The first and last battle of the cruiser "Blücher"

Blücher was the second heavy cruiser of the Admiral Hipper class. She was laid down in Hamburg on August 15, 1936 as a replacement for the cruiser Berlin. On June 8 of the following year, she was launched and named in honor of the Prussian field marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, the winner of Waterloo. However, the fate of the ship was not so successful. The vessel's entry into service was delayed due to changes constantly being made to its design. On September 20, 1939, Blücher was finally officially accepted into the Kriegsmarine under the command of Captain 1st Rank Heinrich Woldag. But it was still far from full combat readiness; all defects and malfunctions had to be corrected, which only happened on November 27, when the cruiser was sent for testing in the Gotenhafen area. But due to the fact that the winter of 1939−1940. It turned out to be harsh, the ship never passed comprehensive tests and a proper course of combat training. Despite this, in the spring of 1940 he was nevertheless included by the command in the operation to capture Oslo.

"Exercise on the Weser"

Germany managed to conclude a non-aggression pact with Denmark on May 31, 1939. The Germans made attempts to conclude similar agreements with Sweden and Norway, but they rejected these proposals, feeling their safety across the straits. Norway's neutrality did not suit either Germany or Great Britain, and both countries even made several provocations to provoke Oslo to abandon its position.

For the Germans, Norway was the key to the North Sea and a route for the transit of much-needed Swedish ore. On December 14, 1939, Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht command to study the possibility of capturing Norway. On January 27, a separate headquarters was created to develop the operation, which received the code name “Exercise on the Weser.” After the battle of the tanker Altmark with British destroyers in the neutral waters of Norway on February 16, the development of the plan was accelerated. Already on February 24, the headquarters under the leadership of General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst began a detailed study of the operation, and 5 days later the plan was presented to Hitler. It was planned to carry out a simultaneous lightning-fast landing of troops in key cities, preferably without the use of weapons. The directive of March 1, 1940 stated: “In principle, we must strive to give this operation the character of a friendly capture, the purpose of which is the armed defense of the neutrality of the northern states. Relevant demands will be submitted to governments once the takeover begins.” The Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine, Ehich Raeder, advised the operation to be carried out before the end of the polar night, that is, until April 7, but Hitler approved the ninth day as “Weser Day.” In addition to Norway, Denmark also came under attack, since the Germans needed to ensure the safe movement of maritime transport through the Danish straits, and in addition, Germany needed the airfields of Jutland to supply its landing forces.

Almost all the ships of the Reich's military and merchant fleets were used for the operation. Apparently, only the lack of ships for attack forced the German fleet to use the uncombatable Blucher. True, it was supposed to be used for simple tasks. He became part of the capture of Oslo under the command of Admiral Kümmetz, who transferred his headquarters to the cruiser. 830 troops boarded, including 200 staff members, including Generals Engelbrecht and Stussmann. The interior and even the deck were littered with landing ammunition and other fire hazards. The ship's overload worsened its already weak combat effectiveness. Military intelligence misled the Kriegsmarine due to a lack of intelligence about the forces of the Norwegian side, so the troops did not expect to encounter any serious resistance from the Scandinavians. German ships, according to the instructions of Admiral Kümmetz, could open fire only upon a signal from the flagship, not paying attention to warning salvoes and floodlights, which were recommended not to be shot, but to be blinded by oncoming combat lighting.

On the morning of April 7, 1940, the cruisers Blücher and Emden, accompanied by the destroyers Mewe and Albatross, left Swinemünde. In the Kiel area they linked up with the rest of the invasion group and were able to reach the Skagerrak undetected. In the evening they were spotted by two British submarines, Triton and Sunfish. The Triton was spotted by the Albatross and fired a salvo, but the Blucher managed to evade the fired torpedoes. Later, Sunfish also noticed a German detachment, which she reported to the British command, but did not attack. The detachment entered the Oslofjord without hindrance, and the expectation of surprise was justified. The Norwegian patrol ship Pol III opened warning fire on the Albatross, but failed to inflict any significant damage on it. The destroyer's crew boarded the Norwegian ship, during which Lieutenant Commander Leif Velding-Olsen, the first Norwegian to die in World War II, was killed.

Map of the Oslo Fjord

"Blücher" and the detachment had to pass between the islands of Bolerne and Rana. Searchlights flashed on the islands and a warning salvo was fired, but the Germans strictly followed the instructions and did not take any retaliatory action, calmly moving on. The Norwegians were a little surprised by such “friendliness” and therefore were late with fire from the coastal batteries - the shells fell behind the German column. The only thing the Norwegians managed to do was turn off the lights on the fairway, which forced the Germans to reduce their speed by almost half.

On April 8 at 00:45 Blucher gave the signal to land in the area of the Horten base. Part of the crew from it and the Emden was transferred to patrol boats and, accompanied by destroyers, sent to the shore. At about 5 am, the German ships approached the narrow passage of Drobak. To overcome this fortified area, the situation was not very favorable for the Germans: the landing force could not capture the coastal batteries and could open fire. Then Rear Admiral Kümmetz made an ambiguous decision - at the head of the column he decided to place the Blucher, which was quite weak by combat standards, and not the armored battleship Lützow. This decision looks even more controversial given the fact that Kümmetz knew about the Norwegians' mining of the fairway. Perhaps he was misled by intelligence data and hoped for a favorable and quick outcome.

At 5 a.m., fire was opened on the Blücher with 150 and 280 mm guns from the Kaholm and Kopaas batteries of the Norwegian fort Oxarsborg. Two shells from 280 mm guns hit the fire control post and the hangar on the left side of the cruiser, starting a fire and explosion of ammunition. About 20 shells of 150 mm guns reached the target and disabled the steering gear and communications with the engine room, the steering wheel jammed and the Blucher turned its nose toward the shore. Due to damage to the main artillery post, the Germans could not respond with targeted fire; in fact, they were forced to aimlessly fire in all directions from 105 mm cannons and anti-aircraft guns. After 20 minutes, the cruiser was hit twice by torpedoes from the port side, one hit the boiler room, the second hit the forward turbine room. All the lower rooms were filled with smoke. AC and DC networks are out of order. At 5:23 the Norwegians ceased fire. "Blücher" was engulfed in fire and rolled onto its left side with a list of 10 degrees. The ammunition with which the cruiser was filled kept catching fire and exploding, and the fires could not be contained. "Blücher" anchored east of the island "Askholmen". At about 6 a.m., a strong explosion occurred in the cellar of the seventh compartment, oil began to leak from the onboard oil compartments, and the smoke intensified. After the explosion, the ship's flooding became impossible to control, and the list increased to 45 degrees. Then Captain Voldag gave the order to abandon the ship. Despite the fact that the water was icy, many soldiers managed to swim to the shore.

At 7:23, the Blucher began to slowly go under the water with its nose down. Soon the cruiser reached the bottom at a depth of 70 meters. After the sinking, several underwater explosions were heard, and oil burned on the surface for several hours.

The cause of the death of the cruiser was a combination of various factors - from false German intelligence data to the insufficient combat readiness of the ship itself. The exact number of victims on the Blucher is still unknown. According to Germany, 125 crew members and 122 paratroopers were killed. 38 ship officers, 985 sailors and 538 army soldiers and officers were rescued.

How often do you visit norge.ru?

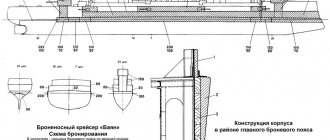

HISTORY OF CREATION

On July 6, 1935, Admiral Hipper was officially laid down at the Blom und Voss shipyard in Hamburg, and a month later construction began on Blücher. In April of the following year, the laying of the Prinz Eugen took place at the Krupp Germania shipyard. Two additional ships of a modified design were ordered in Bremen, where they were laid down in December 1936 and August 1937, respectively. The new class of cruisers received mostly “non-marine” names. Only the lead one was named after the commander of the German battlecruiser detachment at Dogger Bank and Jutland and the last commander of the High Seas Fleet, Admiral von Hipper. The other three were named after German land commanders, although the names Blücher, Seydlitz and Lützow were traditionally used in the German navy. The previous “generation” belonged to the most combative German ships: the armored cruiser Blücher died in the battle of Dogger Bank, Lützow sank after the Battle of Jutland, in which the Seydlitz almost sank. The name of the third ship in the series stands out. Prince Eugen is known to us as the famous Austrian commander Eugene of Savoy. The name was assigned for political reasons: thereby emphasizing that Austria, which became part of the Third Reich, is a full member of the “German Empire.” The slipway period for the construction of the lead ship of the “Admiral Hipper” series took a year and a half; for the remaining units it was about two years.

SERVICE HISTORY AND DEATH

The second cruiser of the series formally entered service on September 20, 1939, after numerous delays due to design changes during construction. However, after acceptance by the commission, the Blucher had not yet become a combat unit: all sorts of improvements and corrections continued for another month and a half. Only in mid-November was the commander, 47-year-old captain zur see Heinrich Foldag, able to begin preliminary tests of his ship while still at the pier. They discovered problems with the machines, and they had to spend the whole month in Kiel, “bringing” the cruiser to the point of being able to go to sea. Finally, on November 27, Blücher left the factory and headed to the Gotenhafen area, where it began final testing of the mechanical installation. Due to wartime, official test results were not recorded.

Upon completion of the test cruise, the cruiser returned to Kiel, where work on it continued. Only on January 7, 1940, Blucher was finally able to leave the plant. But it could by no means be considered a combat-ready ship, since even test artillery and torpedo firing was not carried out, not to mention exercises. The only safe place to conduct them was the eastern Baltic, where Blucher headed. The harsh winter of 1939/40 completely ruined the already inhospitable conditions of the Baltic Sea, which was inhospitable at this time of year. Snow and fog made it impossible to fire, and the ice that bound the water could only be broken by icebreakers, which were needed for other needs. I had to return to Kiel, where the cruiser arrived on January 17. For 10 days, the unfortunate ship was at a dead anchor in Kiel Bay, quickly freezing into the ice. There was no better solution than to move it back to the factory berth. Taking advantage of the opportunity, engineers and workers again began numerous small works that lasted until the end of March. As a result, the ship, which was formally in service for almost six months, left the outfitting wall for only 19 days and could not be considered a full-fledged combat unit.

However, the Naval Headquarters had very definite plans for him. The urgent need for ships for Operation Weserubung, in which the entire fleet was involved, forced the OKM to include Blücher in the lists of participants in the invasion of Norway. The decision, however, indicated that the cruiser was suitable for “simple tasks”, but did not specify what exactly was meant by this. He never fired a single shot from the main caliber guns; There were also no such important general exercises to eliminate the consequences of combat damage and fight for survivability.

Under such conditions, the headquarters of the naval commander of the group for the attack on the capital of Norway, Oslo, Rear Admiral Kümmetz, boarded the ship, and on April 5, the Blucher left for Swinemünde, the starting point of the operation. The loading of the cruiser began. It received approximately 830 Army personnel, of whom only 600 were combat troops of the 163rd Infantry Division. The rest were the headquarters of this division and the entire group of forces intended to capture southern Norway, under the leadership of Major Generals Engelbrecht and Stussmann, as well as numerous service units, including the personnel of the future radio station in Oslo. A fairly large amount of ammunition was also loaded onto the ship, and since there was still training ammunition in the cellars, and there was no time to unload it, it was necessary to fill all the regular storage facilities with live ammunition, charges and cartridges. There was simply no room for military explosive cargo under the armored deck and they had to be placed in the torpedo workshop and simply on the upper deck, behind the forward TA on the starboard side. Some of the cargo ended up in the hangar, where 200 kg of bombs and a reserve aircraft were stored (though not refueled). The third Arado had to be left on the shore - there was simply no room for it. As a result, the already not fully combat-ready Blucher found itself cluttered with fire-hazardous cargo and potentially already lost a significant part of its combat stability. All this took its toll very quickly.

Early on the morning of April 7, Blücher and Emden, accompanied by the destroyers Mewe and Albatross, left Swinemünde and soon linked up in the Kiel area with the rest of the southern invasion group. The column, led by Blücher, followed by Deutschland and the light cruiser Emdem and 3 destroyers, formed the main core of the Oslo battle group, which also included the 1st minesweeper flotilla (8 units) and 2 whalers. They were supposed to deliver about 2,000 landing troops of the first wave. The detachment only reached the Skagerrak undetected, when at 7 o'clock in the evening it was discovered and attacked by the English submarine "Triton", which in turn was spotted by the "Albatross" and fired a salvo from an awkward position. "Blücher" safely dodged the fired torpedoes. A little later, another English submarine, Sunfish, also observed the German formation, but was unable to attack, although it did a more important thing - it reported it to the command. However, the purpose of the German detachment one way or another remained a secret both for the British and for the target of the attack - the Norwegians. In the ensuing darkness, the column entered the Oslo Fjord, where all the navigation lights were burning. Suddenly the lead destroyer Albatross found itself in the spotlight. A small Norwegian patrol ship, Pol-Ill, a whaling steamer armed with light guns, opened warning fire. The order immediately came from the Blucher: “Capture the enemy!”, which was carried out by the destroyer.

Now the Blucher and other ships of the German detachment had to travel about 100 km along the fiord and overcome two fortified areas. Each of them included a battery of heavy artillery (280-305 mm) and several coastal batteries of smaller caliber. At first, the Germans needed to pass between the islands of Bolerne and Rana, which guarded the entrance to the fjord and the approaches to Norway's main naval base, Horten. The Norwegians did not sleep: as soon as the heavy cruiser came abeam the islands, searchlights illuminated it from both sides. Following this, a warning shot was fired, missing the target. And yet the battery commanders hesitated to make the most important decision - to open fire to kill. Maintaining a high speed for a cramped fairway (about 15 knots), the attacking detachment passed through narrow sectors of fire from the main battery before the doubts of the defenders dissipated. When the battery command came to its senses, the Oslo battle group had already passed the dangerous place. 7 shells fell 100-300 m behind the column. The only thing the Norwegians managed to do was turn off the lights on the fairway.

The Germans owe their first success, in addition to the passivity of the enemy, to the precise instructions of Admiral Kümmetz, who ordered to open fire only on a signal from the flagship, ignoring warning salvoes and not paying attention to the illumination of searchlights, which were recommended not to shoot at, but to blind the operators with their own combat lighting.

At a quarter to one on April 8, "Blücher" gave the signal to stop and begin landing in the area of the base in Horten. To do this, part of the troops from him and Emdem were transferred to 6 patrol boats of the “R” type (Raumboote) and, accompanied by the Albatross and Condor, were sent to the shore. The main detachment set off again, although Kümmetz was forced to give the order to reduce the speed to 7 knots - sailing at high speed in the absence of navigation lights became dangerous. Ahead of the Germans was a second fortified area, located in the narrowness of Drobak. At this point the Oslo Fjord narrows to about 500 m, stretching between the two islands of Kaholm (north and south) and the rocky right bank. There were 6 artillery batteries on the islands (a total of 3 280 mm and 9 57 mm guns), and in Drobak there were 3 batteries (3 150 mm, 2 57 mm and 2 40 mm guns).

There was no longer any need to count on surprise: in the hours that had passed since the discovery, the Norwegians managed to bring the coastal defenses to readiness, although very relative. The batteries did not have enough officers and gun personnel (according to some sources, there were only 7 people in the 280 mm battery). However, most importantly, the defenders no longer had to guess whether to open fire. Outdated installations made it possible to fire in very narrow sectors, and if they had to fire warning shots, it would hardly be possible to reload the guns.

Nominally, the main force was the three-gun Oscarborg battery on the island. Kaholm. The 280 mm Krupp model 1891 guns fired fairly light 240 kg shells, which, however, could prove fatal to any ship that was part of the German group. In the pre-dawn darkness, the Blucher managed to get out of the firing angle of one of the guns, which the Norwegians called by biblical names. But the other two, “Aaron” and “Moses,” managed to fire their shots at direct fire. At such a short distance (from 500 to 1500 m - according to various sources) it was impossible to miss.

At 5 am, the first shell hit the upper part of the tower-like superstructure in the area of the anti-aircraft artillery fire control post. The post itself was not damaged, but shrapnel caused heavy casualties among the personnel, including the 2nd Artillery officer, Lieutenant Commander Pohammer. The second 280-mm shell hit the left side hangar. The explosion destroyed both aircraft and a twin 105-mm anti-aircraft gun. A fire immediately broke out, the “food” for which were barrels of gasoline and boxes of ammunition for the landing force. But neither hit nor the other posed a significant danger to the cruiser. For a moment it seemed that he had succeeded in solving his problem - there were no further salvoes from Oscarborg: the Blucher left the firing range.

But then the 150-mm battery in Drobak came into play. Apparently, there were enough personnel to service three guns, and within 5-7 minutes the Norwegians managed to fire 25 shells from a distance of about half a kilometer, of which about two dozen hit the target. They caused more serious damage to the cruiser than large-caliber hits. One of the shells disabled the starboard rear anti-aircraft control tower and the middle 105-mm installation. This hit, combined with a 280-mm shell that hit the hangar, turned the middle part of the hull into a pile of burning debris. One of the first shots disabled the steering gear and communications with the engine room. The rudder jammed in the “left on board” position, and the cruiser turned its nose towards the shore. Foldag had to give the order to stop the right car and give full reverse to the left one in order to get past the island of North Kaholm as quickly as possible.

Immediately after the first hit, Foldag ordered the senior artillery officer, Corvette-Captain Engelmann, to open fire. But the main artillery post on the tower-like superstructure was immediately filled with thick smoke from the first hit, and fire control had to be transferred to the third artillery officer, who was in the forward command post. However, from this lower point, no clearly visible target could be detected in the morning haze. However, 105 mm cannons and light anti-aircraft artillery opened indiscriminate fire along the shore, which did not cause any harm to the defenders.

The crew was able to quickly establish a temporary connection with the vehicles through the central post and activate the emergency steering. No more than 8 minutes have passed since the first shot from Oscarborg. The cruiser was still moving at 15 knots, quickly leaving the firing sectors of the battery in Drobak and the 57-mm batteries on both banks. But at 52 a new surprise followed. The cruiser's hull was rocked by two underwater strikes. It seemed to the senior officer that the ship had been hit by mines; the navigator believed that the cruiser had run into an underwater rock. However, emergency parties immediately reported torpedo hits from the left side.

According to German intelligence, there was a minefield in the Drebak narrows, but the Norwegians refute this assumption. Indeed, after capturing the fortified area, the Germans discovered several dozen ready-to-use mines, but not a single evidence of their installation. Setting up a barrier in advance on a deep and narrow fairway would have severely limited navigation to the capital of the country, and the Norwegians simply could not manage to lay mines in 4-5 hours at night. It is most likely that the Blucher actually received two hits from a coastal torpedo battery on the island. Northern Kaholm.

This battery was located in a rock shelter capable of withstanding hits from heavy bombs and shells, and had three channels with rail tracks for releasing torpedoes. After the surrender of the garrison, the Germans found 6 “fish” fully prepared for shooting on special carts, with the help of which they could be reloaded into the canals in 5 minutes. Obviously, with such a system it was impossible to carry out any aiming, but at a firing distance of 200-300 m this was not required. Although it was never possible to find the “authors” of the successful salvo against the Blucher (which is not surprising given the subsequent 5-year occupation of the country), the version of torpedo hits can be considered the most likely

Norwegian batteries fired for only 2-3 minutes after the underwater explosions. The damaged cruiser was still moving and had a list of about 10 degrees to port. The commander gave the order to stop shooting, and silence fell in the Oslo Fjord. But critical moments came for Blucher in this silence. The ship finally passed the last barrier of defense, but its position became more and more threatening every minute.

The middle part of the hull turned into a continuous fire, in which shells and cartridges of the landing force continuously exploded. The fire completely interrupted communication between the bow and stern ends, limiting the operation of emergency parties on the upper deck. The ammunition placed in the torpedo workshop detonated, the entire left side below the bow 105-mm installation and the deck in the same area were opened. Thick smoke poured out from there and flames appeared. In general, shells and cartridges, both army shells, which were hastily stuffed into different places on the deck and upper premises during the landing, and ship shells (intended for emergency opening fire and therefore stored above), became the main factor hindering rescue efforts. Their fragments destroyed almost all the fire hoses and constantly threatened the team. Some of the ammunition was thrown overboard or transferred to the lower rooms, but the explosions of hand grenades heated by the fire every now and then forced the emergency teams to abandon their work. From the top of the tower-like superstructure, the survivors managed to move down only with the help of bunks and cables, since the ladders were completely destroyed. The chaos was increased by the containers for the smoke mixture, which were hit by German tracer bullets and shells and emitted thick, completely opaque smoke. The threat of an explosion from their own torpedoes forced a salvo to be fired from the starboard side, but the roll did not allow the same operation to be carried out on the opposite side.

However, the greatest threat was still underwater holes. Both torpedoes hit the central part of the ship: one hit the boiler room No. 1, the second hit the forward turbine room. The anti-torpedo protection served its purpose to some extent, limiting the initial flooding, but all the lower spaces between compartments V and VII (bow turbine rooms and boiler rooms 1 and 2) filled with smoke. The failure of turbogenerators with a non-reducing load led to the rapid failure of both networks - direct and alternating current. Both bow turbines, starboard and port, stopped after a few minutes, and after some time, the chief mechanic, Corvette-Captain Tannemann, reported that the central turbine would also have to be stopped soon. The commander decided to anchor the ship, since the message from the survivability control posts indicated that the right and left turbines could be started in about an hour. A group of sailors under the leadership of Corvetten-Captain Tsigan barely managed to drop the anchor on the starboard side, as the growing list, which reached 18 degrees, increasingly interfered with the work.

The commander still hoped to save his ship, now anchored with its stern to the shore at a distance of 300 m from the tiny island of Askholm, located two miles north of the Norwegian batteries. However, around 6°°, a strong explosion occurred in the 105-mm cellar in compartment VII between boiler rooms 1 and 2. A column of smoke and flame erupted from the middle of the hull, finally breaking the connection between bow and stern. During the explosion, the bulkheads between the boiler compartments were destroyed, and oil began to leak from the onboard oil compartments, adding thickness and blackness to the smoke of the fire. Boiler rooms 1 and 2, the forward turbine compartment, generator compartment No. 2 and compartment IV, which contained anti-aircraft ammunition magazines, were flooded. The chief turbine mechanic, Corvetten-Captain Grasser, ordered all engine rooms to be cleared and informed the commander that the cruiser would no longer be able to set in motion.

By this point it became clear that it would not be possible to save the ship. After the explosion of the cellar, the spread of water became uncontrollable, and the list began to rapidly increase. Foldag ordered Corvetten-Captain Zopfel to lower the starboard boat, the only lifeboat that could be used. The seriously wounded were loaded onto it. The port side boat turned out to be broken, and there was nothing to lower the light boats with, since the aircraft cranes designed for this failed at the very beginning of the battle.

Although the Blücher was very close to land, rescuing everyone on board proved difficult. The enormously bloated crew was supplemented by a large number of troops: in total, according to various estimates, there were from 2000 to 2200 people on board. There were only enough life jackets for 800; in this case, the reception of an additional number of them could, in the opinion of the naval leadership, violate the strict secrecy of the operation. At the same time, part of this amount was burned as a result of a fire in the central part of the ship. The boat was able to make only one trip, and on the second it ran into a rock and was unable to return to the ship. Meanwhile, at about 7 o'clock in the morning, an hour and a half after the first shot, the list reached 45 degrees and Foldag gave the order to abandon the ship. Around 730, the Blucher turned over and began to slowly go under the water, nose first. Soon only the stern remained on the surface, and then it disappeared too - the cruiser reached the bottom at a depth of 70 meters. After the dive, several underwater explosions were heard, and oil continued to burn on the surface for several hours.

The exact number of victims on the Blucher remains unknown to this day. There are several “accurate” figures: German sources, in particular, indicate 125 dead crew members and 122 landing participants. It was possible to save 38 ship officers, 985 sailors and 538 soldiers and army officers. However, most reports about the death of the Blucher do not provide exact figures; usually these are "heavy" or "very heavy" losses, and the British official history of the war at sea states that the cruiser was lost with almost all of her crew and troops on board. That this is not so is obvious from the fact that both major generals and almost all the ship’s officers, including its commander, reached the shore. However, a year and a half later, an investigation into the circumstances of the loss of Blucher took place, inspired by army circles. The military blamed the sailors for the lack of life-saving equipment, the lack of instructions to the troops on what to do in the event of a possible sinking of the ship, and the commander for wrong actions, in particular for not throwing the ship ashore. In their opinion, all this led to “great losses” among the troops. Captain zur See Foldag could no longer answer these accusations. The death of the ship had a hard effect on him; on Askenholm he wanted to put a bullet in his forehead, from which General Engelbrecht had difficulty dissuading him. However, fate found Foldag: on April 16, the plane on which he was flying as a passenger crashed into the waters of Oslofiord, and the commander found his grave in the same place where his cruiser died.

The results of the investigation did not clarify much. The sailors testified that the accusations were unfounded and that the sailors voluntarily gave the few life jackets to the soldiers. There was neither the means (the cruiser had completely lost energy) nor the space to throw the ship ashore. The shores of the islands of the Oslo Fjord are so steep and quickly go into depth that there was simply nowhere to tuck the 200-meter hull.

The question may arise why one of the German ships famous for its survivability sank so quickly from not too serious damage. Several factors contributed to the death of the Blucher. The first of them is that the cruiser still received a very significant “dose”: up to two dozen shells and 2 torpedoes, and the crisis occurred as a result of increased flooding from torpedo hits due to the impact of shells (a fire in the anti-aircraft ammunition magazine). The second important factor is the cruiser’s insufficient combat and technical readiness. "Blücher" urgently set out on its first sea voyage without sufficient training of the emergency parties, the work of which was hampered by the presence of a large number of people and flammable cargo that were strangers to the ship. All this reduced the usually very high efficiency of rescue operations in the German fleet. The Norwegian-made 450-mm torpedoes themselves (or, according to some sources, Whitehead models from the beginning of the century) had a charge of 150-180 kg and corresponded in this parameter to the air torpedoes of Japan, England, the USA and Germany. As a rule, two hits were enough to completely disable, and in some cases, destroy ships of the cruiser class.

Published: BNIC/Shpilkin S.V. Source: kriegsmarine.ru

Heavy cruiser "BLÜCHER"

| Type | Heavy cruiser |

| State | Germany |

| Commissioned | September 20, 1939 |

| Current status | Sank April 9, 1940 |

| OPTIONS | |

| Tonnage | 16,974 t. - standard 19,042 t. - full |

| Length | 207.8 m - total. |

| Width | 21.5 m |

| Draft | 7.2 m |

| TECHNICAL DATA | |

| Power point | 3 propellers, turbines and 12 boilers with a total capacity of 132,000 hp. |

| Speed | 32.5 knots |

| Sailing autonomy | 6,100 nautical miles at 15 knots |

| Crew | 1600 officers and sailors |

| WEAPONS | |

| Artillery | 8 x 203 mm 12 x 105 mm 8 x 20 mm 4 x 533 mm torpedo tubes, 3 tubes each |

| Aviation | 3 seaplanes |

German cruiser Blücher

Launch of Blucher

in Kiel, June 8, 1937

Blucher

was ordered

by the Kriegsmarine

from the

Deutsche Werke

in Kiel.

[4] Her keel was laid down on 15 August 1936 [9] under construction number 246. [4] The ship was launched on 8 June 1937 and was completed just over two years later on 20 September 1939, the day she was launched. introduced into the German fleet. [10] Commander Admiral Marinestation der Ostsee

(Baltic Naval Base), Admiral Konrad Albrecht, gave the baptismal speech.

The baptism was performed by Mrs. Erdmann, widow of Fregattenkapitän

(frigate captain) Alexander Erdmann, former commander of the SMS Blücher, who died when the ship sank. [11] As built, the ship had a straight stem, although after her launch this was replaced with a clipper bow increasing the overall length to 205.90 m (675.5 ft). [3] A funnel cap was also installed. [12]

Blucher

spent most of November 1939 on equipment and modifications. By the end of the month the ship was ready for sea trials; she sailed to Gotenhafen in the Baltic Sea. [13] Tests lasted until mid-December, after which the ship returned to Kiel for final modifications. In January 1940, he resumed exercises in the Baltic, but by the middle of the month, due to heavy ice, the ship remained in port. On 5 April he was deemed ready for action and was therefore transferred to the troops participating in the invasion of Norway. [14]

Operation Weserübung

Blücher

on her way

to Norway, as seen from the light cruiser Emden

April 5, 1940 Rear Admiral

(Rear Admiral) Oskar Kummetz boarded the ship while it was in Swinemünde.

A detachment of ground forces from the 163rd Infantry Division, numbering 800 people, also boarded the ship. Three days later, on April 8, Blücher

left port for Norway; she was the flagship of the force that was to capture Oslo, the capital of Norway, by Group 5 of the invasion force [15]. She was accompanied by the heavy cruiser Lützow, the light cruiser Emden and several small escorts. The British submarine Triton spotted the convoy sailing through the Kattegat and Skagerrak, and fired a number of torpedoes; However, the Germans dodged the torpedoes and continued the mission. [14]

By the time the German flotilla reached the approaches to the Oslofjord, night had already fallen. Shortly after 23:00 (Norwegian time), the Norwegian patrol boat Pol III spotted the flotilla. German torpedo boat Albatros attacked Pol III

and set it on fire, but not before a Norwegian patrol boat raised the alarm, radioing an attack by unknown warships.

[16] At 23:30 (Norwegian time), the south battery on Rahway spotted the flotilla under a searchlight and fired two warning shots. [17] Five minutes later, Rahway Battery's guns fired four rounds at the approaching Germans, but visibility was poor and there were no hits. [17] The guns at Bolarne fired only one warning shot at 23:32. Before Blücher

could be aimed again, she was out of range of these coastal guns, and after 23:35 they saw her no more. [18]

The German flotilla was moving at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). [19] Shortly after midnight (Norwegian time), the commanding admiral's order to extinguish all beacons and navigation lights was transmitted over NRK ( Norsk rikskringkasting

) [Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation].

[20] German ships were ordered to open fire only if they were fired upon first. [14] Between 00:30 and 02:00 the flotilla stopped and 150 landing infantry were transferred to escort R17

and

R21

(from

Emden

) and

R18

and

R19

(from

Blücher

). [21]

Battle of Drobak Strait

One of three 28 cm (11 in) guns at Oscarsborg Fortress

The R-boats were ordered to attack Rahway, Bolarn, the naval port and the town of Horten. [21] Despite the obvious loss of surprise, Blücher

moved further into the fjord in order to reach Oslo by dawn on schedule.

At 04:20, Norwegian searchlights illuminated the ship again, and at 04:21, the 28 cm guns of Fortress Oscarsborg opened fire on Blücher

at very close range, beginning the Battle of Drobak Strait with two hits on the port side.

[14] The first was high above the bridge, hitting the battle station for the anti-aircraft gun commander. The main range finder at the top of the combat mast was knocked out, but Blücher

had four other main range finders. The second 28-centimeter shell hit near the aircraft hangar and caused a large fire. As the fire spread, he detonated explosives carried by the infantry, preventing the fire from being extinguished. As a result of the explosion, two people on board the Arado seaplane were set on fire: one on the catapult, and the other in one of the hangars. The explosion also likely blew a hole in the armored deck above Engine Room 1. Turbine 1 and Generator Room 3 stopped due to lack of steam, and only the suspension shafts from Engine Room 2/3 were operational. [22]

The Germans were unable to detect the source of the fire. Blucher

increased speed to 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) in an attempt to outflank the Norwegian guns.

[14] The 15 cm (5.9 in) guns on Dröbak, about 400 yards (370 m) on Blücher

's starboard side, opened fire as well.

[23] At a distance of 500 m (1,600 ft), Blücher

entered the narrow zone between Kopos and Hovedbatteriet, the main battery, at Kaholmen.

Kopas's battery ceased fire on Blücher

and hit the next target,

Lützow

, with many hits.

[24] First Engineer Karl Tannemann wrote in his report that all hits from the guns on Drøbak that were fired from the starboard side occurred between sections IV and X at a length of 75 m (246 ft) amidships, between the B-turret and C -turret. However, all the damage was inflicted on the port side. [25] After the first salvo of 15 cm batteries at Drøbak, steering control from the bridge was disabled. Blücher

had just passed Drøbackgrunnen (Drøbak Banks) and was turning to port. The commander returned her to the right direction by using side shafts, but she lost speed. [26] At 04:34, two torpedoes from a hidden and unknown battery near Oscarsborg Fortress hit the ship. [23]

Blucher

on fire and sinking in the Drobak Strait

According to Kummetz's report, the first torpedo hit boiler room 2, directly below the funnel, and the second hit turbine room 2/3 (the turbine compartment for the side shafts). Boiler No. 1 had already been destroyed by firearms. Only one boiler remained, but the steam lines through boilers 1 and 2 and turbine room 2/3 were damaged and turbine 1 lost power. [26] By 04:34 the ship was seriously damaged, but successfully passed the fire zone; most of the Norwegian guns could no longer fire at her. All of the 15 cm guns of the Copas battery were in open positions with a wide range of fire and were still within range. The battery brigades requested orders, but the fortress commander, Birger Eriksen, concluded: “The fortress has fulfilled its purpose.” [27]

Having passed the artillery batteries, the crew, including the personnel of the guns, were given the task of extinguishing the fire. By then she was on the list of 18 degrees, although this was not initially a problem. The fire eventually reached one of the ship's 10.5 cm magazines between Turbine Hall 1 and Turbine Room 2/3, which exploded violently. As a result of the explosion, several bulkheads in the engine room were damaged and the ship's fuel storage facilities caught fire. The battered ship began to slowly capsize and the order was given to abandon ship. [28] Blucher

capsized and sank at 07:30 with significant losses. [29] Naval historian Erich Gröner states that the number of casualties is unknown, [10] and Henrik Lunde puts the casualty figure at between 600 and 1,000 soldiers and sailors. [19] Jürgen Rover, meanwhile, states that 125 sailors and 195 soldiers died in the sinking. [thirty]

Loss of Blucher

and the damage inflicted

on Lützow

forced the German forces to retreat.

Ground forces landed on the eastern side of the fjord; they proceeded inland and captured the Oscarborg fortress by 09:00 on 10 April. They then moved to attack the capital. Airborne troops captured Fornebu airport and completed the encirclement of the city, and by 14:00 on April 10 it was in German hands. The delay was caused by the temporary withdrawal Blücher

's task force, however, allowing the Norwegian government and royal family to flee the city. [19]

New in blogs

On April 9, 1940, in the Oslofjord, the German heavy cruiser Blucher with troops on board was sunk by the garrison of the Oscarsborg fortress.

This detachment of German ships entered the Oslofjord to land troops and capture the capital of Norway. We will talk about the events preceding this battle, about the Government of Norway and its fantastic illusions, and about the Norwegian military who fulfilled their duty in this article. Operation Weserubung

Even at the stage of preparation for World War II, Nazi Germany faced the question of resources. Since World War I, Germany has purchased Swedish iron ore. Its concentration from the Kirune deposit in Northern Sweden reached 65%. As of the early 40s of the twentieth century, this ore was considered the most concentrated in the world. German industrialists and the military greatly appreciated the opportunity to use this ore. Annual imports to Germany reached 10 million tons at the end of the 1930s. The issue with Sweden was resolved. The Scandinavian kingdom had long-standing friendly relations with Germany. And, apparently, the Nazis had guarantees of uninterrupted supplies. The issue was the delivery of ore to Germany.

In the summer, ore from the deposit was delivered to the Swedish port of Luleå in the Gulf of Bothnia. From there, ore was transported on cargo ships to German ports. This route was the most reliable, since in case of war it passed through Swedish territorial waters, which ensured uninterrupted supplies. However, this route had one significant drawback. In winter, the Gulf of Bothnia froze, and the number of Swedish icebreakers in the late 1930s was not enough to support regular voyages of iron ore ships. Therefore, in winter, ore was transported by rail to the Norwegian port of Narvik, and from there it was delivered by ship to German ports. For peacetime, the route was safe and relatively reliable. But in the event of the outbreak of war, this route was easily interrupted. The German General Staff made a fundamental decision to capture Norway. It is interesting that in the initial period the Germans were not particularly interested in the capabilities of Norwegian ports in terms of access to the Atlantic. Their main task was to ensure uninterrupted delivery of ore from Narvik. The British also understood this and began to develop similar plans. A race against time began, in which the main prize was the fate of an independent state.

The situation was heating up. The trigger was events called the “Altmark incident.” Its essence was as follows. The Altmark was a large Kriegsmarine tanker that supplied fuel to German raiders in the Atlantic. After another supply operation, the Altmark, with more than three hundred captured English sailors transferred from the “pocket” battleship” - the heavy cruiser “Admiral Graf Spee” in the South Atlantic to a tanker, entered the territorial waters of Norway, believing that he was in security. However, the British made a different decision. The leader of the destroyers "Kossak" - "Kozak" made a daring raid into Norwegian territorial waters and captured a German tanker with captured English sailors. The Norwegian navy observed the incident but did not intervene. When Hitler was informed of the capture, he was furious. It was after this incident that he decided to capture Norway. The essence of the German plan was as follows. The Germans understood that the superiority of the British on the high seas was certainly undeniable, so the only chance of success was to capture all the main ports of Norway in several detachments before the deployment of the English fleet.

As the media learned, several hundred residents of Yekaterinburg will be left without gas for a month due to the World Cup. The problem affected 14 houses.

Germany's plan was to take over Denmark and Norway. By and large, the Germans did not really need Denmark. It’s just that when Norway is captured, if Denmark is not captured, it becomes the springboard from which Great Britain can strike at any strategic direction in Germany itself.

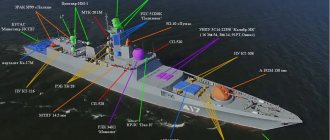

It was necessary to transfer eight divisions - two to Denmark, six to Norway. The Kriegsmarine was responsible for the naval part. Almost the entire German navy was involved - about 100 warships and boats, including two battle cruisers, 7 heavy and light cruisers and 14 destroyers and destroyers. The flagships of the capture squads were the battlecruisers Scharnhost and Gneisenau. About 50 requisitioned merchant ships from different countries were used to transport the landing forces. The Luftwaffe allocated 500 combat and transport aircraft for the operation. The main goal, the city and port of Narvik, was to be captured by 10 destroyers with two thousand paratroopers - Alpine riflemen from the 3rd Mountain Division. The Nazis also had a second, no less important goal - the capital of Norway, Oslo. It was to be taken by a cruising squadron consisting of the heavy cruiser Blücher, the light cruiser Emden, three destroyers Möwe, Albatross and Condor and 8 minesweeper boats of type R.

The British were also preparing to capture Norway. The Navy allocated 5 battleships and battlecruisers, 1 aircraft carrier, 13 heavy and light cruisers, 60 destroyers and 24 submarines for this operation. Germany had only one chance - to capture Norway first.

Norway. Government

Norway's history as an independent country is very unusual. After the union with Sweden was broken in 1905, the country gained independence. During World War I, Norway was a neutral country under strong pressure from Great Britain. It got to the point that the British bought 11 million pounds sterling - a huge amount at that time - all export fish so that Norway would not sell it to the Kaiser's Germany. After the end of the First World War, the three northern kingdoms of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark initiated the creation of the League of Nations - the first international organization, the predecessor of the United Nations. Historians of the 20th century undeservedly keep silent about the League of Nations, but in vain. This organization included almost all independent countries at that time, even the Soviet Union, which during the interwar period was not allowed to join any interstate association. On the one hand, the League was engaged in a “talking shop”, on the other hand, the first international treaties on the limitation of arms - specifically, naval weapons - the Washington Treaty of 1922 and its extension - the London Treaty of 1930 - were the result of the work of the League of Nations.

Norway participated very actively in international meetings, as they would say today, on issues of international security. The famous polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen was Norway's representative in the League. It was at his instigation that the so-called “Nansen passports” began to be recognized in the world, which were issued to refugees and gave them the opportunity to live and move between countries without having citizenship of a particular country. The Workers' Party, which came to power, carried out active anti-war propaganda. Military expenditures of all branches of the country's troops were reduced. Wanting to set an example, in the 1920s Norway reduced its already small armed forces. The issue of complete disarmament of the country and the transition to symbolic “neutrality protection forces” was discussed in all seriousness. This policy looked very strange in the thirties of the twentieth century, when it seemed that the entire air in Europe was saturated with the expectation of an impending military catastrophe.

In 1936 alone, parliament allocated an additional 4 million crowns for a number of military programs. But it was a symbolic gesture. In 1940, after Hitler the decision to seize Norway, Norwegian generals and admirals went to the local parliament as if at work, asking the leadership of the country and parliament to announce a mobilization order. In vain. Meanwhile, the Swedish consul Karl Wendel and naval chaplain Hulgthard , on instructions from the Swedish ambassador to Germany Richert , using his diplomatic immunity, visited the German port of Stettin. Diplomats, taking risks, conducted a reconnaissance of the port and talked with the crews of the Swedish ships that were in the port. They discovered dozens of transport ships on which troops were boarded. It will become clear later that the Germans deployed about 50 transports. And then the bold foray of Swedish diplomats revealed Germany’s preparations for a large landing operation. The Swedes did not keep the information they received secret, and the Swedish ambassador to Germany contacted the Norwegian ambassador Arne Scheel . At the same time, the Swedes sent a copy of the report from the Swedish consul to the Norwegian Foreign Ministry in Oslo. But the Norwegian Ambassador to Germany, Scheel, did not see any threat to his country in the Swedes’ story, which he reported to the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kut . The minister did not inform anyone about the ambassador's report or the Swedes' letter.

It reached the point of grotesquery. German officers who did not agree with plans to occupy Norway informed the Norwegians about Hitler's plans for their country. They conveyed this information through the Dutch military attaché in Germany. The Dutch, as they say, carried out a wide distribution of the information received to Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo. But Norwegian Foreign Minister Kut shelved this report too. It would be funny if it weren't so sad. The Prime Minister of Norway calls the President of the Storting - Parliament - and asks if he has any information from the Minister of Foreign Affairs. In the Government, Kut refused to communicate about the possible threat of a German invasion...

Norway. Armed forces

The army of this Scandinavian kingdom was indeed small. There were few ground forces, very few aviation, there were about two dozen tanks and armored vehicles. Norway had two components that made it possible not to surrender the country immediately, but to hold out for several days and wait for help from Great Britain - a small but balanced navy and Coastal Artillery - that’s what coastal fortresses, batteries and forts were called in those years. Perhaps it was the Coastal Artillery that was the only force capable of delaying the German landing.

The fact is that the specifics of Norway are such that with a long coastline, landing troops can only be done at several points on the coast. These are the main large cities of the country - Oslo, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, Bodo, Narvik. These cities and ports were fairly well covered by coastal batteries, controlled by minefields and coastal torpedo batteries. The weak point of the coastal artillery was its personnel. There was a shortage of artillery soldiers; they were called up from the reserves and were not trained to fire large-caliber guns. The second drawback was that some of the guns were quite old, and there were almost no anti-aircraft guns anywhere that were supposed to cover the main batteries.

fragment of Oscarsborg fortress

Oscarsborg Fortress. The battle

Oslo, as the capital, was covered more reliably than other cities. The length of the Oslofjord is 102 kilometers. The outer part in the area of the Danish Straits. Patrol ships mobilized from whalers and fishing trawlers patrolled. A little to the north, closer to Oslo, there were several new coastal batteries and searchlight installations built in the 30s. The batteries were armed with Swedish 150 mm Bofors cannons. The third, and most important, line of defense was the Oscarsborg fortress. It was called the castle to Oslo. The fortress was located on an island in the middle of the Oslofjord. On one side, the shore of the fjord was connected to the island by an artificial dam. On the other, where the shipping fairway passed, there was a controlled minefield and several batteries on the other side of the fjord. The fortress itself was armed with three 280-mm guns manufactured by Krupa. They were made before the First World War and had their own names - “Moses”, “Aaron” and “Yeshua”.

280 mm Oscarsborg Fortress gun

Despite the fact that the guns were old, the shells for them were quite modern. But the most important trump card of the fortress, as it later turned out, lay elsewhere. The Germans very carefully carried out reconnaissance of the Norwegian coastal defenses. But they did not know about the underground torpedo battery of the Oscarsborg fortress. On the territory of the fortress, a shaft was cut down into the water to a depth of 3 meters, in which three guides for torpedoes were mounted. After the engines started, the torpedoes came out from under the rock. There was no chance to get past the fortress. The Oscarsborg fortress was commanded by Colonel Birger Eriksen .

Colonel Birger Eriksen

On the evening of February 21, a large-scale accident occurred on a heating main in the Vyborg district of St. Petersburg. As a result of the incident, residents of several multi-storey buildings on Prosveshcheniya Avenue and Simonov Street were left without heating.

But there were also weak points in the defense of the Oslofjord. So, some patrol ships, former trawlers and tugs did not have a radio, and to transmit information about a breakthrough, they had to approach one of the batteries and transmit information using a semaphore. On April 7, 1940, German Detachment 5 left Swinemünde. The detachment included the heavy cruisers Lutzev and Blucher, the light cruiser Emden, three destroyers and minesweepers. After some time, the detachment entered the Danish Straits and into the Oslo Fjord. Complete confusion reigned in the corridors of power in Oslo; information there was received from Norwegian Radio broadcasts. No order was received to Oscarsborg to put the minefields on alert. True, an order was given to turn off all lighthouses on the coast, which somewhat complicated the position of the German navigators on the invasion ships.

The first episode of the war was the sinking of the Norwegian patrol ship Pol III. This was a mobilized armed whaler who was on the patrol line furthest from Oslo. After discovering the Germans, the whaler's commander, Olsen , without a moment's hesitation, gave the order to intercept and open fire from a small-caliber cannon. The destroyer Albatross was assigned to deal with the obstinate patrol ship. Alas, the miracle did not happen. Pol III was sunk and its commander was killed.

The British recorded the passage of 50 transport ships and warships and reported this to the Norwegians. The Norwegian fleet remained completely silent. The second to collide with the German detachment was the Norwegian tugboat Furu. This was the same case when the tug did not have a radio station, and he was forced to approach one of the coastal batteries and signal in Morse code: “7 foreign warships have passed Filtvedt and are moving on. People on the ut speak German." Colonel Eriksen did not receive any commands from Oslo. When asked by his subordinates about his actions, he replied: “Shoot to hell!” The German detachment passed almost all the Norwegian batteries. Only one of them fired on German ships. This first fire contact took place at night, in the dark.

The sinking of the cruiser Blücher in the Oslofjord

As the Blücher approached Oscarsborg, it began to get light. Eriksen gave the order to open fire from the fortress's 280 mm guns. The distance was about 1,400 meters, it was impossible to miss. After the shot, the cruiser, engulfed in fire, slowly passed by the fortress. The big guns did not fire as the torpedo tubes of the underground torpedo batteries prepared to fire. Two fired torpedoes completed the rout. The newest German heavy cruiser of the Kriegsmarine capsized and sank. 1,600 crew members and 830 landing soldiers found themselves in the icy waters of the fjord. There is no exact data on the dead. According to German data, 125 crew members and 122 paratroopers were killed. The rest with frostbite reached the shore of the fjord.

The Germans issued an ultimatum to the Norwegian leadership, Luftwaffe planes bombed Oscarsborg. There was no air defense in the fortress. What happened next, how Germany completely captured Norway, and why Great Britain could not prevent this is a topic for a separate article.

Oscarsborg today

Conclusion

After the war, in 1945, the command of the Norwegian Navy awarded Colonel Eriksen and the commander of the torpedo battery of the Oscarsborg fortress Anderosen with the highest military award - the Military Cross with Swords. It was emphasized that those few hours gained after the sinking of the Blucher gave the opportunity to the royal family and the Norwegian government to leave the country. But the politicians who led the country to disaster did not forgive the colonel, who had fulfilled his duty. In 1946, a commission began working to examine the events of 1940. Eriksen was accused of all mortal sins. But since he was awarded the country’s highest military order for the same events, all charges were upheld, and further actions against Eriksen were stopped. He died in 1958 at the age of 82. In 1975, a monument was erected to Colonel Eriksen using private donations. In 1977, the urn containing the ashes was moved to the memorial cemetery in Oslo.

Source: https://versia.ru/garnizon-kreposti-potopil-korabl-s-desantom-bez-prikaza-iz-oslo

SMS Blucher

SMS Blucher

pre-war period, around 1913–1914

Blucher

was launched on April 11, 1908 and commissioned on October 1, 1909.

Since 1911, she served as a training ship for naval gunners. In 1914 she was transferred to I Scouting Group along with the newer battlecruisers Von der Tann

, Moltke and the flagship Seydlitz.

[9] The first operation in which Blücher

was an unsuccessful invasion of the Baltic Sea against Russian forces.

On 3 September 1914, Blücher,

along with seven dreadnought battleships of IV Squadron, five cruisers and 24 destroyers, sailed into the Baltic Sea in an attempt to remove part of the Russian fleet and destroy it.

The light cruiser Augsburg encountered the armored cruisers Bayan and Pallada north of the island of Dagö (now Hiiumaa). The German cruiser attempted to lure the Russian ships back towards Blücher

to destroy them, but the Russians refused to take the bait and instead retreated to the Gulf of Finland. On September 9, the operation was abandoned without any serious engagement between the two fleets. [17]

2 November 1914 Blücher

Together with the battlecruisers

Moltke

,

Von der Tann

and

Seydlitz,

accompanied by four light cruisers, he left Jade Bay and headed for the English coast.

[18] The flotilla arrived from Great Yarmouth at dawn the next day and bombarded the port while the light cruiser Stralsund laid a minefield. The British submarine HMS D5 responded to the attack, but struck one of the mines laid by Stralsund

and sank. Soon after, Hipper ordered his ships to return to German waters. En route, thick fog covered the Heligoland Bight, so the ships were ordered to stop until visibility improved and they could navigate the defensive minefields safely. The armored cruiser York made a navigation error that led her into one of the German minefields. She hit two mines and quickly sank; Only 127 of the 629 crew were rescued. [18]

Bombing of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

Blucher

during the First World War

Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, commander of the German High Seas Fleet, decided that another raid should be launched on the English coast in the hope of luring part of the Grand Fleet into battle, where it could be destroyed. [18] At 03:20 Central European Time on December 15, 1914, Blücher

,

Moltke

,

Von der Tann

, the new battlecruisers Derfflinger and

Seydlitz

, as well as the light cruisers

Kolberg

,

Strassburg

,

Stralsund

,

Graudenz

and two squadrons of torpedo boats left. Jade Estuary. [19] The ships sailed north past the island of Heligoland until they reached Horns Reef Lighthouse, at which point they turned west towards Scarborough. Twelve hours after Hipper left the Jade, the High Seas Fleet, consisting of 14 dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts, plus a screen of two armored cruisers, seven light cruisers and 54 torpedo boats, set out to provide remote cover for the bombardment force. [19]

On 26 August 1914, the German light cruiser Magdeburg ran aground in the Gulf of Finland; the wreck was captured by the Russian navy, which discovered code books used by the German navy, as well as navigation charts for the North Sea. These documents were then handed over to the Royal Navy. Room 40 began deciphering German signals, and on December 14, intercepted messages relating to the Scarborough bombing plan. [19] The exact details of the plan were unknown, and it was assumed that the High Seas Fleet would remain safe in port as during the previous bombardment. Vice Admiral Beatty's four battlecruisers, supported by the 3rd Squadron and the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, along with the six dreadnoughts of the 2nd Battle Squadron, were to ambush the Hipper's battlecruisers. [20]

On the night of 15–16 December, the main forces of the High Seas Fleet collided with British destroyers. Fearing a night torpedo attack, Admiral Ingenohl ordered the ships to retreat. [20] Hipper was unaware of Ingenohl's change in position and therefore continued the bombardment. Upon reaching the British coast, the Hipper battlecruisers split into two groups. Seydlitz

,

Moltke

and

Blücher

went north to bombard Hartlepool, while

Von der Tann

and

Derfflinger

went south to bombard Scarborough and Whitby.

Of the three towns, only Hartlepool was defended by coastal artillery batteries. [21] During the bombardment of Hartlepool Seydlitz

was hit three times and

Blücher

was hit six times by a shore battery.

Blücher

suffered minimal damage, but nine people were killed and three more were wounded. [21] By 09:45 on the 16th, the two groups had reassembled and began to retreat east. [22]

Disposition of the High Seas Fleet on the morning of December 16th.

By this time, Beatty's battlecruisers were able to block Hipper's chosen escape route while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group began to pass through the British forces in search of Hipper. [23] One of the cruisers of the 2nd light cruiser squadron spotted Stralsund

and signaled to Beatty. At 12:30 Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty suggested that the German cruisers were a forward screen for Hipper's ships, but the battlecruisers were some 50 km (27 mi; 31 mi) ahead. [23] The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been checking Beatty's ships, separated to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their checking positions. [e] This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to escape and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers turned northeast of the British forces and managed to escape. [23]

Both the British and Germans were frustrated that they were unable to effectively engage their opponents. Admiral Ingenol's reputation suffered greatly due to his timidity. Captain Moltke

was furious; he stated that Ingenohl turned back "because he was afraid of eleven British destroyers that could be destroyed... We will achieve nothing under the present leadership." [24] Official German history criticized Ingenohl for failing to use his light forces to determine the size of the British fleet, stating: "He made a decision which not only seriously endangered his forward force off the English coast, but also deprived the Germans . The fleet is a signal and a sure victory.” [24]

Battle of Dogger Bank

Blucher in

process

In early January 1915, the German naval command discovered that British ships were conducting reconnaissance in the Dogger Bank area. Admiral Ingenohl was initially reluctant to attempt to destroy this force because I Reconnaissance Group was temporarily weakened while Von der Tann

was in dry dock for periodic maintenance.

Konteradmiral

(Rear Admiral) Richard Eckermann - Chief of Staff of the High Seas Fleet - insisted on the operation, and so Ingenohl relented and ordered Hipper to withdraw his battlecruisers to Dogger Bank. [25]

On January 23, “Hipper” went on a campaign, led by Seydlitz

, followed by

Moltke

,

Derfflinger

and

Blücher

, as well as the light cruisers

Graudenz

,

Rostock

,

Stralsund

and

Kolberg

and 19 torpedo boats of the V Flotilla and the II and XVIII Half Flotillas.

Graudenz

and

Stralsund

were assigned to the forward screen, and

Kohlberg

and

Rostock

to starboard and port respectively. Each light cruiser was assigned half a flotilla of torpedo boats. [25]

Again, the interception and decryption of German wireless signals played an important role. Although they were unaware of the exact plans, Room 40's cryptographers were able to deduce that Hipper would be conducting an operation in the Dogger Bank area. [25] To counter this, Beattie's 1st Cruiser Squadron, Rear Admiral Gordon Moore's 2nd Cruiser Squadron and Commodore William Goodenough's 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron had a rendezvous with Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force at 08:00 24 January, approximately 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) north of Dogger Bank. [25]

At 08:14 Kohlberg

sighted the light cruiser Aurora and several Harwich destroyers.

[26] Aurora

challenged

Kohlberg

with a spotlight, after which

Kohlberg

attacked

Aurora

and scored two hits.

Aurora

returned fire and

scored

two hits on

Kohlberg

.

Hipper immediately directed his battlecruisers to fire when, almost simultaneously, Stralsund

noticed a large amount of smoke northwest of his position. This was identified as several large British warships heading towards Hipper's ships. [26] Hipper later remarked:

The presence of such a large force indicated the proximity of further elements of the British fleet, especially as radio intercepts revealed the approach of the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron... They were also reported by Blücher

in the rear of the German line, which opened fire on a light cruiser and several destroyers coming from the stern... The battlecruisers under my command found themselves, due to the prevailing [east-northeast] wind, in a windward position and from the very beginning in an unfavorable situation. .. [26]

Hipper turned south to escape, but his speed was limited to 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph), which was Blücher's

while.

[f] The pursuing British battlecruisers steamed at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) and quickly overtook the German ships. At 09:52, Lyon opened fire on Blücher

from a range of approximately 20,000 yards (18,000 m);

soon after, the Royal Princess and Tiger also started shooting. [26] At 10:09 the British guns made their first attack on Blücher

.

Two minutes later, the German ships began returning fire, mainly focusing on Lyons

, from a range of 18,000 yards (16,000 m).

At 10:28, Lion

struck the waterline, causing a hole in the ship's side and flooding the coal bunker.

[27] Around the same time, Blücher

scored a shot with a 21 cm shell on

the left

forward turret.

The shell did not penetrate the armor, but had a concussion and temporarily disabled the left gun. [28] At 10:30, New Zealand - the fourth ship in Beatty's line - approached Blücher

and opened fire. By 10:35 the firing range had been reduced to 17,500 yards (16,000 m), after which the entire German line was within effective range of the British ships. Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to engage their German counterparts. [gram]

By 11:00 Blucher

was seriously damaged by numerous heavy shells from British battlecruisers.

However, the three leading German battlecruisers, Seydlitz

,

Derfflinger

and

Moltke

, concentrated their fire on

Lyon

and scored several hits;

two of her three dynamos were disabled and the engine room on the port side was flooded. [29] At 11:48, Indomitable arrived on the scene and was ordered by Beatty to destroy the battered Blücher

, which was already on fire and listing heavily to port. One of the survivors on the ship spoke about the destruction:

Blücher's painting

fire and bad listing

The shells... even reached the fireplace. The coal in the bunkers caught fire. Since the bunkers were half empty, the fire burned happily. In the engine room, the shell drained oil and sprayed it around with a blue-green flame... The terrible air pressure resulting from the [explosion] in a confined space... rumble[ed] through all the openings and [burst] its way through all the weak points... People were picked up by the terrible air pressure and thrown to a terrible death among the machines. [29]

The British attack was aborted due to reports of submarines ahead of the British ships. Beatty quickly ordered evasive maneuvers, which allowed the German ships to increase their distance from their pursuers. [30] At this time, Lion

' She failed her last operating dynamo, reducing her speed to 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph).

Beatty, in the wounded Lion,

ordered the remaining battlecruisers to "attack the enemy's rear", but a signal mix-up forced the ships to target

Blücher

alone.

[31] She continued to stubbornly resist; Blücher

repelled attacks by four cruisers of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron and four destroyers.

However, the flagship of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, Aurora,

Blücher

twice with torpedoes.

By this time, all main battery gun turrets, except the aft one, were silenced. Seven more torpedoes were fired at point blank range; these hits caused the ship to capsize at 13:13. During the battle, Blücher

was hit by 70–100 large-caliber shells and several torpedoes. [32]

As the ship sank, British destroyers headed towards it, attempting to rescue survivors from the water. However, the German airship L5

mistook the sinking

Blücher

for a British battlecruiser and attempted to bomb the destroyers, which withdrew.

[31] Figures vary depending on the number of casualties; Paul Schmalenbach reported that 6 officers out of 29 and 275 enlisted men out of 999 were pulled from the water, resulting in 747 casualties. [32] Official German sources, researched by Erich Gröner, stated that 792 people died in the sinking of the Blücher

, [9] while James Goldrick cited British documents which reported that of a crew of at least 1,200, only 234 survived person.

[33] Among those rescued was Kapitän zur See

(captain at sea) Erdmann, commander

of Blücher

. He later died of pneumonia while in British captivity. [31] Twenty more people would also die as prisoners of war. [32]

Sinking Blucher

rolls over on its side

Commemorative stele of SMS Blücher, Nordfriedhof, Kiel, Germany

Concentration on Blucher

allowed

Moltke

,

Seydlitz

and

Derfflinger

to escape.

[34] Admiral Hipper initially intended to use his three battlecruisers to turn around and outflank the British ships to rescue the battered Blücher

, but when he learned of the serious damage to his flagship, he decided to abandon the armored cruiser. [31] Hipper later spoke about his decision:

To help Blucher,

it was decided to try a flanking move... But I was informed that my flagship turrets C and D were out of action, we were full of water at the stern, and that she only had 200 shells.

Because of the heavy shell, I abandoned further thoughts about supporting Blücher

.

Any such course, now that we could not count on the intervention of our Main Fleet, could lead to further heavy losses. Supporting the Blücher

with a flanking movement would have brought my formation between the British battlecruisers and the battle squadrons that were probably behind. [31]

By the time Beatty regained control of his ships, after he boarded HMS Princess Royal, the German ships had too great an advantage for the British to catch up with them; at 1:50 p.m. he broke off the chase. [31] Kaiser Wilhelm II was enraged by the destruction of Blücher

and the near sinking

of Seydlitz

, and ordered the High Seas Fleet to remain in harbor. Rear Admiral Eckermann was removed from his post and Admiral Ingenohl was forced to resign. He was replaced by Admiral Hugo von Pohl. [35]

The fortress garrison sank a ship with landing forces without orders from Oslo

On April 9, 1940, in the Oslofjord, the German heavy cruiser Blucher with troops on board was sunk by the garrison of the Oscarsborg fortress. This detachment of German ships entered the Oslofjord to land troops and capture the capital of Norway. We will talk about the events preceding this battle, about the Government of Norway and its fantastic illusions, and about the Norwegian military who fulfilled their duty in this article.

Operation Weserubung

Even at the stage of preparation for World War II, Nazi Germany faced the question of resources. Since World War I, Germany has purchased Swedish iron ore. Its concentration from the Kirune deposit in Northern Sweden reached 65%. As of the early 40s of the twentieth century, this ore was considered the most concentrated in the world. German industrialists and the military greatly appreciated the opportunity to use this ore. Annual imports to Germany reached 10 million tons at the end of the 1930s. The issue with Sweden was resolved. The Scandinavian kingdom had long-standing friendly relations with Germany. And, apparently, the Nazis had guarantees of uninterrupted supplies. The issue was the delivery of ore to Germany.

In the summer, ore from the deposit was delivered to the Swedish port of Luleå in the Gulf of Bothnia. From there, ore was transported on cargo ships to German ports. This route was the most reliable, since in case of war it passed through Swedish territorial waters, which ensured uninterrupted supplies. However, this route had one significant drawback. In winter, the Gulf of Bothnia froze, and the number of Swedish icebreakers in the late 1930s was not enough to support regular voyages of iron ore ships. Therefore, in winter, ore was transported by rail to the Norwegian port of Narvik, and from there it was delivered by ship to German ports. For peacetime, the route was safe and relatively reliable. But in the event of the outbreak of war, this route was easily interrupted. The German General Staff made a fundamental decision to capture Norway. It is interesting that in the initial period the Germans were not particularly interested in the capabilities of Norwegian ports in terms of access to the Atlantic. Their main task was to ensure uninterrupted delivery of ore from Narvik. The British also understood this and began to develop similar plans. A race against time began, in which the main prize was the fate of an independent state.

The situation was heating up. The trigger was events called the “Altmark incident.” Its essence was as follows. The Altmark was a large Kriegsmarine tanker that supplied fuel to German raiders in the Atlantic. After another supply operation, the Altmark, with more than three hundred captured English sailors transferred from the “pocket” battleship” - the heavy cruiser “Admiral Graf Spee” in the South Atlantic to a tanker, entered the territorial waters of Norway, believing that he was in security. However, the British made a different decision. The leader of the destroyers "Kossak" - "Kozak" made a daring raid into Norwegian territorial waters and captured a German tanker with captured English sailors. The Norwegian navy observed the incident but did not intervene. When Hitler was informed of the capture, he was furious. It was after this incident that he decided to capture Norway. The essence of the German plan was as follows. The Germans understood that the superiority of the British on the high seas was certainly undeniable, so the only chance of success was to capture all the main ports of Norway in several detachments before the deployment of the English fleet.

On this topic

2066