| SMS Friedrich Karl | ||

| SMS Friedrich Karl | ||

| Banderas | ||

| Write down | ||

| Shipyard | News Company of forges and shipyards La Seyne , Tolon | |

| Class | unique | |

| Type | armored side drum | |

| Operator | Imperial German Navy | |

| Authorized | 1865 | |

| Initiated | 1866 | |

| Reset | January 1867 | |

| Nominated | October 1867 | |

| Bach | June 1905 | |

| Appointments | scrapped 1906 | |

| General characteristics | ||

| bias | 6932 | |

| Length | 94,14 | |

| Manga | 16.6 m | |

| Draft | 6.9 m | |

| drilling rig | Bergantine • 2100 m² | |

| Armor | • Belt: 127 mm • Command tower: 114 mm | |

| Armament | • 2 guns 210 mm L/22 • 14 guns 210 mm L/19 | |

| Movement | • 1 steam engine • 6 boilers • 1 propeller | |

| Force | 3550 hp | |

| Speed | 13.5 knots | |

| Autonomy | 2210 on 10 nuds | |

| Crew | • 33 officers • 498 crew members | |

| Capacity | 624 tons of coal | |

| [edit data in Wikidata] | ||

SMS Friedrich Carl

[Note 1] was an ironclad warship built for the Prussian Navy in the mid-1860s and from 1871 part of the Imperial German Navy.

The ship was built at the Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers

in Toulon;

her keel was laid in 1866 and launched in 1867. The ship was handed over to the Prussian fleet in January 1867. She was the third ironclad ordered by Prussia after SMS Arminius and SMS Prinz Adalbert. , although she was acquired fourth, as SMS Kronprinz, which was ordered later, entered service before Friedrich Karl

.

« Friedrich Karl

" served in the Navy from her appointment in 1867 until 1895, when she was removed from the front lines to serve as a training ship.

During the Franco-Prussian War, between 1870 and 1871, the ship was part of the main German squadron under the command of Vice Admiral Jachmann. However, problems with her machinery were constant on both the Friedrich Karl

and the other two ships of the squadron, so she made only two exits from the port of Wilhelmshaven to challenge the French blockade, without either of these two exits causing a confrontation between both fleets happened.

« Friedrich Karl

" was also deployed in Spain during the Cantonal Revolution of 1873, during which he helped capture three cantonal ships in two acts. The ship was modernized at the Imperial Dockyards in Wilhelmshaven in the 1880s.

In 1902 it was renamed SMS Neptune

"and was used in the port until June 1905, when it was deregistered from the naval register. The following year it was sold to a Dutch scrapyard for dismantling.

Design

General characteristics

« Friedrich Karl

"had a waterline length of 91.13 m and a maximum length of 94.14 m. Its width was 16.6 m, draft - 6.9 m at the bow and 8.05 m at the stern. The ship was designed to displace 5971 tons with normal load and 6932 tons with combat load. The ship's hull was built with a transverse iron structure that divided it into eight watertight compartments, and had a double bottom covering 76% of its length. [ 1 ]

« Friedrich Karl"

showed excellent seaworthiness;

it responded to rudder commands and had a moderate turning radius. However, it was a bit unbalanced and you had to keep the rudder 6 degrees to the left to keep it heading straight. The ship's crew consisted of 33 officers and 498 men, including non-commissioned officers and sailors, and while she served as flagship, the crew was increased by 6 officers and 35 men, including non-commissioned officers and sailors. The Friedrich Karl

carried several smaller vessels of different classes, including a large barge, two speedboats, a pinnace, two cutters, a dvajolas and a dinghy. [ 1 ]

Power was provided by a simple expansion two-cylinder horizontal steam engine, which was supplied with steam from a total of 6 boilers, divided into two rooms with 11 fireplaces, which supplied the machine with steam at 2 atmospheres, providing a total of one power of 300 hp. on a single propeller with four blades and a diameter of 6 m. All this equipment allowed it to reach a speed of 13 knots, reaching 3550 hp during sea trials. and 13.5 knots. The ship carried 624 tons of coal, giving it a range of 2,210 nautical miles at a cruising speed of 10 knots. The 2010 m² drilling rig complemented the steam engine, slightly increasing its autonomy. The steering was controlled by a single rudder. [ 1 ]

Armament and armor

Originally " Friedrich Karl

"was equipped with 26 72-pound rifled guns. After delivery to Prussia, these guns were replaced by two 210 mm L/22 guns and fourteen 210 mm L/19 guns. [Note 2]L/22s had a vertical firing angle of -5 degrees to a maximum elevation angle of 13 degrees, giving them a maximum range of 5,900 meters. L/19 had a vertical firing angle of -8 to 14.5 degrees, but the lower muzzle velocity due to the shorter barrel length reduced the firing range to 5200 m. The two types of guns fired the same type of projectiles, for which they had only 1656 shells on board. Fourteen L/19 guns were placed in the central battery amidships, seven per side. L/22s were located at the ends of the ship. [ 2 ] Six revolving guns and five 350 mm torpedo tubes were later added. [3] Two devices were placed in the bow, one on each side and the last one at the stern, all of them above water and with a total supply of 12 torpedoes. [2]

Armor of Frederick Charles

consisted of iron plates on teak plates. The waterline belt was 114mm thick iron over 254mm teak. The central battery was protected by 114 mm of iron by 260 mm of teak wood. The battery cover was protected by 9mm thick iron plates. The command post had 114 mm iron armor on a 400 mm teak covering. [ 1 ]

Seven Persons of Saint Louis

The ship was largely outdated even before it was commissioned, which predetermined its fate in the US Navy. During its twenty-four years of service, it was used in seven guises: for about a year - as an armored cruiser, for ten years it was in reserve and under repair, and the rest of the time it served as a representative, training and patrol ship, stationary and even armored transport.

During the closed beta testing of the World of Warships game, the armored cruiser St. Louis gained enormous popularity among players and is rightfully valued by them as a powerful (at its level) artillery platform.

Military historians' assessments of the real-life ship, which was part of the US Navy from 1906 to 1930, are not so high. Thus, Yu. Yu. Nenakhov evaluates ships of this type as follows: “... they had insufficient speed, weak weapons for their class and were ineffective as armored cruisers

.

In this article we will try to get an objective picture of the strengths and weaknesses of the armored cruiser St. Louis. Cruiser "St. Louis". Date and place of photo unknown Source: navsource.org

Armored cruisers at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries

Armored cruisers owe their appearance to the French Navy. French admirals, realizing that they were unable to achieve parity with Great Britain in terms of the number of battleships, in the 1880s developed the military doctrine of “indirect action,” which provided for the widespread use of cruisers on the enemy’s long sea lanes, which was supposed to undermine, and if successful, undermine British rule at sea. French naval doctrine considered the armored cruiser as a universal ship, occupying an intermediate position between an ironclad and an armored cruiser, capable of carrying out raiding operations on commercial shipping routes, supporting the main forces of the fleet in a battle with the enemy's battle fleet, and also protecting its own shipping from the actions of enemy armored cruisers . This approach imposed very strict requirements on the armored cruiser:

- The cruising range was at least 10,000 miles, which required a supply of coal of at least 2,000 tons;

- Travel speed sufficient to pursue or break away from enemy armored cruisers;

- Armament and armor sufficient to combat enemy cruiser formations, including armored cruisers.

It soon became clear that the construction of a large fleet of universal armored cruisers was impossible for economic reasons, so by the 1890s, two main types of armored cruisers had emerged. Type "A" (also known as the "large armored cruiser" and "armored cruiser of the 1st rank") was a ship with a displacement of 11,000–15,000 tons and a cruising range of more than 10,000 miles, designed to wage raider warfare on enemy communications . Type "B" (also known as "small armored cruiser", "armored cruiser of the 2nd rank" and "counter-raider") was a ship with a displacement of 7,000–10,000 tons and a cruising range of about 5,000 miles, designed for reconnaissance and support the main forces of the fleet, as well as the fight against enemy raiders.

Performance characteristics

The ship, named after the American city of St. Louis (translated from French as “Saint Louis”), founded by French colonists, became the third cruiser of the same type. In Russian-language literature, this type of cruiser is also known as the Charleston type, after the name of the lead ship of the project. A total of three ships were built under this project for the US Navy.

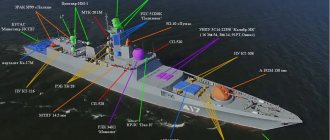

Diagram of the cruiser "St. Louis" as of 1908 Source: forum.worldofwarships.ru

Armored cruisers of the "St. Louis" class

| Ship | Shipyard | Bookmark date | Launch date | Commissioning date |

| "Charleston" | Naval Shipyard (Newport News) | 30.01.1902 | 23.01.1904 | 17.10.1905 |

| "Milwaukee" | Union Iron Works (San Francisco) | 30.07.1902 | 10.09.1904 | 11.05.1906 |

| "St. Louis" | Neafie and Levy Ship and Engine Building Co. (Philadelphia) | 31.07.1902 | 6.05.1905 | 18.08.1906 |

Structurally, "St. Louis" was an armored cruiser of the "B" type with a casemate placement of medium-caliber onboard artillery.

Basic geometric dimensions of the armored cruiser "St. Louis"

| Total displacement, t | 10839 |

| Length, m | 129,91 |

| Width, m | 20,12 |

| Draft, m | 6,86 |

Power plant

The cruiser St. Louis received a power plant consisting of vertical triple expansion steam engines and coal-fired steam boilers. Since strong draft was required for normal combustion of coal in the boiler furnaces, the cruiser was equipped with four high chimneys. A significant part of military historians are skeptical about the St. Louis's power plant, considering it to not provide the required speed, but at the beginning of the twentieth century, such power units were standard for armored cruisers.

The cruiser "St. Louis" is parked.

Philadelphia, 1906. Smoke coming from one chimney is the result of “idle” operation to provide energy to internal systems Source: navsource.org Power plants of armored cruisers of the early twentieth century

| Cruiser type | «St. Louis» | «Kent» | «County» | «Friedrich Karl» | "Izumo" |

| A country | USA | Great Britain | Great Britain | Germany | Japan |

| Year of laying of the lead ship | 1902 | 1899 | 1902 | 1900 | 1898 |

| Displacement, tons | 10 839 | 9956 | 10 850–11 024 | 9875 | 10 305 |

| Number of shafts | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Composition of the power plant | 2 triple expansion steam engines and 16 Babcock-Wilcox boilers | 2 triple expansion steam engines and 31 Belleville or Babcock boilers | 2 triple expansion steam engines and 22–23 Yarrow or Babcock boilers | 3 triple expansion steam engines and 14 boilers | 2 triple expansion steam engines and 24 Belleville boilers |

| Power, installations, hp | 21 000 | 22 189 | 21 508 | 18 540 | 14 500 |

| Fuel type | Coal | Coal | Coal | Coal | Coal |

| Fuel reserve, tons | 1650 | 1600 | 1950 | 1630 | 1402 |

| Maximum speed, knots | 22 | 22,4–23,5 | 22–23 | 20,5 | 21 |

Some authors criticize the St. Louis designers for using outdated steam engines and coal boilers instead of promising steam turbines and oil boilers, but the use of steam engines and coal was quite justified for the following reasons:

- Since it was assumed that the armored cruiser would operate most of the time outside the main fleet bases, it was equipped with steam engines, which, unlike steam turbines, did not require highly qualified labor for their repair;

- The actions of armored cruisers away from the main bases also implied the use of widely available coal (including its low-quality varieties) instead of very rare oil;

- The use of steam turbines, while creating problems with repairs and material supplies, did not, in fact, provide a fundamental improvement in the ship's performance.

Steam engines of the same type cruiser "Milwaukee" before installation. Union Iron Works shipyard, San Francisco, 1904 Source: navsource.org

The validity of the last statement is well illustrated by the characteristics of the Italian armored cruisers of the San Giorgio class.

Characteristics of Italian armored cruisers of the San Giorgio class

| Cruiser | "San Giorgio" | "San Marco" |

| Year of laying | 1905 | 1907 |

| Displacement, tons | 11 850 | 12 300 |

| Number of shafts | 2 | 4 |

| Composition of the power plant | 2 triple expansion steam engines and 14 Blachynden boilers | 4 Parsons steam turbines and 14 Babcock-Wilcox boilers |

| Power, installations, hp | 19 595 | 23 030 |

| Fuel type | Coal | Coal |

| Fuel reserve, tons | 1500 | 1500 |

| Maximum speed, knots | 22 | 23,75 |

| Cruising range, miles at a speed of 10 knots | 6270 | 4800 |

The four-shaft "San Marco" equipped with turbines, having a speed of 1.75 knots greater than the two-shaft "San Giorgio" equipped with steam engines (an advantage of about 10%), was inferior to it in cruising range by 1,400 miles (about 20%).

And was the speed of the armored cruiser St. Louis really that low?

Formally, the American cruiser was inferior in speed to German armored cruisers, created taking into account the requirements for performance characteristics that increased after the Russo-Japanese War. Speed characteristics of German armored cruisers

| Cruiser type | Year of laying of the lead ship | Number of ships built | Maximum speed, knots |

| "Bremen" | 1902 | 7 | 23,1 |

| "Konigsberg" | 1905 | 4 | 23–24,1 |

| "Dresden" | 1906 | 2 | 24–25,2 |

| "Mainz" | 1907 | 4 | 25,5–26,7 |

On the other hand, the German cruisers, which had been on a cruise for a long time and used low-quality coal, could not reach the declared maximum speed, which was confirmed by the death of the armored cruisers Leipzig and Nuremberg during the Battle of Falklands in 1914 from the fire of rather slow-moving English armored cruisers .

Comparative speed characteristics of German and English cruisers participating in the Battle of Falklands

| German cruiser | Maximum speed according to official technical specifications, knots | Actual speed shown during the battle, knots | English cruiser | Maximum speed according to official technical specifications, knots |

| Leipzig | 23,1 | 22 | "Cornwall" | 22,4–23,5 |

| "Nuremberg" | 23–24,1 | 19 | "Kent" | 22,4–23,5 |

Thus, taking into account the realities of the First World War, the cruiser St. Louis, of course, not being a “sprinter”, in terms of speed characteristics, generally corresponded to the responsibilities assigned to it.

Booking

The armor of armored cruisers consisted of horizontal (armored deck) and vertical (main armor belt covering the side above the waterline, armor of artillery towers, casemates and conning tower). An additional element of vertical protection was the side coal bunkers - full bunkers above the waterline and behind the side armor created an additional barrier for fragments, and also reduced the damaging effect by absorbing the explosion energy. The underwater protection of armored cruisers of the early twentieth century was completely ineffective for an understandable reason - at that time there was a significant underestimation of the potential threat from torpedo and mine weapons. In essence, almost the only underwater protection was coal bunkers under the waterline, which could to some extent reduce the risk of flooding as a result of a torpedo strike.

Cruiser St. Louis, 1906–07 Source: navsource.org

The armor of the cruiser St. Louis, which consisted of an onboard armor belt and an armored deck that protected only the vehicles and boilers (thickness above the power plant - 51 mm, at the ends and on the slopes - up to 76 mm), has been criticized by many experts.

However, we should not forget that such reservations were typical for all cruisers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Thickness of armor of armored cruisers of the early twentieth century, mm

| Cruiser type | «St. Louis» | «Kent» | «County» | «Friedrich Karl» | «Izumo» |

| Belt | 102 | 51–102 | 51–152 | 75–100 | 89–178 |

| Deck | 51–76 | 20–51 | 20–51 | 50–80 | 63 |

| Casemates | 102 | 51–102 | 51–152 | 100 | 152 |

| Towers | – | 127 | 127 | 150 | 152 |

| Chopping | 127 | 254 | 305 | 150 | 76–356 |

Such armor was very effective in countering armored and small armored cruisers armed with 105–152 mm caliber guns. Thus, during the already mentioned Battle of Falklands on December 8, 1914, the gunners of the cruiser Nuremberg scored thirty-eight hits with 105-mm shells on the English armored cruiser Kent, which led to... the death of four and the injury of twelve people. But the ability of the armor of the cruiser St. Louis to withstand guns with a caliber of over 152 mm, which were in service with a significant part of the armored cruisers, seems very doubtful. To be fair, it should be noted that combat against such ships was planned only with an overwhelming fire advantage, which significantly shortened the battle time and minimized the likelihood of receiving heavy damage. In general, the St. Louis's armor met the tasks assigned to the B-type cruisers to a limited extent.

Armament

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, there were two doctrines for arming armored cruisers in the world. One theory, which viewed the armored cruiser as a smaller battleship, included a small number of main-caliber guns in individual or twin rotating turrets at the bow and stern, as well as a significant number of medium-caliber guns in casemates (both on the battery deck and in the superstructures). on the main deck). The second theory, which considered the armored cruiser as an enlarged version of the armored cruiser, provided for the replacement of main caliber guns with medium caliber guns. The British, who laid down a series of ten Kent-class armored cruisers in 1899–1901, were big fans of abandoning main-caliber guns, which had a strong influence on the design of the armament of the cruiser St. Louis. It is interesting that by the time the American cruisers were laid down, the British themselves had significantly cooled down to the idea of abandoning main-caliber artillery - on the County-class cruisers laid down in 1902 (a development of the Kent class), it was decided to replace the armament of fourteen 152-mm guns with four 190 -mm (in the bow and stern turrets) and six 152-mm guns (in casemates).

Cruiser "St. Louis" in San Francisco Bay Source: navsource.org

Armament of armored cruisers of the early twentieth century

| Cruiser type | «St. Louis» | «Kent» | «County» | «Friedrich Karl» | «Izumo» |

| Artillery weapons | |||||

| 203–210 mm guns | – | – | – | 4 | 4 |

| 190 mm guns | – | – | 4 | – | – |

| 150–152 mm guns | 14 | 14 | 6 | 10 | 14 |

| 88 mm guns | – | – | – | 12 | – |

| 76 mm guns | 18 | 10 | 2 | – | 12 |

| 47 mm guns | 12 | 3 | 18 | – | 8 |

| 37 mm guns | 8 | – | – | – | – |

| Torpedo tubes | |||||

| 450–457 mm | – | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

The main striking force of the cruiser St. Louis was fourteen 152-mm Mark 6 guns with a barrel length of 50 calibers (projectile weight - 45.4 kg, rate of fire - 4 rounds per minute. Data on the rate of fire of 6 rounds per minute probably refer to to Mark 8 guns installed on the same type cruiser "Milwaukee"), firing range - up to 13,720 meters at an elevation angle of +15°). Mine artillery consisted of eighteen 76-mm guns (rate of fire - up to 15 rounds per minute), as well as twelve 47-mm and eight 37-mm guns. Unlike many of her “contemporaries,” the cruiser St. Louis did not have torpedo tubes.

76-mm guns on the left side. The upper deck of the same type cruiser Milwaukee. Mare Island Navy Yard (California), April 27, 1916 Source: navsource.org

Features of the use of artillery weapons of armored cruisers

Supporters of arming armored cruisers with only medium-caliber guns believed that:

- The presence of guns of the same caliber will simplify adjustments, which will reduce the time from the moment of opening fire to covering the target and increase the number of hits;

- The rate of fire of 152 mm guns will be significantly higher than that of 190–210 mm guns.

Practice has refuted both of these assumptions. Firstly, adjusting the fire of 152-mm guns installed on the deck and in casemates turned out to be just as difficult as adjusting the fire of guns of various calibers. In this case, it would not be amiss to provide the opinion of a competent participant in the events. The flagship artilleryman of the brigade of cruisers of the Russian Black Sea Fleet (the brigade included Bogatyr-class cruisers, which had a mixed arrangement of 152-mm guns in turrets and casemates), senior lieutenant A. G. Magnus in his report dated May 1916 about (due to different rate of fire due to differences in the aiming methods themselves, as well as differences in adjustments when controlling fire due to the use of different types of sights - author's note). Alternating targeted salvoes from turret guns with salvoes from deck guns turned out to be practically impossible: the turrets required test salvoes, and, in addition, they needed a special spotter. Secondly, the use of an electric drive, mechanical feed and other technical innovations made the rate of fire of 152 mm and 190–210 mm guns almost the same. In conditions where the number of shells hitting the target was comparable, ships that had shells with a greater destructive effect received an absolute advantage.

The standard use of artillery weapons by armored cruisers of the B type, designed to combat enemy armored cruisers, was reduced to two successive phases: the pursuit phase and the destruction phase.

Pursuit phase

While pursuing an enemy armored cruiser, the armored cruiser fired from its bow guns in order to immobilize the enemy ship or slow down its speed of movement.

This phase of the battle was characterized by an extremely small number of hits (about 1%). At the beginning of the 20th century, fire adjustments were made in bursts and required a salvo of at least four guns, which precluded the use of adjustments in conditions when only one or two bow guns were firing, and made possible target destruction almost accidental. The potential capabilities of armored cruisers of the early 20th century when firing from bow guns were as follows (the estimated battle time is 60 minutes): Potential capabilities of armored cruisers of the early 20th century when firing from bow guns

| Cruiser type | Number of guns | Caliber, mm | Practical rate of fire, rounds per minute | Number of hits | Projectile weight, kg | Total mass of hit shells, kg |

| "St. Louis" | 1 | 152 | 4 | 2 | 45,4 | 91 |

| "Kent" | 2 | 152 | 4 | 5 | 45,4 | 227 |

| "County" | 2 | 190 | 3 | 4 | 91 | 364 |

| "Friedrich Karl" | 2 | 210 | 3 | 4 | 90 | 360 |

| "Izumo" | 2 | 203 | 3 | 4 | 90 | 360 |

In conditions where only a single, almost accidental hit was possible, the incomparably higher firing range and destructive capabilities of 190–210 mm shells were decisive for the outcome of the battle (even a single shell could destroy the engine room). A case in point is the battle on April 14, 1916 between Russian and Turkish cruisers. During the seven-hour pursuit, the Russian armored cruiser Cahul, which sailed at almost 22 knots for about two hours, and at a speed of 20.6 to 21 knots for the remaining 5 hours, was never able to approach the Turkish cruiser Gemediye. , allowing artillery fire. In the report on the results of the battle, the commander of the Cahul, captain 1st rank S.S. Pogulyaev, indicated that “for the results of the chase to be valid, it is necessary to have at least two 203-mm guns on the ship.”

Destruction phase

In a battle of destruction, the opposing ships exchanged broadsides. Since adjustments were allowed with this method of firing, the number of hits increased significantly and fluctuated between 3–5%.

The potential capabilities of armored cruisers of the early 20th century when conducting onboard fire were as follows (the estimated battle time is 10 minutes, hits are 5% of the total number of shells fired):

Potential capabilities of armored cruisers of the early 20th century when conducting onboard fire

| Cruiser type | Number of guns | K caliber, mm | Practical rate of fire, rounds per minute | Number of hits | Projectile mass , kg | Total mass of hit shells, kg |

| Cruisers without main battery guns | ||||||

| "St. Louis" | 7 | 152 | 4 | 14 | 45,4 | 636 |

| "Kent" | 9 | 152 | 4 | 18 | 45,4 | 817 |

| Cruisers with main caliber guns | ||||||

| "County" | 4 | 190 | 3 | 6 | 91 | 546 |

| 3 | 152 | 4 | 6 | 45,4 | 272 | |

| Total for cruiser | 7 | 12 | 818 | |||

| "Friedrich Karl" | 4 | 210 | 3 | 6 | 90 | 540 |

| 5 | 150 | 4 | 10 | 45 | 450 | |

| Total for cruiser | 9 | 16 | 990 | |||

| "Izumo" | 4 | 203 | 3 | 6 | 90 | 540 |

| 7 | 152 | 4 | 14 | 45 | 630 | |

| Total for cruiser | 11 | 20 | 1170 |

The mass of the broadside of armored cruisers armed with main and medium or only medium caliber guns was quite comparable. However, “St. Louis” was significantly inferior to its “contemporaries” in terms of the mass of the broadside due to the extremely poor placement of medium-caliber guns:

- Unlike the “contemporaries,” who used two-gun turret artillery mounts as bow mounts, the cruiser “St. Louis” was equipped with individual open mounts that were significantly inferior in protection and fire density;

- Four cannons were on the upper deck. Based on the operating experience of other similar ships, it is known that such guns could not be used in high seas due to low firing accuracy. There is no exact data on the use of these guns on the St. Louis, but the fact that two stern 152-mm guns were dismantled no later than 1908 indirectly confirms their low effectiveness;

- Eight cannons were on the main deck. Along with high security, these guns had a very narrow field of fire, especially towards the bow and stern of the cruiser.

Already in 1905, it became clear that the anti-mine artillery installed on the cruiser was absolutely ineffective when used for its intended purpose (to destroy enemy destroyers). However, the Americans were in no hurry to rearm, dismantling fourteen of the eighteen 76-mm guns only on the eve of the First World War. Probably, the American sailors did not see much prospects in using the St. Louis as an armored cruiser, since, having dismantled two 152-mm and fourteen 76-mm guns, they used the freed-up premises not to install new weapons, but to accommodate landing forces (up to 1740 people with weapons). During the First World War, the cruiser received two 76-mm anti-aircraft guns as air defense weapons.

In general, the St. Louis had driving characteristics and armor quite comparable to its contemporaries, but very weak artillery. The armament of this ship was so inconsistent with the generally accepted idea of the artillery of an armored cruiser that in a significant part of the sources it is classified as an “armored cruiser” or “light smooth-deck cruiser.”

Combat service "St. Louis"

Due to rapid technical progress and errors in the choice of weapons, the cruiser St. Louis was largely outdated even before commissioning, which predetermined its fate in the US Navy. During its twenty-four years of service, the ship was used in seven guises: for about a year - as an armored cruiser, for ten years it was in reserve and under repair, and the rest of the time it served as a representative, training and patrol ship, stationary and even armored transport. The service of the "St. Louis" began with the passage of Port Castries - San Diego from May 15 to August 31, 1907, during which he visited the cities of Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Punta Arenas, Valparaiso , Callao and Acapulco. In the spring and June 1908, the ship patrolled the west coast of the United States between Puget Sound and Honolulu, a task of armored rather than armored cruisers, and then (from July to October of that year) the coastal waters of Central America. Already on November 15, 1909, she was first put into reserve (being in reserve was short-lived, lasting until May 3, 1910), and after reactivation on July 13, 1910, she left Puget Sound and moved to San Francisco to undergo repairs (completed on October 7 1911).

Cruiser St. Louis, San Francisco, 1909–16 Source: navsource.org

Over the next few years, the St. Louis served as a training ship, performed representative functions, and was finally converted into a stationary ship (a ship performing garrison duty in a port - something between a floating battery, a control post, and a barracks). The cruiser was occasionally used to patrol the west coast of the United States and the eastern Pacific Ocean, including the Pearl Harbor area. On April 27, 1914, the St. Louis was withdrawn from the active fleet and arrived in San Francisco, where it served as a representative ship. The next return of the cruiser to the active fleet on July 10, 1916 was associated with emerging plans for the United States to enter the First World War. Although the use of the St. Louis can only be called conditional service as part of the active fleet. From July 29, 1916, the cruiser, arriving at Pearl Harbor, combined the functions of a stationary and tender (floating warehouse) for submarines of the 3rd Submarine Flotilla of the Pacific Fleet. It is interesting that with a regular crew size of 673 people in peacetime and 767 people in wartime, there were only 306 officers and sailors on board the ship (that is, less than 50% of the regular peacetime crew size).

The cruiser St. Louis in the Panama Canal, 1916 Source: navsource.org

After the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the St. Louis was returned to the Atlantic Fleet, where it served as a transport and escorted troop convoys to the shores of Europe. On April 20, the number of its crew was increased to 823 people due to 517 naval volunteers (reservists) and cadets, which once again emphasizes the attitude of the command to the combat capabilities of this ship. In total, the St. Louis made six crossings across the ocean (and after the first she was forced to undergo repairs), guarding convoys and delivering troops from New York to the ports of Great Britain and France. On average, the cruiser had six companies of infantry on board (about 1,500 people). One can imagine how great the losses among passengers would be if the cruiser were to engage in battle with the enemy.

The cruiser USS St. Louis leaves the Boston Navy Yard after repairs, September 14, 1917 Source: navsource.org

After the end of the war, from December 17, 1918 to July 17, 1919, the ship made seven more voyages, transporting American soldiers from Brest (France) to Hoboken (New Jersey, USA). A total of 8,437 military personnel were transported.

The cruiser St. Louis in camouflage, September 1918 Source: navsource.org

On July 29, 1920, the cruiser St. Louis and six destroyers were included in the US European squadron sent to Turkish Istanbul to protect American citizens, and on November 13–16 of the same year the ship made the transition from Constantinople to Crimea and back, delivering to Turkey refugees from Russia.

The cruiser St. Louis in port, September 1919 Source: navsource.org

After a one-year stay with the squadron, on November 11, 1921, the cruiser returned to Philadelphia, where she was decommissioned, underwent conservation repairs, and was put into reserve on March 3, 1922. On March 20, 1930, she was finally removed from the lists of US Navy ships, and on August 13, she was sold for scrapping in accordance with the provisions of the London Agreement on the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armaments.

Returning to the question asked at the beginning of the article, it should be recognized that in reality the cruiser St. Louis was not an “ideal combat platform” due to the erroneous rejection of main-caliber guns and errors in the placement of medium-caliber guns. However, we cannot completely agree with Yu. Yu. Nenakhov’s assessment of its complete unsuitability as an armored cruiser - the ship was, rather, “partially suitable.” "St. Louis", planned as a ship with "the armament and armor of a battleship and the speed of an armored cruiser",

hopelessly outdated while still on the slipway, turning rather into an armored cruiser with the speed of an armadillo. Any attempt to use the St. Louis as a classic armored cruiser, which promised a meeting with an enemy battleship or large armored cruiser, could be fatal for him. However, it could well be used to protect convoys from small enemy armored cruisers or in remote naval theaters like the Black Sea, where there were no enemy ships with large-caliber artillery.

Service history

In 1865, the Prussian navy ordered the armored ship Friedrich Carl

in French shipyards.

The following year she was laid down at the Societe Nouvelles des Forges et Chantiers La Seyne shipyard

in Toulon.

The ship was launched on January 16, 1867 and completed its work quickly at the end of that year. Friedrich Karl

was delivered to Prussia in October 1867 and handed over to the fleet on the 3rd of the same month. [ 1 ]

Franco-Prussian War

At the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the great numerical superiority of the Prussian fleet forced it to take a defensive position against the blockade imposed by the French fleet. [ 4 ] Friedrich Karl

and the airborne battery ironclads SMS Kronprinz and SMS König Wilhelm, together with the small ironclad SMS Prinz Adalbert, crossed the English Channel before France declared war, sailing from Plymouth on 10 July with the intention of sailing to the Azores.

However, on the 13th they decided to return to port due to rising tensions between France and Prussia. The ships arrived in Wilhelmshaven on July 16. [5] France declared war on Prussia three days later, on July 19. [4] Friedrich Karl

,

the Crown Prince

and

König Wilhelm

were concentrated in the North Sea, in the port of Wilhelmshaven. [4] They were later joined by the turret ship SMS Arminius, which was stationed in Kiel. [6]

Despite France's great naval superiority, insufficient pre-war plans meant that an assault on Prussian naval installations was only possible with Danish assistance, although this did not happen. [4] Four ships under the command of Vice-Admiral Jachman made an offensive sortie in August 1870 off Dogger Bank, although they did not encounter the French fleet. And " Friedrich Karl

, and the other two

ironclad

broadside batteries suffered from chronic equipment problems, meaning that

Arminius

had to assume responsibility for naval operations from that point on.

[7]The ships " Friedrich Karl

", "

Kronprinz

" and "

König Wilhelm

" took refuge on the island of Wangerooge (East Friesland) for most of the conflict, while the "

Arminius

" stood at the mouth of the Elbe River.

[8] On 11 September the three battleships were ready for action and joined Arminius

for the purpose of developing a new operation in the North Sea. However, there was no confrontation, since by that time the French fleet had already taken refuge in their country. [7]

Deployment in Spain

Capture of the steam vigilante SMS by Fiedrich Kark

In early 1873, during the First Spanish Republic, the Cantonal Revolution occurred. « Friedrich Karl

"under the command of Vice Admiral Reinhold Werner, sailed into Spanish waters along with two other unarmored ships.

The ships joined the British squadron patrolling the southeast coast of Spain. The cantonal forces took control of four of the seven ironclads of the Spanish Armada, as well as several wooden-hulled frigates and warships. Admiral Werner, the group's senior officer, took command of the Anglo-German forces. [ 9 ]The detachment blocked two battleships in the port of Cartagena after they bombarded coastal cities. [10] On July 23, while sailing in Alicante, the Friedrich Karl

collided with the military steamer

Vigilante

with Antonio Galvez Arce on board and captured it, citing the central government's piracy decree of July 20.

canton flag. [ 11 ] The observer was sent

to Gibraltar and was returned to government forces after lengthy negotiations. [12] [] The Cantonalists considered declaring war on Germany after this takeover, but ultimately decided not to do so, [13] [] also because this takeover was carried out without the sanction of Berlin. [ 15 ]

Screw frigate Almansa and armored frigate Vitoria

set out from Cartagena "to a foreign power" (i.e. Almeria) to try to force them to join the Cantonalist cause or, failing that, to raise funds for Canton.

Cartagena. When the city refused to pay, it was bombed and taken by the cantonalists, who themselves collected tribute. They later sailed to Málaga to try to win the city over to the Cantonalist cause, but on 1 August 1873 the ironclad frigates SMS Friedrich Carl

and HMS Swiftsure, German and British respectively, under the joint command of Reinhold von Werner, captured the Cantonal ships by virtue of the Spanish government's decree of declaration naval forces of the canton by pirates, [11] [], but without obtaining permission from either London or Berlin.

[ 17 ] During the standoff, Anglo-German forces captured both ships almost without resistance, [ 18 ] later returning them again after difficult negotiations to government forces in Gibraltar. [11] Little resistance to capture was due to the fact that General Contreras, one of the leaders of the cantonalist forces, was on board the Almansa,

[ ] as it was a wooden frigate in front of two armored vehicles.

it also prompted the Vitoria

to surrender without resistance to avoid reprisals against the general and the Almansa's 400 crew. [ ]

After this last action " Friedrich Karl

returned to Germany, and Werner was relieved of command. [ 18 ] Chancellor Otto von Bismarck ordered a council of war against Admiral Werner, whose actions he considered excessive. Bismarck prohibited the Imperial German Navy from operating in the future under "gunboat diplomacy". [ 10 ]

During this deployment, Alfred von Tirpitz, Alfred von Tirpitz, was part of its crew as one of its officers, who would later become commander and architect of the Imperial Navy. [21]

Latest services

Friedrich Karl's torpedo nets were installed in 1885

, which she stored until 1897. During this period she was used as a training ship, training on her, among others, those who would become commanders of the High Seas Fleet of Franz von Hipper [22] and his predecessor and later commander of the Imperial Navy, Reinhard Scheer.

[23] She was disarmed in 1895 and continued to be used for torpedo testing from 11 August of that year until 21 January 1902, when she was renamed SMS Neptune

and used for various port services.

Her former name was used on the new armored cruiser, SMS Friedrich Karl, [1] launched 22 June 1902. [24] Neptune

was decommissioned 22 June 1905 and sold in March 1906 to a Dutch firm scrapped for 284,000 gold frames, after which it was towed to Holland and scrapped. [ 1 ]

References

- ↑ a b c d e f g

(Gröner, 1990, p. 2) - ↑ a b

(Gröner, 1990, pp. 2-3) - Gardiner, 1979, p. 243.

- ↑ a b c d

(Sondhaus, 1914, p. 101) - (Wilson, 1896, p. 273)

- (Wilson, 1896, p. 277)

- ↑ a b

(Sondhaus, 1914, p. 102) - (Wilson, 1896, p. 278)

- (Sondhaus, 1914, p. 121)

- ↑ a b

(Sondhaus, 1914, p. 122) - ↑ a b c d

Rolandi Sanchez-Solis, Manuel. "The First Republic. 3rd part: From counter-rebellion to the final liquidation of the Republic". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2011 - (Green, 1998, p. 279)

- Green, 1998, p. 280.

- (Perez Crespo, 1990, pp. 175-177)

- (Perez Crespo, 1990, p. 178)

- (Perez Crespo, 1990, pp. 162-164)

- (Perez Crespo, 1990, pp. 211-212)

- ↑ a b

(Perez Crespo, 1990, pp. 219-229) - (Perez Crespo, 1990, p. 217)

- (Perez Crespo, 1990, pp. 217-218)

- (Olivier, 2004, pp. 108-109 and 126)

- (Philbin, 1982, p. 4)

- Sweetman, 1997, p. 390.

- Groener, 1990, p. 51.

Bibliography

- Green, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of Ironclad Ships, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: United Publishing House. ISBN 0938289586. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2011

- Gardiner, Robert (1979). Conway's "The Fighting Ships of the World 1860–1905." . Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Groener, Erich (1990). German warships 1815–1945

. Volume. I: Large surface vessels. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6. - Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval War 1815-1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415214780.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Lowe, Marston and Company.

- Perez Crespo, Antonio (1990). Canton of Murcia. Murcia: Accademia Alfonso X el Sabio, DL, 1990. ISBN 0870219073.

- Philbin, Tobias R., III (1982). Admiral von Hipper: An Inconvenient Hero (BR Grüner Publishing Co.). Amsterdam. ISBN 9060322002.

- Sweetman, Jack (1997). Great Admirals: Command at Sea, 1587–1945 (Naval Institute Press). Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 9780870212291.

- Olivier, David H. (2004). German Naval Strategy, 1856-1888: Tirpitz's Predecessors. London. ISBN 0-7146-5553-8.

Footnotes [edit]

Notes[edit]

- "SMS" means " Seiner Majestät Schiff

" or "His Majesty's Ship".

Quotes [edit]

- Dodson, page 17.

- ↑

Dodson, pp. 17–18. - ^ B s d e e Groners, p. 2.

- ^ a b Groener, pp. 2–3.

- Gardiner, p. 243.

- Dodson, page 18.

- "Shipping Intelligence". Glasgow Herald

(9492). Glasgow. June 4, 1870 - ^ abcd Sondhaus, page 101.

- Wilson, p. 273.

- Wilson, p. 277.

- ^ ab Sondhaus, page 102.

- Wilson, p. 278.

- Dodson, page 25.

- Sondhaus, page 121.

- ^ ab Sondhaus, page 122.

- Green and Massignani, p. 279.

- Green and Massignani, p. 280.

- ↑

Dodson, pp. 25–27, 30. - Jump up

↑ Dodson, pp. 30, 32. - Groner, pp. 2, 51.