The invention of gunpowder is, without a doubt, the most important milestone in the history of military affairs. Modern historians cannot say for sure who invented it and when. There is a theory about the cunning Chinese, as well as a version about the German monk Schwartz, but it is likely that the circumstances of the appearance of this substance are forever lost to us in the dark depths of centuries. But something else is well known: how and in what way gunpowder came to be used.

First there were guns, large and very large. They were mainly used to destroy enemy fortifications and cities. However, progress did not stand still. The development of technology allowed the Europeans to quickly create a light portable firearm that could be controlled by one fighter - the arquebus.

It is believed that this happened around the beginning of the 15th century. Already at the beginning of the next century, the arquebus turned into a fairly advanced hand-held firearm, which European armies began to use en masse. Moreover, the arquebus of that time had almost all the elements that can be seen in modern small arms: a long barrel, a wooden stock, a butt, a trigger mechanism and a matchlock that initiates the shot. The arquebus can confidently be called the great-great-grandmother of all modern rifles, machine guns and carbines.

The massive use of handguns has radically changed the tactics of warfare. The growing firepower of the infantry put an end to the centuries-long dominance of heavy cavalry on the battlefield. Arquebuses—and later muskets—became effective against the French men-at-arms and Swiss pikemen who dominated the European battlefield in the early 16th century.

However, the emergence of relatively light firearms had more important consequences. It turned out that heavy metal armor was not able to protect its owner from a bullet, so from a necessary element of protective equipment it turned into a heavy and expensive burden, which was quickly abandoned. This, in turn, led to a revolution in bladed weapons; the heavy long swords of the Middle Ages were replaced by the sword.

By the middle of the 16th century, “fire combat” units appeared in every European army. In Russia, the arquebus was called a “pishchal”. In the 16th century, the first domestic units armed with firearms appeared. These were archers.

The appearance of the arquebus

Firearms appeared in Europe around the beginning of the 14th century. At first these were massive cannons that were used in the siege of enemy fortresses. They shot cannonballs or metal arrows. The exact date of the first artillery shot on the European continent is still a matter of dispute among historians. In the illustrated manuscript De Officiis Regum, according to which the young English king Edward III studied, you can find a fairly accurate description and illustration of the cannon. This source dates back to 1326.

The first guns were large, simple and primitive. They were loaded from the muzzle, had extremely low accuracy and rate of fire, and often exploded when fired. Despite this, attempts to make firearms mobile and suitable for hand-held use were made almost immediately after the use of gunpowder began.

The first type of mobile firearms can be called the so-called hand cannons. Two examples of such bombards have survived in Italy; they are considered the oldest in Europe. Both cannons are cast in bronze, one of them bears the date 1322. There is also a large amount of written evidence of the use of “portable bombards” in various military conflicts of the 14th century.

Hand cannons were small guns that were mounted on a wooden handle or stock, loaded from the muzzle, and fired bullets or small cannonballs. Numerous images of these weapons have been preserved. Some hand cannons were mounted on long shafts, the rear end of which was stuck into the ground, and the front end was supported by hands or a bipod. Such tools were also called “hand culverins.”

Over time, they became a very important factor on the battlefield. You can read about their use in sources describing the events of the Hundred Years War or the Hussite Wars.

The most important period in the development of firearms was the 14th century. This century saw major changes related to its appearance and design. Firstly, the improvement of gunpowder production technology and its formulation has made it possible to significantly reduce the weight and dimensions of small arms. Secondly, its shape began to change. The rear wooden part began to expand, and they began to use it to more securely fix the weapon during a shot. This is how the butt appeared. Later it received the usual curved shape, which also made it possible to reduce the recoil of the weapon.

And thirdly, the shot initiation system has changed. For hand cannons, the ignition hole was located at the top of the barrel. Gradually it moved to its right side, where a so-called shelf appeared - a platform on which refueling gunpowder was poured. Gunpowder was initially ignited using a hot rod, wire or coal. It is clear that this method was poorly suited for field conditions. It was much more convenient to ignite using a smoldering wick. A cord or piece of cloth soaked in saltpeter burned evenly and slowly. However, direct application of the wick to the fuse was dangerous for the soldier, as a result of which the wick lock was invented.

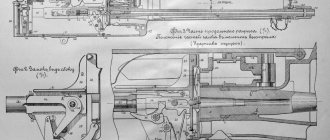

The matchlock consisted of a special clamp for the wick (“dog”, “snake”), which was attached to a metal strip rotating around an axis. The lock was located on the right side of the weapon, next to the shelf and the ignition hole. By pulling the lower edge of the strip, it was possible to lower the lit fuse onto the shelf with refueling gunpowder and initiate a shot. Later, the matchlock developed into a rather complex mechanism associated with the trigger guard, equipped with several springs. To protect it from external influences, they began to place it inside a wooden butt.

At the beginning of the 15th century, two new types of handguns appeared on European battlefields: the gakovnitsa and the arquebus. Structurally, they were similar to each other, but their sizes and functions were quite different. The effectiveness of the first harks and arquebuses was low. Contemporaries often noted that firearms of this period terrified the enemy more with their roar and flames than inflicting real damage on them.

The name “hakovnitsa” comes from the characteristic hook that was located under the barrel of the weapon. With its help, it rested against a fortress wall or other object to reduce recoil. It is believed that tacks appeared in Germany at the beginning of the 15th century. The German name for this weapon is hakenbucdse, which translates as “gun with a hook.” Hakovniks are sometimes divided into two types: heavy ones, intended for stationary use, and light ones, which could be operated by one person. The first type was usually used in the defense of fortresses. Although, it should be noted that such a division is somewhat arbitrary. Shot guns came to Russia from Poland and Lithuania; they were called “zatinnaya pishchal”, that is, a gun designed for shooting from behind a fortress palisade (tyna).

The light hook had a length of about one meter, a caliber of 30-40 mm and a ignition hole on the side. Initially, the shot was initiated using a red-hot rod or wick, which was brought to the ignition hole. Later, hooks with a wick lock appeared. They were much more convenient.

Historians believe that the first arquebuses appeared around the first half of the 15th century; the oldest images of these weapons date back to this period. A distinctive feature of the arquebus was the presence of a trigger, which activated the matchlock. The caliber of this weapon was smaller than that of the tacks. The weight of the arquebus was approximately 3-4 kg, and the caliber was 15-20 mm. It should be noted that there is noticeable confusion on this issue. It is clear that the first arquebuses were not much different from light harks, although the latter were still more “serf” weapons. In some medieval drawings, the term archibuso generally refers to artillery pieces. Arquebuses were also called crossbows of a special design that fired lead bullets rather than bolts. It is likely that we will never know where and when the arquebus was invented. Several nations lay claim to this honor.

It is believed that arquebuses were first used en masse by the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus (this is the mid-15th century); in his mercenary army, every fourth infantryman was armed in this way. There is also evidence that light guns were used during the Burgundian Wars.

However, the truly triumphant procession of the arquebus began already in the 16th century. By this time they had turned into quite complex and sophisticated weapons. Arquebuses performed well in the battle of Ravenna, during the siege of Prato (1512). During the Battle of Pavia, 3 thousand Spanish arquebusiers managed to defeat 8 thousand French horsemen, clearly demonstrating that the era of chivalry had come to an end. After this, not a single major battle in Europe was complete without the use of firearms.

In the first quarter of the 16th century, another type of small arms appeared on the scene - the musket. The origin of the name of this weapon is very vague. There are several hypotheses on this matter. According to one of them, musket is a derivative of the word moschetto, the name of a young sparrowhawk. The Italians believe that this "musket" comes from the name of its inventor - Moschetta from Feltro. In general, a musket (compared to an arquebus) is a heavier small arms, of a larger caliber, with significant penetrating power. The musket can be called a super-heavy arquebus. When shooting from it, some kind of support was usually used: a fork bipod or a reed.

It was possible to increase the effectiveness of arquebuses and muskets with extremely low shooting accuracy by increasing the total number of barrels and organizing massive salvo fire. European arquebusiers and musketeers often used a tactic called caracol. Its essence was that when built in three lines, only the first row of shooters fired, and their comrades standing behind loaded weapons and handed them over. Using such a simple technique, it was possible to conduct almost continuous fire.

The arquebus was used until the end of the 16th century; later wheel locks began to be installed on it; arquebuses with rifled barrels are known. However, by the beginning of the 17th century, arquebuses were almost universally replaced by muskets. After a few decades, the musket became much lighter, so the need for a bipod was no longer necessary.

Mechanism

The arquebus was of a larger caliber than its predecessors. Until the mid-16th century they were dismissed by the matchlock mechanism, after which newer wheellock mechanisms were used instead. The flared muzzle of some examples made it easier to load the weapon. The name 'hook gun' is often stated to be based on the bent shape of the butt of the arquebus. It might also be that some original arquebuses had a metal hook near the muzzle, which may have been used for mounting against a hard object to absorb recoil. Since all arquebuses were handmade by various gunsmiths, there is no typical example.

The neater mechanism of the early arquebus most often resembled that of a crossbow: a gently curved lever pointing backward and parallel to the stock (see illustration of a Spanish arquebus-wielding warrior below). Squeezing the lever against the stock lowered the dry, which was in turn connected to the base of the snake, which held the match. Viper then brought the match into the flash pan to ignite the ignition, firing the weapon. By the later 16th century, gunsmiths in most countries began to introduce the short, neater perpendicular stock that is familiar to modern marksmen. However, most French matchlock arquebuses retained the crossbow style trigger during the 17th century.

File:Arquebus mp3h3700.jpg|Installing the weapon on its support attaches

File:Arquebus mp3h3720.jpg|Aiming, pass the trigger

File:Arquebus mp3h3722.jpg|The lock lights the fuse

File:Arquebus mp3h3723.jpg|The main fuel is lit, and a lot of smoke follows

Characteristics of arquebuses and muskets

The average arquebus of the first half of the 16th century weighed no more than 4 kg and had a caliber of 6 lines (15 mm). She used half ounce bullets, which is about 15 grams. A musket of the same period could reach a weight of 5.5 kg and have a caliber of 7–8.5 lines, and sometimes 9 lines, which is 17.8–21.6 mm or 22.9 mm. The musket ball weighed two ounces or about 60 grams. It is easy to see that the difference between a musket and an arquebus is quite significant.

Back in the 70s, experiments were carried out regarding the tactical and technical characteristics of the arquebus and musket. A heavy lead bullet weighing 58 grams accelerated to a speed of 330 m/s, although modern gunpowder (14 grams) was used for this. In the 16th century, the weight of gunpowder was usually equal to the weight of the bullet itself.

The 16th century musket was a deadly effective weapon. It penetrated armor at a distance of 100 meters, and hit an unprotected target - a person or horse - at a distance of half a kilometer. It was the musket that “signed” the final verdict on heavy plate armor; the arquebus was not powerful enough for this.

True, the sighting range of the musket (as well as the arquebus) left much to be desired. Usually it did not exceed 50 meters. It should also be noted that the rate of fire of the musket was lower than that of the arquebus due to the greater mass of the weapon.

In the 16th century the first pistols appeared.

Efficiency

As a low-velocity firearm, the arquebus was used against enemies who were often partially or fully protected by sheet steel armor. Plate armor, worn on the torso, was standard in European combat from about 1400 until the mid-17th century. Good plate suits would usually stop an arquebus ball at great distance. It was common practice to "test" (test) armor by firing a pistol or arquebus while wearing a new breastplate

A small dent would be surrounded by an engraving to draw attention to it. However, at close range it was possible to penetrate even heavy cavalry armor, largely dependent on the power of the arquebus and the quality of the armor

This led to changes in the use of armor, such as three-quarter plate, and finally the retirement of plate armor from most types of infantry.

The development of volley fire - by the Dutch in Europe, and the Chinese and Portuguese in Asia - has made the arquebus a practical advantage for modern militaries. Volley fire allowed armies to turn their regular formation into a rotating firing squad, with each row of soldiers firing a shot then going to the rear of the formation to reload. Inspired by reading Aelian's descriptions of the use of ranks and counter-marching by the soldiers of Imperial Rome in the context of the Roman gladius pilum and sword spear, William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg in the 'decisive leap' realized that the same technique could work on men with firearms. In a letter to his cousin Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange in December 8, 1594 he said:

: “I have discovered the evolutionibus method of getting musketeers and others with weapons not only to practice firing, but to continue to do so in a very effective battle formation (that is, they do not fire single fire or from behind a barrier....). Immediately, as soon as the first discharge is fired, then by training, they will go to the back. The second rank, either going forward or stopping, will then shoot exactly the same as the first. After this, the third and after the discharges will do the same. When the last digit fires, the first one will reset as the following diagram shows:.

Once volley firing was developed, the rate of fire and effectiveness were greatly increased, and the arquebus moved from being a support weapon to the primary focus of the earliest modern armies.

Triumphant procession across Europe and beyond

Major battles of the early 16th century clearly demonstrated the strength and power of handguns. The famous American historian Gilmartin believes that at this time the arquebus was already “known throughout Europe.” The same can be said about muskets. An eyewitness to the famous Battle of Pavia, Francesco da Carpi, who observed the work of the Spanish arquebusiers, said about the new weapon: Nomen certe novum (“truly a new name”). And he was absolutely right.

Arquebuses were inferior to bows and crossbows in almost all characteristics: rate of fire, accuracy, penetrating ability. However, handling a bow required great skill, which was achieved through many years of training. The arquebusier could be prepared relatively quickly.

Already in 1527, the French king Francis ordered that the troops have harquebusiers (hacquebuttiers) and arquebusiers (harquebusiers). Even earlier, in 1518, the Venetian Council of Ten decided to replace crossbows with arquebuses in the armament of the war galleys of the republic.

In the 16th century, the name “arquebus” was included in almost all European languages. By the way, the word “musket” was not so popular. Heavy guns continue to be called gakovnitsa.

In 1543, the new arquebus weapon was brought by the Portuguese to Japan, where it quickly became popular. Serial production of arquebuses was launched in the province of Satsuma. In 1575, new weapons played a decisive role in the Battle of Nagashino.

In Japan, the advent of firearms led to the same consequences as in Europe. Heavy armor is a thing of the past; the huge two-handed tachi swords have been replaced by elegant katanas.

Official creator of gunpowder

Although this mixture was invented a long time ago, its official creator was Konstantin Anklitzen, better known as Berthold Schwartz. The first name was given to him at birth, and he began to be called Bertold when he became a monk. Schwarz means Black in German. This nickname was given to the monk because of an unsuccessful chemical experiment, during which his face was burned black.

In 1320, Berthold officially documented the composition of gunpowder. His treatise “On the Benefits of Gunpowder” described tips on mixing gunpowder and operating it. In the second half of the 14th century, his recordings were appreciated and used to teach military skills throughout Europe.

In 1340, a factory for the production of gunpowder was built for the first time. This happened in the east of France, in the city of Strasbourg. Soon after the opening of this enterprise, a similar one was opened in Russia. In 1400, there was an explosion at the factory, which caused a big fire in Moscow.