Straight, double-edged bladed weapon

Sword

| Knight's sword | |

| A copy of the Sword of Saint Maurice, one of the best preserved swords of the 13th century, now kept in Turin. It has a heavy Type XII blade, presumably intended for use on horseback, with a Type A "Brazil nut" pommel. (Reply by Peter Johnsson, 2005) [1] | |

| Type | Sword |

| Service history | |

| In service | c. 1000–1500 |

| Characteristics | |

| Weight | avg. 1.1 kg (2.4 lb) |

| Length | avg. 90 cm (35 inches) |

| Blade length | avg. 75 cm (30 inches) |

| Blade type | Double sided, straight blade |

| Handle type | One-handed cross-shaped, with pommel |

In the European Middle Ages, a typical sword

(sometimes academically classified as

a knight's sword

,

war sword

, or full

knight's war sword

) was a straight, double-edged weapon with a one-handed cruciform (i.e., cruciform) weapon. shaped) handle and blade length from 70 to 80 centimeters (28 to 31 in). The type is often depicted in contemporary art, and numerous examples have survived archaeologically.

The tall medieval sword of the Romanesque period (10th-13th centuries) gradually developed from the Viking sword of the 9th century. During the late Middle Ages (14th and 15th centuries), later forms of these swords continued to be used, but often as sidearms, at that point called "arming swords" and contrasted with the two-handed, heavier bastard swords.

Although most late medieval weapon swords retained the blade properties of previous centuries, there are also surviving examples from the 15th century that took the form of the late medieval estoc, specialized for use against more heavily armored opponents. After the end of the medieval period, the fighting sword evolved into several forms of early modern one-handed straight swords, such as the side sword, rapier, cavalry Reiterschwert

and some types of broadswords.

Terminology[edit]

The term "fighting sword" ( espées d'armes

) was first used in the 15th century to refer to a one-handed type of sword after it ceased to serve as a primary weapon and began to be used as a weapon. side sword. [2] "Arm sword" in late medieval usage specifically refers to an estok when carried as a weapon, [3] but as a modern term it can also refer to any one-handed sword in a late medieval context. The terms "knight's sword" or "knight's sword" are modern retronyms for a sword from the High Middle Ages.

Period terminology for swords is somewhat fluid. In most cases, the common type of sword in any given period will simply be called a "sword" (English swerde

, French

espée

, Latin

gladius

, etc.).

During the High Middle Ages, references to swords as "great sword" ( grete swerd

,

grant espée

), "small sword" or "short sword" (

espée courte

,

parvus ensis

) do not necessarily indicate their morphology, but simply their relative size. Oakeshott (1964) notes that this changes in the late Middle Ages, beginning in the late 13th century, when the "bastard sword" appeared as an early example of what would become the 15th century longsword.[4]

The term "Romanesque sword" does not find significant use in English, but it is more relevant

in French (

epée romane

), German (

romanisches Schwert

) and especially in Slavic languages (e.g. Czech

románský meč

, etc.),

where

swords are identified by being contemporary with the corresponding Romanesque period in art history (roughly 1000 to 1300).

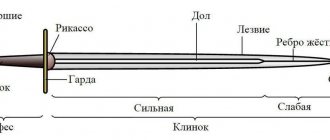

One-handed sword counters plate armor

Replica one-handed sword

Simple chain mail began to be reinforced with metal plates at the end of the 18th century. This is how lamellar types of protective clothing appeared. These developments also modified the shape of the blade of swords. The sword could no longer cut through the plates in the defense; now the emphasis was on point-impact weapons. The blade of the sword became narrower, and a clearly defined sharp tip appeared. Now the cross-section of the blade during the manufacture of weapons was made more diamond-shaped, and an additional stiffening rib appeared. After all, the main load of the blades went to the edge. The weapon acquired a more piercing blade.

Now a completely different group of swords appeared. Here, weapons vary greatly in blade type. Even though the time has come for a longer blade on the sword, one-handed swords have their place. What makes these swords stand out: the guards are curved towards the blade, the handle is lengthened, the swords have a blade that is wide at the base and tapering towards the tip. The guard protects the fighter's hand from damage. The weapon had an average blade weight of about 1 kg. The blade length of such swords was usually about 75 cm, the hilt was about 10 cm.

History[edit]

Further information: Medieval sword, Norman sword, Estki, Longsword, Schiavona, and Spada da Lato

The knight's sword originated in the 11th century from the Viking Age sword. The most obvious morphological development is the appearance of the crossbar. 11th century transition swords are also known as Norman swords. As early as the 10th century, some of Ulfberth's "best and most elegant" "Viking" (actually Carolingian/Frankish) swords began to exhibit slimmer blade geometry, moving the center of mass closer to the hilt for improved handling. [5]

The one-handed sword of the High Middle Ages was usually used with a shield or buckler. During the late Middle Ages, when the long sword prevailed, the one-handed sword was retained as a common side cock, especially in the estoc type, and came to be called the "cocking sword", and then developed into the cut and thrust swords of this Renaissance.

- Great Seal of Henry II of England, showing the king as an armed horseman, c. 1154.

- So-called Guido relief

in Grossmünster, Zurich, depicts two fighters with helmets and teardrop shields, one with a dagger, the other with a sword (inscription

GVIDO

on the blade), c. 1160–1180. - Detail of a sword being drawn from its scabbard Morgan Bible

fol. 28v, 1250.

- Soldiers in chain mail armor with swords, German miniature " Massacre of the innocents"

, OK. 1250.

- Painting of a fighter with sword, helmet and teardrop shield, fresco in Gotham Church, c. 1300.

- Illustration of a mock tournament fight, Codex Manesse ( Herzog von Anhalt

, fol. 17r), c. 1305–1315.

- Illustration of combat with sword and buckler, Codex Manesse ( Von Scharpfenberg

, fol. 204r), c. 1305–1315.

- Fol. 4v Royal Armories MS I.33, sword and buckler combat manual, c. 1300.

- Judicial combat with sword and shield, depicted in the Dresden Mass. V Saxon mirror

, 14th century.

- Hand-to-hand combat between knights on horseback (Emperor Henry VII's troops defeating the Guelph revolt led by Guido della Torre in Milan, 1311), Codex Balduini Trevirensis

, OK. 1320–1340.

- Horse sword fighting at the Battle of Crécy (1346), Grandes Chroniques de France

fol. 152v, g. 1415.

- Painting by Condottiere Pippo Spano Andrea del Castagno, c. 1450.

At the end of the Middle Ages, the estoc combat sword became the Spanish espada ropera

and the Italian

spada da lato

, the predecessors of the early modern rapier. In a separate development, the schiavona was a heavier one-handed sword that was used by the Dalmatian bodyguard of the Doge of Venice in the 16th century. This type influenced the development of the early modern basket-hilt sword, which in turn evolved into the modern (Napoleonic period) cavalry sword.

Morphology [edit]

Main article: Oakeshott's typology

The most common typology of the medieval sword was developed by Ewart Oakeshott in 1960, based largely on blade morphology. Oakeshott (1964) introduced a further typology of pommel shapes.

A more recent typology is due to Geibig (1991). Geibig's typology focuses on swords from the continental transition period from the Early to High Middle Ages (early 8th to late 12th centuries) and does not extend to the late medieval period.

Blade length typically ranged from 69 to 81 centimeters (27 to 32 inches); however, examples from 58 to 100 centimeters (23 to 39 in) exist. [6] Most often, the “Brazil nut” pommel dates back to 1000–1200. AD [7], the "wheel" pommel appeared in the 11th and prevailed in the 13th to 15th centuries.

However, Oakeshott (1991) emphasizes that a medieval sword cannot be definitively dated based on its morphology. Although there are some general trends in fashion, many of the most popular pommel, hilt and blade styles remained in use throughout the Middle Ages. [8]

Blade[edit]

Common "knight's swords" of the High Middle Ages (11th - early 12th centuries) fall under types X to XII.

Type X is a Norman sword developed from the early medieval Viking sword by the 11th century. Type XI shows a development towards the more tapering point seen in the 12th century. Type XII is a further development typical of the Crusades period, with a sharpened blade with a shortened down. Subtype XIIa includes the longer and more massive "great swords" which were developed in the mid-13th century and were probably intended to counter improvements in mail armour; these are the predecessors of the late medieval bastard sword (see also Cawood sword).

Type XIII is a knight's sword, typical of the late 13th century. Swords of this type have long and wide blades with parallel edges, ending in a rounded or spatulate tip, and with a lenticular cross-section. The handles have become slightly longer, about 15 cm, which allows them to be used with two hands from time to time. The heads are mostly Brazil nut or disc shaped. Subtype XIIIa has longer blades and hilts. These are knightly “great swords”, or Grans espées d'Allemagne,

which in the 14th century gradually developed into a bastard sword. Subtype XIIIb describes smaller one-handed swords of a similar shape. The form classified as Type XIV develops towards the very end of the High Middle Ages, around 1270, and remained popular in the early decades of the 14th century. They are often depicted on the tombs of English knights of the period, but there are few surviving examples. [9] The continued use of the knight's sword as the "arming sword" of the late Middle Ages corresponds to Oakeshott's Types XV, XVI and XVIII.

- A copy of a Norman Type X sword, typical of the mid-11th - 12th centuries.

- Replica of a Type XI sword with a pommel of the "cocked hat" type (Type D), typical of the early 13th century.

- Copy of the "Sword of Saint Maurice" kept in Turin, a sword of type XII with a pommel of "Brazil nut" (type A)

- A copy of the sword "Tritonia" (kept in the Museum of Medieval Stockholm, Sweden, dated around 1300), a type XIIIb sword with a rare type of spherical pommel (type R).

- Replica of a Type XIV sword with a wheel pommel (type J), typical of the period 1270–1340.

- a copy of a sword of the XV type, typical of the early - mid-15th century.

- replica of a sword of type XVI (pommel type K) from the early-mid 14th century.

- copy of an XVIII type sword (type V pommel), typical of the late 15th century

Pommel [edit]

Oakeshott's finial typology groups medieval finial forms into 24 categories (some with subtypes). Type A is a "Brazil nut" shape inherited from the classic "Viking sword". Type B includes the more rounded A shapes, including the "mushroom" or "tea" shape. Type C is the "cocked hat" shape also found in Viking swords, with variants C. derived from D, E and F.

Type G is a disc pommel very common on medieval swords. Type H is a variant of the disc top with beveled edges. This is one of the most common forms throughout the 10th-15th centuries. I, J and K are derived variants of the discus bow.

Types L to S are rare forms and in many cases difficult to date. Type L has a trefoil shape; perhaps it is limited to 12th-13th century Spain. Type M is a special derived variant of the Viking Age multi-lobed pommel, found only in a very limited number of swords (see Cawood sword). Types P ("shield-shaped") and Q ("flower-shaped") are not known to be even attested on any surviving swords and are known only from ancient works of art. R - spherical pommel, known only from single specimens.

Types T to Z are pommel shapes used during the late Middle Ages; T is a form of 'fig', 'pear' or 'flavouring', first used in the early 14th century, but not commonly found until after 1360, with numerous derived forms until the 16th century. U - "key" type, used only in the second half of the 15th century. V - fishtail pommel, used in the 15th century. Z is a "cat's head" shape, apparently used exclusively in Venice. [10]

TO CHOK OR STAB - THAT IS THE QUESTION...

The history of European swords goes back to Antiquity and is directly related to the weapon traditions of the neighbors of Ancient Rome. Initially, the Romans fought with short gladiuses, but the Gauls and some Germanic tribes invented and adopted the spatu - a long chopping iron sword. Usually it was the Romans who extended their achievements to the barbarian environment, but here the opposite happened. Having accepted auxillary warriors - people from Celtic and Germanic tribes - into its ranks, the army of the great empire also borrowed a long sword, which soon became a common weapon for cavalry and heavy infantry. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire led to a general technological decline in Western Europe, which also affected military affairs. However, due to its relevance and significant role in the division of the post-Roman world, the sword practically did not degrade. The production technologies created by the empire and the high-quality iron deposits it developed, for example in the Ruhr basin or Roman Norica (now Austria), did not leave medieval Europe without high-quality blades.

The further development of the sword until its disappearance and transformation into other types of weapons was associated with the main stages of European history, with economic and social processes in medieval society, the formation of military classes, changes in battle tactics and, very importantly, the development of armor. The latter is generally characteristic of the entire history of weapons, which is nothing more than a dispute between a projectile, a means of attack, and means of defense.

Inscriptions on blades[edit]

Many European sword blades from the High Middle Ages have inscriptions on the blades. Inscribed blades were especially popular in the 12th century. Many of these inscriptions are distorted strings of letters, often clearly inspired by religious formulas, especially the phrase in nomine domini

and the word

benedictus

or

benedicat

.

The 12th-century fashion for blade inscriptions was based on an earlier tradition dating from the 9th to 11th centuries of the so-called Ulfbert swords. One chance find from East Germany, dating from the late 11th or perhaps early 12th century, combines Ulfberht

and

in nomine domini

(in this case

+ IINIOMINEDMN

). [eleven]

Many lobe inscriptions of the later 12th and 13th centuries are even more distorted, bearing no resemblance to the Nomine Domini

phrases sometimes resembling random strings of letters, such as

ERTISSDXCNERTISSDX

, [12]

+ NDXOXCHWDRGHDXORVI +

, [13]

+ IHININIhVILPIDHINIhVILPN +

(Pernik sword). [14]

A typology of sword blade inscriptions from the 8th to 13th centuries was presented by Geibig (1991).

Notes[edit]

- ↑

Previously kept in the Treasury of the Abbey of Saint-Maurice in Valais, where it had been preserved in a leather case since at least the 15th century, it was transferred to the Royal Chapel in Turin in 1591, along with the saint's relics, by order of Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy. Saint Maurice of Turin (albion-swords.com) - Oakeshott (1997: 44).

- George Cameron Stone, Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armour

, 2013, p. 18. - “The size of a sword has not yet determined its type, but here, and in the swords of the 14th and 15th centuries, it will be so. The reason here is partly because the XIIIa weapons are very large, partly because in their time they were different from their smaller contemporaries ter 'espées de Guerre' or 'Grete Swerdes'. […] Two-handed weapons in the 13th-15th centuries were not a specialized form of weapon; it was just an oversized specimen." (Oakeshott 1964, p. 42)

- Jump up

↑ Peirce (1990: 144). - Oakeshott, Ewart (1960). Records of the Medieval Sword

. - Loades, Mike (2010). Swords and swordsmen

. UK: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84884-133-8. - “I must reiterate my firm belief that you cannot date

a sword by its

type

, since most types - not all, as you will see - can span the entire medieval period. You also can't use cross shapes and pommel to date a sword - almost never. There are several, mostly used in the 15th century, that date back several decades and can be identified with the region; but most pommel types and cross styles cover the entire period; furthermore, within these types and styles there must be an infinite number of variations—personal, regional, and in some cases simply carelessness on the part of the carver who created them.” Oakeshott (1991: 64). - Chad Arnow, Spotlight: Oakeshott Type XIV Swords (myarmory.com, 2004).

- See Myarmoury.com for an online summary of Oakeshott's finial typology.

- Herrman, J. and Donat P. (eds.), Corpus Archäologischer Quellen zur Frühgeschichte Auf Dem Gebiet der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (7-12. Jahrhundert), Akademie-Verlag, Berlin (1985), p. 376.

- ↑

T. Wagner et al., “Medieval Christian inscriptions on sword blades,”

Waffen- und Kostümkunde

51 (1), 2009, 11–52 (p. 24). - "Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Heritage", British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog

, 3 August 2015 - Pernik sword, Friedrich E. Grünzweig: "Ein Schwert mit Inschrift aus Pernik (Bulgarien)", Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistics

61 (2006).

How were Russian swords different from knightly swords?

Nothing. The Romanesque sword with which Russian warriors fought was no different from the European one. The same blade, with a short fuller, the same long graceful crosshair and, most often, the same disc-shaped pommel.

As a rule, the Russian sword and the European sword were produced in the same workshops located in Western Europe. That is, the arms trade was established on a grand scale. The hallmarks of Frankish masters speak of this more than eloquently.

However, it was noted that there were also national preferences - among the “novels” found in Rus', swords with straight rather than with curved crosshairs are more common.

The most ancient Romanesque swords in Rus' are considered to be two swords from the Novgorod land. They were found in the burials of the Finno-Ugric people Vod, who lived in the territory that became a bone of contention between European knights and Novgorod.