Sea ram

In October 1932, construction of the warship Kharkov began at the Nikolaev shipyards. In 1934, it launched, and four years later it entered service with the Black Sea Fleet. The ship belonged to the class of modern leaders of destroyers at that time. According to the tactical and technical specifications, during its construction the experience of the battles of the First World War was taken into account.

The leader "Kharkov" was distinguished by its lightness, speed of 43.57 knots (80 km/h) and was armed with both torpedo and artillery weapons. It carried 76 mines and had four anti-aircraft machine guns on board to fend off attacks from the sky. In essence, the leader is a ram, which was supposed to lead destroyers into battle and be the first to attack enemy warships and convoys. Its length was 127.5 meters with a width of 11.7 meters. The team included 243 officers and sailors.

On the second day of the Great Patriotic War, the ship participated in the installation of minefields. In the early morning of June 26, the Kharkov and the destroyer Moskva attacked the Romanian port of Constanta. Each ship fired 35 salvos from five guns. A fire started on the shore, and the ships were ordered to leave. The smoke screen did not prevent the German Tirpitz battery from knocking out the Moscow, which died. Nazi guns began to hit Kharkov.

The shells hit the ship and at the same time Romanian fighters attacked it. Water hammer from explosions led to the destruction of ship boilers, and then oil tanks. "Kharkov" began to lose speed, but following the course in an anti-artillery zigzag, it managed to escape from the fire of the "Tirpitz" battery. Right at sea, the team began repairs, but the enemy was on the trail of the wrecked ship.

The second round was left to the Soviet sailors, who shot down one of the two Romanian bombers that attacked them. In the third round, an unidentified submarine approached the leader. The submarine fired a torpedo. Captain 3rd Rank Pyotr Melnikov conducted a maneuver, and she passed astern. The destroyer Soobrazitelny came to the aid of the Kharkov. Together they sank an enemy submarine and retreated to Sevastopol.

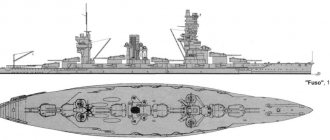

TTD:Displacement: 2597 tons. Dimensions: length - 127.5 m, width - 11.7 m, draft - 4.18 m. Maximum speed: 43.57 knots. Cruising range: 1800 miles at 20 knots. Powerplant: 3 shaft PTU, 66,000 hp. Armament: 5x1 130 mm, 2 76.2 mm, 2 45 mm, 10 37 mm guns, 4 12.7 mm machine guns, 2x4 533 mm torpedo tubes, 76 min. Crew: 243 people.

Ship history:

The 1st shipbuilding program, adopted by the Council of Labor and Defense in December 1926 and marking the beginning of the Soviet period of military shipbuilding, did not provide for the renewal of the fleet's destroyer forces. However, already in 1928, in connection with the transition of Soviet industry to 5-year development plans, the program was revised. In its new form (1929), it included, among others, destroyers. The tactical and technical specifications for the design of Project 1 destroyers were approved on November 1, 1928 (in 1933 they were reclassified as leader destroyers). The design was carried out at the Central Design Bureau of Special Shipbuilding (TsKBS-1) under the leadership of chief designer V.A. Nikitin. It was planned to build three such ships.

On November 1, 1928, the tactical and technical specifications for the design of the leader of destroyers were approved. Before this, a comparative analysis of destroyers built abroad after the First World War was carried out and their development trends were determined. It was necessary to create ships that were superior in their combat qualities to their foreign counterparts. The expediency of creating a new class of surface ships was also suggested by the experience of the First World War. It was necessary to expand the capabilities of destroyers by strengthening artillery weapons. In this regard, intermediate ships between light cruisers and destroyers appeared with predominantly torpedoes and highly developed artillery weapons, called leaders. Light but well-armed, high-speed leaders were capable of leading destroyers in a torpedo attack on enemy warships and guarded convoys.

The creation of such a ship (project 1) was an important milestone in the development of domestic surface shipbuilding. This was the first experience in designing and building a ship that was quite large at that time, which brought shipbuilders close to creating light cruisers. Many of the technical solutions found during this process were subsequently used both in the adjustment of Project 1 and in the construction of ships of other classes.

The leader "Kharkov" was laid down on October 29, 1932 at plant No. 198 in Nikolaev, launched on September 9, 1934, and entered service on November 10, 1938.

The pre-war years of the Kharkov leader were spent in exercises and scheduled repairs. At the beginning of June 1941, "Kharkov" as part of the squadron took part in exercises to test the interaction of the fleet with the troops of the coastal flanks of the army. A day before the start of the war, he returned to Sevastopol and took his regular place in the bay. Already on June 23, the leader as part of a group of ships participated in providing mine laying, and on June 24, together with the 3rd division of OLS destroyers, he went out to cover the coast of Crimea from the expected raid of Romanian destroyers.

On June 25, "Kharkov" (the lead one in the strike group of ships) at 20.10 with the commander of the strike group, Captain 2nd Rank Romanov on board, left Sevastopol to strike Constanta. Early in the morning of June 26, turning on a given course and increasing speed when crossing the line of a Romanian minefield, Kharkov lost its paravanes. After reaching the turning point on a combat course of 55°, he opened fire from the main caliber from a distance of 130 kbt. The first salvo was deliberately fired with an undershoot of 3 kbt in order to check the correct direction of fire from the resulting bursts, since due to the pre-dawn haze there was poor visibility of the horizon.

Having made sure of the accuracy of the aiming, we switched to killing with the second salvo. The leader fired five-gun salvoes every 10 seconds. Fires broke out on the shore. In ten minutes, both leaders fired 35 salvos and fired 350 130-mm shells. After the enemy returned fire at 5.10, the commander of the strike group gave a VHF signal: “Start retreat. Smoke,” duplicating it with a white rocket from the left side. "Kharkov" set out on a retreat course and, increasing speed to 30 knots, went into the wake of the leader "Moscow" in an anti-artillery zigzag, trying not to leave the smoke screen set by the lead ship.

A powerful explosion broke the Moskva in half, and 280-mm shells from the German Tirpitz coastal battery began to explode near the Kharkov. At the same time, the ship was attacked by Romanian fighters. We had to stop rescue work and leave immediately. At 5.28 the leader was covered. One shell exploded 10 m to the right of the bow, producing a strong hydrodynamic shock to the hull, and streams of water from the explosion fell on the bridge. The second shell fell astern.

The ship, having reached a speed of 20 knots, began to sharply reduce it to 6 knots: due to a disruption in the water circulation due to the forced speed in boiler No. 1, the water-heating tube burst. At 5.36 boiler No. 1 completely failed; its load was taken by boilers No. 2 and No. 3. At the same time, due to close shell explosions in the third boiler room, the turbofan regulator was reset, and the speed of the Kharkov decreased even more. Air attacks continued - a raid by two bombers followed: one bomb fell 3 kbt on the bow of the ship, and the second on the stern. The difficult situation forced the commander of the strike group to send a radiogram to the flagship cruiser: “I fired at oil tanks, I need help.” The commander of the cover group sent the destroyer Soobrazitelny to help the leaders. At 5.50 Romanov was forced to send a second radiogram to Voroshilov asking for help.

Finally, Kharkov managed to escape from the artillery fire of the Tirpitz battery. At that moment, the distance from the coast reached 19 miles, from the place of death of the Moscow - 5 miles. But the enemy aircraft were still pursuing the leader - during the next raid of two bombers, one of them was shot down by anti-aircraft artillery. At 5.58 in boiler No. 2, 3 tubes in a small bundle burst, and the speed dropped again to 5 - 6 knots. The movement of the ship was now provided only by boiler No. 3. With the commissioning of the turbofan on the starboard side of boiler No. 3, the speed was increased to 14 knots. At about 6 o'clock, the commander of BC-5 ordered the pipes of the slowly cooling boiler No. 1 to be turned off and put into operation. Such work is usually carried out in a cooled boiler, but in extreme conditions the repairs had to be carried out in a hot one. The work of plugging the pipes on the side of the steam manifold was completed in 5 minutes, and on the side of the water manifold in 8. In general, the repair work on the first boiler was completed in two and a half hours instead of the required 10-16. Now the leader of “Kharkov” could make a bigger move.

At half past six, while repair work was underway, a new attack by enemy aircraft began. The leader managed to turn left, and the bombs landed 5 kbt behind the stern of the ship. At 6.43 the turbofan on the left side of boiler No. 3 failed, and again the speed dropped to 5 knots. At this time, the Kharkov, which had traveled a little more than 8 miles from the place of the death of the Moskva, was attacked by an unidentified submarine. The signalmen discovered an air bubble and the trail of a torpedo heading towards the leader on the right at a heading angle of 70° at 25 - 30 kbt. I had to turn sharply, and the torpedo passed one and a half cables astern. In turn, the leader’s gunners fired diving shells at the supposed location of the boat.

Exactly at 7.00, the destroyer Soobrazitelny, which finally approached to guard the damaged ship, noticed the trace of a second torpedo at a heading angle of 50° on the starboard side. The destroyer turned right in time, and the torpedo passed on the left side. Five minutes later, the destroyer discovered the trace of a third torpedo, traveling along the starboard side of the Soobrazitelny in the direction of Kharkov. A semaphore signal was sent to the leader, and he turned right in time. The destroyer passed over the salvo and dropped two series of depth charges. The boat (presumably it was Shch-206) sank, and the Kharkov and Soobrazitelny, repelling the attacks of the bombers, headed for Sevastopol.

At 8.14, boiler No. 1 on the leader was put into operation, and the ship under two boilers reached a speed of 26 knots. At noon, the destroyer Smyshlyny joined the guard of Kharkov. An hour later, all three ships were subjected to a final attack by an enemy bomber, which lasted 20 minutes. It ended to no avail: at the moment the bombs were dropped, the Kharkov and both destroyers made a turn “all of a sudden” and the bombs fell to the side. Then the ships moved on, changing courses and speed, and at 21.30 they arrived in Sevastopol.

The events of the war did not allow time for rest. Intensive repairs at the base - and the leader “Kharkov” is back in action. Already on July 20, he, together with the destroyer "Bodriy", went to the area of the island of Fidonisi (Snake) to cover the withdrawal of the Danube military flotilla from the mouth of the Danube to Odessa.

During the defense of Odessa, "Kharkov" made flights with a load of ammunition and supported the actions of ground units. In total, during the period from August 25 to September 8, the leader opened fire on enemy positions 66 times. On September 15, he ensured the passage of 18 ships with evacuated troops from Odessa to Sevastopol.

In September, "Kharkov" stopped in Novorossiysk for scheduled maintenance. At the same time, the first seaborne radio beacon (MKR) in the Black Sea Fleet was installed on it, connected to a directional coastal radio beacon operating on it.

On October 31, the leader of “Kharkov” left Novorossiysk and on November 1, before dawn, arrived in Sevastopol. In the afternoon, during the next enemy air raid, about a dozen bombs exploded on the left side and on the bow of the leader standing on the barrel, without causing him much harm. But after this, the ships of the squadron began to be based in the ports of the Caucasian coast; “Kharkov” was given a place in Novorossiysk.

From November 1941 to February 1942, the leader was used to transport reinforcements and ammunition to the main base. In addition, he was used to shell the coast occupied by the enemy. On December 5, after unloading in Sevastopol, the Kharkov, standing at the wall in the bay, fired at enemy personnel in the area of the village of Aksu. During the return fire, a shell hit the armor shield of the leader's first gun. As a result, the gun was put out of action, the superstructures, the wardroom, and the sight of gun No. 2 were damaged by shrapnel. The base command decided to repair the ship on its own - it was transferred to Korabelnaya Bay and placed at the artillery workshops. And even during repairs, he continued to fire from the stern guns.

On December 21, upon entering Sevastopol, the Kharkov was attacked by bombers, and when approaching the boom gate, it also came under artillery fire from enemy coastal batteries. To throw off the aim, the leader, unable to deviate from the fairway, maneuvered with a sharp change in speed. At a speed of about 21 knots, under heavy battery fire, she passed the boom gate and moored at the artillery pier without receiving any hits. Then “Kharkov” fired at enemy reserves accumulated in the area of the Mekenzievy Gory station, at cordon No. 1, in Belbek and Duvankoy. During the two days that the ship was at the main base (until December 23), it expended 618 130-mm shells.

On the night of January 28-29, 1942, “Kharkov” with troops, ammunition and food on board broke into besieged Sevastopol. On January 30, February 1 and 2, before leaving for Novorossiysk, “Kharkov” again fired at enemy positions, and on the transition to the Caucasus coast on February 4, it fired at enemy positions in the Crimea. On the night of February 27-28, the leader as part of the OLS went out to fire at German troops near Feodosia.

On March 6, "Kharkov", which was receiving marching replenishment, ammunition and food in Novorossiysk, received an order to urgently go to sea to assist the destroyer "Smyshlyny", which was blown up by a mine in the area of Cape Zhelezny Rog (Kerch Strait). By the time the leader approached, the heavily damaged destroyer had left the defensive minefield under its own power. “Kharkov” had only to lead the detachment to Novorossiysk. However, at night, due to strong winds and huge waves, the destroyer could not be controlled, and the Kharkov tried to take it in tow. “Smyshlyi” was turned around by the waves and capsized. Depth charges began to roll off the overturned destroyer and explode dangerously close to the leader. Due to strong hydraulic shocks, mechanisms and instruments on it began to fail: a magnetic compass flew out of the binnacle, and the repeater from the gyrocompass of the helmsman was torn off. For more than two hours, “Kharkov” maneuvered at the site of the death of “Smyshlyny”, but was able to save only two sailors. During one of the turns, he crashed at full speed into the crest of the “ninth wave” wave. A huge mass of water bent the forecastle deck and a crack formed. The vertical supports of the deck in the wardroom turned out to be bent into an arc. We had to change course and instead of Novorossiysk follow the wave to Poti only, since going against the wave was very risky.

In Poti, emergency repairs were carried out - water was pumped out from the premises, the supports were straightened, the damaged upper deck of the forecastle was restored, and bent hatches, doors and fenders were straightened. The very next day, the leader left for the main base, delivering marching reinforcements, ammunition and food there.

On March 8 and 9, Kharkov exchanged artillery fire with the enemy and suppressed two enemy batteries. On March 24, 27, 31 and April 6, “Kharkov”, together with other ships and transport vessels, transported cargo, guns and other equipment from the Caucasian coast to Sevastopol. He repeatedly fired at enemy positions, while being subjected to retaliatory strikes from artillery and aircraft.

On April 7, while maneuvering in the Sevastopol Bay near the wall, the leader hit the pier hard with the stem. As a result of the impact, the lower part of the stem was bent to the right, and the hull plating was damaged. Literally overnight the building was repaired. And for the accurate fire, as a result of which three German batteries were suppressed, the ship’s crew received the gratitude of the fleet commander.

May 1942 also turned out to be very tense for Kharkov. From May 9 to May 15, at night, he left Poti to the Feodosia Gulf and to the coast of the Kerch Strait to fire at enemy troops. On May 18, while crossing from Novorossiysk to Sevastopol, the Kharkov was attacked by aircraft. The leader's anti-aircraft gunners managed to shoot down two planes, but due to close bomb explosions, the ship lost control. The covering on a large part of the rudder blade was torn off, and the fairing on the right propeller came off. In Novorossiysk, the Kharkov was placed on a floating dock and repaired within two days.

On June 17, the leader and his troops set off on their usual campaign, heading for the besieged fortress city. For the purpose of operational camouflage, at first he went in a southern direction, simulating a flight to the Caucasian port. At dawn on June 18, Kharkov turned towards Sevastopol and was immediately subjected to an intense Luftwaffe raid. During the 22nd bombing at 6.50, one of the bombs exploded under the stern of the leader. A fire broke out in the 3rd boiler room, the 5th cellar was flooded, and due to the influx of sea water in the main boilers, the salinity increased. The first vehicle stalled, salinity was detected in the oil supply tanks, and the 3rd and 4th main caliber guns failed. The fire was extinguished. The salinity was corrected by replacing broken pipes in the main refrigerator. Damage to the steering hydraulics was repaired in the tiller compartment. After sealing the ruptured seams in the 5th artillery cellar, the water was pumped out. At the request of the leader’s commander, an order was received from the chief of staff to go to Poti under the cover of the “Tashkent” leader.

By the beginning of August 1942, the OLS of the Black Sea Fleet was reorganized into a brigade of cruisers, while Kharkov became part of the 1st division of destroyers. On August 2 at 17.18 the leader "Kharkov" and the cruiser "Molotov" left Tuapse, with the task of carrying out a raid operation on the port of Feodosia and Dvuyakornaya Bay. At 0.59 the leader opened fire on targets and fired 59 130 mm shells in 5 minutes. At 1.13, the detachment discovered by the enemy set off on a retreat course. German torpedo bombers and Italian torpedo boats MAS-568 and MAS-573 began pursuit. When attacking a torpedo boat, the leader covered it with a second salvo and dodged the fired torpedo. But the Molotov cruiser was unlucky: it was hit by a torpedo and the explosion tore off 20 m of the stern along with the rudder. Fortunately, the cruiser did not lose the ability to move and control vehicles and continued to move away at a 14-knot speed. The leader accompanied him to Poti. In this operation, they repelled 10 attacks by torpedo boats and the same number of air raids. Having expended 868 anti-aircraft shells, he shot down one plane (together with a cruiser) and damaged another.

During the September enemy offensive on Novorossiysk and Tuapse, Kharkov was repeatedly called upon to provide fire support for ground forces. On the morning of September 1, as part of a detachment, he went to sea to shell the coast of Crimea, and on the way back at 22.30, maneuvering in Tsemes Bay from a distance of 100 kbt, he fired at a concentration of enemy troops and military equipment on the approaches to Novorossiysk. True, the expected result was not achieved - the shooting was carried out across squares from too great a distance (13 km). On the night of September 2-3, the Kharkov, anchored in the roadstead, fired at the village of Krasnomedvedkovskaya. This time the results were more successful. The enemy suffered significant damage in manpower and equipment - 6 tanks, 14 guns, 22 vehicles, and about an infantry battalion were destroyed. Over these two nights, the leader fired 399 shells.

On October 14, the enemy resumed a powerful offensive in the North Caucasus. At this critical moment, in order to eliminate the breakthrough of enemy troops in the Novorossiysk area, “Kharkov” and the ships of the Black Fleet squadron urgently transferred three guards rifle brigades from Poti to Tuapse in five days of October - a total of about 10 thousand soldiers with weapons. Later, on October 21 and 22, the ship was used to transport troops in Tuapse, as well as for fire support for troops in Novorossiysk.

In the autumn-winter period of 1942, Kharkov, as part of detachments of surface ships, made three raids on enemy communications off the western shores of the Black Sea. So, on November 29 - December 2, the leader of a detachment of ships raided the island of Fidonisi. On December 19, he took part in the night shelling of Yalta.

In January 1943, the ship underwent scheduled repairs. On the night of February 3-4, 1943, the leader of “Kharkov” as part of a detachment left Batumi for the South Ozereyka - Stanichka area for artillery preparation in the landing area. A similar operation was carried out by the leader on the night of February 14. During the summer of 1943, Kharkov was repeatedly involved in operations to shell enemy positions in the Crimea and disrupt enemy communications in the Kerch Strait.

But in October the irreparable happened. The purpose of the operation on October 6 was the destruction of German watercraft and landing ships returning from Kerch, as well as the shelling of the ports of Feodosia and Yalta. To carry out the task, the leader "Kharkov", the destroyers "Besposhchadny" and "Sposobny", eight torpedo boats and the naval air force were allocated.

With the onset of darkness on October 5 at 20.30, the ships left Tuapse. At about one o'clock in the morning on October 6, "Kharkov", with the permission of the detachment commander, began moving towards Yalta. At 2.30 an enemy reconnaissance aircraft was spotted on it, which was reported to the detachment commander G.P. Negoda (the pennant braid was on the Besposhchadny). At 5.04 the plane dropped flare bombs. The ships changed courses, but could not hide the true direction of their movement, since, as it turned out, their movement was monitored by the enemy’s coastal radar service.

At 6.30 "Kharkov" began shelling Yalta from a distance of 70 kbt. In 16 minutes, he fired at least 104 130-mm high-explosive fragmentation projectiles without adjustment. Following along the coast, the leader fired 32 shots at Alushta, but, as it turned out, all the shells were overshot. The leader's fire was answered by three 75-mm guns of the 1st battery of the 101st division, and then six 155-mm guns of the 1st battery of the 772nd division of the enemy. At 7.15, "Kharkov", maneuvering under the fire of coastal batteries, began to retreat and joined the returning destroyers.

At 8.10, three Soviet fighters that appeared over the formation shot down a German reconnaissance plane, and the pilots splashed down with parachutes. The ships were delayed 20 minutes to be boarded. This maneuver diverted the attention of the top watch from observing the horizon. And as soon as the ships began to retreat at a 28-knot speed, 8 German Ju-87 dive bombers, covered by two Me-109s, took advantage of this. And although Soviet fighters shot down one Junkers and one fighter, other planes that came from the direction of the sun managed to hit the leader with three bombs weighing 250 kg at once.

One of them hit the upper deck in the area of the 135th frame and, having pierced the hull right through, exploded under the keel. Another bomb hit the first and second boiler rooms. Both of them, as well as the engine room, were flooded; water slowly flowed through the damaged bulkhead on the 141st frame into the third boiler room. Thus, of the main power plant, the turbo-gear unit in the second engine room and the third boiler remained in service, the pressure in which dropped to 5 kg/cm2. The motor pump in the second car, diesel generator No. 2, and turbofan No. 6 were damaged by the shock. The explosion tore off and threw one 37-mm anti-aircraft gun overboard; two anti-aircraft machine guns were out of action. The leader lost speed, received a list of 9° to starboard and a trim on the bow of about 3 m.

In this situation, Sposobny was ordered to take Kharkov in tow, stern first. Now the formation was moving 90 miles from the Caucasian coast west of Tuapse at a speed of 6 knots. It would be possible, having assessed the situation, to remove the crew from the leader and sink the ship. This order was allegedly given by the fleet commander. But at the junction they did not receive the order and continued to move. At 11.50, 14 Ju-87 dive bombers appeared above the ships. Two of them attacked Kharkov and Sposobny, the rest attacked Besposchadny. And although by this time 9 more of our fighters had arrived on call, they were unable to repel the Luftwaffe’s attacks. “Kharkov” did not receive any new damage, but “Besposhchadny” was hit by an aerial bomb, which destroyed the engine room, and “Sposobny”’s rivet seams came apart as a result of the bombing. After this, the detachment commander gave the order to “Sposobny” to alternately tow “Kharkov” and “Besposhchadny”.

At 14.00, the third boiler on the leader was put into operation, and the ship was able to speed up to 10 knots under one engine. But 10 minutes later the ships were again attacked from the air by a group of 20 - 25 Junkers. As a result, at 14.25, the “Merciless” sank. At this time, "Kharkov" received two direct hits in the forecastle, several bombs exploded next to the ship. All the bow rooms up to the 75th frame were flooded, the strong shaking of the hull caused the auxiliary mechanisms of the only boiler remaining under steam to fail, and the leader began to plunge with its bow, listing to starboard. There was no time to carry out any significant measures to combat survivability, and at 15.37, firing from a 130-mm gun and one anti-aircraft gun until the last moment, the Kharkov disappeared under water.

The commander of the leader P.I. Shevchenko was saved by “Sposobny”. For another two hours, the destroyer saved the leader’s crew. But at 18.10 another German air raid followed, and 20 minutes later the destroyer Sposobny was killed by the explosion of its own depth charges.

This ship was commanded at different times by: - captain 3rd rank / captain 2nd rank Melnikov P.A. (09.1939 - 06.1942); - Captain 3rd rank Shevchenko P.I. (06.1942 - 06.10.1943)

Destroyer Leaders: The Vanished Class

The leaders of destroyers disappeared into history virtually after the end of World War II.

And the blame for this fact lies entirely with the destroyers. But let's go in order. The class itself, or, to be precise, a subclass of torpedo-artillery ships, was invented by the British back in the First World War. Initially, the term “leader of destroyers” sounded like “leader of a flotilla of destroyers.” In those years, the British fleet operated such formations as flotillas of destroyers and destroyers. And the leader of the flotilla was usually the ship on which the flotilla commander and his staff were located.

Usually the role of the leader was played by the first ship in the series. During construction, the placement of the flotilla headquarters on it was taken into account, since this meant an increase in the crew. Along with the commander of the destroyer formation, the same ship housed the flotilla headquarters, flagship radio operators, cipher operators, and signalmen. And this is a considerable number of people that had to be accommodated and provided with everything necessary.

If we get down to the numbers, the standard Royal Navy Tribal-class destroyer had a crew of 183 people. And in the “leader” configuration - 223. Otherwise, these ships were no different from their classmates.

The Germans followed approximately the same concept when they implemented the idea of a “divisional destroyer” at the end of the 19th century. These were ships larger than destroyers, and in addition to the headquarters they carried a supply of repair materials, mine workshops and an infirmary. One such “divisional destroyer” accounted for 5-7 conventional destroyers.

In the Soviet naval classification, a leader is a ship of the destroyer subclass, but with a larger displacement, greater speed and enhanced artillery armament. The main purpose is to launch destroyers into an attack and provide support during withdrawal.

But in general, in the world, leaders were called both ships built to support and control destroyers, and warships not intended for such tasks.

For example, French “destroyers”, Italian “scouts”, German “destroyers”, British “fighters”. As a result, the leaders were unarmored or lightly armored torpedo and artillery ships, which occupied an intermediate position between destroyers and light cruisers.

By the beginning of the First World War, certain tasks for leaders had arisen. The leader had to do the following:

1. Serve as the flagship of destroyer flotillas. That is, as stated above, the leader was the operational-tactical command of the flotilla.

2. Launch your destroyers in a torpedo attack. Based on point 1, it was from the leader that the command issued target designations and adjusted tasks.

3. Fight enemy destroyers. For this, the leader had to have more powerful weapons.

Great Britain

In 1905, the Royal Navy solved this problem by introducing light scout cruisers. Or leaders. "Sentinel", "Forward", "Pathfinder", "Adventure" had a displacement of slightly less than 3000 tons, light armor, an armament of ten 76-mm cannons and a speed of 25 knots. Which is quite comparable to the destroyers of that time. And the advent of steam turbines, which caused an increase in the speed of ships, also led to the construction of new leaders.

In 1911-13, Boditsea, Blond and Active appeared, the speed of which increased to 30 knots, and the artillery had a caliber of 102 mm.

British Scout leaders sparked a wave of imitations in Italy, Austria-Hungary, the USA and other countries. Although in Britain itself, scout leaders were considered a failed project.

The first full-fledged leaders were ships of the Shakespeare class. Having gone through the difficult path of creating leaders through the failures of the Lightfoot, Grenville and Faulknor projects, the British created ships that became role models for a long time.

"Shakespeare" and its "classmates" had a displacement of 2000 tons, a speed of 36 knots and a range of 5000 miles at 15 knots. Armament consisted of 5 120-mm guns and torpedo tubes.

After the end of the First World War, the construction of destroyers for the British fleet ceased for a long time, and only in 1928 the British laid down the first series of post-war destroyers - type A.

It was assumed that for each of the “alphabetical” eight destroyers, a flotilla leader would be built, slightly larger in size and somewhat more heavily armed. The first British leader of the post-war flotilla was Codrington. Compared to the A-class destroyers, it had almost 200 tons more standard displacement and one more 120 mm gun, but was significantly less maneuverable.

Further, impressed by the cost of the Codrington, the British began to practice simply converting the destroyer into a leader. For example, the leader of the B-class destroyers Kate lost one of her 120mm guns to accommodate her headquarters. The headquarters premises were located on the Kempenfelt leader due to the removal of anti-submarine weapons.

Subsequently, the British nevertheless returned to the practice of building reinforced fleet leaders. This is how Exmouth, Faulknor, Grenville and Hardy came into being. With a slight increase in displacement, they received a fifth, additional 120 mm gun. The last leader of the flotilla, built according to a special project, was Inglefield.

Starting with the J type, fleet leaders were no longer built according to special designs, but were equipped from standard destroyers and differed only in the volume of quarters for the command staff. Therefore, the composition of the standard flotilla was reduced to eight units, and ships of the “leader” subclass were no longer built in the UK.

Italy

The Italians picked up the idea of their British colleagues, but presented it in the theme of a light reconnaissance cruiser. Initially, ships of the Carlo Mirabello type (1917) were conceived precisely as destroyer leaders. A displacement of almost 2000 tons, a speed of 35 knots and a cruising range of 2300 miles at 15 knots with a very solid armament of 8 102-mm guns made it possible to speak of success.

Even the installation of a 152 mm gun instead of two 102 mm bow guns could not spoil these ships. But in fact, the Italians failed to transform the cruiser into a leader.

In addition, the Italians simply did not give the Romanians four destroyers built on their order and introduced them into their fleet as leaders of the Aquila class. The Aquila had a displacement of 200 tons less than the Carlo Mirabello and had almost the same speed, but a slightly shorter range (1,700 miles).

But on these ships the Italians were able to cram a battery of 3 152 mm guns and four auxiliary 76 mm guns. It turned out a little hard, and after the end of the First World War, all Italian leaders received 120 mm guns.

A further development of the Italian leaders, the Leone class, with which the Italian Navy entered World War II, were not very outstanding ships. Displacement is 2650 tons, speed is the same 35 knots, range is 2000 miles at 15 knots. The armament consisted of 8 (4x2) 120-mm guns, there was anti-aircraft artillery (2 40-mm machine guns, 2x2 20-mm), 2 two-pipe TA and 60 mines.

"Panther"

By the beginning of the war, the ships were actually outdated, but took part in hostilities. All three leaders (Lion, Panther and Tiger) were scuttled by their crews in April 1941 in the Red Sea.

"Navigatori"

Subsequently, the Italian fleet, having experimented with Navigatori-class destroyers, abandoned the idea of the leaders, focusing on light cruisers.

Germany

Watching the evolution of German destroyers, it is generally difficult to say whether they had leaders at all. In general, German shipbuilding thought developed according to some of its own canons and gave the world several ships, about which many years later there are disputes about their ownership. This also applied to “pocket battleships”, the same applies to destroyers.

Speaking about German destroyer leaders, it’s worth starting the conversation with the S-113 project. This was the real response of the Germans to the appearance of destroyers of increased tonnage among the eternal enemies of the British.

For 1916 these were masterpiece ships. Displacement 2500 tons, speed 36 knots, range 2500 miles at 20 (!) knots. In terms of armament at that time, these ships had no analogues. 4 150 mm guns, 4 600 mm torpedo tubes, mines.

Yes, there were many shortcomings in the design of the ships; difficulties were noted with firing from 150-mm guns in rough seas. However, the S-113, which came to France in 1920 as a trophy, became a model in the development of tactical and technical specifications for the design of the first French large Jaguar-class counter-destroyer.

The further development of German destroyers took place under the sign of “more and more.” And it is worth noting that, in terms of their parameters, the ships that Germany began to build after Hitler came to power were more consistent with leaders than with destroyers.

Series 1934. Z-1 "Leberecht Maas". Displacement 3150 tons, speed 38 knots, range 1900 miles at 19 knots. Armament: 5 127 mm guns, air defense (2 × 2 - 37 mm, 6 × 1 20 mm), 2 four-tube torpedo tubes 533 mm.

Series 1936B, Z-43. Displacement 3507 tons, speed 38 knots, range 2900 miles at 19 knots. Armament: 5 127 mm guns, air defense (2 × 2 - 37 mm, 16 × 1 20 mm), 2 four-tube torpedo tubes 533 mm, 4 bomb launchers, 30 depth charges and 76 barrage mines.

If you look at the German destroyers, you understand that the Hipper or Scharnhorst were quite suitable for their leadership. Which, in fact, is what happened.

France

Before World War I, the French fleet did not have ships of this class. After the end of the war, Italy began to be considered the main “potential enemy”, and the Mediterranean Sea was considered the main theater of operations.

Considering the fact that the Italian fleet had a significant number of destroyers, which were superior to the ships of this class that the French then had, and the appearance of the Leone-class ships among the Italians, it was decided to develop a counterweight.

Since the construction of new cruisers was significantly limited by the terms of the Washington Treaty, it was decided to create a new class of torpedo-artillery ships, called “counter-destroyers” or “destroyer fighters”, which were supposed to operate in homogeneous formations - divisions of three units and squadrons of two divisions. They were not intended to lead destroyers. They were entrusted with reconnaissance tasks, combating light forces and torpedo attacks on battleships.

The study of the captured German S-113 led to the appearance of the Jaguar class ships.

"Jackal"

Displacement 3050 tons, speed 35 knots, range 2900 miles at 16 knots. Armament: 5 130 mm guns, 2 75 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 550 mm three-tube torpedo tubes.

It cannot be said that the first French counter-destroyers turned out to be successful ships. The “pure” French destroyers “Bourrasque”, which were built at the same time, with a standard displacement of 1,500 tons, carried slightly less powerful weapons. However, the Jaguar, Panther, Lynx, Leopard, Jackal and Tiger played their role in the development of a new class of ships.

A further development was the Cheetah type. Six ships were built: “Bison”, “Cheetah”, “Lion”, “Valmy”, “Vauban”, “Verdun”. All ships of this type were lost during hostilities, with only the Bison killed in battle, and the remaining five were sunk in Toulon on November 27, 1942 during the self-destruction of the French fleet.

"Buffalo"

Displacement 3200 tons, speed 35 knots, range 3000 miles at 14 knots. Armament: 5 138 mm guns, 4 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 coaxial 13.2 mm machine guns, 2 550 mm three-tube torpedo tubes.

This was followed by the Aigle type. Ships of this class were significantly better than the Cheetahs.

"Milan"

Displacement 3140 tons, speed 36 knots, range 3500 miles at 18 knots. Armament: 5 138 mm guns, 4 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 coaxial 13.2 mm machine guns, 2 550 mm three-tube torpedo tubes.

Better quality ships, however, their fate was sad. Only the Albatross survived the war. "Aigle", "Gerfaut" and "Vautour" were sunk by their crews in Toulon in 1942, and "Epervier" and "Milan", damaged in battle by the Anglo-American squadron, were thrown ashore in the Casablanca area.

Leaders of the “Vauquelin” type, development of leaders of the “Aigle” type. A total of six units were built: “Vauquelin”, “Tartue”, “Kersen”, “Mahieu Breze”, “Cassar”, “Chevalier Paul”. In terms of performance characteristics, they actually did not differ from the Aigle type, with the exception of a reduction in the cruising range to 2800 miles at 14 knots.

"Maie Breze"

The Maillet Bréze was destroyed by the explosion of its own torpedo in 1940, the Chevalier Paul was sunk by British torpedo bombers near Latakia on June 16, 1941, and the rest were sunk in Toulon.

Leaders like "Le Fantask". Developing Vauquelen-type leaders. A total of six units were built in the series: “Le Triomphant”, “Le Fantasque”, “Le Malain”, “L’Audacier”, “Le Terrible”, “L’Endomtable”. Also known as "Le Terrible" type leaders.

These larger, and, needless to say, beautiful ships became the pinnacle of development of French counter-destroyers and a kind of “calling card” of the French fleet. The combination of high firepower with excellent performance made them extremely dangerous for Italian destroyers and serious opponents for Italian light cruisers. As torpedo and artillery ships they can be rated very highly.

The disadvantage of these leaders was that they were intended only for combat with surface enemies. The fight against submarines was practically impossible for them due to the lack of means of detecting them, and the air defense of the ships turned out to be too weak. However, they were good ships.

Displacement 3380 tons, speed 37 knots, range 4000 miles at 17 knots. Armament: 5 138 mm guns, 4 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 coaxial 13.2 mm machine guns, 3 550 mm three-tube torpedo tubes, a bomb releaser and 16 depth charges.

Of the six leaders who took part in World War II, L'Audasier (sunk in the port of Bizerte by Allied aircraft) and L'Endomtable (sunk in the port of Toulon by American aircraft on March 7, 1944) did not survive to the end war.

Type "Mogador". The last series of actually built French leaders. Two ships were built, the Mogador and the Volta. Both were scuttled in Toulon, although before that they took part in battles against the English fleet in North Africa.

Displacement 4018 tons, speed 39 knots, range 3000 miles at 20 knots. Armament: 8 138 mm guns (4x2), 2 twin 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 twin 13.2 mm machine guns, 3 three-tube torpedo tubes and 2 two-tube 550 mm torpedo tubes.

Leaders of the "Mogador" type were created for a very specific tactical task - acting as a reconnaissance officer as part of a strike and reconnaissance group led by battlecruisers of the "Dunkirk" type. It must be admitted that the idea was unsuccessful. Without a seaplane or radar on board, the Mogadors had very modest capabilities to search for the enemy.

If we compare the Mogador and the Volta with similar ships of foreign fleets, there are not many of them. In fact, these are the Soviet leader "Tashkent" and the Italian reconnaissance cruisers of the "Captain Romani" type. All of them were an attempt to create some kind of “intermediate” ship, between the classes of destroyers and cruisers. But the attempt against Mogador was successful.

Russia/USSR

An attempt to implement the concept of a counter-destroyer or leader of destroyers was already in Imperial Russia with the construction of a series of Izyaslav-class destroyers.

Ships of this type were the most powerful in armament and the largest among the destroyers of the Russian fleet of that time, in fact they were leaders, although officially this class of ships did not yet exist in pre-revolutionary Russia.

Displacement 1400 tons, speed 35 knots, range 1880 miles at 21 knots. Armament: 5 102 mm guns, 1 76 mm anti-aircraft gun, 3 457 mm three-tube torpedo tubes.

The experience of the First World War, in which Novik-class destroyers often played the role of light cruisers, became the basis for the program for creating the Soviet destroyer leader. In addition, the impossibility of building modern light cruisers in the early 30s predetermined increased interest in the leaders.

The design task for the first Soviet leader was issued in 1930. The new project was created “from scratch”, without any prototype, by designers who did not have serious experience in designing such large ships. The leaders of “Project 1” were laid down in 1932 as destroyers, and were reclassified as leaders during construction.

Tests have shown that the seaworthiness and stability of the leaders of Project 1 are completely insufficient, the buoyancy reserve is very small, vibration is high at full speed, and the hull turned out to be so weak that it could break even with slight sea waves. It was planned to build six units, but due to the identified shortcomings, it was decided to build the next ships according to an improved design.

So the Leningrad, Moscow and Kharkov entered service with the Soviet Navy.

Displacement 2582 tons, speed 40 knots, range 2100 miles at 18 knots. Armament: 5 130 mm guns, 2 76 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 45 mm anti-aircraft guns, 2 533 mm four-tube torpedo tubes.

The leader of the "Moscow" died during a raid by a naval strike group of four ships of the Black Sea Fleet of the USSR Navy on Constanta on June 26, 1941.

The leader of "Kharkov" died on October 6, 1943 from the actions of German aircraft during a raid by a detachment of Soviet ships and boats on the southern coast of Crimea.

"Leningrad" took part in hostilities as part of the Baltic Fleet.

Then there was a series of leaders of Project 38. In them, the shipbuilders tried to eliminate at least the obvious shortcomings of Project 1. In fact, the changes boiled down mainly to the abandonment of the most negative features of their predecessors. The leaders had solid artillery and torpedo weapons and high speed. At the same time, their hulls were fragile, their seaworthiness and cruising range were insufficient, and their anti-aircraft weapons were extremely weak.

The performance characteristics of the leaders of project 38 were no different from project 1.

The leader "Minsk" took part in the hostilities of the Baltic Fleet.

The leader of “Baku” (laid down in Komsomolsk-on-Amur as “Kiev”, renamed “Ordzhonikidze”, then “Baku” in 1940) was first part of the Pacific Fleet, and when in May 1942 the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command adopted decision to transfer several modern warships from the Pacific Ocean to the Northern Fleet, made the transition from Vladivostok to the Yugorsky Shar Strait, thereby becoming one of the first Soviet warships to cross the Northern Sea Route from east to west.

After the transfer of the EON-18 ships, by order of the fleet commander Golovko dated October 24, 1942, a brigade of destroyers was created as part of the Northern Fleet from three divisions, and the leader of “Baku” headed the 1st division.

While serving in the Northern Fleet, the Baku accompanied allied transports and convoys, participated in raid operations on enemy communications, and was part of the escort ships that provided escort for the convoys. On March 6, 1945, by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, “Baku” was awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

The leader of "Tbilisi" was the only leader of destroyers in the Pacific Fleet during the Great Patriotic War. The fighting was limited to one landing operation.

Tashkent stands separately on the list of leaders. Built by the Italians, the ship differed from its domestic counterparts in its powerful weapons, comfortable conditions for the crew, high speed and a respectable cruising range. According to his drawings, they planned to build three more ships at Soviet factories, but the incompatibility of Soviet technology with Italian technology did not allow this to happen.

Displacement 4175 tons, speed 43 knots, range 5030 miles at 20 knots. Armament: 6 130 mm guns (3x2), 2 76 mm anti-aircraft guns, 6 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, 6 12.7 mm anti-aircraft machine guns, 3 533 mm three-tube torpedo tubes.

The Tashkent leader traveled 27,000 miles, convoyed 17 transports without loss, transported 19,300 people, 2,538 tons of ammunition, food and other cargo. Conducted 100 live firings with the main caliber, silencing 6 batteries, and damaging one airfield. Shot down and damaged 13 enemy aircraft. Sank a torpedo boat.

He died on July 2, 1942 in Novorossiysk as a result of a German air raid.

Results and conclusions

By the beginning of World War II, the leaders were considered as a class of fast artillery and torpedo ships intermediate between light cruisers and destroyers, the purpose of which was:

Suppression of enemy leaders and destroyers.

Ensuring the protection of our ships from attacks by enemy torpedo forces.

Deploying your destroyers into attacks against enemy forces.

Tactical reconnaissance.

Use of torpedo weapons.

Mine installations.

However, during military operations there were no recorded cases of destroyers being launched by leaders into a torpedo attack. In reality, battles involving the use of torpedo weapons by destroyers took place either between the destroyers themselves or with the participation of cruisers. These ships did not perform as expected and as super-destroyers.

If the French counter-destroyers were quickly withdrawn from the war by the surrender of France, and the Soviet leaders and Italian scouts were mainly solving tasks that were not at all intended for them, then the German heavily armed destroyers attempted to conduct naval battles with the surface enemy, but did not show themselves on the positive side. Particularly characteristic was the battle in the Bay of Biscay on December 28, 1943, when two British light cruisers, one of which was outdated, confidently defeated a German force of five super-destroyers and six destroyers without suffering any losses.

By the middle of the war, destroyers had transformed from small attack ships into escort combat units, protecting the main forces of the fleet from air and submarine threats. At the same time, they could take part in the battle of heavy ships, but this was no longer their main task.

The history of the leader subclass was short-lived. The experience of combat use showed that neither in the First nor in the Second World Wars the leaders had to launch destroyers on the attack. And even if this happened, without having an overwhelming advantage over the destroyers, the leader probably could not do this.

The main reason for the disappearance of leaders from the classification of warships was the change in the very nature of naval warfare. Battles between surface forces gradually lost their importance; torpedo attacks by destroyers became rare and rather the result of a successful combination of circumstances. The class of destroyers turned primarily into escort ships for air defense and anti-aircraft defense, and such destroyers no longer needed leaders.

Sources: Dashyan A.V., Patyanin S.V., Mityukov N.V., Barabanov M.S. Fleets of the Second World War. Platonov A.V., Apalkov Yu.V. German warships 1939-1945. Patyanin S.V. Leaders, destroyers and destroyers of France in the Second World War. Kofman V.L. Leaders of the "Mogador" type. Kachur P.I., Morin A.B. Leaders of destroyers of the USSR Navy. Kachur P.I. “Hounds” of the Red Fleet. "Tashkent", "Baku", "Leningrad". Rubanov O. A. Destroyers of England in the Second World War.

Kharkov (leader of destroyers)

"Kharkiv"

- leader of the Project 1 destroyers, built for the Soviet Navy. The leader of "Kharkov" took part in battles as part of the Black Sea Fleet during the Great Patriotic War.

The laying of the Kharkov took place on October 19, 1932 on the slipway of shipbuilding plant No. 198 named after Andre Marti; the ship was launched on September 9, 1934. After completion of the tests, on November 10, 1938, “Kharkov” became part of the 3rd Division of the Light Forces Detachment of the Black Sea Fleet[1][2].

In the pre-war years, the leader of “Kharkov” participated in exercises and scheduled repairs. At the beginning of June 1941, "Kharkov" as part of the squadron took part in exercises to test the interaction of the fleet with the troops of the coastal flanks of the army. A day before the start of the war, he returned to Sevastopol and took his regular place in the bay. Already on June 23, the leader as part of a group of ships participated in providing mine laying, and on June 24, together with the 3rd division of OLS destroyers, he went out to cover the coast of Crimea from the expected raid of Romanian destroyers. After a day of maneuvering in a given area, the ships returned to base - the command’s assumption of an amphibious landing turned out to be erroneous[1].

On June 25, the leader "Kharkov" accompanied the leader "Moscow" in his first and last battle (the raid on Constanta), and when he was blown up, the "Kharkov" was forced to leave the crew of the drowning leader broken in half and flee from shelling by a coastal battery, attacks by a submarine and air bombing simultaneously. During a hasty return to base, several times the leader encountered breakdowns in the boilers (pipes burst), and because of this, the leader’s speed often dropped to 5-6 knots (until the problems in one of the boilers were corrected), but despite this, the ship successfully dodged bombs and repelled air attacks (it shot down one Ju 87). After some time, the damaged leader dodged torpedoes from the Soviet submarine Shch-206 that attacked him, which was immediately sunk by the destroyer Soobrazitelny, which came to the aid of the Kharkov. This version contradicts archival data[3].

On September 6, the leader "Kharkov" with the destroyer "Dzerzhinsky" was sent to Odessa with a cargo of small arms and ammunition on board. Three enemy batteries began to fire at the passage to the port, but the leader nevertheless entered the city and unloaded, after which he fired at the enemy positions and went back to the sea[1].

On September 15, he ensured the passage of 18 ships with evacuated troops and civilians from Odessa to Sevastopol.

The death of "Kharkov". The fateful day of the Black Sea Fleet

Chapter six. Attack on Crimea and naval battle

The night sky was just beginning to brighten a little when our ships approached the place designated for the start of the operation. At 4:00 a.m., “Besposhchadny” and “Sposobny” set a heading of 330 degrees and increased their speed to 28 knots with the expectation of approaching the starting point for firing at the Feodosia port by 5:30 a.m. Soon, from a distance of 200-220 cables from the shore, a flashing light was seen, giving a combination of letters - “live” and “zebra”. What it was remains a mystery. Negoda suggested that this was some kind of signal combination transmitted by a German patrol ship.

Meanwhile, the destroyers were already between Cape Megan and Koktebel. They approached the shore, decided on a place and lay down at the starting point for shooting. At that moment, enemy planes appeared above the destroyers again. This time they dropped SABs (lighting aerial bombs) between the shore and the ships, hoping to illuminate them for coastal batteries. Then, as before, when the destroyers were illuminated, the planes dropped several high-explosive bombs, which fell in the wake of the ships.

The SABs illuminated the sea, and now the destroyers were clearly visible from the shore. In order to avoid being caught in the light background, Negoda ordered to move further to the sea. Eight miles from Feodosia, Koktebel’s coastal artillery suddenly opened fire on the destroyers. Although the aircraft attacks and the fire of coastal batteries did not cause any damage to the ships, it became clear that the Germans were already ready to repel the raid operation and their response was only a matter of time. The operation had already been completely disrupted, and now it was necessary to move away from the Crimea as quickly as possible, until the Germans sent large forces of bomber aircraft against the ships.

From the protocol of the interrogation on December 17, 1943 of the head of the operational planning department of the operational department of the headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet, captain 2nd rank V.A. Eroshenko: “Question: Show me what you know about this operation?

Answer: The ships entered the operation according to the plan, the transition was according to the scheme, during the transition from 02.00 to 04.00, enemy aircraft illuminated the ships with SABs. The first report about this at the fleet headquarters was received at about 02.30 on October 6, 1943 under subscription number 02210. The commander of the leader “Kharkov” reported this. At about 06.00, a report was received from Captain 2nd Rank Negoda that, due to strong enemy opposition, he abandoned the operation and began to withdraw as planned.”

From the interrogation of the Chief of Staff of the Black Sea Fleet, Rear Admiral I.D. Eliseeva: “At 7.30 Negoda reported to the FCP that the tasks were not completed, because he encountered opposition from coastal batteries, torpedo boats and aircraft, so he began to withdraw. As when receiving the first radiogram, I did not make any decisions on this radiogram, believing that the commander of the operation, Romanov, would make a decision himself, based on the current situation.”

So, in the current situation, G.P. Negoda quite reasonably decides to abandon firing at Feodosia and orders the commanders to begin retreating to link up with the Kharkov leader. However, here too, for some reason, the division commander limited himself to half measures. Instead of notifying the Kharkov about the termination of the operation and leaving the Crimean coast at maximum speed, he, walking in an anti-submarine zigzag, decides to simultaneously check the enemy’s communications off the coast. In general, it is possible to understand Negoda: if the operation has already been completely disrupted, then, perhaps, at least while leaving, it will be possible to meet and destroy some German ship along the way. Don’t return home empty-handed when hundreds of German transports are roaming somewhere nearby!

But time! It ran inexorably, and with every minute the chances of our sailors getting to their shores alive became smaller and smaller.

At this moment, two enemy ships were discovered on the horizon. According to Negoda’s memo, these were two high-speed landing barges (LDBs) heading in the direction of Sudak. According to the political report, these were torpedo boats.

According to German data, on the approach to the Crimean coast at 5:30 am, the destroyers and the German submarine U-9 unsuccessfully attacked. However, our ships did not notice this attack. At least, this attack is not noted in any document from our side.

At 5:30 a.m., on a clear zigzag course, from a distance of 60–65 cables, “Besposhchadny” and “Sposobny” opened fire on the barges (or torpedo boats). At the same time, Negoda did not try to get closer to the discovered ships.

This is precisely the moment in the second volume of the military-historical essay “The Navy of the Soviet Union in the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945.” and is described as the time when Negoda transmitted the message about his discovery by German planes! What kind of planes are there, when by this time, in addition to the planes, it had long been discovered and fired upon by enemy coastal artillery, and now it was even conducting a naval artillery battle with enemy ships! Let us note that the division commander could not help but report to the fleet command post that he was fired upon by the Koktebel battery and had a clash with enemy ships. Apparently, he transmitted this radiogram at 5:30 am. As for the message about the discovery of ships by German planes, I am still more inclined to believe that Negoda conveyed it at the latest after the third night attack on destroyers by enemy aircraft, that is, at approximately 4 o’clock in the morning (as he wrote in his report) .

After several barrage salvoes at self-propelled barges (or torpedo boats), the commander of the “Merciless” Parkhomenko approached Negoda, who was standing on the bridge of the destroyer, and asked him for permission to turn around in the opposite direction in order to destroy the discovered barges (boats). The commander of “Merciless” can also be understood. For the first time since the beginning of the war, a destroyer of the Black Sea Fleet had a unique opportunity to fight in a classic naval battle with the enemy, and with undoubted chances of success. In any case, both barges and boats were inferior in artillery to the destroyer. After the war, according to the German side, it became known that our ships fought not with the BDB, but with torpedo boats S-28, S-42 and S-45.

Negoda refused the request to the commander of the "Ruthless". He would later be criticized for this in a number of post-war books. However, I think that the division commander did the right thing in this case. It was already dawn, German bombers were about to appear in the sky, and therefore the journey was not just a minute - every second. The detachment commander ordered the fire on the enemy ships to stop and continue to zigzag to connect with the leader "Kharkov".

From the interrogation on December 25, 1943 of the former commander of the destroyer “Besposhchadny”, captain 2nd rank V.A. Parkhomenko: “Question: At what time did the shelling of the port of Feodosia begin?

Answer: The ships did not fire at the port of Feodosia. At 5.20, the ships, which had already entered the Feodosia Gulf, but not reaching the combat tack, were again illuminated by SABs, attacked by torpedo boats and fired upon by coastal batteries. Enemy aircraft dropped a series of bombs, but missed. Having repelled the attack of torpedo boats, on the orders of the division commander Negoda, we set out on a retreat course to complete the second task - viewing the enemy’s communications and destroying his watercraft from Cape Meganom to Alushta. We discovered two BDBs (1.) and fired at about 14 cables from a long distance, but to no avail.”

Protocol of interrogation on November 3, 1943, as a witness of the assistant commander of the destroyer “Sposobny”, Lieutenant Commander I.G. Frolova: “When Besposhchadny and Sposobny came within sight of the shore, they were attacked by 3-4 torpedo boats. Fire was opened on the boats from both destroyers. During a new attack by enemy aircraft, no fire was fired at the aircraft. I don’t know the number of aircraft, but 3-4 SABs and 4 bombs were dropped on the right stern of the Sposobny and 4 on the left bow of the same destroyer. The attack by the boats was repulsed, the ships did not receive damage, because the enemy boats were not allowed close. After the attack by the boats “Besposhchadny” and “Sposobny”, they set out on a retreat course without firing at the intended targets. We went to the rendezvous point with the leader of “Kharkov”.

The results of the fleeting artillery battle between our destroyers and German ships are not documented. According to the political report, when the torpedo boats were fired upon by the Besposhchadny and Sposobny, one of them was sunk. The handwritten history of the Black Sea Fleet squadron also insists on the sinking of the torpedo boat. According to post-war data, the fact of the destruction of the torpedo boat has not been confirmed. G.P. is silent about this in his report. Bad luck. A number of publications on the events of October 6 speak not only about the sinking of the boat, but about the damage to two more enemy boats. How, with two enemy units discovered, it was possible to sink one and damage two, it is completely incomprehensible... If the discovered ships were indeed German torpedo boats S-28, S-42, S-45, then at best they could only be damaged, since all these three boats subsequently actively participated in hostilities in the Black Sea.

From the combat log of the operational duty headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet: “05 hours 40 minutes. Single enemy aircraft search for ships and drop bombs. When approaching Feodosia, the ships encountered strong enemy resistance: coastal artillery, TKATKA (torpedo boats - V.Sh.

) and enemy aircraft that counteracted the shelling of the port.”

The political report noted that as many as five consecutive attacks were carried out on the detachment’s ships by enemy torpedo boats. Five torpedo attacks carried out by two or even three boats! But this means that the destroyers in this case fought a fairly long battle: after all, at least two of the three boats in this case had to carry out two attacks, and this would have taken some time. As for the report of G.P. Bad luck, he only writes about one attack.

In general, in this episode our destroyers acted quite successfully. Firstly, the boats were discovered at a sufficient distance. Secondly, the destroyers performed an evasive maneuver to avoid torpedoes from torpedo boats. This was the first and last successful maneuver in the entire war to evade torpedoes from torpedo boats. Thirdly, the destroyers managed to achieve an artillery hit on a German boat. Let alone, but still!

* * *

Meanwhile, the leader of “Kharkov” approached Yalta at 6 o’clock in the morning and, from a distance of 70 cables, fired at the port with 104 high-explosive 130-mm shells. There is also one unclear point here. Let us remember that, according to the plan of the raid operation, the firing of our ships at enemy ports was to be corrected by two aircraft - DB-3 and Pe-2 - under the cover of four fighters. In addition, 6 more aircraft (4 Il-2 and 2 B-3) “were supposed to suppress the enemy’s advanced batteries in the event of their opposition.” But there were no planes of ours over the ports when the ships approached them. At least, there is not the slightest mention of them in any document. Why? I haven't found the answer to this question anywhere. Did all these planes die, were damaged, or were simply driven away by enemy aircraft, or maybe for some reason they were not sent at all? In the latter case, the entire planned operation turned into a criminal farce in advance. It is difficult to expect real results when shooting at night in areas of a darkened port without adjustments.

Our side never officially reports how successful the leader's shooting was. The Germans, on the contrary, write, not without gloating, that as a result of the Kharkov firing at Yalta, several private houses were destroyed there and several local residents were killed. This means that the shooting was completely ineffective.

Looking through the case of the sinking of the Kharkov leader in the FSB archive, I came across a filed intelligence report from Yalta, in which the German data were generally confirmed.

After 13 minutes, “Kharkov” stopped firing, but immediately came under return fire from a 3-gun coastal battery from Cape Aytodor. The shells of this battery, however, landed with large undershoots. In response, "Kharkov" fired 32 shells.

At 6:35 a.m., “Kharkov” was fired upon by a 5-gun, 6-inch battery located south of Alushta. And her shells landed with large undershoots. In both cases, the leader responded to the batteries from the stern guns, but this time the hits were recorded in the target area. Soon the enemy battery fell silent, either from the damage inflicted, or because the leader left the zone of its fire.

From the combat log of the operational duty headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet: “05 hours 25 minutes. To cover the ships, a flight of Kittyhawk aircraft was sent from Gelendzhik, which at 06:04. discovered the EM "Besposhchadny" and EM "Sposobny". Continuous patrolling of the IA over the ships began. 06 h. 10 min. "EMEM stopped performing the task and began to retreat on a course of 240 degrees to approach the Kharkov LD, which was located west of EMEM." In the “Note” column it is written: “Report to. 2 r. Mischief and testimony of the crews covering the ships."

At 07:05 in the OD database log of the Black Sea Fleet headquarters there are two entries at once. The first of them reads: “As a result of the morning battle, the Sposobny EM sank the enemy’s TKA. The ships have no damage." This inscription has been erased with an eraser, but you can still make it out. Maybe it was this erroneous entry that was the starting point in the story of the sunken boat? Immediately after the erased inscription there is another: “07 h. 05 min. An enemy reconnaissance aircraft appeared over the Kharkov LD, located in square 1571. At the same time, EMEM fired at 6 enemy infantry bases (?) going from Yalta to Feodosia.” In the “Note” column opposite this entry it reads: “Report to. 2 r. Bad things."

At 7:10 a.m., at a heading angle of 10–15 degrees on the starboard side of the destroyer “Besposhchadny,” the leader “Kharkov” was discovered at a distance of 90 cables. The political report noted that the meeting of the ships took place at 7:05 am.

From the combat log of the operational duty headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet: “07 hours 30 minutes. Our reconnaissance aircraft observed several fires in the port of Yalta and in the western part of the city. The port was shrouded in smoke from the fire. This was the result of the shelling of the port by the LD Kharkov, which fired 100 shells at the port.”

From the combat log of the operational duty headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet: “07 hours 30 minutes. EMEM position: W = 44 degrees 29 minutes, L = 35 degrees 05 minutes, course - 115 degrees, speed 24 knots." In the “Note” it is written: “Report of Negoda.”

From the interrogation on December 22, 1943, as a witness of the commander of the warhead-1 destroyer “Besposhchadny” N.Ya. Glazunov: “We arrived at the place of shelling at about 5 o’clock in the morning with minutes to spare. There our ships were met by active attacks by boats, shelling of coastal batteries and aircraft. The situation for the ships became critical. A few minutes later, having abandoned the task, “Besposhchadny” and “Sposobny” went to the junction point with “Kharkov”. I consider it necessary to note that the designated junction of all ships put them at an extremely disadvantageous position in relation to enemy aircraft. First of all, this unfavorable condition was that the connection point was in the Alushta region near the coastline, about 10-18 miles, and at 7:20 a.m. it was already full dawn.”

From the interrogation as a witness of the division mechanic of the 1st destroyer division G.A. Vitsky: “On the morning of October 4, the ships arrived in Tuapse, where they stayed for 36 hours. The officers learned about the tasks and nature of the operation when the ships were already at sea. In accordance with the operation plan, at 6 o’clock “Kharkov” was supposed to approach Yalta. We fired 100 shots. “Kharkov” completed its task. There was no resistance from the enemy. As the Kharkov retreated, it fired an additional 30 shots at Alushta, as enemy coastal batteries were discovered. According to the operation plan, at 8 o’clock “Kharkov” was supposed to follow with “Merciless” and “Sposobny”, which was done. All three ships moved on together..."

* * *

When the whole detachment was assembled, G.P. Negoda, without wasting time, ordered the withdrawal from the Crimean shores. The ships set a speed of 24 knots and set a course of 115 degrees. A tight wave rushed from the stems. Foamy breakers foamed astern. Now it was necessary to quickly get as far as possible from the coast in order to get lost in the vastness of the sea and avoid air pursuit.

From the interrogation report on December 21, 1943 of the commander of the destroyer “Besposhchadny” V.A. Parkhomenko: “My assumptions (previously, during interrogation, V.A. Parkhomenko testified that he believed that after the Germans discovered ships approaching Crimea, they should have immediately abandoned the continuation of the operation . - V.Sh.

) turned out to be correct, and when we began to approach Feodosia to shell the port, we were met by torpedo boats and coastal batteries. Having encountered such serious resistance from the enemy (we were also bombed by enemy planes), Divisional Commander Negoda abandoned the assigned task and ordered to go to the rendezvous point with the Kharkov. After the meeting with Kharkov, we began to retreat to the base. Already at dawn, our aircraft began to cover us.”

From the interrogation on December 22, 1943, as a witness of the commander of the warhead-1 destroyer “Besposhchadny” N.Ya. Glazunova: “Question: Did the meeting with Kharkov take place at the appointed place and at the appointed time?

Answer: Yes.

Question: What was the speed of the ships when leaving the coast?

Answer: After connecting on departure, the ships had a speed of 24 knots.

Question: Could you do more?

Answer: They could depart at least 30 knots.

Question: Why didn’t they increase the speed?

Answer: I can only assume there was complacency, which was reinforced by the fact that previous operations took place without any manifestation of enemy activity."

From the protocol of interrogation on December 22, 1943, as a witness of the former commander of the BC-1 destroyer “Sposobny” (at the time of interrogation, the commander of the BC-1 destroyer “Bodry”), senior lieutenant L.L. Kostrzewski: “Question: Did they fulfill the task that the ships had?

Answer: No. The destroyers did not complete the task, the ships were unable to shell the port, because they were attacked by enemy aircraft and boats. The ships limited themselves to attacking the latter.

Question: How did the division command make the decision to refuse to complete the mission, the movement of the ships, what was the direction?

Answer: After the attacks of the enemy boats were repulsed, the ships moved about 10-12 miles out to sea. From where the ships were already moving to the connection point with Kharkov. The connection with the Kharkov occurred approximately at the time envisaged during the operation, and the ships set on the course envisaged by the course of the operation.

Question: In what area did the ships gather?

Answer: In the Alushta area, 7–8 miles from the coast.

Question: What time?

Answer: At approximately 7:15 a.m. the ships set out on their departure course.

Question: What speed did the ships have?

Answer: The ships had a speed of 30 knots.

Question: Was this their maximum move?

Answer: No, this move is not the maximum. This speed was provided for by the operation schedule.”

* * *

While the ships are leaving the Crimean coast at full speed, let’s find out how the Black Sea Fleet’s aviation operated in the skies over Feodosia.

At 24:00 on October 5, the commander of the 1st Mine-Torpedo Aviation Division gave the order to load bombs onto the planes and prepare them for final departure. The pilots were informed of the flight routes, targets and strike times. Due to the fact that the combat mission was set by the Air Force command literally at the last moment, and there was no longer time to work out all the necessary documents, the planned table of combat operations was adopted as the main document, according to which, at one in the morning on October 6, the combat mission was assigned to the command of the regiments and airplanes.

At 3 hours 20 minutes, the division commander received a new order - the bombers assigned to suppress artillery batteries in Feodosia should be urgently redirected to suppress batteries at Cape Kiik-Atalma. Cover the ships with three shifts of Kittyhawk fighters. According to the weather service, the weather is clear along the route and in the target area.

The first to take off at 4 hours 00 minutes was the Il-4 of Senior Lieutenant Kitsenko (navigator Senior Lieutenant Kopenko), who had the task of reconnaissance of the target using SAB flare bombs and adjusting the fire of the destroyers on the target. At 4 hours 45 minutes (i.e. half an hour before the start of shooting), the pilots began to call the ships via communications, but they did not answer. Already approaching the target, a malfunction of the transmitter was discovered. The malfunction was resolved by 5 hours 40 minutes. At 5 hours 10 minutes, the IL-4 reached the target and remained above it until 6 hours 5 minutes. But even after repairing the damage to the transmitter, the ships still did not communicate. At 5 hours 20 minutes, IL-4 dropped 10 SABs from an altitude of 2600 meters in order to consecrate the Feodosia port and raid. At the same time, no watercraft were observed from the plane in the port or roadstead. At 5:20 a.m., the plane saw bursts of artillery fire from the destroyers and it stopped by 6 a.m. According to the pilots, shell explosions were noted mainly in the area of the railway tracks northwest of the pier and the station. At 6:50 a.m. the plane landed at the airfield. According to the command, the aircraft did not fully complete its combat mission.

The second Il-4 of the Guard, Captain Lobanov (navigator of the Guard, Junior Lieutenant Basalkevich), which had the task of suppressing coastal artillery batteries at Cape Kiik-Atlama and Koktebel, took off simultaneously with the first plane at 4 o’clock. From 5 hours 30 minutes to 5 hours 48 minutes, the plane bombed a German artillery battery in Koktebel in two passes from an altitude of 4000 meters, while 6 FAB-100 bombs were dropped on the battery. The pilots observed bomb explosions at the battery location. At the same time, the battery at Cape Kiik-Atlama fired very weakly. As for the battery in Koktebel, on the contrary, it fired very intensely, and after the bombing it never stopped firing. Having been bombed, the plane returned to the airfield at 6:45 am.

The third Il-4 of the Guard, senior lieutenant Kragun (navigator of the guard, junior lieutenant Prokopchuk) took off at 4 hours 02 minutes, having the same task as the previous plane. From 5 hours 38 minutes to 5 hours 52 minutes, the plane bombed an artillery battery on Cape Kiik-Atlama from an altitude of 4000 meters in two passes, dropping 5 FAB-100 bombs. Explosions of the pilot's bombs were observed at the battery location. During the second bombing run, the Il-4 crew noticed that the battery located in Koktebel was firing intensely at our ships. Therefore, this battery was also bombed in two passes and another 5 FAB-100s were dropped. After the second approach, the battery stopped firing. Anti-aircraft guns from Cape Kiik-Atlama and Feodosia fired at the planes bombing the batteries, and they tried to “grope” the planes from the port with a searchlight. In addition, the pilots also observed a German fighter, which, however, did not make any attacks. While carrying out bombing strikes, the pilots established that the German battery installed west of Cape Kiik-Atlama had two guns, and the battery in Koktebel had four.