Advocates of Maritime Trade

Kent class cruisers confirmed the British penchant for building highly specialized combat units without thinking about what would happen if the ship encountered the wrong enemy for which it was built to fight.

However, they completed their main task without even engaging in battle.

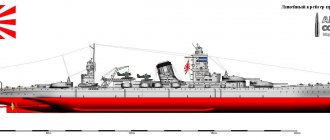

The possible appearance of armored cruisers in the French and Russian navies, intended for raids on the sea lanes of the British Empire, in the 1890s was an unpleasant surprise for the British Admiralty: the squadron battleships had too low speed, and the armored cruisers were too lightly armed to counter the new ships potential opponents. Initially, the British tried to adapt already existing types of ships for this, creating 2nd class battleships of the Centurion type (also known as “colonial” battleships) and large armored cruisers of the Powerfull type, however, quickly becoming convinced of their low efficiency, they decided to start building armored cruisers -trade protection cruisers.

The first British armored cruisers were ships of the Cressy class, which were essentially a version of the Powerfull armored cruiser equipped with an armor belt. According to one version, the Cressy class received its name in honor of the medieval victory of the English army over the French at Cresy (1346), since it was intended primarily to fight the French cruisers of the Guyedon class. The Cressy class cruisers were heavily influenced by the Italian armored cruisers Carlo Alberto and Giuseppe Garibaldi, conceptually intended not only for trade protection, but also for joint operations with battle squadrons as fast vanguard ships. Such a half-hearted approach could not have positive results, and as a result, having received enhanced armor, the Cressy-class cruisers began to be inferior to the potential enemy in speed (21 knots versus 22 knots for the French Guyedon-class cruisers or Russian Bayan-class cruisers).

Kent and Drake are trade advocates

To counter the new French and Russian armored cruisers, the British also created two types of highly specialized trade defender cruisers, not intended to participate in the operations of the armored fleet. On Drake-class cruisers, the increase in speed was achieved by increasing the power of the energy system, which entailed an increase in displacement, and on Kent-class cruisers (this type is also called Monmouth) - by weakening the armor and armament. Today there is no clear answer to the question of what exactly forced the British to create two types of ships at once. According to one version, the Kent-class cruisers were a “budget” version of the Drake-class cruisers, designed to bring the number of ships under construction to the required minimum. We must admit that this version has a right to life, since the defending side needs more ships than the attacking side. At least a third of warships are usually under repair, and the remaining two-thirds can be used almost simultaneously by the naval command planning an attack. Unlike the attacker, the defending side is forced to constantly patrol dangerous areas (a third of its ships are in the patrol zone; a third are under repair, a third are moving to the patrol zones and back). Thus, in the last years of the 19th century, the British needed approximately twenty-four cruisers to counter four Russian and eight French cruisers.

According to another version, Drake-class cruisers were supposed to be used in the Atlantic Ocean against more powerful ships of the French Navy, and Kent - in the Pacific Ocean against worse-armed Russian cruisers. This version is supported by the simultaneous construction of both series, and against it by the creation of more ships to fight the Russian fleet, which had fewer combat units. What exactly was the root cause of the appearance of Kent-class cruisers is apparently not so important. Much more important is the fact that it was these often criticized ships that raised doubts in France and Russia about the victoriousness of the cruising war.

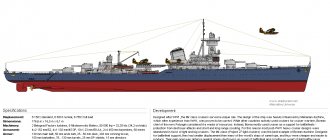

Schematic of the Kent (Monmouth) class cruiser Source: steelnavy.com

Performance characteristics

Kent-class cruisers were created as compact ships with moderate displacement and armament (a special requirement was the ability for them to pass the Suez Canal with a full coal load).

The ships had a rather low three-tube silhouette and, in general, had good seaworthiness, but the narrowed contours in the bow and stern, combined with the heavy stern and bow artillery towers, caused strong pitching at high waves. A total of ten units were built, making Kent the most massive series of armored cruisers in the history of world shipbuilding. Kent-class armored cruisers

| Ship | Shipyard | Bookmark date | Launch date | Commissioning date |

| Monmouth | London and Glasgow Co., Glasgow | 29.08.1899 | 13.11.1901 | 02.12.1903 |

| Essex | Navy Dockyard, Penbroke | 01.01.1900 | 29.08.1901 | 22.03.1904 |

| Kent | Naval Dockyard, Portsmouth | 12.02.1900 | 06.03.1901 | 1.10.1903 |

| Bedford | Fairfield, Govan | 19.02.1900 | 31.08.1901 | 11.11.1903 |

| Donegal | Fairfield, Govan | 14.02.1901 | 04.09.1902 | 05.11.1903 |

| Cumberland | London and Glasgow Co., Glasgow | 19.02.1901 | 16.12.1902 | 01.12.1904 |

| Lancaster | Armstrong, Elswick | 04.03.1901 | 22.03.1902 | 05.04.1904 |

| Cornwall | Navy Dockyard, Penbroke | 11.03.1901 | 29.10.1902 | 01.12.1904 |

| Suffolk | Naval Dockyard, Portsmouth | 25.03.1901 | 15.01.1903 | 21.05.1904 |

| Berwick | Beardmore, Dalmoor | 19.04.1901 | 20.09.1902 | 09.12.1903 |

The cruisers Kent and Essex were ordered as part of amendments to the shipbuilding program of 1898/99, Monmouth and Bedford - to the program of 1899/1900, and others - a year later. There is a version that they deliberately delayed the construction of the cruisers Kent and Essex, insisting on making changes to the project, but it seems more likely that changes to the program were made already in 1899. The Kent-class cruisers were criticized already at the construction stage, with many British naval experts pointing out that they were "not suited to effectively perform the tasks for which the ships were designed."

.

Cruiser Kent Source: iwm.org.uk

Basic geometric dimensions of Kent-class cruisers

| Total displacement, t | 9956 |

| Length, m | 141,27 |

| Width, m | 20,12 |

| Draft, m | 7,62 |

The number of cruiser crews ranged from 678 to 735 people.

Power plant

Each cruiser received a two-shaft power plant, consisting of two triple expansion steam engines and thirty-one Belleville boilers (Cornwall - Babcock boilers; Suffolk and Berwick - Nicloss boilers). The total power of the power plant was 22,189 liters. With. A design feature first used in the British Navy was the exhaust of the chimneys into three pipes of increased diameter (previous battleships had four pipes). The actual speed of the cruisers was slightly different from that established by the contract (23 knots). The fastest were Suffolk and Lancaster (24.7 and 24 knots, respectively), the slowest were Monmouth, Essex and Kent (according to various sources, 22.4–22.8 knots). The speed of the remaining cruisers was 23.6–23.7 knots. During the Battle of Falklands, the cruiser Kent managed to reach a speed of 25 knots, for which “furniture and teak wood torn from the deck had to be burned in the fireboxes.”

, however, it seems more likely that the increase in speed was provided not by exotic fuel, but by steam production and the use of steam. According to historian Fyodor Lisitsyn, multiple expansion steam engines of those years were designed for a steam expansion ratio of 8.5-10.5, which made it possible to achieve the maximum power of the machine for a given boiler steam output. Most likely, the mechanics of the cruiser Kent could have lowered this parameter to 6.5-7 for a short time, that is, actually completely cut off the operation of the low-pressure cylinders, dumping steam into the refrigerators, but increasing the power of the machine.

Cruiser Kent Source: iwm.org.uk

Power plants of Kent-class cruisers and their potential opponents

| Kent | Guyedon | «Accordion» | |

| A country | Great Britain | France | Russia |

| Year of laying of the lead ship | 1899 | 1898 | 1899 |

| Displacement, t | 9956 | 9367 | 7725 |

| Power, installations, hp | 22 189 | 19 600 | 16 500–17 400 |

| Specific power of the unit hp/t | 2,23 | 2,09 | 2,25 |

| Fuel type | Coal | Coal | Coal |

| Fuel reserve, t | 1600 | 1575 | 1100 |

| Maximum speed, knots | 22,4–24,7 | 21–22 | 20,9–22,5 |

| Economical speed, knots | 10 | No data | 10 |

| Cruising range, miles | 6600 | No data | 3900 |

| Specific fuel consumption, t/mile | 0,24 | No data | 0,28 |

The power plant was actually the only system of the cruiser that did not cause significant complaints. With excellent efficiency, it provided an even higher maximum speed than that of potential opponents (the latter's speed ended up being lower than the initially announced 23 knots).

Notes

- All characteristics are given according to Nenakhov Yu. Yu. Decree. Op. P. 308.

- ↑ 12345

Victorian Era, 2012, p. 672. - ↑ 12

Kreisera, 2015, p. 50. - Victorian Era, 2012, p. 875.

- Jane's Fighting Ships 1919 p 72

- A. Sick cruisers in battle.

- ↑ 123

Kreisera, 2015, p. 52. - ↑ 12

Kreisera, 2015, p. 51. - Zablotsky V.P.

All the heroic army. Armored cruisers of the "Bogatyr" class. Part 1 // Marine collection. - 2010. - No. 3. - P. 6-7. - Malkov D. G., Tsarkov A. Yu.

Ships of the Russian-Japanese War. Russian Imperial Navy // Marine collection. - 2009. - No. 7. - P. 12. - Nenakhov Yu. Yu.

Encyclopedia of cruisers 1860-1910. — P. 328. - Nenakhov Yu. Yu.

Encyclopedia of cruisers 1860-1910. — P. 191. - Nenakhov Yu. Yu.

Encyclopedia of cruisers 1860-1910. — P. 208. - Kreisera, 2015, p. 53.

- All the World's Fighting Ships 1860—1905 / R. Gardiner. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1979. - P. 305.

- All the World's Fighting Ships 1860—1905 / R. Gardiner. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1979. - P. 149.

- All the World's Fighting Ships 1860—1905 / R. Gardiner. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1979. - P. 70.

- Gröner

. Band 1. - P.78 - All the World's Fighting Ships 1860—1905 / R. Gardiner. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1979. - P. 225.

- All the World's Fighting Ships 1860—1905 / R. Gardiner. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1979. - P. 306.

Comments

- The series is also called the "Monmouth"

- Test speed, continuous speed, rough speed.

- It was estimated to be 3½ inches thick nickel (88 mm, actually 100 mm Garvevskaya), which should be inferior in durability to uncemented Kruppovskaya (in fact it was the other way around)

- For British and American ships, the sources give displacement in long tons, so it is converted to metric tons

Construction program[edit]

The following table shows the assembly details and purchase costs of members of the Monmouth

.

Standard British practice at the time was that these costs did not include

weapons and supplies. The compilers of The Naval Annual revised the values of British ships between the 1905 and 1906 editions. The reasons for the differences are unclear. [2]

| Ship | Builder | Engine Maker | date | Cost according to | |||

| Stacked | Launch | Completion | (BNA 1905) [3] | (BNA 1906) [4] | |||

| Monmouth | Transport for London and Glasgow | Transport for London and Glasgow | August 29, 1899 | November 13, 1901 | December 2, 1903 | £709,085 | £ 979 591 |

| Bedford | Fairfield, Govan | Fairfield | February 19, 1900 | August 31, 1901 | November 11, 1903 | £734,330 | £706,020 |

| Essex | Pembroke Shipyard | J. Brown | January 1, 1900 | August 29, 1901 | March 22, 1903 | £770,325 | £736,557 |

| Kent | Portsmouth Dockyard | Hawthorn | February 12, 1900 | March 6, 1901 | October 1, 1903 | £733,940 | £700,283 |

| Berwick | W. Beardmore & Company | Humphreys | April 19, 1901 | September 20, 1902 | December 9, 1903 | £776,868 | £750,984 |

| Cornwall | Pembroke Shipyard | Hawthorn | March 11, 1901 | October 29, 1902 | December 1, 1904 | £789,421 | £756,274 |

| Cumberland | London and Glasgow Transport Company, Glasgow | Transport for London and Glasgow | February 19, 1901 | December 16, 1902 | December 1, 1904 | £751,508 | £718,168 |

| Donegal | Fairfield, Govan | Fairfield | February 14, 1901 | September 4, 1902 | 5 Nov. 1903 | £752,964 | £715,947 |

| Lancaster | Armstrong, Elswick | Hawthorn | March 4, 1901 | March 22, 1903 | April 5, 1904 | £763,084 | £732,858 |

| Suffolk | Portsmouth Dockyard | Humphreys | March 25, 1901 | January 15, 1903 | May 21, 1904 | £783,054 | £722,681 |

Literature

- Nenakhov Yu. Yu.

Encyclopedia of cruisers 1860-1910. - Minsk: Harvest, 2006. - ISBN 5-17-030194-4. - Lisitsyn F.V.

Cruisers of the First World War. - M.: Yauza, EKSMO, 2015. - ISBN 978-5-699-84344-2. - Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860-1905. - London: Conway Maritime Press, 1980. - ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Norman Friedman.

British Cruisers of the Victorian Era. - Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth, 2012. - ISBN 978-1-59114-068-9. - Gröner, Erich.

Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1815-1945 Band 1: Panzerschiffe, Linienschiffe, Schlachschiffe, Flugzeugträger, Kreuzer, Kanonenboote. - Bernard & Graefe Verlag, 1982. - 180 p. — ISBN 978-3763748006.

| Nelson type | "Nelson" · "Northampton" |

| Imperuse type | "Imperuse" · "Warspite" |

| Orlando type | "Orlando" · "Australia" · "Undowned" · "Narcissus" · "Galatea" · "Immortelite" · "Aurora" |

| Cressy type | "Cressi" · "Sutli" · "Aboukir" · "Hog" · "Bashanti" · "Yuriales" |

| Drake type | "Drake" · "Good Hope" · "Leviathan" · "King Alfred" |

| type "Kent" | Kent Essex Bedford Monmouth Lancaster Donegal Berwick Cornwall Cumberland Suffolk |

| Devonshire type | Devonshire · Hampshire · Carnarvon · Antrim · Roxborough · Argyle |

| Duke of Edinburgh type | Duke of Edinburgh · Black Prince |

| Warrior type | Warrior · Cochrane · Achilles · Natal |

| "Minotaur" type | "Minotaur" · "Shannon" · "Defence" |

| Turret, barbette and casemate battleships | Devastation class Dreadnought Neptune Inflexible Ajax class Colossus class Admiral class Trafalgar class Alexandra Superb Temeraire class "Beleil" |

| Armored rams | type "Conqueror" type "Victoria" |

| Coastal defense battleships | "Glatton" · type "Cyclops" |

| Armored cruisers | Nelson type · Imperious type · Orlando type · Cressy type · Drake type · Kent type · Devonshire type · Duke of Edinburgh type · Warrior type |

| Armored cruisers | Blake type · Edgar type · Powerful type · Diadem type · Comus type · Calypso type · Linder type · River type · Medea type · Apollo type · Astraea class · Eclipse class · Errogant class · Highflyer class · Challenger class · Barracouta class · Barham class · Pearl class · Pelorus class · Jem class |

| Cruiser Scouts | Sentinel type · Adventure type · Forward type · Pathfinder type |

| Destroyers | 26-knot type · 27-knot type · 30-knot type · Special 33-knot type · River type · Tribal type · Taku |

| Destroyers | 160ft type 140ft type Indian type 130ft type 125ft type |

| Submarines | type "A" · type "B" · type "C" |

Service [edit]

Upon completion, the ships served for some time in home waters and were then assigned to various overseas stations (China, Halifax and the Caribbean). During this time HMS Bedford

Wrecked in the East China Sea and scrapped.

After the outbreak of World War I, the ships were primarily tasked with fighting German merchant raiders, patrolling both the North and South Atlantic. HMS Monmouth

was assigned to Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock's squadron and was sunk at the Battle of Coronel.

HMS Kent

was also assigned to Cradock's squadron, but was unable to join in time;

she remained in the Falklands and joined Admiral Sturdee's squadron, which also included HMS Cornwall

.

In the ensuing Battle of the Falkland Islands, HMS Kent

pursued and sank Nuremberg, while HMS

Cornwall

pursued and sank Leipzig.

HMS Kent

continued her pursuit of Dresden, eventually discovering her and causing her to be scuttled at the Battle of Mas a Tierra.

HMS Cornwall

took part in the blockade of Königsberg on the Rufiji River.

After the war, several ships served for some time as training ships. All were withdrawn from service and scrapped in 1920–21.

An excerpt characterizing the Kent-class armored cruisers

- So that no one knows anything! – the sovereign added, frowning. Boris realized that this applied to him, and, closing his eyes, bowed his head slightly. The Emperor again entered the hall and remained at the ball for about half an hour. Boris was the first to learn the news about the crossing of the Neman by French troops and thanks to this he had the opportunity to show some important persons that he knew many things hidden from others, and through this he had the opportunity to rise higher in the opinion of these persons. The unexpected news about the French crossing the Neman was especially unexpected after a month of unfulfilled anticipation, and at a ball! The Emperor, at the first minute of receiving the news, under the influence of indignation and insult, found what later became famous, a saying that he himself liked and fully expressed his feelings. Returning home from the ball, the sovereign at two o'clock in the morning sent for secretary Shishkov and ordered to write an order to the troops and a rescript to Field Marshal Prince Saltykov, in which he certainly demanded that the words be placed that he would not make peace until at least one the armed Frenchman will remain on Russian soil. The next day the following letter was written to Napoleon. “Monsieur mon frere. J'ai appris hier que malgre la loyaute avec laquelle j'ai maintenu mes engagements envers Votre Majeste, ses troupes ont franchis les frontieres de la Russie, et je recois a l'instant de Petersbourg une note par laquelle le comte Lauriston, pour cause de cette aggression, annonce que Votre Majeste s'est consideree comme en etat de guerre avec moi des le moment ou le prince Kourakine a fait la demande de ses passeports. Les motifs sur lesquels le duc de Bassano fondait son refus de les lui delivrer, n'auraient jamais pu me faire supposer que cette demarche servirait jamais de pretexte a l'agression. En effet cet ambassadeur n'y a jamais ete autorise comme il l'a declare lui meme, et aussitot que j'en fus informe, je lui ai fait connaitre combien je le desapprouvais en lui donnant l'ordre de rester a son poste. Si Votre Majeste n'est pas intentionnee de verser le sang de nos peuples pour un malentendu de ce genre et qu'elle consente a retirer ses troupes du territoire russe, je regarderai ce qui s'est passe comme non avenu, et un accommodement entre nous sera possible. Dans le cas contraire, Votre Majeste, je me verrai force de repousser une attaque que rien n'a provoquee de ma part. Il depend encore de Votre Majeste d'eviter a l'humanite les calamites d'une nouvelle guerre. Je suis, etc. (signe) Alexandre.” [“My lord brother! Yesterday it dawned on me that, despite the straightforwardness with which I observed my obligations towards Your Imperial Majesty, your troops crossed the Russian borders, and only now have I received a note from St. Petersburg, with which Count Lauriston informs me regarding this invasion, that Your Majesty considers yourself to be on hostile terms with me from the time Prince Kurakin demanded his passports. The reasons on which the Duke of Bassano based his refusal to issue these passports could never have led me to suppose that the act of my ambassador served as a reason for the attack. And in fact, he did not have a command from me to do this, as he himself announced; and as soon as I learned about this, I immediately expressed my displeasure to Prince Kurakin, ordering him to carry out the duties entrusted to him as before. If Your Majesty is not inclined to shed the blood of our subjects because of such a misunderstanding and if you agree to withdraw your troops from Russian possessions, then I will ignore everything that happened, and an agreement between us will be possible. Otherwise, I will be forced to repel an attack that was not provoked by anything on my part. Your Majesty, you still have the opportunity to save humanity from the scourge of a new war. (signed) Alexander.” ] On June 13, at two o'clock in the morning, the sovereign, calling Balashev to him and reading him his letter to Napoleon, ordered him to take this letter and personally hand it over to the French emperor. Sending Balashev away, the sovereign again repeated to him the words that he would not make peace until at least one armed enemy remained on Russian soil, and ordered that these words be conveyed to Napoleon without fail. The Emperor did not write these words in the letter, because he felt with his tact that these words were inconvenient to convey at the moment when the last attempt at reconciliation was being made; but he certainly ordered Balashev to hand them over to Napoleon personally. Having left on the night of June 13th to 14th, Balashev, accompanied by a trumpeter and two Cossacks, arrived at dawn in the village of Rykonty, at the French outposts on this side of the Neman. He was stopped by French cavalry sentries. A French hussar non-commissioned officer, in a crimson uniform and a shaggy hat, shouted at Balashev as he approached, ordering him to stop. Balashev did not stop immediately, but continued to walk along the road. The non-commissioned officer, frowning and muttering some kind of curse, advanced with the chest of his horse towards Balashev, took up his saber and rudely shouted at the Russian general, asking him: is he deaf, that he does not hear what is being said to him. Balashev identified himself. The non-commissioned officer sent the soldier to the officer. Not paying attention to Balashev, the non-commissioned officer began to talk with his comrades about his regimental business and did not look at the Russian general. It was unusually strange for Balashev, after being close to the highest power and might, after a conversation three hours ago with the sovereign and generally accustomed to honors from his service, to see here, on Russian soil, this hostile and, most importantly, disrespectful attitude towards himself with brute force. The sun was just beginning to rise from behind the clouds; the air was fresh and dewy. On the way, the herd was driven out of the village. In the fields, one by one, like bubbles in water, the larks burst into life with a hooting sound. Balashev looked around him, waiting for the arrival of an officer from the village. The Russian Cossacks, the trumpeter, and the French hussars silently looked at each other from time to time. A French hussar colonel, apparently just out of bed, rode out of the village on a beautiful, well-fed gray horse, accompanied by two hussars. The officer, the soldiers and their horses wore an air of contentment and panache. This was the first time of the campaign, when the troops were still in good order, almost equal to the inspection, peaceful activity, only with a touch of smart belligerence in clothing and with a moral connotation of that fun and enterprise that always accompany the beginning of campaigns. The French colonel had difficulty holding back a yawn, but was polite and, apparently, understood the full significance of Balashev. He led him past his soldiers by the chain and said that his desire to be presented to the emperor would probably be fulfilled immediately, since the imperial apartment, as far as he knew, was not far away. They drove through the village of Rykonty, past French hussar hitching posts, sentries and soldiers saluting their colonel and curiously examining the Russian uniform, and drove out to the other side of the village. According to the colonel, the division chief was two kilometers away, who would receive Balashev and see him off to his destination. The sun had already risen and shone cheerfully on the bright greenery. They had just left the tavern on the mountain when a group of horsemen appeared from under the mountain to meet them, in front of which, on a black horse with harness shining in the sun, rode a tall man in a hat with feathers and black hair curled to the shoulders, in a red robe and with with long legs stuck out forward, like the French ride. This man galloped towards Balashev, his feathers, stones and gold braid shining and fluttering in the bright June sun. Balashev was already two horses away from the horseman galloping towards him with a solemnly theatrical face in bracelets, feathers, necklaces and gold, when Yulner, the French colonel, respectfully whispered: “Le roi de Naples.” [King of Naples.] Indeed, it was Murat, now called the King of Naples. Although it was completely incomprehensible why he was the Neapolitan king, he was called that, and he himself was convinced of this and therefore had a more solemn and important appearance than before. He was so sure that he was really the Neapolitan king that, on the eve of his departure from Naples, while he was walking with his wife through the streets of Naples, several Italians shouted to him: “Viva il re!” [Long live the king! (Italian) ] he turned to his wife with a sad smile and said: “Les malheureux, ils ne savent pas que je les quitte demain! [Unfortunate people, they do not know that I am leaving them tomorrow!] But despite the fact that he firmly believed that he was the Neapolitan king, and that he regretted the sorrow of his subjects leaving him, recently, after he was ordered to enter the service again, and especially after a meeting with Napoleon in Danzig, when the august brother-in-law told him: “Je vous ai fait Roi pour regner a maniere, mais pas a la votre,” [I made you king in order to to reign not in his own way, but in mine.] - he cheerfully set about a task familiar to him and, like a well-fed, but not fat, horse fit for service, sensing himself in the harness, began to play in the shafts and, having discharged himself as colorfully and expensively as possible, cheerful and happy, he galloped, without knowing where or why, along the roads of Poland. Seeing the Russian general, he royally and solemnly threw back his head with shoulder-length curled hair and looked questioningly at the French colonel. The Colonel respectfully conveyed to His Majesty the significance of Balashev, whose surname he could not pronounce. - De Bal macheve! - said the king (with his decisiveness overcoming the difficulty presented to the colonel), - charme de faire votre connaissance, general, [it’s very nice to meet you, general] - he added with a royally gracious gesture. As soon as the king began to speak loudly and quickly, all royal dignity instantly left him, and he, without noticing it, switched to his characteristic tone of good-natured familiarity. He put his hand on the withers of Balashev's horse. “Eh, bien, general, tout est a la guerre, a ce qu'il parait, [Well, general, things seem to be heading towards war," he said, as if regretting a circumstance about which he did not could judge. “Sire,” answered Balashev. “l'Empereur mon maitre ne desire point la guerre, et comme Votre Majeste le voit,” said Balashev, using Votre Majeste in all cases, [The Russian Emperor does not desire her, as your Majesty is pleased to see... your Majesty.] with inevitable the affectation of increasing the frequency of the title, addressing a person for whom this title is still news. Murat's face shone with stupid contentment as he listened to Monsieur de Balachoff. But royaute oblige: [the royal rank has its responsibilities:] he felt the need to talk with Alexander's envoy about state affairs, as a king and an ally. He got off his horse and, taking Balashev by the arm and moving a few steps away from the respectfully waiting retinue, began walking with him back and forth, trying to speak significantly. He mentioned that Emperor Napoleon was offended by the demands for the withdrawal of troops from Prussia, especially now that this demand had become known to everyone and when the dignity of France was insulted. Balashev said that there was nothing offensive in this demand, because... Murat interrupted him: “So you don’t think Emperor Alexander was the instigator?” - he said unexpectedly with a good-naturedly stupid smile. Balashev said why he really believed that Napoleon was the start of the war. “Eh, mon cher general,” Murat interrupted him again, “je desire de tout mon c?ur que les Empereurs s'arrangent entre eux, et que la guerre commencee malgre moi se termine le plutot possible, [Ah, dear general, I wish with all my heart that the emperors put an end to the matter between themselves and that the war, started against my will, ends as soon as possible.] - he said in the tone of the conversation of servants who want to remain good friends, despite the quarrel between the masters. And he moved on to questions about the Grand Duke, about his health and about the memories of the fun and amusing time spent with him in Naples. Then, as if suddenly remembering his royal dignity, Murat solemnly straightened up, took the same position in which he stood at the coronation, and, waving his right hand, said: “Je ne vous retiens plus, general; je souhaite le succes de vorte mission, [I will not detain you any longer, General; I wish your embassy success,] - and, fluttering with a red embroidered robe and feathers and glittering with jewelry, he went to the retinue, respectfully waiting for him. Balashev went further, according to Murat, expecting to be introduced to Napoleon himself very soon. But instead of a quick meeting with Napoleon, the sentries of Davout's infantry corps again detained him at the next village, as in the advanced chain, and the adjutant of the corps commander was summoned and escorted him to the village to see Marshal Davout. Davout was Arakcheev of the Emperor Napoleon - Arakcheev is not a coward, but just as serviceable, cruel and unable to express his devotion except by cruelty. The mechanism of the state organism needs these people, just as wolves are needed in the body of nature, and they always exist, always appear and stick around, no matter how incongruous their presence and proximity to the head of government seems. Only this necessity can explain how the cruel, uneducated, uncourtly Arakcheev, who personally tore out the mustaches of the grenadiers and could not withstand danger due to his weak nerves, could maintain such strength despite the knightly noble and gentle character of Alexander. Balashev found Marshal Davout in the barn of a peasant's hut, sitting on a barrel and busy with writing (he was checking accounts). The adjutant stood next to him. It was possible to find a better place, but Marshal Davout was one of those people who deliberately put themselves in the gloomiest conditions of life in order to have the right to be gloomy. For the same reason, they are always hastily and persistently busy. “Where is there to think about the happy side of human life, when, you see, I’m sitting on a barrel in a dirty barn and working,” said the expression on his face. The main pleasure and need of these people is to, having encountered the revival of life, throw gloomy, stubborn activity into the eyes of this revival. Davout gave himself this pleasure when Balashev was brought in to him. He went even deeper into his work when the Russian general entered, and, looking through his glasses at Balashev’s animated face, impressed by the wonderful morning and the conversation with Murat, he did not get up, did not even move, but frowned even more and grinned viciously. Noticing the unpleasant impression this technique produced on Balashev’s face, Davout raised his head and coldly asked what he needed. Assuming that such a reception could be given to him only because Davout does not know that he is the adjutant general of Emperor Alexander and even his representative before Napoleon, Balashev hastened to announce his rank and appointment. Contrary to his expectations, Davout, after listening to Balashev, became even more severe and rude. - Where is your package? - he said. – Donnez le moi, ije l'enverrai a l'Empereur. [Give it to me, I will send it to the emperor.] Balashev said that he had orders to personally deliver the package to the emperor himself. “The orders of your emperor are carried out in your army, but here,” said Davout, “you must do what you are told.” And as if in order to make the Russian general even more aware of his dependence on brute force, Davout sent the adjutant for the duty officer. Balashev took out the package containing the sovereign’s letter and placed it on the table (a table consisting of a door with torn hinges sticking out, placed on two barrels). Davout took the envelope and read the inscription. “You have absolutely the right to show or not show me respect,” said Balashev. “But let me note that I have the honor to bear the rank of His Majesty’s Adjutant General...” Davout looked at him silently, and some excitement and embarrassment expressed on Balashev’s face apparently gave him pleasure. “You will be given your due,” he said and, putting the envelope in his pocket, he left the barn. A minute later, the Marshal's adjutant, Mr. de Castres, entered and led Balashev into the room prepared for him. Balashev dined that day with the marshal in the same barn, on the same board on barrels. The next day, Davout left early in the morning and, inviting Balashev to his place, impressively told him that he asked him to stay here, move along with his luggage if they had orders to do so, and not talk to anyone except Mister de Castro.

Links[edit]

- ^ B s d e g h i JK Lenton

- Marriot (2005) p. 3, paragraph 23

- Cuthbert Headlam (20 February 1922). "Cruiser Construction (Cost)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

.

Milbanksystems

.

225

. Milbanksystems. col. 1104. Retrieved May 24 +2016. - ^ a b c d Marriot (2005)

- NavWeaps.com, British 8"/50 (20.3 cm) Mark VIII

- Campbell (2002)

- Marriot (2005) P.3, para. 6

- Marriot (2005) P.3, para. 9

- Marriot (2005) p. 2, paragraph 14

- Marriot (2005) Appendix 3, paragraph 4