflict.

The prerequisites for its emergence can be considered 1973, when the monarchy was overthrown in this mountainous country. After which power was seized by a short-lived regime headed by Muhammad Daoud. This regime lasted until the Saur revolution in 1978. Following her, power in the country passed to the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, which announced the proclamation of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan.

The organizational structure of the party and state resembled the Marxist one, which naturally brought it closer to the Soviet state. The revolutionaries gave preference to leftist ideology, and of course made it the main one in the entire Afghan state. Following the example of the Soviet Union, they began to build socialism.

Even so, even before 1978, the state already existed in an environment of continuous unrest. The presence of two revolutions and a civil war led to the elimination of stable socio-political life in the entire region.

The socialist-oriented government confronted a wide variety of forces, but radical Islamists played first fiddle. According to Islamists, members of the ruling elite are enemies not only of the entire multinational people of Afghanistan, but also of all Islam. In fact, the new political regime was in a position of declaring a holy war against the “infidels.”

In such conditions, special detachments of Mujahideen warriors were formed. It was these mujahideen that the soldiers of the Soviet army fought against, for whom the Soviet-Afghan War began after some time. In a nutshell, the success of the Mujahideen is explained by the fact that they skillfully carried out propaganda work throughout the country.

The task of the Islamist agitators was made easier by the fact that the vast majority of Afghans, approximately 90% of the country's population, were illiterate. On the territory of the country, immediately upon leaving large cities, a tribal system of relations with extreme patriarchy reigned.

Maps of Afghanistan

Maps of Afghanistan,Index map for 1280x1024 resolution

https://kunar.artofwar.ru/maps/200k/html/index.html

Index map for 800x600 resolution

https://kunar.artofwar.ru/maps/200k/html/index800.html

Small instructions for downloading. 1. Load an indexed map (for a resolution of 1280x1024 or 800x600) 2. Determine which square you are interested in. For example, I served in square I-42-12. 3. Click on the card number (in my case it is I-42-12). 4. In a new window you will see a small map of the required square. 5. If you want to view a full-size map, simply click on it with the left mouse button. 6. If you want to download the map, right-click on it and select “Save target as” from the menu that appears.

Material provided by Yuri Khristensen

ACCORDING TO EXACT DIRECTIONS, THE AFGHAN DUSHMANS WERE LOOKING FOR ANY OPPORTUNITY TO OBTAIN SOVIET MAPS

Every second Sunday in March, this year it falls on the 8th, workers of geodesy and cartography in Russia celebrate their professional holiday. And since a short period separates this day from another memorable date - the 20th anniversary of the withdrawal of the Limited contingent of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, we offer an interview with the former head of the topographic service of the 40th combined arms army, Boris Pavlov.

— Boris Nikitich, what tasks did the topographic service of the 40th Army face when supporting combat operations in Afghanistan? — There were many tasks: operational provision of formations, units and individual subunits with maps, topographic and geodetic reconnaissance, production of terrain models for command and control agencies and interaction at all levels in the preparation and planning of operations, topographical training of troops. One of the main tasks of the topographic service was to provide maps of military operations of troops on the territory of Afghanistan and create reserves of maps for the planned directions of the theater of military operations. At the initial stage, the troops did not have large-scale maps of the entire territory of this country. The largest was a map at a scale of 1:200,000 - for conducting reconnaissance and organizing road marches, but it did not display specific objects, did not have precise landmarks, and therefore did not allow solving many problems in the interests of the troops. Therefore, initially in 1982-1983, they began to urgently make maps at a scale of 1:100,000, and then, based on them, satellite images and the results of topographic and geodetic reconnaissance, from 1983-1984 they began to create maps at a scale of 1:50,000 for work in the most operationally important areas Afghanistan, which already made it possible to fire artillery at target coordinates. Then there was a build-up of “fifty” maps: with changes in the situation as a result of military operations, with the clarification of some natural features, operational corrections were made to them. And when we covered the entire area of Afghanistan with maps at a scale of 1:50,000, due to this we created special maps of geodetic data. This is how a geodetic basis appeared - the exact coordinates of some objects, points, so necessary for firing missile troops and artillery, for linking military formations of troops to the terrain. By 1985, the troops of the 40th Army were provided with maps of a scale of 1:100,000 by 70-75 percent, by 1986 - by almost all 100. And with maps of a scale of 1:50,000 they were fully provided somewhere by 1986-1987 . — How was topographical reconnaissance carried out? — Topographers from all formations and units of the 40th Army were involved in conducting topographic reconnaissance of the area during the movement of troops and during combat operations. Probably 60 percent of all topographic reconnaissance relied on aerial photography. Especially before major military operations. There was a squadron of aircraft near Kabul, among them an An-30 aircraft with equipment for aerial photography - it flew to the most important areas. In this case, the photography was carried out by the pilots themselves, since they were more prepared to work with this equipment, and the topographers who flew out with them only clarified the task for them. The aviators had their own photo laboratory, and when we then processed the captured information on the ground together with them, such work brought good results. Although the An-30 flew under the cover of helicopters, conducting topographic reconnaissance from the air was still a rather risky activity - these planes could be shot down at any moment. But, thank God, this never happened. On earth, all the necessary information was collected through natural, everyday observations. The specificity of Afghanistan was that no one sent any special topographic and geodetic expeditions anywhere; topographers moved throughout the entire territory only as part of troops during certain operations. Everything was noticed. For example, convoys, as a rule, were driven by army, division, and brigade topographers, and before each march they reminded the drivers and vehicle leaders: “Guys, if you see something suspicious somewhere, report it immediately.” What was noticed? Where previously there was no vegetation, a bush suddenly appeared - which means this is a landmark for someone. A triangle of stones appeared near the road, clearly laid out by human hands - also a landmark. Intelligence units and special forces also gave us similar information. Subsequently, after topographers determined the coordinates of the discovered landmarks, the artillerymen fired harassing fire there, and sometimes this was effective. All the topographic information obtained flowed to the heads of topographic services of divisions and brigades, and from them to me, the head of the topographic service of the 40th Army. We summarized this information and transferred it to the topographic service of the Turkestan Military District, which at that time was working on a wartime basis - the number of officers was increased. From there, information for further processing was distributed to the topographic and geodetic detachments of the Topographic Service of the USSR Armed Forces, which had to make appropriate corrections to the maps within the specified time frame. Four topographic and geodetic detachments of central subordination worked simultaneously under stationary conditions - Noginsky, Golitsynsky, Irkutsk, Ivanovo and the Tashkent Cartographic Factory. In addition to them, each military district had two or three field topographic and geodetic detachments, which were also engaged in the prompt correction of maps. Each of the detachments worked over a specific region of Afghanistan according to the orders of the Military Topographical Directorate of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces. The already corrected and supplemented maps were again received by our topographic service, which was stationed in the outskirts of Kabul near the headquarters of the 40th Army, in the Darulaman area. The sorting soldiers of the army topographic unit, which was located there, quickly collected these maps, loaded them into special AShT vehicles (army headquarters topographic vehicle based on ZIL-131) and transported them piece by piece. When it was necessary to deliver maps more quickly, we were assigned helicopters. For inserts from personal files

|

Requests from the ruling regime of Afghanistan for Soviet military assistance

Before the revolutionary government that had come to power had time to properly establish itself in the capital of the state, Kabul, an armed uprising, fueled by Islamist agitators, began in almost all provinces.

In such a sharply complicated situation, in March 1979, the Afghan government received its first appeal to the Soviet leadership with a request for military assistance. Subsequently, such appeals were repeated several times. There was nowhere else to look for support for the Marxists, who were surrounded by nationalists and Islamists.

For the first time, the problem of providing assistance to Kabul “comrades” was considered by the Soviet leadership in March 1979. At that time, General Secretary Brezhnev had to speak out and prohibit armed intervention. However, over time, the operational situation near the Soviet borders deteriorated more and more.

Little by little, the members of the Politburo and other senior government functionaries changed their point of view. In particular, there were statements from Defense Minister Ustinov that the unstable situation on the Soviet-Afghan border could prove dangerous for the Soviet state.

Thus, already in September 1979, regular upheavals occurred on the territory of Afghanistan. Now there has been a change of leadership in the local ruling party. As a result, party and state administration fell into the hands of Hafizullah Amin.

The KGB reported that the new leader had been recruited by CIA agents. The presence of these reports increasingly inclined the Kremlin to military intervention. At the same time, preparations began for the overthrow of the new regime.

The Soviet Union leaned towards a more loyal figure in the Afghan government - Barak Karmal. He was one of the members of the ruling party. Initially, he held important positions in the party leadership and was a member of the Revolutionary Council. When the party purges began, he was sent as ambassador to Czechoslovakia. He was later declared a traitor and conspirator. Karmal, who was then in exile, had to stay abroad. However, he managed to move to the territory of the Soviet Union and become the person who was elected by the Soviet leadership.

Beginning of the war in Afghanistan

In the sixties, in the kingdom of Afghanistan - an extremely backward semi-feudal country - a communist party was created under the leadership of Nur Muhammad Taraki.

In 1967, this party split into two parts; Khalq (People) and Parcham (Banner). The pro-Soviet Parcham faction was led by the son of the royal army general Babrak Karmal. On June 17, 1973, the king's cousin, Mohammed Daoud Khan, carried out a coup d'état and abolished the monarchy. Five years later, both factions of the Communist Party united into the Democratic People's Party of Afghanistan (DPPA) and carried out a new coup on April 27, 1978. Daoud and 30 members of his family were executed. Taraki became the president of the country, Karmal became the vice-president.

That same year, both factions of the DNPA split again. Taraki proclaimed a course to transform Afghanistan into a modern socialist state. He turned to the USSR for economic and financial assistance, from where thousands of advisers came. With their help, Taraki tried to implement land, social and educational reforms. However, this turned out to be a utopia. Neither the Khalq faction nor the Parchami faction succeeded in extending their influence to the fanatically religious Muslims. DNPA members, together with their sympathizers, made up less than half of one percent of the country's population. Basically, they were officers, officials, and intellectuals.

In April 1979, a year after the April “revolution” of 1978, an uprising against the communist regime began simultaneously in all provinces of Afghanistan. Very soon, only the cities remained under the control of the 90,000-strong government army. The rebels dominated the countryside, especially at night.

In May 1979, Hafizullah Amin became prime minister. He began to brutally suppress the uprising. All prisons were overcrowded, executions were carried out daily. But in response to the repressions, the popular resistance movement spread both in breadth and depth, covering more and more new areas of the country and more and more new social groups. No one in the West was concerned about the events in Afghanistan then, because traditionally this state was in the sphere of geopolitical influence of the USSR. But the Soviet leadership was extremely concerned about the threat of the imminent fall of the communist government in Kabul. It feared that as a result of the victory of Islamic fundamentalists, unrest could begin among the Muslim population of the Asian Soviet republics - Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan.

The first reaction of the Soviet leadership was to send several hundred military advisers to Afghanistan. At the same time, it invited Taraki to remove Amin, hated by the people, and stop mass repressions. However, Amin responded to the changing situation faster. On September 14, 1979, his associates captured the presidential palace. Taraki was seriously injured during the assault and died three days later. Executions and executions of the dissatisfied became even more widespread. People were now being destroyed in entire villages. It was clear that Amin's regime was doomed.

On December 2 of the same year, KGB Lieutenant General Viktor Paputin arrived in Kabul on a delicate mission. He had to try to persuade Amin to voluntarily cede power to Babrak Karmal, who by that time had already been deprived of the post of vice president and was working as ambassador to Czechoslovakia. Amin categorically refused to do this. A similar option was envisaged. Moreover, regardless of the dictator’s consent or disagreement to resign, in any case it was considered necessary to introduce Soviet troops into Afghanistan, who could with their might support the government army in its fight against the rebels. Therefore, Paputin began to convince Amin to turn to the USSR with an official request to send troops. Amin did not object to military assistance, but did not want to publicly ask for it from his powerful northern neighbor.

On December 25, 1979, Il-76, An-22 and An-12 transport aircraft began landing at Bagram airbase, 50 km north of Kabul.

with personnel and armored vehicles of the 105th Guards Airborne Division. The landing lasted three days. Meanwhile, Amin, extremely concerned about his safety, took refuge in the suburbs of the capital, in the well-fortified Dar-ul-Aman Palace (or Taj Beg). Paputin arrived there and once again tried to persuade Amin to resign, and before that to publish a request for Soviet military assistance. The conversation took a sharp turn and Amin’s bodyguard shot Paputin.

There was nothing left but to remove Amin by force. On the evening of December 27, a KGB special group of 50 people broke into the palace and killed Amin. At the same time, other special groups, together with people from the Parcham faction, killed or took into custody high-ranking officers and officials of the Amin regime. And units of the 105th Airborne Division entered Kabul and occupied all strategically important points. Having received a signal about the beginning of a coup in Kabul, the 40th Army invaded Afghanistan. Its 66th and 357th motorized rifle divisions set out from Kushka to Herat and further through Farah to Lashkargan. The 201st and 360th divisions from Termez marched to Mazar-i-Sharif, and then south to the strategically important tunnel at the Salang Pass, and also east to the city of Faizabad. In many places, Afghan troops tried to resist, but they were outnumbered for a long time. In the area of the city of Kandahar, both columns of Soviet troops closed the ring (see diagram).

Babrak Karmal became the President of Afghanistan. He released almost all political prisoners, rehabilitated the victims of Amin's terror, and carried out reforms more gently. However, the people considered him a simple puppet in the hands of the “shuravi” (Soviet instructors and commanders). The guerrilla war, which initially subsided for some time, gradually flared up with renewed vigor. Government troops, police (Tsaranda) and state security agencies (Khad) waged a fierce fight against them. Soviet units controlled cities, air bases, the most important industrial enterprises and roads.

By February 1980, the number of “limited contingent” reached 85 thousand people, and by the beginning of 1984 - 135 thousand. In mid-1985, the total number of Soviet troops in Afghanistan was already 150 thousand people. Of these, about 75% belonged to combat units, and 25% to logistics units and military instructors in the Afghan army. In addition, in the Turkestan Military District there was a reserve of approximately 50 thousand military personnel, through which the losses in killed, wounded, prisoners, deserters were made up and soldiers transferred to the reserve were replaced. It was not possible to increase the group beyond 150 thousand due to difficulties in supplying it. The road network in Afghanistan is poorly developed, in addition, stretched communications were constantly subject to guerrilla attacks. Suffice it to say that over 9 years (January 1980 - January 1989) they destroyed about 12 thousand trucks and tankers, more than a thousand armored personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles on the roads.

The Soviet contingent in Afghanistan consisted of the 8th motorized rifle divisions, the 105th (Vienna) airborne, two or three regiments of the 103rd (Vitebsk) airborne division, two special forces brigades and two border troops units. Due to the withdrawal of tank and missile regiments, all motorized rifle divisions were not fully equipped. Seven out of eight motorized rifle divisions were located along the Afghan ring road Kushka - Herat - Kandahar - Ghazni - Kabul - Mazar-i-Sharif - Termez. At the air bases of Bagram, Shindand and others (12 airfields in total) there were 2 aviation divisions (270 combat aircraft) and 4 regiments of combat helicopters (about 250 Mi-8 and Mi-24 vehicles). They were supported by 2 more air divisions from the airfields of the Turkestan and Central Asian military districts. In addition to combat ones, Soviet troops had approximately 350 transport helicopters in Afghanistan.

The Afghan army, which initially numbered 90 thousand people, was reduced by more than half in 5 years as a result of heavy losses and mass desertion (up to 20 thousand per year). By 1986, it consisted of about 40 thousand people in the ground forces and 7 thousand in aviation (150 combat aircraft and 30 combat helicopters). True, to them we must add 30 thousand police officers, 35 thousand Khad (GB) employees, several thousand border guards (5 brigades) and commandos (4 brigades).

The Afghan army consisted of 11 infantry, 3 tank and 2 motorized rifle divisions, united into 3 corps (Kabul, Kandahar and Gardez).

Due to the large shortage of personnel, the divisions of government troops were actually brigades, each with approximately 2,500 people. The government tried to expand the army by extending service periods, lowering the conscription age to 16, and forced mobilization, but without much success. The level of professional training of Afghan officers was low; they were unable to conduct independent operations against the partisans (without the help of Soviet instructors and the support of Soviet troops). There was a great shortage of non-commissioned officers in the army, as well as specialists who could competently wield modern weapons. Most of the Afghan officers belonged to the Khalq faction. Therefore, the strengthening of the Parcham faction displeased them. Some even went over to the rebel side. Doubts about the reliability of pilots led to the fact that Soviet officers most often flew Afghan planes and helicopters as pilots. In short, the further we went, the more the main burden of the fight against the rebels fell on the shoulders of the Soviet army.

Thus, unexpectedly for itself, the Soviet military and political leadership was faced with the problem of guerrilla warfare. As everyone knows, it was not able to solve this problem. On the contrary, it was the Afghan war that became the catalyst that accelerated and deepened the economic and then political crisis in the USSR, which ended with the collapse of the huge state into 15 independent republics.

How the decision to send troops was made

In December 1979, it became abundantly clear that the Soviet Union might be drawn into its own Soviet-Afghan war. After short discussions and clarification of the last reservations in the documentation, the Kremlin approved a special operation to overthrow the Amin regime.

It is clear that at that moment it is unlikely that anyone in Moscow understood how long this military operation would last. However, even then, there were people who opposed the decision to send troops. These were the Chief of the General Staff Ogarkov and the Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers Kosygin. For the latter, this conviction became another and decisive pretext for an irrevocable severance of relations with General Secretary Brezhnev and his entourage.

They preferred to begin the final preparatory measures for the direct transfer of Soviet troops to the territory of Afghanistan over the next day, namely December 13. The Soviet special services attempted to organize an assassination attempt on the Afghan leader, but as it turned out, this had no effect on Hafizullah Amin. The success of the special operation was in jeopardy. Despite everything, preparatory measures for the special operation continued.

103rd Airborne Division

The Airborne Forces of the Soviet Union included the 350th Afghan Regiment, which was raised on combat alert. He was at the Bykhov airfield, preparing for a combat operation and landing. In December, while landing at an airfield in Kabul, a collision occurred with the Hindu Kush ridge, which resulted in the death of seven crew members and 34 paratroopers.

1979 - the regiment was responsible for carrying out Operation Baikal-79, which involved the capture of seventeen objects. The unit took part in many military operations; for the successful completion of tasks it was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

How the palace of Hafizullah Amin was stormed

They decided to send in troops at the end of December, and this happened on the 25th. A couple of days later, while in the palace, the Afghan leader Amin felt ill and fainted. The same situation happened with some of his close associates. The reason for this was a general poisoning organized by Soviet agents who took over the residence as cooks. Not knowing the true causes of the illness and not trusting anyone, Amin turned to Soviet doctors. Arriving from the Soviet embassy in Kabul, they immediately began providing medical assistance, however, the president’s bodyguards became worried.

In the evening, at about seven o'clock, near the presidential palace, a car stalled near a Soviet sabotage group. However, it stalled in a good place. This happened near the communication well. This well was connected to the distribution center of all Kabul communications. The object was quickly mined, and after some time there was a deafening explosion that was heard even in Kabul. As a result of the sabotage, the capital was left without power supply.

This explosion was the signal for the beginning of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989). Quickly assessing the situation, the commander of the special operation, Colonel Boyarintsev, gave the order to begin the assault on the presidential palace. When the Afghan leader was informed of an attack by unknown armed men, he ordered his associates to request help from the Soviet embassy.

From a formal point of view, both states remained on friendly terms. When Amin learned from the report that his palace was being stormed by Soviet special forces, he refused to believe it. There is no reliable information about the circumstances of Amin’s death. Many eyewitnesses later claimed that he could have lost his life by suicide. And even before the moment when Soviet special forces burst into his apartment.

Be that as it may, the special operation was carried out successfully. They captured not only the presidential residence, but the entire capital, and on the night of December 28, Karmal was brought to Kabul, who was declared president. On the Soviet side, as a result of the assault, 20 people (representatives of paratroopers and special forces), including the commander of the assault, Grigory Boyarintsev, were killed. In 1980, he was posthumously nominated for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Chronicle of the Afghan War

Based on the nature of combat operations and strategic objectives, the brief history of the Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989) can be divided into four main periods.

The first period was the winter of 1979-1980. The beginning of the entry of Soviet troops into the country. Military personnel were sent to capture garrisons and important infrastructure facilities.

The second period (1980-1985) is the most active. The fighting spread throughout the country. They were of an offensive nature. The Mujahideen were being eliminated and the local army was being improved.

The third period (1985-1987) - military operations were carried out mainly by Soviet aviation and artillery. Ground forces were practically not involved.

The fourth period (1987-1989) is the last. The Soviet troops were preparing for their withdrawal. No one has ever stopped the civil war in the country. The Islamists were also unable to be defeated. The withdrawal of troops was planned due to the economic crisis in the USSR, as well as due to a change in political course.

The war continues

State leaders argued for the introduction of Soviet troops into Afghanistan by the fact that they were only providing assistance to the friendly Afghan people, and at the request of their government. Following the introduction of Soviet troops into the DRA, the UN Security Council was quickly convened. An anti-Soviet resolution prepared by the United States was presented there. However, the resolution was not supported.

The American government, although not directly involved in the conflict, was actively financing the Mujahideen. The Islamists possessed weapons purchased from Western countries. As a result, the actual cold war between the two political systems acquired the opening of a new front, which turned out to be Afghan territory. The conduct of hostilities was at times covered by all the world media, which told the whole truth about the Afghan war.

American intelligence agencies, in particular the CIA, organized several training camps in neighboring Pakistan. They trained Afghan mujahideen, also called dushmans. Islamic fundamentalists, in addition to generous American financial flows, were supported by money from drug trafficking. Actually, in the 80s, Afghanistan led the world market for the production of opium and heroin. Often, Soviet soldiers of the Afghan War liquidated precisely such industries in their special operations.

As a result of the Soviet invasion (1979-1989), confrontation began among the majority of the country's population, which had never before held weapons in their hands. Recruitment into the Dushman detachments was carried out by a very wide network of agents spread throughout the country. The advantage of the Mujahideen was that they did not have any single center of resistance. Throughout the Soviet-Afghan War these were numerous heterogeneous groups. They were led by field commanders, but no “leaders” stood out among them.

Many raids did not produce the desired results due to the effective work of local propagandists with the local population. The Afghan majority (especially the provincial patriarchal one) did not accept the Soviet military personnel; they were ordinary occupiers for them.

201st Motorized Rifle Division

It included the 191st Regiment of the Order of A. Nevsky. The personnel numbered more than 2000 people, the location was 60 km from the city of Gardez. The regiment was a large formation that took part in military battles and controlled the transport route from Kabul to Kandahar. Later the unit was responsible for guarding the military camp. The unit took part in a major battle near Kabul.

While in Ghazni, the formation took part in hostilities, the purpose of which was to destroy the Mujahideen.

"Politics of National Reconciliation"

Since 1987, they began to implement the so-called “policy of national reconciliation”. The ruling party decided to give up its monopoly on power. A law was passed allowing “oppositionists” to form their own parties. The country adopted a new Constitution and also elected a new president, Mohammed Najibullah. It was assumed that such events were supposed to end the confrontation through compromises.

Along with this, the Soviet leadership in the person of Mikhail Gorbachev set a course to reduce its weapons. These plans also included the withdrawal of troops from the neighboring state. The Soviet-Afghan war could not be waged in a situation when an economic crisis began in the USSR. Moreover, the Cold War was also coming to an end. The Soviet Union and the United States began negotiating and signing many documents related to disarmament and ending the Cold War.

How Soviet troops were withdrawn

The first time General Secretary Gorbachev announced the upcoming withdrawal of troops was in December 1987, when he officially visited the United States. Following this, the Soviet, American and Afghan delegations managed to sit down at the negotiating table on neutral territory in Switzerland. As a result, the corresponding documents were signed. Thus ended the story of another war. Based on the Geneva agreements, the Soviet leadership promised to withdraw its troops, and the American leadership promised to stop funding the Mujahideen.

Most of the limited Soviet military contingent has left the country since August 1988. Then they began to leave military garrisons from some cities and settlements. The last Soviet soldier to leave Afghanistan on February 15, 1989 was General Gromov. Footage of how Soviet soldiers of the Afghan War crossed the Friendship Bridge across the Amu Darya River flew all over the world.

Echoes of the Afghan War: losses

Many events of the Soviet era were assessed one-sidedly taking into account party ideology, the same applies to the Soviet-Afghan War. Sometimes dry reports appeared in the press, and heroes of the Afghan War were shown on central television. However, before Perestroika and glasnost, the Soviet leadership remained silent about the true scale of combat losses. While the soldiers of the Afghan war in zinc coffins returned home in semi-secrecy. Their funerals took place behind the scenes, and the monuments to the Afghan War were without mention of the places and causes of death.

Beginning in 1989, the newspaper Pravda published what it claimed was reliable data on losses of nearly 14,000 Soviet troops. By the end of the 20th century, this number reached 15,000, since the wounded Soviet soldier of the Afghan War was already dying at home due to injuries or illnesses. These were the true consequences of the Soviet-Afghan War.

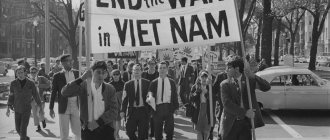

Some mentions of combat losses from the Soviet leadership further intensified conflict situations with the public. And at the end of the 80s, demands for the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan were almost the main slogan of that era. During the stagnant years, this was demanded by the dissident movement. In particular, academician Andrei Sakharov was exiled to Gorky for criticizing the “Afghan issue”.

Consequences of the Afghan War: results

What were the consequences of the Afghan conflict? The Soviet invasion extended the existence of the ruling party exactly as long as a limited contingent of troops remained in the country. With their withdrawal, the ruling regime came to an end. Numerous Mujahideen detachments quickly managed to regain control over the territory of all of Afghanistan. Some Islamist groups began to appear near the Soviet borders, and border guards were often under fire from them even after the end of hostilities.

Since April 1992, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan no longer existed; it was completely liquidated by Islamists. The country was in complete chaos. It was divided by numerous factions. The war against everyone there lasted until the invasion of NATO troops after the New York terrorist attacks in 2001. In the 90s, the Taliban movement emerged in the country, which managed to achieve a leading role in modern world terrorism.

In the minds of post-Soviet people, the Afghan war has become one of the symbols of the passing Soviet era. Songs, films, and books were dedicated to the theme of this war. Nowadays, in schools it is mentioned in history textbooks for high school students. It is assessed differently, although almost everyone in the USSR was against it. The echo of the Afghan war still haunts many of its participants.

345th Regiment

A separate unit that was transferred to Bagram was the 345th regiment. He reinforced the battalion of the 111th Regiment. The ninth company of this formation took part in the attack on Amin's palace. In 1998 it was disbanded.

The participation of the Union Army in the internal conflict of the Republic of Afghanistan became the longest and most extensive, which was carried out outside the territory of the state in peacetime. More than 600 military personnel served in Afghanistan, for which many received awards and medals.