Mistakes of British shipbuilding. Battlecruiser Invincible. Part 4

In the last article, we examined in detail the technical characteristics of the cruisers of the Invincible project, and now we will figure out how they performed in battle, and finally sum up the results of this cycle. The first battle, near the Falklands, with the German squadron of Maximilian von Spee, is described in sufficient detail in numerous sources, and we will not dwell on it in detail today (especially since the plans of the author of this article include the idea of making a cycle on the history of the raiding squadron of von Spee), but let's note some nuances.

Oddly enough, despite the advantage in gun caliber, neither Invincible nor Inflexible had an advantage in firing range over German cruisers. As we have already said, the firing range of the 305-mm artillery of the first British battlecruisers was about 80.7 cables. At the same time, the German turret installations of 210 mm guns had approximately 10% more - 88 cable guns. True, the casemate 210-mm guns of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau had a lower elevation angle and could only fire at 67 cables.

Therefore, despite all the inequality of forces, the battle still did not become a “one-goal game.” This is evidenced by the fact that the British commander Sturdee considered himself forced to break the distance and move beyond the range of the German guns just 19 minutes after the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau opened fire on the British battlecruisers. Of course, he later returned...

In general, during the battle between the German armored and British battlecruisers, the following became clear.

Firstly, the British were poor at shooting at distances close to the maximum. In the first hour, the Inflexible fired 150 shells at a distance of 70-80 cables, of which at least 4, but hardly more than 6-8, were fired at the light cruiser Leipzig, which brought up the rear of the German column, and the rest at the Gneisenau. At the same time, according to the British, 3 hits were achieved in the Gneisenau - whether this is true or not is difficult to judge, since in battle you often see what you want, and not what actually happens. On the other hand, Infelxible's senior artillery officer, Commander Werner, kept detailed records of hits on the Gneisenau, and then, after the battle, interviewed the rescued officers from the Gneisenau. But it should be understood that this method did not guarantee any complete reliability, since the German officers, taking mortal combat, experienced extreme stress, and yet they still had to perform their official duties. At the same time, they, of course, could not keep track of the effectiveness of British shooting. Assuming that during this period of the battle the British managed to achieve 2-3 hits on the Gneisenau with 142-146 shells fired at it, we have a hit percentage of 1.37-2.11, and this, in general, is almost under ideal shooting conditions.

Secondly, we are forced to admit the disgusting quality of British shells. According to the British, they achieved 29 hits at Gneisenau and 35-40 hits at Scharnhorst. In the Battle of Jutland (according to Puzyrevsky), it took 7 hits from large-caliber shells to destroy the Defense, 15 hits from the Black Prince, and the Warrior, having received 15 305 mm and 6 150 mm shells, eventually died too, although the crew fought for the cruiser for another 13 hours. It is also worth noting that the Scharnhorst-class armored cruisers had armor protection that was even somewhat weaker than the Invincible-class battlecruisers, and yet the Germans did not spend as many shells on any British battlecruiser that perished in Jutland as on the ships of the squadron von Spee. And finally, we can remember Tsushima. Although the number of hits on Russian ships by 12-inch Japanese “suitcases” is unknown, the Japanese spent 446 305-mm shells in that battle, and even if we assume a record 20% of hits, then even then their total number does not exceed 90 - but for the entire squadron, despite the fact that the Borodino-class battleships were protected by much better armor than the German armored cruisers.

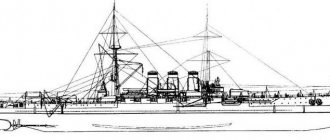

Carefree "Connecticut"

Apparently, the reason for the low effectiveness of British shells was their filling. According to the peacetime standard, the Invincibles were supposed to have 80 shells per 305-mm gun, of which there were 24 armor-piercing, 40 semi-armor-piercing and 16 high-explosive, and only high-explosive shells were loaded with lyddite, and the rest with black powder. In wartime, the number of shells per gun increased to 110, but the proportion between types of shells remained the same. Of the total number of 1,174 shells that the British fired at German ships, only 200 were high-explosive (39 shells from the Invincible and 161 from the Inflexible). At the same time, each fleet tried to use high-explosive shells from a maximum distance, from where they did not expect to penetrate armor, and as they got closer they switched to armor-piercing shells, and it can be assumed (although this is not known for sure) that the British used up their high-explosive shells in the first phase of the battle, when the accuracy of their hits left much to be desired, and the bulk of the hits came from shells filled with black powder.

Thirdly, it once again became clear that a warship is a fusion of defensive and offensive qualities, the right combination of which allows it (or does not allow it) to successfully solve assigned tasks. The Germans shot very accurately in their last battle, achieving 22 (or, according to other sources, 23) hits in the Invincible and 3 hits in the Inflexible - this, of course, is less than the British, but, unlike the British, the Germans They lost this battle, and it is impossible to demand from the beaten German ships the performance of the almost undamaged English ones. Of the 22 hits on the Invincible, 12 were made with 210-mm shells, another 6 with 150-mm shells, and in another 4 (or five) cases the caliber of the shells could not be determined. At the same time, 11 shells hit the deck, 4 – the side armor, 3 – the unarmored side, 2 hit below the waterline, one hit the front plate of the 305-mm turret (the turret remained in service) and another shell broke one of the three “legs” of the British mast . Nevertheless, the Invincible did not receive any damage that would threaten the ship’s combat capability. Thus, the Invincible-class battlecruisers demonstrated the ability to quite effectively destroy the old-type armored cruisers, inflicting decisive damage on them with their 305-mm shells at distances from which the latter’s artillery was not dangerous for the battlecruisers.

The battles of Dogger Bank and Heligoland Bight did not add anything to the fighting qualities of the first British battlecruisers. "Indomiteble" fought at Dogger Bank

But he failed to prove himself. It turned out that the speed of 25.5 knots was no longer sufficient for full participation in the operations of battlecruisers, so in the battle both it and the second “twelve-inch” battlecruiser New Zealand lagged behind the main forces of Admiral Beatty. Accordingly, the Indomiteble did not cause any harm to the newest German battle cruisers, but only took part in the shooting of the Blucher, which was hit by 343-mm shells. Which also managed to respond with one 210-mm shell, which did not cause any damage to the English cruiser (ricochet). Invincible took part in the battle in Heligoland, but at that time the British battlecruisers did not meet an equal enemy.

Another thing is the Battle of Jutland.

All three ships of this type took part in this battle, as part of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron under the command of Rear Admiral O. Hood, who commanded the forces entrusted to him with skill and valor.

Having received the order to link up with David Beatty's cruisers, O. Hood led his squadron forward. The light cruisers of the 2nd reconnaissance group were the first to catch his eye, and at 17.50, from a distance of 49 cables, the Invincible and Inflexible opened fire and inflicted heavy damage on the Wiesbaden and Pillau. The light cruisers turned away, and in order to let them escape, the Germans launched destroyers to attack. At 18.05 O. Hood turned away, because with very poor visibility such an attack really had a chance of success. However, Invincible managed to damage Wiesbaden so that the latter lost speed, which subsequently predetermined its death.

Then, at 18.10, the ships of D. Beatty were discovered on the 3rd squadron of battlecruisers and at 18.21 O. Hood took his ships to the vanguard, taking a position ahead of the flagship Lion. And at 18.20 German battle cruisers were discovered, and the 3rd squadron of battle cruisers opened fire on the Lutzow and Derflinger.

Tu-160M: “White Swan” took wing

Here we need to make a small digression - the fact is that already during the war the British fleet rearmed itself with shells filled with lyddite and the same Invincible, according to the state, should have carried 33 armor-piercing, 38 semi-armor-piercing and 39 high-explosive shells, and by the middle 1916 (but it is unclear whether they made it to Jutland) a new ammunition load of 44 armor-piercing, 33 semi-armor-piercing and 33 high-explosive shells was installed on the gun. However, according to the recollections of the Germans (and that same Haase), the British also used shells filled with black powder in Jutland, that is, it can be assumed that not all English ships received lyddite shells, and what exactly did the 3rd squadron of battlecruisers fire? the author of this article does not know.

But on the other hand, the Germans noted that British shells, as a rule, did not have armor-piercing qualities, since they exploded either at the moment of breaking through the armor, or immediately after breaking through the armor plate, without going deeper into the hull. At the same time, the force of explosion of the shells was quite high, and they made large holes in the sides of the German ships. However, since they did not go inside the hull, their impact was not as dangerous as classic armor-piercing projectiles could have produced.

At the same time, what is liddit? This is trinitrophenol, the same substance that was called melinite in Russia and France, and shimosa in Japan. This explosive is very susceptible to physical impact and could well detonate on its own at the moment of penetration of the armor, even if the fuse of the armor-piercing projectile was set to an appropriate delay. For these reasons, Lyddite does not seem to be a good solution for equipping armor-piercing shells with it, and therefore, no matter what the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron fired at Jutland, there were no good armor-piercing shells among its ammunition.

But if the British had them, the final score of the Battle of Jutland might have been somewhat different. The fact is that, having entered into battle with the German battle cruisers at a distance of no more than 54 cables, the British quickly reduced it and at some point were no further than 35 cables from the Germans, although then the distances increased. In fact, the issue with the distances in this episode of the battle remains open, since the British started it (according to the British) at 42-54 cables, then (according to the Germans) the distances were reduced to 30-40 cables, but later, when the Germans saw “ Invincible” he was 49 cables away from them. It can be assumed that there was no rapprochement, but perhaps there was one. The fact is that O. Hood took an excellent position relative to the German ships - due to the fact that visibility towards the British was much worse than towards the Germans, he could clearly see the Lutzow and Derflinger, but they could not see him . Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that O. Hood maneuvered in such a way as to get as close as possible to the enemy, while remaining invisible to him. To tell the truth, it is not entirely clear how he could determine whether the Germans saw him or not... In any case, one thing can be stated - for some time the 3rd squadron of battle cruisers fought “with one goal.” This is how the senior artilleryman of the Derflinger von Haase describes this episode:

“At 1824 hours I fired at enemy battleships in the direction of the northeast. The distances were very small - 6000 - 7000 m (30-40 cables), and, despite this, the ships disappeared in stripes of fog, which slowly stretched out interspersed with gunpowder smoke and smoke from chimneys. Observing the fall of the shells was almost impossible. In general, only undershoots were visible. The enemy saw us much better than we saw him. I switched to long-range shooting, but because of the darkness it didn’t help much. Thus began an unequal, stubborn battle. Several large shells hit us and exploded inside the cruiser. The entire ship was bursting at the seams and broke down several times to escape the covers. It was not easy to shoot under such circumstances.”

Under these conditions, in 9 minutes, O. Hood's ships achieved excellent success, hitting the Lützow with eight 305 mm shells and the Derflinger with three. Moreover, it was at this time that “Lutzov” received blows that ultimately became fatal for him.

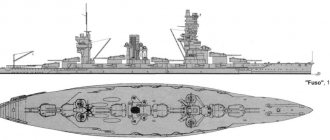

The same "Lutzow"

British shells hit the Luttsov's bow under the armor belt, causing flooding of all bow compartments; water filtered into the artillery magazines of the bow towers. The ship almost immediately took on over 2,000 tons of water, sat with its bow at 2.4 m and, due to the damage indicated, was soon forced to abandon formation. Subsequently, it was these floodings, which became uncontrollable, that became the cause of the death of the Luttsov.

Towards tanks with “pocket artillery”

At the same time, one of the British shells that hit the Derflinger exploded in the water opposite the 150 mm gun No. 1, which caused deformation of the plating under the armored belt at a distance of 12 meters and the filtration of water into the coal bunker. But if this English shell had exploded not in the water, but in the hull of a German battle cruiser (which could well have happened if the British had normal armor-piercing shells), then the flooding would have been much more serious. Of course, this hit in itself could not lead to the death of the Derflinger, but let us remember that it received other damage and, during the Battle of Jutland, took 3,400 tons of water inside the hull. Under these conditions, an additional hole under the waterline could well be fatal for the ship.

However, after 9 minutes of such a war, fortune turned to the Germans. Suddenly, a gap appeared in the fog, in which, unfortunately, the Invincible found itself, and of course, the German artillerymen took full advantage of the opportunity presented to them. It is not entirely clear who exactly and how many hit the Invincible - it is believed that he received 3 shells from the Derflinger and two from the Lutzow, or four from the Derflinger and one from the Lutzow, but it could be and not so. What is more or less reliable is that at first the Invincible received two shells each, which did not cause fatal damage, and the next, fifth shell hit the third tower (abeam tower on the starboard side), which became fatal for the ship. A 305 mm German shell penetrated the armor of the turret at 18.33 and exploded inside, causing the cordite inside to ignite. An explosion followed, throwing up the roof of the tower, shortly after which, at 18.34, the detonation of the magazines occurred, splitting the Invincible in two.

The death of "Invincible"

It is possible that there were more than five hits on the Invincible, because, for example, Wilson notes that hits from German ships were observed near the turret, which received a fatal blow, and in addition, a shell may have hit the bow turret of the Invincible, above which, According to eyewitnesses, a column of fire rose. On the other hand, one cannot rule out errors in the descriptions - what is often seen in battle is not what is actually happening. Perhaps the force of the explosion of the middle turret ammunition was so strong that the bow magazines detonated?

In any case, the battle cruiser Invincible, which became the ancestor of its class of ships, died under concentrated fire from German ships in less than five minutes, taking with it the lives of 1,026 sailors. Only six were saved, including senior artillery officer Danreuther, who was at the center fire control post on the top of the foremast at the time of the disaster.

To be fair, it must be said that no amount of armor would have saved Invincible from destruction. At a distance of just under 50 kbt, even twelve-inch armor would hardly be an insurmountable barrier against the German 305 mm/50 guns. The tragedy was caused by:

1) Unsuccessful design of the turret compartments, which, during an explosion inside the turret, passed the explosion energy directly into the artillery magazines. The Germans had the same thing, but after the battle at Dogger Bank they modernized the design of the turret compartments, but the British did not.

2) The disgusting qualities of British cordite, which was prone to detonation, while German gunpowder simply burned. If the Invincible charges had contained German gunpowder, a strong fire would have occurred, and the flames from the doomed tower would have risen many tens of meters. Of course, everyone in the tower died, but there was no detonation and the ship would have remained intact.

However, let’s assume for a second that the German shell did not hit the tower, or the British would have used the “correct” gunpowder and no detonation would have occurred. But two German battlecruisers fired at the Invincible, and the Koenig joined them. Under these conditions, we have to admit that “Invincible”, in any case, even without the “golden shell” (the so-called particularly successful hits that cause fatal damage to the enemy) was doomed to death or complete loss of combat effectiveness, and only very powerful armor would give does he have any chance of survival?

The second “twelve-inch” battlecruiser to perish in Jutland was Indefatigable. It was a ship of the next series, but the armor of the main caliber artillery and the protection of the magazines was very similar to the Invincible-class battlecruisers. Just like the Invincible, the Indefatigable's turrets and barbettes had 178 mm of armor up to the upper deck. Between the armor and the upper deck of the barbette, the Indefatigable was protected even slightly better than its predecessor - 76 mm versus 50.8.

Promising US and NATO anti-missile projects

It was the Indefatigable that was destined to demonstrate how vulnerable the defense of Britain's first battlecruisers was over long combat distances. At 15.49, the German battle cruiser Von der Tann opened fire on the Indefatigable - both ships were at the end of their columns and were supposed to fight each other. The battle between them lasted no more than 15 minutes, the distance between the cruisers increased from 66 to 79 cables. The English ship, having spent 40 shells, did not achieve a single hit, but the Von der Tann at 16.02 (i.e. 13 minutes after the order to open fire) hit the Indefatigable with three 280-mm shells that hit it at the level of the upper deck in the area of the aft tower and mainmast. The Indefatigable went out of order to the right, with a clearly visible list to the port side, while a thick cloud of smoke rose above it - in addition, according to eyewitnesses, the battlecruiser landed stern-wise. Soon after this, two more shells hit the Indefatigable: both hit almost simultaneously, the forecastle and the main caliber bow turret. Soon after this, a high column of fire rose in the bow of the ship, and it was enveloped in smoke, in which large fragments of the battle cruiser were visible, that is, a 15-meter steam boat flying upside down. The smoke rose to a height of 100 meters, and when it cleared, the Indefatigable was no longer there. 1,017 crew members were killed, only four were saved.

Although, of course, nothing can be said for sure, but, judging by the descriptions of the damage, the fatal blow to the Indefatigable was dealt by the first shells that hit the area of the aft tower. German semi-armor-piercing shells of 280-mm Von der Tann cannons contained 2.88 kg of explosives, high-explosive shells - 8.95 kg (data may be inaccurate, as there are contradictions in the sources on this matter). But in any case, the explosion of even three shells weighing 302 kg, which hit at the level of the upper deck, could not lead to a noticeable list to the left side, and damage to the steering looks somewhat doubtful. In order to cause such a sharp roll and trim, the shells had to hit below the waterline, hitting the side of the ship below the armor belt, but eyewitness descriptions directly contradict this scenario. In addition, observers note the appearance of thick smoke above the ship - a phenomenon uncharacteristic of being hit by three shells.

Most likely, one of the shells, having hit the upper deck, hit the 76 mm barbette of the aft turret, pierced it, exploded and caused the detonation of the aft artillery magazine. As a result of this, the steering turned around, and water quickly began to flow into the ship through the bottom, which was broken by the explosion, which is why both the list and trim arose. But the aft tower itself survived, so observers saw only thick smoke, but not the flames of the explosion. If this assumption is correct, then the fourth and fifth shells simply finished off the already doomed ship.

The question of which of them caused the detonation of the bow tower cellars remains open. In principle, the 178-mm armor of a turret or barbette with 80 cables could withstand the impact of a 280-mm projectile, then the explosion was caused by a second projectile that hit the 76 mm barbette inside the hull, but this cannot be said for sure. Moreover, even if the Inflexible’s cellars had contained not British cordite, but German gunpowder, and detonation had not occurred, still two severe fires in the bow and stern of the battle cruiser would have led to the complete loss of its combat effectiveness and, probably, it would have been destroyed anyway. Therefore, the death of the Indefatigable should be attributed entirely to the lack of its armor protection, and especially in the area of the artillery magazines.

The series of articles brought to your attention is entitled “Mistakes of British shipbuilding”, and now, summing up, we will list the main mistakes of the British Admiralty made during the design and construction of battlecruisers of the Invincible class:

The first mistake made by the British was that they missed the moment when their armored cruisers, due to their protection, ceased to satisfy the task assigned to them of participating in squadron battle. Instead, the British chose to increase artillery and speed: the defense was dominated by an unfounded tendency to “and so will do.”

Their second mistake was that, when designing the Invincible, they did not realize that they were creating a ship of a new class and did not bother at all with defining the range of tasks for it, or determining the necessary tactical and technical characteristics to meet these tasks. To put it simply, instead of answering the question: “What do we want from a new cruiser?” and after that: “What should the new cruiser be like to give us what we want from it?” the position prevailed: “Let’s create the same armored cruiser as we built before, only with more powerful guns, so that it corresponds not to the old battleships, but to the newest Dreadnought.”

Tasks of special national importance

The consequence of this mistake was that the British not only duplicated the shortcomings of their armored cruisers in ships of the Invincible type, but also added new ones. Of course, neither the Duke of Edinburgh, nor the Warrior, nor even the Minotaur were suitable for squadron combat, where they could come under fire from the 280-305 mm artillery of battleships. But the British armored cruisers were quite capable of fighting against their “classmates.” The German Scharnhorst, the French Waldeck Russo, the American Tennessee, and the Russian Rurik II did not have any decisive advantage over the British ships, even the best of them were approximately equivalent to the British armored cruisers.

Thus, British armored cruisers could fight against ships of their class, but the first British battlecruisers could not. And what’s interesting is that such a mistake could be understood (but not excused) if the British were sure that the opponents of their battlecruisers, as before, would carry 194-254 mm artillery, the shells of which could still be protected by the Invincibles. then resist. But the era of 305-mm cruisers was opened not by the British with their Invincibles, but by the Japanese with their Tsukuba. The British were not pioneers here; they were, in fact, pushed to introduce twelve-inch guns on large cruisers. Accordingly, it was not at all a revelation for the British that the Invincibles would have to face enemy cruisers armed with heavy guns, which the defense “like that of the Minotaur” obviously could not withstand.

The third mistake of the British is an attempt to put a “good face on a bad game.” The fact is that, in the open press of those years, the Invincibles looked like much more balanced and better protected ships than they really were. As Muzhenikov writes:

“...naval reference books, even in 1914, attributed to the Invincible-class battlecruisers armor protection along the entire waterline of the ship with a 178-mm main armor belt, and gun turrets with 254-mm armor plates.”

And this led to the fact that the admirals and designers of Germany, the main enemy of Great Britain at sea, selected the performance characteristics for their battlecruisers so as to withstand not real, but ships invented by the British. Oddly enough, perhaps the British should have stopped the exaggerations in the bud and made public the true characteristics of their cruisers. In this case, there was a small, but still non-zero, probability that the Germans would become “monkeys” and, following the British, also began to build “eggshells armed with hammers.” This would not, of course, strengthen the defense of the British, but at least equalize the chances in the confrontation with the German battlecruisers.

In essence, it was the inability of the British battlecruisers of the first series to fight on equal terms with ships of their class that should be considered the key mistake of the Invincible project. The weakness of their defenses made ships of this type a dead-end branch of naval evolution.

When creating the first battlecruisers, other, less noticeable mistakes were made, which could be corrected if desired. For example, the main caliber of the Invincibles received a small elevation angle, as a result of which the range of the 305 mm guns was artificially reduced. As a result, the Invincibles were inferior in terms of firing range even to the turret-mounted 210-mm guns of the latest German armored cruisers. To determine the distance, even in the First World War, relatively weak, “9-foot” rangefinders were used, which did not cope very well with their “duties” at a distance of 6-7 miles and beyond. The attempt to “electrify” the 305-mm turrets of the lead “Invincible” turned out to be a mistake - at that time, this technology was too tough for the British.

In addition, it should be noted the weakness of British shells, although this is not a disadvantage exclusively of the Invincibles - it was inherent in the entire Royal Navy. English shells were filled with either liddite (i.e. the same shimosa) or black (not even smokeless!) gunpowder. As a matter of fact, the Russo-Japanese War showed that gunpowder as an explosive for shells had clearly exhausted its usefulness, while at the same time shimosa turned out to be overly unreliable and prone to detonation. The British managed to bring the liddite to an acceptable state, avoiding problems with shell explosions in the barrels and spontaneous detonation in the cellars, but still the liddite was of little use for armor-piercing shells.

The German and Russian fleets found a way out by filling the shells with trinitrotoluene, which showed high reliability and ease of operation, and in its qualities was not much inferior to the famous “shimosa”. As a result of this, by 1914 the Kaiserlichmarin had excellent armor-piercing shells for their 280 mm and 305 mm guns, but the British had good “armor-piercing shells” after the war. But, we repeat, the poor destructive quality of British shells was then a general problem for the entire British fleet, and not an “exclusive” design flaw of ships of the Invincible type.

Special forces of the Russian Federation and the USA: a race of improvements

Of course, it would be wrong to assume that the first English battlecruisers consisted only of shortcomings. The Invincibles also had advantages, the main of which was a super-powerful for its time, but quite reliable power plant, which gave the Invincibles previously unimaginable speed. Or recall the high “three-legged” mast, which made it possible to place a command and rangefinder post at a very high altitude. But still, their advantages did not make the Invincible-class battlecruisers successful ships.

What was happening at that time on the opposite shore of the North Sea?

Thank you for your attention!

Previous articles in the series: Mistakes of British shipbuilding. Battlecruiser "Invincible" Errors of British shipbuilding. Battlecruiser Invincible. Part 2 Mistakes of British shipbuilding. Battlecruiser Invincible. Part 3

List of used literature

1. Muzhenikov V.B. Battlecruisers of England. Part 1. 2. Parks O. Battleships of the British Empire. Part 6. Firepower and speed. 3. Parks O. Battleships of the British Empire Part 5. At the turn of the century. 4. Ropp T. Creation of a modern fleet: French naval policy 1871-1904. 5. Fetter A.Yu. Invincible-class battlecruisers. 6. Materials from the site https://wunderwaffe.narod.ru.

Who has more?

The almost 20-year “sea race” between Germany and Great Britain made the main participants the owners of the world's largest battlefleets, but if for Great Britain sea power was familiar, then for Germany it was a new condition. The First World War was supposed to determine the winner of the race, but while the conflict quickly became large-scale, covering Europe with front lines from the North Sea to the Swiss border and from the Baltic Sea to Romania, it just as quickly became clear that the attack at sea “with a saber” "nakedly" neither side is ready.

The growing superiority of the British largely determined the tactics of both sides in the North Sea. The German High Seas Fleet sought its fortune in raiding operations of battlecruisers against the British coast and shipping in the North Sea, counting on the release of part of the enemy forces from the base, which could be lured into a trap and destroyed, thereby correcting the unfavorable balance of forces. In the event that the unit turned out to be too strong, the Germans had to retreat. The British, in turn, hoped to one day lure the entire High Seas Fleet (or, at least, a significant part of it) from the base, so that, having destroyed the enemy, they would radically resolve the issue of supremacy at sea.

David Beatty

The clash at the Dogger Bank in January 1915 was a very valuable experience for the Germans. A British 343-mm shell knocked out both stern turrets of the battle cruiser Seydlitz with four 280-mm guns. The fire spread to the ammunition magazines, but there was no explosion, and the ship returned home, having lost 159 people out of 1068 crew. Based on the results of the work of the commission that investigated the causes of the incident, changes were made to the design of the ammunition supply systems for the main-caliber guns on German battleships and battlecruisers: the shell and powder elevator shafts were equipped with automatically closing doors, and the supply of powder charges began to be carried out in a fire-resistant closure made of copper, rubber and leather. These measures could not completely eliminate fires, but the likelihood of an explosion or burnout of ammunition magazines decreased many times over.

The Royal Navy, which avoided being hit by turrets and ammunition supply systems, did not receive such experience - and this seriously affected the course of the upcoming general battle, which neither side even suspected in January 1915.

Pieces on the board

On the morning of May 31, 1916, the British believed that they would have to deal with the vanguard of Hochseeflotte - the 1st and 2nd reconnaissance groups under the overall command of the chief of reconnaissance forces, Rear Admiral Franz Hipper. They did not yet realize that the main forces under the overall command of Scheer had gone to sea.

John Rushworth Jellicoe

The general situation looked like this: Admiral Sir John Rushworth Jellicoe, who commanded the Grand Fleet, had under his command three combat squadrons (in order of formation 2nd, 4th and 1st), which included six divisions of battleships - in total 24 units, including the flagship battleship Iron Duke, which was not part of any of the formations. The main hopes, however, rested on the fifth combat squadron of Rear Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas. It included only four ships, unlike the first four formations, but these were the latest high-speed battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class, well armored, armed with 381-mm main battery artillery and developing a full speed of 24 knots, which was three knots higher than the maximum speed columns of the main forces. They were assigned a special task: due to their high speed, they were supposed to accompany the faster battle cruisers of David Beatty, providing him with overwhelming fire superiority over the German vanguard of Franz Hipper, and at the same time insuring the weakly protected battle cruisers in case of a sudden appearance of the main forces of the Germans. When the main forces met, they were supposed to play the role of the “fast wing” of the Grand Fleet, ensuring coverage of the “head” of the enemy formation.

"Magnificent cats": battlecruisers "Lion", "Princess Royal" and "New Zealand"

Image: britishbattles.com

The basis for the formation of the British vanguard under the command of Beatty, in addition to the 5th combat squadron attached to it, was the 1st and 2nd squadrons of battlecruisers consisting of five ships. Beatty himself still held the flag on the battlecruiser Lion, formally, like the Iron Duke, which was not part of any formation. The third squadron of battlecruisers of Rear Admiral Horace Hood, consisting of three more ships, was assigned to the Grand Fleet and was supposed to come under Beatty's command after meeting with the enemy.

A total of 42 heavy Royal Navy ships went into battle, accompanied by 109 cruisers, destroyers and auxiliary ships. The firepower of the main forces was 272 guns: 48 381 mm, 10 356 mm, 110 343 mm and 104 305 mm. The weight of the broadside of the British ships was 150.76 tons.

Battleship Barham

Image: nrscotland.gov.uk

The main forces of Hochseeflotte looked much more modest: the battle line consisted of two squadrons (3rd and 1st), which included four divisions of battleships and, like the British, the flagship Friedrich der Grosse." Franz Hipper's vanguard, consisting of two reconnaissance groups, consisted of five battlecruisers and five light cruisers.

In addition, on the last day before the departure, Reinhard Scheer ordered the inclusion of the 2nd squadron of battleships, consisting of six pre-dreadnought battleships, in the High Seas Fleet, in order to partially compensate for the superiority of the British in heavy guns. The downside was the low speed and poor protection of outdated battleships, which rather hampered the actions of the main forces of the fleet. In total, the Germans brought into battle 27 heavy ships armed with 200 guns - 128 305 mm and 72 280 mm. The weight of the German broadside was 60.88 tons. The light forces were accompanied by 11 light cruisers and 61 destroyers. The overall ratio in terms of the number of pennants was 151 versus 99 in favor of the British.

Don't quarrel with codebreakers

The next operation of the German High Seas Fleet, scheduled for May 17-18, 1916, did not involve a battle with the main enemy forces. The Germans were preparing for another raiding operation of battlecruisers on the coast of northeastern England, hoping to draw part of the forces of the British Grand Fleet to sea, luring the enemy to their main forces. In case the enemy's main forces left the bases, the Germans planned reconnaissance with airships, which would allow them to escape in time if the enemy brought superior forces to sea.

Reinhard Scheer

In addition, a curtain of submarines was deployed off the coast of Britain. However, it was not possible to start the operation on time: the repairmen only completed work on the already familiar Seydlitz on May 22, 1916, which at the end of April received further damage after being blown up by a mine. Admiral Reinhard Scheer, commander of the High Seas Fleet, did not want to start an operation without one of the best battlecruisers with an excellent crew. Seydlitz was finally ready for departure on May 28, but by this time the weather had deteriorated and it became impossible to use the airships.

However, everything was already ready to go to sea, and the submarines deployed to the position in advance had to go home on June 1 due to exhaustion of supplies, and Scheer simply decided to change the pattern of the operation. The plan now called for battlecruisers to enter the Skagerrak Strait to disrupt commercial shipping. The ultimate goal remained the same luring out the enemy, but the change in geographical position allowed the British to approach only from the west, and reconnaissance in this direction was supposed to be carried out by destroyers and light cruisers.

The British, in turn, planned their own operation to lure the Germans into battle: two cruiser squadrons were supposed to pass through the Skagerrak and Kattegat straits, reach the Sound Strait and return back, forcing the German battle cruisers to take the bait. The main forces of the Grand Fleet were supposed to close the trap for Franz Hipper.

As a result, by the end of May 1916, the main forces of the fleets on both sides were ready “for battle and campaign.” Of the 32 existing British dreadnoughts, 28 ships were ready: the Royal Sovereign, which entered service on May 25, had not yet reached combat readiness, and the Queen Elizabeth, Emperor of India and the founder of the class, with the commissioning of which ten years earlier, the race reached the finish line - His Majesty's Ship "Dreadnought" was under repair. The battlecruiser Australia was also undergoing repairs. The battleships König Albert, which was under repair due to problems with the power plant, and the newest Bayern, which had entered service two months earlier and was undergoing combat training in the Baltic, were excluded from the list of the main forces of the Germans.

In preparation for the operation, the Germans took camouflage measures - radio silence was not introduced so that the quiet air would not reveal the fact of preparation, but a number of call signs changed owners. Thus, the call sign DK, which belonged to Scheer’s flagship ship, the battleship Friedrich der Grosse, was transmitted to the coastal radio station. In addition, messages received a second level of encryption, which made them difficult to read even though the British knew the basic German cipher.

The British, however, noticed the preparation of the Germans, and the fact of the transfer of the call signs of the German flagship to the coastal station was recorded even earlier by the “40th room”, but the British were unable to open the exit to the sea of the Friedrich der Grosse and the main forces of the fleet: strained relations between cryptographers The “40th room” and the operational department of the Admiralty led to the fact that when asked about the location of the call sign DK, the codebreakers answered “DK is in Jade” (Jade Bay, on the shore of which the city and the naval base of Wilhelmshaven are located), without specifying the identity of the call sign.