Cruiser "Varyag". Battle of Chemulpo January 27, 1904

Cruiser "Varyag". During the Soviet era, there would hardly have been a person in our country who had never heard of this ship. For many generations of our compatriots, the Varyag became a symbol of the heroism and dedication of Russian sailors in battle.

However, perestroika, glasnost and the “wild 90s” that followed came. Our history has been revised by all and sundry, and throwing mud at it has become a fashionable trend. Of course, “Varyag” also got it, and in full. His crew and commander were accused of everything! It was already agreed that Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev deliberately (!) sank the cruiser where it could be easily raised, for which he subsequently received a Japanese order. But on the other hand, many sources of information have appeared that were not previously available to historians and lovers of naval history - perhaps their study can really make adjustments to the history of the heroic cruiser, familiar to us from childhood?

This series of articles, of course, will not dot all the i's. But we will try to bring together information about the history of the design, construction and service of the cruiser up to and including Chemulpo, based on the data available to us, we will analyze the technical condition of the ship and the training of its crew, possible breakthrough options and various scenarios of action in battle. We will try to figure out why the commander of the cruiser, Vsevolod Fedorovich Rudnev, made certain decisions. In light of the above, we will analyze the postulates of the official version of the Varyag battle, as well as the arguments of its opponents. Of course, the author of this series of articles has formed a certain view of the feat of the “Varyag”, and it will, of course, be presented. But the author sees his task not in persuading the reader to any point of view, but in giving maximum information, on the basis of which everyone can decide for himself what the actions of the commander and crew of the cruiser "Varyag" are for him - a reason be proud of the fleet and your country, a shameful page in our history, or something else.

Well, we’ll start with a description of where such an unusual type of warship came from in Russia, such as high-speed armored cruisers of the 1st rank with a normal displacement of 6-7 thousand tons.

The ancestors of the armored cruisers of the Russian Imperial Navy can be considered the armored corvettes “Vityaz” and “Rynda” with a normal displacement of 3,508 tons, built in 1886.

Three years later, the Russian fleet was replenished with a larger armored cruiser with a displacement of 5,880 tons - it was the Admiral Kornilov, ordered in France, the construction of which began at the Loire shipyard (Saint-Nazaire) in 1886. However, then there was a slowdown in the construction of armored cruisers in Russia a long pause - almost a decade, from 1886 to 1895, the Russian Imperial Navy did not order a single ship of this class. Yes, and the Svetlana (with a displacement of 3828 tons), laid down at the end of 1895 at the French shipyards, although it was a quite decent small armored cruiser for its time, was still built rather as a representative yacht for the admiral general, and not as a ship , corresponding to the doctrine of the fleet. “Svetlana” did not fully meet the requirements for this class of warships by Russian sailors, and therefore was built in a single copy and was not replicated at domestic shipyards.

What, strictly speaking, were the fleet’s requirements for armored cruisers?

The fact is that the Russian Empire in the period 1890-1895. began seriously strengthening its Baltic Fleet with squadron battleships. Before this, in 1883 and 1886. two “battleships-rams” “Emperor Alexander II” and “Emperor Nicholas I” were laid down, and then only in 1889 - “Navarin”. Very slowly - one armadillo every three years. But in 1891 the Sisoy the Great was laid down, in 1892 - three squadron battleships of the Sevastopol type, and in 1895 - Peresvet and Oslyabya. And this is not counting the laying of three coastal defense battleships of the Admiral Senyavin class, from which, in addition to solving traditional tasks for this class of ships, they were also expected to support the main forces in the general battle with the German fleet.

In other words, the Russian fleet sought to create armored squadrons for a general battle, and of course, such squadrons required ships to support their operations. In other words, the Russian Imperial Navy needed reconnaissance officers attached to the squadrons - it was precisely this role that armored cruisers could quite successfully perform.

However, here, alas, dualism had its say, which largely predetermined the development of our fleet at the end of the 19th century. When creating the Baltic Fleet, Russia wanted to get a classic “two in one”. On the one hand, forces were required that were capable of giving a general battle to the German fleet and establishing dominance in the Baltic. On the other hand, they needed a fleet capable of entering the ocean and threatening British communications. These tasks were completely contradictory to each other, since their solution required different types of ships: for example, the armored cruiser Rurik was excellent for ocean raiding, but was completely inappropriate in a linear battle. Strictly speaking, Russia needed a battle fleet to dominate the Baltic and, separately, a second cruising fleet for war in the ocean, but, of course, the Russian Empire could not build two fleets, if only for economic reasons. Hence the desire to create ships capable of equally effectively fighting enemy squadrons and cruising in the ocean: a similar trend affected even the main strength of the fleet (the Peresvet series of “battleship cruisers”), so it would be strange to think that armored cruisers would not be supplied similar task.

As a matter of fact, this is exactly how the requirements for the domestic armored cruiser were determined. He was supposed to become a scout for the squadron, but also a ship suitable for ocean cruising.

Russian admirals and shipbuilders at that time did not at all consider themselves “ahead of the rest,” so when creating a new type of ship they paid close attention to ships of a similar purpose, built by the “Mistress of the Seas” - England. What happened in England? In 1888-1895. Foggy Albion built a large number of 1st and 2nd class armored cruisers.

At the same time, 1st class ships, strange as it may sound, were the “successors” of the Orlando-class armored cruisers. The fact is that these armored cruisers, according to the British, did not live up to the hopes placed on them; due to overload, their armor belt went under the water, thereby not protecting the waterline from damage, and in addition, in England, William took the post of chief builder White, opponent of armored cruisers. Therefore, instead of improving this class of ships, England in 1888 began building large armored cruisers of the 1st rank, the first of which were the Blake and Blenheim - huge ships with a displacement of 9150-9260 tons, carrying a very powerful armored deck (76 mm, and on bevels - 152 mm), strong weapons (2 * 234 mm, 10 * 152 mm, 16 * 47 mm) and developing a very high speed for that time (up to 22 knots).

Armored cruiser "Blake"

However, these ships seemed to their lordships to be excessively expensive, so the next series of 8 cruisers of the Edgar type, which entered the stocks in 1889-1890, was smaller in displacement (7467-7820 tons), speed (18.5/20 knots at natural /forced traction) and armor (the thickness of the bevels decreased from 152 to 127 mm).

All these ships were formidable fighters, but they, in fact, were cruisers not for squadron service, but for the protection of ocean communications, that is, they were “defenders of trade” and “raider killers,” and as such, were not very suitable for the Russian fleet. In addition, their development led the British to a dead end - in an effort to create ships capable of intercepting and destroying armored cruisers of the Rurik and Rossiya type, the British in 1895 laid down the armored deck Powerful and Terrible, which had a total displacement of over 14 thousand. etc. The creation of ships of this size (and cost), without vertical armor protection, was obvious nonsense.

Therefore, the analogues for the newest Russian armored cruisers were considered to be the English 2nd class cruisers, which had similar functionality, that is, they could serve with squadrons and perform overseas service.

Since 1889-1890 Great Britain laid down as many as 22 Apollo-class armored cruisers, built in two subseries. The first 11 ships of this type had a displacement of about 3,400 tons and did not carry copper-wood plating of the underwater part, which slowed down the fouling of ships, while their speed was 18.5 knots with natural draft and 20 knots when boosting the boilers. The next 11 Apollo-class cruisers had copper-wood plating, which increased their displacement to 3,600 tons, and reduced their speed (natural thrust/boosted) to 18/19.75 knots respectively. The armor and armament of the cruisers of both subseries was the same - an armored deck with a thickness of 31.75-50.8 mm, 2 * 152 mm, 6 * 120 mm, 8 * 57 mm, 1 * 47 mm guns and four 356 mm torpedo tubes apparatus.

The next armored cruisers of the British, 8 ships of the Astraea type, laid down in 1891-1893, became a development of the Apollo, and, in the opinion of the British themselves, not a very successful development. Their displacement increased by almost 1,000 tons, reaching 4,360 tons, but the additional weight was spent on subtle improvements - the armor remained at the same level, the armament “increased” by only 2 * 120 mm guns, and the speed decreased further, amounting to 18 knots with natural thrust and 19.5 knots with forced thrust. However, they served as the prototype for the creation of a new series of British 2nd class armored cruisers.

In 1893-1895. The British are laying down 9 cruisers of the Eclipse type, which we called the “Talbot type” (the same “Talbot” that served as a stationary on the Chemulpo roadstead along with the cruiser “Varyag”). These were much larger ships, the normal displacement of which reached 5,600 tons. They were protected by a somewhat more solid armored deck (38-76 mm) and they carried more solid weapons - 5 * 152 mm, 6 * 120 mm, 8 * 76- mm and 6*47 mm guns, as well as 3*457 mm torpedo tubes. At the same time, the speed of the Eclipse-class cruisers was frankly modest - 18.5/19.5 knots with natural/forced thrust.

So, what conclusions did our admirals draw from observing the development of the armored cruiser class in the UK?

Initially, a competition was announced for the cruiser project, and exclusively among domestic designers. They were asked to present designs for a ship with a displacement of up to 8,000 tons and a speed of at least 19 knots. and artillery, which included 2*203 mm (at the extremities) and 8*120 mm guns. Such a cruiser for those years looked excessively large and strong for a reconnaissance officer attached to a squadron; one can only assume that the admirals, knowing the characteristics of the English 1st class armored cruisers, were thinking about a ship capable of resisting them in battle. But, despite the fact that during the 1894-1895 The competition resulted in very interesting projects (7,200 - 8,000 tons, 19 knots, 2-3*203 mm guns and up to 9*120 mm guns), they did not receive further development: it was decided to focus on British armored cruisers 2 -th rank.

At the same time, it was initially planned to focus on Astraea-class cruisers, with the obligatory achievement of 20 knot speeds and “a possibly larger area of operation.” However, almost immediately a different proposal arose: the engineers of the Baltic Shipyard presented MTK with preliminary studies of designs for cruisers with a displacement of 4,400, 4,700 and 5,600 tons. All of them had a speed of 20 knots and an armored deck 63.5 mm thick, only the armament differed - 2 * 152- mm and 8*120 mm on the first, 2*203 mm and 8*120 mm on the second and 2*203 mm, 4*152 mm, 6*120 mm on the third. A note accompanying the drafts explained:

“The Baltic Shipyard deviated from the English cruiser Astrea prescribed as an analogue, since it does not represent the most advantageous type among other new cruisers of different nations.”

Then the Eclipse-class cruisers were chosen as a “role model”, but then data became known about the French armored cruiser D'Entrecasteaux (7,995 tons, armament 2 * 240 mm in single-gun turrets and 12 * 138 mm , speed 19.2 knots). As a result, a new cruiser design was proposed with a displacement of 6,000 tons, a speed of 20 knots and armament of 2 * 203 mm and 8 * 152 mm. Alas, soon, by the will of the Admiral General, the ship lost its 203-mm guns for the sake of uniformity of calibers and... thus began the history of the creation of domestic armored cruisers of the Diana type.

It must be said that the design of this series of domestic cruisers has become an excellent illustration of where the road paved with good intentions leads. In theory, the Russian Imperial Navy was supposed to receive a series of excellent armored cruisers, superior to the British ones in many respects. The armored deck of a single 63.5 mm thickness provided at least equivalent protection to the English 38-76 mm. Ten 152-mm guns were preferable to the 5*152-mm, 6*120-mm English ship. At the same time, “Diana” was supposed to become significantly faster than “Eclipse” and this was the point.

Tests of warships of the Russian fleet did not include boosting the boilers; Russian ships had to show the contract speed using natural thrust. This is a very important point, which is usually missed by the compilers of ship personnel directories (and, alas, by the readers of these directories). So, for example, data is usually given that the Eclipse developed 19.5 knots, and this is true, but it is not indicated that this speed was achieved by boosting the boilers. At the same time, the contract speed of the Diana is only half a knot higher than that of the Eclipse, and in fact, cruisers of this type were only able to develop 19-19.2 knots. From this we can assume that the Russian cruisers turned out to be even less fast than their English “prototype”. But in fact, the “goddesses” developed their 19 knots of speed on natural thrust, at which the speed of the “Eclipses” was only 18.5 knots, that is, our cruisers, with all their shortcomings, were still faster.

However, let's return to the Diana project. As we said earlier, their protection was expected to be no worse, their artillery better, and their speed one and a half knots greater than that of the British Eclipse-class cruisers, but that was not all. The fact is that the Eclipses had fire-tube boilers, while the Dianas were planned to have water-tube boilers, and this gave our ships a number of advantages. The fact is that fire tube boilers require much more time for distributing vapors, it is much more difficult to change operating modes on them, and this is important for warships, and in addition, flooding a compartment with a working fire tube boiler would most likely lead to its explosion, which threatened the ship with immediate destruction (as opposed to the flooding of one compartment). Water tube boilers were free of these disadvantages.

The Russian fleet was one of the first to switch to water tube boilers. Based on the results of research by specialists from the Naval Department, it was decided to use boilers designed by Belleville, and the first tests of these boilers (the armored frigate Minin was converted in 1887) showed quite acceptable technical and operational characteristics. It was believed that these boilers were extremely reliable, and the fact that they were very heavy was perceived as an inevitable price to pay for other advantages. In other words, the Navy Department realized that there were boilers of other systems in the world, including those that could provide the same power at significantly less weight than the Belleville boilers, but all this had not been tested and therefore raised doubts. Accordingly, when creating armored cruisers of the Diana type, the requirement to install Belleville boilers was completely categorical.

However, heavy boilers are not at all the best choice for a high-speed (even relatively high-speed) armored cruiser. The weight of the “Dian” machines and mechanisms amounted to an absolutely absurd 24.06% of their normal displacement! Even the later-built Novik, which many spoke of as a “destroyer weighing 3,000 tons” and a “case for cars,” whose combat qualities were obviously sacrificed for speed - and its weight of cars and boilers was only only 21.65% of normal displacement!

The Diana-class armored cruisers in their final version had 6,731 tons of normal displacement, developed 19-19.2 knots and carried an armament of only eight 152 mm guns. Without a doubt, they turned out to be extremely unsuccessful ships. But it’s hard to blame the ship’s designers for this - the supermassive power plant simply did not leave them enough room to achieve the rest of the planned characteristics of the ship. Of course, the existing boilers and engines were not suitable for a high-speed cruiser, and even the admirals “distinguished themselves” by authorizing the weakening of the already weak weapons for the sake of saving a penny on the scales. And, what’s most offensive, all the sacrifices that were made for the power plant did not make the ship fast. Yes, despite not reaching the contract speed, they were, perhaps, still faster than the British Eclipses. But the problem was that the “Mistress of the Seas” did not often build really good ships (the British were just good at fighting with them), and the armored cruisers of this series certainly could not be called successful. Strictly speaking, neither the 18.5 Eclipse nodes nor the 20 contract Diana nodes in the second half of the 90s of the 19th century were sufficient to serve as a reconnaissance unit for the squadron. And the armament of eight openly standing six-inch guns looked simply ridiculous against the background of two 210-mm and eight 150-mm cannons located in the casemates and turrets of the German armored cruisers of the Victoria Louise type - these are the cruisers that the Dianas would have to fight with in the Baltic in in case of war with Germany...

In other words, the attempt to create an armored cruiser capable of performing the functions of a scout for a squadron and, at the same time, “pirating” in the ocean in the event of a war with England, was a fiasco. Moreover, the inadequacy of their characteristics was clear even before the cruisers entered service.

The Diana-class cruisers were laid down (officially) in 1897. A year later, a new shipbuilding program was developed, taking into account the threat of a sharp strengthening of Japan: it was planned, to the detriment of the Baltic Fleet (and while maintaining the pace of construction of the Black Sea), to create a strong Pacific Fleet capable of neutralizing the emerging Japanese naval power. At the same time, the MTK (under the leadership of the Admiral General) determined the technical specifications for four classes of ships: squadron battleships with a displacement of about 13,000 tons, reconnaissance cruisers of the 1st rank with a displacement of 6,000 tons, “messenger ships” or cruisers of the 2nd class with a displacement of 3,000 tons and destroyers 350 tons.

In terms of creating armored cruisers of the 1st rank, the Maritime Department took a rather logical and reasonable step - since the creation of such ships on its own did not lead to success, it means that an international competition should be announced and the lead ship should be ordered abroad, and then replicated in domestic shipyards, thereby strengthening the fleet and acquiring advanced shipbuilding experience. Therefore, the competition put forward significantly higher tactical and technical characteristics than those of the Diana-class cruisers - MTK formed an assignment for a ship with a displacement of 6,000 tons, a speed of 23 knots and an armament of twelve 152-mm and the same number of 75-mm mm guns. The thickness of the armored deck was not specified (of course, it had to be present, but the rest was left to the discretion of the designers). The conning tower was supposed to have 152 mm armor, and the vertical protection of the elevators (feeding ammunition to the guns) and the bases of the chimneys was 38 mm. The coal reserve had to be at least 12% of the normal displacement, the cruising range was not less than 5,000 nautical miles. The metacentric height was also set with a full supply of coal (no more than 0.76 m), but the main dimensions of the ship were left to the discretion of the competitors. And yes, our specialists continued to insist on using Belleville boilers.

As you can see, this time MTK did not focus on any of the existing ships of other fleets of the world, but sought to create a very powerful and fast cruiser of moderate displacement that had no direct analogues. When determining the performance characteristics, it was considered necessary to ensure superiority over the Elswick cruisers: as follows from the “Report on the Naval Department for 1897-1900,” domestic armored cruisers of the 1st rank were to be built: “like Armstrong’s fast cruisers, but superior their displacement (6000 tons instead of 4000 tons), speed (23 knots instead of 22) and the test duration at full speed increased to 12 hours.” At the same time, the armament of 12 rapid-firing 152-mm cannons guaranteed it superiority over any English or Japanese armored cruiser of similar or smaller displacement, and its speed allowed it to escape from larger and better armed ships of the same class (“Edgar”, “Powerfull”, “ D'Entrecasteaux”, etc.)

As a matter of fact, this is how the story of the creation of the cruiser “Varyag” begins. And here, dear readers, a question may arise - why was it necessary to write such a long introduction, instead of immediately getting to the point? The answer is very simple.

As we know, a competition for designs for armored cruisers of the 1st rank took place in 1898. It seemed that everything should have gone as planned - many proposals from foreign companies, selection of the best project, its modification, contract, construction... No matter how it goes! Instead of the boring routine of a well-established process, the creation of “Varyag” turned into a real detective story. Which began with the fact that the contract for the design and construction of this cruiser was signed even before the competition. Moreover, at the time of signing the contract for the construction of the Varyag, no cruiser project yet existed in nature!

The fact is that soon after the competition was announced, the head of the American shipbuilding company, Mr. Charles Crump, arrived in Russia. He did not bring any projects with him, but he undertook to build the best warships in the world at the most reasonable price, including two squadron battleships, four armored cruisers with a displacement of 6,000 tons and 2,500 tons, as well as 30 destroyers. In addition to the above, Charles Crump was ready to build a plant in Port Arthur or Vladivostok, where 20 destroyers from the above 30 were to be assembled.

Of course, no one gave such a “piece of the pie” to Ch. Crump, but on April 11, 1898, that is, even before the competitive designs of armored cruisers were considered by the MTK, the head of the American company, on the one hand, and Vice Admiral V.P. Verkhovsky (head of GUKiS), on the other hand, signed a contract for the construction of a cruiser, which later became the Varyag. At the same time, there was no design for the cruiser - it still had to be developed in accordance with the “Preliminary Specifications”, which became an annex to the contract.

In other words, instead of waiting for the project to be developed, reviewing it, making adjustments and changes, as has always been done, and only then signing a construction contract, the Maritime Department, in fact, bought a “pig in a poke” - it signed a contract that provided development of a cruiser project by Ch. Crump based on the most general technical specifications. How did Ch. Crump convince V.P. Verkhovsky is that he is capable of developing the best project of all that will be submitted to the competition, and that the contract should be signed as quickly as possible so as not to waste precious time?

Frankly speaking, all of the above indicates either some kind of childish naivety of Vice Admiral V.P. Verkhovsky, or about the fantastic gift of persuasion (on the verge of magnetism) that Ch. Crump possessed, but most of all it makes you think about the existence of a certain corrupt component of the contract. It is very likely that some of the arguments of the resourceful American industrialist were extremely weighty (for any bank account) and could rustle pleasantly in the hands. But... not caught - not a thief.

Be that as it may, the contract was signed. On what happened next... let's just say, there are polar points of view, ranging from “the brilliant industrialist Crump, with difficulty making his way through the bureaucracy of Tsarist Russia, builds a first-class cruiser of breathtaking qualities” and to “the scoundrel and swindler Crump tricked and bribed the Russian Imperial Navy a completely worthless ship." So, in order to understand, as impartially as possible, the events that happened more than 100 years ago, the dear reader must imagine the history of the development of armored cruisers in the Russian Empire, at least in the very shortened form in which it was presented in this article .

To be continued…

History of creation

By the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, the Russian Empire was in dire need of a strong fleet in the Pacific Ocean. The eastern borders of the state reached the Sea of Japan. And on the shores of the Yellow Sea, Russia received a lease from China over vast territories of Manchuria, including the ice-free Port Arthur. At the same time, Japan laid claim to these territories, actively developing its navy. To protect its interests and new territories in the region, Russia began to accelerate the construction of ships . Our own shipyards were not enough for this, and many ships were ordered abroad.

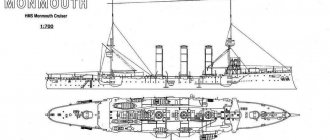

The cruiser "Varyag" was laid down in 1898 at the shipyard of the American company William Cramp and Sons in Philadelphia. On October 31, 1899, it was launched , and in 1900, as part of the contract, it was transferred to the Russian Empire. In 1901, the Varyag entered service and was based in Port Arthur.

The ship was built according to a design similar to the designs of cruisers such as Kasagi and Diana. Some developments in the design and construction of the Varyag were taken into account in the development of the high-speed American cruiser St. Louis. According to the documentation, the Varyag was supposed to have a speed of 23.2 knots. But the initially unsuccessful design of the Nikloss boilers, a number of defects during construction, as well as the weak repair base of Russian ports led to the fact that after just a few years of service, the Varyag could not reach a speed of over 14 knots. This fact practically negated the advantages of the cruiser.