From time immemorial, creating a sword was a very difficult task; even peoples such as the Vikings, Slavs and even the Italians did not produce the blades of their Carolingian swords, but ordered them from a German master who was located in the territory of modern France. I’ll make a reservation right away. We are talking about swords of the highest quality, which were forged exclusively for the elite. By the way, at that time, mainly noble people could own these weapons. By the way, to produce such masterpieces of weapons art, a special crucible steel was required, the secret of which was owned in India. Yes Yes. Imagine. The Vikings fought with weapons forged by a German master, and even from Indian steel. Now I have shocked half of the “residents” of the channel – those obsessed with knives.

I will definitely write about swords made of Indian steel in the next article about swords. This will be an excursion into the story of the greatest master - the blacksmith Ulfbert, whose mark adorned the swords of all noble rulers and great warriors, both in Rus' and the Scandinavian lands. Well, for now, we are talking about making a Romanesque sword in the Middle Ages.

Iron comes to Europe

Assyrian warriors with swords, on the scabbards of which characteristic “wings” are visible

. When we say that iron appeared in Europe at such and such a time, this does not mean at all that people immediately came up with the idea of replace them with bronze. For example, there is a lot of evidence that the tribes living in the Danube basin (the region of modern Austria and Hungary) were the first to discover the possibility of using iron, and from there they invaded Greece, where they destroyed the dominance of the city of Mycenae over the entire territory of the Aegean Sea. The culture that appeared here was called Hallstatt - again after the name of the place where its archaeological monuments were discovered, but historians are unable to say for sure who founded it, who these “people from Hallstatt” were. The famous British weapons historian Ewart Oakeshott even suggested that these same people with their new, improved weapons were mercenaries from Urartu and Assyria and that it was from there that they brought their knowledge with them. Be that as it may, they, just like the Mycenaeans, rode chariots, but their swords and scabbards were very similar to Assyrian ones! The shape of the swords of the “Hallstatt people” repeated many of the features of the early bronze ones, but differed in that they were intended for cutting blows and were to be used by the charioteers of war chariots. They had a large length and blade tips of a characteristic shape, which was clearly not intended for thrusting.

However, not everything is so simple here, because the types of swords across the vast territory of Europe, including in areas under the influence of the Hallstatt culture, were constantly changing. True, their main types that appeared between 950 and 450. BC, there were only three: a long bronze sword for slashing, then a heavy iron sword, which retained the shape of the bronze original, and, finally, a short iron sword, shaped like a leaf reed and slightly expanding towards the tip. But the Hallstatt swords themselves remained virtually unchanged and, moreover, had a very characteristic hilt, the pommel of which resembled... a Mexican hat!

Details of Hallstatt swords

Interestingly, one of these swords is 108 cm long from pommel to tip, meaning it most likely belonged to a horseman who needed to cut with a sword while standing on a chariot, and not to an infantryman for whom it was clearly too large. It’s interesting, but in addition to long ones, the Hallstatt people also had shorter swords, with poms in the shape of antennas bent in different directions, and one of them was again found in the Thames River, right in the middle of London! However, earlier swords with “antenna” pommels, made entirely of bronze, are also known. So this, apparently, is exactly the case when gunsmiths simply replaced one blade material with another, and left everything else unchanged.

Excavations in the burials of Hallstatt warriors do not give the slightest hint of how these long swords were worn, and it would be interesting to resolve this issue, since it could shed light on one curious detail of their scabbards, found in these same graves. In shape it resembles “wings” spread out to the sides, and they were located at the end of the sheath. At the same time, there are no signs of wear and friction on the ground, which means that these shackles did not touch the ground! And it was here that the English historian Ewart Oakeshott came up with the idea of how all this could be connected with ancient Assyria. It turns out that the Assyrians also had similar fittings on the ends of the scabbard, as evidenced by the figures from the bas-reliefs from the Assyrian palaces. At the same time, it is significant that the Assyrians’ swords hang on their belts in such a way that their hilts are directly at the chest - and it is clear why. After all, if a warrior fights while standing on a chariot, then the scabbard cannot dangle between his legs, because in this case he might trip over it and fall! Well, in this case the shackles were necessary as a support for the hand at the very moment when the long sword was snatched from the long sheath!

Damascus and damask steel: history of blade manufacturing

Surely you have heard about Damascus steel and damask swords. Legends have been made about this weapon for centuries, and the technology of forging the blade was kept secret. But the question is different. How did the first metallurgists, without modern knowledge, come up with the idea of combining layers of soft and hard steel together to make these blades? What did you get? It’s like a “sandwich” – a multi-layered piece. The metal for the knives was forged, folded, forged again, and these actions were repeated until the number of layers of metal reached one thousand, or even more. As a result, the weapon became hard and elastic at the same time. Next, the metal for the blades was polished, and stains characteristic of Damascus steel appeared on it - the result of multi-layering. Beautiful? Very.

Bulat was produced differently - high-carbon steel was used as a basis. It was practically cast iron, which retained the ability to forge. When melted, particles of low-carbon metal were added to it, which, when cooled, gave the weapon excellent cutting properties.

The shorter the better!

Infantry dagger-pugio in sheath

Then the Hallstatt people disappeared without a trace among numerous European nations, and the shape of the swords of the same Greeks began to be determined not by fashion, but solely by their tactics. The fact is that Greek warriors fought in a phalanx, hiding behind large painted shields. The phalanx consisted of 1000-1200 people along the front and eight rows deep, and the main weapons of its warriors were not swords, but spears. Swords were used to a limited extent, firstly, if a warrior’s spear broke, and secondly, in order to finish off an enemy who had been knocked to the ground - a motif very often found on ancient Greek vases. The swords had a length of 75-60 cm and were suitable for both thrusting and chopping, however, the Greeks had not only straight, but also single-edged curved swords - makhaira (another name is kopis), which originated from Spain. At the same time, as the coordination of the actions of the phalanx warriors developed, the length of the swords began to decrease, and this was especially noticeable in the army of Sparta, so that by 425-400. BC. they began to look less like swords and more like daggers. The Spartan king Agesilaus was once asked why Spartan swords were so short, to which he replied: “Because we fight close to the enemy!” Thus, the sword was most likely shortened in order to make it more convenient in the crush that arose during the clash of the two phalanxes. It is clear that in such a fight even a warrior, deprived of armor, but dexterous and evasive, could win. That is why in the 5th century. They completely abandoned armor, with the exception of shields and helmets, and attacked the enemy at a run! When the Spartan’s spear broke at the moment of collision, he struck them at the enemy’s head, and his short sword allowed him to deliver stabbing blows aimed at the face, thighs and stomach. Moreover, they became especially effective after the Greeks and other cities opposing the Spartans also began to abandon armor, leaving only shields and helmets for their warriors. That is, the training of all warriors acting together was, in their opinion, much more important than the skill of each individual!

Swords of the ancient Celts

The Celts are a warlike people who settled throughout Western Europe from southern Germany at the beginning of the 5th century. BC. - at first they also fought, standing on two-horse chariots and throwing darts at their enemies, but then, when they ran out of darts, they got off the chariots to the ground and challenged the bravest enemy to a single duel. At the same time, the Celtic warrior could burst into a barbaric song, glorifying himself and his ancestors and... also a stream of curses that insulted his enemy!

1. Central European sword of the Late Bronze Age, the so-called “antenna”, 850-650. BC. 2. Iron sword of the Hallstatt culture. Austria, 650-500 BC. The hilt is made of ivory and amber, decorated with gold foil 3. Iron sword of Greek hoplites, around the 4th century. BC. 4. Iron single-edged sword from Spain, V-VI centuries. BC. 5. Iron blade of a sword of the La Tène culture, around the 6th century. BC, Switzerland 6. Iron sword with a bronze hilt covered with enamel. Cumbria, England, 1st century. AD 7. Iron Roman short sword of legionaries - gladius, 1st century. AD 8. Late-type Roman gladius sword with parallel edges. Pompeii, end of the 1st century. AD

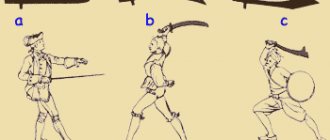

However, quite soon the Celts had four types of warriors: heavily armed infantrymen, whose main weapon was the sword, lightly armed infantrymen - throwers of darts (short light spears), cavalry riders and traditional chariot fighters. At the same time, according to the descriptions of ancient Roman historians, Celtic warriors in battle usually raised their swords above their heads and brought them down on the enemy from above as if they were chopping wood. Celtic swords are found in literally hundreds, so scientists have been able to study and classify them well. Since a number of such swords were discovered in the town of La Tène, the culture to which they were characteristic was called La Tène and even four phases were identified in it. La Tène swords had an average length of 55-75 cm, their cross-section resembled a rhombus, and the hilt was cast from bronze. It is interesting that they were worn not on the left, but on the right side, on an iron or copper chain. Only in the time of Caesar did the Celts’ swords begin to reach one meter or more in length, and their handles began to be decorated with enamel and even precious stones. But even with shorter swords they fought very skillfully and bravely. So it was very difficult for the same Romans to fight the Celts - especially if they fought with such long swords. Therefore, they had no choice but to develop appropriate weapons and... appropriate tactics for this!

The main methods of obtaining iron and steel

Since ancient times, the main method of producing iron was the so-called “cheese-furnace” process, when a large amount of ore, charcoal, and fluxes were loaded into an ore furnace (forge or blast furnace) and unheated (“raw”) air was blown in to maintain combustion. In this case, most of the iron left the ore along with the slag. A serious technological breakthrough in metallurgy occurred only at the beginning of the 16th century, with the discovery of a “direct” conversion process for producing high-quality steel from ore.

The traditional “iron-making” furnace was a truncated cone 1 to 2 meters high, with a base diameter of approximately 60-80 cm. The forge was built from refractory brick or stone, coated with clay on top, which was then fired. A pipe led into the furnace to supply air, which was pumped using bellows, and in the lower part of the furnace there was a hole for removing slag.

Homogeneity was imparted to the raw material by re-burning kritsa (cast iron) fractions into steel and processing the resulting iron and steel by forging. This process solved several problems at once:

- Cleaning iron and steel from excess impurities;

- Welding different layers of steel;

- Blade making;

- Heat treatment during finishing and hardening of the finished product.

To give steel the necessary properties, blacksmiths-gunsmiths saturated the alloy with carbon or, on the contrary, burned off its excess. The required heating temperature of the metal during all processes was calculated by the craftsmen solely by the color of its glow.

Shaped like a gladiolus leaf...

In response to the threat from the Celts, whom the Romans called Gauls, Rome created the most remarkable complex of weapons that had ever existed! Thus, legionnaires, that is, warriors fighting as part of the legion, were armed with a piercing-cutting sword “gladius hispaniensis”, i.e. "Gladius from Spain." The two earliest swords of this type were found in Slovenia, and they date back to around 175 BC. They have rather thin, diamond-shaped blades, which are indeed somewhat similar to a gladiolus leaf 62 and 66 cm long, and they are really convenient for chopping and stabbing. The second was the pilum throwing dart, which was intended primarily to pierce the shield of an enemy warrior and, if possible, wound him. At the same time, the long sleeve of its tip easily bent under the weight of the shaft, so it was impossible to either remove it from this shield or cut it off with a sword - and it turned out that the shield, along with the pilum stuck in it, had to be thrown!

A flint dagger that imitates the shape of early, pre-existing bronze daggers, suggesting that people always trust the old over the new. The meticulous finishing demonstrates the skill of its creator. Found in Sweden

But the most impressive Roman invention was the legionary shield - the scutum, which all “heavy” infantrymen had without exception! At first it had an oval shape, and later it turned into a curved rectangle, as if cut out of a huge pipe, about 70 cm wide and more than a meter high! It was made from wooden plates glued together lengthwise and crosswise, that is, from plywood, after which they were covered with leather, felt, and on top with fabric, the surface of which was usually brightly painted. The handle of such a shield was located horizontally, and on the outside the recess made for it was covered by a bulge specially attached to the shield - the umbon, which was wooden in early shields, and metal in later ones. In addition, the shield had metal padding along the top and bottom edges. The weight of such a shield reached 10 kg in the heaviest samples, and 7-8 in the light ones, so, in fact, it was a real “garden gate” with which a Roman warrior went into battle, being covered from head to toe . There was no longer any need to maneuver and somehow parry attacks with such a shield; here everything depended on the general tactics and training of the entire legion. The fact is that, when attacking the enemy, the Romans walked towards him in orderly rows, and on command they threw pilum darts, aiming at the shields of their opponents. Since it became impossible to use a shield with a pilum stuck in it, they had to throw them - and that’s when the Romans attacked them with swords in their hands!

Important project

Tell us about The Narrow Road project. What kind of film is this and what is its plot? Who's starring in it, who's directing it, and where can I watch it?

The Narrow Road is an ambitious film project currently in production. I have been collaborating with the project for the last 2 years. We are still in pre-production, so the film's release date is not yet known.

I work on the project as the lead artist, gunsmith, consultant and gunsmith technician, and graphic web designer.

The film is based on John Bunyan's classic book Pilgrim's Progress. This book was first published in 1678 (it greatly influenced authors such as Tolkien, Lewis, and Chesterton) and is considered the greatest allegorical work of all time.

The novel is considered an English classic, and for many generations it has sold millions of copies around the world and has been translated into dozens of languages. This epic work describes a pilgrim's journey in search of salvation from impending doom.

Christian, the main character of the book, a pilgrim, must overcome many obstacles on his way and meet a variety of characters - strange, unbridled and even evil - on the way to the beautiful Heavenly City.

This book is a wonderful allegory of the life of a believer, the struggle against sins, and salvation in God, who alone can give us deliverance from sins and suffering. She presents deep questions of theology in simple, accessible, yet powerful language. Readers who loved the book for its ideological message, simplicity and interesting adventures, I think, will accept and love this film, which follows the letter and spirit of Bunyan's novel.

Filming of “The Narrow Road” is underway

The film will use modern cinematography technology to set the action in a dream-like world like Bunyan's, and the art direction, while fantastical, will resemble a medieval world.

Stabbing is better than chopping!

Having run up properly, the legionnaire brought down both the weight of his body and the weight of the shield on the enemy and tried to overturn him to the ground. If he fell, he was finished off with a stabbing blow from the sword, and long swords were not required! In this case, stabbing was much more convenient than chopping! But if someone, in turn, tried to hit the legionnaire with his long sword, then... the metal edge of the scutum protected him from this!

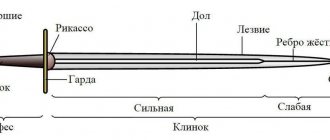

As for the Roman cavalry, the horseman's sword was slightly longer than that of the infantryman - after all, he had to cut from a horse - and it was called spatha. The design of both of them was almost the same: the blade was diamond-shaped, the handle (usually made of ivory) had cutouts for the fingers, and the massive “apple” of the pommel and guard were made of wood.

Roman infantry swords (gladius). Left - early version, right - late

By the end of the 1st century. BC. - beginning of the 1st century AD it was still a weapon with an elongated piercing point, 50-56 cm long and weighing about one kilogram. By the end of the century, swords began to be made of the same width along the entire length of the blade and with a shorter tip. Moreover, the swords of the horsemen also became exactly the same (their length was 60-70 cm), so calling them in the old fashioned way a gladius could only be due to tradition, but there was nothing left of the gladiolus leaf in them! It is interesting that the shields of the mounted warriors, as well as those of the allies of the Romans who served in the Roman army, were oval or octagonal and flat, in contrast to the traditional legionary scutum. Apparently, it was by them that these warriors were distinguished in the heat of battle!