To leave a mark on history, you do not have to be a brilliant politician or a significant military leader. Sometimes it’s enough just to found a “lucky” dynasty, and your descendants themselves will glorify you for centuries, writing many fables and legends about you. This happened to the Viking leader Rolf the Pedestrian.

This glorious leader of the robbers of Europe was not nicknamed the Pedestrian for nothing - according to legend, he was so huge that they simply could not find a horse for him. He had to travel on foot. In addition, in France he was called Rollon or Rollo, and fate wanted him to become the first ruler of Normandy. However, he was never named Duke during his lifetime. Chroniclers wrote that he was a “principal,” that is, a ruler, a leader.

Norwegian, son of a jarl

Scandinavian sagas wrote about the Norwegian origin of Rolf the Pedestrian. Data from European chronicles contradicted this: they wrote that Rolf was a Dane who fled the country after the death of his father. The most famous literary work that glorified Rolf the Pedestrian was the Orkney Saga, and thanks to it, many modern historians are inclined to believe that Rolf was a real Viking from the north of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The exact date of his birth is unknown, his father was Jarl Mera Regnvald Øysteinsson, who ruled a small kingdom that was located between Trondheim and Bergen in western Norway. Around 860, the domain of Mer was captured by the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair. Apparently, Rolf the Pedestrian understood that he, as an unwanted heir to the former ruler, could easily be poisoned or stabbed to death. Therefore, he and his squad left the harsh shores of Norway and rushed to Europe, where in those years it was possible to get rich without much difficulty through robberies and extortions, raiding the territories of Britain, Scotland, Ireland and the coast of Western Europe.

Links[edit]

Quotes [edit]

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Rutledge. paragraph 83. ISBN 978-0-415-41395-4.

- Boué, Pierre (2016). Rollon: Le chef viking qui fonda la Normandie

(in French). Tallander. paragraph 76. - Hjardar, Kim; Wicke, Vegard (2016). Vikings at War

. Casemate Publishing and Book Distributors, LLC. item 329. ISBN. 979-1021017467. - Jump up

↑ Bates 1982, pp. 8–10. - Flodoard Reimse (2011). Fanning, Stephen; Bachrach, Bernard S. (ed.). Annals of Flodoard Rheims: 919-966

. University of Toronto Press. pp. XX – XXI, 14, 16–17. ISBN 978-1-44260-001-0. - "Rollo". Encyclopedia Britannica

. August 28, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2022. - Neveu, Francois; Curtis, Howard (2008). A Brief History of the Normans: The Conquests That Changed the Face of Europe

. Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84529-523-3. - Jump up

↑ Ferguson 2009, p. 180. - Jump up

↑ Crouch 2006. - Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas, ed. (2007). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. paragraph 77. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

- Weiss (2004). Burgess, Glyn S. (ed.). History of the Norman People: A Romance by de Roo Weis. Boydell Press. clause 11. ISBN 978-1-84383-007-8.

- Little, Charles Eugene (1900). Cyclopedia of Classified Dates: With a Comprehensive Index by Charles E. Little... for students of history and for all persons desiring quick access to facts and events relevant to the histories of various countries of the world. world from the earliest recorded dates. Funk & Wagnalls Company. paragraph 666. OCLC 367478758. rollo paris 885–886.

- "Viking Travellers: To the Gates of Paris". History.com

.

History Channel. September 4, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2020. [ unreliable source

] - Mark, Joshua J. (November 27, 2022). "Odo of Western France". Encyclopedia of World History

. - Dudo 1998, Chapter 5. Dudo uses the terminology of the time, Scandia for the southern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula and Dacia for Denmark (also the name of a Roman province near the Black Sea).

- Jump up

↑ Ferguson 2009, p. 177. - Malaterra, Jeffrey (2005). "The acts of Count Roger of Calabria and Sicily and Duke Robert Guiscard, his brother, Geoffery Malaterra". Translation by Loud, Graham A. p. 3.

- William Malmesbury (1989) [1854]. Stevenson, John (ed.). Kings before the Norman Conquest

. Volume II, 127. Translated by Sharp, John. Seeleys, London: Llanerch. p. 110. |volume=there is additional text (help) - Rollo and his followers are called Daneis throughout the Chronique

. For example, Iriez fu Rous en son curage […] Ne lui nuire n'à ses Daneis (Francis Michel edition, p. 173, available online at Internet Archive). - "4 - Shetland and Orkney Islands." The Orkneying Saga

. pp. 26–27. - Sturluson, Snorri (1966). King Harald's Saga: Harald Hardrady of Norway

. Translated by Magnusson, Magnus; Palsson, Hermann. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044183-3. - Jennings, Andrew; Kruse, Arne (2009). "From Dal Riata to Gall-Gaidheil" (PDF). Viking and medieval Scandinavia

.

5

: 129. DOI: 10.1484/J.VMS.1.100676. - ^ B Bull, Edward; Krogvig, Anders; Grahn, Gerhard, ed. (1929). Norsk biographical lexicon

(in Norwegian). Volume 4. Oslo: Aszehug. pp. 351–353. |volume=there is additional text (help) - ^ ab La Fay, Howard (1972). Vikings. Special publications. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. pp. 146, 147, 164–165. ISBN 978-0-87044-108-0.

- Wolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press. paragraph 296. ISBN 978-0-7486-2821-6.

- Van Houts 2000, p. 43.

- Jump up

↑ Dudo 1998, p. xiv. - Ferguson 2009, pp. 177-182.

- Jump up

↑ Dudo 1998, pp. 38–39. - "Robert I of France". Encyclopedia Britannica

. - Van Houts 2000, p. 25.

- Jump up

↑ Dudo 1998, pp. 46–47. - ^ a b Ferguson 2009, p. 187.

- Bauduin, Pierre (2005). “Norman chefs and elite francs, fin IX e –début X e siècle.” In Bauduin, Pierre (ed.). Les Fondations scandinaves en Occident et les débuts du Duché de Normandie

(in French). CRAHM. paragraph 182. - ^ a b Dudo 1998, p. 49.

- Jump up

↑ Bates 1982, pp. 20–21. - ^ abc Crouch 2006, p. 6.

- Jump up

↑ Crouch 2006, p. 8. - Jump up

↑ Ferguson 2009, p. 183. - Searle, Eleanor (1988). Predatory kinship and the creation of Norman power, 840–1066

. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-520-06276-4. - Brown, R. Allen (1984). Normans

. Boydell and Brewer. paragraph 19. ISBN 0312577761. - Jump up

↑ Dudo 1998, pp. 69–70, 201. - William of Jumièges; Orderic Vitalis; Robert Torigny (1992). Van Houts, Elizabeth M.S. (ed.). Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitali and Robert de Thorigny

. Volume 1. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-19-822271-2. |volume=there is additional text (help) - "Viking 'forefather of British Royals'". Views and news from Norway

. June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011. - "Was the Viking ruler Rollo Danish or Norwegian?" . Local

. March 2, 2016. Retrieved October 6 +2016. - "Skeletal shock for Norwegian explorers on Viking hunt". Norway today

. November 23, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2022. - ^ a b Van Houts 2000, p. 15.

- Turnbow, Tina (March 18, 2013). "Reflections of a Viking" by Clive Standen. HuffPost

. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

Sources [edit]

- Bates, David (1982). Normandy Before 1066

. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-48492-4. - Crouch, David (2006). The Normans: a history of a dynasty. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85285-595-6.

- Dudo of Saint-Quentin (1998). Christiansen, Erik (ed.). St. Quentin's Dudo:

A History of the Normans. Woodbridge. ISBN 978-0-85115-552-4. - Ferguson, Robert (2009). The Hammer and the Cross: A New History of the Vikings

. London: Allen Lane, an imprint of the Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-670-02079-9. - Van Houts, Elizabeth (2000). Normans in Europe

. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4751-0.

Siege of Paris

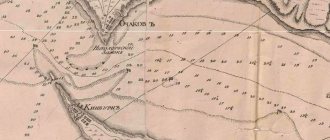

It is known that around 886, Rolf the Pedestrian, at the head of a large detachment, arrived on the territory of the West Frankish kingdom and took part in the famous siege of Paris. It was in France that he acquired his middle name - Rollon. Paris in those years was a fortress located on an island on the Seine River. The city suffered constantly from raids by northerners. Year after year the Vikings stormed and plundered it. Only in 881 did the Parisians manage to defeat the Vikings at the Battle of Socourt-en-Vime. But five years later, the northerners returned to the city with a huge army to once again fill their traveling bags with silver and gold. According to the chronicles of the Parisian Benedictine monk Abbon the Hunchback, the Vikings arrived on seven hundred ships and there were at least 40 thousand of them. This figure seems too high to modern historians. A number of other sources speak of 300 longships and, accordingly, 12-15 thousand warriors. The army of the northerners consisted of several squads. One of them was headed by Rolf Pedestrian, but there were other leaders, for example, a certain leader Siegfried negotiated with the Parisians. The Vikings besieged the city, which refused to pay them tribute, and, with the help of ballistas and catapults, attacked the tower that guarded the eastern bridge connecting Paris with the banks of the Seine. The Franks managed to repulse the attack, and then the Vikings began a long siege. The barbarians from the north resorted to a variety of tricks to enter the city: they tried to fill the arm of the Seine with garbage and corpses in order to bypass the security tower, then they tried to set fire to the bridge with the help of burning ships. In the end, the bridge collapsed under the pressure of water, and the Vikings managed to capture the tower, cut off from the city. Soon, many of the Vikings got tired of the siege, and they went to plunder the surrounding area. However, Rolf's soldiers remained under the walls of Paris and soon learned the sad news for them - an army of Franks led by the Marquis Henry came to the aid of the townspeople. To speed up the surrender of Paris, Rolf's Vikings resorted to cunning - they threw plague-infected corpses of people and animals over the city walls. An epidemic began in Paris. Rolf's Vikings managed to kill Marquis Henry by cunning and hold out near Paris for several more months. However, soon the army of King Charles III Tolstoy came to the city. He surrounded Rolf's squad. By this time, Siegfried had already received a ransom of 60 pounds of silver from the besieged Parisians and went home. Rolf managed to come to an agreement with Karl. The Franks freely allowed the Vikings into Burgundy, and Paris paid Rolf a tribute of 700 livres in silver. It is obvious that for several years Rolf walked unhindered along the Seine and robbed ships and settlements. In France, for this he was nicknamed “the leader of the pirates.”

Portrayals in fiction[edit]

Statue of Rollo in Falaise, France

Rollo is the subject of the 17th century play Rollo Duke of Normandy

, written by John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson and George Chapman.

The character, loosely inspired by the historical Rollo but including many events that happened before the real Rollo was born, played by Clive Standen, is the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok in the History Channel television series Vikings

. [48]

Rollo is a character in the video game Assassin's Creed: Valhalla that you can interact with, including several quests that end with him leaving England and settling in France.

Thin world

Of course, the campaigns of Rolf the Pedestrian could not but cause discontent among the Franks. And, in the end, in 911, the battle of Chartres took place between the Vikings and the army of King Charles III the Simple, where Rolf’s squad was completely defeated. The defeat, obviously, somewhat sobered up the Viking leader, and he went to make peace with the king. Charles III, in turn, was also interested in peace with Rolf, as he intended to establish his power in the east of France. A peace treaty was signed between Rolf and Charles III at Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. According to it, Rolf the Pedestrian, together with his entire retinue, pledged to accept Christianity and recognized the king as his lord, and Charles III gave him the city of Rouen (the territory of modern Upper Normandy) with the coast of the Seine River, as well as Brittany, Er and Caen as fiefs. Among other things, the king undertook to give his daughter Gisela as a wife to the Viking. It is known that Rolf was already married or cohabiting with the Christian Poppa de Bayeux and had three children from her - a son named William Longsword, who later became Duke of Normandy, daughter Gerlock, who married the Aquitaine Duke William III of Aquitaine, and daughter Cadlin, who was married to the Scottish king Bjolan. Of course, he did not refuse the offer to marry the king’s daughter, but, according to some reports, he treated the young woman so cruelly that Charles III was once even forced to send two soldiers to protect his daughter from her husband’s rudeness. Rolf-Rolland ordered their death, and Gisela died shortly after the marriage. In general, the king failed to reconcile the stern and hot-tempered Viking with Christianity and a legal wedding. It is known that at baptism Rolf was given another name - Robert. While swearing allegiance to King Charles III, Rolf flatly refused to kiss the monarch’s feet. And when the Franks began to insist, then, according to legend, instead of falling at the royal foot, he decided to bring it to his lips, and Charles III fell on his back, which caused laughter among the people. However, it is difficult to say how reliable this legend is.

Name [edit]

It is generally assumed that the name Rollo is a Latinization of the Old Norse name Hrólfr, a theory which is supported by the rendition of Hrólfr as Roluo

in

Gesta Danorum

.

It is also sometimes suggested that Rollo may be a Latinized version of another Scandinavian name, Hrollaugr

. [8]

The 10th-century French historian Doudo recorded that Rollo took the baptismal name Robert. [9] Variant spelling, Rou

, used in the 12th-century Norman French poetic chronicle

Roman de Roux

, compiled by Wace and commissioned by King Henry II of England, a descendant of Rollo. [10] [11]

Further reading[edit]

Basic texts [edit]

- Dudo of Saint Quentin (1998). Erik Christiansen (ed.). History of the Normans

. Translation by Erik Christiansen. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. - Elizabeth van Houts, ed. (1992). Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Order of Vitalis and Robert of Thorin

. - Elizabeth van Houts, ed. (2000). Normans in Europe

. Translated by Elizabeth van Houts. Manchester and New York: University of Manchester. - The Orkneying Saga: A History of the Earls of Orkney

. Translated by Palsson, Hermann; Edwards, Paul. London: Hogarth Press. 1978. ISBN 0-7012-0431-1.. Reprinted 1981, Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044383-5.