Quote from Dragon_North

Read in full In your quotation book or community!

ALL CURVES OF DEATH.

Weapons with a curved blade Among the dead were four warriors whose appearance was not at all similar to orcs. Tall, with large features and slanted eyes. Their swords were wide and straight, while the orcs recognized only crooked scimitars.

J. R. R. Tolkien, “The Two Towers”

It just so happens that authors of works in the fantasy genre consider the choice between curved and straight blades a matter of taste or the so-called “cultural tradition”. A nomad is necessarily armed with a saber, because he is a nomad, this is the custom among them. The samurai wears a katana because only Japanese masters knew the secret of producing such swords... But was it all that simple?

In fact, the choice between curved and straight blades was dictated by practical considerations. The samurai carried a katana, the knight carried a long sword, and the janissary carried a scimitar, because it was precisely such weapons that corresponded to their methods of fighting and the production capabilities of the gunsmiths of that time and a particular country.

| Silk cutting sword |

| Improvements in the quality of steel made it possible to create long and light curved swords. Now they have begun to be of interest to horsemen. |

For the first time, elastic steel - damask steel - was produced by Indian craftsmen back in the 1st millennium BC. e. The technology for producing damask steel was incredibly complex by the standards of the Middle Ages. Pure iron ore and a firebrick furnace were required. At the final stage of smelting, carburization was carried out not with charcoal, but with graphite.

The oven had to cool very slowly—several days. This was the first secret (with very slow cooling, large crystals appeared in iron heated to a plastic state). The second secret was that this process occurs only in unusually pure iron. This required putting graphite (pure carbon) into the furnace instead of coal.

But the result was worth the cost! The damask blade was three times stronger than the welded one, did not break, and could be sharpened to a razor sharpness. A typical “prank” of that time was to drop a silk scarf on the blade of such a sword. The weightless fabric easily fell in two.

However, throughout the Middle Ages, damask steel was produced only in India. It was pointless to “steal” his secret from Indian masters. All the same, graphite was practically not mined outside India.

The first attempts to establish the production of damask steel in Europe were made already in the 18th century. Graphite and refractory bricks were no longer a problem at that time, but sufficiently good ore was discovered only in the Urals. Only in 1830, the Russian metallurgist Anosov, using Tagil magnetite, smelted real damask steel.

Crooked sword

| The Star Wars lightsaber is actually called a saber, although its "blade" is not curved. |

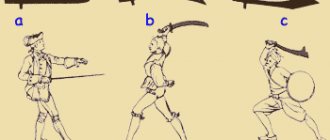

Both curved and straight swords appeared in the Bronze Age. Curve and straight swords differed primarily in balance. The center of gravity of a straight sword was located at the level of the guard or several centimeters higher. The curved sword was balanced approximately in the middle of the blade. Unlike its straightforward brother, it was intended primarily for a slashing blow. The bending of the chopping edge made the blade more durable, and the high location of the center of gravity significantly increased its penetrating power.

On the other hand, the “low” centering made the straight sword a very convenient and “fast” weapon. This opened up ample opportunities for stabbing attacks. As a cutting weapon, a straight sword justified itself only with a weight of 2.5-3.5 kg (and even then only half as well). This forced the warrior to carry an ax in case of meeting with an armored enemy.

Common in the Middle East in the early Middle Ages, a curved sword weighing 1.5 kg and a blade about 50 cm long that flared at the end cut through armor no worse than a twice as heavy European ritterschwert

(long knight's sword). But its “range” was small. And there was no point in making the curved sword long, because with a blade of 100 cm, it would be no different from an axe.

| Short curved swords are the favorite weapons of the “evil” races in fantasy. |

Finally, a curved sword could only have one cutting edge. And this, in the era of weapons production by welding iron and steel, meant half the service life. After all, when struck, the blades quickly became dull and jagged. But the curved sword often had a massive grooved butt. Sometimes several rings were even inserted into the holes on the butt. “It’s more fun when they ring”? No... It was fun when you managed to take the blow of an enemy blade on this corrugation or on the rings themselves. After that, the enemy could only run for a new sword...

| The saber is the perfect weapon of nature. Saber-toothed animals lived approximately 20 million years ago. |

A curved sword had some advantages, while a straight sword had others. But the advantages of straight swords outweighed them for a long time. After all, riders sitting on huge war horses required long blades. During the Crusades, not only European knights, but also most of the Arab cavalry were armed with straight swords.

| Infantry were rarely armed with curved swords. It is inconvenient to chop while standing in formation. The phalangists required piercing swords, which means straight and short - with blades 25-50 cm. The weighty, curved sword of small size was well suited for individual combat on foot. Therefore, it gained recognition, first of all, in medieval Asia among archers and sailors. The Europeans did not neglect such weapons either. So, for example, English archers finished off knights thrown down by wounded horses with falchions - short swords with a widening blade, which differed from their Asian counterparts only in their straight cutting edge. It was more difficult to chop with a falchion, but more convenient to stab. In Rus', such swords were called cleavers. |

Falchions from visual sources

After we have examined the fully or partially preserved artifacts of falchions, it would be correct to begin examining the falchions whose images are in numerous literary and visual sources of the Middle Ages. This point is very relevant, since often, while participating in various events of historical reconstruction, we see blades that claim to be historic thanks only to pictorial sources. What kind of falchions are these?

Secrets of the ancient masters

The main clients of armory workshops in the Middle Ages were horsemen - those who had a horse could afford to buy a sword. And the rider needed a blade that was both long, light and well suited for cutting. After all, an attempt to deliver a piercing blow while moving meant for the horseman, at best, the loss of his weapon. At worst, the gardai broke his wrist.

Before the advent of elastic steel, a straight sword with a “low” balance was the best compromise. But swords made of hard steel were very short-lived and dull. The chopping edge was difficult to sharpen - it crumbled easily.

Only a blade made of an elastic material can be made long, light, strong and sharp, and ancient metallurgists persistently searched for a way to teach steel to spring. But what if it was impossible to melt iron in ancient and medieval furnaces?

A more technologically advanced way of producing elastic steel, which did not require any special ore, graphite, or special furnaces, was found in China in the 2nd century AD.

The iron blank was forged lengthwise, folded in half, then unforged again and folded - this way 30-40 times until there was enough metal. And with each forging there was less and less of it. The hot iron quickly oxidized. The result was a workpiece in which many layers of metal with high and low carbon content alternated. A blade forged in this way could always be recognized by the beautiful wavy pattern that appeared on the blade after polishing.

Using a more advanced technique, a bundle of pre-prepared wire or tape with a certain carbon content was forged. This way, significantly less time and iron was wasted. But even in this case, the weight of the finished product was only 15% of the weight of the workpiece.

| Under the name “woots”, elastic Chinese steel managed to become famous even in Rome. Europeans became acquainted with patterned iron during the Crusades, and began to call it “Damascus steel” or simply “Damascus” - since in the 12-13 centuries the main center of metallurgy in the Middle East was the Syrian city of Damascus. Damascus production technology penetrated into Iran, Syria and Arabia from China in the 6th and 7th centuries. From Iran, Damascus came to Khazaria, and from the 11th century, sabers began to be used in Rus'. The Russians called such steel “red” (beautiful) iron or “damask steel.” Real damask steel was rare even in Asia, and practically never found its way to Rus'. |

| Military turban. |

After the appearance of Damascus blades, blacksmiths began to give way to soft armor. Silk robes have become fashionable in the East. They provided the warrior with excellent protection and, unlike hemp caftans and felt cloaks, did not limit mobility at all.

The Arabs began to wear turbans

- thick strands of coarse nettle fabric. By the 17th century, the turban had turned into a huge hat made of many layers of material, also stuffed with hemp and cotton wool. There was no longer any need to wear an iron helmet underneath. Not only sabers, but also clubs turned out to be powerless against such armor. As sabers spread, chain mail and leather armor were replaced by quilted robes and Streltsy caftans stuffed with hemp and horsehair.

Gunsmiths responded to the advent of soft armor by forging blades with a microsaw

. That is, they began to forge weapons so that the steel fibers were located at an angle to the chopping edge. Then, invisible, but very dangerous, teeth appeared on the blade. There is no point in chopping silk, but nothing prevents it from being cut.

Gross messers and cords

It is impossible not to note the similarities between gross messers and cutlasses/cords used in Eastern Europe: In addition to a similar overall length, namely 1-1.2 meters, all specimens are single-edged with handles for a two-handed grip. The absence of a counterweight on the cords from Bulgaria and the Polish cord allows us to conclude that this feature was characteristic not only of the Gross Messers. On the Bulgarian cords presented below and on 1 Polish cord, in fact, there is no guard, but there is a dowel - a characteristic feature of the Gross Messers. The combination of these parts and the fact of approximately simultaneous production in different parts of Europe speak for themselves.

In general, cords certainly require systematization and their own typology, and we hope that this task will be completed in the near future. What else can be said based on the results... Available information about fakes If you notice inaccuracies in the article or errors, you can contact us at the following addresses: master craftsman Yanbeng master craftsman Varazhbit ZF workshop mail: Yanberg, web mail icq 446713180 icq 469959694

Saber vs sword

| Card “Dancing Scimitar” from the collectible card game “Magic: the Gathering”. |

In the game “Baldur's Gate II”

When visiting the “

Adventurer’s Shop

,” it is impossible not to pay attention to the fact that scimitars are valued in the “

Forgotten Realms

” several times higher than straight swords.

It is also easy to notice that most of the “plus” blades are curved. Take “ Rose Petal

” or “

Dragon Slayer

”.

This is one of the rare elements of historical realism in this game. For the manufacture of long and light curved swords, only elastic steel, which was very rare in the Middle Ages, was suitable. Bulat and damask were very real analogues of fantasy mithril

and

adamantite

. They were priced accordingly.

The ability to reduce the weight of the weapon by three times made shifting the center of gravity to the guard unnecessary. On the contrary, there was every reason to shift the center of gravity to the tip, and bend the blade itself to increase the efficiency of the chopping blow.

A radical improvement in the quality of the material allowed riders to acquire light cutting weapons. the scimitar appeared

- a sword weighing about 1-1.4 kg with a curved blade, expanding towards the tip, 70-90 cm long.

Scimitars were used not only by cavalry, but also by infantry. Back in the early Middle Ages, two-handed scimitars weighing 2.5-3.5 kg and blades 100-120 cm long appeared in China. They were intended, as befits two-handed swords, to fight cavalry. To be more precise - with horses (the Arabs tore off the heads of the horses of the crusaders with such two-handed hands).

In the Middle East, scimitars began to be used in the 6th-7th centuries. But even in the era of the Crusades, such weapons were considered a treasure. Only in the 14th century did scimitars and sabers become the main weapons of Asian cavalry. In the 15th century, swords were replaced by sabers in Rus', although metal for blades was imported to Muscovy along the Volga from Iran.

Almost no Asian weapons reached Western Europe. But already in the 16th century, Europeans began to forge sabers from “English” steel. And in the 17th century, Damascus began to be produced in Europe. Toledo were the first to master the technique of forging blades from a bundle of wire.

.

| European sabers: the blade has a weak or medium bend, the guard is closed. |

| Sabers soon appeared behind the scimitars and gradually replaced them. Improving the skills of blacksmiths made it possible to make the blade narrower and longer. In addition, the expansion was replaced by “elmanya” - a thickening near the tip. Forging a blade with an elmanya was much more difficult than a flat one. But the saber blade, uniform in width, was convenient to put into its sheath. It was indeed difficult to come up with a comfortable sheath for a sword with an expanding blade. Short curved swords of the early Middle Ages were worn without sheaths - simply in the belt, like, for example, axes. It was impossible to tuck a Damascus steel blade into a belt - it would simply cut it. Sometimes scimitars were equipped with their own straps for carrying. More precisely, silk ribbons. One end of the tape was attached to the handle, the second was passed through an eye or ring in the butt. But carrying a sharp sword in this way was not only inconvenient, but also dangerous. The ceremonial American saber is carried on a hook (clung to a ring on the blade) and balanced with a chain. |

| Backpack tool |

| In addition to small combat falchions, heavier swords of this type were occasionally found in medieval Europe, similar to the dwarven “petal” enchanted against undead, mentioned in Perumov’s “Loneliness of the Magician.” Two-handed falchions weighing 5-6 kg were the weapons of executioners. Sometimes, to further shift the center of gravity towards the tip, a lead weight or even a container of mercury was inserted into the butt of such swords! But why does the executioner need such a powerful weapon? Couldn't an ordinary two-handed sword cut a neck on the block? Imagine, I couldn’t! It was considered permissible to cut off the heads of royalty only with a sword and only with one blow. When in the 16th century in England it became necessary to execute Mary Stuart, a specialist and an instrument had to be ordered from abroad. Falchions enjoyed particular success among European sailors of the Renaissance. |

Falchion of Thorpe

The Thorp falchion is a weapon of the late 13th, early 14th centuries, this sword is kept in the museums of Norfolk, England (Norfolk Museums). As E. Oakeshott notes, this blade differs from analogues that were widespread at that time (Cornuese falchion, Hamburg falchion, etc.). The Thorp falchion blade is more like a saber blade. As Oakeshott notes, the genesis of this blade shape is not entirely clear. Before 1290, this blade shape is rarely seen in manuscript illustrations. Perhaps this type of blade was formed under the influence of Eastern European products, since it strongly resembles the Hungarian Charlemagne sword, i.e. a type of blade used since the 9th century. I would like to note some features of the blade: the pommel of this sword is engraved. The falchion blade has two fullers, the first fuller on one side is upper, long along the butt with an end in the form of a tail, on the other - lower, short on the ricasso and also with a tail. Together with the crosshairs of the falchion, the cross-section of the blade is rectangular, sharpening begins after the end of the lower fuller, and sharpening of the blade begins after the end of the upper one. If we consider the internal cross-section of the blade, we get the following: in section C there is a pentagon, the spine is 4.5 mm, in section B there is a pentagon, the spine is 2.5 mm, section A is a hexagon, closer to the tip there is a rhombus. Some characteristics of the sword: weight 904 g, which is significantly less than the weight of the above blades. Blade length 956 mm, blade length 803 mm. Guard length 196 mm. Handle length 100 mm. The special appearance of the Thorp falchion is of particular interest for the reconstruction of such a blade.

Katana

Katana is a very unusual sword. Even much more unusual than is commonly believed. The enumeration of the oddities of the katana can begin with the fact that it is still a sword, although it looks like a saber. The katana has a low center of gravity in common with straight swords. This would seem to indicate the primarily piercing purpose of the weapon.

But why does a piercing sword need a curved blade? It is not comfortable. It is even more inconvenient to stab while holding the sword with two hands, but the handle of the katana is made specifically for two hands. A two-handed grip is required to quickly lift heavy

sword. It in no way contributes to strengthening the blow with a light blade.

The actions of a samurai fighting with a katana are, admittedly, no less strange than the sword itself. The Japanese does not chop or stab, but delivers unusual sliding

blows. He... cuts! This, therefore, is why a second hand is needed. Since the inertia of the weapon is not used (with such weight and the location of the center of gravity of inertia, one can assume that there is no inertia at all), you have to press hard on the handle.

| The completeness and perfection of the shape of a samurai sword is striking. Even the handle (an unprecedented case!) bends back slightly, continuing the line of the blade. |

No bladed weapon inflicted such terrible wounds as cutting weapons. During World War II, Americans warned their soldiers against trying to shield themselves with rifles from the blows of Japanese swords, which easily cut through firearms. But do not forget that it was very difficult to strike with cutting blades. They justified themselves only as armor-piercing weapons, and not against any armor.

But the barrel steel was soft, so the rifle, by and large, is not an indicator of the “steepness” of the katana. Japanese wicker armor, in which plates of hard steel were fastened with silk cords, did not take a katana.

| The katana is not a medieval sword. The katana became what we are used to seeing only in the 17th century. Until the 17th century, samurai were mounted warriors. Accordingly, they needed completely different swords. |

Of course, not only katanas were cutting weapons. In the Middle East in the late Middle Ages, cutting sabers even began to predominate. A classic example is the Caucasian saber, designed for cutting buroks and papakhas.

The checker had a “high” balance, and the blow was delivered sharply, from the body, which, of course, was more convenient for the rider. But then the blade had to be guided

with the same sliding movement as a katana.

This is called “ chopping with a draw

”.

| Checkers: the blade bends weak or medium, there is no guard. |

| War and fashion |

| The shako was sewn from several layers of leather and supplied to the sultan. The Sultan slowed down his saber blade while still “on approach.” |

After the re-equipment of the cavalry with sabers, European protective equipment also became much lighter. The slash can actually only land on the head or shoulders. So the rider’s armor was quickly reduced to a helmet reinforced with a horse’s tail and light shoulder pads made of iron and silk cords - epaulettes. The infantry did not even need epaulettes. Even a dragoon horse had at least 165 cm at the withers - a rider could only hit an infantryman on the head.

In the 17th century, the head, neck and shoulders of the European warrior were protected by a wig. The wig itself, especially if sprinkled with powder, “withstood” the chopping blows of swords. In case of a saber strike, a cocked hat was worn over the wig. A cocked hat with a wig provided better protection than a bronze helmet with a ponytail, but riders for a long time preferred hard helmets. The wig didn't help much when falling off a horse.

In the 18th century, the impractical wig was replaced by a comfortable leather shako helmet with a plume borrowed from Turkish turbans - a tuft of horsehair and wire sticking up. The guards used huge fur hats instead of shakos.

But the most original was the path chosen by the Japanese. Samurai began to wear on their heads something amazingly reminiscent of the legendary shaving basin of Don Quijano (thanks to the “brilliant” translation of Cervantes, better known as Don Quixote).

The Japanese helmet - so flat that Europeans for a long time mistook such helmets for small shields - was worn without a liner. The samurai used his own hair as a “shock-absorbing cap,” weaving it into a tight knot on the top of his head. The helmet, sitting unsteadily on the top of the hair, did not allow itself to be cut. Under the blows he swayed, and even the most “toothed” blade slipped off him.

Cord from the Museum in Warsaw and the Falchion of St. Michael

Analysis of a vast layer of information led us to quite interesting analogies. For example, it was hard not to notice the similarity between the cord exhibited in the museum in Warsaw and the falchion of St. Michael. In view of the fact that the latter has already been described above, we will dwell in more detail on the first: This cord dates back to approximately the second half of the 15th century. It was found near Lake Dabrowno next to Dabrowno Castle (Gilgeburg) in 1898 in Ostróda County. Total length: 78 cm Weight: 0.72 kg Blade length: 64 cm Handle length: 14 cm Of course, this cord could be of either German or Polish origin, but a comparative analysis of gross messers and cords will show how closely weapons weapons developed crafts in Eastern Europe and nearby countries.

Scimitar

| Strongly curved scimitars or sabers had guards of the usual type. |

As mentioned above, Asian gunsmiths knew how to make blades with a microsaw. But for a long time they had to puzzle over how to combine the effectiveness of a cutting blow with the simplicity of a chopping blow.

The result of an intense creative search was the appearance of sabers and scimitars with an unusually strong blade bend. It would seem, why bend the blade at an angle of 40-50 degrees? It will be impossible to stab with such a weapon, and the overall length of the saber will decrease. But the medieval masters knew what they were doing. Ridiculous-looking, highly curved sabers (in Europe they were usually called “ Turkish”

”) turned out to be a terrible weapon.

Such sabers chopped and cut at the same time - the so-called quickdraw

when striking, the blade was struck not by an awkward movement towards oneself, but by a natural downward movement of the hand, using the inertia of the weapon. But it was, indeed, almost impossible to stab with a Turkish saber. Often its edge was not even sharpened.

To give such a sword the ability to thrust, the handle and the tip had to be aligned on the same line, giving the blade a double bend. Khopesh swords also had an S-shape

.

In the Middle Ages, swords with double or even reverse bending were sometimes forged, but only Turkish gunsmiths were able to “bring the idea to mind.” This is how the most powerful bladed weapon appeared - the scimitar

.

| Short scimitars of the Turkish infantry could also act as throwing weapons. |

| Cavalry scimitars: weak reverse bend, no guard. |

| "Ears" of a scimitar. |

In literature, scimitars and sabers are sometimes called scimitars, and sometimes this name is assigned exclusively to Janissary daggers. It is not right. Only a weapon with a small

double bend. The length of the blade could be different. The Janissaries had really short scimitars, but cavalry examples could have blades up to 90 cm long. The weight of the scimitars, regardless of their size, was at least 0.8 kg. With less weight, the weapon became difficult to chop.

The scimitar could be used to stab, chop and cut. Moreover, chopping blows were applied with the upper part of the blade, and cutting blows with the lower part - with the concave part. That is, they cut with a scimitar, like a saber or a katana, so he did not have a guard. But there was a difference. The scimitar did not need to be leaned on with both hands, like a Japanese sword, it did not need to be drawn

like a checker.

It was enough for a foot soldier to sharply pull the scimitar back. The rider had to simply hold him. The rest, as they say, was a matter of technique. The concave blade “bite” into the enemy itself. And to prevent the scimitar from being torn out of the hand, its handle was equipped with ears

that tightly covered the fighter’s hand

from behind

. The heaviest samples had a rest for the second hand under the usual handle.

About the penetrating power of scimitars, it is enough to say that even the 50-centimeter daggers of the Janissaries pierced knightly armor.

| Sword |

| The broadsword, a weapon with a straight blade sharpened on one side, has long been considered in Europe as an alternative to the saber. Most often, the appearance of this weapon dates back to the 16th century, although in fact the broadsword is much older. Straight swords with one-sided sharpening were found in Europe in the 10th-11th centuries; even earlier, the Khazar cavalry was armed with broadswords from Iranian Damascus. Such weapons were known in medieval China, India, and the Middle East. But broadswords received real recognition, even temporary, only in Western Europe. Back in the 18th century, most of the European cavalry were armed with broadswords. Heavy cavalry - cuirassiers - were armed with broadswords in the 19th century. Unlike the saber, the broadsword had a “low” balance, which, along with the straight shape of the blade, made it much more convenient for stabbing. But the broadsword began to cut on par with a saber only if it was 25-30% heavier. Therefore, the weight of European broadswords reached 1.4 kg. European broadsword: straight blade, closed guard. |

Falchions from the Romance of Alexander (ROMAN D'ALEXANDRE) (1338-44)

"The Romance of Alexander" - apparently the first chivalric romance, is considered a medieval adaptation of the groriginal falchion from the Paris Museum. In the images of this novel we can see two-handed and one-and-a-half-handed falchions somewhat similar to the Parisian falchion. In this version (the first type) of the falchion, we see an interesting type of guard; it consists of an arc that protects the hands of both hands, which is not typical for the options discussed above. Various forms of hand protection appear on later forms of falchion crosses. In “The Romance of Alexander” there are falchions similar in appearance in a one-and-a-half-handed version, so in the images knights often hold this weapon with either one hand or two. At the same time, in the images where the falchion is held with one hand, the artist left significant space, which implies the possibility of gripping with the second hand. The geometry of the blade is also of interest; its cutting edge forms a kind of spike, which probably served to pierce armor during a piercing blow. Based on the image, we can come to the conclusion that the part that most closely resembles the butt is the blade. This moment is present in all images, but the lack of archaeological finds of blades with similar geometry casts doubt on the fact of its actual existence... The second type of falchion from “The Romance of Alexander” is a smaller falchion, with a blade very reminiscent of the blade of a Parisian falchion. However, there is a main difference, this is the absence of any guard on the falchion. This falchion has straight shapes and a very elongated tip. Presumably there is a fuller on the falchion, this can be judged by looking at the image. In general, in the process of studying history and in historical reconstruction in particular, the use of pictorial, sculptural and other historical sources has always been generally accepted.

* * *

The merits of the saber are best evidenced by the fact that all other types of melee weapons with a long blade were supplanted by it in fair competition. In the end, the saber managed to defeat even the scimitar.

In the 60s of the 19th century, gunsmiths finally learned how to melt steel. Soon its special variety appeared - “saber”. The new blades, nicknamed “herrings” for their characteristic shade of shine, were not inferior in quality to damask blades - they tore a man apart from shoulder to waist and cut through steel helmets. They could be produced by machine, and therefore were cheaper and more accessible than handmade blades.

For foot soldiers, bladed weapons always had only an auxiliary value. It was impossible to come up with a better weapon for a horseman than a saber. Sabers remained in service with the cavalry as long as the cavalry itself existed.

Falciona from Porte de Hal, Brussels

It will be very interesting to consider a photograph of a falchion from Porte de Hal (Porte de Hal, Brussels) - a falchion of the 14th century, which is extremely rarely mentioned in specialized literature. This blade is indicated in the monograph: European & American Arms by Claude Blair. The falchion is in the Armory of the Duke of Burgundy, Brussels (Museum van het Leger en de Krijgsgeschiedenis” in Brussels). The shape of the falchion blade was actively discussed during a discussion on the Myarmoury.com Discussion Forums. This discussion is connected with the fact that it is assumed that the blade is broken, as stated in the signature under the blade: Falchion of the 14th century (broken) (“14th century falchion (broken)”). Some participants in the discussion suggest that the falchion originally had a shape similar to the Thorp blade. However, another part of the discussion participants disagree with this statement. They think that the falchion blade from Porte de Hal is not broken off and has its original shape. So, during the study of photographs from the monograph European and American Weapons by Claude Blair, a crack was discovered on the blade itself; perhaps this circumstance was indicated in the signature under the blade in museums. It was not possible to determine exactly whether the falchion blade was broken; the museum workers did not answer the question of the Myarmoury.com Discussion Forums participants. Also, we can note the dating of Claude Blair, which is more accurate: 1300. As we can see, the blade has a simple square blade shape, which, judging by the image, has a fuller located from the guard to the “tip” of the blade. The blade is also equipped with a guard and pommel typical of that time.

Literature and sources used:

1. Oakeshott, Ewart: The Archeology of Weapons 2. Oakeshott, Ewart: The Sword in the Age of Chivalry, Boydell & Brewer, Woodbridge 3. Klenner Alexander. Article: “Falchion. Cutting and piercing weapons” (Alexander Klenner’s “Hieb & Stichwaffen: Das Falchion”) 4. Hellquist Bjorn. Conyers-falchionen, Den sista av sitt slag? 5. Encyclopedie Illustree Les Armes Blanches de Jan Sach. 6. Jan Peterson. De Norske Vikingesverd 7. Kirpichnikov A.N. Old Russian weapons. Swords and sabers of the 9th – 13th centuries 8. Y. Bokhan. “Zbroya Velikaga of the Principality of Lithuania 1385-1576” 9. Y. Bokhan in his article “Structure of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania troops in the second half of the XIV-XV centuries.. 10. W. Boeheim. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Das Waffenwesen in seiner historischen Entwicklung vom Beginn des Mittelalters bis zum Ende des 18 Jahrhunders 11. Claude Blair. European & American Arms by Claude Blair 12. SC Cockerell. Maciejowski Bible. Pictures from the Maciejowski Bible, Phaidon Press Ltd – London 13. Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1588, edited by Shamyakin I.P. 14. Site materials: myArmoury.com 15. Site materials: Sword Forum International 16. Site materials: Also City 17. Forum materials: “Tradition” 18. Forum materials: FREHA Authors of the article: master craftsman Yanbeng +375 29 687 99 64 Velcom +375 25 987 74 58 Life master craftsman Varazhbit +375 29 575 75 58 MTC ZF workshop mail: Janberg, webmail icq 446713180 icq 469959694

Disadvantages of falchions

However, the weight of the falchion could also be its disadvantage. Historians believe that attacking with heavy weapons involves wider and sweeping movements that leave warriors open to attack by the enemy. This may not be so critical in a one-on-one duel, but it is very unfavorable on the battlefield, so the falchion was only an auxiliary weapon for the knights. Another disadvantage is its length. Most falchions are short swords, which imply close combat. Soldiers had to get their opponents within close range before striking, and thereby exposed themselves to danger.

News aggregator 24SMI

Types of falchions

If you look at how this weapon is classified, you can see that there are only two types:

Classic falchion. This weapon is most often found in historical engravings of the time. Most likely, this is what most medieval mercenaries were armed with. This falchion is straight with an unsharpened blade spine. It is believed that this weapon is a direct descendant of the scramasax, but the combat knife of the ancient Germans had a blade that was at least twice as thick; A curved falchion that resembled Arab swords. This weapon had the first half of the blade partially sharpened on the other side of the blade. This weapon gained popularity only in the 15th and 16th centuries.