Strategic position

November 11, 1918 was the day of the greatest triumph of the French army.

In Europe, both Germany and Russia were not its competitors in military power, and the new powers owed a lot to France and were much weaker than it. Moreover, French troops entered German territory to ensure reparations. Naturally, the first post-war plans were offensive, especially since they were supported by their faithful allies, the Belgians. But France was extremely exhausted. Losses were record high. The economy is destroyed. The country is in debt like silk. All this caused a sharp reduction in the military budget and, accordingly, the gradual obsolescence of weapons.

War-torn Lens (photo source)

Ten years after the end of the war, intelligence began to frighten the Germans with the growth of their capabilities. At the same time, they were intimidated by bomber aircraft, which the Germans were officially banned from. The intelligence opinion that the Germans would turn passenger planes into bombers and bomb Paris, although overly pessimistic, had some basis. Suffice it to say that during the friendly visit of Italian seaplanes, the latest French fighters were unable to accompany them - they were not fast enough. Moreover, French intelligence threatened a 400,000-strong Reichswehr! Allegedly, the Germans secretly managed to quadruple the Versailles restrictions.

At this point I had to wonder: weren’t the scouts consuming too much of something bohemian?

The last straw for the change in planning was the transition to a one-year service period, after which the already not very large army became completely tied to mobilization. Until it ended, the combat effectiveness of the 300,000-strong French army remained highly doubtful. There could be no talk of any offensive operations until mobilization and deployment were completed.

In addition, the most important French resources - coal and ore - were located right on the border, literally kilometers from Germany. And of course, Lorraine and Alsace bordered Germany - everything that was acquired through back-breaking labor in the First World War could immediately be under attack. After the abandonment of offensive plans, it became clear that fortifications were needed that would allow the army to calmly mobilize and deploy. These thoughts, born in the army environment, also received political support.

Europe after the First World War (photo source)

But there were also nuances that limited the desire to fill the entire border with concrete. Firstly, Belgium.

Belgium is not only many, many excellent fortresses, but also thirty divisions.

It would be a sin to lose such an ally. Therefore, it is politically incorrect to build a line of fortifications on the Franco-Belgian border - this may arouse suspicion in the ally that they are going to throw him to the mercy of the Boches. And it would be much more pleasant for the French to wage war on Belgian territory than at home - fortunately, the north of France had barely healed the wounds inflicted by the First World War.

And secondly, there was Saar. That is, France did not have it yet. Bye. But there were troops in it. And there remained hope that the Saarland (mandatory to the League of Nations) could be made French. In the thirties, a plebiscite brutally crushed these hopes, but at the time the Line was planned it was not obvious that a vote would even be held. The presence of the Saar and troops in it pushed the French to attack German territory in this direction.

History[edit]

The First World War showed that any fortification, no matter how strong, can be destroyed - you just need to hammer into this place with shells until you are blue in the face. Therefore, they moved from individual forts to distributed fortifications, when hundreds of individual small objects were installed on the battlefield in apparent disorder: firing points, bunkers, cellars, observation posts. Small size made it easier to camouflage and apply to terrain. The concrete walls withstood at least hits from 6-inch shells - the heaviest of the “massive” artillery (by the way, until now). There are few larger guns, they are cumbersome - until they are brought up, and until they manage to get into each of the hundreds of individual bunkers - how long will it take?..

This system was first used by the Germans in 1916-18 at the Metz fortress. She did not participate in the battles, but the French, who examined these fortifications after the war, honestly admitted that they were unlikely to be able to take them. The example turned out to be contagious, and almost all European countries in the interval between wars built not fortresses, but “lines”[1].

Planning

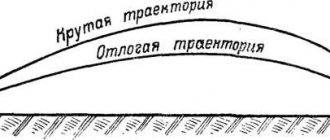

Although the Line received the name of a civilian - the Minister of War, under whom it was possible to “break through” its financing - the strategic plan was born, of course, in military circles. True, initially it was unclear whether it was worth building long-term fortifications at all, which, as the First World War showed, were quite easily destroyed by enemy artillery. As an alternative, it was planned to create a “prepared battlefield,” that is, fortifications closer to the field type, smaller in size and therefore better dispersed, which is especially important, in depth. Pétain advocated this decision.

Marshals Joffre and Weygand noted that traditionally the defense of France was built with the help of armies maneuvering near fortresses. They proposed, instead of the continuous “Great Wall of China,” to build large fortresses in important directions. The same Pétain spoke out especially vehemently against the latter, pointing to the experience of the First World War and the vulnerability of fortresses to artillery fire. As a result, we agreed on some intermediate option.

Powerful fortifications were not erected along the entire length of the border, but were concentrated in two fortified areas - near Metz and further south, in Alsace. They decided to cover the Saar gap between them, as well as the border along the Rhine, only with weaker intermediate casemates. In addition, they built somewhat weaker fortifications than the main ones in Corsica and along the Franco-Italian border.

Zamecki

The fortifications in the south were called the Alpine Line. Or the Little Maginot Line.

The forts themselves were huge structures - usually with two or three, or even a dozen combat units - armed with machine gun mounts, anti-tank and field guns, howitzers and mortars.

Their guns were protected from enemy artillery by rising towers. They could wait out the shelling in a closed state, exposing only the thick roof to enemy shells, and when the assault began, they could move up, showing the muzzles of the guns.

Much attention was paid to the supply of fortifications. We're not even talking about the famous underground narrow-gauge railway. It was common practice to create rear blocks that covered the entrance, from which fairly long underground passages stretched to the front line.

Diagram of one of the Line's fortifications from a propaganda brochure. Impressive, but far from reality.

Budget and tanks

You can often hear that the French could have spent the huge money spent on the Maginot Line much better by developing tanks and aircraft. However, this approach does not take into account many details. Firstly, the costs of the Line are high relative to the budget because the budget itself at that moment was very small. Just with the completion of the main work on the Line, expenses increased sharply - this money was spent specifically on aviation and mobile connections.

Moreover, this situation was partly programmed. In the early 30s, a depression was raging in Europe and there was no time for war.

If you spend money on tanks and aircraft, then they, as the most rapidly developing branches of the military, may become obsolete (and they will become obsolete, as practice has shown).

The fortifications will not become obsolete so quickly. This argument was also used in the debate. In addition, the tank forces, as well as the aviation, simply did not have suitable materiel that would not be embarrassing to put into production. But French military engineers produced very advanced examples of fortifications.

Czech Maginot Line

Each state cares about protecting its borders, and fortification occupies an important place in this matter. The emergence of improved types of weapons, huge armies, new forms and methods of warfare - all this influenced the development of fortification, in which a real revolution took place in the 20th century. States gripped by “fortification fever” allocated huge funds for the construction of fortifications. Czechoslovakia did not stand aside either. What she did in this regard and how the fate of the fortifications of this state turned out is in the material of our reader.

Prologue

The First World War forced us to reconsider the usual fortification concept. Military engineers came to the conclusion that isolated and closed forts and individual fortresses, which in the past served as reliable centers of defense, under new conditions do not live up to the hopes placed on them. They quickly ran out of ammunition and provisions, and the garrisons suffered losses. The essence of the new concept was the construction of many branched positions. It was believed that such fortifications were difficult to detect and even more difficult to destroy. The experience of trench warfare also made itself felt. The use of heavy artillery raised the question of building concrete and reinforced concrete structures at the positions. This is how the idea of fortification lines covering the borders appeared. The total length of such lines could range from 50 to 5000 km. They were based on URs - fortified areas. In the twentieth century, most European countries began the construction of fortifications and fortification lines.

LO vzor 37 A-160.

Orlicke Mountains, Sudetes, Czech Republic In Belgium, Poland, the USSR and France, the construction of the first fortifications began in 1928. In Europe, the Maginot Line (France), the Alpine Wall (Italy), the Stalin and Molotov Lines (USSR), and the Siegfried Line (Germany) appeared.

Why build fortifications?

The collapse of the powerful Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 radically changed the map of Europe. New states began to emerge: Hungary, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Austria, Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia. Among them was the First Czechoslovak Republic, proclaimed in Prague on October 28, 1918.

For some time it was an economically developed country, ranking tenth in the world in terms of industrial production. However, in the early 1930s, Czechoslovakia was hit by an economic crisis. The economic regression was most acutely felt in the border regions. These territories were inhabited by national minorities, most of whom - in particular the Germans - listened with interest to German propaganda. Czechoslovakia had difficult relations with Hungary, Poland and Austria. Czechoslovak Foreign Minister Edvard Benes had high hopes for the League of Nations, which, in his opinion, could resolve the state's territorial problems with its aggressive neighbors. In 1932, he drew the attention of the Minister of National Defense Bohumir Bradac and the Chief of Staff of the Army Jan Syrovia to the fact that a real threat of military conflict could arise. The Little Entente did not guarantee the Czechs protection from German expansion, so the country needed a strong ally. The Czechoslovak government searched for him for a long time, concluding various agreements with Yugoslavia, Romania and the USSR. However, after the Nazis came to power in Germany and destabilized the situation on the western borders, the government decided to take a different route and build a powerful fortification system on the border with Germany and other countries.

10.8 billion crowns were allocated for the construction of fortifications. However, they were not the only ones who had to prevent a German attack. Enormous amounts of money were spent on the army and its rearmament. In 1938, half of the state budget was allocated to modernizing the armed forces.

For Czechoslovakia, the construction of fortifications was a new and promising undertaking. The order of equipment and construction materials made it possible to attract a large part of the population to work in enterprises and in the military industry affected by the recent economic crisis. From the point of view of strategic defense, Czechoslovakia was in an extremely difficult situation. The length of its borders was 4098 km, and building a continuous fortified strip of such length was a difficult task.

Czechoslovak fortification on a German postcard from 1939

Another problem was the lack of the number of divisions necessary for a successful defense. With the available material and human resources, it was almost impossible to create a modern army. According to military experts, between the Oder and Ústí nad Labem, in an area of 400 km, the enemy could deploy about 35 divisions. To defend this area, the army had to field at least 25 divisions. The defense of a 330 km long fortification line required 45,000 men plus two divisions for the defense of the Giant Mountains and the Jesenik region. To protect the border with Germany alone, 90–110 divisions were needed on the first line, while in 1938 Czechoslovakia had only 26 formations: 2 million personnel supported by 1,582 aircraft, 469 tanks and 5,700 guns of various calibers. An extensive network of roads made it possible to quickly deploy troops and mobilize, but even this factor could not change the overall situation. A possible strike in the Klodz Valley-Brno-Mikulov direction could cut the country into two parts.

In this regard, it was decided to build fortifications that protected the country in the following areas:

- Opole–Moravian Gate–Moravian Valley;

- Klodz Valley–Brno;

- Klodz Valley–Prague;

- Walbrzych–Prague.

Fortification plans and start of construction

To build the fortifications, on December 12, 1934, the ROP (Ředitelství opevňovacích prací - Directorate of Fortification Works) adopted the first fortification program. It provided for the construction of heavy fortifications in five stages from the Oder to the Elbe. The work was camouflaged as much as possible, which was not an easy task given the large German population. Maps of the area, postcards, and magazines on which the location of structures could be marked were withdrawn from sale. In some areas, a ban on drawing and photography was introduced.

The second fortification program was approved on June 5, 1936. It provided for the construction of powerful fortified lines, this time divided into four stages. There was also a drawback: all forces had to be located in fortifications, and there were no resources left for mobile troops at all.

The third program was approved on November 9, 1937 by the head of the ROP, Karl Husarek. He proposed a plan for the construction of two strips of light fortifications of the vz.37 type along the entire length of the northern border. It was planned to cover the most vulnerable areas with a reinforced line of heavy structures. It was assumed that all work would be completed by the end of 1951. Over 15 years, it was planned to build 1,276 heavy and 15,463 light objects. In the sector between the Oder and the Elbe alone, 564 heavy fortifications were to appear, and another 105 between the Vranov Dam and Breclav. The program would cost almost $11 billion.

Fortifications built by 1938. Heavy and light fortifications are marked in red, only light ones are marked in green.

Czechoslovak fortifications were divided into seven main sections:

- northern front between Oder and Elbe;

- northwestern and western fronts with many fortified lines;

- the southern front between the Vltava and the Danube at Bratislava;

- southern front on the border with Hungary;

- northern front on the border with Poland;

- fortification in the Moravian Highlands and east of Moravia.

In the Moravian-Silesian region on the border with Germany, as of 1938, work was 75% completed. The borders with Poland, Hungary and Romania were fortified mainly with light types of bunkers. In 1936–1938, a total of 8,040 objects were built (excluding Slovakia):

- Southwestern sector - 3993 objects;

- Northern Bohemia - 1852 objects;

- South Moravia - 1000 objects;

- North Moravia - 1195 objects.

On the territory of Slovakia, including the Bratislava bridgehead, 11 heavy and 1943 light objects were built. The most powerful fortifications were erected on both sides of the Orlicke Mountains and extended from the outskirts of Náchod to Kraliki.

The fortification line included both medium and light bunkers with lines of obstacles, including anti-tank ones, as well as heavy casemates, like on the Maginot Line in France. In 1938, the construction of fortifications was completed. The Czechs created a more advanced defense system than the Belgians or the French, while refusing to attract foreign construction companies or labor from Germany. The Czechoslovak border fortifications, which stretched almost throughout the country, were called the Benes Line by the Germans.

Main types of structures

Czech long-term fortifications can be divided into three categories:

- Light fortifications. They consist of two types: LO vz.36 (Lehké opevnění vzor) and LO vz.37. These are small reinforced concrete structures with several embrasures for firing. More than 10,000 of these bunkers were built between 1936 and 1938;

- Heavy fortifications. Sometimes they are called blockhouses. These were powerful reinforced concrete structures of IV degree of stability (the thickness of the walls is 3.5 m) - both casemates for infantry and artillery blocks. They could form not only individual protective points, but also a continuous group of blocks;

- Artillery fortresses - “tverzi” (tvrz). These were heavy blockhouses that formed a closed system like a fortress. These included infantry blocks, entry points, mortar blocks and observation towers.

LO vz.37. Šumava mountain range, 1938

The fate of Czech fortifications

On March 15, 1939, Nazi Germany sent troops into the Czech lands and announced the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The army offered no resistance. The Germans had at their disposal not only impressive reserves of weapons, but also many long-term Czech fortifications. After the seizure of the territory of Czechoslovakia, they were inspected by representatives of a specially created committee, which included fortification specialists. The Germans conducted tests on the effects of various types of weapons on these objects. Fire from machine guns and mortars did not cause any harm to them, and artillery shelling for the most part only scattered earthen embankments in front of the objects. Armored bells and domes also survived the tests with honor.

The results surprised German specialists so much that they dismantled most of the domes and installed them on their own fortifications. Particular attention was paid to the Czech 47-mm 4cm Kanón vz.36 cannons, which had good characteristics and a successful design. Most of the guns were removed from the Czech casemates and later, under the name 4.7cm PaK K 36(t), were used on the fortifications of the Atlantic Wall, the Siegfried Line and in the Międziżecki fortified area in Poland.

One of the observation bells

At the end of the war, the fortifications in the Opava-Ostrava region were partially restored and occupied by German divisions during the Moravian-Ostravian offensive operation of the Red Army in March-May 1945. The holes from the domes were temporarily filled with concrete, and instead of the dismantled guns, ordinary machine guns were installed in the casemates. The underground galleries served as shelter for the Germans during artillery shelling.

Disappointing conclusions

The 20th century can well be called the “golden age” of fortification, which developed under the influence of constantly improving weapons and warfare strategies. The construction of huge defensive zones and fortified defenses on the eve of the Second World War became widespread. Perhaps there was no country where fortifications did not appear. The First Czechoslovak Republic was no exception. The Benes line turned out to be very good for its time and, on the whole, was not inferior to the famous Maginot line.

Czech long-term fortifications, the construction of which began in 1933, were not completed by the time the country was captured by German troops. Only some of their sections were completely ready. The long-term fortifications of the First Czechoslovak Republic had not yet been tested in combat when the Czech army abandoned its positions and surrendered to the invaders. And yet the system of Czechoslovak fortifications was quite modern. In combination with favorable natural conditions for organizing defense and with a combat-ready army, they could be very effective and would become an impassable barrier for enemies.

Vladislav Goncharov

/

Belgian Shield: Beginning

History of construction and construction of defensive structures of Fort Eben-Emael

- fortification

- Belgium

Igor Melnikov

/

"Pilsudski Line"

Polish pillboxes near Baranovichi, built in the 30s in case of war with the Soviet Union

- WWII

- fortification

- Belarus

- Poland

Alexey Statsenko

/

Monument to Stalin's fortification

History of bunker No. 401 of the “mine” type in the Kyiv fortified area

- WWII

- fortification

- USSR

The Belgians refuse

A key element of the French plans was the provision that Belgium would certainly become an ally. At first, from its territory they planned to rush across the Rhine - into the fiery heart of Germany, then they planned to defend themselves on its borders. But in 1936 Belgium declared neutrality - and it was a disaster.

King Leopold III of Belgium was a leading proponent of neutrality

Until that moment, the entire defense system was built on the assumption that if it was necessary to repel an enemy offensive through Belgium, then it would have to be done on its territory. No one had any illusions about the Belgians’ ability to defend neutrality - it was clear that if the Germans chose to strike through this country, then, at best, the French would have to act without a preliminary plan. And so it happened.

Attempts were made to cover the Belgian border with newly built fortifications, but a “no money, but you hold on” situation ensued. More precisely, there was money, of course, but it went to aviation and tanks. The fortifications on the Meuse and to the north were quite weak.

Mobilization

But if there were problems with covering Belgium, then the main task - to cover the mobilization and deployment - was not removed. In reality, however, it turned out much simpler than expected - the Germans were engaged in the destruction of Poland until the end of September, they had no time for the French. But later Hitler demanded an offensive in the West, and here the German military machine stalled.

There were no crazy people in the German headquarters eager to storm the Maginot Line.

All planning revolved around the invasion of Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg - so the Line decided to limit the German invasion at the planning stage. In addition, it quickly became clear that the autumn offensive was doubtful due to weather conditions - rumors of excellent European roads in 1939 were greatly exaggerated.

The invasion was postponed many times - until the fateful May 1940.

May 1940

As you know, the central idea of the German invasion plan for France was a strike through the forested Ardennes. This in itself was a big risk. But, let us note once again, the idea of striking through the best road areas of the Franco-German border was not even considered. However, France paid undue attention to this area. It’s amazing that the French kept more troops in well-fortified positions than the Germans, for whom this area was obviously passive.

German advance to the west

Going beyond the Meuse meant going beyond the left flank of the Line's fortifications. Now we know that the Germans were planning a gigantic attack on the English Channel, cutting off the main Anglo-French forces. In May 1940, it seemed that they could strike precisely at the rear of the Maginot Line - fortunately, the operation was on a smaller scale. And these fears were confirmed - the attackers turned south and went to the rear of the fortifications of the small fort of La Ferte.

The French command responded quickly by deploying reserves. The 71st infantry division went to storm the fort. The shelling did not produce any results, but the assault groups managed to approach one of the rising towers and detonate a forty-kilogram explosive charge on it. The tower is jammed. Smaller charges and smoke bombs were used, which were thrown into the gaps formed.

German reconstruction of the capture of the Line fortifications

A fire started, which forced the French to retreat to an underground gallery that connected the two blocks of the fort. The Germans got close to this block and knocked it out of action. The French did not give up, hiding in the galleries. They maintained contact with the command thanks to a telephone line. The command ordered to hold on. But the fires continued, and the sergeant from the fort said that “there is no way to hold out” and he, along with the commander of the fort, “will get out.” However, they were no longer able to do this. The entire garrison - 107 people - died from suffocation.

A little later, the Germans occupied fortifications in the Maubeuge area. They were of the “second stage”, built with significant cost savings and therefore not very powerful. But the main thing is that they were stormed after the German troops managed to reach the rear. Nevertheless, it was there that trends emerged that were later only confirmed during the June battles.

German soldiers near one of the broken fortifications

Both aviation and siege (not to mention field) artillery proved to be ineffective. Another thing is the famous 88-mm anti-aircraft guns. They made it possible to break armored surveillance caps, depriving the French of their vision. They also successfully fired at concrete, although destroying embrasures or breaking through even a relatively thin rear wall required a lot of time and ammunition.

The main thing is that the French could not interfere with anything, because the field troops left the Line, and only garrisons defended it. There was no artillery support, which helped the Germans. After this, assault groups went to storm the heavily damaged fortifications, and if they managed to climb onto the French defensive structures and begin to undermine them with the help of special charges and burn them out with flamethrowers, then the French could only die or surrender.

Device[edit]

Kyiv fortified area, KiUR.

The areas outlined in black and numbered are defense nodes. Defense unit No. 3 close-up. Map legend in footnote[2] A typical “line” consists of separate fortified areas. There may be gaps between areas - but as a rule, these are off-road areas where the enemy will not go in large forces. The fortified area consists of several defense nodes. A defense unit is a group of long-term structures that have a single fire system and operate under a single command. As a rule, a node covers a certain direction (road, defile) and consists of several bunkers connected to each other by communication lines and often by turns (underground passages). Abroad, the defense center was often called a fort in the old way.

Pillbox - long-term firing point

- the main unit of a fortified area. It is a well-protected structure with one or several embrasures. Depending on the time of construction, country and purpose, bunkers could be different - from a small “one-room” bunker for one machine gun to a 3-story “millionaire” with six embrasures.

The firing system of bunkers can be, roughly speaking, of two types: frontal and oblique.

- Frontal - the simplest, when the embrasure faces the enemy. Pros: understandable even to the illiterate, very easy to apply to the terrain, can fire at the area over a long range. Disadvantage: it is also noticeable from afar and is carried out by artillery immediately after opening fire. Typical of the Stalin Line and, to a lesser extent, the Molotov Line.

- Oblique sighting - the notorious casemates of Bourges. The bunker faces the enemy with a blank wall, the firing points are located on the side (and are covered from the front by an additional wall). They shell the area in front of neighboring bunkers - and they, in turn, cover the approaches to ours. Pros: low vulnerability. Cons: difficult to apply to terrain; difficult for infantry commanders to understand. Typical of the Mannerheim Line, widely used in the Leningrad-43 line.

In principle, both options have their own scope, and real fortified areas, as a rule, combined both systems.

- Bunker - wood-earth firing point

. A bunker for the poor, built from matches and acorns by infantry forces. Refers to field fortifications and is built directly during the war, on the wartime line.

Anti-tank ditch

- belonging to many fortified areas. The idea, as always, was good: we make the ditch zigzag. We place anti-tank guns at the breaks to fire longitudinally at the ditch (yes, like in bastions). Even if a tank can, in principle, overcome a ditch, it will be forced to slow down and literally “crawl” over it. Or even wait for the sappers. That's when it will fly on board.

In reality, everything turned out worse. You can't disguise a ditch. Its curves show, with an accuracy of up to a meter, where the flanking guns should be located. After that, finding them and destroying them (at least blinding them) is a simple matter. The walls of the ditch themselves (scarp and counter-scarp) are collapsed by demolition charges, bombs or artillery fire. So, in reality, ditches did more harm than good. The entire position is unmasked. They don't allow a counterattack. And the enemy infantry, having broken through to it, already has some kind of hidden position where it can sit out and continue the attack[3]. And the labor costs are simply wild. So, as we gained experience, we stopped abusing ditches.

Gouges and hedgehogs

- also anti-tank obstacles, but unlike ditches, they are more practical. Cheap. Labor costs for installation are small. They are broken only by a direct hit (that is, one shell per piece, even if you hit, isn’t that a big deal?). They are not completely impassable, but at least they force tanks to crawl rather than fly - and at the same time, unlike a ditch, they do not “tell” which side the guns are on. So they are still used in one form or another.

Wire fences

- obstacles against infantry. Already in the forts of the 19th century, wrought iron gratings were used. They were installed vertically in ditches. The attackers had to climb over them under fire, while these bars did not prevent the defenders from shooting and observing through them. Disadvantages: expensive, difficult to replace if damaged. Therefore, later they borrowed barbed wire from field fortifications. Wire fences began to be placed in ditches on low stakes, covering the entire (or almost the entire) width of the ditch (10..20 m). Other options - high stakes and Bruno spirals - were used less frequently, as they unmasked the position. Subsequently, all available varieties were used in the construction of fortified areas.

Mines

- also an integral part of fortified areas. The first, still imperfect anti-personnel mines were used in the American Civil War (as, by the way, was barbed wire). The second time mines were remembered was during the First World War, where they were used to strengthen an already impenetrable defense. But all this is in a field war. For the fortifiers, the word “mine” still meant an infernal machine, exploded in a tunnel under enemy fortifications. By the way, such things were actually used both at Port Arthur (1904) and in the First World War at the Battle of the Somme (1916).

With the beginning of the construction of long-term fortified areas, mines became an integral part of them. First anti-personnel, then anti-tank. In this case, the purpose of the minefields could be different:

- some were placed on troop routes (roads, clearings) and were covered by fire from bunkers to prevent mine clearance.

- others, on the contrary, were placed on the approaches to bunkers outside their firing sectors in order to prevent the approach of assault groups.

Despite some outcries in favor of banning mines, in reality they are still widely used.

Note

: you must understand that, unlike fortresses, fortified areas were never intended for independent defense: firstly, by definition they had an open rear, and secondly, in addition to the garrisons of bunkers, it was necessary to “infantry fill” the position, otherwise individual bunkers are easily blocked and are destroyed (which often happened).

Breakthrough

In June, the Germans planned a global offensive with a breakthrough of the Line in several places. But here again the concrete spoke its weighty word - the attempts were successful only in the most poorly protected areas. What greatly simplified the task for the Germans was that by this time the field filling (that is, the units that were supposed to sit in the trenches near the pillboxes) had already been withdrawn. Artillery units also left with him, which was especially important.

It would seem that what follows is a matter of technology. Often the fortifications were stormed from the rear, since they could be bypassed by breaking through the Ene River. But in reality, the battles often became extremely stubborn. Moreover, where the French had mutual artillery support for forts, they managed to fight back, despite the tricks of the Germans, including anti-aircraft guns, dive bombers and assault groups. Thus, Fort Schonenburg, despite intensive bombardment by heavy artillery and aircraft, managed to fire 15,802 75-mm shells alone and remained almost unharmed.

Block No. 1 of Schonenburg after the shelling (photo source)

They managed to break through the line along the Rhine, where the fortifications were not so strong. During further battles, the Germans captured several forts, mainly due to attacks from the rear. Moreover, before the truce, only small forts, the so-called petit ouvrage, fell. Large fortresses, grand ouvrage, were never given to the Germans.

The solution was found not at the top, at headquarters, but on the battlefield

To observe the enemies, special armored caps were installed in the Maginot Line structures. Because of their characteristic shape, the French called them “bells” (cloche).

“Bells” were cast from armor steel, with a wall thickness of about 300 mm.

The armor is the envy of any World War II tank.

Some caps were armed with machine guns and were quite capable of clearing an assault group from the “back” of the pillbox.

The turkeys at the top did not give the German infantry effective heavy guns. But the assault units received 88 mm anti-aircraft guns (“aht-comma-aht”, as the Germans called them. - Ed.). They did not formally penetrate 300 mm armor. But the soldiers thought: “What if we shoot many times at one point? The target is stationary, there are shells piled up, the bolt is semi-automatic - you know, throw it...”

The effect was amazing. From a distance of a kilometer, anti-aircraft guns fired shell after shell into the caps - and still broke through the armor. Dot was becoming blind. It was already possible to confidently “poke him in the ear with a ramrod” by the forces of the assault group.

Things went even more vigorously for the German anti-aircraft gunners in the shooting of fortifications on the banks of the Rhine, in the southern sector of the Maginot Line. Using the method “a drop hammers a stone not with force, but with the frequency of its fall”, “aht-comma-aht” they pierced not only armored caps, but also a couple of meters of concrete, leaving only the intricacies of the reinforcement. It is not surprising that the anti-aircraft guns were dragged across the Rhine right behind the infantry: to carry out the next line of concrete boxes.

Brest on the Rhine

However, the matter was decided not by the success or failure of the Line troops, but by the collapse of the defense in the north, which led to the encirclement of a large French group between the Aisne River and the French border. Among them were all the fortifications of the Maginot Line.

After this, disaster became inevitable. However, the fortification troops refused to surrender for a very long time, even after the official conclusion of the truce. The last forts fell only at the beginning of July. At the same time, the commanders had to be persuaded to surrender to the French leadership, which remained loyal to the Vichy regime.

Mannerheim Line or Enckel Line?

The line of defensive structures on the Karelian Isthmus received the name of Mannerheim, the Finnish commander-in-chief, and then the President of Finland, only at the end of 1939, when a group of foreign journalists visited its construction. The journalists returned home and wrote a series of reports about what they saw, in which they mentioned the term that later became official.

Bird's eye view of the Mannerheim Line. Photo source: intpicture.com

In Finland itself, this defense complex was long called the “Enkel Line” in honor of the chief of the General Staff of the young republic, who in the early 20s of the 20th century paid great attention to the construction of defensive structures on the southern borders of his homeland. Construction of the line began in 1920 and was suspended in 1924 when Enckel resigned from his post.

Carl Gustav Mannerheim - commander of the Finnish army. Photo source: kommari.livejournal.com

It resumed only in 1932, when the legendary military leader Carl Gustav Mannerheim, who a year earlier became the head of the State Defense Committee, toured the “Enkel Line” with an inspection and gave the order to complete its construction, strengthen and modernize it.

Italians... as always

A little-known episode of the 1940 campaign is Italy's entry into the war and its attempts to break through the Alpine Line. Despite the overwhelming superiority in forces, the performance of Mussolini's army ended in complete failure. And here the fortifications also showed positive results.

The Italians tried to storm them using armored vehicles, but... they only had wedges.

They immediately lost twelve wedges - they were immediately covered with snow.

The Italians tried to shell the forts, but if the Germans could not achieve success, then the poor descendants of the Romans - even more so. Even armored trains were used, but also without any success.

Howitzers of the Maginot Line

As a result, the Italian infantry managed to reach the structures of one of the grand ouvrage, but they failed to do anything with it. The successes of the Italians throughout the war boiled down to the occupation of the city of Menton. However, the population abandoned this resort town even before the start of the battles.

What is a “Karelian sculptor”?

The Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940 gave the world several new terms. For example, “Molotov cocktail” and “Karelian sculptor”. The last was the Soviet high-power howitzer of B-4 caliber, the shell of which, after hitting pillboxes and bunkers, turned these structures into a shapeless mess of concrete and reinforcement. These bizarrely shaped structures were visible from afar, which is why they received the nickname “Karelian monuments”. The Finns called the B-4 howitzer “Stalin’s sledgehammer.”

The B-4 howitzer is a Karelian sculpture or a Stalinist sledgehammer. Photo source: https://topwar.ru

conclusions

The Maginot Line accomplished almost all of its tasks. It was a really smart decision for the early 30s. The problem turned out to be not in the Line, but in the French army as a whole. Having failed to create modern, properly managed and organized armed forces, France doomed itself, if not to defeat in the war, then to a series of painful failures at the initial stage.

The Maginot Line narrowed the window of opportunity for the Germans, but the French failed to correctly assess the intent of the campaign. Again, the issue is not the Line, but a lack of understanding of the capabilities of the modern army. The soldiers and officers of the forts could only fight bravely and skillfully - which is what they did. But the fate of the entire campaign, alas, was not decided on their front.

Notes[edit]

- During World War II, “lines” were also called lines with conventional field fortifications, even if reinforced with concrete structures. The difference is approximately like between the house of a “new Russian” and a forester’s hut: if the pre-war lines were specially designed to cover sections of the border and included structures on the verge of the country’s solvency (million-dollar pillboxes), then the lines during the war were reinforced with pillboxes whenever possible, most often from prefabricated reinforced concrete, and in those positions that were.

- Black circles with arrows (for example, 416, 417) are pillboxes of frontal oblique fire, each arrow is a sector of fire.

Small black circles with one arrow (420) - small pillboxes

- Square with up and down arrows (410) - caponier

- Triangle inscribed in a circle (407) - artillery observation post

- Small squares with triple arrows (405, 406) are TAUT gun platforms.

- In the battles near Leningrad there were at least two places where the ditch we dug became a strong German position: Nevsky Piglet and the Krasny Bor area.

- For the most part, such blockhouses did not have permanent garrisons; in case of war, they had to be occupied by ordinary infantry.

- Considering the fighting qualities of the Italian army in that war, the honor is still not great. These would have faltered even in the trenches.

- Anti-tank ditches MUST be covered longitudinally by artillery - otherwise they are useless.