The fate of military equipment (including warships) does not always turn out the way its creators saw it. Sometimes this is not even related to the level of technical characteristics - but only to external circumstances. Russian patrol ships of Project 11540 Yastreb unwittingly became “victims” of such circumstances.

It is difficult to call these frigates “unsuccessful” or “obsolete.” The lead ship of the project, Neustrashimy, was even a “celebrity” at one time—the media covered the details of its fight against pirates. But the Hawks were unable to replace their predecessors or even take an important place in the Russian fleet.

History and design

One of the most numerous ocean-going ships in the Soviet navy were the Project 1135 patrol ships. This type of frigate was developed back in the 60s, and since 1970 more than 40 ships have been built. Of course, the command foresaw the need to develop new patrol aircraft. Project 1135 was developed for already outdated weapons, usually heavier and bulkier than the newest ones. There was no helipad at the TFR.

The first versions of the project for the future "Hawk" were worked out already in 1975. Six years later, the construction of Project 11540 patrol ships was included in the next five-year plan. Initially, it was expected that the lead ship would enter service in 1986, but constant refinement of the project led to the fact that in 1987 it was only possible to begin laying the ship. The Hawks were to be built in Kaliningrad.

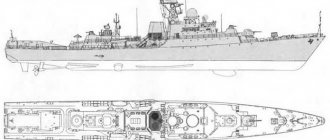

Project 11540 frigates have a steel hull with a long forecastle, divided into 12 watertight compartments.

The original design suggested using light alloys in the design, but analysis of the Falklands War led to the abandonment of this solution.

Traditionally, the Soviet Navy used superstructures with beveled edges and inclined surfaces to reduce radar signature. On the Yastreby, in order to maximize the use of internal volumes, this solution was abandoned, but the superstructures received characteristic kinks in the form of corrugation.

The power plant consists of 2 sustainer gas turbines M-70 and 2 afterburner M-90. Each pair of turbines under normal conditions rotates one shaft out of two, but in principle each engine has the ability to operate on two shafts. In the event of turbine failure, the ship's systems provide electricity to 2 diesel generators. To improve seaworthiness and habitability, the Hawks have pitch stabilizers and side keels. At the same time, the densest layout still led to cramped living quarters.

Construction[ | ]

The ship's hull is a forecastle, with an extended forecastle and a bow bulb, in which the antenna of the hydroacoustic complex is located, there are two masts and two chimneys.

The hull is divided into 12 compartments by waterproof bulkheads. Both the hull and superstructure are made entirely of steel, created using technologies to reduce acoustic signature. The ship is equipped with pitch stabilizers, as well as bilge keels, which help improve seaworthiness.

Devices are provided for receiving liquid and dry cargo from supply vessels at sea.

Armament

On the forecastle of the frigates there is an AK-100 artillery mount of 100 mm caliber. The artillery system has a high (up to 60 rounds per minute) rate of fire and is guided by radar. The installation is universal; shells with radio fuses are used to destroy air targets.

The main anti-aircraft weapons are the Kinzhal missiles, the launch silos of which are also located on the forecastle.

The complex allows launches against 4 targets simultaneously. Auxiliary air defense means - 2 Kortik missile and gun installations located at the stern. Each installation includes a 30 mm AO-18 cannon and 2 containers with 4 missiles, similar to those used on the Tunguska self-propelled gun.

To combat underwater targets, Project 11540 patrol ships received, firstly, Vodopad missile-torpedoes launched from standard tube torpedo tubes. Secondly, RBU-6000 bomb launchers, capable of not only hitting submarines with bombs, but also “intercepting” torpedoes threatening the ship. Finally, anti-submarine missions are carried out by the ship-based Ka-27 helicopter.

But the Hawks were out of luck with the main anti-ship weapon. According to the plan, they were supposed to be Uran missiles, developed on the basis of the X-35 aircraft anti-ship missiles. However, Neustrashimy never received them. The second frigate, Yaroslav the Mudry, was equipped with launch containers along its sides only in 2014.

On the main mast of the ships there is an MP-755 radar antenna with two phased arrays. The radar of the MP-352 anti-aircraft complex uses an antenna mounted on the foremast. The patrol boats are equipped with satellite navigation and the Tron combat information and control system.

Content

- 1 Same type ships

- 2 Construction

- 3 Construction

- 4 Armament 4.1 Anti-submarine weapons

- 4.2 Air defense systems

- 4.3 Artillery

- 4.4 Other

- 4.5 Aviation

- 4.6 Missile weapons

- 6.1 Awards

Exploitation

In the last years of the existence of the USSR, three ships of the project were laid down in Kaliningrad - Neustrashimy, Impregnable and Tuman. Only Neustrashimy managed to complete construction and commissioning. The construction of his “sisterships” has actually stopped.

Only after some improvement in the economic situation, in 2003, it was decided to complete the construction of the second ship, which by this time had changed its name.

For some reason, the “traditional” name “Unapproachable” was changed to the name of a prince who had nothing to do with sea voyages. Completion dragged on for several years, and only in 2009 (20 years after its laying) “Yaroslav the Wise” entered combat formation.

“Fog” was the least fortunate of all. They tried to interest foreign buyers with this frigate; they even prepared a completion project according to a modified, “export” project. However, there were no buyers. After the completion of the Yaroslav the Wise, they also did not begin to work on the Fog, saying that another frigate “does not fit into the development strategy” and therefore is simply not needed. It was reported that in 2016 they decided to dispose of the Tuman hull.

In 2008, the Neustrashimy received its share of world fame - it was sent to patrol off the coast of Somalia to protect merchant ships from pirates. There he used weapons at least three times, repelling pirate attacks. In 2010 and 2013, combat duty in the Gulf of Aden continued. The patrol ship is currently undergoing repairs. In 2016, “Yaroslav the Wise” also set out to fight pirates, but by this time their activity had decreased, and this campaign did not receive such wide coverage in the media.

Same type ships[ | ]

On June 19, 2009, the second ship of this type, SKR 727 “Yaroslav the Mudry”, built at the Baltic Shipbuilding Plant, was transferred to the Russian Navy[1]. In 2010, Yantar offered the Customer to use the reserves for the third building (47% complete) for the construction of the Tuman complex. It was assumed that in 2012, the Neustrashimy TFR and the Yaroslav the Mudry TFR might be relocated to the Black Sea Fleet after agreeing on this issue with Ukraine and would be oriented by the Black Sea Fleet command to maintain the operational regime in the fleet’s area of responsibility - the Black and Mediterranean Seas.

Specifications

American ships of the Oliver Perry type can be considered an analogue of Project 11540 frigates, although they began to be built earlier.

| Project 11540 "Hawk" | FFG-7 Oliver H. Perry | |

| Length, m | 129 | 135 |

| Displacement, t | 4350 | 4200 |

| Travel speed, knots | 30 | 29 |

| Armament | 100 mm AU, SAM "Dagger", SAM "Kortik", anti-ship missile system "Uran", RBU-6000, RPK "Vodopad" | 76 mm AU, 20 mm AU, Standard air defense missile system, Harpoon anti-ship missile system, 2 torpedo tubes |

| Cruising range, miles | 3500 | 5000 |

| Crew | 214 | 219 |

The American frigates were intended to provide air defense and anti-aircraft defense on long voyages, for which they were equipped with long-range Standard anti-aircraft missiles and carried two anti-submarine helicopters (instead of one on the Hawks). This also explains the increased cruising range compared to Soviet and Russian ships.

Currently, American frigates are considered obsolete. Almost all ships have been decommissioned or sold.

For more than 20 years, Neustrashimy would be the only Yastreb in service.

And by the time Yaroslav the Wise was completed, it turned out that 11540 had already become obsolete.

Now the future of the Russian fleet is associated with new frigates - Project 22350. The Hawks retained the role of ships that helped survive the “transition period”.

Ship commanders[ | ]

- captain 3rd rank Kolyakov Igor Arkadyevich (June 29, 1990—February 23, 1991)[20]

- captain 2nd rank Avraamov Nikolai Georgievich (February 23, 1991—May 13, 1993)[20]

- captain 2nd rank Ryzhkov Igor Georgievich (May 13, 1993—July 4, 1996)[20]

- captain 3rd rank Demidovich Igor Dmitrievich (July 4, 1996-1998)[20]

- captain 3rd rank Yasnitsky Pavel Gennadievich (1998—2002)[20]

- captain 2nd rank Kutyshenko Pavel Anatolyevich (2002-2004)

- captain 2nd rank Smirnov Igor Nikolaevich (2004—2007)

- captain 2nd rank Apanovich Alexey Vasilievich (2007—2010)

- captain 2nd rank Baranov Denis Valerievich (2010—2012)

- captain 2nd rank Ashurov Roman Yurievich (2012-2013)

- Captain-Lieutenant Suslov Alexey Grigorievich (2013—2013)

- captain 2nd rank Lipsky Sergey Aleksandrovich (2013—2013)

- captain 3rd rank Ovsyannikov Evgeniy Aleksandrovich (2013—2016)

- captain 3rd rank Naumov Vladimir Aleksandrovich (2017—2019)

- captain 3rd rank Somov Yuri Nikolaevich (since 2022)[20]

An excerpt characterizing the Neustrashimy (patrol ship)

“I know that no one can help unless nature helps,” said Prince Andrei, apparently embarrassed. – I agree that out of a million cases, one is unfortunate, but this is her and my imagination. They told her, she saw it in a dream, and she is afraid. “Hm... hm...” the old prince said to himself, continuing to write. - I'll do it. He drew out the signature, suddenly turned quickly to his son and laughed. - It's bad, huh? - What's bad, father? - Wife! – the old prince said briefly and significantly. “I don’t understand,” said Prince Andrei. “There’s nothing to do, my friend,” said the prince, “they’re all like that, you won’t get married.” Do not be afraid; I won't tell anyone; and you know it yourself. He grabbed his hand with his bony little hand, shook it, looked straight into his son’s face with his quick eyes, which seemed to see right through the man, and laughed again with his cold laugh. The son sighed, admitting with this sigh that his father understood him. The old man, continuing to fold and print letters, with his usual speed, grabbed and threw sealing wax, seal and paper. - What to do? Beautiful! I'll do everything. “Be at peace,” he said abruptly while typing. Andrei was silent: he was both pleased and unpleasant that his father understood him. The old man stood up and handed the letter to his son. “Listen,” he said, “don’t worry about your wife: what can be done will be done.” Now listen: give the letter to Mikhail Ilarionovich. I am writing to tell him to use you in good places and not keep you as an adjutant for a long time: it’s a bad position! Tell him that I remember him and love him. Yes, write how he will receive you. If you are good, serve. Nikolai Andreich Bolkonsky’s son will not serve anyone out of mercy. Well, now come here. He spoke in such a rapid-fire manner that he did not finish half the words, but his son got used to understanding him. He led his son to the bureau, threw back the lid, pulled out the drawer and took out a notebook covered in his large, long and condensed handwriting. “I must die before you.” Know that my notes are here, to be handed over to the Emperor after my death. Now here is a pawn ticket and a letter: this is a prize for the one who writes the history of Suvorov’s wars. Send to the academy. Here are my remarks, after me read for yourself, you will find benefit. Andrei did not tell his father that he would probably live for a long time. He understood that there was no need to say this. “I will do everything, father,” he said. - Well, now goodbye! “He let his son kiss his hand and hugged him. “Remember one thing, Prince Andrei: if they kill you, it will hurt my old man...” He suddenly fell silent and suddenly continued in a loud voice: “and if I find out that you did not behave like the son of Nikolai Bolkonsky, I will be ... ashamed!” – he squealed. “You don’t have to tell me this, father,” the son said, smiling. The old man fell silent. “I also wanted to ask you,” continued Prince Andrey, “if they kill me and if I have a son, do not let him go from you, as I told you yesterday, so that he can grow up with you... please.” - Shouldn’t I give it to my wife? - said the old man and laughed. They stood silently opposite each other. The old man's quick eyes were directly fixed on his son's eyes. Something trembled in the lower part of the old prince’s face. - Goodbye... go! - he suddenly said. - Go! - he shouted in an angry and loud voice, opening the office door. - What is it, what? - asked the princess and princess, seeing Prince Andrei and for a moment the figure of an old man in a white robe, without a wig and wearing old man’s glasses, leaning out for a moment, shouting in an angry voice. Prince Andrei sighed and did not answer. “Well,” he said, turning to his wife. And this “well” sounded like a cold mockery, as if he was saying: “Now do your tricks.” – Andre, deja! [Andrey, already!] - said the little princess, turning pale and looking at her husband with fear. He hugged her. She screamed and fell unconscious on his shoulder. He carefully moved away the shoulder on which she was lying, looked into her face and carefully sat her down on a chair. “Adieu, Marieie, [Goodbye, Masha,”] he said quietly to his sister, kissed her hand in hand and quickly walked out of the room. The princess was lying in a chair, M lle Burien was rubbing her temples. Princess Marya, supporting her daughter-in-law, with tear-stained beautiful eyes, still looked at the door through which Prince Andrei came out, and baptized him. From the office one could hear, like gunshots, the often repeated angry sounds of an old man blowing his nose. As soon as Prince Andrei left, the office door quickly opened and the stern figure of an old man in a white robe looked out. - Left? Well, good! - he said, looking angrily at the emotionless little princess, shook his head reproachfully and slammed the door. In October 1805, Russian troops occupied the villages and towns of the Archduchy of Austria, and more new regiments came from Russia and, burdening the residents with billeting, were stationed at the Braunau fortress. The main apartment of Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov was in Braunau. On October 11, 1805, one of the infantry regiments that had just arrived at Braunau, awaiting inspection by the commander-in-chief, stood half a mile from the city. Despite the non-Russian terrain and situation (orchards, stone fences, tiled roofs, mountains visible in the distance), despite the non-Russian people looking at the soldiers with curiosity, the regiment had exactly the same appearance as any Russian regiment had when preparing for a review somewhere in the middle of Russia. In the evening, on the last march, an order was received that the commander-in-chief would inspect the regiment on the march. Although the words of the order seemed unclear to the regimental commander, and the question arose how to understand the words of the order: in marching uniform or not? In the council of battalion commanders, it was decided to present the regiment in full dress uniform on the grounds that it is always better to bow than not to bow. And the soldiers, after a thirty-mile march, did not sleep a wink, they repaired and cleaned themselves all night; adjutants and company commanders counted and expelled; and by morning the regiment, instead of the sprawling, disorderly crowd that it had been the day before during the last march, represented an orderly mass of 2,000 people, each of whom knew his place, his job, and of whom, on each of them, every button and strap was in its place and sparkled with cleanliness . Not only was the outside in good order, but if the commander-in-chief had wanted to look under the uniforms, he would have seen an equally clean shirt on each one and in each knapsack he would have found the legal number of things, “sweat and soap,” as the soldiers say. There was only one circumstance about which no one could be calm. It was shoes. More than half the people's boots were broken. But this deficiency was not due to the fault of the regimental commander, since, despite repeated demands, the goods were not released to him from the Austrian department, and the regiment traveled a thousand miles. The regimental commander was an elderly, sanguine general with graying eyebrows and sideburns, thick-set and wider from chest to back than from one shoulder to the other. He was wearing a new, brand new uniform with wrinkled folds and thick golden epaulettes, which seemed to lift his fat shoulders upward rather than downward. The regimental commander had the appearance of a man happily performing one of the most solemn affairs of life. He walked in front of the front and, as he walked, trembled at every step, slightly arching his back. It was clear that the regimental commander was admiring his regiment, happy with it, that all his mental strength was occupied only with the regiment; but, despite the fact that his trembling gait seemed to say that, in addition to military interests, the interests of social life and the female sex occupied a significant place in his soul. “Well, Father Mikhailo Mitrich,” he turned to one battalion commander (the battalion commander leaned forward smiling; it was clear that they were happy), “it was a lot of trouble this night.” However, it seems that nothing is wrong, the regiment is not bad... Eh? The battalion commander understood the funny irony and laughed. - And in Tsaritsyn Meadow they wouldn’t have driven you away from the field. - What? - said the commander. At this time, along the road from the city, along which the makhalnye were placed, two horsemen appeared. These were the adjutant and the Cossack riding behind. The adjutant was sent from the main headquarters to confirm to the regimental commander what was said unclearly in yesterday's order, namely, that the commander-in-chief wanted to see the regiment exactly in the position in which it was marching - in overcoats, in covers and without any preparations. A member of the Gofkriegsrat from Vienna arrived to Kutuzov the day before, with proposals and demands to join the army of Archduke Ferdinand and Mack as soon as possible, and Kutuzov, not considering this connection beneficial, among other evidence in favor of his opinion, intended to show the Austrian general that sad situation , in which troops came from Russia. For this purpose, he wanted to go out to meet the regiment, so the worse the situation of the regiment, the more pleasant it would be for the commander-in-chief. Although the adjutant did not know these details, he conveyed to the regimental commander the commander-in-chief’s indispensable requirement that the people wear overcoats and covers, and that otherwise the commander-in-chief would be dissatisfied. Having heard these words, the regimental commander lowered his head, silently raised his shoulders and spread his hands with a sanguine gesture. - We've done things! - he said. “I told you, Mikhailo Mitrich, that on a campaign, we wear greatcoats,” he turned reproachfully to the battalion commander. - Oh, my God! - he added and decisively stepped forward. - Gentlemen, company commanders! – he shouted in a voice familiar to the command. - Sergeants major!... Will they be here soon? - he turned to the arriving adjutant with an expression of respectful courtesy, apparently referring to the person about whom he was speaking. - In an hour, I think. - Will we have time to change clothes? - I don’t know, general... The regimental commander, himself approaching the ranks, ordered that they change into their overcoats again. The company commanders scattered to their companies, the sergeants began to fuss (the overcoats were not entirely in good working order) and at the same moment the previously regular, silent quadrangles swayed, stretched out, and hummed with conversation. Soldiers ran and ran up from all sides, threw them from behind with their shoulders, dragged backpacks over their heads, took off their greatcoats and, raising their arms high, pulled them into their sleeves. Half an hour later everything returned to its previous order, only the quadrangles turned gray from black. The regimental commander, again with a trembling gait, stepped forward of the regiment and looked at it from afar. - What else is this? What's this! – he shouted, stopping. - Commander of the 3rd company!.. - Commander of the 3rd company to the general! commander to the general, 3rd company to the commander!... - voices were heard along the ranks, and the adjutant ran to look for the hesitant officer. When the sounds of diligent voices, misinterpreting, shouting “general to the 3rd company”, reached their destination, the required officer appeared from behind the company and, although the man was already elderly and did not have the habit of running, awkwardly clinging to his toes, trotted towards the general. The captain's face expressed the anxiety of a schoolboy who is told to tell a lesson he has not learned. There were spots on his red (obviously from intemperance) nose, and his mouth could not find a position. The regimental commander examined the captain from head to toe as he approached breathlessly, slowing his pace as he approached. – You’ll soon dress people up in sundresses! What's this? - shouted the regimental commander, extending his lower jaw and pointing in the ranks of the 3rd company to a soldier in an overcoat the color of factory cloth, different from other overcoats. - Where were you? The commander-in-chief is expected, and you are moving away from your place? Eh?... I'll teach you how to dress people in Cossacks for a parade!... Eh?... The company commander, without taking his eyes off the commander, pressed his two fingers more and more to the visor, as if in this one pressing he now saw his salvation . - Well, why are you silent? Who's dressed up as a Hungarian? – the regimental commander joked sternly. – Your Excellency... – Well, what about “Your Excellency”? Your Excellency! Your Excellency! And what about Your Excellency, no one knows. “Your Excellency, this is Dolokhov, demoted...” the captain said quietly. - Was he demoted to field marshal or something, or to soldier? And a soldier must be dressed like everyone else, in uniform. “Your Excellency, you yourself allowed him to go.” - Allowed? Allowed? “You’re always like this, young people,” said the regimental commander, cooling down somewhat. - Allowed? I’ll tell you something, and you and...” The regimental commander paused. - I’ll tell you something, and you and... - What? - he said, getting irritated again. - If you please, dress the people decently... And the regimental commander, looking back at the adjutant, walked towards the regiment with his trembling gait. It was clear that he himself liked his irritation, and that, having walked around the regiment, he wanted to find another pretext for his anger. Having cut off one officer for not cleaning his badge, another for being out of line, he approached the 3rd company. - How are you standing? Where's the leg? Where's the leg? - the regimental commander shouted with an expression of suffering in his voice, still about five people short of Dolokhov, dressed in a bluish overcoat. Dolokhov slowly straightened his bent leg and looked straight into the general’s face with his bright and insolent gaze. - Why the blue overcoat? Down with... Sergeant Major! Changing his clothes... rubbish... - He didn’t have time to finish. “General, I am obliged to carry out orders, but I am not obliged to endure...” Dolokhov hastily said. “Don’t talk at the front!... Don’t talk, don’t talk!...” “You don’t have to endure insults,” Dolokhov finished loudly, resoundingly. The eyes of the general and the soldier met. The general fell silent, angrily pulling down his tight scarf. “Please change your clothes, please,” he said, walking away. - He's coming! - the makhalny shouted at this time. The regimental commander, blushing, ran up to the horse, with trembling hands took the stirrup, threw the body over, straightened himself, took out his sword and with a happy, decisive face, his mouth open to the side, prepared to shout. The regiment perked up like a recovering bird and froze. - Smir r r r na! - the regimental commander shouted in a soul-shaking voice, joyful for himself, strict in relation to the regiment and friendly in relation to the approaching commander. Along a wide, tree-lined, highwayless road, a tall blue Viennese carriage rode in a row at a brisk trot, its springs slightly rattling. Behind the carriage galloped a retinue and a convoy of Croats. Next to Kutuzov sat an Austrian general in a strange white uniform among the black Russians. The carriage stopped at the shelf. Kutuzov and the Austrian general were talking quietly about something, and Kutuzov smiled slightly, while, stepping heavily, he lowered his foot from the footrest, as if these 2,000 people were not there, who were looking at him and the regimental commander without breathing . A shout of command was heard, and again the regiment trembled with a ringing sound, putting itself on guard. In the dead silence the weak voice of the commander-in-chief was heard. The regiment barked: “We wish you good health, yours!” And again everything froze. At first, Kutuzov stood in one place while the regiment moved; then Kutuzov, next to the white general, on foot, accompanied by his retinue, began to walk along the ranks. By the way the regimental commander saluted the commander-in-chief, glaring at him with his eyes, stretching out and getting closer, how he leaned forward and followed the generals along the ranks, barely maintaining a trembling movement, how he jumped at every word and movement of the commander-in-chief, it was clear that he was fulfilling his duties subordinate with even greater pleasure than the duties of a superior. The regiment, thanks to the rigor and diligence of the regimental commander, was in excellent condition compared to others who came to Braunau at the same time. There were only 217 people who were retarded and sick. And everything was fine, except for the shoes. Kutuzov walked through the ranks, occasionally stopping and speaking a few kind words to the officers whom he knew from the Turkish war, and sometimes to the soldiers. Looking at the shoes, he sadly shook his head several times and pointed them out to the Austrian general with such an expression that he didn’t seem to blame anyone for it, but he couldn’t help but see how bad it was. Each time the regimental commander ran ahead, afraid to miss the commander-in-chief's word regarding the regiment. Behind Kutuzov, at such a distance that any faintly spoken word could be heard, walked about 20 people in his retinue. The gentlemen of the retinue talked among themselves and sometimes laughed. The handsome adjutant walked closest to the commander-in-chief. It was Prince Bolkonsky. Next to him walked his comrade Nesvitsky, a tall staff officer, extremely fat, with a kind and smiling handsome face and moist eyes; Nesvitsky could hardly restrain himself from laughing, excited by the blackish hussar officer walking next to him. The hussar officer, without smiling, without changing the expression of his fixed eyes, looked with a serious face at the back of the regimental commander and imitated his every movement. Every time the regimental commander flinched and bent forward, in exactly the same way, in exactly the same way, the hussar officer flinched and bent forward. Nesvitsky laughed and pushed others to look at the funny man.