On the verge of normalization and cruelty (in the sense of the outcome of the fight), a duel existed in Russia in the 18th century. Being officially banned since the time of Peter I, it nevertheless remained a part of Russian noble culture for many decades. She was not encouraged, she was punished for it, but at the same time, they often turned a blind eye to her. The noble community, despite all the prohibitions, would not understand and certainly would not accept back a nobleman who refused to defend his honor in a duel. Let's figure out why no self-respecting nobleman could ignore an insult and what distinguished a duel from a murder.

For the nobleman of this era, honor was never an ephemeral concept: along with the special rights assigned to him by status, he also had special duties to the state, but most importantly, to his ancestors. The nobleman had no moral right not to live up to his origin, and since the social component of his life was extremely important, he was constantly under the “supervision” of society, whose judgment was extremely important. For example, according to the unspoken code of honor, unacceptable traits for a nobleman were deceit, cowardice, as well as disloyalty to an oath or a given word.

Honor was a symbol of nobility, and the injured honor of one person was perceived not just as a humiliation of personal dignity, but as an indication that the person was not worthy to belong to a particular clan as a whole. Roughly speaking, the insult to honor was an insult to the memory of ancestors, which cannot be ignored. Initially, duels were precisely intended to restore honor, but over time, as Yu.M. writes. Lo, turned into a real “ritualized murder.”

Thus, the Russian duel is a ritual of conflict resolution that existed in a fairly limited period of Russian history, from the mid-18th to the mid-19th centuries.

Initially, a duel was viewed as a violation of public peace and order, lynching and an insult to authority, but by the 19th century it turned into a private crime, that is, an attempt on the life and health of a specific person. Society's attitude towards her was different. Most of the nobility perceived the duel as a given, a kind of legacy that did not depend on personal opinion and will. It allowed the nobles to almost physically feel their honor, and, up to a certain time, it supported in them a sense of responsibility for their actions. Well, the bloodthirstiness of the duel, as a rule, was condemned only by old men and women, that is, by those who did not take direct part in it.

A matter of honor

History knows many types of private duels - knightly tournaments, “funny fights”... But a duel has a number of features that distinguish it from other fights.

Heiress of the tournament

It is believed that duels appeared in Europe in the 16th century - after the extinction of knightly tournaments. Their homeland is Italy, but soon the tradition of personal duels spread to France and Germany.

“Duo” means “two,” but duels were not always paired. At the initial stage, there are many fights between large companies. In France, there is a known case of 6 opponents fighting at the same time, and only one survived.

A. Dumas used the precedent to create the final scene in “The Countess de Monsoreau”. But already in the 18th century, duels became a duel between two.

The history of duels in Russia began in 1666. It was an import - the participants were two foreign hired officers. The winner, Patrick Gordon, then became a prominent figure in the Peter the Great era.

Features

In past centuries, a “private” fight was not considered something special. But the duel had a number of characteristics unique to it.

- The reason for the duel is an insult to the honor and dignity (of the participant or a woman close to him). A property dispute or criminal claim was considered by the court.

- A duel is an armed duel. Fighting without weapons was not considered such.

- The challenge and the fight itself had to have witnesses. Meetings in private were rare.

- Opponents were given equal opportunities: the same weapons and conditions. For this reason, before the fight, new weapons were necessarily purchased. Each participant had to have a set “for two”, and whose would be used was decided by lot. If one of the opponents could not fight (was old or sick), he could nominate a deputy (usually a relative or best friend). Such a case is described by Corneille in the Cid.

- The goal was not to kill the enemy, but to prove one’s moral superiority. Although murders were not uncommon.

- Only a duel of equals could be considered a duel. Although they didn't have to be nobles.

- The fight had to have a protocol. This was required to ensure that the participants could not be considered criminals. The protocol could be “on parole,” but more often it was written down.

These were unwritten rules, but they were strictly followed. There were deviations, but more often by agreement of the parties.

Commoner's honor

Usually the participants in the fights were nobles, especially officers. But this was not an immutable rule. For example, the famous Russian politician of the beginning of the last century A.I. Guchkov (of a merchant family, but received nobility according to the Table of Ranks) was known as the most dangerous breter (that is, a fighter).

In Western Europe, student duels have long been extremely popular.

They fought with swords. The participants sought to inflict a wound on the enemy, very lightly, but in a noticeable place, preferably in the face. The goal was not so much to punish the enemy for insulting him, but to prove that you are a fighting guy, and it is better not to touch you.

The more scars a student had on his face, the more he was respected. One thing is important: the opponent of the nobleman was the nobleman, the commoner was the commoner. In Western Europe (but not in Russia), women's duels have been recorded.

Reasons for the duel

It was up to the person offended to decide how much honor was damaged and whether the insult was worth killing, but society identified the main reasons for the conflict, which could escalate into a duel.

- Differences in political views are the least common cause of conflict in Russia; nevertheless, clashes on political grounds periodically occurred with foreigners, but the state monitored “international” duels much more strictly, so they did not happen so often.

- Service conflicts that began on the basis of service were more severe in nature, since almost every nobleman served in Russia. For many, service became an end in itself, so to humiliate service achievements or doubt them meant hurting honor. Such duels, however, were not particularly widespread.

- Defense of regimental honor can be considered as a separate reason for the duel: it meant too much to the officers, so the slightest ridicule required retaliatory action. Moreover, defending the honor of the regiment was an honor.

- Protection of family honor - any insult to a person belonging to a particular family was regarded by members of the clan as a personal insult. Insults inflicted on deceased relatives, women and the elderly, that is, those who cannot stand up for themselves, were particularly acute.

- At a separate level was the protection of a woman’s honor. And if unmarried girls tried to protect themselves from duels associated with their name (a stain on their reputation), then many married women did not mind being in the center of attention, sometimes deliberately provoking their husbands and lovers into clashes. To insult a woman’s honor, specific actions were not necessarily needed - a hint was enough, especially if it was hinted at an unacceptable relationship of a married woman, which, naturally, cast a shadow on her husband. It was impossible to ignore this.

- Rivalry between men over a woman is also a different story: the conflict usually flared up over an unmarried girl, who, however, already had suitors. If both men had designs on the same woman, a clash between them was inevitable.

- Protecting the weak. A particularly heightened sense of honor forced the nobleman to suppress any attempts to humiliate the dignity of the nobility as a whole. If a nobleman allowed himself to insult the “weak” (for example, a person at a lower level of the social hierarchy), another could act as a noble defender and punish the offender for unworthy behavior.

- However, domestic quarrels remained the most common. Since among the nobility the ability to behave properly was considered one of the fundamental features of noble upbringing, a nobleman who dared to behave unworthily seemed to offend the honor of the entire nobility in general and each nobleman individually. Special areas of everyday life predisposing to duels were hunting, theater, racing, gambling and other activities involving a competitive spirit.

The right to choose

It was always provided to the participants in the duel. How much depended on their status. We chose a weapon, a place, a method of action. The offended person had more rights, but everything depended on the severity of the conflict.

One of the participants could refuse the fight. But this was fraught with consequences. Without them, only the offended, having received an apology, recalled the call.

A cowardly offender could be boycotted or fired from service. The presence or absence of a ban on dueling did not play a role.

There were exceptions. Thus, the famous gunsmith S.I. Mosin twice sent a challenge to the husband of his beloved woman, and both times he... reported a potential enemy to the appropriate authorities!

Weapon Selection

This right was granted to the offended. Until the 18th century, bladed weapons were usually used - saber, rapier, sword. The blades had to be of equal value, the same length or taking into account the height of the fighters. There were mentions in history of oddities, such as the use of candelabra.

19th century dueling codes favored pistols. Only new, identical in characteristics, smooth-bore samples were used.

After the meeting, the opponents could keep the weapons for themselves. But they no longer had the right to fight him again. Sometimes they agreed on the use of several types of weapons.

Selecting a location

Except for particularly severe cases, this issue was resolved jointly. A fairly well-known, but deserted and remote place was required. Therefore, there were areas where duels took place regularly (Pré-au-Claire in Paris or the same Black River).

If the offense was very serious, they could use a place that was dangerous for the fallen person (the seashore or an abyss). Then even a slight wound threatened opponents with death.

But this happened infrequently; during a duel, the main goal was rarely to kill. You couldn't be late for the fight. A delay of a quarter of an hour was considered evasion.

To the barrier

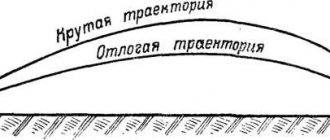

We also had to choose a way to conduct the fight. It was possible to fight with edged weapons while standing still or moving, as in a normal battle. Pistols provided even better room for maneuver. There were several possibilities for using them.

- Stand motionless and shoot at a signal from a certain distance (measured in steps).

- Stand motionless with your back to the enemy and shoot over your shoulder at random.

- Disperse a certain number of steps, and then, on command, converge to a certain point. The shot could be made at this mark (barrier) or on the move.

- Converge gradually, making the agreed number of stops to shoot. Moreover, each enemy who had already fired a bullet had to wait until the second one did the same.

- Load only one pistol, choose a weapon by lot, put the muzzles to each other's foreheads and pull the triggers. How will fate decide...

There were other options. Thus, in America, “hunts” were practiced, when opponents with the same weapons (they were previously searched) were launched into a certain place (a ravine, a grove, a house). They could do whatever they wanted there until the charges ran out.

This is what the duel between Maurice Gerald and Captain Colquhoun looks like in The Headless Horseman. In serious cases, Russians shot “through a scarf.” The distance was determined by the length of the outstretched arms of the participants, grasping the corners of one handkerchief. It was impossible to miss.

Judicial duels: waist-deep in a pit and holding a ram's horn in hands

The books were equipped with gorgeous engravings, from which we can judge the weapons and armor in such fights. An excellent example is the book of the master Hans Talhoffer, who in the 15th century published an excellent textbook on martial arts. Judging by his engravings, each of the opponents was dressed in a tight-fitting cloth or leather jumpsuit, covering, among other things, his head. The man was armed with a wooden club, the top of which was shaped like a diamond. The woman held in her hand a stocking in which a heavy stone was placed. In addition, the man had to fight waist-deep in a pit.

Modern reconstruction makes it clear that everything was tough and uncompromising in the medieval way

Without bureaucracy

The stages of the duel were necessarily documented. The challenge had to be made publicly (by cursing the enemy, throwing a glove in his face, or slapping him in the face) or in writing.

If one person received several challenges, a strict lot was held, or the person summoned chose his own opponent (to prevent reprisals from many against one). The terms of the meeting were also written down and signed by the participants.

This was to prevent crimes under the guise of honor duels. Sometimes this rule was violated at the risk of the participants. More often this was done when they were going to fight to the death, or in the era of the prohibition of skirmishes. There were also disguised murders - the criminal called out an obviously weaker enemy.

Mandatory participants

Although only 2 people were supposed to participate in the battle itself, there were usually a lot of people at the place where the duel took place. Witnesses kept order and provided assistance to the participants.

Ambulance

If death was not expected, the presence of a doctor was required. Sometimes they brought two - from each side. During the era of banning fights, it was agreed that doctors would not tell the authorities the true cause of their patients' injuries.

Doctors had to save the lives of those seriously injured and determine whether the wounded fighter could continue the fight. They often confirmed death...

Be my second

The most important participant in the duel is the second. This person usually became the best friend or relative of the participant, and was not directly related to the conflict.

Once a challenge had been issued, the opponents should not communicate. All negotiations were conducted by seconds (1-2 from the side). They also had to check the weapons, measure the distance if necessary and monitor the opponents' compliance with the rules.

Sometimes a steward (the most senior and respected among the seconds or simply a respectable person) was selected from among them or additionally. The manager checked that there were no violations, did everything necessary to reconcile the warring parties, and gave signals for the beginning and end of the fight.

It was not safe to be a second. Anti-dueling laws punished them almost as severely as the participants. There have been worse cases. So, in 1870 in Paris, Prince Pierre Bonaparte, a cousin of Emperor Napoleon III, shot and killed 20-year-old journalist Victor Noir.

The young man came to him as a second for his friend, Pascal Grousset (known as a friend and co-author of J. Verne, writer Andre Laurie). He challenged the prince to a duel for grossly insulting the Corsican socialists (Grousset was a Corsican and a revolutionary). The dueling code is not criminal. The prince was acquitted...

Franz von Bolgar

1. The challenge can be made now after the insult has been made or after.

2. If the call follows immediately, then the caller must convey the name and address to the caller, to which the latter responds in kind. Then both choose their seconds and send each other their names and addresses.

3. The challenge that follows can be made in words or in writing and is always conveyed to the person being called by the caller’s seconds.

The verbal challenge should be short and should state the cause simply and clearly.

A written challenge should not deviate in form and content from the customs accepted in an intelligent society, and is always read in advance by the seconds.

4. When called, seconds do not have the right to have any weapons with them; only officers remain with the bladed weapons assigned to them.

5. When transmitting a call, seconds should avoid any discussion with the opponent and demand an answer immediately. If the latter nevertheless began to go into explanations, then they should now leave and draw up a protocol about it.

6. The summoned person must receive his opponent’s seconds politely*, listen to them without interrupting and announce his decision immediately. Upon accepting the call, he then sends them the names and addresses of his seconds; in case of refusal on his part - motivated or not - the seconds must draw up a protocol about it.

7. Opponents are not allowed to have any relations with each other from the challenge until the termination of their case. It would be a reprehensible rashness if they came together even before negotiations between the seconds and agreed on the terms of the duel, since, despite their mutual agreement, they would still have to submit to the determination of the seconds.

8. Opponents must not have relations with the seconds of the other side.

9. A call on behalf of more than one person is always rejected.

10. Challenge is not allowed between father and son and between brothers.

11. The debtor cannot call the lender until he has completed accounts with him. Summoning the debtor by the lender is allowed.

12. The call may not be accepted:

a) from a person about whom everyone knows that he violated the rules and conditions of the duel;

b) from a person about whom everyone knows that he, as a second, took part in non-compliance with the rules and conditions of the duel or agreed to violate them intentionally;

c) from a person who, as everyone knows, committed an act contrary to the concept of honor*.

13. Anyone offended, bringing a complaint against the offender, is deprived of the right to demand knightly satisfaction. He loses this right even when he withdraws the complaint; however, in the latter case, the offender is given the right to accept the challenge or not.

14. The call must be made no later than 24 hours after the insult was inflicted.

The same period is determined for the answer, counting from the time the call was received

Decelerations can only be taken into account when they are quite substantial

15. Unless special complications arise and the seconds, for good reasons, decide otherwise, the duel must take place within 48 hours following the time the challenge is accepted.

16. Between officers located in the theater of military operations, cases concerning insult to honor are resolved no earlier than after the conclusion of peace.

The ban is not a hindrance

In the 17th century in Europe, duels became so widespread that they began to significantly reduce the number of nobility. Related to this are attempts to get rid of them. The attempt made by Cardinal Richelieu is quite well known.

What happened to him was exactly what is described in “The Three Musketeers” - the number of fights only increased.

There was even an impudence that, out of principle, he arranged a duel right under the windows of the formidable minister. The insolent man was executed, but the nobles continued to fight, if only to spite the cardinal.

Petrovsky Charter

Peter the Great was in no hurry to import its shortcomings from Europe. A special charter prohibited them from fighting in Russia under penalty of death for all participants!

It turned out no better than Richelieu's. The nobles still considered it, in many cases, a matter of honor to wash away an insult with blood.

The law prohibiting fights was applied several times, but was able to only slightly reduce their number.

Subsequently, Russian emperors repeatedly made attempts to stop these outrages in Russia, but with the same success. Catherine II threatened to exile the bullies to Siberia - and only slightly reduced the number of fights. Nicholas I was a resolute opponent of duels, but during his reign Pushkin and Dantes and Lermontov and Martynov fought.

Society did not support the rulers on this issue. The duelists were helped to disguise the fights, senior officers tried to get rid of subordinates who evaded satisfaction, and their comrades obstructed them, forcing them to resign.

Exile to the active army or demotion to soldiery, practiced as punishment for a duel in the mid-19th century, was perceived by many as a reward, recognition of courage. Such “punished” people received ranks and orders faster than others. There were also fans of duels among the emperors, for example, Paul I.

Mandatory battle

Emperor Alexander III took a different path. In 1894, he lifted the bans and introduced official rules for organizing duels among officers. Any dispute had to be first considered by the officers' council. If he ruled that it was better for the opponents to make peace, they might obey, or they might not.

If it was decided that a fight was obligatory, the one who refused was immediately dismissed from the army.

This decision increased the number of duels, but not the number of deaths. In general, in Russia, shooting intentionally past, or even into the air, was considered a worthy deed. Alexander's decrees were abolished along with the monarchy.

Dueling fever

The era of Alexander I is rightly considered the golden age of the Russian nobility - and at the same time the peak of duels. Society was gripped by a real dueling fever,” and challenges were sometimes thrown for the most insignificant reasons.

The situation after the defeat of Napoleon I was fueled by the presence in France of significant occupying forces of Russians, Austrians, Prussians and British. All of them, together with the French - both royalists and Bonapartists - enthusiastically fencing and shooting, arguing about politics, art and women.

As for Nicholas I, his accession to the throne turned out to be connected with the sad events of the suppression of the Decembrist conspiracy, among whom there were many duelists. The new emperor considered duels barbaric, but they continued behind the scenes.

They were punished for a duel, they could be sent to serve in the Caucasus, where there was a constant war, or expelled from the country, like the foreigner Dantes, who shot Pushkin.

But usually the witnesses—representatives of noble society—gave mutually agreed upon testimony about the accident,” and the fight remained without consequences.

Pushkin in the Encyclopedia of Russian Life "-Eugene Onegin" left a poetic description of the duel:

The pistols are already flashing, the hammer is rattling on the ramrod. The bullets go into the faceted barrel, and the trigger clicks for the first time.

Throughout the mid-19th century, the humanization of morals led to a gradual decrease in the number of duels. Which declared themselves with renewed vigor after they were officially resolved in 1894 and proclaimed the most effective way to protect honor.

At the same time, the custom found many critics who accused the duelists of bloodthirstiness. The most striking reflection of this opinion was Kuprin’s story The Duel.” In it, the positive hero Lieutenant Romashov dies from a completely insignificant intrigue so that the senior careerist Nikolaev can enter the Academy of the General Staff without unnecessary rumors.

Interesting Facts

Few people know that Dantes, who was excommunicated from noble society after the duel with Pushkin, was ostracized not because of the murder of the famous poet, but because he violated the rules of a duel.

The fact is that after the descent began and Dantes shot, Pushkin, having been wounded, dropped the pistol, which failed when it fell into the snow. It is worth noting that the rules of the duel prohibited any of the fighters from changing weapons during the fight.

But Pushkin demanded that the pistol be replaced and Dantes allowed him to do so. After Alexander Sergeevich’s shot, Dantes fell, but the wound was slight.

The thing is that in a duel they usually took two pairs of pistols, and often the reserve pair was equipped with weakened charges, so that the issue could be resolved without bloodshed and without damage to reputation.

Some sources believe that the second pair of pistols in this duel had just such a charge.

Dantes agreed to replace the weapon, thereby putting himself in a more advantageous position. It is unknown whether he knew in advance about the presence of a weakened charge; most likely, he guessed, but, nevertheless, he authorized the use of such a weapon. For which he later paid.

One of the famous cases of a nobleman being challenged to a duel by a commoner is again associated with Dantes; he was subsequently challenged to a duel by a commoner, but Pushkin’s killer refused the challenge on legal grounds.

Cherchez la femme

The duels described above are united by one factor - a woman. In the Russian Empire, duels often occurred because of an insult to the honor of a woman or because of an insult to the honor of someone who considered her his.

Another well-known “romantic” duel can be considered the so-called duel of four, in which Griboedov also participated. We are talking not about one duel, but about two, which took place in 1817-1818 in St. Petersburg and Tiflis. In the first of them, cavalry guard Vasily Sheremetyev and Count Alexander Zavadovsky came together.

Sheremetyev challenged Zavadovsky to a duel after he met Sheremetyev’s lover, ballerina Avdotya Istomina, in his apartment. Griboyedov found himself involved in this story due to the fact that it was he who brought the beauty to the apartment of his friend, with whom he was then living.

According to the memoirs of playwright Zhandre, a contemporary of these events, Sheremetyev did not know who he should challenge to a duel, and asked his friend Yakubovich for advice. It was he who suggested to the jealous man that there were “two faces demanding a bullet.”

As a result, in November 1817, a duel took place between Sheremetyev and his offender Zavadovsky, the next day after which the wounded cavalry guard died. But his honor was still restored.

As Lotman wrote in his book “Conversations about Russian Culture

Life and traditions of the Russian nobility of the 18th – early 19th centuries,” the very fact of shedding blood (no matter whose) was already enough to restore the damage caused

Sometimes the fight took place bare-chested

It was believed that, firstly, women’s clothing restricts movement, and, secondly, a corset can protect too well from blade strikes, and it was much easier to hide armor under it. And thirdly, pieces of clothing could get into the wound, which would lead to infection. Of course, such a duel was carried out in a purely female society, even male servants had to move a decent distance away and wait, turning away, until they were called.

Sometimes it happened that a lady was forced to fight with a man. It is clear that no one would accept a challenge from a woman, for fear of being disgraced (regardless of the outcome), and then tricks and disguises were used.

In France lived Mademoiselle La Maupin (1673-1707), known for having killed several men in duels and loved to dance at royal balls dressed in men's clothing, and when they tried to kick her out, she threateningly drew her sword. And, although King Louis XIV prohibited duels, the monarch, greedy for feminine charms, turned a blind eye to her antics.

Also in the 17th century in France, a certain officer, taking advantage of the hospitality, arbitrarily occupied the room of the Countess of Saint-Belmont and behaved provocatively. After some time, he received a call from a certain “Chevalier de Saint-Belmont”. And what was the amazement of the brave captain when the lord not only disarmed him in a duel, but also turned to him with the words: “You think, monsieur, that you fought with the chevalier. You are mistaken, I am Madame de Saint-Belmont. And I earnestly ask you to be more sensitive to women’s requests in the future.”

The fashion for noble duels came to Russia from Europe, and they showed themselves especially clearly during the time of Catherine II, who in her youth herself fought a duel with her second cousin, so she turned a blind eye to the pranks of her subjects. During this era, Princess Ekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova also became famous, who in 1770, while staying in London, quarreled with a local aristocrat, immediately going to fight with her with swords in the garden. Having received minor wounds, the ladies parted in peace.

Later, in the 19th century, noblewomen organized their own closed dueling clubs, called “literary salons” for cover. So, in the salon of a certain Mrs. Vostroukhova, according to some sources, in 1823 seventeen women’s fights took place. Of course, the metropolitan fashion spread to the provinces, and so, in June 1829, landowners Olga Zavarova and Ekaterina Polesova fought with their husbands’ sabers, so zealously that both died. Their growing daughters took up their cause, and five years later Alexandra Zavarova killed Anna Polesova in the same duel, which she wrote down with satisfaction in her diary, which is how we know the details.

By the beginning of the 20th century, dueling fever had died down, turning into a farce. For example, because of the attention of the famous composer Liszt, the French writer George Sand fought on her nails with the composer's lover, Maria d'Agu, and their chosen one was sitting in the next room at that time and was waiting for the final battle of their furies.

Fortunately, in our time, girls do not so often use weapons to prove that they are right, although the Internet is replete with videos of the most brutal female fights, but here at least they only use fists and legs, so fatalities are rare. Fights with women show us that the art of war is not alien to beautiful ladies, and weapons in their hands greatly level the odds.

Duel of two kings

The right to judicial combat was invariably preserved and confirmed in medieval codes.

Duel between Edmund Ironside and Canute the Great

On the same topic

Canute the Great, Sven Forkbeard and the Danish-English Empire

It got to the point that in 1016, two kings fought in a duel - the English Edmund Ironside and the Danish Canute the Great. The reason for the duel was simple - Canute wanted to conquer Britain, and Edmund did his best to interfere with him in this difficult matter. Having met on the battlefield, the two rulers, after a short conversation, came to the conclusion that their people were tired of fighting.

So why not decide the fate of the crown with just one fight?

The duel of kings took place on horseback. Edmund, being stronger than Canute, broke his shield with a powerful blow and was already preparing to strike a fatal blow when the Dane stopped the fight, offering to divide the island in half instead of shedding blood. So they decided.

However, Edmund soon died, so England went to Canute. By the way, according to one version, Edmund was shot with a crossbow while sitting in a latrine. The plot was reproduced by J. Martin in Game of Thrones, where Lord Tywin Lannister died at the hands of his son Tyrion.