Photo: Tula State Weapon Museum

February 15 marked the 150th anniversary of the birth of Ivan Alekseevich Pastukhov, a Tula gunsmith and machine gun production specialist. Under his leadership, the assembly of the first machine guns was organized in Tula, and together with another famous gunsmith Pavel Tretyakov, he worked on the Russian version of the famous Maxim machine gun.

In total, more than 200 innovations were introduced into the foreign version. So the creation of Hiram Stevens Maxim turned into his faithful comrade “Maximka”. And both gunsmiths earned such great authority that a saying was made about them: “God knows machine guns, Tretyakov and Pastukhov.”

The Russian history of the world's first machine gun and the contribution of Tula gunsmiths to its modernization is in our material.

Machine gun from the creator of the light bulb

Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim, the "father" of one of the world's first machine guns, was a passionate inventor who was interested in a wide variety of technology. In addition to outstanding weapons, he invented a unique smokeless gunpowder, argued with Thomas Edison for primacy in creating the incandescent lamp, and at the end of his life he built giant airplanes. However, the inventor’s main brainchild, the Maxim machine gun, did not immediately gain recognition.

In Sir Maxim's homeland, the USA, the machine gun created in 1883 did not arouse enthusiasm. Then the inventor moved to the UK and devoted about ten years to promoting a new weapon, the firing of which was initially considered a pointless waste of ammunition. Gradually, especially standing out against the background of other automatic weapons, the Maxim machine gun is gaining popularity, and its combat use begins. The inventor personally demonstrates his weapons in European countries, including Russia - in 1888, Emperor Alexander III observed machine gun fire.

Hiram Stevens Maxim with his machine gun

It is unknown what impression the firepower of the machine gun made on the autocrat, but since 1899, the Maxim, adapted first for the cartridges of the Berdan rifle, then for the cartridges of the Mosin rifle, has entered service with the artillery of the Russian army. Why exactly to the artillery? Because the weight of the original weapon was about 250 kg, and when fully equipped, the Maxim rather resembled a cannon.

In the Russo-Japanese War, “Maxims” showed their full potential. The army's needs for heavy machine guns are growing, but purchasing abroad was not cheap, and in 1902 Russia bought the right to its own production from Hiram Maxim and his partners. The Tula Arms Plant was chosen as the site for localization; the head of the tool workshop, Pavel Tretyakov, and the senior foreman, Ivan Pastukhov, were sent to the UK to get acquainted with the technology. This is how the story of the “Russification” of the Maxim machine gun begins.

Joseph Montigny's first card game

Meanwhile, already at the beginning of the 19th century. A technical revolution began in Europe, steam-powered machines appeared, and the accuracy of the parts produced on them increased sharply. In addition, unitary cartridges were created that combined gunpowder, primer and bullet into a single ammunition, and it was all this together that led to the appearance of mitrailleuse or grapeshot. This name comes from the French word for buckshot, although it should be noted that the buckshots themselves did not shoot with buckshot, but with bullets, but this was already the case from the very beginning, since the very first mitrailleuse, which was invented in 1851 by the Belgian manufacturer Joseph Montigny, and France adopted it into service with its army. Enviable ingenuity

It must be said that Montigny showed great ingenuity, since the weapon he created was distinguished for that time by very good fighting qualities and the originality of the device. She had exactly 37 13-mm caliber barrels, and all of them were loaded simultaneously using a special plate-clip with holes for cartridges, into which they were inserted and held by the edges. The plate along with the cartridges had to be inserted into the grooves behind the barrel, after which they were all pushed into the barrels with a special lever, and the bolt itself was locked tightly.

To start shooting, you had to twist the handle installed on the right side, and it, through a worm gear, lowered down a special plate that covered the firing pins installed in front of the cartridge primers. At the same time, special spring-loaded rods hit the strikers, which is why the shots followed one after another as the plate lowered. This happened because its upper edge had a stepped profile, and the rods jumped out of their sockets and hit the strikers in a certain order. An experienced crew could replace the plate with a new one within five seconds, which made it possible to achieve a rate of fire of 300 rounds per minute. But even a more modest figure of 150 rounds per minute was an excellent indicator at that time. In another version of this mitrailleuse designed by Verchères de Reffi, the number of barrels was reduced to 25, but its rate of fire did not change.

Mitrailleuse de Reffi from the Army Museum in Paris

Mitrailleuses were used by the French during the war with Prussia in 1871, but without much success, since the weapon was new, and they simply did not know how to use it correctly.

“God knows machine guns, Tretyakov and Pastukhov”

The Tula ambassadors studied the experience of British gunsmiths for a month and a half and came to the conclusion that the production of Maxim machine guns could be organized at their home plant without serious difficulties. The first prototype of the Russian Maxim was ready at the end of 1904, and in May of the following year the machine gun went into production. The serial sample number 1 is still kept in the Tula Arms Museum.

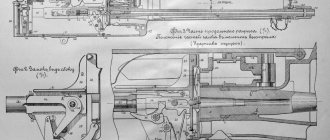

The heavy weight of the machine gun made it difficult to use, and gunsmiths Pastukhov (pictured on the left) and Tretyakov (pictured below) set about refining the basic model. One Maxim machine gun consisted of 282 parts, and its creation included 2,448 precision operations. The engineers faced a difficult task, but they managed it.

Tula craftsmen managed to significantly lighten the Maxim, increasing the range and reliability of the weapon. In total, about 200 changes were made to the machine gun. In 1905, a British representative who visited Tula noted that the Russians were able to achieve interchangeability of machine gun parts, which was not yet available in Europe.

The further history of the Russian “Maxim” is the history of its modernizations. In 1908, Vickers demonstrated its lightweight version of the machine gun, weighing 11.36 kg. However, Tretyakov and Pastukhov again beat the British, presenting their lightweight Maxim, which turned out to be more advantageous. It was put into service under the designation “Maxim heavy machine gun mod. 1910" with a completely original machine designed by Tula gunsmith A.A. Sokolov. The weight of the Maxim with the machine and cooling liquid was 67.6 kg. It was in this version that the machine gun acquired its familiar appearance.

It should be noted that the British also began to actively use Russian developments in their modernizations. They even try to produce the Russian modification in England, where Ivan Pastukhov is sent for acceptance, but the British disrupt deliveries, and the Imperial Tula Arms Factory remains the only manufacturer. In total, until 1914, 4,782 Maxim machine guns in all modifications were manufactured in Russia.

Photo of the PKM machine gun

Kalashnikov PKMS machine gun on a 6T5 machine designed by Stepanov

The butt plate of the PKM stock (on the right) is equipped with a folding shoulder pad, designed for more rigid fixation of the machine gun when firing

Slotted machine gun flash suppressors (from bottom to top): PK, PKM of early releases, PKM currently in production

PKS machine gun (PK on a 6T2 Samozhenkov machine) with an ammunition box with a belt for 250 rounds

“A machine gunner scribbles for a blue handkerchief”

Russia met the First World War with a single machine gun of its own production - the Russified "Maxim" of the 1910 model. The soldiers were captivated by the simplicity and reliability of the weapon. The machine gun became a faithful comrade, gradually changing the emphasis in the creator’s surname to the Russian version, and later even becoming a native “Maksimka”. One of the results of the First World War was the recognition of the machine gun as the most powerful infantry fire weapon.

During the Civil War, the Maxim also remained the main type of machine gun. It was during these years that the cart, a horse-drawn spring cart with a machine gun directed against the direction of travel, became widespread, combining the power of machine gun fire with cavalry speed.

Commanders and soldiers of the Red Army with a Maxim machine gun, late 1920s - early 1930s

In the 1920s, new requirements were put forward for machine guns and another modification of the Maxim was brewing to improve its combat qualities. Modernization of the machine gun became one of the main tasks of the new design bureau at the Tula plant. This version was called the “Maxim machine gun model 1910/30”.

Throughout the Great Patriotic War, “Maxim” faithfully served Russian soldiers. The machine gun, which was obsolete by that time, nevertheless remained the most reliable and, in some respects, was even better than newer models. It was used by infantry and mountain riflemen, and was installed on ships, cars and armored trains. There was even a quadruple anti-aircraft gun from the Maxims for firing at low-flying aircraft.

Soviet soldiers prepare a Maxim machine gun for anti-aircraft fire

Only in 1943 did the Goryunov machine gun replace the Maxim. The Maxim machine gun was produced until the end of the war and was then used for many years in different countries. It is believed that the last time this legendary machine gun was used was in 1969 in the Soviet-Chinese border conflict on Damansky Island. Thus ended the glorious history of the Russian “Maxim”, which became not only a weapon of Victory, but also a part of mass culture.

Finally, it is worth mentioning once again the creators of the Russian version of the machine gun. At the height of the First World War, Pavel Petrovich Tretyakov was appointed head of the Tula Arms Plant, and after the October Revolution of 1917 he remained at TOZ as head of the machine gun department. In 1927, Pavel Petrovich became the organizer and head of Russia's first design bureau for the development of small arms, the future KBP named after. A.G. Shipunova. Within the walls of the new enterprise, the modernization of Maxim machine guns continued.

After the revolution, Ivan Alekseevich Pastukhov continued to work at the Tula Arms Factory. In 1926, he was appointed senior designer of the machine gun department, and in 1927 he was transferred from TOZ to PKB. According to the memoirs of another outstanding gunsmith F.V. Tokarev, “Pastukhov was a living reference on Maxim, an expert on its technology, tools, drawings and approval.” In addition to gunsmithing, Pastukhov had a lot of hobbies: floriculture, beekeeping, skiing, photography.

From “electricians” to machine gunners

The story of the hero of our story began back in 1866, immediately after the end of the bloody American Civil War. During the fighting, multi-barrel canisters, or, in the French manner, mitrailleuses, were actively used. The most popular was the famous Gatling system. But this was only a prototype of a full-fledged automatic machine gun.

Hiram Maxim and his brainchild

Source: pinterest.ru

That year, 26-year-old aspiring inventor Hiram Stevens Maxim, who found himself in the company of Southern veterans, had the opportunity to fire shots from a Springfield musket, the main infantry weapon of the last war. At that time, Hiram Maxim had not yet thought about a career as a gunsmith, but, apparently, his interest in weapons appeared right then.

The real dream of a young inventor is to invent something related to electricity and electrical engineering. This direction was also new at that time, and the invention promised enviable prospects. For a long time he was in a company that competed with the company of Thomas Edison himself, but the connections of competitors did not allow Maxim to push his own inventions. All this time he worked on the drawings of what he later called a machine gun.

The first machine guns were very cumbersome

Source: pinterest.ru

That meeting with the veterans of the South at the shooting range was remembered not only for the friendly atmosphere. Maxim remembered the unpleasant sensations from the enormous recoil of the Springfield musket, and he came up with the idea of using the excess recoil to reload the weapon. This is how the barrel bore locking mechanism appeared. The introduction of tape feeding was also an innovative solution.

Military use and place of the Gatling gun in history

The first products off the assembly line were sent to equip ships of the American navy. The main purpose of the Gatling guns on ships was to combat mine boats and mines. After this, the system became widespread in the armies of other countries, which also felt the need for rapid-fire weapons. However, the invention of the American designer never became widespread. The army's skepticism about this was reflected in the fact that the cannon, rifle and cavalry are the main means of armed struggle on the battlefield. The high cost of the machine gun also affected it. For example, each machine gun cost the customer $1,000, while a rifle cost only $15-20, and revolvers even less.

Unlike the Americans, who were entirely busy re-equipping their army with new guns and rifles, the British showed interest in the Gatling gun. Their colonial troops were in dire need of new firepower that could effectively counter the native armies.

Small contingents of British troops fought a difficult battle against the superior native forces. In this case, automatic weapons could become a lifesaver. The Gatling gun was used effectively by British troops during the suppression of the Zulu Rebellion. The British, armed with two machine guns, managed to push back the crowd of advancing Aborigines in a matter of minutes. The effect produced was stunning both for the British themselves and for the vanquished.

The successful use of machine guns by the British in the colonial wars gave rise to the massive rearmament of armies. Machine guns were successfully used during the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-78. Moreover, a certain number of weapons were produced directly in Russia, which received permission for the industrial production of Gatling’s brainchild. The machine gun was actively used by both colonialists in the fight against tribes, and by the police, using machine guns in suppressing mass labor protests.

As a result of active use, the machine gun underwent a certain modernization, which boiled down to an increase in the rate of fire. Thus, the five-barreled machine gun of 1876 had a rate of fire of 800-1000 rounds per minute. In other words, each barrel could fire up to 200 bullets per minute. The receiver of the Gatling machine gun, the American Vulcan aircraft cannon, boasts similar characteristics. Nearly 100 years after the Gatling gun became a milestone in the history of automatic weapons, gunsmiths have returned to the idea developed by an American doctor.

PREDECESSORS

PREDECESSORS

We can say that the “struggle for rate of fire” began already at an early stage in the development of firearms. The further weapons and their ammunition developed, as well as the production technology of both, the more firearms penetrated into military affairs and other branches of human activity - and, accordingly, the greater the demands placed on weapons by “users” - the more sophisticated techniques were developed to increase the rate of fire.

Of the various ways to increase the rate of fire, several can be distinguished: increasing the number of barrels (with simultaneous or sequential firing from them), increasing the number of chambers with one barrel, increasing the number of charges in one barrel, moving to a breech-loading circuit, combined options.

Increasing the number of barrels was the simplest option from a technical and technological point of view, and therefore was used relatively widely. Here we can recall the European multi-barrel “organ” guns, which were used mainly in serf warfare. In field battles, the loading time - and therefore the low rate of fire of hand-held firearms - was already compensated for in the 16th century by salvo fire from ranks of riflemen, but in fortress or mountain warfare, when fighting in narrow areas, such a technique was not suitable. So the idea of putting many rifle - or slightly larger - caliber barrels onto one installation was born quite naturally. In Russia, such weapons in the 16th - early 17th centuries were called “magpies”. In some systems, small caliber barrels were arranged in horizontal rows around the circumference of an impressively sized drum. The row in which the barrels were directed towards the enemy fired a volley at the enemy, the drum turned, the next row fired a volley, and so on until the ammunition was completely used up. The Russian pioneer Ivan Fedorov, who was also a cannon master, in 1583, shortly before his death, demonstrated a collapsible multi-barreled gun. From individual parts it would be possible to “make cannons that destroy and destroy the largest fortresses and well-fortified settlements,” as Fedorov himself wrote. The number of barrels and the size of the gun would depend on the task. Thus, the pioneer printer was perhaps among the first to use a modular design in the design of guns. However, loading such “guns,” like “organs” and “magpies,” was a long and tedious process, and “quick” shooting was not always achieved due to various failures. By the beginning of the 18th century, “organs” left the scene. True, projects are still coming. Thus, in 1739, the arms adviser of the Tula plant, Andrei Behr, presented Field Marshal Minich with a model of a certain “figure invented from the head,” which was a multi-barreled weapon made up of several guns and locks with a device for simultaneous operation. The gun had to be placed on carts, have one row of gun barrels for firing a bullet or two - the lower one was a large-caliber gun for firing buckshot, the upper one was a “soldier’s barrel for firing a bullet.” The St. Petersburg Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps houses a “quick-fire battery” developed in 1741 by mechanic A.K. Nartov - a circle is installed on a two-wheeled carriage, along the rim of which 44-three-pound (76 mm) mortars are placed. The very idea of installing several barrels on a rotating wheel was not new for the 18th century, but here mortars fired in groups, and after each salvo the wheel turned automatically. In 1743, a Russian agent in Danzig recommended that the government take up the “invention” of a certain artilleryman Goetsch, which involved a set of gun barrels mounted in a box on a gun carriage. This machine, like Baer’s “figure,” was supposed to “be in the regiments,” that is, serve as a regimental weapon. According to the statement of the Feldzeichmeister-General, “his Götsha test of the inventions was carried out and turned out to be very unsuitable.” Already in 1823, a mechanic from Vienna, Schuster, presented to the Chief of the General Staff, Adjutant General Volkonsky, a project for a “rapid-firing machine” for firing at a speed of “from 100 to 120 gun shots per minute in a parallel direction,” with the shooter “sitting on the machine itself.” , had to rotate the handle. None of these inventions yielded practical results. But multi-barreled hand weapons - pistols, shotguns, rifles - found sales.

One of the ancestors of buckshot and machine guns is the 105-barreled “organ” (“battery”). End of the 17th century. Military Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps, St. Petersburg

The end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th century was the time of transition in firearms from percussion flintlocks to percussion caps, as well as another surge of interest in increasing the rate of fire. By this time, quite successful revolver schemes had been developed. The most interesting search structures were created by the Swiss I.S. Paulie (Pauli), who worked in France. In his Paris patent of 1812, he, taking advantage of the advent of capsule compositions, proposed a design for a unitary cartridge with a metal sleeve. Poly was half a century ahead of not only the general development of cartridges and weapons, but also production technology, so things simply could not go further than piece samples.

A very original type of multi-shot weapon was the espinole, which appeared back in the 16th century. The basis was a barrel with “overhead charges” - several charges of gunpowder with bullets were placed along the length of the barrel bore, separated by dense wads. To ignite such charges, they could use a through ignition cord, and then they would get something like a queue, several locks along the length of the weapon, or one lock moving along a special guide.

The immediate predecessors of automatic machine guns in the second half of the 19th century were rapid-fire guns known as “cardboxes” or “mitrailleuses”. It is worth remembering their history in the Russian army both because the experience of their use left its mark on the attitude towards machine guns in the early period of their development, and because the word “machine gun” itself was, in fact, first used specifically for grapeshots.

Original (American) 6-barrel Gatling gun

First, about the names. The Russian word “buckshot” appeared as a translation of the French “mitrailleuse” (mitrailleuse, from mitraille - “buckshot”) and reflected the tactical, rather than technical, features of the new type of weapon - it was supposed to replace the action of buckshot, but it fired bullets rather than grapeshot charges. The fact is that with the rearmament of the infantry with rifled weapons, the range of aimed fire by the infantry increased to 850 - 1000 m, which made it difficult for the artillery on the battlefield to reach the range of a grape shot. A new rapid-fire gun with the same effective firing range as a rifle was supposed to provide artillery with the ability to hit the enemy within infantry firing range.

An increase in the rate of fire was achieved by a traditional increase in the number of barrels (from 5 to 25) in combination with innovations - a unitary cartridge and mechanical drive mechanisms. Shooting was carried out in volleys (as in Reffi's grape shotgun) or sequentially. The power supply, locking, trigger, and extraction mechanisms were driven by a rotating (Gatling, Gardner, Monceau) or swinging (Palmkranz, Nordenfeld) handle. According to modern classification, canisters can be classified as “automatic weapons with an external drive,” but since this drive was based on muscular energy, canisters occupied an intermediate position between magazine and automatic weapons.

Palmkrantz's ten-barreled shotgun

The first use of the “cardbox” was found during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. And in 1866, the Russian Ministry of War sent Colonel A.P., a member of the Artillery Committee of the Main Artillery Directorate (GAU), to the USA. Gorlov and the clerk of the Armory Commission, Lieutenant K.I. Gunius. For the Russian Army, this period of reform was marked, among other things, by the transition to breech-loading weapons chambered for a unitary “small-caliber” cartridge with a metal sleeve. After the usual 6-line (15.24 mm), a caliber of about 4 lines, of course, looked “small”.

The task of Gorlov and Gunius was to study American weapons and their production, and most importantly, to select samples for the rearmament of the Russian army. The names of Gorlov and Gunius are associated with the appearance in service of the Russian Army of a 4.2-line rifle cartridge (10.67 mm, with a solid-drawn brass sleeve, a charge of black gunpowder and a lead unsheathed bullet), the Berdan rifle mod. 1870 and canisters chambered for this cartridge, a revolver of the Smith and Wesson system with its 4.2-line cartridge. Of the various canister systems available in the United States at that time, the system of Dr. Richard J. Gatling with a rotating block of barrels, patented in 1862, aroused the greatest interest in different countries. Gorlov was tasked with collecting data on Gatling canisters in the United States. 20 shotguns were ordered from the Colt factory, and Gorlov was instructed to make improvements to them at his discretion. The 10-barrel version was taken as the basis. The main changes made to it by Gorlov were that the barrels were made for the 4.2-liner “Berdanov” cartridge, the bolt and ejector were improved, and operational reliability was increased. In September 1869, twenty 10-barrel Gorlov (more precisely, Gatling-Gorlov) grape guns arrived in St. Petersburg, and were soon put into service under the designation “4.2-line rapid-fire gun.” This "gun" is usually referred to as the "Model 1871".

“Rapid-fire cannon arr. 1871" Gatling-Gorlov system on a light carriage with a limber. The left wheels are not shown. The cartridge stowage is visible

The name “cardbox,” although widely used, was too conventional; the official name “quick-firing gun” soon ceased to correspond to reality, and with the advent of rapid-firing artillery guns with an elastic carriage, it simply gave rise to confusion. This forced the introduction of a new term already in the 1880s - “machine gun”. In its origin, one can also trace the French influence - for grapeshots in the French language, in addition to mitrailleuse, they also used the name canon a'balles, i.e. “bullet gun”. There is nothing unusual in the fact that the word “machine gun” was later transferred to a new, automatic type of weapon - in French the word mitrailleuse was retained to designate an automatic weapon, and the English-language machinegun was also initially applied to grapeshots. The first automatic samples in the USA were called “automatic machine guns”, and in Russia - “automatic card guns”.

In the meantime, the production of “4.2-line rapid-firing guns” of 1871 was installed in St. Petersburg (later - “Russian Diesel”) - this was one of the few examples of mass production in Russia of rapid-firing weapons for the army by a private plant that developed its own machine tool industry ( Ludwig Nobel also supplied machine tools to state-owned arms factories). Unlike the leading industrial countries, the production of military weapons in our country remained the responsibility of primarily state-owned factories. The overall development of mechanical engineering in Russia lagged far behind countries such as Great Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France, and the USA, where precision engineering was actively developed by private companies. Accordingly, the transition to a new weapons system required a new re-equipment of Russian state-owned factories - at public expense and with large purchases of equipment abroad. The own production of precision machine tools also had to be installed at the weapons factories themselves.

Artillery Captain V.N. Zagoskin, based on the Gatling system, created an 8-barrel shotgun chambered for the old 6-line cartridge. The Nobel plant produced only 8 of these canisters, but they worked on production. A.A. Based on the carriage of this canister, Fischer developed a lightweight carriage for the Gorlov canister - before that, a field gun carriage was used.

By that time, the enthusiasm of the rapid-fire supporters had cooled somewhat. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. Reffi's 25-barrel canister batteries were not particularly useful in battle. Nevertheless, in 1871 in Russia, fourth - “rapid-firing” - batteries were formed in artillery brigades, arming them with Gatling-Gorlov canisters. With the transition in 1872 in field artillery to a 6-battery structure of artillery brigades, “rapid-fire” batteries became the sixth in them.

They didn’t forget the 6-barrel Gatling shotgun. Its improvement was carried out by engineer V.S. Baranovsky, and two years after the Gorlovka one, the grape gun arr. 1873 Gatling - Baranovsky. With a lighter carriage and a pair of harnesses, the maneuverability of the buckshot gun increased. It was also important to reduce its crew from 7 to 3 people. The Baranovsky shotgun made by L. Nobel was recognized as the best at the “mitrailleuse show” organized by the Egyptian Khedive (Turkish ruler of Egypt).

This system could already have become “closer” to the infantry and cavalry, but infantry and cavalry officers did not participate in experiments with canisters, issues of their interaction were almost not considered, which contributed to the “narrow specialization” of canisters. In the same 1873, by order of the Commander-in-Chief of the Guards and the St. Petersburg Military District, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich Sr., comparative firing of four grapeshots (“quick-firing guns”) and half a platoon of infantry was carried out at the same targets and from the same ranges. It turned out that “the infantry determined the distance sooner, fired their cartridges sooner” and, moreover, with greater accuracy. In combination with frequent delays in the operation of mechanisms identified by operation, this did not add popularity to hand-held buckshots.