Bronze Age swords appeared around the 17th century BC, in the Black Sea and Aegean Sea regions. The design of these types of swords was an improvement of a shorter type of weapon - a dagger. Swords replaced daggers during the Iron Age (early 1st millennium BC).

From an early time, the length of a sword blade could already reach more than 100 cm. The technology for making blades of this length was presumably developed in the Aegean Sea. Alloys used in production were copper and tin or arsenic. The earliest specimens over 100 cm were made around 1700 BC. e. Typical Bronze Age swords ranged from 60 to 80 cm in length, while weapons significantly shorter than 60 cm also continued to be made, but were identified differently. Sometimes like short swords, sometimes like daggers. Until about 1400 BC. the distribution of swords is mainly limited to the Aegean Sea and southeastern Europe. This type of weapon became more widespread in the last centuries of the 2nd millennium BC, in regions such as Central Europe, Great Britain, the Middle East, Central Asia, Northern India and China.

History of appearance

As stated earlier, Bronze Age swords appeared in the 17th century BC. e., however, they managed to completely displace daggers as the main type of weapon only in the 1st century BC. e. From the earliest times of sword production, their length could reach more than 100 cm. The technology for producing swords of this length was presumably developed in what is now Greece.

Several alloys were used to make swords, most commonly tin, copper and arsenic. The very first specimens, which were more than 100 cm long, were made around the 1700s BC. e. Standard Bronze Age swords reached 60-80 cm in length, while weapons that were shorter were also produced, but they had different names. So, for example, it was called a dagger or short sword.

Around 1400 BC. e. the prevalence of long swords was mainly characteristic of the Aegean Sea and part of the southeast of modern Europe. This type of weapon began to become widespread in the 2nd century BC. e. in regions such as Central Asia, China, India, Middle East, UK and Central Europe.

Before bronze began to be used as the main material for making weapons, obsidian or flint stone was used exclusively. However, weapons made of stone had a significant drawback - fragility. When copper, and later bronze, began to be used in the manufacture of weapons, this made it possible to create not only knives and daggers, as before, but also swords.

Bronze swords in battles and museums

Replica Bronze Age type G2 sword made by Neil Burridge for Eric Lu

...there were a warlike people, men who carried shield and sword... 1 Chronicles 5:18

Mysteries of history.

They say that they meet at every step. And that is why so many speculations have arisen around them. We know where, well, let’s say, this or that product began - it’s metal or stone... We know how its “fate” ended - it was made, it’s in our hands, it was found and we can hold on to it. That is, we know points A and B. But we do not know point C - how exactly this product was made and used. True, this was, in general, quite recently.

Today, the development of science and technology has reached the point where it is possible to conduct the most amazing research that gives amazing results. For example, the study of microcracks on the spear tips of Stone Age people made it possible to establish an amazing thing: at first they did not throw spears, but hit them, apparently approaching the victim closely or chasing him at a run. And only then did people learn to throw spears. It also turned out that the Neanderthals hit spears, but the Cro-Magnons already threw them, that is, they could hit the enemy from a distance.

The oldest bronze rapier sword of the early Bronze Age. Archaeological Museum of Poros, Tomb No. 3, Greece

It is clear that it would be simply impossible to discover this by any amount of speculation! Well, after the Stone Age came the age of metals, and new types of research again helped to learn a lot about it. Well, for example, the first bronze to appear was not tin, but arsenic, and this is surprising, because smelting such metal was a very harmful activity. So replacing harmful arsenic with harmless tin is by no means a whim of our ancestors, but a necessity. Other studies have been carried out on weapons made from bronze. The fact is that it has long been found out that for some reason all edged weapons began with the sword - a piercing weapon, not a chopping weapon, and even attached in a special way to a wooden handle! That is, the blades of the ancient, earliest swords did not have a handle. And it’s one thing to have a knife attached to the handle with three transverse rivets. But a metal knife can still do without the handle that goes into the handle, because it is short.

A typical Early Bronze Age dagger blade from Wessex, 164 mm long, with a wide "heel" for rivets

Classification of Bronze Age swords by Sandars. It clearly shows that the most ancient swords were exclusively piercing! Then swords with V-shaped crosshairs and a high edge on the blade appeared. The handle began to be cast together with the blade. For 1250 BC They were characterized by piercing-cutting swords with an H-shaped handle. It was integral with the blade, and wooden or bone “cheeks” were attached to it with rivets

But what about the ancient rapier swords, which were long? On “VO” such ancient swords from the Bronze Age have already been talked about. But since new data related to the study of these weapons has appeared today, it makes sense to revisit this interesting topic. Let's start with the fact that it is not clear where and it is completely unclear why and why some ancient blacksmith suddenly took and made using this technology not a knife, but a sword, moreover, with a blade more than 70 cm long, and even diamond-shaped. In which region of the planet did this happen and, most importantly, what was the reason for it? After all, it is well known that the same ancient Egyptians fought with spears, maces with stone heads, axes, but they did not have swords, although they used daggers. The Assyrians had long rapier swords, which we know from images on bas-reliefs. Europeans also knew such swords - long, piercing, and they were used by the ancient Irish, and the Cretans, and the Mycenaeans, and somewhere between 1500 and 1100. BC. they had a very wide range of use! In Ireland, in particular, a lot of them were found, and they are now kept in many British museums and private collections. One such bronze sword was found right in the Thames, and similar ones were found in Denmark and all in Crete! And they all had the same fastening of the blade to the handle using rivets. They are also characterized by the presence of numerous stiffening ribs or ridges on the blades.

That is, if we talk about the heroes of the Trojan War, we should keep in mind that they fought with swords approximately one meter long and 2-4 cm wide, and their blades were exclusively piercing. But what methods of armed struggle could lead to the appearance of swords of such an unusual shape is not clear. After all, purely intuitively, chopping is much easier than stabbing. True, there may be an explanation that the reason for the injection technique was precisely these same rivets. They withstood piercing blows well, since the emphasis of the blade on the handle fell not only on them, but also on the shank of the blade itself. But instinct is instinct. In battle, he suggests that cutting the enemy, that is, striking him in a segment of a circle, the center of which is his own shoulder, is much simpler and more convenient. That is, in general, anyone can swing a sword, just like swing an ax. It is more difficult to stab with a rapier or sword - you have to learn it. However, there are notches on the Mycenaean swords, which indicate that they were used for cutting blows, and not just stabbing! Although this was impossible to do, because with a strong side impact, the rivets easily tore the relatively thin layer of bronze in the blade's shank, causing it to break off from the handle, becoming unusable and suitable only for melting down!

Rapier sword with hilt and crosshair. Artwork by Neil Burridge

The ancient warriors, of course, were not at all happy with this, so soon piercing swords with a blade and a thin tang appeared, which were already cast as one. The tang was lined with plates of bone, wood and even gold to create a handle convenient for holding the sword! With such swords it was possible not only to stab, but also to chop, without fear of damaging the handle, and in the Late Bronze Age, according to the famous British weapons historian Evart Oakeshott, they were somewhere around 1100-900. BC. spread throughout Europe.

Replica of the so-called sword from Mindelheim of the Bronze Age (Halstatt sword, 900-500 BC) Length 82.5 cm. Weight 1000 g. The blade was made by the English blacksmith and foundry Neil Burridge. The grips and pommel are made by Kirk Spencer. View from the side of the handle

View from the blade

But then “something” happened again, and the shape of the swords once again changed in the most radical way. From a spiky rapier, they turned into a leaf-shaped, piercing-cutting sword similar to a gladiolus leaf, the blade of which ended with a tang for attaching the hilt. It was convenient to stab with such a sword, but the blow with its blade expanding towards the tip became more effective. Externally, swords became simpler; they were no longer decorated, which was typical of an earlier period.

Well, now let's think a little. Reflecting, we come to very interesting conclusions. It is obvious that the first swords in Europe were piercing swords, as evidenced by the finds of Mycenaean, Danish and Irish samples. That is, swords that required fencing with them, and therefore learning fencing techniques. Then fencing gradually began to give way to chopping as a more natural method of combat that did not require special training. The result was rapier swords with metal hilts. Then fencing completely went out of fashion, and all swords became purely chopping. Moreover, the swords found in Scandinavia do not show signs of wear, and bronze shields made of very thin metal cannot serve as protection in battle. Maybe “eternal peace” reigned there, and all these “weapons” were ceremonial?

Original bone pommel from Mindelheim

And the lower we go on the time scale, the more professional warriors we find, although, logically speaking (which is what many “interested in history” like to do!), it should be just the opposite. It turns out that the most ancient warriors used complex fencing techniques, using relatively fragile rapiers, but the later ones cut with swords from the shoulder. We know that Mycenaean warriors fought in solid metal armor made of bronze and copper, and even with shields in their hands, so it was impossible to hit them with a slashing blow. But you could try to inject someone into some joint or face. After all, the same helmets made of durable boar tusks did not cover the faces of the warriors.

Attaching the lining to the handle...

Rivets for fastening linings

Relief surface of the blade

All of the above allows us to conclude that the appearance of piercing and chopping swords did not mean a regression in military affairs, but indicated that it had become widespread. But, on the other hand, the presence of a caste of professional warriors among the ancient Irish, as well as among the Mycenaeans and Cretans, cannot but cause surprise. It turns out that the warrior caste of European peoples arose before every man of his tribe became a warrior and... received a piercing-cutting sword! And it may very well be that this was due precisely to the great rarity of bronze weapons. That such a deadly but brittle sword could not be given to everyone and that this situation only changed over time.

Finished handle with wooden pommel by Kirk Spencer

This is what a bronze blade looks like

And this is his tip!

Sword in hand!

No less interesting is the study of traces left by ancient weapons, as well as the assessment of their effectiveness. A very modern science such as experimental archeology deals with this. Moreover, it is not only amateur subverters of “official history” who are engaged in it, but also historians themselves.

Neil Burridge with a sword - a museum replica

At one time, VO published a number of articles in which the name of the English blacksmith and foundry worker Neil Burridge was mentioned. So, not long ago he was invited to participate in a project to study Bronze Age weapons, which was initiated by a group of archaeologists from Great Britain, Germany and China under the leadership of Raphael Hermann from the University of Göttingen.

The task of experimental archeology is to understand how certain products found by archaeologists during excavations were used in practice, as they were originally used. In particular, it is experimental archeology that can tell us how Bronze Age warriors fought with their bronze swords. To do this, copies of ancient weapons are created, after which specialists try to repeat the movements of ancient swordsmen.

Neil Burridge's swords used in experiments (Raphael Hermann et al. / Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 2020)

First of all, the origin of 14 types of characteristic dents and nicks that were found on swords of that era was established. It was possible to find out that the warriors clearly tried to avoid sharp blows so as not to damage the soft blades, but used the technique of crossing blades without hitting them against each other. But towards the end of the Bronze Age, it became noticeable that the marks were grouped more closely along the length of the blades. That is, it is obvious that the art of fencing has developed and swordsmen have learned to deliver more accurate blows. The article was published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory.

Sword blade after roughing and before polishing the blade

Polished blade, handle and pommel made of olive wood

Fully finished sword

Metal wear analyzes were then carried out. After all, bronze is a soft metal, so products made from it leave a lot of different marks, as well as scratches and nicks. And it’s from them that you can find out how this or that weapon was used. But then scientists increasingly test theoretical calculations in practice and try to obtain exactly the same marks on modern copies of ancient swords as on their originals.

Neil Burridge, who specializes in bronze weapons, was asked to make replicas of seven swords found in Britain and Italy, dating from 1300-925. BC. The composition of the alloy, its microstructure, and the microstrength of the manufactured replicas exactly matched the originals.

Then they found experienced swordsmen who struck with these swords, as well as with spear tips, on wooden, leather and bronze shields. Every blow and parry was recorded on video, and all the marks on the swords were photographed. Then all the marks that appeared on the swords during this experiment were compared with signs of wear on 110 extant Bronze Age swords from museum collections in Great Britain and Italy.

So the work with the goal of “looking into our” past, including the past of ancient swords and Bronze Age warriors, continues today and is by no means guesswork. The most modern research methods and instruments are used. So the secrets of the past are gradually becoming smaller...

American reenactor Matt Poitras created this armor of the Mycenaean era, for which he also ordered an F type sword from Neil Burridge!

In particular, it turned out that when the sword hit the surface of a leather shield, either the tip of the blade was crushed, or a long notch appeared on its sharpened surface. If a blow was parried with the flat side of the sword, the blade would be bent by about ten degrees and long scratches would appear on it. It is interesting that such traces were found on only four swords. This suggests that the warriors diligently avoided sharp blocking of blows, as it could lead to damage to the blade.

"The Shield of Clonbryn" Neil also made a copy of the leather shield from Clonbrin (the only leather shield from such an ancient era that has survived to this day - cost to order £350), and these were the shields that the fencers who participated in the experiment fought with

Original swords kept in museums showed many clusters of different marks, and there could be up to five such dents in a small area of the blade. And in total, 325 (!) clusters were found on 110 blades. And this is evidence that the Bronze Age warriors had perfect control of their weapons and very accurately hit their opponents with blows falling on the same section of the blade.

This is how this experiment was conducted...

The weapon of the experiment and its clear consequences...

By the way, the military of different countries argued for a very long time about which blows with cold weapons (cutting or piercing) pose the greatest danger. Moreover, in the same England, back in 1908, the cavalry was armed with... swords, citing the fact that you need to swing a saber, but with a sword you just need to stab, which is both faster and more effective!

English cavalry sword mod. 1908, used during the First World War.

PS The author and the site administration express their gratitude to Aron Sheps for providing color diagrams and illustrations.

PPS The author and the site administration express their gratitude to Neil Burridge for the opportunity to use photographs of his works.

Finding area

The process of the emergence of bronze swords as a separate type of weapon was gradual, from a knife to a dagger, and then to the sword itself. Swords have slightly different shapes due to a number of factors. For example, both the army itself of a state and the time when they were used are important. The range of finds of bronze swords is quite wide: from China to Scandinavia.

In China, the production of swords from this metal begins around 1200 BC. e., during the reign of the Shang Dynasty. The technological culmination of the production of such weapons dates back to the end of the 3rd century BC. e., during the war with the Qin dynasty. During this period, rare technologies were used, such as metal casting, which had a high tin content. This made the edge softer and therefore easier to sharpen. Or with a low content, which gave the metal increased hardness. The use of diamond-shaped patterns, which were not aesthetic, but technological, making the blade reinforced along its entire length.

Bronze swords of China are unique due to technologies in which high-tin metal was periodically used (about 21%). The blade of such a blade was super-hard, but broke when bent too much. In other countries, swords were made with a low tin content (about 10%), which made the blade soft and bending rather than breaking when bent.

However, iron swords supplanted their bronze predecessors; this happened during the reign of the Han Dynasty. China became the last territory where bronze weapons were created.

Secrets of the world and man

6 379

Bronze swords

Before the widespread use of iron and steel, swords were made of copper, and then bronze was made of alloys of copper with tin or arsenic. Bronze is very resistant to corrosion, which is why we have quite a lot of archaeological finds of bronze swords, although their attribution and clear dating are often very difficult.

Bronze is a fairly durable material that holds an edge well. In most cases, bronze with a tin content of about 10% was used, which is characterized by moderate hardness and relatively high ductility, but in China bronze with a tin content of up to 20% was used - harder, but also more fragile (sometimes only blades were made from hard bronze, and the inner part of the blade is made of softer material).

Bronze swords

Bronze is a precipitation-hardening alloy and cannot be hardened like steel, but can be significantly strengthened by cold deformation (forging) of cutting edges. Bronze cannot “spring” like hardened steel, but a blade made from it can bend within significant limits without breaking or losing its properties - having straightened it, it can be used again. Often, to prevent deformation, bronze blades had massive stiffening ribs. Long blades made of bronze were supposed to be especially prone to bending, so they were used quite rarely; the typical blade length of a bronze sword is no more than 60 centimeters. However, it is completely wrong to call short bronze swords exclusively piercing - modern experiments, on the contrary, have shown a very high cutting ability of this weapon; its relatively short length limited only the combat distance.

Bronze sword

Since the main technology for processing bronze was casting, it was relatively easy to make a more effective, complexly curved blade from it, so bronze weapons of ancient civilizations often had a curved shape with a one-sided sharpening - this includes the ancient Egyptian khopesh, the ancient Greek makhaira and the kopis borrowed by the Greeks from the Persians. It is worth noting that, according to the modern classification, all of them belong to sabers or cutlasses, and not swords.

Khopesh

Mahaira

Kopis (modern replica)

The title of the oldest sword in the world today is claimed by a bronze sword, which was found by Russian archaeologist A.D. Rezepkin in the Republic of Adygea, in a stone tomb of the Novosvobodnaya archaeological culture. This sword is currently on display in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. This bronze proto-sword (total length 63 cm, hilt length 11 cm) dates back to the second third of the 4th millennium BC. e. It should be noted that by modern standards this is more of a dagger than a sword, although the shape of the weapon suggests that it was quite suitable for slashing. In the megalithic burial, the bronze proto-sword was symbolically bent.

Bent Bronze Sword

Before this discovery, the most ancient swords were considered to be those found by the Italian archaeologist Palmieri, who discovered a treasure with weapons in the upper reaches of the Tigris in the ancient palace of Arslantepe: spearheads and several swords (or long daggers) from 46 to 62 cm long. Palmieri’s finds date back to the end of the 4th millennium.

The next major find is swords from Arslantepe (Malatya). From Anatolia, swords gradually spread to both the Middle East and Europe.

Sword from the town of Bet Dagan near Jaffa, dating back to 2400-2000 BC. e., had a length of about 1 meter and was made of almost pure copper with a small admixture of arsenic.

Copper sword from Bet Dagan, ca. 2400-2000 BC e. Kept in the collection of the British Museum

.Also very long bronze swords dating back to around 1700 BC. e., were discovered in the area of the Minoan civilization - the so-called “type A” swords, which had a total length of about 1 meter or even more. These were predominantly stabbing swords with a tapering blade, apparently designed to hit a well-armored target.

Modern reconstructions of various types of Mycenaean swords, including (the top two) - the so-called. type A.

Very ancient swords were found during excavations of monuments of the Harrapan (Indus) civilization, with dating according to some data up to 2300 BC. e. In the area of the ocher painted pottery culture, many swords dating back to 1700-1400 were found. BC e.

Sword, bronze, 62 cm, 1300-1100 BC. Central Europe

Bronze swords have been known in China since at least the Shang period, with the earliest finds dating back to around 1200 BC. uh..

Ancient Chinese bronze sword

Many Celtic bronze swords have been discovered in Great Britain.

Celtic bronze swords from the National Museum of Scotland.

Iron swords have been known since at least the 8th century BC. e, and began to be actively used from the 6th century BC. e. Although soft, non-hardening iron did not have any special advantages over bronze, weapons made from it quickly became cheaper and more accessible than bronze - iron is found in nature much more often than copper, and the tin necessary to obtain bronze in the ancient world was generally mined only in several places. Polybius mentions that Gallic iron swords of the 3rd century BC. e. often bent in battle, forcing owners to straighten them. Some researchers believe that the Greeks simply incorrectly interpreted the Gallic custom of bending sacrificial swords, but the very ability to bend without breaking is a distinctive feature of iron swords (made of low-carbon steel that cannot be hardened) - a sword made of hardened steel can only be broken , and not bend.

Ancient iron sword

In China, steel swords, significantly superior in quality to both bronze and iron, appeared already at the end of the Western Zhou period, although they did not become widespread until the Qin or even Han era, that is, the end of the 3rd century BC. e.

Chinese Tao sword from the late Qing Dynasty.

Around the same time, the inhabitants of India began to use weapons made of steel, including steel similar to welded Damascus. According to the periplus of the Erythraean Sea, in the 1st century AD. e. Indian steel blades arrived in Greece.

An Etruscan sword from the 7th century found in Vetulonia. BC e. was obtained by connecting several parts with different carbon contents: the inner part of the blade was made of steel with a carbon content of about 0.25%, the blade was made of iron with a carbon content of less than 1%. Another Romano-Etruscan sword of the 4th century BC. e. has a carbon content of up to 0.4%, which implies the use of carburization in its production. Nevertheless, both swords were of low quality metal, with a large number of impurities.

Etruscan swords

The widespread transition to blades made of hardened carbon steel took a long time - for example, in Europe it ended only around the 10th century AD. e. In Africa, iron swords (mambele) were used back in the 19th century (although it is worth noting that iron processing in Africa began very early, and with the exception of the Mediterranean coast, Egypt and Nubia, Africa “jumped” the Bronze Age, immediately switching to iron processing).

Mambele

The following types of piercing-cutting swords received the greatest fame in classical antiquity:

-Xiphos

Xiphos (modern replica)

An ancient Greek sword with a total length of no more than 70 cm, the blade is pointed, leaf-shaped, less often straight;

-Gladius

Gladius

The general name for all swords among the Romans, today is usually associated with the specific short sword of the legionnaire;

-Akinak

Akinak

Scythian sword - from VII BC. e.;

-Mitsiya

Mitsiya

Meotian sword - from the 5th to the 2nd centuries. BC e.

Later, the Celts and Sarmatians began to use cutting swords. The Sarmatians used swords in equestrian combat, their length reached 110 cm. The crosshair of the Sarmatian sword is quite narrow (only 2-3 cm wider than the blade), the handle is long (from 15 cm), the pommel is in the shape of a ring.

Sarmatian swords

Spata, which is of Celtic origin, was used by both foot soldiers and horsemen. The total length of the spatha reached 90 cm, there was no crosspiece, and the pommel was massive and spherical. Initially, the spat had no tip.

Modern reconstruction of a cavalry spatha of the 2nd century AD. e.

In the last century of the Roman Empire, spathas became the standard weapon of legionnaires, both cavalry and (a shorter version, sometimes called semispatha) infantry. The latter option is considered transitional from the swords of antiquity to the weapons of the Middle Ages.

via

Scythian weapons

Bronze swords of the Scythians have been known since the 8th century BC. e., they had a short length - from 35 to 45 cm. The shape of the sword is called “akinak”, and there are three versions about its origin. The first says that the shape of this sword was borrowed by the Scythians from the ancient Iranians (Persians, Medes). Those who adhere to the second version argue that the prototype of the Scythian sword was a weapon of the Kabardino-Pyatigorsk type, which was widespread in the 8th century BC. e. on the territory of the modern North Caucasus.

Scythian swords were short and primarily intended for close combat. The blade was sharpened on both sides and shaped like a highly elongated triangle. The cross-section of the blade itself could be rhombic or lenticular; in other words, the blacksmith himself chose the shape of the stiffener.

The blade and handle were forged from one piece, and then the pommel and crosshair were riveted to it. Early examples had a butterfly-shaped crosshair, while later ones, dating back to the 4th century, were already triangular in shape.

The Scythians kept their bronze swords in wooden sheaths, which had buterols (the lower part of the sheath), which were protective and decorative. Currently, a large number of Scythian swords have been preserved, found during archaeological excavations in various mounds. Most of the specimens are preserved quite well, which indicates their high quality.

Predecessors

Before the advent of bronze, stone (flint, obsidian) was used as the main material for cutting tools and weapons. However, the stone is very fragile and therefore not practical for making swords. With the advent of copper, and subsequently bronze, daggers could be forged with a longer blade, which eventually led to a separate class of weapon - the sword. Thus, the process of the appearance of the sword as a derivative weapon from the dagger was gradual. In 2004, examples of the first swords from the Early Bronze Age (c. 33rd to 31st centuries BC) were claimed, based on finds at Arslantepe by Marcella Frangipane of the University of Rome. A cache of that time was found, which contained a total of nine swords and daggers, which included an alloy of copper and arsenic. Among the finds on three swords was beautiful silver inlay.

These exhibits, with a total length of 45 to 60 cm, can be described as either short swords or long daggers. Several other similar swords have been found in Turkey and are described by Thomas Zimmerman.

Sword production was extremely rare for the next millennium. This type of weapon became more widespread only with the end of the 3rd millennium BC. e. Swords from this later period can still be readily interpreted as daggers, as is the case with a copper example from Naxos (dated c. 2800 - 2300 BC), measuring just under 36 cm in length, but individual examples of the Cycladic civilization "copper swords" period approximately 2300 years. reach a length of up to 60 cm. The first examples of weapons that can be classified as swords without ambiguity are blades found on Minoan Crete, dated to approximately 1700 BC, their length reaches a size of over 100 cm. These are swords of the Aegean "type A" Bronze Age.

Roman weapons

Bronze swords of Roman legionnaires were very common at that time. The most famous is the sword gladius, or gladius, which later began to be made of iron. It is assumed that the ancient Romans borrowed it from the Pyrenees and then improved it.

The tip of this sword has a fairly wide sharpened edge, which had a good effect on cutting characteristics. These weapons were convenient to fight in dense Roman formations. However, the gladius also had disadvantages, for example, it could deliver slashing blows, but they did not cause serious damage.

Out of order, these weapons were very much inferior to German and Celtic blades, which were longer. The Roman gladius reached a length of 45 to 50 cm. Subsequently, another sword was chosen for the Roman legionaries, which was called the “spata”. A small amount of this type of bronze sword has survived to this day, but their iron counterparts are quite sufficient.

The spatha had a length of 75 cm to 1 m, which made it not very convenient to use in close formation, but this was compensated for in a duel in free territory. It is believed that this type of sword was borrowed from the Germans, and later slightly modified.

The bronze swords of Roman legionaries - both gladius and spatha - had their advantages, but were not universal. However, preference was given to the latter due to the fact that it could be used not only in foot combat, but also while sitting on a horse.

Armor from 1300 BC e.

Bronze can be used both for protection and as a tool of aggression.

In Mycenae, from about 1300 BC, warriors rode chariots and wore bronze armor, although leather was still preferred. This is the period reflected in Homer's Iliad, but the shining armor described there is the fruit of heroic fantasy. The reality, as far as it has been preserved, only vaguely resembles the elements of protection described in the book.

The earliest known armor was found in the Mycenaean tomb at Dendra. The helmet is a pointed cap, skillfully made from pieces of boar tusk. Bronze cheek flaps are suspended from it, reaching a full circle of bronze around the neck. Curved sheets of bronze cover the shoulders. Beneath these is a breastplate, and then three more circles of bronze plate, suspended from one another to form a semi-rigid, thigh-length skirt. Leggings, also made of bronze, complement the armor.

The weapons of the Mycenaean warrior were a bronze sword and a spear with a tip made of the same material. His shield is made of tough leather on a wooden frame. Similar weapons were used several centuries later by Greek hoplites.

Swords of Ancient Greece

Bronze swords of the Greeks have a very long history. It originates in the 17th century BC. e. The Greeks had several types of swords at different times, the most common and often depicted on vases and in sculpture is the xiphos. It appeared during the Aegean civilization around the 17th century BC. e. Xiphos was made of bronze, although later it began to be made of iron.

It was a double-edged straight sword, which reached approximately 60 cm in length, with a pronounced leaf-shaped tip, it had good chopping characteristics. Previously, xiphos was made with a blade up to 80 cm long, but for inexplicable reasons they decided to shorten it.

In addition to the Greeks, this sword was also used by the Spartans, but their blades reached a length of 50 cm. Xiphos was used by hoplites (heavy infantry) and Macedonian phalangites (light infantry). Later, these weapons became widespread among most of the barbarian tribes that inhabited the Apennine Peninsula.

The blade of this sword was forged immediately along with the hilt, and later a cross-shaped guard was added. This weapon had a good cutting and piercing effect, but due to its length, its slashing characteristics were limited.

War in the Bronze Age

Bronze Age Warrior

During the Bronze Age, several types of “classical” weapons appeared, which lasted throughout the subsequent millennia until very recently. These are a sword and a spear as offensive weapons and a shield, helmet and shell as elements of armor. For fast movement, two-wheeled, horse-drawn war chariots were invented, which, together with the crew - a driver and an archer - constituted a fast and deadly fighting machine.

This combination of these military innovations led to social transformations everywhere, as they changed not only the conduct of combat and war itself, but also the underlying social and economic conditions. There was a need for new abilities and new craftsmen, such as those who could make the horse harness with which the driver could maneuver the war chariot, or those who could build the chariot itself. In addition, dexterity in handling new types of hand weapons - a sword and a spear - was now necessary, which required long and lengthy training, which can be judged, for example, by the highly developed shoulders of skeletons from the early Mycenaean burials of Aegina. Remains in Bronze Age burials often have wounds inflicted by a sword or spear, and the weapon itself often shows signs of combat use - damage and repeated sharpening. An organized and deadly method of warfare entered the historical arena.

Il. 1. Bronze Age warrior, reconstructed based on funerary goods and textiles found in Danish oak coffins

The new military aristocracy differed from their fellow tribesmen in their clothing and well-groomed appearance. There was a need for razors and tweezers, which helped maintain this look; in addition, the new elite sported luxurious woolen raincoats (ill. 1). It would not be a mistake to assume that warfare as a profession has been actively developing since the Middle Bronze Age. The status of a warrior was especially attractive to young men, which forced them to serve as mercenaries in very remote areas. In the cemetery in Neckarsulm in southern Germany, more than a third of male burials, even without weapons in the grave goods, are the remains of non-local, alien men. Globalization was also reflected in the widespread proliferation of new types of swords. Thus, a sword with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle for the period from 1500 to 1100 BC. e. spread from Scandinavia to the Aegean Islands, which indicates an intensive exchange of knowledge in the field of military and combat practice, as well as long journeys of warriors and mercenaries (ill. 2).

War chariots

In all likelihood, war chariots appeared in the southern Russian steppes, then, in the period between 2000 and 1700 BC. e. they spread from the region of the Eastern Urals and the Sintashta culture to the Black Sea region, the islands of the Aegean Sea and further to Central and Northern Europe, where very realistic and detailed images of war carts are found in rock paintings. The kingdoms and palace cultures of the Middle East, the Hittites in Anatolia and the Mycenaeans in Greece, especially readily adopted the new product. The aristocratic style of fighting became widespread: first spears were used, and then rapiers and swords up to a meter long. They were used primarily as piercing rather than slashing weapons, this is illustrated by Mycenaean seals and inlays on blades, which depict a piercing attack on the enemy’s shield. It is clear that the sword was the weapon of the elite, the leader, who, however, was always accompanied by a large group of foot soldiers with spears and probably bows and arrows to hit distant targets. In Germany and Denmark - regions in which settlements and necropolises of the Bronze Age are well studied - it is possible to calculate how many warriors from individual households supported the few leaders with swords: the ratio is 6-12 warriors per leader. This coincides with the number of oarsmen on Scandinavian cave paintings with ships and can be considered a stable number of warriors in a group under a local leader (Fig. 3).

| Il. 2. Distribution of cheekpieces for horse harnesses of war chariots between 2000 and 1600. BC e. | Il. 3. Rock art from Frønarp in Southern Sweden depicting war chariots |

Fortified Settlements

At the same time, in the Danube-Carpathian region there was a widespread strengthening of large settlements located on the ground with the help of ramparts and deep ditches. This shows how organized the preparations were for local conflicts; Large groups of warriors provided constant protection of people and property. Many of these fortified settlements are located at crossroads near large rivers or mountain passes, suggesting that they were needed to ensure the security of the metal trade. In some places the fortifications were made of large solid stones, this is especially impressive at Moncodonier in Metri and where even the gates were separately protected by a complex stone structure, which is sometimes found in Central European fortifications. On the northern Italian Pa and a certain plain there are also defensive structures of complex design, where water ditches are built around the settlements (Fig. 4).

Fortifications existed throughout the Bronze Age, and there is an explanation for this. Near some, for example, near Velem in Bohemia, those killed in battle were found, dumped in large numbers into pits. Further excavations of Bronze Age fortifications will probably yield the same results.

Il. 4. a – Terramare settlement with palisade, Poviglio, Italy (after: Bernabó Brea 1997); b – Fortress Gate, Moncodonia, Istria (by: Mihovilic i. a. o. J.)

Swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the hilt

Il.

5. Swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching a handle of the same type, common in the territory between Denmark and the Aegean region. The most ancient swords were practically unsuitable for combat, since the blade and handle were connected to each other only with rivets. Soon an effective and powerful weapon appeared, in which the handle and blade were cast as one piece. The handle itself, made of wood, bone or horn, which ended with a pommel, was attached to a tongue-shaped platform. Such a sword could reflect strong blows and not break when hit by a shield. The new sword, with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the hilt, became the standard weapon of the Bronze Age warrior, and it spread over a vast area from Scandinavia to the Aegean islands, indicating intense connections between groups of mercenaries or even between entire Bronze Age societies. It continued to be used in different variations of shape and length until the very end of the Bronze Age.

In Central Europe, a blade length of 60 cm was preferred. Some blades found were slightly shorter, indicating repeated sharpening of the tip, which could often bend or break. This length of the sword indicates, rather, in favor of individual combat rather than phalanx attacks. In the Aegean region, the length of the sword, after some fluctuations, became 40 cm, like the later Roman gladius, which speaks in favor of fighting in a phalanx with limited movement (ill. 5).

Darts and spears

The most common weapons of the Bronze Age were undoubtedly javelins and spears, which only at the end of this period began to be quite distinctly different from each other. The latter, like modern bayonets, were used in close combat and were par excellence infantry weapons. Each warrior usually carried two javelins or spears, as evidenced by images on Mycenaean vases, as well as grave goods found throughout Europe.

Defensive weapons: shield, helmet and armor

A warrior's best protection from injury has always been his own skillful handling of weapons. Therefore, the Celts went into battle naked to demonstrate their military superiority and fearlessness. However, even the best warrior needed protection from all sorts of surprises, and along with the progress of weapons, defensive equipment also improved.

Outside Greece, almost no defensive equipment was found in finds dating from the Early and Middle Bronze Ages, since they were made mainly of wood or leather (shields) and bone (wild boar tusks for helmets). The best sources available to us on this topic are Mycenaean depictions of warfare. Helmets with boar tusks from the Middle Bronze Age were found in the Carpathian region. Nevertheless, in Central Europe, some elements of men's equipment were probably developed specifically for protection in battle: wrist spirals and heavy spiral rings protecting the hand and elbow were often found along with swords. There is no doubt that they were used as they show mechanical damage. Conventional wrist spirals were shaped like the forearm and tapered towards the wrist.

Only towards the end of the Bronze Age, special protective equipment made of unforged bronze appeared throughout Europe - helmets, shields, armor and leggings. Since unforged bronze did not provide the necessary protection, this equipment was considered the prestigious vestment of the military aristocracy, used exclusively for ceremonies and to demonstrate their social status. This conclusion coincides with the observation of researchers that leaders with cast-hilted swords did not take part in heavy battles. In addition, this confirms the presence of a hierarchy in the conduct of military operations in the Late Bronze Age - the battle was primarily taken on by warriors, and the elite directed their actions.

Nevertheless, some usefulness of defensive equipment cannot be ruled out. The armor and leg armor were probably lined on the inside with leather or other organic materials such as felt or linen, as evidenced by fastening rivets. In Greece, helmets, leg plates and wrist guards also had holes for attaching linings. It can be assumed that the situation was the same in the rest of Europe. In addition, one of the most famous helmets dating back to the Late Bronze Age, the helmet from Hajdu-Bösörmei is covered with dents from blows of a sword and ax or arrows and darts. Judging by the rivet holes on the inside, the helmet had a lining of leather or fabric, thanks to which it sat firmly and comfortably on the head.

Bronze swords: functionality and use

One of the constantly repeated arguments against the fact that both cast and tongue-shaped swords were actually used in warfare is the claim that the hilt itself is too short to be held in the hand. Having held hundreds of swords in my hand, I find this argument to be unfounded. Iron Age swords are quite heavy, at least compared to historical or modern rapiers, with most of the weight being in the blade. To control the movements of the sword, you need to clasp the handle very tightly with your palm. This is precisely what the short handle with protruding shoulders, which in this case are the functional part of the handle, is designed for. The hand covered the handle along with the hanger, making all movements more precise and controlled. Fingers in such a coverage also became more mobile, which made it possible to use a variety of military techniques. This was an ideal solution for a combination of slashing and stabbing attacks carried out with one hand. During the Late Bronze Age, the cutting technique became dominant and made handling the sword even more difficult, leading to one interesting invention (Fig. 6). Most swords with a cast hilt have a small hole in the pommel, the purpose of which has not yet been explained. However, some swords have abrasions in the area of this hole, clearly caused by a strap, most likely leather. On ill. b shows the use of this cord, which makes one recall a modern police baton, since such a device for the handle of a sword corresponded to the same practical functions: it prevented the ability to release the sword from the hand, allowed the hand to relax, and the warrior to use a larger swing and greater force when striking.

Il. 6. A sword with a fused hilt, equipped with a leather strap that did not allow the weapon to be released from the hand

Proper balancing plays an essential role in sword fighting. The distribution of weight between the handle and the blade determines its use for stabbing or slashing. The long and thin blades of the Middle Bronze Age speak more about their use as a piercing weapon, and in the Late Bronze Age the blade became wide and heavy, which was necessary for a chopping weapon. The difference lies in the location of the center of gravity: for thrusting swords it is located next to the hilt, for cutting swords it is much lower, in the area of the blade.

This means that the piercing sword had to make it possible to make quick defensive and offensive movements, and the slashing sword was too heavy for this, it was intended for energetic movements with a large swing. It should be emphasized, however, that the cutting and thrusting swords of the Bronze Age cannot be compared with modern types of swords, which are very highly specialized and suitable only for their originally intended use. The Bronze Age sword could be used in a variety of ways, despite the fact that one of the functions of a piercing or cutting weapon could be realized by one sword better than by another. Only the earliest examples of rapiers are purely piercing weapons, even compared to the most ancient swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the hilt.

All of the above shows that swords were indeed used in battles in the Bronze Age. This is confirmed by traces of combat on the blades, which can be found on most swords. Such notches and subsequent re-sharpening are characteristic of swords throughout the Bronze Age. The area under the handle is a protection zone, so this is where particularly severe damage and sharpening marks are found. Most often, the defects are more pronounced on one side than on the other, since the warrior usually always held the weapon in his hand in the same way. The consequence of repeated sharpening was that the blades under the hilt often became narrower, they were sharpened more strongly.

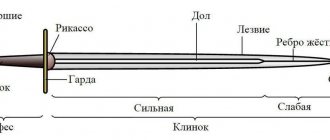

Older swords, which had been used longer in combat and were more frequently damaged and repaired, sometimes had the lower crosshairs broken due to repeated sharpening and the fury of enemy blows. Therefore, the lower rivet holes were damaged and unusable. In the Late Bronze Age, this led to technical improvements in swords, in particular to the appearance of a ricasso under the hilt, which helped to hold the enemy blade so that it did not slip upward, damage the crosshairs and injure the warrior’s fingers. Sometimes the entire handle was bent due to frequent strikes and defensive techniques, indicating that heavy fighting was not uncommon. Swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle could even break in the area of the handle. The findings show that this happened very often, even if you do not count some broken swords found, in which the breakage could have happened in recent times.

In the middle part of the blade there is damage that occurs during an attack when the striking sword is stopped by the enemy’s sword. Here, too, there may be concavities in the cutting edge that appear due to repeated sharpening. These concavities are especially noticeable in comparison with swords that have damage that has not been corrected by re-sharpening (ill. 7). Some swords have oblique notches on the middle edge, indicating that Bronze Age warriors also used defensive techniques that used the flat surface of the blade. The tip of the blade could also be bent or even broken off when the sword hit the shield during a stabbing blow. Sharpening with the formation of a new point is quite common in swords dating back to the Middle Bronze Age, although it is also characteristic of the Late Bronze Age, which indicates the varied use of swords - both for chopping and piercing.

Il. 7. Examples of swords with a re-sharpened and modified blade

To summarize, we can say that we have clear evidence of the great importance of sword fighting in Bronze Age Europe. Throughout this period, there were well-trained experts in the art of sword fighting. It can be stated that different types of swords also had different functions: a sword with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle was the standard weapon of professional warriors, and a sword with a cast handle was more of a leader’s weapon, although it was also used in battle. In swords of this type, the blade is usually damaged to a much lesser extent than in swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle. Regarding the Early and Middle Bronze Age, further evidence of this use of fused hilt swords is the fact that the hilt was secured only with rivets, which could hardly withstand a strong blow. In the Late Bronze Age, the end of the blade was already inserted into the hilt to make the weapon more stable and prevent the sword from breaking between the blade and the hilt. Therefore, the number of rivets was reduced to two, and very small ones. It can be assumed that at this time swords with cast hilts were more often used in real combat. The damage found on both the tongue-shaped swords and the cast-handle swords does not resemble those that could occur when using the swords in practice combat. For them, real swords were too valuable, so special wooden swords were used for training already in the Bronze Age, which, in turn, also indicates the great importance of war in the lives of Bronze Age people.

Nomadic warriors and their significance for the metal trade

During the Bronze Age, an international warrior culture emerged for the first time, testifying to the intense relationships and active mutual influence of various groups of warriors throughout Europe. This can be illustrated using maps of the distribution of different types of swords, for example, swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the hilt or swords with a cast octagonal hilt from the 15th and 14th centuries before. n. e., uniting Denmark with Southern Germany and Central Europe (ill. 8). In addition, the mapping clearly demonstrates that some women were used to establish political alliances between local groups and establish peaceful relations, which were necessary for the metal trade and allowed traders and warriors to move safely between neighboring groups. Il. Figure 8 shows, among other things, that male warriors left home much more often and moved longer distances from it.

Il. 8. The spread of octagonal swords as an indication of the movements of mercenaries and traders in the 15th and 14th centuries. BC e. The circles represent individual cultural groups, and the arrows show places where the woman was buried outside her home region

Such movements were recently confirmed by the discovery of a men's cemetery in Neckarsulm, where more than fifty people were buried. By studying strontium isotopes in tooth enamel, it was possible to prove that a third of the men buried there were from other places. Most likely, these were mercenaries in the service of a foreign ruler. Traders, blacksmiths, warriors, mercenaries, migrants and diplomats traveled long distances in those days. Good examples here would be the remains of ships discovered at capes Ulu-Burun and Gelidonya. These ships could transport not only goods to distant possessions, but also warriors or mercenaries, who at the same time also protected the cargo.

It has been historically proven that Germanic and Celtic mercenaries served the Romans, returning after service to their homeland with Roman weapons and Roman goods, the possession of which ensured prestige in society. Therefore, the presence in the eastern part of Central Europe of the 14th and 13th centuries BC. e. Greco-Mycenaean weapons can well be interpreted as evidence of the return of mercenaries after service in Mycenaean territories. The same can be confirmed by Central European, primarily Italic, swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle, found in the area of Mycenaean palaces, as well as ceramics made in the traditions of the native places of the newcomers, for example, vessels reminiscent of Italic ones and discovered in the East Mediterranean.

Ethnographic examples support the thesis of warriors and traders moving over long distances. Warriors often formed their own group identity (warrior communities), which united them within a specific territory through clear rules of acceptable behavior. The rules could concern both the recruitment of new warriors and one’s own travels to distant lands in order to return with glory and prestigious goods. This behavior is characteristic of the Maasai and Japanese samurai, and is present as a recurring plot element in the stories of warriors and wars.

Organization of military units

In some regions of Europe, the proportion of weapons in burials and treasures is so high that it is possible to calculate how many weapons and warriors were available at a certain point in time. In Denmark from the period between 1450 and 1150 BC. e. About 2,000 swords have survived, almost all of which were found in burials. At this time, approximately 50,000 burial grounds were built, from 10 to 15% of which it was possible to explore and find funeral gifts there. Extrapolating from these data, we can conclude that in reality a total of almost 20,000 swords ended up in the necropolises. Based on the lifespan of the sword (30 years), then the warrior’s family needed from three to four swords per century, which for the three hundred years in question is 12-15 swords. This, in turn, gives a figure for the simultaneous use of swords - 1300, which approximately corresponds to the number of settlements in Denmark at that time. The sword was probably the weapon of the local leader, and his troops were armed with javelins, although some may also have carried a sword.

The ratio of the number of leaders with swords and the number of peasants and warriors in the detachment can also be calculated based on the number of settlements. Individual farms varied in size, with families ranging from 10 to 15 people. Based on one farm per square kilometer and the population of half of Denmark at that time, the total area of which was 44,000 square kilometers, then there should have been between 25,000 and 30,000 farms of varying sizes existing at the same time. The leader assembled a detachment of supposedly 20-25 farms. Thus, the rulers of even small groups of the population could quickly assemble an army of several hundred warriors. If only the largest households delegated warriors, then for each leader with a sword there were probably only 5-10 warriors, which corresponds more closely to data calculated for some parts of Germany and the number depicted on ships in cave paintings. Thus, it can be considered proven that European societies of the Bronze Age were very well armed. Throughout the era, the number of simultaneously existing weapons amounted to tens and hundreds of thousands, even if we take Denmark, a small but rich country, as the basis for calculations. Therefore, it is logical to assume that traces of military victims should also be preserved, and this assumption turns out to be fair.

Victims of war

Recently, our knowledge of battle wounds on skeletons has deepened significantly, as well as our understanding of the number of people killed in different types of conflicts.

Il. 9. Combat wound: bronze arrowhead in a vertebra. Klings, South Thuringia (after: Osgord i. a. 2000)

At the Olmo di Nogara cemetery in Northern Italy, dating back to the Middle Bronze Age, 116 male skeletons were examined, half of which were buried with swords with a tongue-shaped platform for attaching the handle, including early types with a short tongue. Approximately 16% of these people had injuries to the bones and skull caused by combat, most often blows from swords or arrows. If we consider that there are many fatal wounds inflicted by a spear or arrow that do not leave marks on the bones, then 16% will turn out to be a very high proportion, indicating constant local conflicts. In this region, warriors who had a sword actively participated in battles, which corresponds to the picture of burials with weapons in the arch of Mycenaean burials B, for those buried there have numerous wounds and a very short life expectancy.

However, there were also ruthless massacres. The fortification at Vilema in Bohemia has already been mentioned. Another example is Sund in Western Norway. A mass grave from the late Middle Bronze Age was discovered here, containing more than 30 people - men, women and children - killed around 1200 BC. e. The wounds indicate fierce combat between men who apparently fought with swords and many of whom had healed wounds from past battles. Some showed signs of malnutrition, suggesting that control of food sources may have been a factor in the war.

Il. 10. Wooden club and skull with marks from a blow from a club, discovered on a Bronze Age battlefield in the Tollensee River valley (photo: Office of Culture and Monument Protection of the State of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Department of Archeology, Schwerin)

Finally, we must mention the great battle that also took place around 1200 BC. e. in the valley of the small river Tollensee in present-day Mecklenburg, Vorpommern. Here, on a section of the river 1-2 kilometers long, the remains of the skeletons of more than a hundred people were found, and it is likely that others will be discovered in the future (Fig. 9). Obviously, here, after a lost battle, all the dead of the entire army were thrown into the river. The remains of wooden clubs and axes (Fig. 10), as well as arrowheads, were found from weapons. It is likely that those who died were migrants looking for new lands, because at this time dramatic changes were taking place throughout Europe.

Thus, there is evidence of the existence of organized warfare, from small conflicts to confrontations of entire armies. In this sense, the Bronze Age was not much different from the subsequent Iron Age.

Conclusion

Even twenty years ago, research into Bronze Age weapons was aimed exclusively at elucidating their typological development, and their practical use was highly questioned. A new generation of researchers looked at the object of their study in a new way. Today, traces of its use on weapons have already been studied, reconstruction experiments have been carried out, showing how well organized and dangerous the fighting was in the Bronze Age, which is confirmed by anatomical studies of wounds. It is not far from the truth to say that modern methods of warfare have their origins in the Bronze Age, since the forms of weapons and defense systems known to us from later times were developed then.

Author: Christian Christiansen. War in the Bronze Age

European weapons

In Europe, bronze swords have been quite widespread since the 18th century BC. e. One of the most famous swords is considered to be the Naue II type sword. It got its name thanks to the scientist Julius Naue, who was the first to describe in detail all the characteristics of this weapon. Naue II is also known as the tongue-hilted sword.

This type of weapon appeared in the 13th century BC. e. and was in service with the soldiers of Northern Italy. This sword was relevant until the beginning of the Iron Age, but it continued to be used for several more centuries, until approximately the 6th century BC. e.

Naue II reached a length of 60 to 85 cm and was found in the territories of what is now Sweden, Great Britain, Finland, Norway, Germany and France. For example, a specimen that was discovered during archaeological excavations near Brekby in Sweden in 1912 reached a length of about 65 cm and belonged to the period of the 18th-15th centuries BC. e.

The shape of the blade, which was typical for swords of those times, is a leaf-shaped formation. In the IX-VIII centuries BC. e. Swords with a blade shape called “carp tongue” were common.

This bronze sword had very good characteristics for this type of weapon. It had wide, double-edged edges, and the blades were parallel to each other and tapered towards the end of the blade. This sword had a thin edge, which allowed the warrior to inflict significant damage to the enemy.

Due to its reliability and good characteristics, this sword became widespread throughout most of Europe, as confirmed by numerous finds.

Aegean period

Minoan and Mycenaean (mid to late Aegean Bronze Age) swords are classified into types labeled A through H as follows by Sandars (British archaeologist), in Sandars's "typology" (1961). Types A and B ("shank-loop") are the earliest, from about the 17th to 16th centuries. BC e. Types C ("horned swords") and D ("cross swords") from the 15th century BC, types E and F ("T-hilt swords") from the 13th and 12th centuries BC AD The 13th to 12th centuries also saw a revival of the "horned" type of sword, which were classified as types G and H. Type H swords are associated with the Sea Peoples and were found in Asia Minor (Pergamon) and Greece. Contemporary with types E and H is the so-called Naue II type, imported from South-Eastern Europe.

Andronovo swords

Andronovtsy is the common name for various peoples who lived in the 17th-9th centuries BC. e. in the territories of modern Kazakhstan, Central Asia, Western Siberia and the Southern Urals. Andronovo people are also considered Proto-Slavs. They were engaged in agriculture, cattle breeding and handicrafts. One of the most common crafts was working with metal (mining, smelting).

The Scythians partially borrowed some types of weapons from them. The bronze swords of Andronovo were distinguished by the high quality of the metal itself and its combat characteristics. The length of this weapon reached from 60 to 65 cm, and the blade itself had a diamond-shaped stiffener. The sharpening of such swords was double-edged, due to utilitarian considerations. In battle, the weapon became dull due to the softness of the metal, and in order to continue the battle and inflict significant damage on the enemy, the sword was simply turned in the hand and the battle continued again with a sharp weapon.

The Andronovites made scabbards of bronze swords from wood, covering their outer part with leather. The inside of the scabbard was sealed with animal fur, which contributed to the polishing of the blade. The sword had a guard that not only protected the warrior’s hand, but also securely held it in its sheath.

Weapons and armor of soldiers of the Trojan War. Part 10. Replicas of swords

Home » Real story » Mysteries of the history of the distant past » Weapons and armor of the soldiers of the Trojan War. Part 10. Replicas of swords

Mysteries of the history of the distant past

byakin 01.10.2019 2080

15

in Favoritesin Favoritesfrom Favorites 8

I was about to finish the topic of the Trojan War, but active VO users pointed out a number of circumstances that simply oblige me to continue this topic. Firstly, with a fairly complete presentation of factual material based on archaeological finds, the “people” wanted to know about the tactics of use and especially the effectiveness of certain types of weapons of the Mycenaean era. It is clear that a science such as historiography cannot directly answer this question, but answers only through the works of some authoritative authors. Secondly, controversy arose regarding the actual technology of bronze. It seemed to someone that the bronze rapier was as heavy as a five-liter container of water, someone argued that bronze could not be forged, in a word, and here the opinion of experts in this field was needed. Still others were interested in shields, their design, ability to resist blows from bronze weapons, and weight.

That is, it was necessary to turn to the opinion of reenactors, moreover, authoritative people, “with experience”, who could confirm something from experience and refute something. My friends who found bronze figures were not suitable in this case: they are artists, not technologists, and do not know the specifics of working with metal, and besides, they hardly work with weapons. And I needed people who had access to famous museums and their collections, who worked on their artifacts, and made remakes to order. The quality of their work (and reviews of it) had to be appropriate - that is, the opinion of “armchair historians” regarding their products had to be high.

Modern replica bronze swords: above is a type H sword and below is a type G

After much searching, I managed to find three specialists in this field. Two in England and one in the USA and obtain permission from them to use their text and photographic materials. But now regulars of VO and simply its visitors have a unique opportunity to see their work, get acquainted with the technologies and their own comments on this interesting topic.

Neil Burridge with an "antenna sword" in his hands

I'll start by giving the floor to Neil Burridge, a Briton who has been working with bronze weapons for 12 years. He considers it his worst insult when “experts” come to his workshop and say that they would make exactly the same sword on a CNC machine in half the time and, accordingly, for half the cost.

“But it would be a completely different sword!”

– Neil answers them, but he doesn’t always convince. Well, they are stubborn ignoramuses and ignoramuses in England too, and nothing can be done about it. Well, seriously, he shares the opinion of the English historian of the 19th century. Richard Burton, what

“The history of the sword is the history of mankind.”

And it was precisely bronze swords and daggers that created this story, becoming the basis, yes, exactly the basis of our modern civilization, based on the use of metals and machines!

CI type sword. Length 74 cm. Weight 650 g. As you can see, the “rapiers” of that time were not heavy at all and, therefore, they could be used for fencing. And in general, bronze swords were no heavier than iron ones!

Analysis of the finds shows that the most ancient “rapiers” of the 17th and 16th centuries. BC. were also the most difficult if we consider the profile of the blade. They have a lot of ribs and grooves. Later blades are much simpler. And this weapon is piercing, since the blades had a wooden handle connected to the blade with rivets. Later, the handle began to be cast together with the blade, but very often, according to tradition, the convex heads of the rivets on the guard were preserved, and the guard itself was the holder of the blade!

Mycenaean solid bronze sword

Swords were cast in stone or ceramic molds. Stone ones were more difficult, and in addition, the sides of the blade were slightly different from each other. Ceramic ones could be detachable, or they could be solid, that is, they work using the “lost shape” technology. The base for the mold could be made of wax - two completely identical halves cast in plaster!

Author's clay mold

The copper (and the Homeric Greeks did not distinguish between bronze, for them it was also copper!) alloy used in later swords (there was nothing in the early ones!), consisted of approximately 8-9% tin and 1-3% lead. It was added to improve the fluidity of bronze for complex castings. 12% tin in bronze is the limit - the metal will be very brittle!

As for the general direction of the evolution of the sword, it definitely moved in the direction from a piercing rapier sword to a chopping leaf-shaped sword with a hilt that is a continuation of the blade! It is important to note that metallographic analysis shows: the cutting edge of the blade of bronze swords was always forged to increase its strength! The sword itself was cast, but the cutting edges were always forged! Although it was clearly not easy to do this without damaging the numerous ribs on the blade! (Those who wrote about this in the comments - rejoice! This is exactly what happened!) Therefore, the sword was both flexible and rigid at the same time! Tests have shown that such a leaf-shaped sword with one blow is capable of cutting a five-liter plastic container of water in half with an oblique blow!

Bronze leaf sword

What does a sword look like when it comes out of the mold? Badly! This is how it is shown in our photo and it takes a lot of time and effort to turn it into a product pleasing to the eye!

Freshly cast blade

Having removed the flash, we proceed to grinding, which is now performed using an abrasive, but in those distant times it was performed with quartz sand. But before polishing the blade, remember that at least 3 mm of its cutting edge must be well forged! It should be noted that only some swords of that time were absolutely symmetrical. Apparently, symmetry did not play a big role in the eyes of the gunsmiths of that time!

Beginning of blade processing

This is what a fully prepared blade with all the details looks like. Now all this needs to be connected with rivets and think about one more thing - regular cleaning of the blade, since polished bronze becomes dull at the slightest touch of fingers

Author's note: It's amazing how our lives move in zigzags! In 1972, during my first year at the pedagogical institute, I became interested in Mycenaean Greece and Egypt. I bought two gorgeous albums with photographs of artifacts and decided... to make myself a bronze dagger modeled on an Egyptian one. I cut it out of a bronze sheet 3 mm thick, and then, like a convict, I filed the blade until I got a leaf-shaped profile. The handle was made from... “Egyptian mastic”, mixing cement with red nitro varnish. I processed everything, polished it and immediately noticed that you should not touch the blade with your hands! And then I saw that the Egyptians’ “mastic” was blue (they considered red to be barbaric!) and I immediately stopped liking the dagger, despite the abyss of labor. I remember I gave it to someone, so, most likely, someone still has it in Penza. Then I made a bronze mirror for my future wife, and she really liked it. But I had to clean it very often. And now, after so many years, I am again turning to this same topic and writing about it... Amazing!

The handle parts are made of wood on a metal base with rivets and this is a labor-intensive and responsible operation, since if the wood is fragile (and in this case you need to use elm, hornbeam or beech) then blows from a hammer can easily damage it!

The finished sword by Neil Burridge

It is clear that Neil tried to reproduce, if not the entire typology of Sandars swords, then at least the most impressive examples from it.

Mycenaean short sword type B. Length 39.5 cm. Weight 400 g.

Type G sword found in the Mycenaean acropolis. Length 45 cm.

A fully finished G-type sword with a "horned crosshair". The price of the blade is 190 pounds, and a fully crafted sword with a gold ring on the hilt will cost you 290!

Type F (large) sword. Length 58 cm. Weight 650 g.

Sword of the classic Naue II type from the late Achaean era, common throughout Europe.

The author would like to thank Neil Burridge (https://www.bronze-age-swords.com/) for providing photographs of his work and information.

source: https://topwar.ru/83889-troyanskaya-voyna-i-ee-rekonstrukciya-sedmaya-chast.html

Types of swords

During the Bronze Age, there was a wide variety of types and types of swords. During their development, bronze swords went through three stages of development.

- The first is a bronze rapier of the 17th-11th centuries BC. e.

- The second is a leaf-shaped sword, with high piercing-cutting characteristics of the 11th-8th centuries BC. e.

- The third is a Hallstadt type sword from the 8th-4th centuries BC. e.

The identification of these stages is due to various specimens found during archaeological excavations in the territory of modern Europe, Greece and China, as well as their classification in catalogs of bladed weapons.

Bronze swords of antiquity, related to the rapier type, first appeared in Europe as a logical development of a dagger or knife. This type of sword arose as an elongated modification of the dagger, which is explained by practical combat needs. This type of sword primarily ensured the infliction of significant damage to the enemy due to its prickly characteristics.

Such swords were most likely made individually for each warrior, as evidenced by the fact that the hilt was of different sizes and the finishing quality of the weapon itself varied significantly. These swords are a narrow bronze strip that has a stiffening rib in the middle.

Bronze rapiers were intended to use piercing blows, but they were also used as slashing weapons. This is evidenced by notches on the blade of specimens found in Denmark, Ireland and Crete.

India

Swords have been found in archaeological remains of the Ocher Painted Pottery culture throughout the Ganges-Jamna Doab region. As a rule, weapons were made from copper, but in some cases from bronze. Various examples were discovered at Fatehgarh, where several varieties of handles were also discovered. These swords date from different periods, between 1700-1400. BC, but were probably used more widely during 1200-600 AD. BC. (during the Gray Painted Ware culture, Iron Age in India).

Swords XI-VIII centuries BC. e.

The bronze rapier, several centuries later, was replaced by a leaf-shaped or phallic-shaped sword. If you look at the photos of bronze swords, their difference will become obvious. But they differed not only in shape, but also in characteristics. For example, leaf-shaped swords made it possible to inflict not only stab wounds, but also chopping and cutting blows.

Archaeological research carried out in various parts of Europe and Asia suggests that such swords were widespread in the territory from what is now Greece to China.

With the advent of swords of this type, from the 11th century BC. e., it can be observed that the quality of decoration of the sheath and handle is sharply reduced, but the level and characteristics of the blade are noticeably higher than those of its predecessors. And yet, due to the fact that this sword could both stab and cut, and therefore was strong and did not break after a blow, the quality of the blade was worse. This was due to the fact that a larger amount of tin was added to bronze.

After some time, the shank of the sword appears, which is located at the end of the handle. Its appearance allows you to deliver strong slashing blows while keeping the sword in your hand. And so begins the transition to the next type of weapon - the Hallstadt sword.

Notes[edit]

- ↑

The Oldest Swords Found in Turkey - Frangipane, M. et.al. 2010: Collapse of the 4th millennium centralized system in Arslantepe and far-reaching changes in 3rd millennium societies. ORIGINI XXXIV, 2012: 237-260.

- ↑

Frangipane, "2002 Research Campaign in Arslantepe/Malatya" (2004) - The first swords uni-kiel.de

- "Student discovers 5,000-year-old sword hidden in Venetian monastery". LiveScience

. Retrieved March 25, 2022. - Shalev, Sariel (2004). Swords and Daggers in Late Bronze Age Canaan

. Franz Steiner Verlag. paragraph 62. ISBN 978-3-515-08198-6. - Benzi, Marion (2002). "Anatolia and the Eastern Aegean during the Trojan War". In Franco Montanari, Paola Asheri (ed.). Omero tremila Anni Dopo: IPK del Congresso di Genova, 6-8 Luglio 2000