Russian edged award weapons

Russia was the first in world practice to create a system of awarding edged weapons, and it is unique in its own way. In tsarist times, award weapons occupied a special, honorable, exclusive place.

Such an award could only be received by an officer who participated in hostilities and showed personal courage. But historically it turned out that the first awards with edged weapons, or awards, as they were called in Russia in the 17th-20th centuries, took place sporadically and were, so to speak, amorphous in nature. However, there could not be clear regulation, since, say, at the beginning of the 17th century there was no regular army.

Among the first awarded were princes, governors, stolniks, hetmans, that is, those people who were able to expel foreign invaders, such as Prince Skopin-Shuisky, who liberated Moscow from the Poles in 1610, or Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, who gathered and armed the militia, and dozens of other people who participated in various wars of the 17th century.

This tradition of rewarding “irregular” soldiers was undoubtedly archaic and sometimes even had nothing to do with the conduct of hostilities. Proof of this is the awards given to the Cossacks who annually visited the capital on rather prosaic matters, such as receiving allowances from the treasury, various types of equipment, ammunition, etc. At the same time, the original system was absolutely democratic, since among those awarded were not only atamans, military foremen, esauls, centurions, but also ordinary Cossacks. The same can be said about the awards given to the elite of other faiths in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Bashkiria, who diligently served the queen or king. It is appropriate to note here that the words “pay”, “salary”, “reward”, “reward”, “reward”, “reward” have the same semantic meaning and imply a reward for a particular act for the benefit of the state, marked by the supreme authority in the person of monarch.

The complained system for the Cossacks, which developed during the reign of Anna Ioannovna, lasted almost a century, until the end of the reign of Emperor Alexander I. The latest blades with solemn, and sometimes naive and lengthy inscriptions, made using the technique of gold or brass carving on steel or damask steel with dates from 1801, 1821, 1822, 1823, preserved in the Hermitage, some museums of the Central Asian CIS countries and private collections. I am not aware of any later awards of this type, although the term “grant” itself appears in award documents up to 1917.

Award sabers for the Cossacks of the 18th and early 19th centuries are a unique phenomenon. From the point of view of weapons art, they amaze with their individuality, precise targeting, personalization and many other differences. Specific people were awarded for courage and fortitude shown in enemy (Tatar and Turkish) captivity, for the invaluable and necessary work of an interpreter (translator), simply for “services in Moscow”, “for many faithful services”, “for his considerable time and honorable service" (read - length of service), "for... brave actions against the enemy" and so on.

The Don Cossacks had the largest number of granted sabers. In museums and private collections there are separate award blades for other Cossack troops - Grebensky (later Terek), Ural, Zaporozhye.

This type of awards (commissioned Cossack sabers) has not been thoroughly studied or described. This is a separate topic that requires much scientific research. We can only say with a certain degree of confidence that not a single Cossack army was spared awards. Information about such award blades is periodically received from Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, Poland, Canada, Great Britain and other countries. Proof of the existence of material monuments is the prize saber of the Kuban Cossack army, made in honor of the 200th anniversary of the KKV in 1893 using traditional techniques of the 18th century.

What was an award edged weapon before the inscription “For bravery” appeared on it (on its various elements). Let’s immediately make a reservation that we will be talking about the awards of the highest military ranks and the military elite of the Russian regular army, created by Peter the Great, about the 18th century, in which Russia won brilliant victories in the North, West and South. The military feats of those military leaders who proved themselves in battles on water and on land were also assessed according to victories.

Oddly enough, the initiator of the system of awarding luxurious gold weapons decorated with diamonds was personally the modest Peter I. He himself did not have such weapons, but it is quite obvious that, while in European countries, he saw something similar at other courts. It is possible that A.D. Menshikov, who did not suffer from modesty, suggested to him the idea of special awards. But the reason for such an award was the defeat of the Swedish squadron (a very worthy and famous opponent of Peter I) at the island of Grengam on June 27, 1720. General M.M. Golitsyn, commander of the Russian fleet, “was sent a gold sword richly decorated with diamonds as a sign of his military work.” This is undoubtedly a military award. After an almost 20-year break (sources have not yet been found), other awards followed based on the results of military campaigns, and since the 40s of the 18th century, dozens of military generals of the Russian army and navy were awarded gold swords and daggers. Among them are P.S. Saltykov, E. Laudon, A. V. Buturlin, de Brillie, V. Lopukhin, M.N. Volkonsky and many others. On a special occasion - for the defeat of the main detachments of the rebel Pugachev - Lieutenant Colonel I. I. Mikhelson was awarded gold and a sword with diamonds.

Under Catherine II, the wording “For brave labors” and “For brave enterprises” first appeared in award documents for the year 177±. But no inscriptions have yet been made on weapons in diamonds. The cost of award swords at that time was astronomical - from 5,000 to 15,000 rubles in gold. The award sword of the undisputed brave Potemkin-Tavrichesky was valued at 21,000 rubles.

Only a few swords of this kind have survived. All of them were already considered unique works of Russian jewelry art. Judging by the copies that have come down to us and their images in the portraits of the recipients, there were no two identical swords. We can say with complete confidence that most of the blades of award swords are trophy ones, that is, of European origin (Swedish, German, rarely English).

Award weapons with diamonds differed significantly from the examples of average combat officer swords. But there is no information about award gold broadswords, sabers and checkers in the period from 1720 to 1788.

Gold weapons decorated with diamonds continued to be awarded to those who distinguished themselves in military work throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Decorations in the form of laurel leaves or twigs began to appear on award weapons. Since 1913, the St. George weapon, for example, was necessarily decorated with laurel decoration.

Until 1844, gold weapons with or without diamonds could be similar to the authorized ones only in their general features. This concerned mainly the hilts of swords and sabers. Blades, as already noted, could be quite arbitrary and very often of foreign origin. Since 1849, award weapons had to fully comply with the highest approved combat standards. Gold weapons of old and non-statutory designs were allowed to be worn, but only outside formation.

In 1854, Emperor Nicholas I ordered the price of gold award weapons to be reduced somewhat. From this year, the standard of gold for its production was lowered from 72 to 56. Some researchers believe that all gold award weapons were issued from the Emperor's Cabinet, but this was not entirely true. There is reliable information that the awardees were given certain amounts of money to make gold weapons (including diamonds), and the awardee himself ordered them from gunsmiths. Considering that most of the officers were not rich, they, at best, slightly updated an ordinary combat sword or saber, engraved inscriptions on the hilt, and re-gilded it, although it remained brass. In fact, diamonds most often turned out to be rock crystal or rhinestones.

To reward generals who achieved the most significant victories, special types of weapons were developed. In some cases, the emperor personally made amendments to the sketches, as a rule, reduced the cost of weapons, and ordered the number, size and even colors of precious stones that adorned the golden weapons. In accordance with the highest decree, when transferring a recipient from one type of military service to another and, naturally, changing standard edged weapons, the inscriptions were repeated, which is why the same inscription can be found on a saber and on an epee, on a broadsword, a saber and a dagger.

Since 1859, all officers awarded golden weapons were equal to the Knights of St. George. In this regard, on golden weapons it was now necessary to wear a lanyard not on a silver galloon ribbon, as before, but on a St. George ribbon, black and orange. Generals wore weapons decorated with diamonds or stones that replaced them, without a lanyard, since its very appearance spoke of the special status of the award.

Speaking about the granted weapons of the 18th - early 19th centuries, it should be noted that the inscriptions on Cossack and heterodox sabers directly indicated the surname, first name, rank of the recipient, for which he was awarded and, first of all, which monarch granted him. All the inscriptions began like this: “We, by the grace of God, are the Empress (Emperor) of Great White Rus', etc., etc.”

Since the 20s of the 19th century, not only the exact dates of victorious or especially bloody battles, but also the names of units and the names of officers who ordered weapons to their commanders or colleagues began to appear on the blades of combat weapons. Award blades with such characteristic inscriptions indicate a high degree of respect and admiration from colleagues or loved ones.

In one of the private collections there is an award blade for the Russian-Japanese War, on which a woman’s name is carved in calligraphic letters. This most likely indicates that the blade could have been made for the recipient by order of his beloved woman.

As already noted, golden weapons were issued until the complete unification of the statuses of golden and St. George weapons, that is, until 1913. The last time golden weapons were awarded was for the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, which was generally lost by Russia. For various reasons, golden weapons for this campaign were issued with a delay of five or more years, however, the delays were even longer.

According to well-known sources, golden weapons with and without diamonds (until the moment when the recipients were equated with the Knights of St. George) were issued more than 5,800 times. The number of blades in use should be significantly greater for the following reasons:

a) a mandatory duplicate weapon without decorations with diamonds, diamonds, emeralds - for everyday wear in the service;

b) repeating the attributes of an award weapon on a newly adopted model;

c) the existence of two types of weapons in the branches of the military: a saber-dagger - in the navy, a broadsword-saber - in the Guards heavy cavalry, a saber-saber - in the light Guards cavalry;

d) gift options for award weapons (from colleagues and relatives). If this is a fact, then the number of reward items should be almost twice the number of awards. First of all, this concerns award weapons with precious stones, but, as we know, not only;

e) cases of repeated awards are also known.

Based on the iconography and examples of award weapons with the inscription “For Bravery” that have survived to this day, we can say with confidence that on Cossack weapons of the 18th - early 19th centuries it could have been on the blade, scabbard, crossguard of the saber, on the back or side of the handle. The inscription on the blade was made using the technique of notching on steel on the front, that is, the right leg of the blade. An example is a saber blade dated 1786, from the collection of the Ministry of Foreign Culture.

The inscriptions on the scabbard and side cheeks were also located on the front side of the saber, depending on the way it was worn. And this method, in turn, depended on the location of the belt rings of the scabbard. According to the fashion of the time and, of course, according to the habit of the owner, sabers were attached to the sword belt with the blade up or the blade down. That is why the front could be either the right or left side of the blade. This is clearly visible in the ceremonial portraits of the collection of the Novocherkassk Museum of the History of the Don Cossacks. The inscription on the crosspiece was dictated by the same circumstance and was subsequently made on both sides of the crosspiece of sabers and the heads of checkers (with the exception of Caucasian ones).

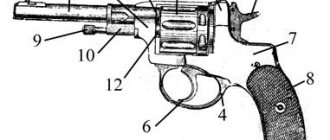

On Cossack checkers of the Don type, which were normally worn with the blade up, inscriptions were made on both sides of the head using a chisel, and the quality of the inscription depended only on the skill of the engraver. In any case, these were variations of soft, rounded calligraphy (Fig. 1). Traces of gilding in the inscriptions are not always found, since upon receipt of the badge of the Order of St. Anna or St. George, many ordered an inscription on their favorite and proven weapon and cared little about the shine of gilding and the novelty of the weapon.

Officer's checkers of the Caucasian and Asian designs, mounted in silver and even gold, are distinguished by great variety, but what they have in common is only one inscription “For bravery” on the front of the head of the handle. There are both calligraphic inscriptions and almost printed rectangular fonts (ill. 2, 3).

In early and more expensive types of weapons, the ornament itself had specially engraved places and designated places for one or another sign. Some recipients placed the inscription “in the old-fashioned way” on the front of the handle. Most often, checkers are found with a silver ribbon soldered or riveted onto the ornament with the inscription “For bravery” and the sign of the order placed in the center of the head. The inscriptions are stamped and engraved, with and without niello. Again, on early objects the letters may be applied (1831).

On the award sabers and checkers of officers of Georgian origin, there are inscriptions in two languages (Russian and Georgian) on both sides of the saber cross and the head of the checker handles.

The general name of the granted weapon for the Cossacks of the 18th century is saber. But during the reign of Catherine II, patent sabers with typical “headed” handles, without protective saber crosses, also appeared.

From the point of view of the typology or classification of award weapons for the Cossacks of the 17th - early 19th centuries, sabers are in first place in terms of the number of surviving monuments of material culture. There are three main types of sabers: Persian, Turkish and Polish. The main differences can be seen in the handles. The materials for their manufacture and decoration were: wood (poplar, boxwood), horn, jade, steel, silver, brass, leather. The finishing is also varied - steel cut in gold, silver, copper. Engraving, blackening, gilding, applied monograms and floral ornaments, casting and embossing - in a word, all known metal processing technologies.

The same can be said about blades. They are mostly of eastern origin. From simple wedge-shaped to complex monocotyledons, dicotyledons, polycotyledons with elman. On many blades there are Persian, Turkish and Crimean marks, sometimes figured cartouches using the gold carving technique with suras from the Koran. Lots of damask steel blades.

As a sign of respect for national traditions, the “complaint” inscriptions on some blades are duplicated in Arabic (for Muslims). There are inscriptions in Georgian.

Since the end of the 18th century, a laconic inscription “For bravery” appeared on award weapons, which was placed both on the hilts and on the blades.

Based on the documents of the Chapter of Orders, back on May 20, 1797, it was the highest approved that the order’s sword (weapon) when changing the class of the order remains with the recipient. This meant that the person awarded the 3rd degree of the Order of St. Anna, after receiving higher awards of the 2nd or 1st degree, continued to simultaneously carry weapons with the badge of the lower, 3rd degree. Award weapons, however, like other highest awards, were returned to the Chapter of Orders. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the Order of St. Anna received 4 degrees, retaining edged weapons for the lowest 4th degree.

Although the inscription “For bravery” on the “Anninsky” weapon was officially enshrined in the order’s charter in 1829, this act was a formality. The inscription has existed since Catherine’s times and was placed on all types of officer bladed weapons received for military operations (ill. 4-6).

In 1845, for non-Christians awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 4th degree, according to the highest decree, instead of a cross a black enamel eagle was placed, but, as before, under the imperial crown crowned with a cross.

In 1859, in connection with changes to the “Regulations on Service Awards,” it was noted that class ranks who were under enemy fire, but did not participate in hostilities, could be awarded the Order of St. Anna of the 4th degree, but without writing the inscription “For bravery” on the bladed weapon. At the same time, an order lanyard was also required. The weapon itself was an approved combat weapon, assigned to one or another branch of the military. There are minor differences in the finish and size of the hilts, which are explained by the fact that there were many private workshops and stores of officer items, factory manufacturers, weapons arsenal workshops and large regimental workshops. In addition, officers could order weapons for themselves and their colleagues while on vacation abroad ( in Germany, Spain, Austria-Hungary and other countries). The inscriptions “For Bravery” were engraved in Russia. There are cases from the First World War when, having received an order to award the Order of St. Anna of the 4th degree, officers, for lack of good engravers, ordered watchmakers to make an inscription on their personal weapons.

Until 1914, a huge number of officer blades, amounting to thousands of pounds, were imported into Russia through various channels (ill. 7-17). Approximately 60% of blades for officer weapons were produced in Russia (ill. 18-23). The Warsaw, Kiev, Moscow, St. Petersburg arsenals remounted thousands of captured blades, placing Russian hilts on them. V.A. Durov writes in his book that bronze elements of weapons - hilts and instruments - were not always covered with gold. This is not true. There is not a single object in museums and private collections that does not have traces of primary gilding. This applies to combat standard weapons. The officers' Cossack sabers of the Caucasian and Asian samples had silver and steel devices with silver or gold cutouts - the kind that the owner ordered.

One cannot help but mention the insignia of the Order of St. Anna, for edged weapons. According to available sources, the first signs were tombak, but they are not in collections. The first known signs from the early 19th century are in several collections. They are made of thin sheet gold of high standard, the thickness of the plate is 1 mm, the diameter of the outer circle is 16 mm, the height of the circle together with the crown is 21 mm. The sign is made by hand using engraving technique. Two identical signs are known in Moscow: the first is in the State Historical Museum, the second is in a private collection. Both signs are attached to the flints of cavalry sabers of the early 19th century using two thin claws and soldering with tin (ill. 4).

When the Patriotic War of 1812 began, the Chapter of Orders sent tombak badges to the troops. We know for sure that these signs without swords began to arrive in 1813. Gold insignia is found on infantry half sabers of the 1826 model, on cuirassier broadswords of the 1826 model, and on Caucasian sabers. On Caucasian and Asian checkers there are very often signs made in silver (Fig. 2, 3).

Dimensions and weight of St. signs Anna was not regulated, so they could and were different in different periods. The color of the enamel varied from carrot to dark cherry (ill. 24, 25, 26). Among the signs from the reign of Nicholas II there are four types: cast, enamel, solid cast together with the head or fastening nut of checkers of the 1881 and 1909 model without enamel, stamped, covered with enamel on two legs and engraved by hand, covered with enamel and even permanent paint. Since many fakes have appeared, the authenticity of the sign can be determined by an honest, experienced collector or museum expert.

The insignia of the Order of St. Anne had to be attached in places approved by orders. True, in addition to the “ordered” places, the “cranberry”, as the sign was called in the troops, was attached to the handles of dragoon checkers of the 1881, 1909 model (ill. 27), on the front (ill. 28) and end parts of the head of dragoon checkers (ill. 29 ), on the lower frame of the handle, on the mouth of the scabbard and even on the steel scabbard of light cavalry sabers of the 1827-1913 model (ill. 30), on the cups and nuts of official swords (ill. 31, 32), on individual shields - after being awarded gold or St. George's weapon (ill. 33).

According to various estimates, the signs of St. Anna of the 3rd, and then the 4th degree for weapons during the period of their existence, more than 13 thousand people were awarded.

Since the complete merger of the gold and St. George weapons, which began to be called “St. George”, that is, since 1913, and in fact since 1914, the tradition of decorating general hilts with diamonds has continued. The 1913 statute officially established the rules for the manufacture of St. George's weapons and base metal with its obligatory gilding, but in the note it allowed the manufacture of the hilt and the device from gold at the expense of the recipient himself. For all types of weapons, it became mandatory to decorate the device with a laurel ornament. As in ancient times, the ornament was not clearly regulated, so laurel leaves and twigs, especially on devices, could differ, depending on the place where the weapon was made. Various private ornaments were created at their own discretion and were done using different techniques - from casting and stamping to individual chasing and engraving. As a rule, the main material was brass, but red copper with subsequent gilding is also found. In official orders they wrote: the hilt and scabbard are made of copper (ill. 34).

The insignia of the Order of St. George was also made from different metals, depending on the type and size of the bladed weapon. The smallest dagger cross has a distance between the ends of the beams of only 9 mm. (ill. 35), for tombak with enamel - the average size is about 16 mm. On one of the daggers the size of the cross without enamel is 19.5 mm (ill. 36). The average size of crosses for checkers is approximately 21 mm (Fig. 37). On one of the Caucasian checkers, a silver cross with enamel, measuring 25.5 mm (ill. 38), is attached mainly to 2-4 legs.

The St. George's weapon is, first of all, a reward for the First World War, in which officers of the Russian army showed truly massive heroism. In just over three years, more than 5,700 people were awarded the St. George weapon, more than were awarded golden weapons in the entire 19th century. This type of award is quite fully represented in museums and private collections. In recent years, it’s rarely come across.

Today's Russian collectors have many questions regarding this type of collecting. For example, is it possible, or, more precisely, is it allowed in our country to collect edged weapons, including premium weapons? Does the government encourage such private collecting?

Judging by the fact that from Vladivostok to Belgorod or Kaliningrad there are many private collections of edged weapons of varying quality and quantity, it is possible. But, according to current legislation, any movement, purchase, sale and even restoration of it is a criminal offense. Without eliminating this contradiction, there can be no normal civilized gathering. Individual blades, and sometimes entire collections, are periodically confiscated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and are not always returned to their rightful owners, even after a year.

In addition, today you can easily buy a fake. Over the past 10 years, I have repeatedly come across crude or, on the contrary, too elegant fakes, fancy and very professionally made. Attention should be paid to the fit and marking of hilt elements, carvings, fastening of signs on weapons, inscriptions, stamps, etc. You should not buy or exchange a collectible without consulting museum experts and experienced collectors. And one more thing: trust any restoration of your collectible edged weapons only to trusted specialists, and not to random acquaintances.

Valery SABLIN

Photo by Igor NARIZHNY.

Magazine "Antiques, art and collectibles", No. 15 (March 2004), p. 62

Dagger

The dagger has been known since ancient times. There was no tradition of owning these weapons in the Russian Imperial Army. With the exception of the troops who fought in the Caucasus. There, daggers of various lengths and shapes became widespread, some reaching 80 centimeters in length and allowing for not only piercing, but also chopping blows.

Thus, Lermontov’s detachment, which terrified the highlanders, practically did not use firearms, relying on a dagger and saber in close combat. In the 19th century, daggers were ordered from Germany, and then their mass production was established in Zlatoust.

A special type of dagger was the bebut - a weapon with a short curved blade that made it possible to deliver piercing, cutting and slashing blows in close combat. Bebut in 1908 was adopted by the lower ranks of machine gun teams, then by a significant part of the artillery, as well as by mounted infantry scouts. During the First World War, when in 1915 the sides switched to positional warfare, the bebut also found itself in the arsenal of assault groups for operations in trenches and trenches.

Sword

In Russia, the sword has been known since the 17th century. During the period of Peter the Great's reforms, this weapon, along with the broadsword and saber, was in service with both infantry and cavalry. The art of wielding a sword required considerable experience, and in the first cavalry battles, Russian dragoons were initially defeated by the Swedish cavalry, which overthrew the enemy without firing a single shot.

Therefore, it was not uncommon in the Russian camp for Russian dragoons to force Swedish prisoners into battle with blunt weapons, learning difficult fencing techniques. And by the time of the battles of Lesnaya and Poltava, Russian dragoons, using a combination of firearms and swords, had already defeated the Swedes more than once in cavalry battles. However, the sword is gradually being replaced in heavy cavalry regiments by the broadsword, and among the hussars and lancers by the saber.

In fact, the sword becomes the personal weapon of officers. The fighting qualities and importance of the sword, both in Russia and in Europe, are gradually falling - from a fairly long weapon that allowed piercing and chopping blows, the sword turns into an attribute of military and civilian ranks. Although in fairness, we note that assessing the effectiveness of any bladed weapon in infantry against an enemy operating in columns mainly with long guns with a bayonet is also problematic

Pike

The pike originally appeared in Russia in the 17th century, in the infantry among the “new order” regiments. As in any other army, the task of the pikemen was to provide cover for riflemen and artillery. At the beginning of the 18th century, the pike almost disappeared from European weaponry with the rapid adoption of the bayonet with a bow. Subsequently, the pike was used by Russian Cossack units in wars with the European enemy, when, when attacking in close formation, it was possible to overturn the enemy’s cavalry formation.

Initially, pikes were used by almost the entire Russian regular cavalry, but very quickly they remained in service only with the lancers. In the hussar regiments, pikes were left only at the first ranks. Thus, in the cavalry battle of Libertkwolkwitz in 1813 (prelude to the “Battle of the Nations” near Leipzig), Seslavin’s hussars, using pikes, overturned the formation of French dragoons.

But in the fight against Asian opponents and in the Caucasus, where the battle often broke up into a number of separate and even individual battles, the pike did not justify itself and often its use ended in very sad consequences for the Russian cavalrymen. The pike continued to be in service with the Red Army until 1935, although at the parade on November 7, 1941 in Moscow, the pike can also be seen among the Soviet cavalry as a ceremonial weapon.

Sword

The broadsword has been known in Russia since the 16th century. This is a weapon with a long straight (or slightly curved) blade. As a mass-produced weapon, the broadsword became widespread in Russia under Peter I, during the creation of dragoon regiments in the first quarter of the 18th century. These weapons were produced not only in Russia, but also imported from abroad, mainly from Germany.

In the army of the Russian Empire of the 19th century, broadswords were in service with heavy cavalry - dragoon and cuirassier regiments, as well as for a short time in horse artillery and mounted rangers. The opinion that the cuirassiers, these “knights of the 19th century,” had very heavy broadswords is not entirely accurate. The Russian broadsword of the 19th century, as a rule, was even lighter than a cavalry saber. As a ceremonial weapon, it was reintroduced at the beginning of the 20th century among cavalry guards, although the combat value, like most edged weapons, is steadily falling, turning the broadsword into more of a ceremonial weapon.

Saadak

| Saadak. Moscow. Armouries. 1673 Master Prokofy Andreev. Materials: leather, silver, fabric, wood. Sewing: gilding, niello, carving. Beam length 72 cm; quiver length 41.5 cm Made of leather and decorated with embroidery with silver and gold threads. The design of the saadak is extremely interesting, giving it special historical value. In the center, in the figured stamp, there is an image of a panorama of the Kremlin at the end of the 17th century, which was revealed to the viewer from Red Square: the Kremlin wall is surrounded by a deep ditch, through which bridges are thrown to the towers. Saadak is one of the few surviving monuments whose design depicts territorial emblems of the late 17th century. The central composition of the beam is surrounded by round stamps depicting the Novgorod, Kazan, Siberian, Pskov, Tver, Perm, Moscow, and on the quiver - also the Ryazan and Smolensk emblems, which later formed the basis for the city and regional coats of arms of these lands. Saadak belonged to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. | |

| Bow and arrows. 17th century Leather, wood (from the collection of the State Armory Chamber). | Saadak . Moscow. Armouries. 1667 Masters: Prokofy Andreev and Ostafiy. Materials: leather, silver, fabric, wood. Sewing: gilding, niello, carving. The length of the bow is 75 cm, the length of the quiver is 44 cm. Bow and arrows from the 19th century. Figures of griffins, pegasi, firebirds and other fantastic creatures are embroidered on green leather. |

| Takhtuy – a cover for the bow and quiver. Belonged to Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich, second. half 17th century. Case for the bow – 80 cm, case for the quiver – 60 cm. Italian silk, gold threads. | From the “Great Outfit” of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich: bow and quiver for arrows. The items were made in the workshops of the Moscow Kremlin in 1627-1628 by a group of Russian and foreign gold and diamond craftsmen under the supervision of the okolnichy V. I. Streshnev and clerk E. Telepnev // Russian enamels of the 11-19 centuries from the collections of the State Museums of the Moscow Kremlin, State Historical Museum, State Hermitage. - M., 1974. |