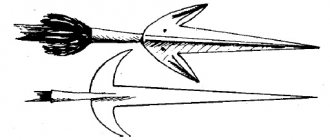

Kusarigama (kusarikama) is one of the varieties of Japanese traditional weapons, which includes: a sickle (kama or gama) and a chain (kusari), connected with a striking weight (fundo). The point at which the chain attaches to the sickle can vary from the edge of its handle to the base of the sickle blade.

The art of controlling kusarigama (kusarigama-jutsu) is part of traditional kobudo - the Japanese martial art of handling edged weapons. If you look at the drawing of a kusarigama, you can find a combination of several types of weapons in it at the same time: piercing-cutting, throwing, and impact-crushing.

Some believe that kusarigama is an invention of ninjas from the Middle Ages. First, the idea, and then the prototype for this invention, was the observation of an ordinary agricultural sickle, with the help of which Japanese peasants had to harvest crops. During raids, soldiers of that time also often had to cut a path for themselves through tall grasses and other bushes with sickles. Some experts believe that the appearance of kusarigama was caused by the necessary disguise of weapons as objects of agricultural labor that did not raise anyone's suspicions.

Types of kusarigama

Experts distinguish two types of kusarigama: farm and military. The first sickle designs had short blades that resembled curved bird beaks. The blade designs of the latter were more reminiscent of small swords. For both, the attachments to the handles were made of hardwood.

Farmer kusarigamas do not have the same throw range as military ones. In addition, they are not as effective in close combat. These types of combined weapons are bilateral.

Modern use[edit]

In Episode 9 of This Is Japan

from

the Asahi Shimbun

states: "Perhaps the most unusual Japanese martial art is that which uses

kusarigama

.

The fact that it has survived throughout history speaks volumes about its effectiveness. However, a casual observer not trained in its use would be inclined to regard it as a silly toy." [11] Tadashi Yamashita's book, which teaches people how to use the Okinawan kusarigama, was advertised in Black Belt

in the 1980s. [12] [13]

In the Republic of Ireland, the Kusarigama

classified as an illegal offensive weapon.

The Firearms and Offensive Weapons Act 1990 in Ireland does not permit the manufacture, import or sale of kusarigama

and other similar weapons. These actions can result in a prison sentence of up to seven years. [14]

Tactics for using kusarigama

Most Japanese warriors, especially samurai, considered the kusarigama to be an unfair weapon due to the presence of combined and versatile elements in it. Some experts believe that kusarigama was not so widespread due to the very long period of training in the art of fighting with it.

Combat tactics consisted of throwing sinkers at enemies or entangling them with a chain and then using a sickle. There was another method of application, in which throwing was carried out directly with a sickle, returning with the help of a chain.

Use of weapons

Using the kusarigama control technique allowed:

- strike the enemy with a fundo weight;

- entangle with a chain;

- then attack with the sickle.

They also carried out throwing actions with the sickle itself and returned it using a chain. It was often necessary to use kusarigama in the defense of fortresses. Learning to use it is a rather long and complex process, but the good combat versatility of the weapon compensates for the time spent. They can be applied:

- Cutting.

- Stabbing.

- Crushing.

- Throwing actions.

There are even arts for fighting using this device:

- kusarigamajutsu;

- kobudo;

- kukishinden-ryu;

- happo-hiken-ju.

For example, Kobudo is a traditional Okinawan martial art of bladed weapons. In the Kuki family of small feudal lords, the knowledge of Kukishinden-ryu and Happo-hiken-ju battles was passed down from generation to generation. The school's technique belongs to the samurai style of Katori Shinto-ryu, Kashima Shinto-ryu.

The martial art of Kukishinden-ryu is considered unrelated to ninjas, since the fighting technique uses heavy samurai armor - eroi.

There was a period in Japan when provinces fought with each other and then warriors used more sophisticated loads for kusarigama. For example, stilettos in the form of snakes were used with mamushigama weapons, and sometimes live reptiles were attached to the device; they attacked the enemy with their poison.

There were many variations of this weapon, ranging from small in size to impressive.

They are easy to disassemble and transport, so each owner created their own models. So, devices were attached to the knob that:

- Exploded.

- They were burning.

- Or blinded.

There were also very large models - these are o-gama, and in kaen-kusarigama the load was wrapped in cloth, which was then set on fire or replaced with a small torch.

Varieties of kusarigama

Japanese fighters came up with a huge number of varieties of kusarigama. So, in some variations the fundo was replaced with rather specific attributes:

- Skeins of burning fabrics;

- Explosives in special containers;

- Live poisonous snakes;

- Torches and stuff.

When, instead of traditional weights, kusarigamas were equipped with bags of explosive mixtures, this type of weapon was called “bakuhatsu-gama,” which translated as “explosive sickle.” The most important highlight of this ingenious device was complete surprise for the enemy upon direct contact with him, and especially from the impact of the original “explosive package”.

As a result of the weapon's contact with the enemy, a thunderous explosion was heard, which completely led to the enemy's disorientation for some time. After such contact, the enemy faced the attacker in a more vulnerable position for subsequent attacks. This type of kusarigam was especially effective against a group of enemies.

The types of kusarigama changed depending on which schools were involved in their development and combat use. Experts call the Isshin-ryu school one of the most successful schools in the field of kusarigama-jutsu. Some of them suggest that it was formed by Nen Ami Jiong in the 14th or 15th centuries, while others believe that Tang Issin, but later.

Actually, the kusarigama of this school differ among others in their design. They consisted of extremely long chains and straight blades, sharpened on both sides. And this despite the fact that, as a rule, they were sharpened only from the inner parts of the sickles. In addition, the kusarigama of the Isshin-ryu school had metal guards to protect their hands.

There was also the so-called kaen-kusarigama. Its distinctive feature from standard samples of similar weapons was that its sinker was wrapped in a piece of flaming material. As a result of this improvement, attackers achieved an incredible demoralizing effect on their enemies.

The most sophisticated and amazing component of this weapon was the use of a live poisonous snake. Mamushi were mainly used for these purposes. This is a type of Japanese cottonmouth. With the help of mamushi-gam, or snake sickles, the enemy was distracted. This provided the attackers with precious fractions of a second to deliver precise blows decisive for the outcome of the battle.

It is interesting that the warriors themselves accepted universal condemnation of these bladed weapons as not entirely honest.

The ninjas didn't die - they transformed

With the passing of the Sengoku era, when stability came to the country and civil strife ended, the need for ninjas almost disappeared. Professional killers and spies were part of the feudal world and, with its decline, were no longer so in demand. However, the shinobi did not disappear overnight: the government figured out how to win them over to its side and at the same time deprive them of their clan independence.

A descendant of Tokugawa Ieyasu, shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune, founded the secret service Oniwaban (“Guardians of the Garden”, “Gardeners”), accepting loyal shinobi into it. This was internal intelligence, the purpose of which was to collect information about daimyo princes and government officials. The employees of this special service were directly controlled by the shogun and were his eyes and ears. That is, the experience accumulated by the shinobi clans was not lost, it simply turned in the direction desired by the government.

The last time ninjas were actively used as military spies was during the Shimabara Christian Uprising in 1638. Shinobi from the Koga clan helped government troops take the Hara citadel: they destroyed the besieged's supplies, drew up a detailed plan for the fortress, and were even able to steal the standard of the Christians, undermining their morale.

Left without government support, the ninja were forced to adapt to new conditions. Feudalism was losing ground, giving way to bourgeois relations, but ninja skills had a place here too. From mercenaries of daimyos and shoguns, they became mercenaries of merchants and manufacturers. Industrial espionage, sabotage at competitors' factories and warehouses - the new order created new ninjas. And in this world there would no longer be a place for the hero of Sekiro.

- Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice will be released on March 22 on PC, PS4 and Xbox One. Our preview of the game can be seen here.

- Official game page.

What was achieved with the help of kusarigama

Well-trained warriors, if they had competent handling of kusarigama, were allowed to combine close and ranged combat techniques. Defending against such unpredictable bidirectional weapons has proven to be a difficult task in practice. Warriors who mastered the kusarigama could successfully fight the most serious opponents.

Using the enemy's sinker:

- Disarmed;

- Stunned;

- Injured;

- Disoriented;

- Immobilized, etc.

They repelled blows with sickles and also finished off the enemy. Sometimes the sickle was thrown and then returned using a chain. The main disadvantage of this weapon was the need for a large open space for the heavy chain to swing freely.

Links[edit]

- ^ B s d e g ,

2014).

Old School: Essays on Japanese Martial Traditions

. Freelance Academy Press. pp. 118–122. ISBN 978-1-937439-47-7. - Carl F. Friday; Seki Humitake (July 1, 1997). Legacy of the Sword: Kashima-Shinryu and the Martial Culture of the Samurai

. University of Hawaii Press. paragraph 122. ISBN 978-0-8248-6332-6. - Oscar Ratti; Adele Westbrook (December 20, 2011). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan

. Tuttle Publishing. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-4629-0254-5. - Donn F. Draeger; Robert W. Smith (1980). Integrated Asian martial art

. Kodansha International. paragraph 127. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6. - Hosey, Timothy (December 1980). "Masters of the Broom and Sword". Black belt

. Vol. 18 no. 10. pp. 45–8. - Serge Mol (2003). Classic Weapons of Japan: Special Weapons and Martial Arts Tactics

. Kodansha International. item 146. ISBN. 978-4-7700-2941-6. - Active Interest Media, Inc. (May 1992). Black belt

. Active Interest Media, Inc. page 30. - Don Cunningham (August 21, 2012). Samurai Weapons: The Warrior's Tools

. Tuttle Publishing. paragraph 31. ISBN 978-1-4629-0749-6. - Donn F. Draeger; Robert W. Smith (1980). Integrated Asian martial art

. Kodansha International. paragraph 67. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6. - Oscar Ratti; Westbrook, A. (1991). Secrets of the Samurai; A Survey of the Martial Arts of Feudal Japan

. C. E. Tuttle. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7. - This is Japan

. Newspaper publishing house Asahi Shimbun. 1962. p. 212. - Active Interest Media, Inc. (March 1987). Black belt

. Active Interest Media, Inc. page 75. - Active Interest Media, Inc. (September 1986). Black belt

. Active Interest Media, Inc. page 108. - "FAQ" . Dublin Department of Justice

. Retrieved December 29, 2022.