Man in his development was constantly guided by expediency and extreme necessity. This is clearly visible when you look at the tools of human labor, weapons and technical inventions. First hunting, then war - these two factors have always been the engine of progress, pushing humanity to new ingenious inventions. At first, primitive axes and spears were used for hunting. The weapons of primitive tribes were similar. After a certain period of time, it was the turn of the wheel and bow and arrows. Humanity quickly realized the advantage of new inventions, trying to use them in the military sphere.

The first firearms

Weapons have always been at the forefront of human thought. Often becoming not only a means of obtaining food, but also an instrument of violence. Some types and types of military equipment were used to arm soldiers; other hunting equipment and devices were used for domestic use, in particular for hunting. Only the advent of gunpowder dotted all the i's, pushing smooth-bore weapons to first place. Gunpowder not only revolutionized the idea of the possible strength and power of weapons, but also allowed man to once and for all secure the right of the strongest on the planet. Having received such a powerful tool as the unsightly-looking powder into its hands, humanity did not fail to take advantage of its colossal power.

Never before have people had anything like this at their disposal. Reliable and proven in battles and hunting, the bow, catapults and ballistae could only at first successfully compete with firearms. However, technological progress did not stand still. As time passed, new means of production appeared, thanks to which firearms acquired their true power and might.

Specifications

But so far the weapon has not undergone major changes. And such conservatism in military craft did its job: the guns adopted in different countries were quite similar in technical characteristics, size, weight, caliber. As the weapons industry developed, all states sought to unify their weapons, adopting a single model for use. It turned out so-so, and several different muskets could be in service at the same time.

The same gun models have been used for decades. The British fired from the Brown Bess in both the Seven Years and the Napoleonic Wars, and the Prussian Potsdam Musket of 1723 was used even at Waterloo.

Soldiers of the 34th, 35th and 36th Regiments of Foot with Brown Bess rifles, 1755

The caliber of the guns ranged from 19 to 15 mm. Moreover, gradually both the musket and the bullet became lighter, and the caliber decreased.

During the revolution, the French went so far as to reduce the diameter of ammunition to 15.5 mm. The reason is simple - due to the collapse of production during the revolutionary years, gun barrels became of less quality, and a tightly fitting bullet could cause a rupture. And the soldiers began to be trained much worse. They could no longer maintain the accepted rate of fire, spending too much time loading.

So the “invincible” French infantry spent all of the Napoleonic wars with bullets dangling in the musket barrel, which did not have the best effect on accuracy.

The British and Prussians, who were proud of their guns, did not value the work of French gunsmiths at all.

The weight of the products was usually in the range of 4.6-4.7 kg - which is noticeably heavier than modern infantry small arms, but not too different from the rifles of the late 19th century, with which European armies fought back in World War II.

Smoothbore weapons at the dawn of their appearance

The first practical experiments with gunpowder conducted in China showed the enormous power of the new substance. Unsightly at first glance under normal conditions, the powder, when exposed to a spark, flame or high temperature, released a large amount of combustion products, which, when used correctly, performed enormous useful work. This unique property was first used by the peoples of the East, where fireworks were created, and the first primitive missiles were used in combat. Subsequently, military technology developed rapidly, resulting in the appearance of firearms. In the 14th century, almost all leading European armies and the troops of the eastern rulers began to receive the first samples of firearms.

Antique trunk

At first timidly, then more and more rapidly, a new type of weapon is gaining its position, becoming the main type of weapon in the ground armies and navy. The first samples had the simplest design. The basis of any firearm was a metal barrel. Initially, it was assembled from plates tightened with steel rings. Subsequently, the barrel began to resemble a metal pipe with one seam. Naturally, when blacksmithing and the steel industry were still in their infancy, the quality of barrel manufacturing left much to be desired. The first examples of firearms, including small arms and artillery, were smooth-bore.

Over time, the shape of the weapon's stock underwent changes, the trigger mechanism was modernized, and the quality of the barrels was improved, but the basic concept remained unchanged for a long time. Over the next six centuries, smoothbore weapons did not change fundamentally, remaining the main type of weapon for the army. Armies are equipped with arquebuses and arquebuses, muskets and guns. Times change, and so do the sizes of small arms. The advent of pistols brought changes to civilian life. Smoothbore rifles and pistols are becoming a mandatory attribute of a wealthy person. Hunting techniques with a bow and crossbow are becoming history.

In private, smoothbore hunting weapons are becoming a favorite tool of professional and amateur hunters.

Classic

The main reason for the growing popularity of this type of weapon was its simple design, high lethality and the ability to hit a target at considerable distances. Even with the advent of rifled weapons, hunting barrels did not lose their position. The hunting rifle is becoming a cult weapon that has become firmly established in human everyday life.

Accuracy and distance of shots

If you take an 18th-century musket, set it at an angle of 45 degrees and fire, the maximum flight distance of the bullet will be only a thousand meters. Of course, no one shot in such an exotic way, and therefore the maximum firing distance with the gun in a horizontal position did not exceed 250 meters. Moreover, even this very small distance was considered not very effective. It was recommended to start firing from 200 meters, and the best results were achieved when shooting almost closely - 100 meters or less.

But that's something else. Cavalrymen armed with pistols were instructed to fire a volley at point-blank range, because already at a distance of twenty steps it was extremely difficult to hit the enemy with a smoothbore pistol. Especially on horseback.

Replicas of English flintlock pistols of the 18th century

On the same topic

What types of bayonets are there: from a club to an opener

Shooting at a great distance only wasted ammunition and was therefore suppressed in every possible way by the commanders. Moreover, the enemy, distinguished by good training and stamina, could, without firing shots, get close, fire a powerful volley with the entire line of infantry and “hit with bayonets.”

This tactic brought many victories to both the revolutionary French army and Suvorov’s Russian regiments.

But even at close range the accuracy was poor. On average, the deviation of a bullet from the firing line was more than half a meter, so that only massive fire from tightly lined battle formations could be used to defeat the enemy.

Rate of fire

Loading an 18th-century musket took place in 12 steps. All of them clearly regulated the actions of the soldier - from preparing the gun to firing to pressing the trigger.

Loading a musket in 12 steps

The recruits memorized the techniques to the point of automaticity in order to ensure the maximum rate of fire in battle. It was the rate of fire of the infantry that was the key means of victory.

On the same topic

Rehearsed War: What is Linear Tactics?

At short combat distances, the side that could provide the greatest mass of lead flying at the enemy most often became the winner.

Therefore, the soldiers of the Prussian king Frederick the Great, whose army consisted of rabble collected by recruiters throughout Europe, relied not on stamina, but on training and speed of fire. And most of the time it worked great.

In 1783, the Prussian Lieutenant General Count of Anhalt proudly wrote that during exercises his infantrymen fired seven shots per minute and managed to reload their guns six times. The Prussian Regulations of 1779 required all infantry commanders to achieve a rate of four rounds per minute. This result was achieved only with ideally structured daily training and required large expenditures on gunpowder and bullets. Therefore, most European armies considered achieving a rate of two or three rounds per minute to be quite sufficient for victory.

Prussian infantry covers the retreat of their troops in the Battle of Kolinsky, 1757

It was with this frequency that Russian and French troops of the Napoleonic Wars era fired. But as soon as poorly trained recruits arrived in the regiments during large campaigns, the rate of fire dropped sharply.

Weapon care

On the same topic

Black powder, why are you freaking out...

Despite the simplicity of the design, the guns required constant maintenance. This was due to the use of smoky “black” powder, which quickly contaminated the barrel with soot and unburnt particles. It was believed that after firing no more than 60-65 shots, it was necessary to stop firing and thoroughly rinse the barrel. To do this, it was necessary to disassemble the weapon - that is, during the battle such an operation was completely impossible.

So during most battles of the “lace wars” era, the soldier had time to fire very few shots.

Exactly 60 rounds of ammunition lay in the cartridge bag of a Russian infantryman in 1812. It was believed that such a reserve was quite enough for the most fierce battle. A little? But the course of the battle in those days consisted of a long wait, sometimes under enemy artillery fire, a slow approach to the enemy in a formation step, and then an exchange of shots, after which the weaker side retreated.

On the same topic

Weapons high-tech of the 18th century

By the way, the diversity of weapons did not interfere with the war at all, because bullets at that time were either made by regimental craftsmen, or even cast by the soldiers themselves. The infantryman himself had to ensure that he had something to shoot with.

Even faster than the barrel, combustion products clogged the seed hole, through which the flame from the flintlock flange ignited the gunpowder in the barrel. Its cleaning was much simpler and could be carried out directly in battle using a special long and durable needle. Such a needle was worn on a chain attached either to the belt of a cartridge bag or to a button of a uniform.

Despite their care, flintlock muskets were characterized by frequent misfires. One in six shots was considered an acceptable result. And every second shot could have gone wrong for a careless soldier.

In damp weather, gunpowder lost its flammable properties, and the number of misfires increased. Well, fighting in the rain was considered almost impossible.

A very important part of the weapon was a small flint, the impact of which caused sparks that ignited the gunpowder. It was enough for 50 shots, after which it was necessary to loosen the screw and install a new one. The soldier always carried a supply of flints with him.

Firearms in the Russian army from XIV to the Mosin rifle

Infantry fusee of 1715 Since 1731, all fusees, with the exception of those intended for garrison infantry, began to be made not with iron, but with a copper device, although the iron device made the fusee cheaper by a ruble. They accepted this increase in price because copper did not rust and frequent replacement of parts was not required.

Speaking about weapons production in Russia, we can safely call the 18th century the beginning of the unification of weapons models.

In the 18th century, the following can actually be distinguished:

For the infantry - soldier's fusee, soldier's guards, rangers', officers' and fittings.

For cavalry - dragoon fusée, dragoon guards, smoothbore carbine, rifle carbine and pistol.

Hand mortars and blunderbusses stood somewhat apart.

Fuzee, fitting and gun of the army of Peter I (first quarter of the 18th century)

It is necessary to note the fact that non-standard weapons appeared in the 18th century. It owes its appearance to an unusual coincidence of circumstances.

When Peter I was visiting Prussia, he received a rather original gift from King Frederick William II. These were amber wall panels that were made for one of the rooms of the Potsdam Palace under construction.

Difficulties encountered during the production of this masterpiece prevented its completion. And then Frederick, known for his stinginess, gave Peter I the already unnecessary amber panels. This is how the famous Amber Room ended up in Russia.

Flintlock carbine. Master Bereshnya, 1660-1670

In gratitude for this gift, Peter sent 55 Russian soldiers of enormous stature to Prussia, knowing that only giants were recruited into the Potsdam Guard. Naturally, the soldiers were uniformed and armed here in Russia.

Documents have been preserved that in 1716, 36 fuzes “for giants” were ordered at the Tula Arms Factory according to the Berlin model for Prussian grenadiers. Probably, it was these guns that served as the prototype for the fuses that were later armed with the Russian guards.

Jaeger rifles were lighter and somewhat shorter than ordinary soldiers' rifles: this was due to the specifics of combat. The first huntsman teams were created in 1765. The task of the rangers - light riflemen - was to fire at the officers and non-commissioned officers of the attacking enemy.

Flintlock percussion guns. Made in Russia, 1780s.

It must be said that the huntsmen were selected to be nimble, energetic soldiers with a height of no more than 167 cm. Therefore, if the grenadiers had guns 155-160 cm long, then for the huntsmen the fuses should have been no longer than 115-130 cm. The fittings had rather short barrels with rifling .

We find the first mention of the manufacture of fittings at the Tula Arms Factory in documents from 1715, but very few of them were made then. The fittings entered service with the Jaeger units, and only for the first rank. In 1786, a battalion of rangers (907 people) relied on 66 rifles.

The reason was probably not only that rifles were more difficult and longer to load than smoothbore guns, but also that they were more expensive. If a fusée with a copper device cost 3 rubles 50 kopecks, then a fitting in 1782 cost 5 rubles 23 kopecks.

Officer's rifles were distinguished by a wide variety of decor and materials used. The richness of the gun's decoration depended on the wealth of the officer who ordered it.

Since 1704, it has been known that dragoons had their own fusees, although there are no scrupulous descriptions of them during this period. A decree of 1715 specified the caliber for lower rank guns: 0.78 inches.

According to documents from 1718, it takes 20 pounds of iron to make the barrel of an infantry fusee, and 18.5 pounds of iron for a dragoon fusee (Russian pound is about 410 g). Naturally, the cavalryman was entitled to a lightweight model.

In the regular cavalry, pistols were immediately introduced as an integral part of the rider's weapons. The same decree of 1715 sums up the many years of combat use of pistols and defines a model that lasted 20 years without the slightest change. Total length - 53.5 cm, barrel length 35.7 cm, caliber 17.3 mm, weight 1.3 - 1.5 kg.

In 1735, the gun device was slightly modified, but other parts of the guns remained constant until the end of the 18th century.

It is interesting that during this period carbines were put into service, with 27,600 smooth-bore carbines required, and 5,520 rifled carbines.

Each gun was supplied with 100 rounds of ammunition: 20 with a soldier in his cartridge bag, 30 in regimental boxes, 25 in an army convoy and another 25 in army warehouses. The main state suppliers were the Tula, Olonets and Sestroretsk arms factories.

The beginning of the 19th century was characterized by constant military operations, which required enormous costs, and therefore government subsidies for factories, including weapons factories, were reduced. As a result, the service life of the weapon increased. During this period, the official service life of a gun was 40 years.

After the War of 1812, domestic factories spent a very long time repairing and remaking trophies, which made the weapons of the Russian army even more diverse. At this time, more than twenty-five calibers were in use, and only in 1821 it was forbidden to remake and repair old guns in factories.

The beginning of the 19th century was the heyday of flintlocks.

The infantry rifle of the 1808 model had a caliber of 17.7 cm, a barrel length of 115 cm, a total length with a bayonet of 185-190 cm, a weight without a bayonet of 4.8 kg, a powder charge weight of 8.5 g, a bullet weight of 27.7 g, initial bullet speed 460-520 m/sec. This gun served as a model for many flintlock-percussion, muzzle-loading guns.

Experiments on creating capsule systems have been conducted since the end of the 18th century. Explosive compounds were invented in France. The chief royal physician, Boyen, discovered mercury fulminate in 1774 and studied its properties. In 1778, the famous experimental chemist K.-L. Berthollet discovered the very composition that we now call Berthollet salt. But the French did not use their discovery for military purposes; the British did. And in 1807-1825, the first experimental capsule guns appeared in Europe.

The structure of a capsule lock: a) locking bar, b) fire tube, c) firing pin, d) trigger, e) trigger, f) safety.

In 1825, Emperor Nicholas I ascended the Russian throne. Almost immediately he took up issues related to the rearmament of the army.

Under Nikolai Pavlovich, new modifications of guns began to appear one after another. A simple listing of the years when weapons were modernized - 1826, 1828, 1839, 1844, 1845, 1852, 1854 - speaks volumes about how much attention the emperor paid to this issue.

In 1831, an agreement was even concluded with England for the supply of one hundred thousand guns for the Russian army.

Confidence in the integrity of British manufacturers was immediately shaken. Out of 85 thousand, only 8682 guns turned out to be suitable without modifications. As for the remaining 76,318 units, they were distributed as follows: 23,416 guns, which after minor modifications can be considered suitable; 32,975 guns requiring major modifications; 6153 - subject to factory testing; 5196 - doubtful; 7768 - unusable, with cracks and, finally, 810 - completely unusable. In addition, almost all guns were of different lengths.

After this unsuccessful experience with foreign supplies, Russia set a course for the development of domestic weapons production.

In 1844, there was an order to convert all flintlock-percussion guns to percussion guns according to the French model.

Then the production of flintlock-percussion guns at the factories ceases, and the production of capsule guns of the following seven types begins: infantry gun (1845), Cossack gun (1846), dragoon gun (1847), soldier's pistol (1848), carbine (1849), fitting ( 1849) and an officer's pistol (1849). It was characteristic of the reign of Nicholas I that new models entered the troops immediately upon their approval.

Samples of rifles of the Russian army of the mid-19th century.

Approved by the Technical Committee in 1852, the new model of the gun was not approved by the emperor, because its weight exceeded the previous one by 29 spools, that is, by 123.5 g, and only after the weight was reduced was approval taken place.

In 1855, new Neusler cylinder-hemispheric bullets were introduced to the 1852 model gun, thanks to which the firing range of smoothbore guns almost doubled.

The history of the appearance of these bullets is quite interesting.

During one of the raids, the defenders of Sevastopol found a pack of cartridges with bullets of a special device from a captured Frenchman. The prisoner explained that these are secret bullets for smoothbore rifles that fly 400 meters or more.

The cartridges were sent to St. Petersburg, where they were examined by the Technical Committee.

Neusler bullets for a 19th century infantry rifle

On February 18, 1855, Emperor Nicholas I died. New bullets were approved already under Emperor Alexander II by order of March 18.

The 1852 model was the last smoothbore gun. Within two years, a sample of a “conversion” gun with rifling in the barrel was accepted.

The middle of the 19th century is characterized by the emergence of conveyors, which made it possible to produce cartridges of a single type in quantities sufficient for the needs of the army.

The possibility of mass production of cartridges gave impetus to the development of breech-loading shotguns.

Millions of muzzle-loading percussion rifles lay in warehouses in European countries. Competitions were announced for the best conversion of old muzzle-loading guns to a new breech-loading system.

Russia did not remain aloof from this movement. The members of the Technical Committee were the brightest minds in Russia of their time, and their outlook and knowledge of the general situation gave them the opportunity to correctly identify a model that not only could be used by the troops, but also that our industry could master. Thus, the system of Captain-Lieutenant Baranov, which Tsarevich Alexander Nikolaevich really liked, was decided to be produced at the Izhevsk Arms Plant.

They armed the sailors with the Baranov rifle. The plant received an order for the production of 10,000 units, but when almost all the guns had already been manufactured, the Technical Committee discovered that the system of the Czech gunsmiths Crick was much cheaper to remake and easier to operate. Arms factories began to produce conversion systems for the Krik, while they decided to send the Baranovsky guns to the navy.

The technical committee explained its decision quite aphoristically: “A soldier without a gun is not a soldier, and a sailor without a gun is a sailor.”

The systems of Thierry-Albini, Snyders, Green, Belyamin and many others were also considered. Basically, they belonged to the so-called snuff bottles (the breech cover of the barrel was tilted to the side or up) and were more or less similar to each other. The trigger with the striker was pulled back, and after inserting the cartridge and closing the lid, the trigger was pressed.

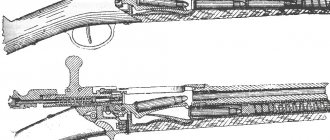

Conversion shotguns with snuff breech. Schematic illustration.

In the mid-1860s - early 1870s, specialists from both countries, independently of each other, made an important discovery.

In 1866, in France, Chassepot invented the sliding bolt. And in Russia at the same time, two captains - Gorlov and Gunius, while undergoing training in the United States, remade the rifle of the American Colonel Berdan almost beyond recognition. The American snuff-box system was replaced by a bolt-action mechanism.

Wintoaka Berdan No. 2 (“Russian rifle”) Throughout the world, this system was called the Russian rifle, and in Russia, it was called the Berdan rifle No. 2. In the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878, our army was armed with rifles of the Crick system, and the regiments The Guards Corps received the new Berdan No. 2 system.

The Turkish cavalry had American Winchester repeating rifles, the so-called civilian weapons, which had very low lethal force.

Winchester rifles

At first, the Russian soldiers were stunned by the barrage of bullets, because the rate of fire of Winchester rifles was unheard of at that time, but they soon realized that these bullets could only cause a temporary painful shock, but not kill. And the Russian infantrymen responded to the shower of enemy bullets with calm, aimed fire, as if at a shooting range.

At the end of the 19th century, there was an intensive development of repeating rifles. In 1883, the master of the officer rifle school, Kvashnevsky, proposed a four-line rifle with an eight-round under-barrel magazine.

The technical committee decided that under-barrel magazines were unacceptable for military-style rifles.

The rifle of Guards Captain S.I. aroused general interest. Mosin, which he presented to the commission each time in new modifications.

Three-line rifle of the Mosin system of the 1891 model Mosin won the competition with L. Nagan, and in 1891 his model of the three-line rifle was adopted for service, which served in the army for more than fifty years.

catalogCatalog of edged weaponsBayonets, knives, daggers (photo, technical characteristics)

permitsRegistration of weapons (obtaining permits)

saleHow to sell your weapon

storageWho and how often can check the storage conditions of weapons

morePurchase of cartridges, gunpowder, bullets, etc.

licensesPurchase of edged weapons

© 2022 GunsLaw

Map Mail: [email protected] About the project

Licenses:

Rifled Smoothbore Self-defense Cold Collecting

Permissions:

Receipt Renewal Re-registration For dagger

Additionally:

Inheritance Med. inquiries Buying cartridges Catalog of bladed weapons

The British don't clean their guns with bricks.

The atmosphere of splendor that reigned on the battlefields of the 18th century demanded that the weapons be thoroughly cleaned, the metal parts gleaming in the sun, and the leather belts given a fresh coat of white paint.

I immediately remember N. Leskov’s story “Lefty”. “The British don’t clean their guns with bricks,” the Russian gunsmith told the emperor about how future opponents of the Russians in the Crimean War take care of their muskets. But in fact, Lefty’s words relate to the later era of the proliferation of rifled weapons, which really were not worth cleaning with sand or brick chips.

Throughout the 18th century, this is how smoothbore muskets were cleaned by the British, Russians, and French. Durable gun steel hardly suffered from coarse abrasive, and if over the years the barrel turned out to be “bored” and slightly increased its caliber, it’s okay. There was no need to conduct aimed fire anyway.

Although 18th-century firearms are often treated with disdain in 19th- and 20th-century works, the muskets of the armies of Rumyantsev, Frederick the Great, or Moritz of Saxony were effective weapons. They fully coped with the tasks that the commanders set for them. Although the inventors of the Age of Gallant anticipated almost all engineering solutions adopted already in the 19th century, producing complex weapons was too expensive. The resulting effect did not cover the costs. The weapons revolution occurred only when the possibilities of the industrial era made available what had previously been considered the pinnacle of weaponry.

British experience

Perhaps, the British were most interested in the idea of accurate shooting at the enemy.

In 1756, the 62nd Royal American Rifle Regiment was created in the colonies, which was planned to be used against the French who threatened British possessions in the New World. Typically, most of the rank and file of the new unit were Germans, who at that time were considered natural shooters.

Already in the Napoleonic era, in 1803, the 95th Infantry Regiment appeared. The same one in which the famous Lieutenant Sharp served from the novels by Bernard Cornwell and the series with Sean Bean.

In an effort to create an ideal military unit, the British command even took unprecedented liberties - corporal punishment was practically not used in rifle units.

This was in those days when an army without flogging was considered not a regular army, but a gang of robbers and murderers.

Conservative Britons were no strangers to interest in technological innovations. During the American Revolutionary War, British Army Major Patrick Fergusson formed and armed an entire detachment with special breech-loading rifles. Fergusson's shooters demonstrated excellent results, firing up to four to five shots per minute. For rifled weapons this is an excellent indicator. However, the new model guns turned out to be phenomenally expensive and required regular and most thorough cleaning. At the same time, they very often broke down, requiring repairs from the best gunsmiths, which is why they became just an experiment and were soon forgotten.

British marksman with a Fergusson rifle